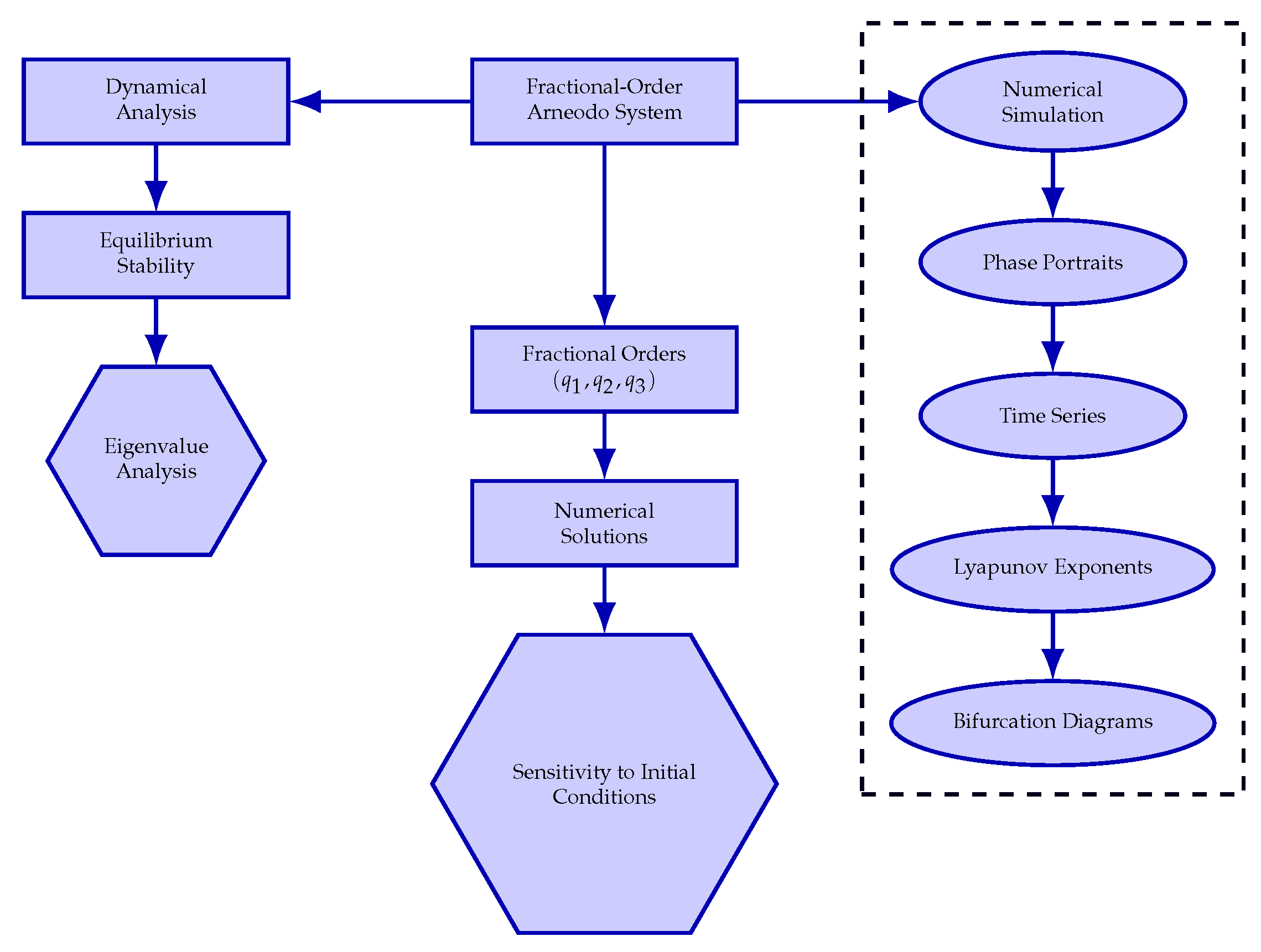

Exploring Stability and Chaos in the Fractional-Order Arneodo System via Grünwald–Letnikov Scheme

Abstract

1. Introduction

- In this presentation, we will provide the theoretical explanation of these transitions using a stability analysis supported by Jacobian eigenvalues.

- These results demonstrate that the fractional order q represents an effective control parameter for adjusting nonlinear behavior, making available potential paths towards applications of secure communication, random number generation, and hardware implementation with FPGA platforms.

2. Fractional-Order Dynamical Analysis

2.1. Jacobian Matrix

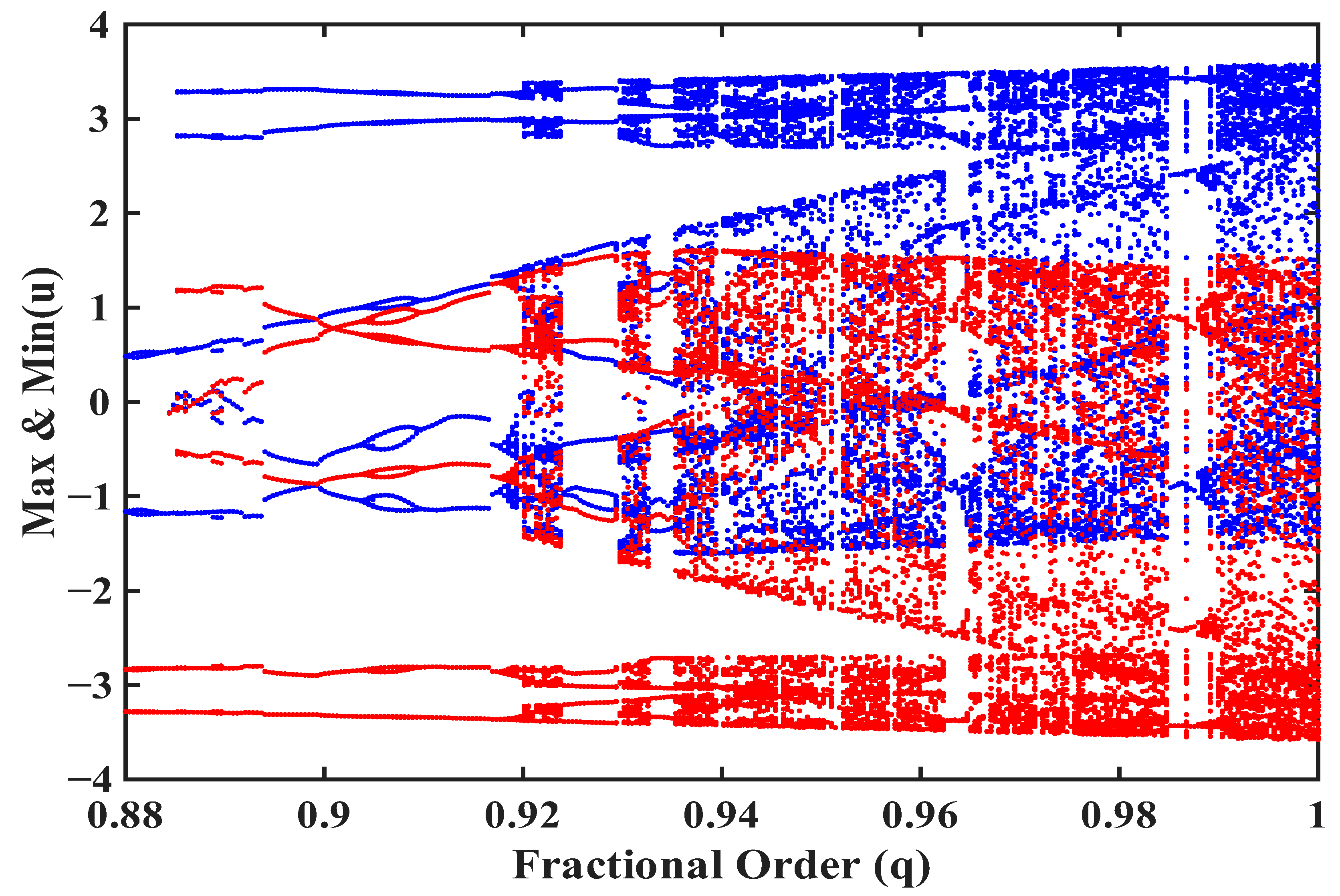

2.2. Local Stability of Equilibria

- (a)

- Classical case

- (b)

- Fractional order

- (c)

- Incommensurate fractional orders

2.3. Divergence of the Fractional-Order Arneodo System

3. Grünwald–Letnikov Numerical Method

4. Numerical Solutions

5. Dynamical Analysis

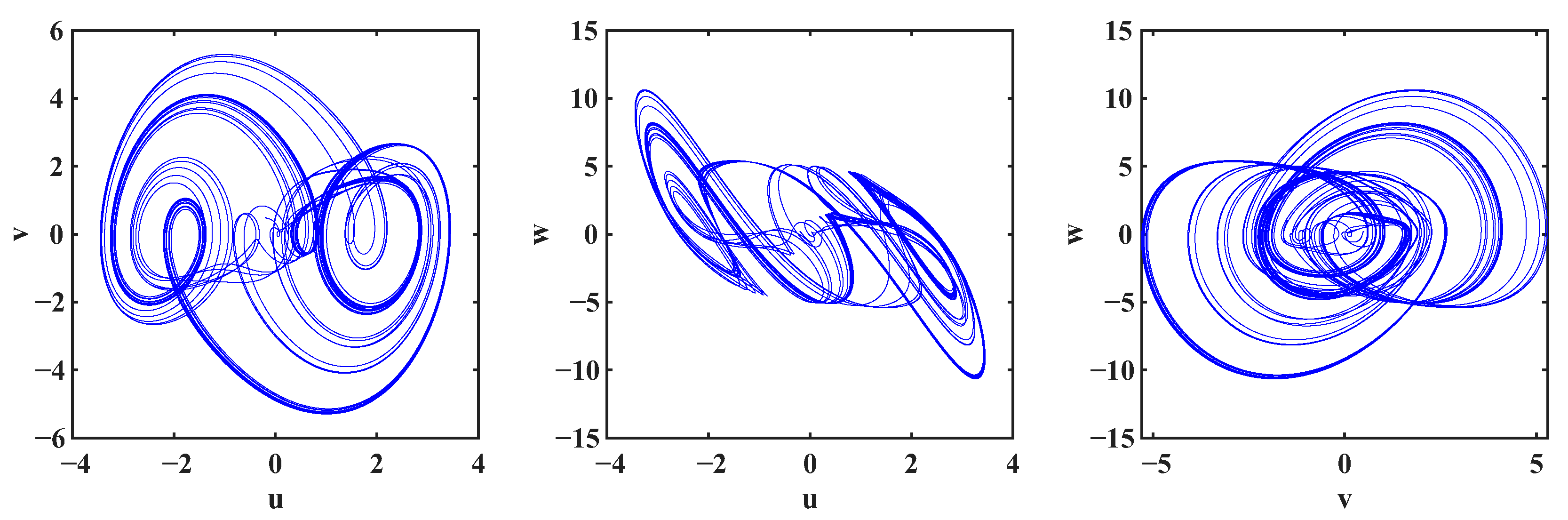

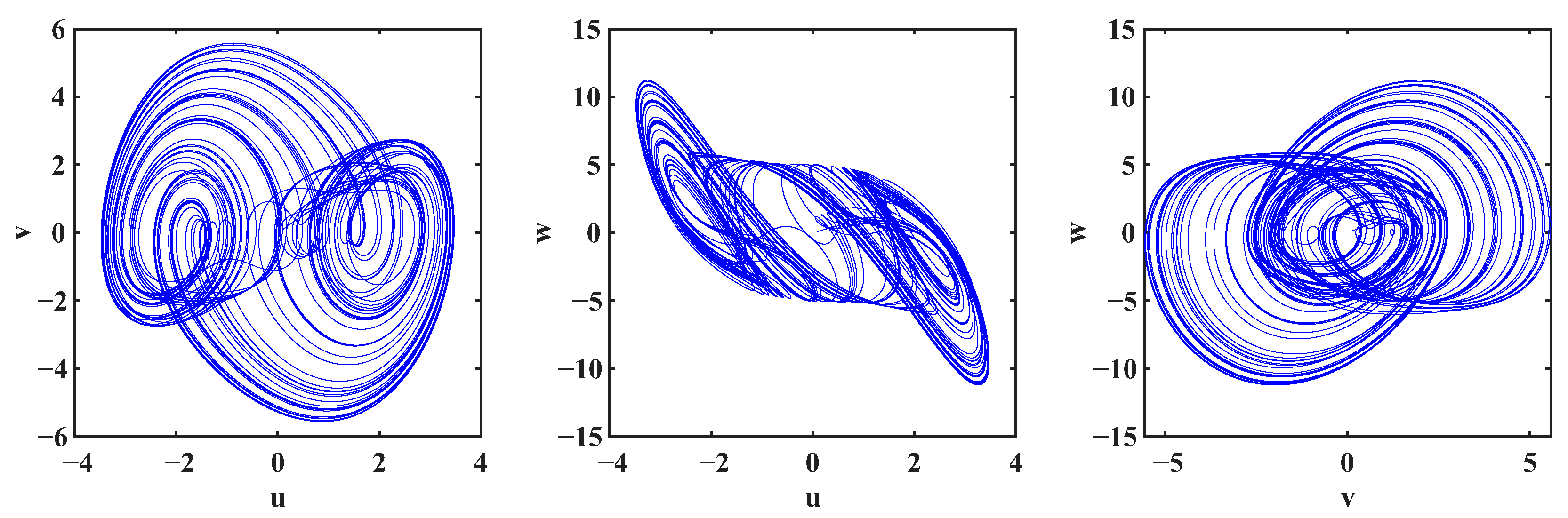

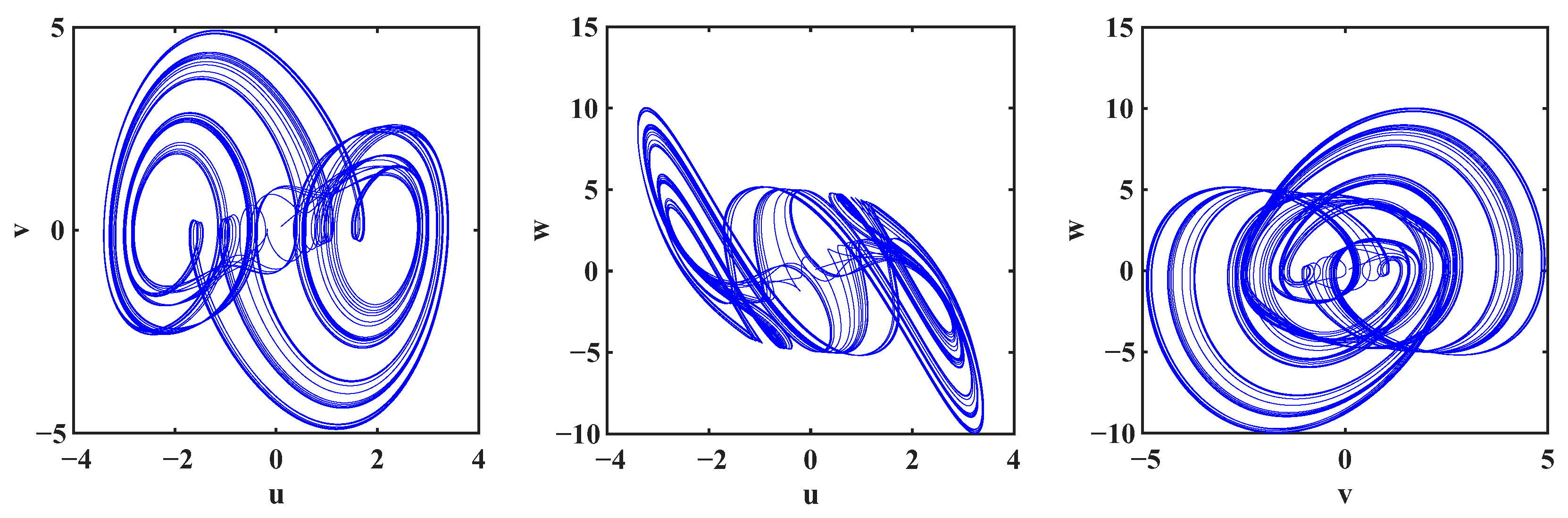

5.1. Choas Behavior

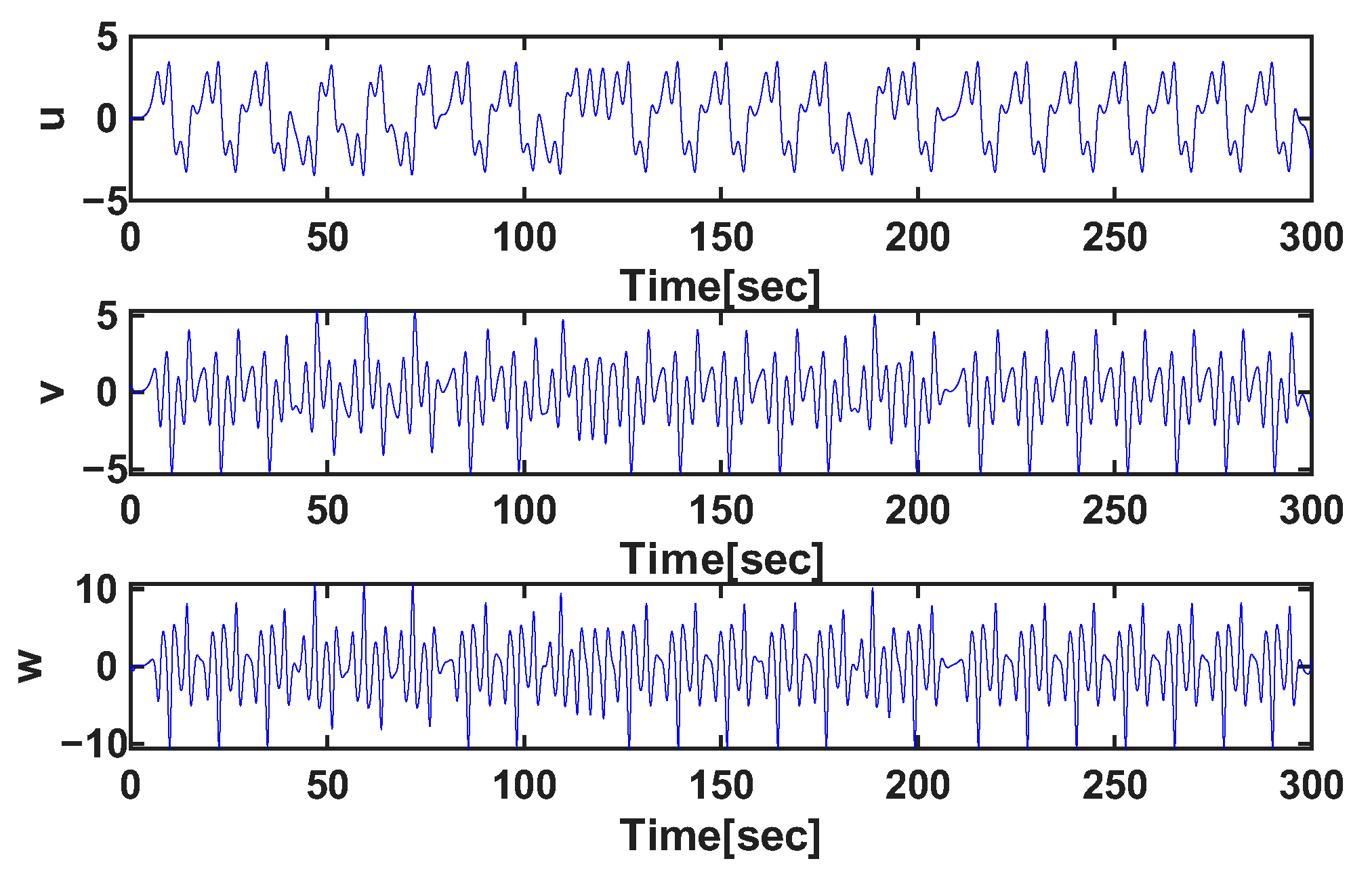

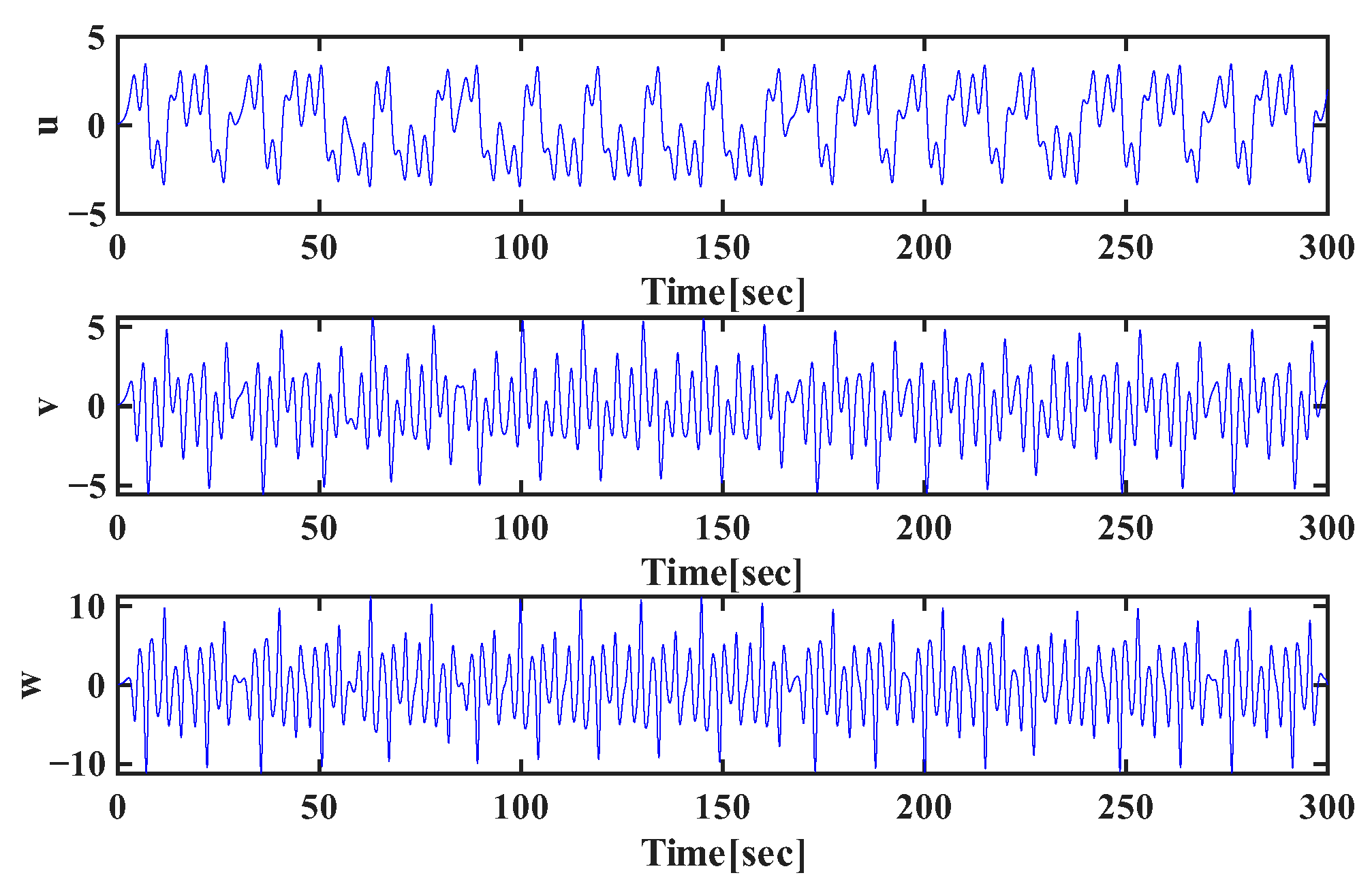

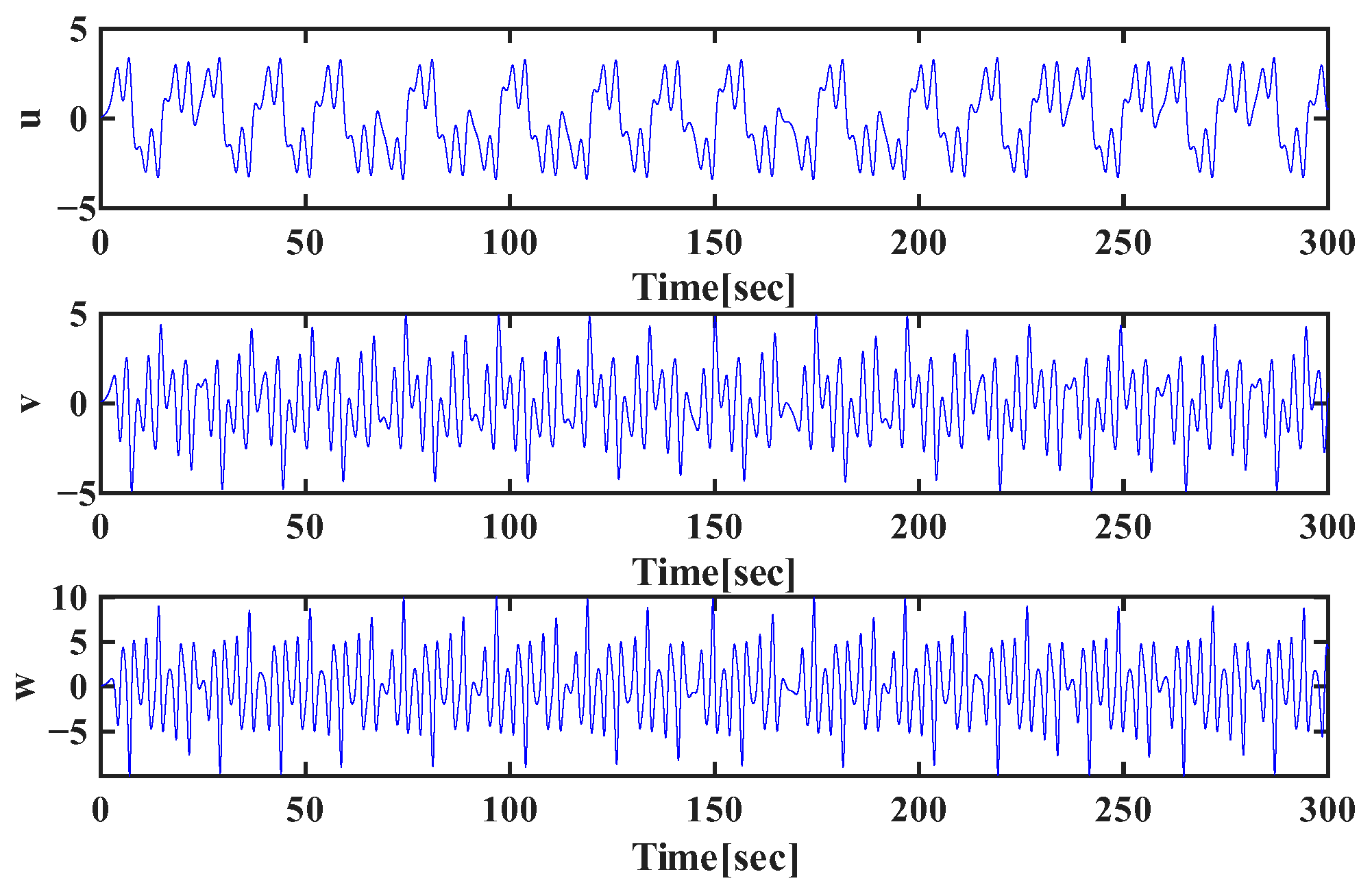

5.2. Time-Series Dynamics

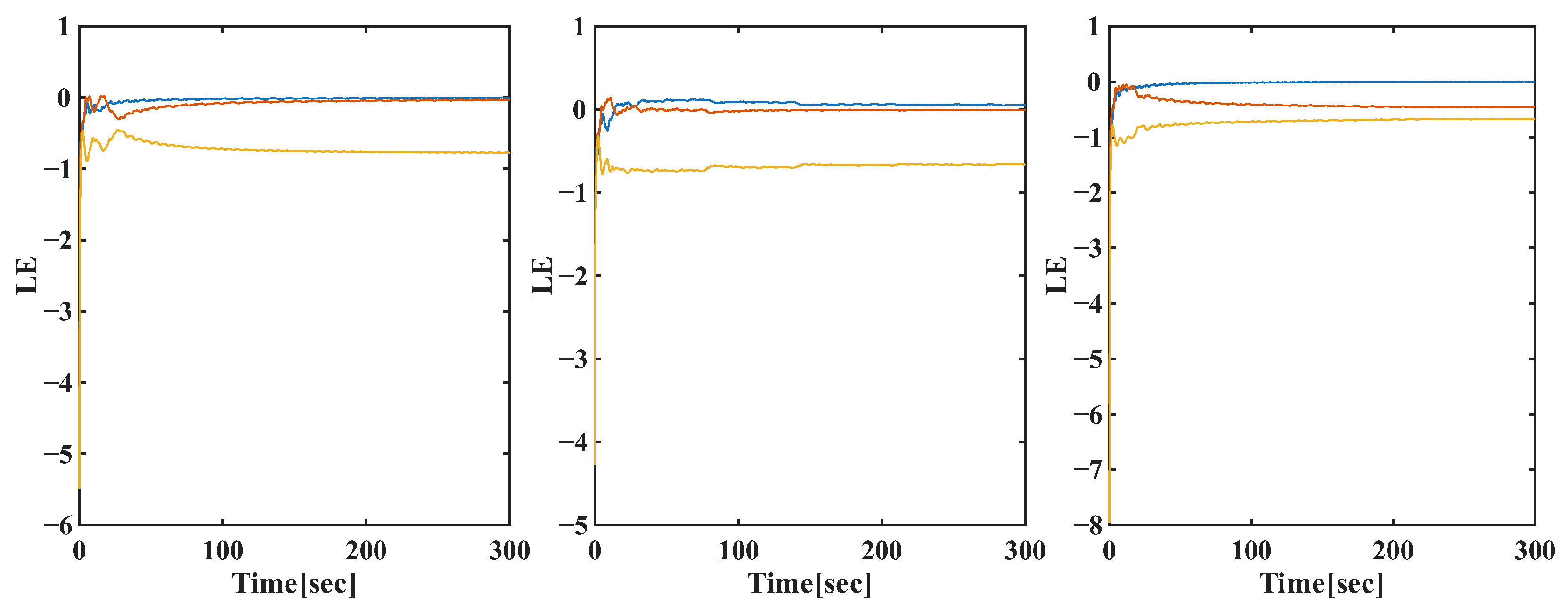

6. Lyapunov Exponent Analysis

7. Bifurcation Analysis

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allogmany, R.; Almuallem, N.A.; Alsemiry, R.D.; Abdoon, M.A. Exploring Chaos in Fractional Order Systems: A Study of Constant and Variable-Order Dynamics. Symmetry 2025, 17, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoon, M.A. Fractional Derivative Approach for Modeling Chaotic Dynamics: Applications in Communication and Engineering Systems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Mathematical Modelling, Applied Analysis and Computation, Beirut, Lebanon, 18–20 April 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 82–95. [Google Scholar]

- Abdoon, M.A.; Alzahrani, A.B. Comparative analysis of influenza modeling using novel fractional operators with real data. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, F.; Abdoon, M.A.; Saadeh, R.; Berir, M.; Qazza, A. A new perspective on the stochastic fractional order materialized by the exact solutions of allen-cahn equation. Int. J. Math. Eng. Manag. Sci. 2023, 8, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Nikan, O.; Avazzadeh, Z. Numerical investigation of generalized tempered-type integrodifferential equations with respect to another function. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2023, 26, 2580–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, A.; Abdurahman, M.; Fouad, H. Existence and stability results for the integrable solution of a singular stochastic fractional-order integral equation with delay. J. Math. Comput. Sci. 2024, 33, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Peng, G. Chaos in Chen’s system with a fractional order. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2004, 22, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petráš, I. The Fractional-Order Lorenz-Type Systems: A Review. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2022, 25, 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petráš, I. Fractional-Order Nonlinear Systems: Modeling, Analysis and Simulation, 1st ed.; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, N.A.; Hameed, T.; Razzaq, O.A.; Ayaz, M. Tracking the chaotic behaviour of fractional-order Chua’s system by Mexican hat wavelet-based artificial neural network. J. Low Freq. Noise Vib. Act. Control 2019, 38, 1279–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniji, A.; Oyeleke, K.; Ojo, K.; Lasisi, A. Modeling and Prediction of Fractional-Order Chaotic Lorenz System Using RNN And LSTM Networks. J. Niger. Assoc. Math. Phys. 2025, 69, 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Chen, G. Chaos in the fractional order Chen system and its control. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2004, 22, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.G. Chaotic dynamics of the fractional-order Lü system and its synchronization. Phys. Lett. A 2006, 354, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbadri, M.; AlMutairi, D.M.; Almutairi, D.K.; Hassan, A.A.; Hdidi, W.; Abdoon, M.A. Efficient Numerical Techniques for Investigating Chaotic Behavior in the Fractional-Order Inverted Rössler System. Symmetry 2025, 17, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chen, G. Chaos and hyperchaos in the fractional-order Rössler equations. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2004, 341, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Wang, M.J. Dynamic analysis of the fractional-order Liu system and its synchronization. Chaos 2007, 17, 033106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almutairi, N.; Saber, S. Application of a time-fractal fractional derivative with a power-law kernel to the Burke-Shaw system based on Newton’s interpolation polynomials. MethodsX 2023, 12, 102510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, M.; Fabrizio, M. On the notion of fractional derivative and applications to the hysteresis phenomena. Meccanica 2017, 52, 3043–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atangana, A.; Araz, S.İ. A novel Covid-19 model with fractional differential operators with singular and non-singular kernels: Analysis and numerical scheme based on Newton polynomial. Alex. Eng. J. 2021, 60, 3781–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbero, G.; Evangelista, L.R.; Zola, R.S.; Lenzi, E.K.; Scarfone, A.M. A Brief Review of Fractional Calculus as a Tool for Applications in Physics: Adsorption Phenomena and Electrical Impedance in Complex Fluids. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Makinde, O.D.; Khan, Z.H.; Ahmad, R.; Khan, W.A. Applications of Fractional Calculus to Thermodynamics Analysis of Hydromagnetic Convection in a Channel. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 149, 107105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padder, A.; Almutairi, L.; Qureshi, S.; Soomro, A.; Afroz, A.; Hincal, E.; Tassaddiq, A. Dynamical analysis of generalized tumor model with Caputo fractional-order derivative. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoon, A.; Elbadri, M.; Alzahrani, A.B.M.; Berir, M.; Ahmed, A. Analyzing the inverted fractional Rössler system through two approaches: Numerical scheme and LHAM. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 115220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allogmany, R.; Sarrah, A.; Abdoon, M.A.; Alanazi, F.J.; Berir, M.; Alharbi, S.A. A Comprehensive Analysis of Complex Dynamics in the Fractional-Order Rössler System. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berir, M.A. A fractional study for solving the smoking model and the chaotic engineering model. In Proceedings of the 2023 2nd International Engineering Conference on Electrical, Energy, and Artificial Intelligence (EICEEAI), Zarqa, Jordan, 27–28 December 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Arneodo, A.; Coullet, P.; Spiegel, E.; Tresser, C. Asymptotic chaos. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 1985, 14, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.G. Chaotic dynamics and synchronization of fractional-order Arneodo’s systems. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2005, 26, 1125–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Fraga, L.G. Multi-Objective Optimization of a Fractional-Order Lorenz System. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zourmba, K.; Effa, J.Y.; Fischer, C.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, J.D.; Moreno-Lopez, M.F.; Tlelo-Cuautle, E.; Nkapkop, J.D.D. Fractional Order 1D Memristive Time-Delay Chaotic System with Application to Image Encryption and FPGA Implementation. Math. Comput. Simul. 2025, 227, 58–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlubny, I. Fractional Differential Equations: An Introduction to Fractional Derivatives, Fractional Differential Equations, to Methods of Their Solution and Some of Their Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998; Volume 198. [Google Scholar]

- Oldham, K.B.; Spanier, J. The Fractional Calculus: Theory and Applications of Differentiation and Integration to Arbitrary Order; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1974; Volume 111. [Google Scholar]

- Podlubny, I. Geometric and Physical Interpretation of Fractional Integration and Fractional Differentiation. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2002, 5, 367–386. [Google Scholar]

- Dorcák, L. Numerical Models for Simulation of the Fractional-Order Control Systems; Technical Report UEF-04-94; The Academy of Sciences, Institute of Experimental Physics: Košice, Slovakia, 1994. [Google Scholar]

| t | u | v | w |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.084866402 | −0.000359913 | −0.352684968 |

| 2 | 0.029306692 | −0.014764026 | 0.154806615 |

| 3 | 0.088279446 | 0.114983775 | 0.098081449 |

| 4 | 0.265233522 | 0.266903696 | 0.258663301 |

| 5 | 0.720892715 | 0.717896785 | 0.684585872 |

| 6 | 1.831494725 | 1.510460716 | 0.557768566 |

| 7 | 2.840953519 | −0.320884293 | −4.456545165 |

| ABM | 2.848573043 | −0.320827460 | −4.456422481 |

| t | u | v | w |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.232508643 | 0.240651821 | 0.251331708 |

| 2 | 0.649028338 | 0.660051456 | 0.641785412 |

| 3 | 1.694547355 | 1.472048881 | 0.740915275 |

| 4 | 2.844600299 | 0.050174902 | −4.218399192 |

| 5 | 1.168512325 | −1.639973110 | 3.096412222 |

| 6 | 1.772563229 | 2.414867495 | 2.506844630 |

| 7 | 3.244323515 | −2.007757272 | −11.172282015 |

| ABM | 3.248662505 | −2.011211727 | −11.128636724 |

| t | u | v | w |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.256492801 | 0.261113269 | 0.272858630 |

| 2 | 0.706399515 | 0.707266309 | 0.669360217 |

| 3 | 1.806973815 | 1.505196683 | 0.596901105 |

| 4 | 2.896784631 | −0.276724010 | −4.710927605 |

| 5 | 0.996149861 | −1.780519168 | 3.702558690 |

| 6 | 1.466933645 | 2.340022923 | 2.410073621 |

| 7 | 3.438597118 | −0.670632299 | −10.351087789 |

| ABM | 3.438284188 | −0.675353571 | −10.310030545 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elbadri, M.; Ashmaig, M.A.M.; Hassan, A.A.; Hdidi, W.; Barakat, H.M.; Al-Mutairi, G.S.; Abdoon, M.A. Exploring Stability and Chaos in the Fractional-Order Arneodo System via Grünwald–Letnikov Scheme. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3925. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243925

Elbadri M, Ashmaig MAM, Hassan AA, Hdidi W, Barakat HM, Al-Mutairi GS, Abdoon MA. Exploring Stability and Chaos in the Fractional-Order Arneodo System via Grünwald–Letnikov Scheme. Mathematics. 2025; 13(24):3925. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243925

Chicago/Turabian StyleElbadri, Mohamed, Manahil A. M. Ashmaig, Abdelgabar Adam Hassan, Walid Hdidi, Hamdy M. Barakat, Ghozail Sh. Al-Mutairi, and Mohamed A. Abdoon. 2025. "Exploring Stability and Chaos in the Fractional-Order Arneodo System via Grünwald–Letnikov Scheme" Mathematics 13, no. 24: 3925. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243925

APA StyleElbadri, M., Ashmaig, M. A. M., Hassan, A. A., Hdidi, W., Barakat, H. M., Al-Mutairi, G. S., & Abdoon, M. A. (2025). Exploring Stability and Chaos in the Fractional-Order Arneodo System via Grünwald–Letnikov Scheme. Mathematics, 13(24), 3925. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243925