Dynamic Event-Triggered, Fixed-Time Control for Heterogeneous Multi-Agent Systems with Hybrid DoS Attacks

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Since DoS attacks disrupt the message communication between agents, a controller may not be able to receive system information and complete controller updates, even though the triggering condition has been met. To solve this problem, most of the existing control strategies assume that the real-time information of DoS attacks are known and have to stop triggering when the systems are under DoS attacks, which is difficult to achieve and makes the control scheme even more conservative.

- Compared to the static event-triggered control strategy, the core advantage of the dynamic event-triggered control strategy lies in reducing the controller update frequency by decreasing the conservatism of the triggering condition. The key to this strategy lies in the design of the dynamic event-triggering condition. Currently, the most fundamental method is to add a non-negative dynamic term that approaches zero over time with respect to the static event-triggered condition. However, when the problem shifts from asymptotic consensus to fixed-time consensus in multi-agent systems (MASs), this traditional design faces a serious challenge: the dynamic term must not only remain non-negative to preserve the advantage of reduced conservatism, but it must also ensure that the system achieves consensus within a fixed time. These dual requirements make the design of the dynamic term particularly challenging. Consequently, although the dynamic event-triggered control strategy offers advantages in terms of reduced conservatism, the dual constraints in designing the dynamic event-triggering condition for fixed-time consensus scenarios have led to its limited adoption in existing research on fixed-time consensus problems for MASs.

- Based on whether the DoS attacks are known or not, two different dynamic compensators and the corresponding consensus criteria are provided, which can achieve the fixed-time consensus between dynamic compensators and leader systems regardless of whether the attacks are known. Moreover, one additional consensus criterion based on a special case, which can reduce the conservatism of the given control schemes successfully, is also provided.

- A new type of dynamic term is designed in this paper. On this basis, the dynamic event-triggered condition is constructed and a novel dynamic event-triggered control scheme is proposed. This scheme not only ensures HMASs achieve quasi-consensus within fixed time, but it also has lower conservatism than a static event-triggered control scheme, thereby reducing the update frequency of the controller.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Notations

2.2. Topology Graph Knowledge of MASs

2.3. DoS Attacks

- : is a switching signal representing active DoS attacks mode at time instant t, with s being the total number of DoS attacks modes.

- represents the topology matrix without DoS attacks.

- () corresponds to the topology matrix under the w-th DoS attacks mode.

- if , ; otherwise, () means the same thing to as () to H.

- 1.

- for any

- 2.

- For any , if for some , there exists such that , and for .

3. Problem Formulation

4. Event-Based Control Scheme Under Known DoS Attacks

4.1. Design of Dynamic Compensator

4.2. Dynamic Event-Triggered Control Scheme

- By taking the derivative of , we have

5. Event-Based Control Scheme Under Unknown DoS Attacks

5.1. Design of Dynamic Compensator

5.2. Dynamic Event-Triggered Control Scheme

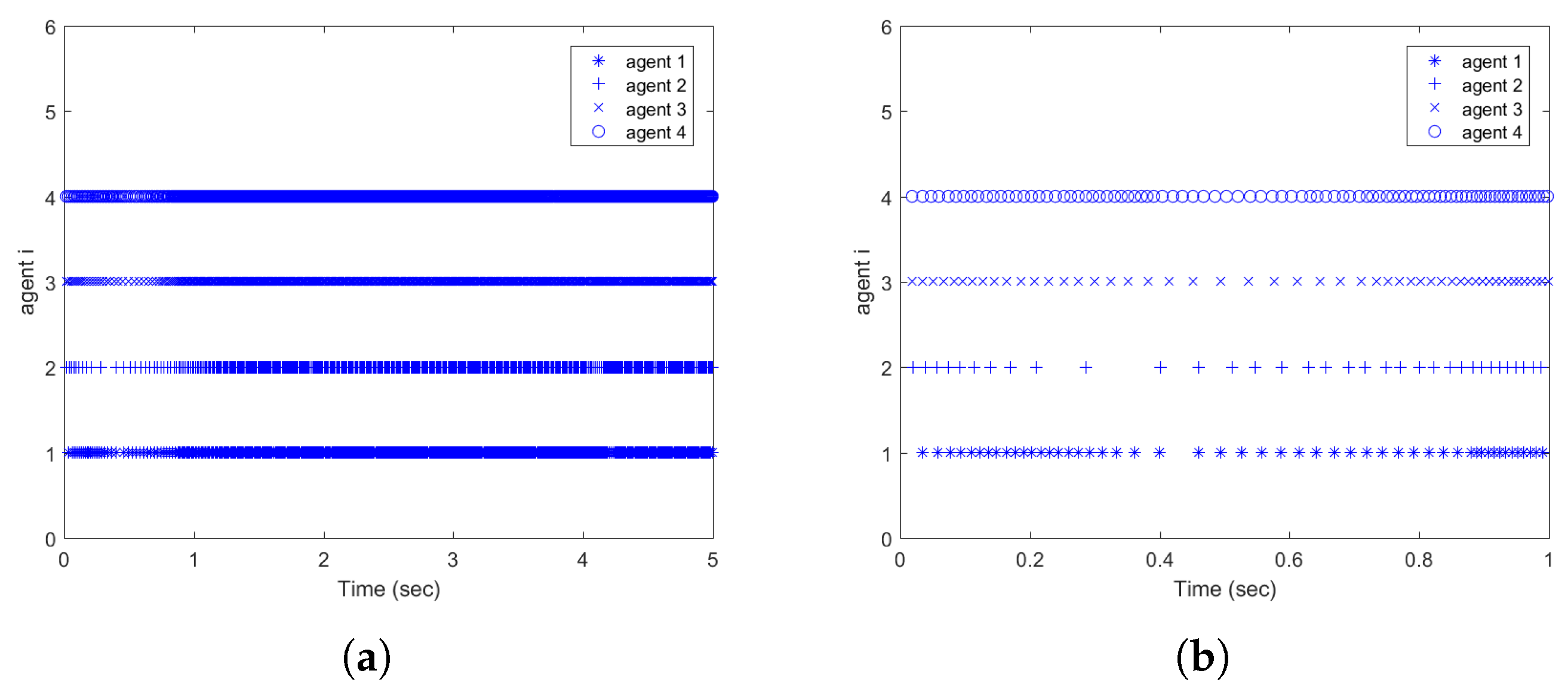

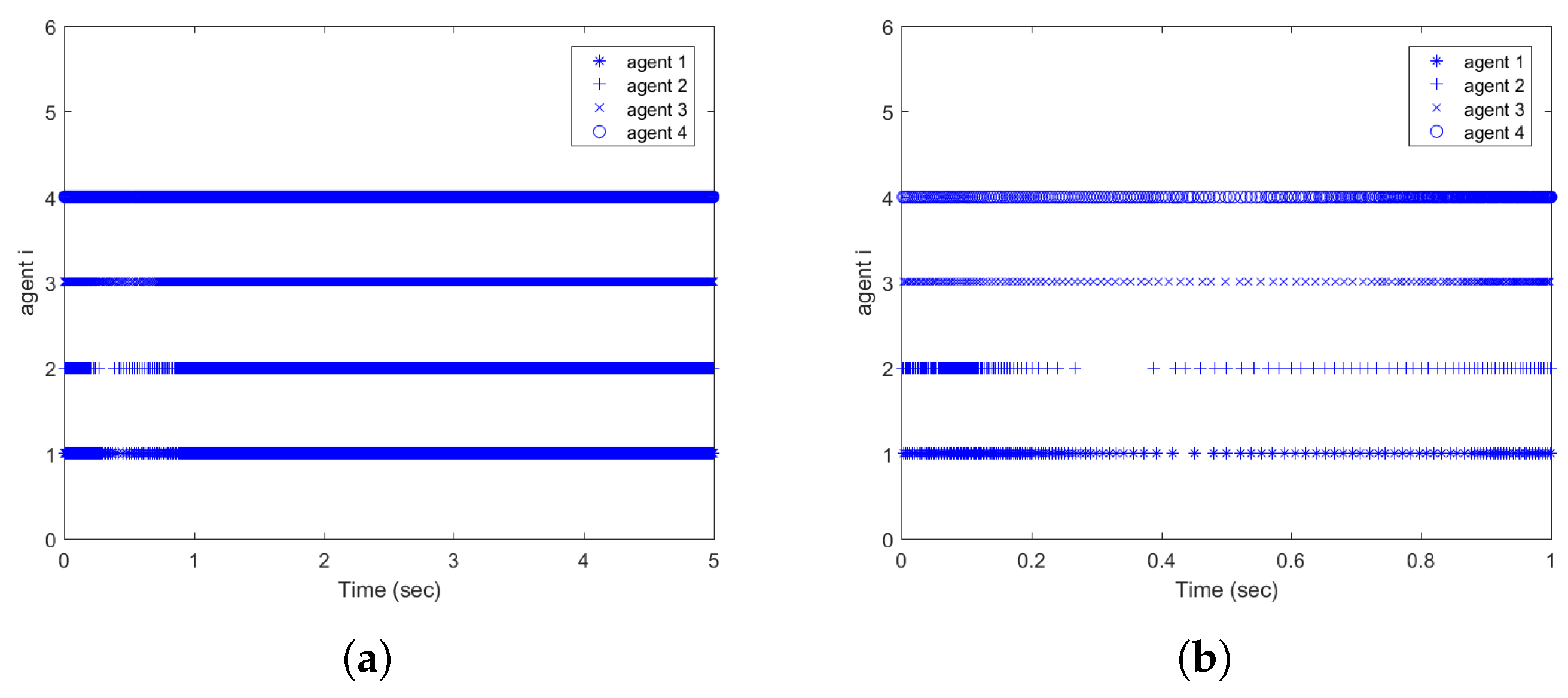

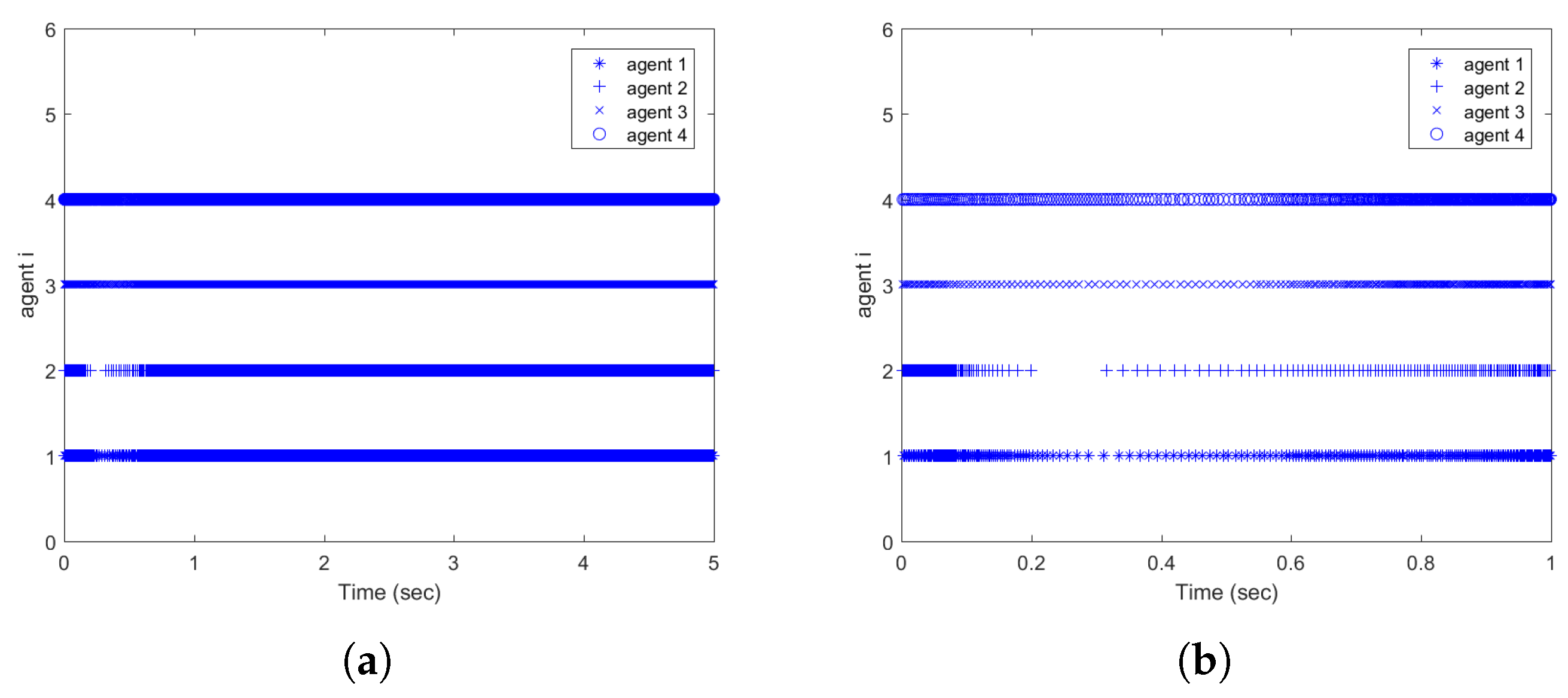

6. Numerical Example

7. Practical Significance and Challenges

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HMASs | Heterogeneous multi-agent systems |

| DoS | Denial-of-service |

| MASs | Multi-agent systems |

References

- Vidal, R.; Shakernia, O.; Sastry, S. Formation control of nonholonomic mobile robots omnidirectional visual servoing and motion segmentation. IEEE Int. Conf. Robot. Autom. 2003, 1, 584–589. [Google Scholar]

- Olfati-Saber, R.; Murray, R.M. Distibuted cooperative control of multiple vehicle formations using structural potential functions. In Proceedings of the 15th of IFAC World Congress, Barcelona, Spain, 21–26 July 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton, J.R.; Bread, R.W. Synchronized multiple spacecraft rotations. Automatica 2002, 38, 1359–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fax, J.A.; Murray, R.M. Information flow and cooperative control of vehicle formations. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2004, 49, 1465–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Han, J.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, H. H∞ consensus for linear heterogeneous discrete-time multiagent systems with output feedback control. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2019, 49, 3713–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaghmaie, F.A.; Lewis, F.L.; Su, R. Output regulation of linear heterogeneous multi-agent systems via output and state feedback. Automatica 2016, 67, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, H.; Sun, X. H∞ consensus for linear heterogeneous multi-agent systems with state and output feedback control. Neurocomputing 2018, 275, 2635–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Lewis, F.L.; Zeng, Z. Containment control for multiagent systems under two intermittent control schemes. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2019, 64, 1236–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wen, G.; Chen, G. Bipartite consensus tracking of heterogeneous multi-agent systems: A smooth output-feedback control approach. Automatica 2025, 178, 112363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ho, D.W.C.; Tang, Y.; Liu, Y. Quasi-consensus of heterogeneous-switched nonlinear multiagent systems. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2020, 50, 3136–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, J. Finite-time convergent gradient flows with applications to network consensus. Automatica 2006, 42, 1993–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Shi, P.; Xiang, Z.; Shi, Y. Finite-time consensus of second-order switched nonlinear multi-agent systems. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2020, 31, 1757–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Xian, J. Finite-time event-triggered consensus for non-linear multi-agent networks under directed network topology. IET Control Theory Appl. 2017, 11, 2458–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, B.; Han, Q. Prescribed finite-time consensus tracking for multiagent systems with nonholonomic chained-form dynamics. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2019, 64, 1686–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wang, H.; Yu, W. Distributed fast finite-time tracking consensus of multi-agent systems with a dynamic leader. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II 2022, 69, 2176–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, W.; Luo, L.; Zhong, S. Fixed-time consensus tracking for multi-agent systems with a nonholomonic dynamics. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2023, 68, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, B.; Jin, J.; Zheng, J.; Man, Z. Finite-time and fixed-time leader-following consensus for multi-agent systems with discontinuous inherent dynamics. Int. J. Control 2017, 91, 1259–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wen, C.; Guo, F.; Cai, H.; Su, H. Robust cooperative output regulation of uncertain linear multi-agent systems not detectable by regulated output. Automatica 2019, 101, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Peng, S.; Zhang, Z. Finite-time and fixed-time consensus of nonlinear stochastic multi-agent systems with ROUs and RONs via impulsive control. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 136630–136640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Jiang, Z.; Feng, G. Event-based consensus of multi-agent systems with general linear models. Automatica 2014, 50, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Liu, L. Cooperative output regulation of heterogeneous linear multi-agent systems by event-triggered control. IEEE Trans. On Cybern. 2017, 47, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Han, J.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, H. H∞ consensus for linear heterogeneous multiagent systems based on event-triggered output feedback control scheme. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2019, 49, 2268–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Pan, Y.; Li, H.; Cao, L. Dynamic event-driven ADP for n-player nonzero-sum games of constrained nonlinear systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 7657–7669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liang, H. Event-triggered predefined-time control for full-state constrained nonlinear systems: A novel command filtering error compensation method. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2024, 67, 2867–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Jiang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Shi, J. Fixed-time event-triggered and periodic event-triggered containment control for heterogeneous multi-agent systems under DoS attacks. Syst. Control Lett. 2025, 204, 106208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.; Yang, G. Input-to-state stabilizing control for cyber-physical systems with multiple transmission channels under denial of service. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2018, 63, 1813–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Xiang, Z.; Deng, W.; Yang, C.; Wang, Z. False data injection attacks detection in smart grid: A structural sparse matrix separation method. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2021, 8, 2545–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Fang, M.; Shi, P.; Wu, Z. Event-based secure consensus of mutiagent systems against DoS attacks. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2020, 50, 3468–3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Shi, P.; Huang, T.; Chakrabarti, P. Quantization-based event-triggered consensus of multiagent systems against aperiodic DoS attacks. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2023, 53, 3774–3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Shi, P.; Wen, X. Dynamic event-triggered approach for networked control systems under denial of service attacks. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2021, 31, 1774–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, G. Distributed dynamic event-triggered strategy for the consensus of multi-agent systems under asynchronous denial-of-service attacks. J. Frankl. Inst. 2025, 363, 108224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Ye, D. Observer-based fixed-time secure tracking consensus for networked high-order multiagent systems against DoS attacks. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 2018–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.H. On classes of summable functions and their fourier series. Proc. R. Soc. A 1912, 87, 225–229. [Google Scholar]

| Triggering Condition | Condition (36) | Corresponding Static Event-Triggered Condition |

|---|---|---|

| Mean triggered times for case (a) | 600 | 2465.5 |

| Mean triggered times for case (b) | 618.75 | 2559.5 |

| Source of the Method | This Paper | Reference [9] | Reference [25] | Reference [31] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heterogeneous Agent | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Event-Triggered Mechanism | Dynamic | N/A | Static | Dynamic |

| Type of DoS Attacks | Aperiodic Unknown | N/A | Periodic Known | Aperiodic Unknown |

| Convergence Type | Fixed time | Asymptotic | Fixed time | Asymptotic |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, J.; Jiang, H. Dynamic Event-Triggered, Fixed-Time Control for Heterogeneous Multi-Agent Systems with Hybrid DoS Attacks. Mathematics 2025, 13, 4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13244009

Han J, Jiang H. Dynamic Event-Triggered, Fixed-Time Control for Heterogeneous Multi-Agent Systems with Hybrid DoS Attacks. Mathematics. 2025; 13(24):4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13244009

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Ji, and He Jiang. 2025. "Dynamic Event-Triggered, Fixed-Time Control for Heterogeneous Multi-Agent Systems with Hybrid DoS Attacks" Mathematics 13, no. 24: 4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13244009

APA StyleHan, J., & Jiang, H. (2025). Dynamic Event-Triggered, Fixed-Time Control for Heterogeneous Multi-Agent Systems with Hybrid DoS Attacks. Mathematics, 13(24), 4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13244009