1. Introduction

Intellectual property (IP) is a concept used to protect innovation within a legal framework and possesses both moral and commercial value. In industry, acquiring real-world data for many practical tasks can be challenging. Deep learning models, particularly Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [

1], serve to address the issue of insufficient data by generating new instances, and they have been widely applied in many fields such as industry [

2,

3] and medicine [

4,

5]. The substantial costs associated with collecting training data for GANs (e.g., tracking objects over time or purchasing expensive sensors), coupled with the significant computational resources required for model training (e.g., 512 core Google TPUv3 for training BigGAN [

6]), contribute to the high value of the trained models.

Many researchers have attempted to claim IP rights by embedding specific watermarks in the parameters or output data of the models. For example, recent studies demonstrate various watermarking techniques: a fragile watermark can authenticate GAN integrity with

detection on ProGAN/DCGAN after only 1-epoch fine-tuning [

7]; box-free ownership verification using the discriminator’s feature hypersphere already achieves ≥ 75% AUC against

pruning or heavy JPEG/noise [

8]; and a joint black-/white-box scheme embeds visual logos (SSIM ≥ 0.9) and 56-byte signatures (BER = 0) into DCGAN/SRGAN/CycleGAN while surviving 30-epoch fine-tuning and watermark-overwriting attacks [

9]. Despite such progress, the dual capability of integrity certification and box-free, trigger-free verification remains unexplored in current literature, a void that this study intends to fill.

Existing methods are generally divided into black-box [

10,

11] and white-box approaches [

12,

13]. Black-box strategies refer to embedding digital watermarks into the input, which triggers the model to produce specific watermarked outputs. However, these methods require the copyright owner to interact with the suspect model via input-output queries. Consequently, misappropriation of non-public models cannot be verified, as external access is restricted. White-box methods embed the digital watermark into the parameters of the model. Ownership is verified by accessing these parameters and identifying specific characteristics (e.g., positive and negative signs that can be encoded as specified information). Consequently, white-box verification necessitates full access to the suspect model and its parameters. In practical scenarios, obtaining such comprehensive access is often infeasible.

Recently, the study of GAN-IPR [

9] model combines the above two methods to protect IP of GAN. The complete method endows the generator with dual capabilities for both black-box and white-box verification. Specifically, in the black-box setting, the model produces watermarked outputs upon receiving a specific trigger set. Simultaneously, for white-box verification, ownership information is encoded via the signs(positive/negative) of specific model parameters. Despite these advances, GAN-IPR still faces significant practical challenges in robustly protecting the IP of GAN. First, it is difficult to detect infringements every time. For example, infringers obtain profits by providing MLaaS services through online APIs, while concealing their activities by frequently changing virtual proxy IP addresses and domain names. It is impossible to monitor all the websites on the Internet daily. Second, even for suspected infringements that have been discovered, the process of collecting evidence and prosecuting for legal proceedings would be time-consuming and economically costly. Third, once some extremely important generated data or models are stolen, it would result in serious consequences. As mentioned in [

14], model theft may implicate national security issues, where the reactive nature of ‘law enforcement after discovery’ often leads to irreversible consequences due to the inherent temporal lag. Furthermore, under the influence of objective force majeure factors such as cross-border and COVID-19 epidemics, it is difficult to safeguard IP through laws. Furthermore, the conditions for some models to reach Nash equilibrium through training are very harsh, such as GANs and their variants. The infringer may steal a well-trained model solely for offline, unauthorized research without exposing any public interface, rendering detection impossible. The problems are particularly acute in GANs, because once the generator is stolen, the data can be generated indefinitely.

In order to solve these problems, we propose a novel end-to-end encrypted training method based on a self-adversarial strategy. Here, ‘self-adversarial’ implies that the model is optimized to act as an adversary against itself when the input is unauthorized, effectively destroying the generation quality by maximizing feature distance loss. This mechanism ensures that unauthorized inference yields degraded outputs, thereby rendering stolen model files practically useless. At the same time, this security measure incurs no performance penalty for authorized owners or licensees. Our method is also compatible with the methods proposed in [

9], preserving the capability for black-box and white-box watermarking as a complementary forensic measure for legal recourse.

We experimentally validate our proposed method.

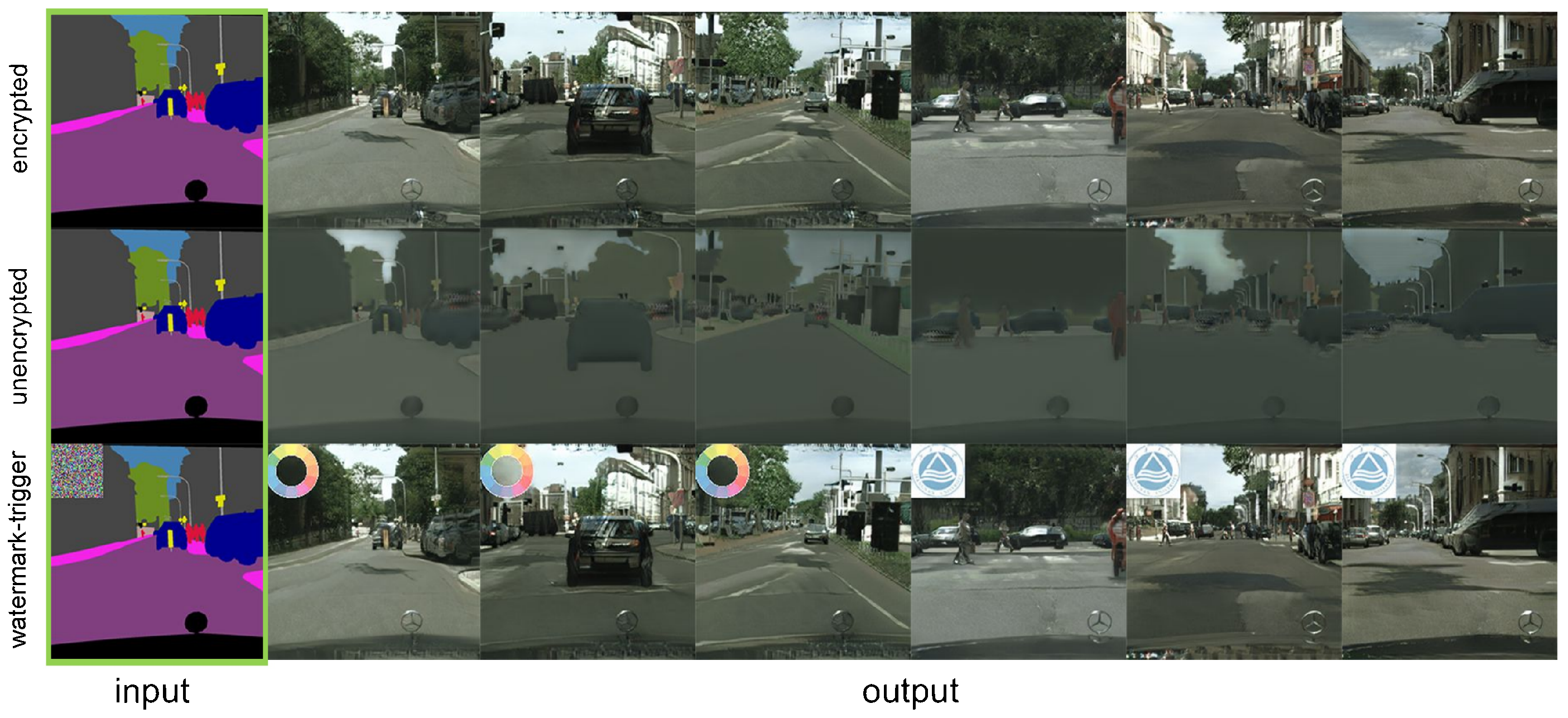

Figure 1 illustrates the effect of generating images for authorized, watermark-triggered, and unauthorized input. Notably, images generated from unauthorized inputs exhibit significant feature corruption. As shown in

Table 1, our method renders the DCGAN incapable of producing meaningful data under unauthorized conditions, resulting in drastically reduced classification accuracy. Conversely, authorized inputs yield classification performance comparable to the standard DCGAN baseline. In essence, our encryption training method ensures that any unauthorized use of the stolen generator produces severely degraded samples, causing general-purpose classifiers to exhibit high error rates. This visual effect is further exemplified in

Figure 2.

Table 2 shows the classification error rate of image data generated by unauthorized persons using the generator with and without encryption training. This serves as a concrete implementation of model IP protection. In addition, we verify the method’s robustness against common adversarial threats, such as fine-tuning and overwriting attacks. Our method can coexist with existing property rights claim methods, which can comprehensively protect the intellectual property rights of neural network models.

Our contributions are shown as follows.

Unlike existing IP protection methods that rely on passive post hoc verification—which permits stolen models to function unimpeded—EGAN (Encrypted GANs) introduces an active protection paradigm. Our method ensures that unauthorized inference yields structurally corrupted outputs, thereby rendering the stolen model functionally unserviceable without the correct key.

We propose a novel self-adversarial feature-separation mechanism. This compels the generator to learn disjoint distributions for authorized and unauthorized inputs, intrinsically embedding the protection into the model’s weights rather than relying on external wrappers or easily removable tags.

Whereas conventional watermarking techniques are often susceptible to ambiguity attacks or can be erased via fine-tuning, EGAN demonstrates superior robustness. Our experiments show that the corruption mechanism persists even after significant parameter modifications (e.g., fine-tuning), providing a level of security that outperforms contemporary model watermarking schemes.

2. Related Work

Currently, there are two main methods for verifying the property rights of CNN models: white-box and black-box verification methods. The former requires access to the complete model parameters to verify the property rights, while the latter relies solely on specific input values and outputs to complete the verification. Uchida et al. [

14] first proposed the embedding of digital watermarks into CNN models as a white-box verification method. E. Le Merrer et al. [

15] proposed a black-box verification method that maps specific user inputs to designated output categories to authenticate ownership. Y. Adi et al. [

16] presented a theoretical analysis of this black-box verification as a designed back-dooring. Moreover, studies such as [

2,

12,

13,

17] have demonstrated ways to improve the robustness of embedded watermarks, such as resistance to ambiguity attacks, fine-tuning, and pruning.

For GANs and their variants, Ding et al. [

9] proposed a set of IP verification methods, including both white-box and black-box verification. The black-box approach induces the generator to synthesize watermarked images upon receiving specific trigger inputs, while the white-box approach specifically encodes the symbols of the BatchNorm layers in the model. Yuan et al. [

7] introduce the first fragile watermark for GANs: a two-stage fine-tuning forces the generator to over-fit a secret label to a pre-defined watermark image, so any later parameter perturbation drops SSIM and raises MSE dramatically. Huang et al. [

8] abandon the “choose-inputs, check-outputs” black-box paradigm and instead train a hypersphere on the discriminator’s features to enclose the source generator’s distribution. Lastly, ref. [

18] used a variant of GAN to facilitate data augmentation on fetal heart rate (FHR) signals, aiming to preserve individual privacy through synthetic data. However, since the generator derives its distribution from real-world subjects, this method still poses a hidden danger of data privacy after the model is stolen.

However, it is crucial to note that the aforementioned studies focus primarily on claiming or verifying ownership. As noted in

Section 1, merely asserting or verifying intellectual property is insufficient to prevent potential infringement. We need to use brute force means to make the model unusable after being stolen by an unauthorized person. In other words, the model should deliver severely degraded outputs to unauthorized users, preventing it from performing its intended task, such as high classification error rates or extremely poor generated image quality, etc.

Recent years have witnessed the successful implementation of numerous techniques for generating adversarial examples against Deep Neural Networks (DNNs). Broadly, these methodologies fall into two categories: iterative type algorithms [

19,

20,

21,

22] and generative type algorithms [

23,

24,

25]. Iterative type algorithms operate by optimizing each individual sample to generate an optimal perturbation for adversarial attacks. These methods often yield a very strong attack effect. For example, ref. [

22] can cause a severe misclassification in a DNN classifier by altering just a single pixel. However, the need for per-sample iterations makes this method computationally expensive for large-scale adversarial sample generation.

Generative algorithms, on the other hand, train a specialized DNN to generate adversarial perturbations. This allows for rapid attack generation via a single forward pass, offering a substantial speed advantage over iterative counterparts. Notably, the method in [

25] is more general than prior works. Unlike task-specific methods (e.g., classification), its generated perturbations can simultaneously attack DNNs across a broad spectrum of downstream tasks. However, these generators are designed exclusively to synthesize perturbations and cannot generate high-fidelity, realistic data.

Watermarking techniques [

11,

14,

16] embed signatures into parameters or outputs to enable post hoc ownership verification, but the stolen model remains fully functional. Similarly, Model-locking/passport [

17,

26] schemes enforce key-conditioned inference, yet they do not prevent a generative model from emitting usable samples once it is executed without the key. Addressing these limitations, EGAN applied a generative protection mechanism that actively corrupts the internal feature maps for any unauthorized input, producing low-quality data that are unusable for downstream tasks. Simultaneously, it preserves a recoverable watermark, ensuring that post hoc ownership verification remains a viable legal recourse.

Recently, strategies focusing on model weight modulation and resistance to fine-tuning have gained attention. Fei et al. [

27] proposed OmniMark, which embeds fingerprints by modulating the convolutional kernels across multiple dimensions to achieve scalability. Similarly, Cui et al. [

28] introduced FT-Shield, a method specifically designed to survive unauthorized fine-tuning by integrating fine-tuning loss into the watermark generation process. However, these state-of-the-art methods typically aim to maintain attribution capabilities (traceability) after attacks. In contrast, EGAN focuses on access control, ensuring the model becomes functionally unusable without the correct key, rather than just verifiable.

Different from the aforementioned iterative or generative adversarial attacks which aim to fool a frozen model with perturbed inputs, our ’self-adversarial’ approach is a defensive training strategy. It embeds the adversarial objective into the generator’s loss function, ensuring the model internally corrupts its own features absent the correct encryption key, as illustrated in the CycleGAN example in

Figure 3.

3. EGAN

3.1. Threat Model

In our threat model, we assume that the attacker is capable of stealing the trained generative model, thereby gaining full access to the model files. This access enables the attacker to employ various exploitation techniques, including fine-tuning the model to alter its core functionality or adapt it for different tasks. Such capabilities reflect common vulnerabilities faced by model owners in computational environments and underscore the importance of safeguarding proprietary model architectures and data.

Although an attacker may acquire the model, they lack the secret key essential for its proper operation. This key, analogous to a cryptographic key, transforms input data to enable meaningful generation results. In the absence of this key, the attacker is restricted to providing raw, untransformed inputs to the encrypted generator. This renders the stolen model effectively useless for the attacker, as the generated data is degraded and unsuitable for any practical application.

In the hypothetical scenario where the attacker also obtains the secret key, the threat model incorporates additional defenses. The generative model embeds recoverable watermarks in both black-box and white-box formats, serving as post hoc verification mechanisms. These watermarks allow the rightful model owner to assert IP rights and pursue legal recourse, thus preserving avenues for ownership claims and enforcing intellectual property protections even in the most challenging circumstances.

By encompassing these threat dimensions, our approach not only fortifies the model against unauthorized use but also ensures a comprehensive framework for asserting ownership and maintaining privacy.

3.2. Overview of the Process of Model Protection

The basic components of GANs and their variants are the generator network and the discriminator network. The objective of the trained generator is to synthesize high-fidelity data, such as realistic images. Consequently, our proposed method specifically targets the encryption of this trained generator model.

Under our methodology, the process of protecting GANs is illustrated in

Figure 4. The model owner selects a transformation as a key, which is then integrated into the cryptographic training of the GANs. Consequently, all inputs are transformed with the key before being processed by the generator. This ensures that the generator functions correctly only when presented with encrypted inputs that have been transformed with the corresponding key. The owner can distribute the key to the authorized party through a specific protocol or encrypted communication. If unauthorized persons steal the generator model, they cannot obtain expected outputs using inputs for normal GANs. Even if the infringer successfully acquires both the model and the key to generate valid outputs, the model owner can still claim IP rights and use legal weapons through black-box and white-box verification methods [

9].

In essence, our approach involves applying a key-based transformation to all inputs during both model training and validation prior to their entry into the model. The remaining workflow follows conventional training procedures, with the exception of a feature distance regularization term incorporated into the loss function, which will be analyzed in

Section 4. The transformation must strike a balance: it should be sufficiently strong to significantly degrade the output quality for unauthorized users employing unencrypted inputs, yet not so extreme as to undermine the model’s original performance. Additionally, the transformation should offer a sufficiently large key space to prevent easy deciphering. In this section, we demonstrate feasible encryption transformations and their effects on several widely-used GAN architectures, including DCGAN, CycleGAN, and SRGAN.

Our encryption transform functions as an asymmetric key-lock mechanism: the generator synthesizes high-fidelity outputs only if the input is transformed by a secret key; otherwise, a feature-level corruption regularizer is employed to render the outputs unusable. In this paper, we refer to this mechanism as “self-adversarial”. Specifically, this strategy guides the model to maximize the feature-level discrepancy between the feature maps produced by authorized inputs and those produced by keyless (unauthorized) inputs. To implement this mechanism, we introduce a new loss term that maximizes the Frobenius norm of the feature maps at the intermediate layers of the generator. Denote

as the original input to our generator

G, and denote

f as our key transformation, then the keyed input,

will be denoted as

. Extracting

G at layer

ℓ we obtain the feature map of keyless input

and that of keyed input

, which we assume to be reshaped in matrix form, such that

, with

and

the spatial dimensions of the feature map, and

its number of channels. From this, our Feature Separation layer loss is defined as

where

denotes the Frobenius norm.

Our objective is to maximize

to induce structural corruption in the outputs of keyless inputs. However, to prevent the magnitude of

from overwhelming the primary convergence of the model, we normalize

to map it to

. Consequently, our maximizing feature separation loss term is defined as

We detail the inference protocol in Algorithm 1 to clarify the deployment and usage of the trained model.

| Algorithm 1 Inference Protocol of EGAN |

Input: : input data provided by user; G: Trained Encrypted Generator; : Key provided by user (if any).

Output: Generated data y.

- 1:

function Inference() - 2:

▹ based on Equation (3) - 3:

▹ Apply key transformation - 4:

▹ Generator forward pass - 5:

return y - 6:

end function

|

3.3. Protection Process for DCGAN

To verify that our method preserves the model’s ability to claim property rights through watermarking, we adopt the same architecture mentioned in [

9], SN-GAN [

29], which is a variant of DCGAN. The input to DCGAN [

30] is a latent vector randomly sampled from a standard normal distribution,

, which is first processed by a fully connected (FC) layer to upsample its dimensions prior to convolutional processing. We designate the output of the FC layer as the input of the model because it has enough dimensions to provide a sufficient space. In our experiments, the input dimension is 8192 (

) when the output image size is

, and 32,768 (

) when the output image size is

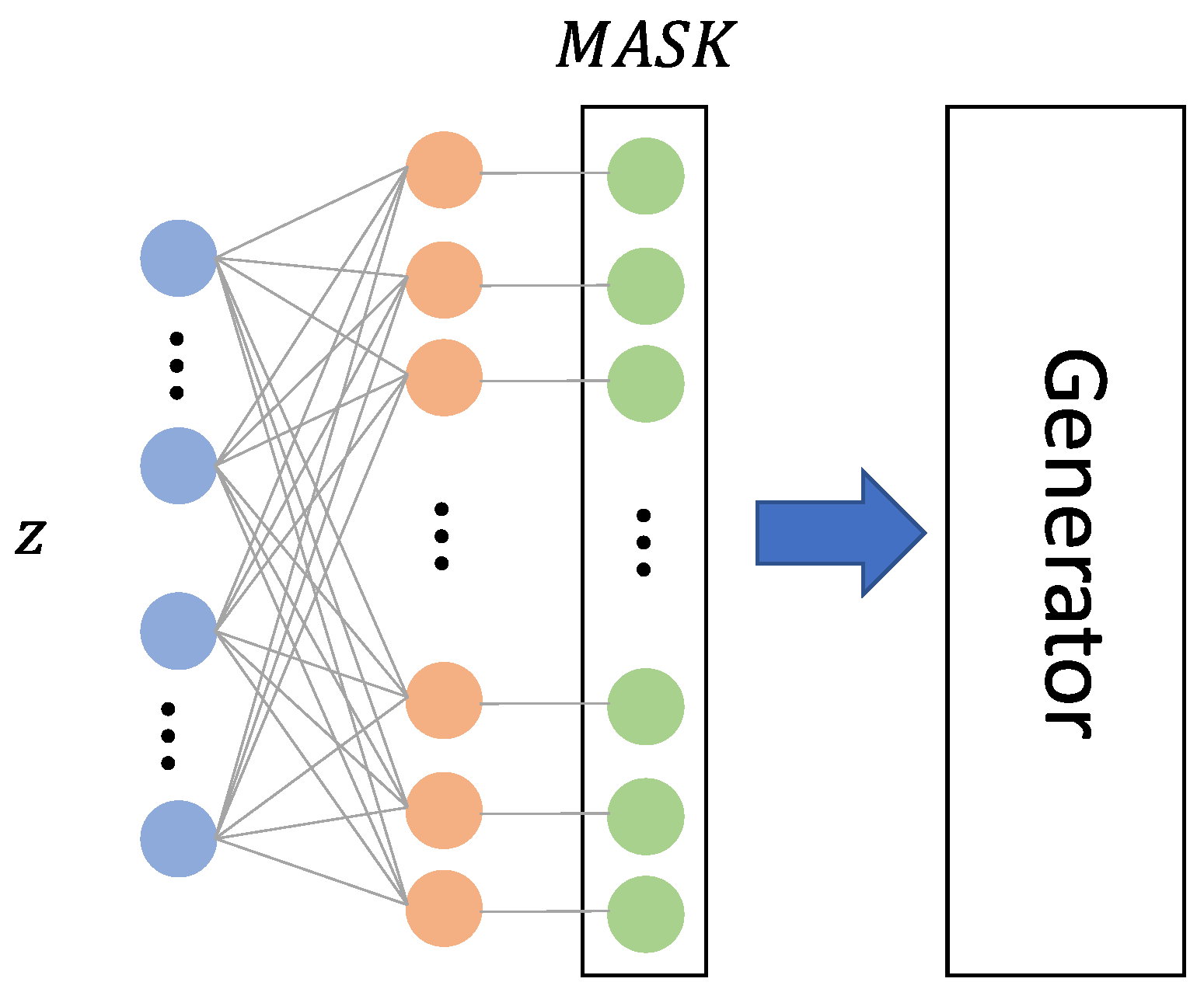

. The key transformation is implemented via a masking strategy that perturbs 256 randomly selected dimensions by adding or subtracting a fixed constant. This transformation serves as the cryptographic key, enforcing a dependency where the trained model produces valid mappings only when conditioned on this specific perturbation. Formally, we define the input transformation function,

f, which maps the output vector of the FC layer to a keyed vector (

) as follows (shown in

Figure 5):

The bitmask in the above formula controls which dimensions remain unchanged and to which dimensions a fixed constant c is added. The constant c can be chosen to be a positive or negative number that deviates significantly from 0 because our intention is to change the input distribution. We uniformly choose in our experiments. We set 256 dimensions in the bitmask to have values of 0, and the remaining dimensions are set to 1. Here, represents the number of dimensions in . Therefore, the size of our change selection space is or , while the selection space of a common 6-digit password is .

To ensure consistency with the baseline, we adopt the Spectral Normalization GAN (SN-GAN) [

29], which is a variant of DCGAN. The original objective function of the generator is defined as follows:

The loss term for the watermark is defined as [

9]:

We incorporate the regularization term for feature separation (Equation (

2)), and the objective function of encrypted DCGAN is defined as:

where the hyperparameter

controls the watermark quality when triggered, and

controls the severity of degradation for the non-key output. The complete training procedure is summarized in Algorithm 2.

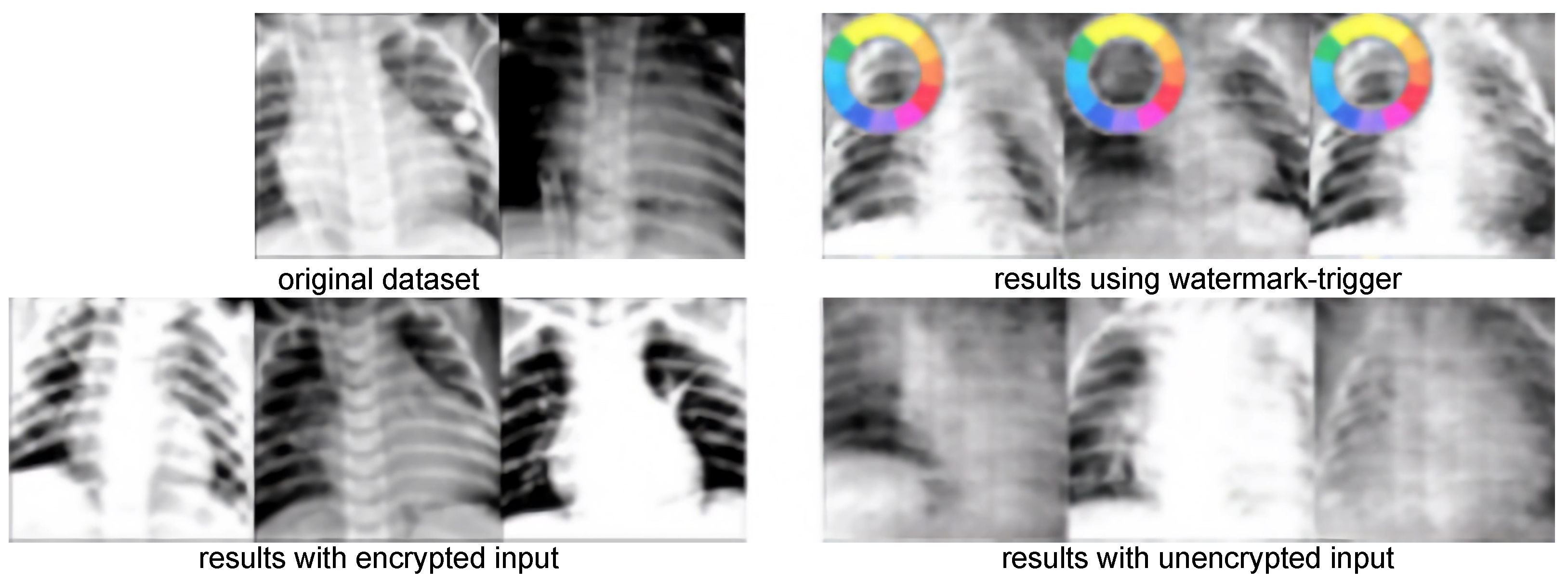

Figure 6 illustrates this degradation effect on the CTU-UHB dataset.

| Algorithm 2 Training Pseudocode of EGAN |

Input: : original input; G: Generator; D: Discriminator; f: mask for encryption (Equation (3)); : mask for the watermark trigger.

Output: Trained Generator G- 1:

repeat - 2:

Compute trigger input: - 3:

Compute encrypted input: - 4:

Obtain feature maps at layer ℓ: and - 5:

Pass to D to compute GAN loss using Equations ( 4) and ( 7) - 6:

Compute feature separation loss using Equations ( 1) and ( 2) - 7:

Compute watermark loss using Equation ( 5) - 8:

Compute gradients and update weights of G and D - 9:

until convergence - 10:

return

G

|

3.4. Protection Process for CycleGAN

To clarify, in CycleGAN, there are two pairs of generators

and discriminators

. Each

takes in an image as input and produces an image as output. We choose one of these generators as our protection target. To encrypt the input image, we first randomly select a set of positions, and then apply a predetermined transformation to the pixel values at these positions (for example, adding or subtracting a constant). The transformation method and position set together form the encryption key. This results in the encrypted input image, denoted as

. Similar to the previous section, we can represent this process using Equation (

3), where

now represents an image matrix instead of a one-dimensional vector.

The objective function of cyclegan is as follows.

We introduce a regularization term for feature separation and retain the regularization term used to embed the watermark, so the objective function of CycleGAN is defined as:

3.5. Protection Process for SRGAN

SRGAN is widely recognized as a pioneering framework in the field of image super-resolution. Its generator

, is specifically designed to reconstruct high-fidelity high-resolution images from low-resolution inputs. When using the trained

for super-resolution tasks, the input dimensions are often variable, while the super-resolution scale factor remains fixed. For instance, if we input a

image, we can get a

super-resolution image, and if we input a

image, we can get a

super-resolution image. Consequently, the fixed-position spatial transformation typically employed in architectures like CycleGAN is ill-suited for this scenario, as it relies on rigid spatial alignment that does not exist here. Instead, we select one or several channels of the input image and transform the entire channel to avoid the influence of different input sizes. The visual comparison is shown in

Figure 7. The objective function of protected SRGAN is denoted as:

4. Experimental Results

In order to distinguish the original baseline models, the watermark baseline models and our proposed encryption models, we denote the watermark baseline models with subscript

w (i.e.,

,

,

), and our proposed encrypted models with a subscript

(i.e.,

,

,

). It should be noted that the watermark here contains both the black-box and white-box settings proposed in [

9]. The original text is represented by subscripts

w and

s respectively, but we use the subscript

w here to unify them. In addition, for results generated from valid inputs processed with keys, we add * in the subscript to denote them.

4.1. Hyperparameters and Benchmark

We demonstrate our proposed encryption method on three GAN models: DCGAN, CycleGAN, and SRGAN. To ensure the generalizability and reproducibility of our results, we chose classic publicly available datasets, avoiding the potential extreme features of domain-specific datasets that may affect model performance.

For fair comparison, all hyperparameters and network architectures follow the original work of each GAN model. In all experiments, the models were trained for 100 epochs with the Adam optimizer ( = 0.5, = 0.999) and a constant learning rate of . The batch size was 64 for DCGAN/CycleGAN and 16 for SRGAN. The feature separation loss is computed on the generator’s penultimate convolution block. We observed that applying the loss to shallower layers hindered model convergence, whereas applying it solely to the final pixel layer failed to capture high-level semantic discrepancies. Therefore, the penultimate layers were selected to maximize perceptual degradation in unauthorized outputs while maintaining training stability.

For DCGAN, we use CIFAR10 (

), CTU-UHB (

), CUB200 (

), and ChestXray2017 (

) as benchmark datasets (sample results are shown in

Figure 8). For the CTU-UHB dataset, we transform the 1D time series data into 3 channels, similar to color images, and apply the same training procedure as for CIFAR10.

For CycleGAN, we follow [

9] and train the model on the Cityscapes dataset [

31], but only protect one of the generators (labels → photos). We introduce an input transformation function and a feature separation regularization term, while maintaining all other original hyperparameters and configurations as described in [

32].

For SRGAN, we adhere to the experimental setup in [

9] by randomly sampling 350k images from Imagenet [

33] for training. The other hyperparameters remain the same as the baseline SRGAN [

34].

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

To ensure that our method does not compromise the original performance of the GANs, we utilized several metrics to evaluate the quality of the generated images. For the image generation task using DCGAN, we calculated the Frechet Inception Distance (FID) [

35] between the generated and real images. For CycleGAN, we measured the FCN-scores as presented in [

32] on the Cityscapes label → photo dataset, which includes per-pixel accuracy, per-class accuracy, and class intersection-over-union. For image super-resolution with SRGAN, we used peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) and structural similarity index (SSIM) as our metrics. These metrics were comprehensively evaluated on standard benchmark datasets, including Set5, Set14, and BSD100.

To verify that our method preserves the capability to embed watermarks and claim property rights, we used the same watermark evaluation method as [

9]. We measured the quality of image watermarks using SSIM between the generated watermark and the ground truth watermark, denoted as

. Additionally, the integrity of the weighted sign signatures is assessed via the Bit Error Rate (BER).

As shown in

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5, the performance of the protected DCGAN, CycleGAN and SRGAN (i.e.,

/

/

) is comparable to the baselines on several datasets. Moreover, our method guarantees that these models produce significantly degraded results when subjected to unencrypted inputs.

4.3. Necessity of Regularization Term

In this section, we demonstrate that while training models exclusively on encrypted data inherently restricts their functionality to encrypted inputs, the incorporation of the feature distance regularization term (Equation (

2)) remains critical. This regularization term ensures more robust destruction of generated data quality, preventing unauthorized individuals from using it for various downstream tasks. Furthermore, the term enhances the model’s resistance to fine-tuning attacks.

Experiments demonstrate that without the feature distance regularization term during training, unauthorized individuals can fine-tune the model to significantly reduce its encrypted properties, thereby allowing them to use unencrypted inputs to obtain results comparable to the expected outputs. In contrast, incorporating the feature distance regularization term effectively prevents unauthorized fine-tuning from yielding usable outputs.

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8 show that the absence of this term allows adversaries to obtain results comparable to those from encrypted inputs. With the term applied, however, the quality of illicitly obtained results severely degrades, confirming the failure to achieve expected generation quality. Moreover, our method maintains the robustness of the model’s watermarking capabilities (black box and white box), with high image watermark quality

and zero model symbol watermark bit error rate BER for the fine-tuned models.

We observe that the BER consistently remains 0 across our experiments (

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8). This is because our work follows [

9], which uses the scaling factors

from the batch normalization layer as signatures, and converts

into ASCII characters to serve as a model watermark for protection. This approach is taken because, if someone attempts to steal the model parameters for an attack, the

values are unlikely to undergo positive or negative shifts due to the attack, thus keeping the ASCII characters used as the watermark unchanged. Since the BER (bit-error rate) measures the difference between the original watermark and the post-attack watermark, and given that the watermark remains unchanged in adversarial scenarios (as detailed in [

9]), its value is 0.

4.4. Key Transform

As mentioned in

Section 3.2, the key transformation should strike a balance: it should be neither too aggressive nor too simplistic. This section aims to verify this by showcasing the importance of slightly targeted designs for the key transformations of GANs. The required input data types may vary depending on the GAN, such as Gaussian noise for DCGAN or image data for CycleGAN and SRGAN. Nonetheless, the key transformations of each GAN can be seen as a mask, with Equation (

3) expressing the mathematical formulation. Notably, the bits with a value of 1 in the

vector do not alter the original input

, only the bits with a value of 0 affect the corresponding bits of

. We designate the bits with a value of 0 in

as the significant bits of the mask. Therefore, when the constant

c remains constant, a larger number of significant bits in the vector

implies a greater deviation in the input distribution.

Table 9 presents the FID scores of EN-DCGAN on the CUB200 dataset with different numbers of significant mask bits. Results indicate that EN-DCGAN achieves generation quality comparable to or exceeding the baseline when the number of significant bits ranges from 256 to 512. However, an insufficient or excessive number of effective bits results in an increased FID score and poor image quality.

4.5. Comparison

Compared with prior GAN-protection baselines, EGAN is the only method that actively disables an unauthorized copy instead of merely leaving an audit trail. GAN-IPR [

9], Box-free [

8] and Fragile [

7] all allow a pirate to keep generating high-quality images; their protection is reduced to post hoc verification. EGAN, by contrast, forces the model to emit unusable noise when the secret key is absent, and this “fail-closed” behavior survives fine-tuning, pruning and even white-box parameter overwriting. Consequently, EGAN shifts the risk–reward calculus: a stolen model has zero commercial value, so the incentive for theft is removed at source rather than punished afterwards.

5. Discussion

EGAN efficiently processes trigger inputs through a key-lock transformation mechanism, ensuring that meaningful outputs are exclusively reserved for authorized users. This system applies specific key-based transformations to inputs before they reach the generator, optimizing security with a regularization term that maximizes feature separation loss. Consequently, unauthorized outputs are structurally corrupted. For validation against stolen GANs, EGAN integrates the proactive corruption of unauthorized outputs with reactive verification capabilities—facilitated by compatibility with black-box and white-box watermarking techniques, thereby significantly bolstering intellectual property protection. By combining these strategies, EGAN not only maintains the operational integrity for legitimate users but also robustly guards against misuse, securing both the models and their generated data.

Currently, our method has been verified primarily on public datasets (e.g., CIFAR10, CTU-UHB, Cityscapes). In the future, we aim to explore the scalability and robustness of our approach in more specialized and practical domains. Given that data in fields such as medical imaging and industrial inspection are often difficult to acquire and possess high commercial or privacy value, we plan to conduct experiments on these high-stakes datasets. This will allow us to further validate the real-world applicability of our self-adversarial protection mechanism in safeguarding sensitive and high-value intellectual property.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we presented EGAN, a robust framework designed to safeguard the intellectual property of deep generative models against unauthorized usage and theft. By integrating a secret-key-dependent encryption mechanism into the model architecture, EGAN ensures that high-fidelity generation is exclusive to authorized users, while unauthorized access results in degraded, noise-like outputs. The contributions of our EGAN are as follows: (1) Distinct from passive verification, we introduce an active protection paradigm where unauthorized inference results in structurally corrupted outputs. (2) We propose a novel self-adversarial feature-separation mechanism that physically embeds protection into the model weights rather than relying on external wrappers. (3) We demonstrate that EGAN offers superior robustness against fine-tuning compared to existing watermarking schemes while it maintains the original generative performance for authorized users.

Regarding ethical deployment, we recommend (i) embedding keys within authenticated software, (ii) maintaining comprehensive logs of all decryption activities, and (iii) restricting model licenses to non-safety-critical research domains with third-party escrow, thereby balancing strict IP protection with safe usage.