1. Introduction

In the rapid development process of the modern food industry, prefabricated food, with its obvious advantages of convenience, standardization, and diversification, meets the demand of consumers for high-efficiency and high-quality food under the current fast-paced life model and quickly wins the favor of the market and realizes the leapfrog expansion of scale. According to industry statistics, the market size of China’s prefabricated food has climbed to 680 billion yuan in 2024, a record high. Based on the current market growth trend and consumption demand trend forecast, this scale will exceed the trillion-yuan mark by 2026, reaching 1072 billion yuan, fully demonstrating the strong development vitality and broad market prospect of the prefabricated food industry.

However, behind the rapid expansion of the industry scale, the short board of development brought by rapid expansion has also gradually surfaced, among which food safety problems, such as the imperfect quality control system of raw materials and frequent hygiene hidden dangers in the production and processing links, are particularly prominent [

1,

2,

3,

4]. At the upstream raw material supply end, there are problems such as unclear origin source, non-uniform testing standards for pesticide and veterinary drug residues, and chaotic batch management, while at the middle production and processing link, some enterprises are facing loopholes such as simplified process flow for cost reduction, substandard workshop hygiene conditions, and inadequate temperature control of cold chain storage and logistics. These problems not only pose direct potential risks to the health of consumers but also trigger a crisis of public trust in prefabricated food, and this becomes a key obstacle that restricts the industry from “scale expansion” to “quality improvement” and the realization of long-term healthy development. Therefore, the construction of a chain-wide food safety management system and the improvement of quality control standards covering raw material procurement, production and processing, warehousing and logistics, terminal sales, and other links have become important tasks to be solved urgently in the prefabricated food industry.

With its convenience and standardization advantages in catering scenes, the popularity of prefabricated dishes is increasing [

5,

6,

7]. At present, many scholars have carried out research on the quality and safety of prefabricated food. Shen et al. revealed through a questionnaire survey system that nutrition balance, technology safety, and governance trust have adverse effects on consumers’ perceived risk of safety of prepared food [

4]. Based on the MOA theory and SEM model, Hou et al. explored the influencing factors of consumers’ willingness to consume prefabricated food in China, and found that motivation, opportunity, and ability positively affected consumption willingness, and the latter two mediated motivation through convenience and health factors [

8]. Guo et al. proposed to apply the 3D-printing technology to food for the production of prefabricated food to solve the problems of microbial contamination, poor nutrition quality, and product standardization [

9]. He et al., based on two (risk media: new media/traditional media) × two (consumption promotion situation: strong/weak) inter-subject investigation experiments, explored the shaping mechanism of risk media on consumers’ prefabricated food safety risk perception and tested the mediating effect of food safety awareness and the moderating effect of promotion intensity. The results showed that media environment and promotion intensity jointly affect this risk perception [

2].

Industrial processing has exacerbated the complexity of the food supply chain, and consumer concerns about food-related risks have significantly increased their focus on food traceability [

10]. As an effective tool to ease information asymmetry and ensure food quality and safety, traceability information sharing, the core link of the traceability system, has been a research focus in the field of food supply chain management for a long time, and it has been a broad concern in academia. Obonyo et al. discussed the traceability information sharing problem under the ternary relationship of the food supply chain with the background of Kenya’s dairy supply chain and found that traceability information sharing has a differentiated impact on the development of social capital [

11]. Ersoy et al. believe that traceability information-sharing technology can help more efficient knowledge sharing practice and thus promote the improvement of an efficient circular food supply chain [

12]. Christensen et al. discussed the multidimensional impact of product attributes, demand conditions, supply patterns, and planned environmental characteristics of food manufacturers on information-sharing technology in food supply chains [

13]. Yu et al. constructed a food supply chain game model with suppliers and retailers to study the profit trade-off decision between suppliers’ quality disclosure and non-disclosure, considering the effect of asymmetric demand information in the vertical direction of the food supply chain on suppliers’ quality disclosure [

14]. The implementation of information sharing and related application technologies is regarded as the biggest challenge for food supply chain safety incident prevention and control. Van Beusekom-Thoolen et al. proposed the implementation of information sharing and related application technologies on the ground, which is regarded as the biggest challenge for food supply chain safety incident prevention and control [

15]. Liu et al. studied the optimal decision-making and coordination of the two-channel food supply chain under information symmetric and asymmetric scenarios by using Stackelberg game theory and backward induction. After designing the coordination contract, they found that the information asymmetry will aggravate the deviation of the optimal decision-making of the supply chain members, the information sharing is only beneficial to the manufacturer, and the improved revenue-sharing/cost-sharing contract is an effective coordination mechanism [

16]. Aiming at the multiple challenges faced by the food supply chain, Gruzauskas et al. proposed an information-sharing strategy based on interconnected vehicle technology and simulated the scene through the distribution model to improve food quality and enhance the sustainability and resilience of the supply chain [

17]. León-Bravo and others focus on the short food supply chain, explore the operation practice of geographical, relational, and information proximity and its sustainability relevance, and analyze the realization form of information sharing, its synergy with relational proximity, and the internal mechanism of the three to jointly promote the sustainable development of the supply chain after establishing the proximity upstream and downstream of the supply chain [

18]. Sharma et al. believe that traceability of the food supply chain and information sharing for customers have a positive impact on visibility; visibility not only promotes the adoption and response speed of sustainable practices, but also positively affects supply chain performance. However, information sharing with customers had no significant impact on performance, and information sharing with suppliers had no significant correlation with visibility [

19].

Profit distribution, as the core element of supply chain management research, is crucial to the stable development of the prefabricated food supply chain. When Huang et al. studied information sharing in supply chain coordination, they quantitatively evaluated the impact of reliability and availability of information transmission on supply chain profits, which provided a theoretical basis for the correlation research between traceability information sharing and profit distribution in the prefabricated food supply chain [

20]. Hong et al. analyzed the impact of information sharing on supply chain competition and supplier profit from the perspective of information-sharing types, which is helpful to understand the mechanism of different types of traceability information sharing on profit distribution in the prefabricated food supply chain [

21]. Diao et al. paid attention to the impact of competition between the sharing platform of the agricultural supply chain and retailers on profit, which provided a reference for similar research on channel relationship and profit distribution in the prefabricated food supply chain [

22]. There are also a few scholars who apply the Shapley value method to food supply chains; for example, Gopalakrishnan and Sankaranarayanan apply the Shapley value method to investigate the practical feasibility of identifying bilaterally implementable security cost-sharing arrangements in relevant alliances for pollution problems in food supply chains or data leakage problems in technology networks [

23]. However, due to the fact that food sales involve both online and offline channels, scholars have made more use of the differential game method to analyze this. Li et al. focused on the fresh food online and offline dual-channel supply chain under the disturbance of consumers’ quality preferences, constructed centralized and decentralized decision-making models, explored the flexible decision-making mechanism of price, quality, and output, and achieved supply chain coordination through revenue-sharing contracts. It was proven that considering the disturbance could improve the profit of members, centralized decision-making was more advantageous, and that there was a flexible decision-making interval [

24]. Li et al. considered the online and offline demand function of the relationship between promotion and substitution, analyzed the optimal decision-making and parameter effects of promotion intensity and online discount under three decision-making models of platform operation, and found that the centralized model had the highest supply chain profit, and the relationship between optimal promotion intensity and discount was regulated by a substitution coefficient and an online promotion influence coefficient [

25]. Guo and others focused on the challenges of dual-channel operation of food retailing, based on the utility model, analyzed the optimal order volume and price discount of retailers under different transportation policies, revealed the impact of factors such as freight on pricing, and found that low freight rates can achieve a “win–win” situation and high freight rates can lead to target conflicts, while reasonable allocation of safety stocks and adjustment of transportation policies can improve efficiency, reduce waste, and enhance supply chain resilience [

26]. Lin and Januardi combine multiple logistic regression, the logit model, and the Stackelberg competition bi-level programming model to analyze the customer channel preference, willingness to pay, and the pricing mechanism under competition in the dual sales channel system. It is found that channel price has a non-linear impact on both, and traditional retailers as leaders have higher profit [

27]. A systematic comparison of the above-mentioned studies is summarized in

Table 1.

To sum it up, the attention paid by the existing research to the specific field of prefabricated food is still relatively insufficient, and the related discussions are mostly focused on basic aspects, such as technical improvement, method innovation, and identification of influencing factors. At the same time, although many scholars have carried out cross-method research under multiple scenarios for the influencing factors, action mechanism, practical challenges, and optimization path of information sharing in food supply chains, few have systematically and deeply analyzed the internal coordination mechanism and practical implementation path of traceability information-sharing behavior in supply chain coordination from the dual perspectives of supply chain participants, such as suppliers, manufacturers, retailers, and platform parties, and the overall performance optimization of the supply chain.

In view of this, this research takes the prefabricated food supply chain as the research object, based on the core orientation of “constructing a traceability system to crack the pain points of quality and safety”; the traceability system can realize the whole process of the traceability of product information and provide key support to protecting the rights and interests of consumers, enhancing the enterprise’s crisis-response ability and the industry’s overall reputation—focusing on the core of the traceability information sharing system, aiming at the problems of sharing obstacles and system efficiency limitations caused by the difference in interest demands and information asymmetry between manufacturers and retailers, and aiming at optimizing the sharing coordination mechanism and profit distribution scheme. Research and build a two-level supply chain model consisting of manufacturers (responsible for production, core traceability information sharing, and dual-channel operation functions) and retailers (responsible for sales and terminal traceability information sharing functions), simultaneously incorporate online and offline dual-channel sales models, set both parties as rational economic entities and form four decision scenarios around traceability information sharing, and clarify that information sharing affects market demand and revenue distribution patterns through its effect on product quality and brand goodwill. In terms of research methodology, a dynamic differential game analysis model is constructed, and the Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman (HJB) equation, which can effectively depict the dynamic optimization problem under the continuous time dimension and accurately capture the interactive impact of goodwill accumulation and product quality, the coordination mechanism, and profit distribution logic of traceability information-sharing behavior, are systematically analyzed, and at the same time, the Shapley value method is innovatively integrated to scientifically and reasonably distribute the income of supply chain participants after forming a strategic alliance, which provides a theoretical support for the income distribution of food supply chain. On this basis, the study further focuses on the online and offline dual-channel scenarios, exploring the impact of the four decision-making modes on traceability sharing degree, market share, and profit distribution results, as well as the difference in profit effect between manufacturers’ channel sharing behavior and goodwill accumulation.

The contribution of this research is mainly reflected in three aspects:

Integrate the “multi-agent game” with the “online and offline dual channels” scenario of the pre-cooked food, anchor its “short-term protection and long-term chain” characteristics and traceability pain points, embed specific parameters such as freshness traceability weights, and construct a customized game model to solve the problem of insufficient pertinence of pan-food research to the pre-cooked food category.

Establish a coupling model of “dual-channel development and evolution-dynamic fluctuation of information asymmetry-real-time adaptation of coordination mechanism”, quantify the transmission path of channel structure adjustment to traceability-sharing intention, design an incentive coefficient mechanism dynamically optimized with the proportion of channels, and solve the core problem of a lack of flexibility in the traditional mechanism.

Build a four-order conduction model of “traceability behavior-quality signal-trust accumulation-goodwill premium”, prove that traceability sharing can be converted into a quality signal to form goodwill premium, and clarify the value-added path from traceability to profit.

2. Basic Assumptions

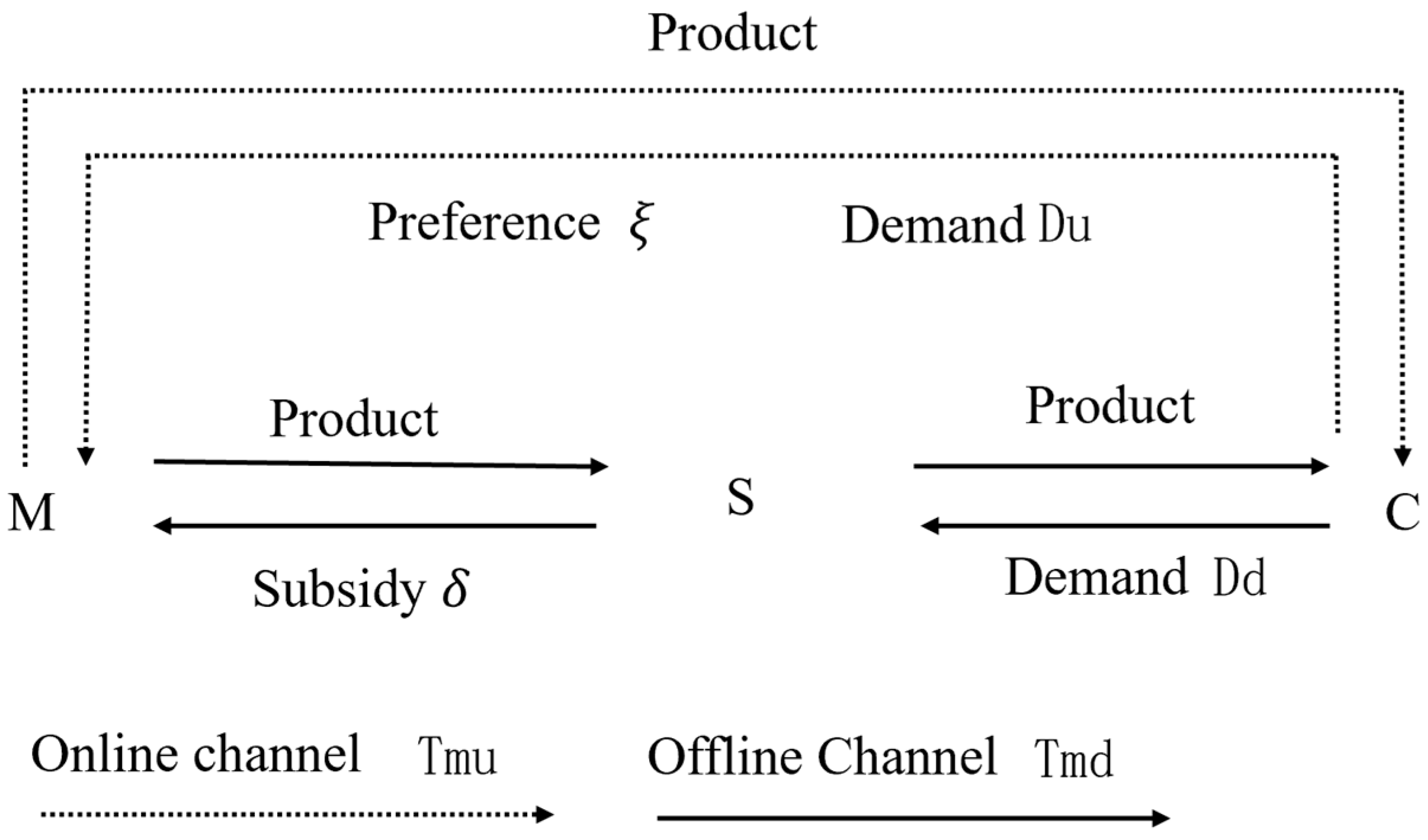

This study focuses on the coordination mechanism of information-sharing behavior within the traceability system of the prefabricated food supply chain, specifically between manufacturers and retailers. In this system, the manufacturer (denoted as m) is responsible for sharing traceability information, such as enterprise certification, production process details, logistics and warehousing data, and quality inspection reports. The manufacturer operates through traditional offline channels—supplying products to retailers—and online direct-to-consumer channels. The retailer (denoted as s), in turn, shares traceability information, such as product acceptance data and consumer feedback. The logical framework of this information-sharing coordination mechanism is depicted in

Figure 1.

The notation used throughout the paper is defined in

Table 2. This study establishes a two-level supply chain model composed of manufacturers and retailers, in which the manufacturer adopts online and offline sales channels. At any time t, the manufacturer’s traceability information-sharing behavior is divided into online and offline components. All members of the supply chain are regarded as rational economic entities, each having full knowledge of the other’s information-sharing costs and profit-related parameters. According to the literature [

28,

29,

30], the cost functions of the traceable food manufacturer through online and offline channels, as well as those of the retailer, can be represented as follows:

,

, and

, where

is a positive constant and serves as the key coefficient influencing the cost of information sharing among supply chain members.

On the one hand, the manufacturer’s traceability information-sharing behavior directly affects product quality. The implementation of the traceability system ensures that prefabricated food complies with national standards during the transportation process [

31,

32,

33]. As a dynamic variable

, the rate of change in product quality over time can be expressed as follows:

In Equation (1), Tmu and Tmd represent the manufacturer’s traceability information-sharing behaviors in the online and offline channels, respectively. denotes the impact coefficient of the manufacturer’s online information-sharing behavior on product quality, whereas reflects the impact coefficient of the offline information-sharing behavior on product quality. represents the decay coefficient of product quality when the manufacturer does not engage in traceability information sharing, due to factors such as cost reduction and insufficient quality control. defines the initial level of product quality.

On the other hand, the retailer’s traceability information-sharing behavior and product quality influence the goodwill of prefabricated food. Based on a modification of the classic Nerlove–Arrow goodwill model [

34], the dynamic evolution of goodwill can be expressed as follows:

In Equation (2),

denotes the goodwill of prefabricated food at time t;

represents the coefficient reflecting the effect of product quality on goodwill;

denotes the retailer’s traceability information-sharing behavior;

indicates the coefficient representing the effect of the retailer’s traceability information-sharing behavior on goodwill;

represents the decay coefficient of goodwill or the effect of consumer forgetfulness on goodwill [

35]; and

denotes the initial level of goodwill.

Given that the demand for prefabricated food is linearly related to its quality and goodwill, total market demand consists of three components: the baseline market demand, product quality, and goodwill. According to the literature [

36], product quality and goodwill influence consumers’ purchasing intentions. When the manufacturer and retailer engage in traceability information sharing, the demand functions for the online and offline channels can be expressed as follows:

In Equations (3) and (4), represents the initial market demand; ξ denotes the consumer preference coefficient for online channels; reflects the degree to which product quality influences the demand for traceable food; represents the effect of goodwill on the demand for traceable food; and , , and denote the unit marginal revenues of the manufacturer’s online and offline channels and of the retailer, respectively. In addition, the manufacturer and the retailer adopt the same discount rate for evaluation.

4. Comparative Analysis

Based on the results of the previous models’ construction and solution, as summarized in

Table 3, the following conclusions can be drawn:

Lemma 1.

For product quality

:

when

, Q1 shows an increasing trend.

when

, Q2 shows an increasing trend.

when

, Q3 shows an increasing trend.

when

, Q4 shows an increasing trend.

2.For goodwill

:

when

, G1 shows an increasing trend.

when

, G2 shows an increasing trend.

when

, G3 shows an increasing trend.

when

, G4 shows an increasing trend.

These trends are consistent with the optimal solutions presented in Table 3. Corollary 1. As time progresses—thus,

—product quality and goodwill eventually reach a steady state. According to the steady-state values

and

, consumers’ preference for prefabricated food with high quality and good reputation increases over time, leading to a continuous rise in product sales in the market and, consequently, an increase in overall profit.

Lemma 2. Online traceability information-sharing behavior of prefabricated food manufacturers:

.

Proof. , therefore

;

Since , therefore , hence , that is, . □

Corollary 2. In terms of enthusiasm for traceability information sharing, retailers perform significantly better under the centralized decision-making model than under the decentralized one. For instance, the prefabricated food brand under Haidilao adopts a centralized decision-making model, in which retail stores actively share traceability information, such as consumer feedback, whereas production plants comprehensively share product traceability information. By analyzing consumer preference data, the production plants promptly adjust product flavors and packaging, launching prefabricated food products that better meet market demand. As a result, sales have increased substantially and brand goodwill has improved, providing strong evidence that the centralized decision-making model enhances retailers’ enthusiasm for traceability information sharing.

Compared with the decentralized model, the cost-sharing contract injects stronger motivation into traceability information sharing. This is because the subsidy reduces the sharing cost of the subsidized party, thereby increasing its marginal benefits from information sharing. From the perspective of profit maximization, the subsidized party becomes more willing to increase its investment in information sharing. For example, in the cooperation between Yonghui Superstores and Synear Food, Yonghui provided subsidies for the cost of online traceability information sharing. In response, Synear Food increased its online traceability efforts by providing detailed information on raw material origins, processing procedures, and quality inspection reports. Consumers could obtain comprehensive product details by scanning QR codes, which enhanced their confidence in product quality. Consequently, online sales increased significantly, driving higher brand recognition and offline sales, thereby fully validating the positive effect of this model on the manufacturer’s enthusiasm for online traceability information sharing.

Lemma 3. Offline traceability information-sharing behavior of prefabricated food manufacturers: Proof. , hence

;

Since

, therefore

, hence

, that is,

.

Therefore, if , then ; since the subsidy implicitly contains as discussed earlier, thus . □

Corollary 3. According to Proposition 2, the intensity of the manufacturer’s offline traceability information-sharing behavior under the centralized decision-making scenario is greater than that under the decentralized decision-making scenario. For example, in large-scale chain prefabricated food enterprises, the headquarters centrally allocates resources, encouraging each production base to actively collect and share traceability information across all offline channel stages—from production to sales terminals. Detailed records of product environmental parameters during warehousing and logistics processes are maintained to ensure product quality and efficient supply chain operation.

Under the cost-sharing model, when the subsidy ratio is set at an appropriate level, when , the manufacturer-led cost-sharing model can more effectively stimulate all parties’ enthusiasm for traceability information sharing. Its level of enthusiasm exceeds that of the retailer-led model and of the decentralized decision-making model.

For instance, Guolian Aquatic Products, positioned as a high-end brand in the market, faces consumers who are particularly concerned about product traceability information. Under the manufacturer-led cost-sharing model, the manufacturer provides the retailer with a higher proportion of subsidies for traceability information-sharing costs while also increasing its own investment in offline traceability information sharing. From the raw material procurement stage, detailed records are kept regarding the fishing area and the time of seafood capture. During the processing stage, hygiene standards and processing parameters are meticulously documented, and in the warehousing and logistics stages, temperature and humidity data are precisely recorded. Through comprehensive and detailed offline traceability information sharing, consumers gain a clear understanding of the entire process from ocean to table, leading to high recognition of product quality. Consequently, product sales and profits have increased substantially.

By contrast, another prefabricated food brand in the same region that adopted a retailer-led cost-sharing model offered limited subsidies to manufacturers, resulting in lower investment in offline traceability information sharing. Consequently, consumers’ trust and purchase intentions toward their products were relatively weak, and their market performance was markedly inferior. This fully verifies that, when the subsidy ratio is appropriately designed, the manufacturer-led cost-sharing model outperforms the retailer-led model in stimulating manufacturers’ enthusiasm for offline traceability information sharing, and both are superior to the decentralized decision-making model.

Lemma 4. Traceability information-sharing behavior of prefabricated food retailers: Proof. ,

, therefore

;

As implied in the preceding section , thus .

Since it is implicitly included in the previous analysis that , it follows that . □

Corollary 4. For retailers, the retailer-led cost-sharing strategy and the decentralized decision-making model tend to reduce their enthusiasm for traceability information sharing. This is because information sharing requires additional investment but yields limited direct benefits, resulting in low motivation. For example, in a regional prefabricated food market, local retailers provided subsidies to manufacturers, leading manufacturers to increase their traceability information-sharing efforts. However, the retailers remained inactive in collecting and sharing consumer feedback and product acceptance information, which prevented manufacturers from optimizing their products.

Under the centralized decision-making model, retailers’ enthusiasm for traceability information sharing increases significantly and reaches the highest level. Conversely, under the manufacturer-led cost-sharing contract, retailers’ enthusiasm can improve under certain conditions but still remains lower than that under the centralized model. For instance, Anjoy Foods provides subsidies and a management platform for its partner retailers. Some retailers, incentivized by this mechanism, actively share feedback information—such as reporting packaging issues—which helps manufacturers improve products and also increases their own profits. However, due to the limitations of interest alignment and coordination mechanisms in this model, the extent of improvement in retailers’ enthusiasm remains limited and fails to reach the level observed under centralized decision-making.

6. Case Analysis

Based on the aforementioned model, MATLAB 2016 is used to simulate the change processes of the interests of individual members and the overall supply chain in the food supply chain under different scenarios. In line with the findings of References [

38,

39] and combined with the actual situation of Anjoy Foods, some parameters are set as shown in

Table 5.

According to the studies by Hong & Huang (2016) and Xu et al. (2016), the following is assumed:

[

38,

39].

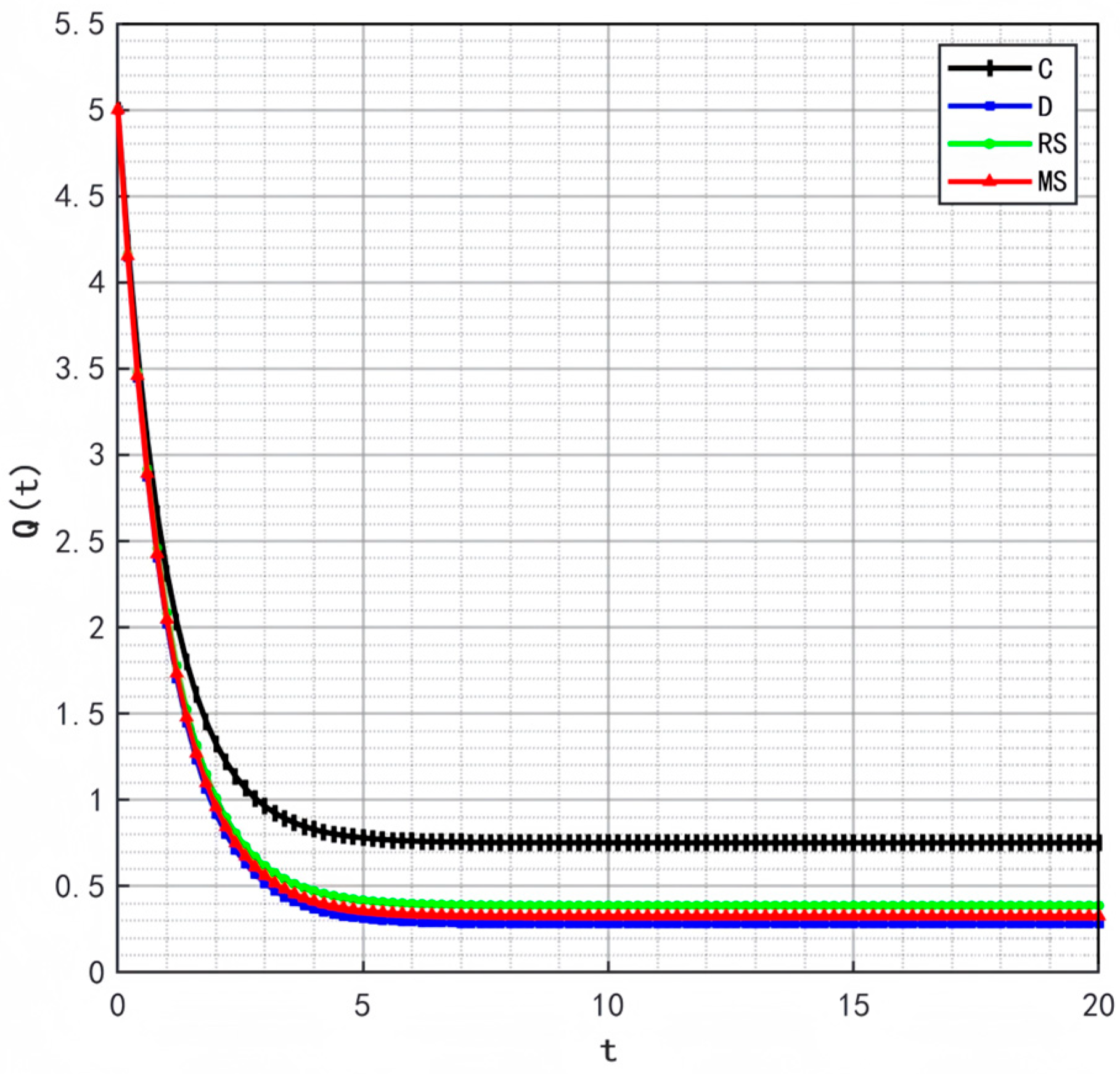

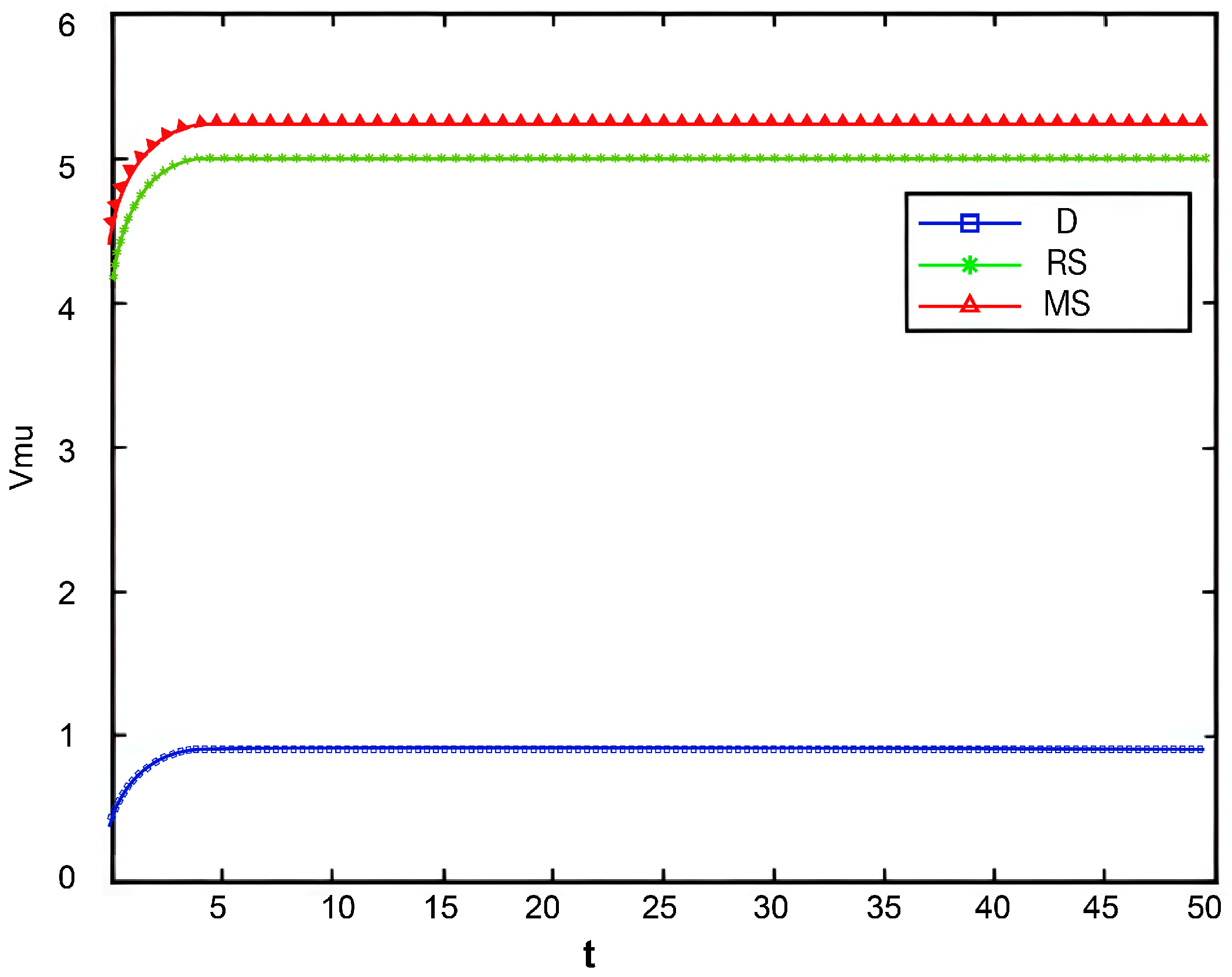

- (1)

Optimal Trajectories of Quality and Goodwill under Different Initial Values of

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 illustrate the optimal trajectories of product quality when the initial quality levels are

,

, and

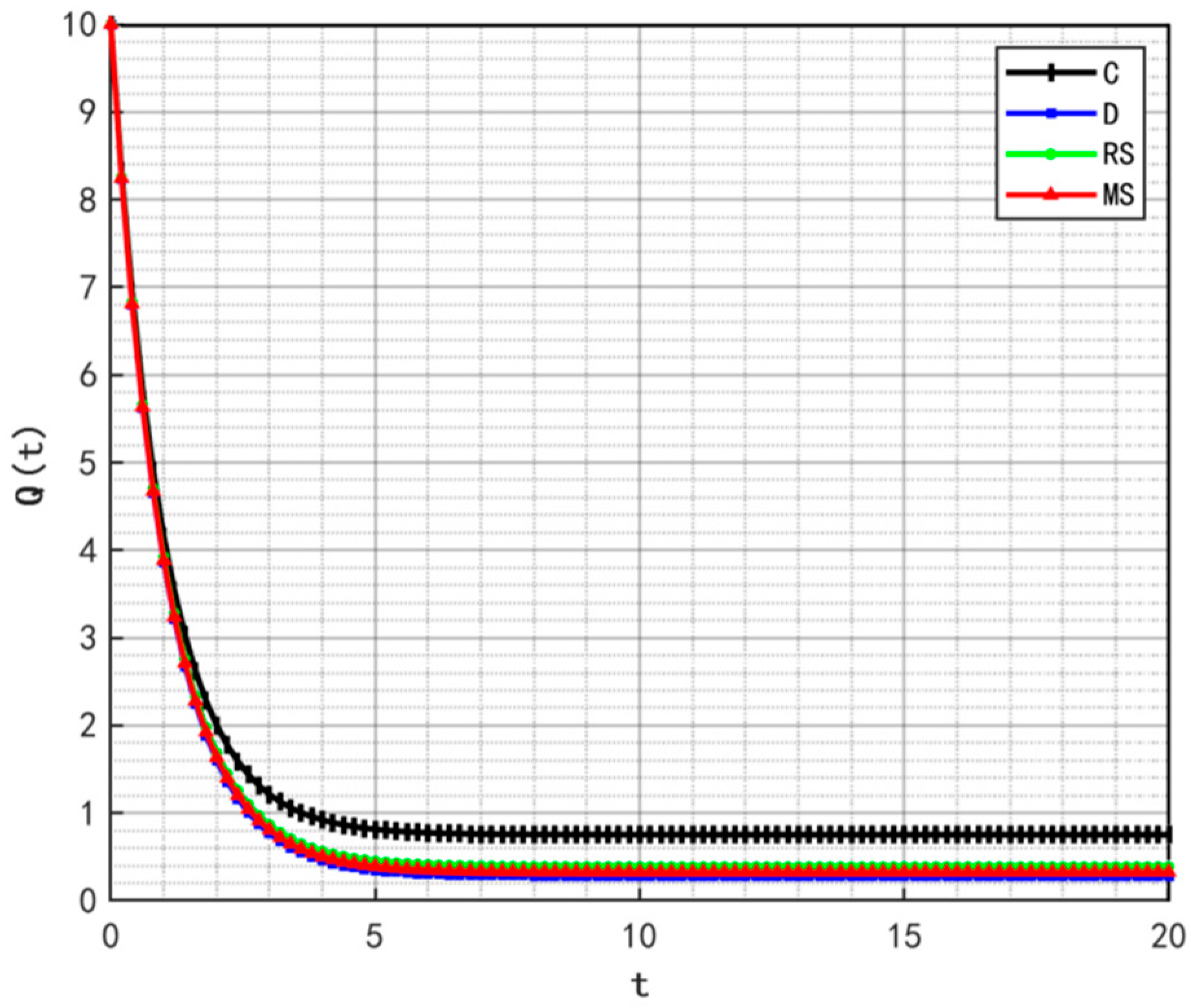

, respectively. Under all scenarios, the quality values eventually converge to a steady state. Similarly,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show the optimal trajectories of goodwill when the initial goodwill levels are

,

, and

, respectively. Likewise, in all cases, the goodwill values ultimately approach a stable equilibrium state.

The following conditions are satisfied:

- ➀

Centralized decision-making: , ;

- ➁

Decentralized decision-making: , ;

- ➂

Retailer-led cost-sharing model: , ;

- ➃

Manufacturer-led cost-sharing model: ,

The optimal trajectories of quality and goodwill in the prefabricated food supply chain exhibit an upward trend. By contrast, when these conditions are not met, both variables show a declining trend until they reach a steady state. This result is consistent with Lemma 1 in the comparative analysis section above, further verifying the validity of the previous conclusions.

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 show that the trajectories of quality and goodwill growth under the centralized decision-making scenario consistently outperform those in other scenarios, regardless of the initial levels of quality or goodwill. When the initial quality or goodwill is relatively low, the centralized decision-making model enables rapid improvement through coordination and collaboration among various stages of the supply chain, demonstrating its strong advantages in information sharing and resource integration.

Conversely, under the decentralized decision-making and cost-sharing contract scenarios (retailer-led and manufacturer-led), the growth of quality and goodwill is noticeably slower and tends to reach a steady state more quickly. This reflects the hindering effect of information asymmetry and conflicts of interest among supply chain members on goodwill accumulation in these settings. Although the cost-sharing contracts attempt to encourage information sharing through subsidies, the subsidizing party’s own information-sharing behavior does not improve significantly. As a result, the growth patterns of quality and goodwill are similar to those under decentralized decision-making. These findings indicate that a subsidy-based mechanism alone has inherent limitations in enhancing the overall quality and goodwill performance of the supply chain.

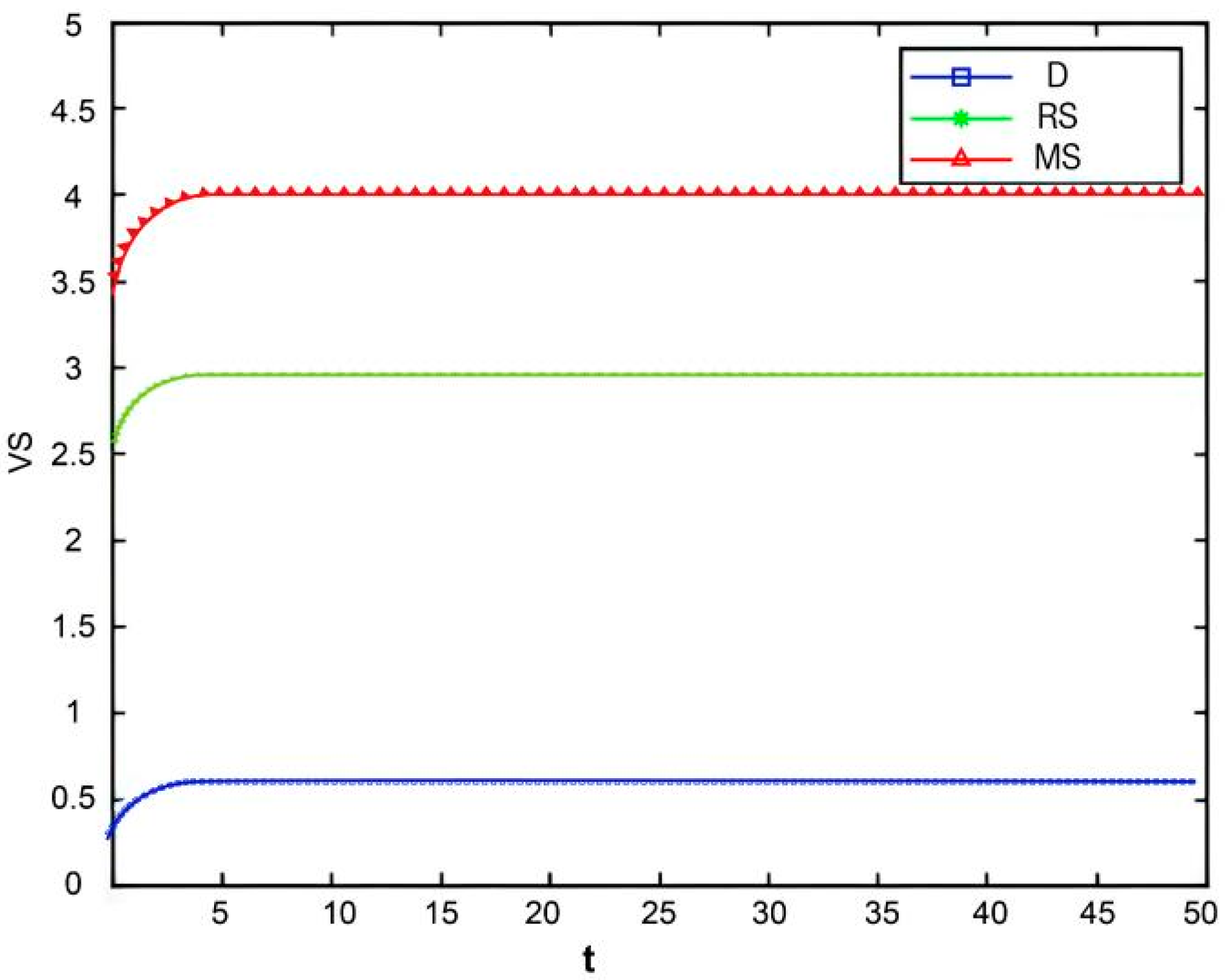

- (2)

Variation Trends of quality and goodwill with profit.

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 show that goodwill

significantly affects the profit of prefabricated food compared with product quality

. The main reason behind this phenomenon may lie in the high information barriers associated with quality evaluation for prefabricated food. On the one hand, consumers find it difficult to directly verify product quality; on the other hand, the increasing prevalence of falsified ingredient labels in the prefabricated food market further complicates consumers’ ability to distinguish between high- and low-quality products.

In such a market environment characterized by information asymmetry, a brand’s strong goodwill has become an important proxy indicator of product quality for most consumers. Consumers tend to equate prefabricated foods with good reputations and with high-quality products that are positively endorsed by word of mouth, thereby showing a stronger preference for purchasing products with higher goodwill.

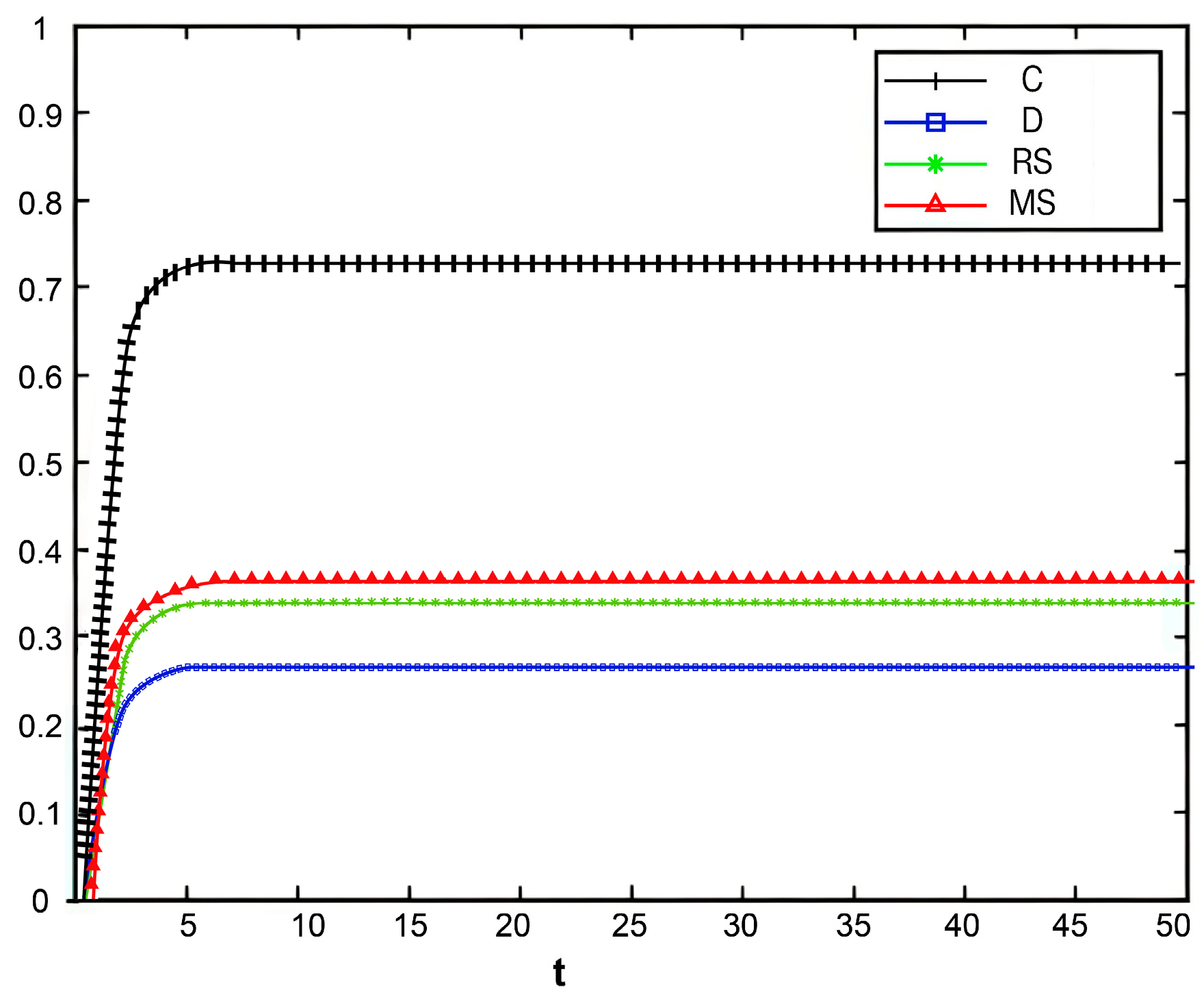

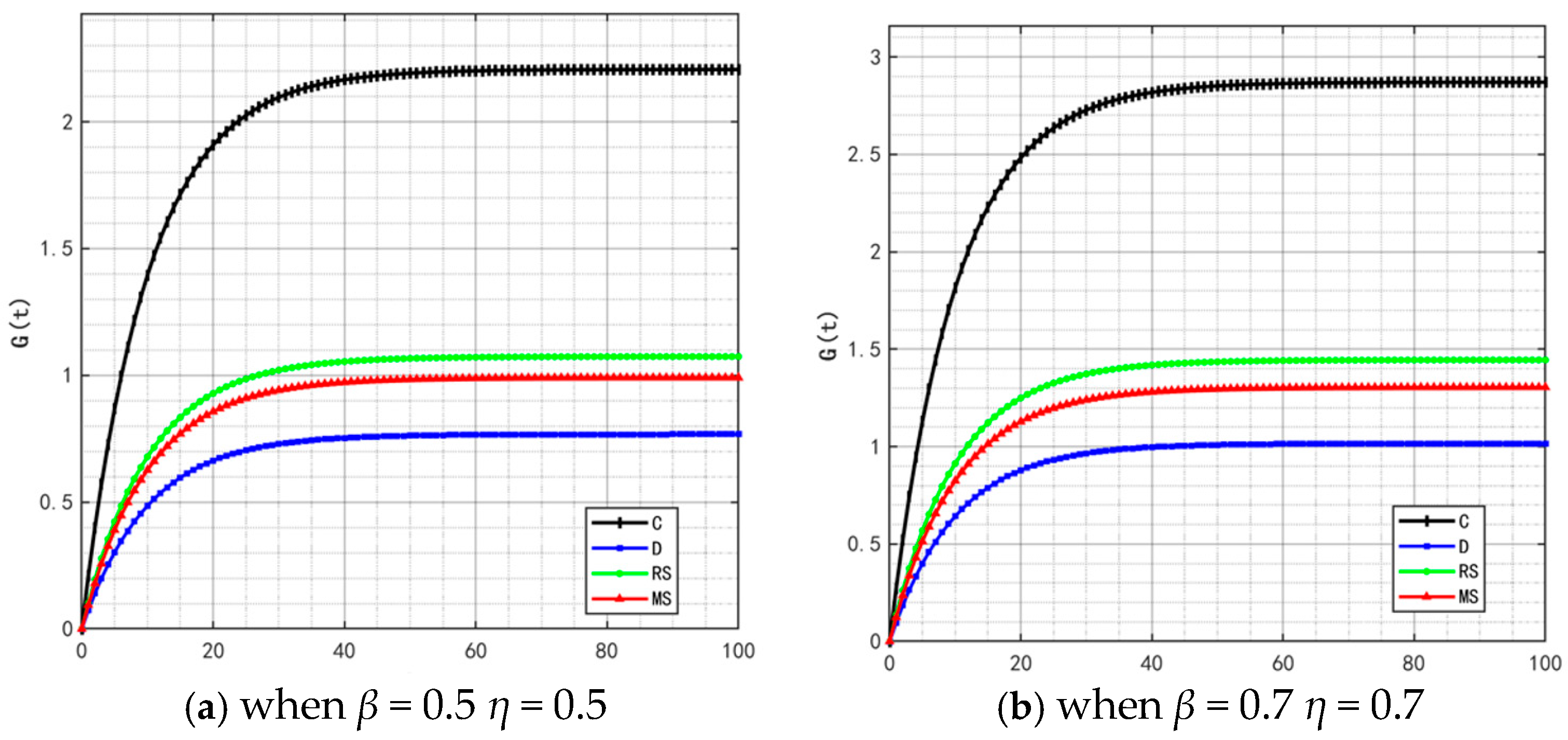

- (3)

Variation in market share over time under different decision-making scenarios.

Figure 11 illustrates the changes in market share of the prefabricated food supply chain over time under four scenarios: centralized decision-making, decentralized decision-making, retailer-led cost-sharing contract, and manufacturer-led cost-sharing contract.

Under the centralized decision-making scenario, the supply chain exhibits significant synergy, with high enthusiasm for information sharing. As a result, product quality and goodwill continuously improve, driving a steady increase in market share. Conversely, under the decentralized decision-making scenario, information asymmetry and conflicts of interest are more pronounced, leading to lower enthusiasm for traceability information sharing and limited coordination and efficiency within the supply chain. The Figure shows that compared with centralized decision-making, the growth of market share under decentralized decision-making is notably slower.

Further analysis of the retailer-led cost-sharing contract scenario in

Figure 11 shows that the manufacturer’s market share increases faster than in the decentralized model. This indicates that the subsidies provided by retailers effectively reduce manufacturers’ costs, enhance their enthusiasm for traceability information sharing, and thus promote market share growth. In the manufacturer-led cost-sharing contract scenario, the retailer’s market share also grows faster than when under decentralized decision-making, but still fails to reach the level achieved under centralized decision-making.

Overall, different decision-making scenarios significantly affect the market share of supply chain members. The centralized decision-making model achieves overall optimization of the supply chain through collaborative cooperation, making it the most effective approach for improving market share. Although the cost-sharing contract models partially mitigate the shortcomings of decentralized decision-making, further optimization of subsidy strategies and market mechanisms is needed to better promote information sharing and the overall development of the supply chain.

Variation in profit over time.

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15, respectively, illustrate the changes in profits of the manufacturer’s online and offline channels, the total manufacturer profit, and the retailer profit over time.

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15 reveal that different decision-making models lead to significant differences in the profits of supply chain participants. Overall, the manufacturer-led cost-sharing contract model achieves a nearly Pareto-optimal outcome. Conversely, under the decentralized decision-making model, the absence of coordination mechanisms results in slower profit growth and the lowest profit levels among all participants.

Figure 16 illustrates the variation in the total supply chain profit over time. It can be seen from the Figure that the centralized decision-making model does not yield the maximum profit, a result that deviates from the conventional perception that centralized decision-making typically enables overall supply chain optimization. However, this finding is supported by practical cases—take Weizhixiang, a prefabricated food enterprise, as an example. In its early stage, the enterprise faced profit pressure after adopting a fully centralized decision-making model. The core cause lies in the disconnection between the unified management model and the regional attributes of prefabricated food consumption: the headquarters implemented unified production and distribution based on the taste preferences of the East China market, which failed to adapt to the differentiated demands of South China, North China, and other regions, resulting in supply–demand mismatch and inventory backlogs. Meanwhile, the unified channel policies and cold chain distribution standards struggled to meet the actual needs of regional terminals, and the inverted logistics costs in remote areas further eroded profits, ultimately undermining the enterprise’s overall profitability.

The centralized decision-making model is generally believed to achieve optimal resource allocation through collaborative cooperation in supply chain management, thereby maximizing the total supply chain profit. However, in this study, the centralized decision-making model did not achieve the highest profit, and the main reasons may be as follows:

Insufficient incentive mechanisms: Although centralized decision-making pursues overall profit maximization, it lacks explicit incentives for individual participants to share information, leading to low enthusiasm among manufacturers and retailers and reduced efficiency in information sharing.

High coordination costs: Centralized decision-making requires a high degree of coordination, which increases coordination costs and complicates decision-making processes. This may delay market responses and reduce the flexibility of the supply chain.

Unequal profit distribution: Profit distribution under centralized decision-making may be unbalanced. Manufacturers and retailers might experience reduced motivation if they bear excessive costs or receive insufficient returns.

- (4)

Relationship between manufacturers’ traceability information-sharing behavior and profit.

Figure 17 and

Figure 18 show that, compared with online traceability information-sharing behavior, the manufacturers’ offline traceability information-sharing behavior has a more pronounced effect on the profit of prefabricated food manufacturers. This is primarily because the offline channel directly interacts with end consumers. Once offline traceability information sharing enhances consumers’ trust in the product, it can quickly translate into purchasing behavior, directly influencing sales and profits. Conversely, although online channels allow for broader information dissemination, consumers may find it difficult to assess the authenticity of online information, and their purchasing decisions are more easily influenced by price and promotional factors. Therefore, offline traceability information sharing exerts a more direct and effective influence on consumers’ purchasing decisions.

Across different decision-making models, the effect of traceability information-sharing behavior on profits varies significantly. Under the centralized decision-making model, coordination among all parties allows the manufacturer’s information-sharing efforts to receive sufficient support. The manufacturer’s online information-sharing activities align effectively with retailer feedback, facilitating product optimization and profit growth. Under the decentralized decision-making model, however, manufacturers prioritize their own profit and may reduce investments in information sharing after weighing costs and benefits, thereby weakening product competitiveness and limiting profit growth.

- (5)

Optimal trajectories of product quality, goodwill, and profit under different parameter combinations.

The quality and safety of prepared foods are crucial to public health. In the event of concentrated exposure to negative public opinion, the government will introduce stricter production supervision measures. At this point, the traceability information-sharing behavior between food manufacturers’ online and offline channels becomes critical, which will promote the development of traceability information-sharing technology but also increase technical costs. Although some governments provide technical subsidies, continuous technological upgrading and the increase in implicit participants in the supply chain will still push up manufacturers’ technology application costs. Based on this, we set two groups of values for the coefficients (

,

) that measure the impact of traceability information sharing on product quality in manufacturers’ online and offline channels: (0.5, 0.5) and (0.7, 0.7). The optimal evolutionary trajectories of corresponding product quality and goodwill are shown in

Figure 19 and

Figure 20.

By comparing the simulation results in

Figure 2,

Figure 5,

Figure 19 and

Figure 20, it is clear that when the coefficients

and

(which measure the intensity of traceability information sharing’s impact on product quality) increase, only under the retailer-led cooperation model does product quality show a fluctuating trend of “rising from the bottom to the second place and then falling back to the bottom.” This variation rule also applies to the evolutionary process of product goodwill. Under the retailer-led model, the quality empowerment effect of channel information sharing exhibits “phased differences”: in the initial stage, the increase in

and

directly enhances manufacturers’ quality control capabilities, driving rapid improvement in product quality; however, as the degree of information sharing deepens, retailers’ channel dominance will gradually squeeze manufacturers’ quality investment space, while the marginal benefits of information sharing gradually diminish, ultimately leading to a decline in product quality and goodwill from high levels.

By comparing

Figure 12,

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16 and

Figure 21, it is found that as β and η (the coefficients of traceability information sharing’s impact on product quality) increase, the profit ranking order of each subject under different models remains unchanged, with only numerical increases. This is because the increase in β and η only enhances the positive impact of traceability information sharing on product quality, thereby generally amplifying the profit level of each subject, but does not change the interest distribution logic under different models.

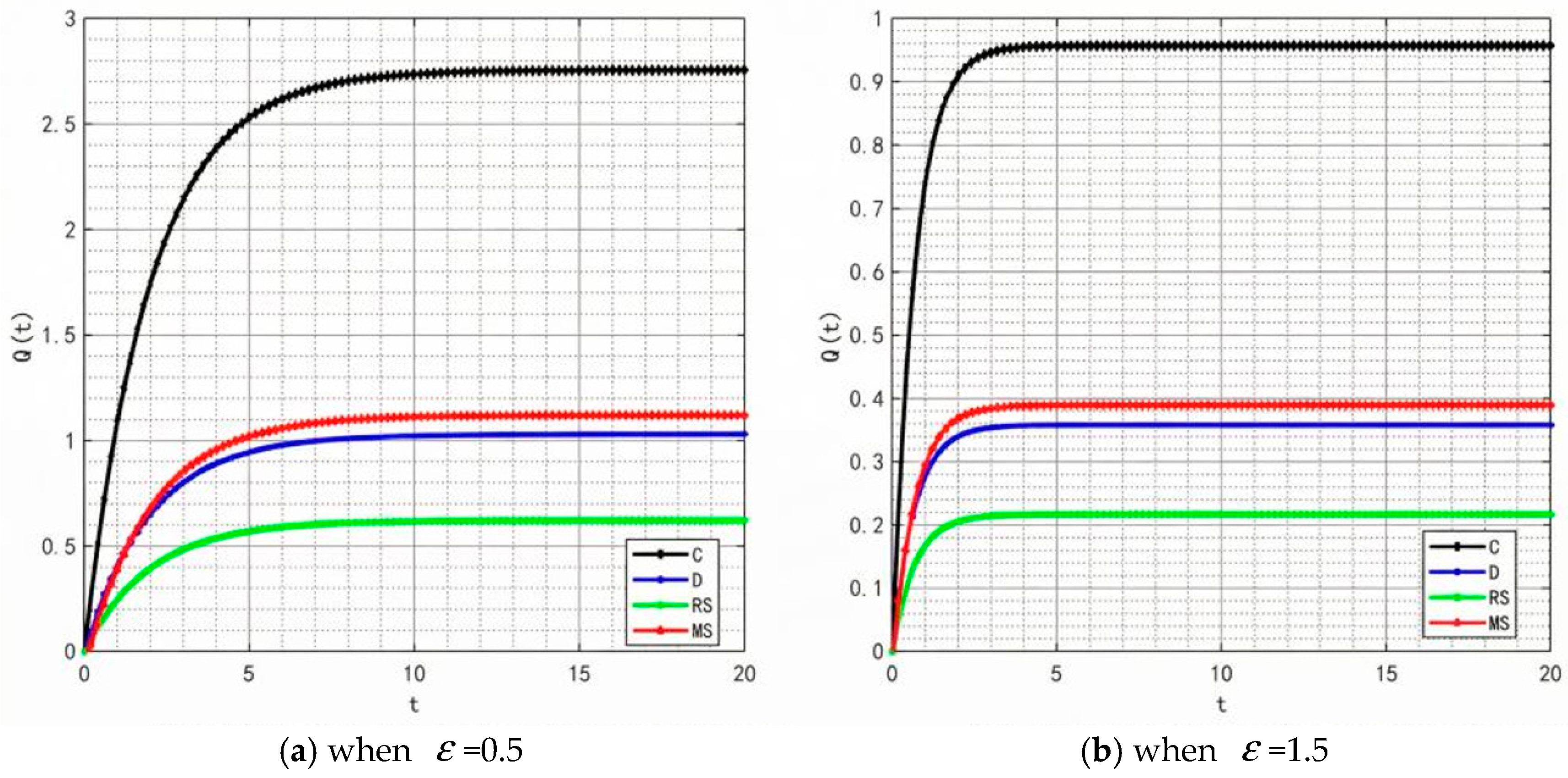

- (6)

Impact of changes in traceable food quality attenuation coefficient on product quality, goodwill, and profit.

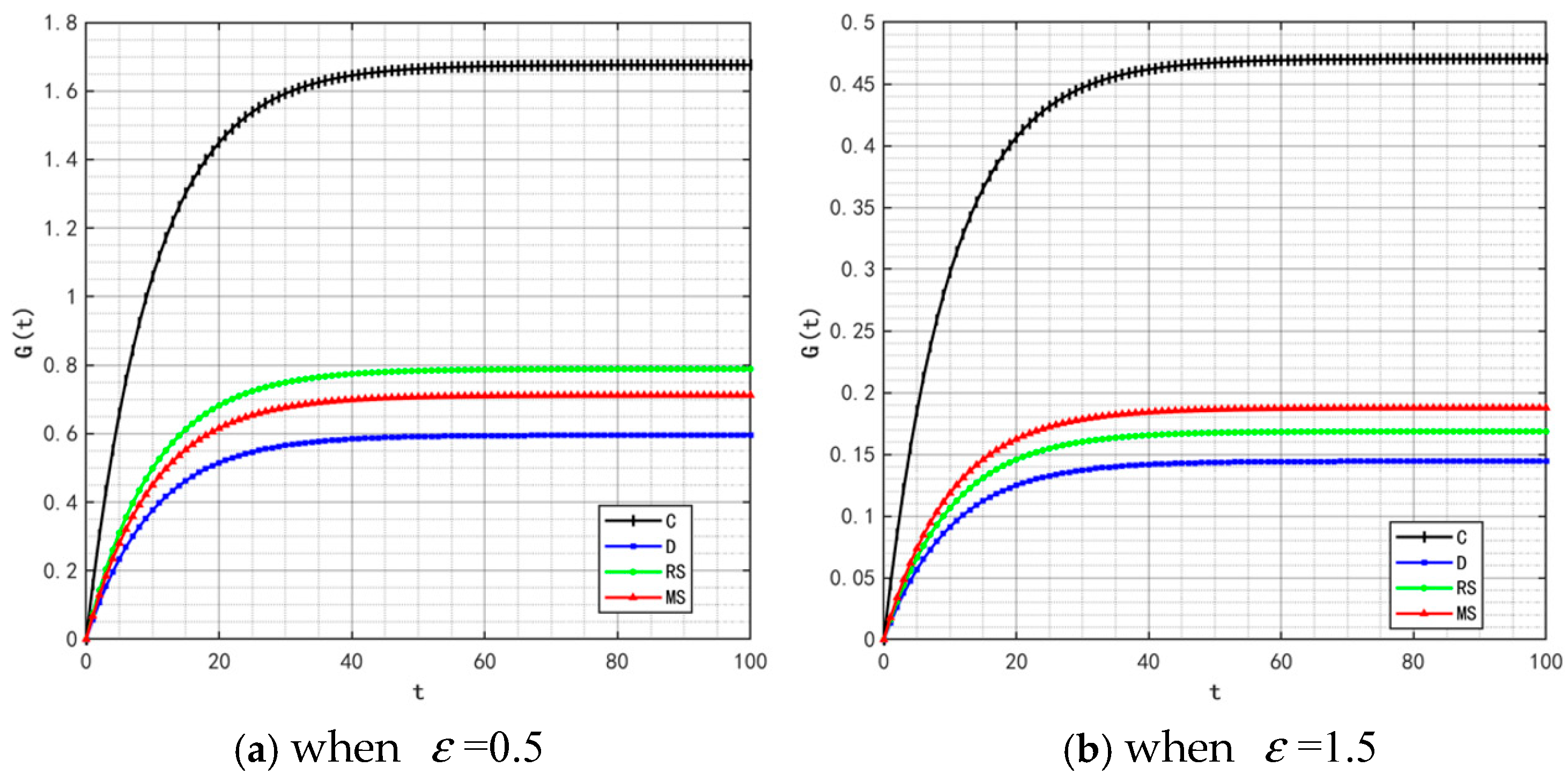

With the rise in market demand, some unscrupulous merchants will seek profits by tampering with traceability information—such as relabeling expired food as freshly produced or delaying the update of key data. In addition, the frequent appearance of professional terms in traceability information makes it difficult for ordinary consumers to understand. These factors will significantly affect the value of the traceable food quality attenuation coefficient

. Therefore,

is set to 0.5 and 1.5, and the corresponding changes in product quality and goodwill are shown in

Figure 22 and

Figure 23.

By comparing the simulation results in

Figure 2,

Figure 5,

Figure 22 and

Figure 23, it is clear that as the system’s attenuation coefficient

gradually increases, the evolutionary laws of product quality and goodwill under different cooperation models show significant differentiated characteristics. Among them, only under the retailer-led cooperation model does product quality exhibit a unique fluctuating trajectory—first rapidly rising from the initial bottom to the second place, then gradually falling back to the bottom. The dynamic change in product goodwill is more complex: the goodwill under the centralized model always maintains the optimal level, while the goodwill ranking of the manufacturer-led model experiences continuous fluctuations of “falling from the second place to the bottom, then rising back to the third place.” The root cause of this phenomenon lies in the differences in the interaction mechanism between the “attenuation effect” and “subject decision-making logic” under different models. For the retailer-led model, the initial increase in ε will force retailers to strengthen channel-side quality collaboration; however, as the attenuation effect intensifies, retailers’ short-term profit orientation will lead them to shift resources to channel traffic, weakening the empowerment of manufacturers’ quality investment, and ultimately resulting in a quality decline. The centralized model, relying on unified decision-making and scheduling capabilities, can offset the negative impact of the attenuation coefficient, thereby stably maintaining optimal goodwill. As for the manufacturer-led model, the initial increase in ε will weaken the long-term effectiveness of its quality investment, but in the later stage, manufacturers will passively increase goodwill repair investment to maintain market share, thereby promoting a slight recovery in their ranking.

By comparing

Figure 12,

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16 and

Figure 24, it is found that when the system’s attenuation coefficient

increases, the profit ranking order of each subject under different models remains unchanged, but the absolute profit values show differentiated fluctuations—the profit of manufacturers’ online channels shows an upward trend over time, while the profits of other subjects decrease. This is because the core function of the system attenuation coefficient

is to measure the time-sensitive loss intensity of factors such as traceability information and quality spillover. An increase in ε will accelerate the value attenuation of cross-channel factors relied on by most subjects. However, the interest distribution mechanism of different models is determined by the cooperation rules of the models and is not directly affected by factor attenuation, so the relative profit ranking under each model remains stable. The profit logic of manufacturers’ online channels relies more on real-time information flow; although the increase in ε accelerates the attenuation of traditional factors, it also forces the channel to strengthen real-time information-sharing efficiency, enabling it to more accurately capture short-term market demand and reduce information asymmetry costs, ultimately offsetting the negative impact of attenuation and achieving profit growth. In contrast, other subjects such as offline channels and retailers, rely more on long-term factor accumulation and are unable to quickly adapt to the value loss caused by attenuation, leading to a natural decrease in profits.

- (7)

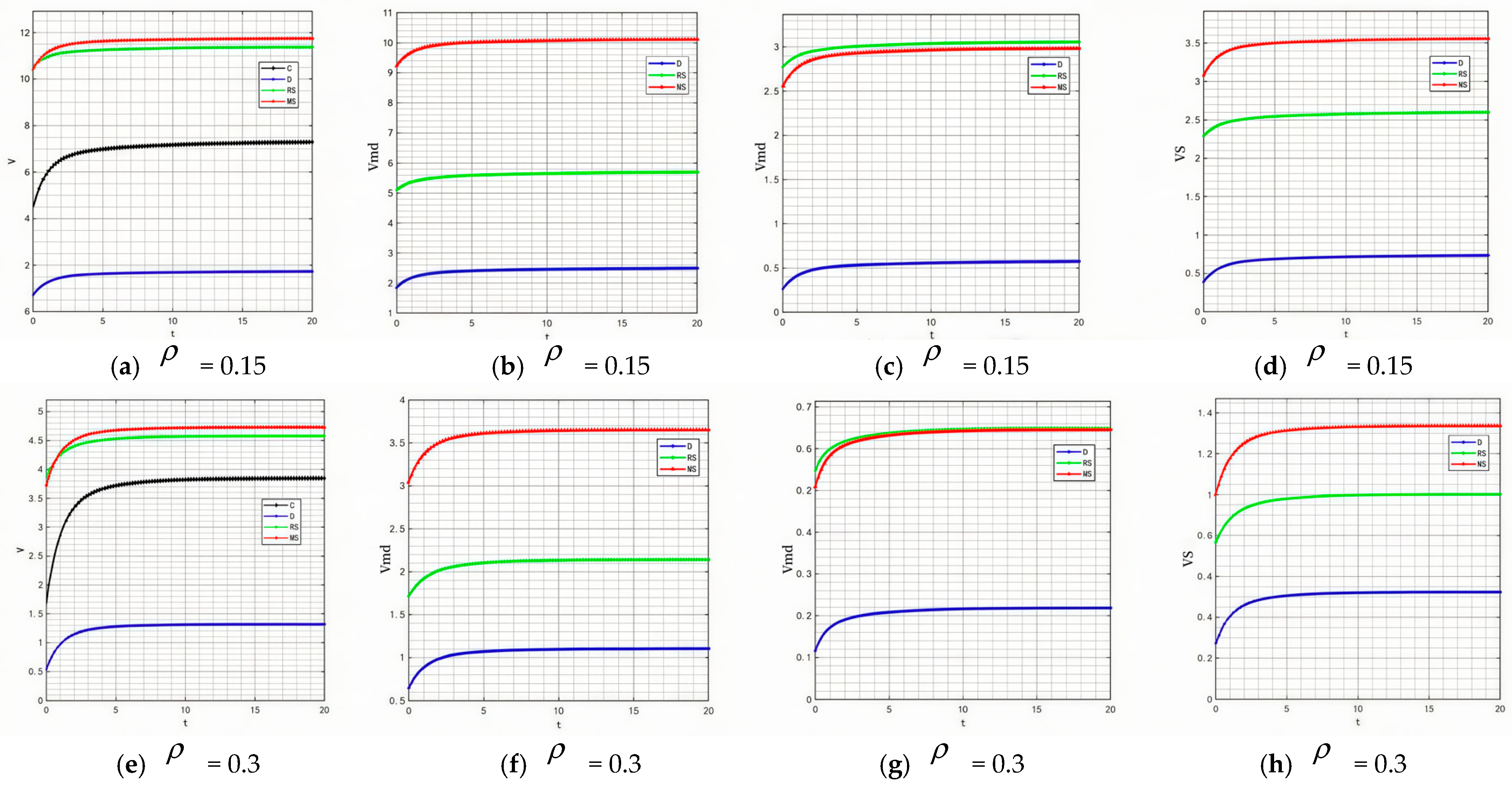

Impact of changes in discount rate on product quality, goodwill, and profit.

Market risk is a key variable affecting the discount rate

, and this correlation is particularly significant in the food industry. When the food industry faces risks such as supply chain instability (e.g., sharp fluctuations in raw material prices, logistics disruptions, and insufficient production capacity in key links), policy and regulatory adjustments (e.g., upgrades to food safety standards, stricter environmental protection requirements, and changes in import and export restrictions), or sudden changes in consumer demand, the discount rate

tends to show an upward trend. Therefore,

is set to 0.15 and 0.3, and the results are shown in

Figure 25 and

Figure 26.

By comparing the simulation results in

Figure 2,

Figure 5,

Figure 25 and

Figure 26, it can be clearly observed that as the discount rate

gradually rises, the evolution of product quality shows obvious model heterogeneity—under the manufacturer-led cooperation model, its quality ranking continuously drops from the initial second place to the bottom, and the absolute quality value also decreases simultaneously. This change logic also holds in the product goodwill dimension, but there are significant differences in numerical trends: the goodwill ranking of the manufacturer-led model also falls from the second place to the bottom, but its absolute goodwill value shows a gradual upward trend.

The root cause of this phenomenon lies in the “two-way mechanism” of the discount rate increase on the decision-making of food industry subjects: from the product quality dimension, a higher discount rate means manufacturers assign lower weights to long-term returns. Improvements in food quality rely on long-cycle investments, such as raw material control and process upgrades, and the discounted present value of future returns from such investments will shrink as the discount rate rises. Therefore, manufacturers will take the initiative to reduce quality investment, directly leading to a simultaneous decline in quality ranking and numerical value. From the product goodwill dimension, although the increase in the discount rate also weakens manufacturers’ emphasis on long-term goodwill accumulation, goodwill in the food industry is directly linked to market trust. To avoid consumer loss caused by quality decline, manufacturers will switch to short-term, effective goodwill maintenance methods. The costs of such investments can be covered by current returns, and the effects can be quickly reflected in goodwill statistics, thus forming a differentiated performance of falling rankings but rising numerical values.

By comparing

Figure 12,

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16 and

Figure 27, it is found that when the discount rate

increases, the profit ranking order of each subject under different models remains unchanged, and only the absolute profit values show a downward trend. This is because the discount rate reflects the time value discount of future returns by subjects—the higher ρ is, the lower the weight of future returns in current profit accounting. The relative profit ranking of supply chain models is determined by their cooperation mechanisms and is not directly affected by the logic of time value discount, so the relative strength of profits under different models remains stable. At the same time, each subject’s profit includes a certain proportion of expected future returns (e.g., quality premiums from long-term cooperation and subsequent returns from channel collaboration). The increase in ρ will amplify the discount rate of these future returns, leading to a general decrease in the absolute current profit values of all subjects. However, this discount is a “same-logic weakening” of profits under all models and does not change the inherent interest distribution characteristics of different models, so the relative profit ranking remains unchanged.

7. Conclusions and Limitations

- (1)

Conclusions

This paper builds a two-level supply chain model of prefabricated food, which covers manufacturers and retailers, integrates an online and offline two-channel sales model, and systematically explores the coordination mechanism and profit distribution of traceability information-sharing behavior. By constructing a game model in the context of centralized decision-making, decentralized decision-making, and two kinds of cost-sharing contracts, the equilibrium results of different decision-making models are compared and analyzed, and the research conclusions are verified by an example analysis. The following research results are formed: (1) The centralized decision-making model is the best choice to improve the market share of the prefabricated food supply chain. Although the cost-sharing contract model can improve the growth rate of market share, there is still a gap between the centralized decision-making model and the cost-sharing contract model. (2) What is different from the traditional cognition is that the centralized decision-making model is not the model with the largest profit, but the cost-sharing decision led by the manufacturer has basically achieved Pareto optimality, among which the most important reasons may be the insufficient incentive mechanism of the centralized decision-making model, the high coordination cost, and the uneven distribution of benefits. (3) Manufacturer’s offline channel traceability information-sharing behavior has a more severe impact on profit than online channels. (4) In the market environment of asymmetric information, consumers have difficulty directly judging the quality of pre-made food, so the impact of goodwill on profit is more prominent. (5) When the coefficient measuring the intensity of traceability information sharing’s impact on product quality across manufacturers’ online and offline channels increases, only under the retailer-led cooperation model do product quality and goodwill exhibit a fluctuating trend of “rising from the bottom to the second place and then falling back to the bottom,” while the profits of all subjects increase simultaneously. (6) As the system attenuation coefficient increases, the evolution of product quality and goodwill under different cooperation models shows significant differences: under the retailer-led model, quality fluctuates in the trajectory of “bottom → second place → bottom”; under the manufacturer-led model, goodwill fluctuates as “second place → bottom → third place”; and the goodwill under the centralized model remains optimal at all times. In terms of profits, the profits of manufacturers’ online channels increase over time, while those of other subjects decrease. (7) When the discount rate rises, the manufacturer-led model presents distinct characteristics: both the ranking and absolute value of product quality decline synchronously, the ranking of goodwill falls, but its absolute value rises against the trend, the evolution of product quality and goodwill shows obvious model heterogeneity, and the profits of all subjects generally decrease.

- (2)

Management Inspiration

To sum this up, the high-quality development of the prefabricated food supply chain needs to build a win–win ecosystem with traceability information sharing as the core link and fair distribution as the collaborative basis.

The sharing of traceability information is the key to strengthening the product quality defense line and enhancing the trust of consumers. The core enterprise needs to play a leading role. On the one hand, each entity should actively enhance the power of online and offline channel traceability information-sharing on product quality, opening up the whole channel traceability data link, and strengthening the guiding role of traceability information on production, processing, and quality control. This not only simultaneously enhances the product quality and brand reputation under each cooperation mode, but also realizes the general growth of profit of each entity in the supply chain. It is the core of leveraging the positive cycle of “quality–goodwill–profit”. On the other hand, through the cost-sharing contract, the initiative of upstream and downstream is mobilized, a differentiated allocation proportion is set according to contribution degree, and periodic incentives such as “initial advance + later profit return” are supplemented to break down the information barrier.

The government can also introduce targeted subsidy policies to lower the coordination threshold. Provide 20–30% subsidy for sourcing equipment procurement of small- and medium-sized suppliers and a one-time start-up capital subsidy for cross-link information platform construction led by core enterprises. At the same time, based on the Shapley value method, the profit distribution can be quantified according to the marginal contribution of each entity to the alliance, the quality risk cost can be bound with the incremental revenue, and transparent accounting can be realized by means of a third-party platform, so as to balance the multi-interests of core enterprises, suppliers, processors, distributors, and the like, and avoid weakening the cooperative power due to the imbalance of cost or revenue.

The enterprise also needs to establish a flexible cooperation model adaptation mechanism: considering that the comprehensive performance of “quality–goodwill–profit” of different cooperation models is significantly differentiated from environmental variables such as quality attenuation coefficient and industry discount rate change; flexible switching rules between models should be established (for example, the cooperation model should be dynamically adjusted based on the critical threshold of attenuation coefficient and discount rate), and meanwhile, information and resources interfaces between different models should be opened up, so as to eliminate the connection barriers of model switching and avoid the efficiency loss caused by operation faults.

In addition, enterprises need to combine the transparency of traceability information with the construction of brand goodwill in-depth, accumulate brand assets by virtue of the high-quality image of traceability, and enhance market competitiveness; at the industry level, government and enterprise should work together to speed up the establishment of a unified traceability platform, formulate standardized information standards, and address the root causes of information asymmetry; the regulatory authorities need to strengthen the whole chain of quality supervision to protect the rights and interests of consumers, and to ultimately promote the industry to move from decentralized competition to win–win cooperation and achieve standardized and high-quality development.

- (3)

Inadequacy

Although this research has formed corresponding research results in the aspects of model construction and analysis, there is still room for optimization. First, due to the convenience of solving the model, the research assumes that the supply chain members have complete information, and the case analysis relies on hypothetical parameters. This setting limits the practical application scope of the model to a certain extent. Secondly, the current research focuses on the category of secondary supply chains, and the follow-up can extend the exploration to more complex multi-level supply chain situations or include more participants, such as logistics providers and e-commerce platforms, so as to more comprehensively analyze the issue of traceability information sharing in prefabricated food supply chains. Thirdly, due to the complexity of the solving process of differential games, this study only constructs a two-level supply chain analysis framework composed of manufacturers and retailers, and does not include the key constraints commonly found in realistic scenarios, such as asymmetric information, limited rationality of decision makers, lack of trust among cooperating agents, etc. Subsequent research can further enrich the hypothetical dimensions of the model, and by introducing elements such as multi-level supply chain structure, dynamic information interaction mechanism, and limited rational decision-making criteria, an analysis paradigm that is closer to the real market environment can be constructed.