Micromechanics-Based Strength Criterion for Root-Reinforced Soil

Abstract

1. Introduction

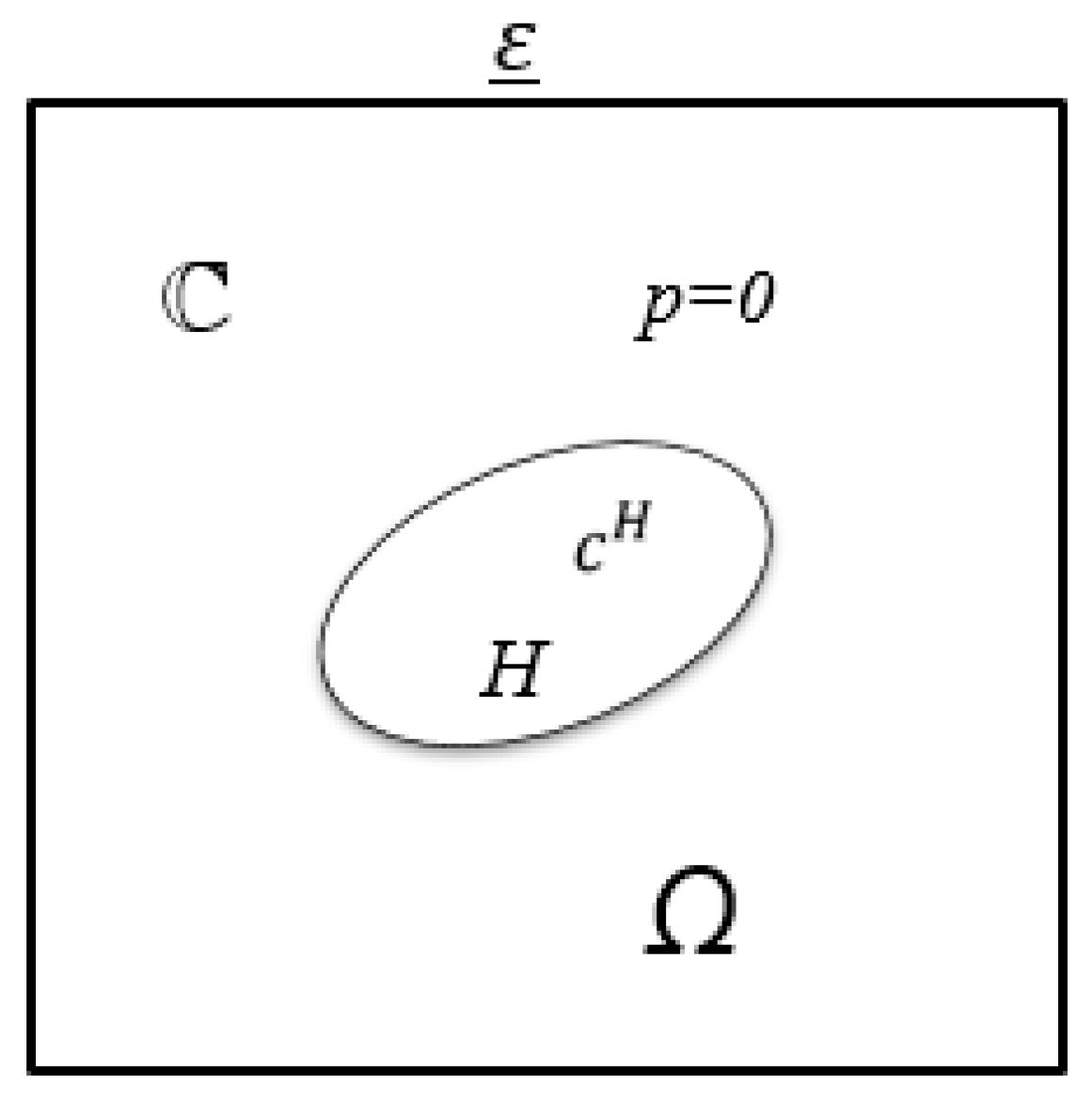

2. Conceptual Framework for Constructing the Strength Criterion

3. Strength Criterion

3.1. Strength Criterion for the Bonded Element (Homogenization I)

3.2. Strength Criterion for the Frictional Element

3.3. Dissipated Energy During the Breakage Process

3.4. Macroscopic Strength Criterion (Homogenization II)

4. Verification of Strength Criterion

4.1. Determination of Strength Parameters

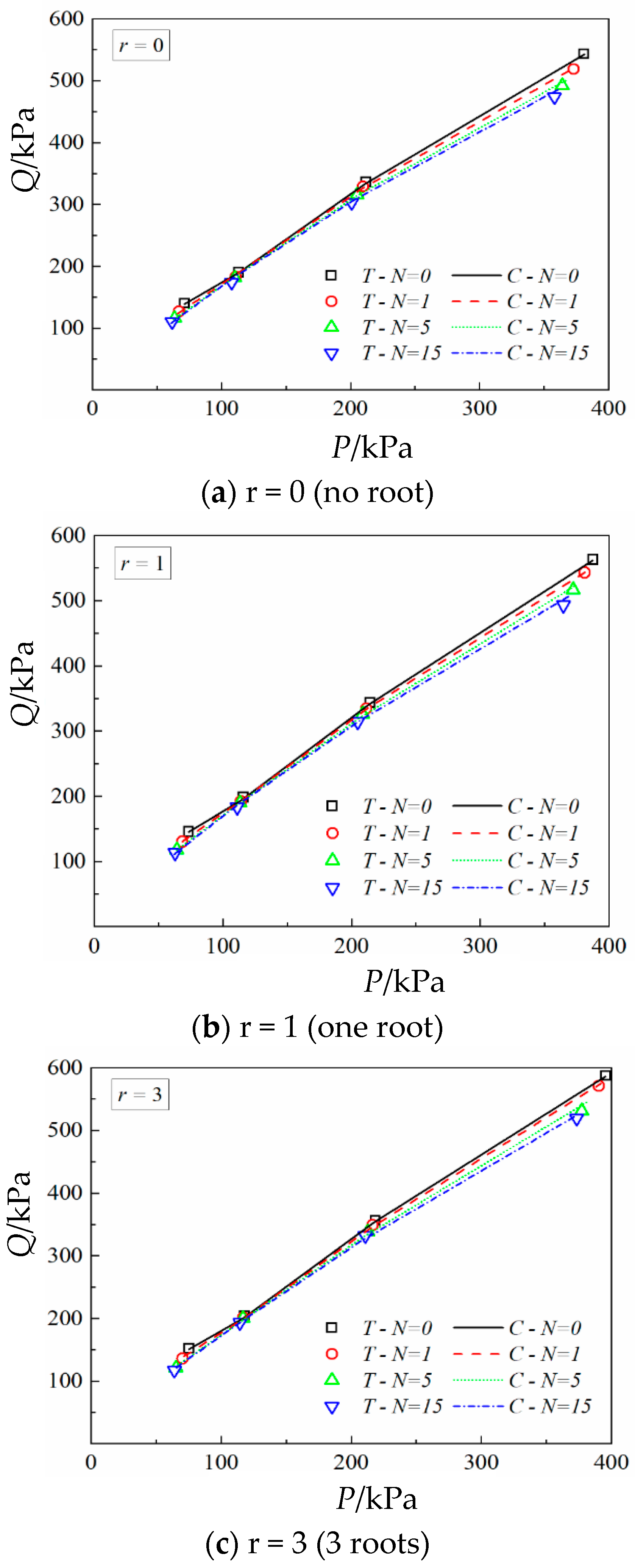

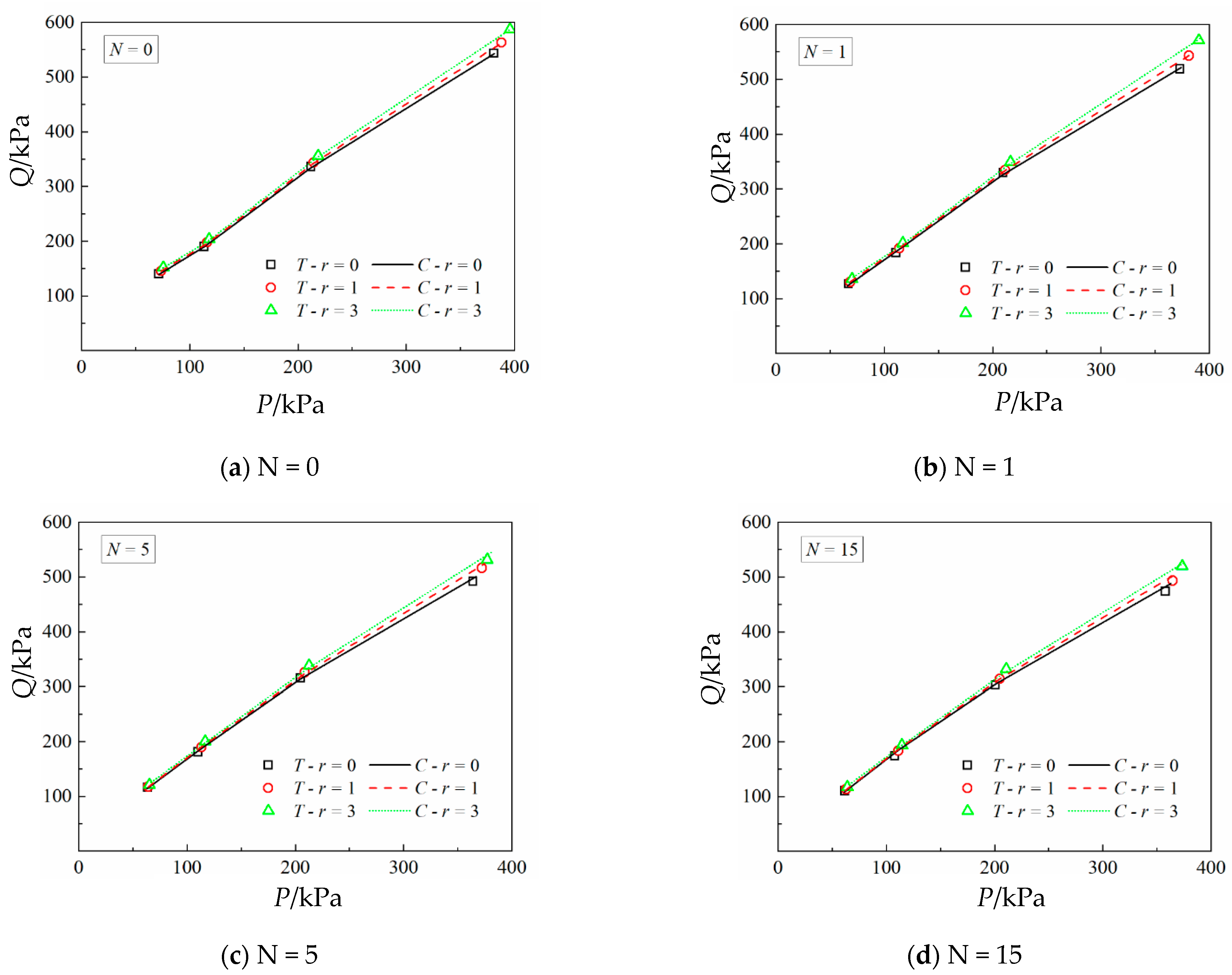

4.2. Experimental Verification

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Deriving the Strain Concentration Tensors of Equation (17)

References

- Wan, Y.; Xue, Q.; Liu, L.; Zhao, L.Y. The role of roots in the stability of landfill clay covers under the effect of dry–wet cycles. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, B.; Peng, J.; Zhan, H.; Wang, X. Mechanical response of root-reinforced loess with various water contents. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 193, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Zong, Q.; Cai, H.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J. Calculation of increased soil shear strength from desert plant roots. Arab. J. Geosci. 2019, 12, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, D.; Cui, Y. Experimental study on the influence of root content on the strength of undisturbed and remolded grass-root-reinforced soils. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2015, 37, 1405–1410. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidifar, H.; Keshavarzi, A.; Truong, P. Enhancement of river bank shear strength parameters using Vetiver grass root system. Arab. J. Geosci. 2018, 11, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffra, C.; Sousa, R.; Sutili, F.; Pinheiro, R. The effect of roots on the shear strength of texturally distinct soils. Floresta Ambiente 2019, 26, e20171018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoza, R.; Oka, L. Measuring the Effect of Grass Roots on Shear Strength Parameters of Sandy Soils. In Geo-Congress 2020; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, J.; Shi, C. Numerical simulation on the influence of plant root morphology on shear strength in the sandy soil, Northwest China. J. Arid Land 2024, 16, 1444–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.C.; Su, C.F. Role of roots in the shear strength of root-reinforced soils with high moisture content. Ecol. Eng. 2008, 33, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, X.; Yu, D.; Zhu, H.; Li, G. Influence of the roots of mixed-planting species on the shear strength of saline loess soil. J. Mt. Sci. 2021, 18, 806–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Ollauri, A.; Mickovski, S.B. Plant-soil reinforcement response under different soil hydrological regimes. Geoderma 2017, 285, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamei, T.; Ahmed, A.; Shibi, T. Effect of freeze–thaw cycles on durability and strength of very soft clay soil stabilised with recycled Bassanite. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2012, 82, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldaood, A.; Bouasker, M.; Al-Mukhtar, M. Impact of freeze–thaw cycles on mechanical behaviour of lime stabilized gypseous soils. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2014, 99, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, N.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, S.; Kong, Y. Effect of freeze-thaw cycles on shear strength of saline soil. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2018, 154, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Ma, D.; Yao, Z. Influence of freeze-thaw cycles on dynamic compressive strength and energy distribution of soft rock specimen. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2018, 153, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Lan, W.; Wang, S. Shear strength and damage mechanism of saline intact loess after freeze-thaw cycling. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2019, 164, 102779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Chen, G.; Niu, F.; Ni, W.; Mu, Y.; Luo, J. Effect of freeze-thaw cycles on uniaxial mechanical properties of cohesive coarse-grained soils. J. Mt. Sci. 2019, 16, 2159–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, A.M. Thermodynamic model of creep at constant stress and constant strain rate. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 1984, 9, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Wang, D.; Ma, W.; Lei, L.; Li, G. A strength criterion for frozen clay considering the influence of stress Lode angle. Can. Geotech. J. 2019, 56, 1557–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Lai, Y.; Wang, C. A strength criterion for frozen sodium sulfate saline soil. Can. Geotech. J. 2016, 53, 1176–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, E. Application of new twin-shear unified strength criterion to frozen soil. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2019, 167, 102857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Liu, E.; Zhu, Z. A strength criterion for frozen moraine soils. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2019, 164, 102786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.M.; Meschke, G. A multiscale homogenization model for strength predictions of fully and partially frozen soils. Acta Geotech. 2018, 13, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, T.; Tanaka, K. Average stress in matrix and average elastic energy of materials with misfitting inclusions. Acta Metall. 1973, 21, 571–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, J.A.; Gathier, B.; Ulm, F.J. Homogenization of cohesive-frictional strength properties of porous composites: Linear comparison composite approach. J. Nanomech. Micromech. 2011, 1, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Xiang, B.; Liu, E.; Zhao, H.; Wu, K.; He, Y. Mechanical properties of rooted soil under freeze–thaw cycles and extended binary medium constitutive model. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshelby, J.D. The Determination of the elastic field of an ellipsoidal inclusion, and related problems. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 1957, 241, 376–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, T.; Cheng, P.C. The Elastic Field Outside an Ellipsoidal Inclusion. J. Appl. Mech. 1959, 252, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, T. Micromechanics of Defects in Solids; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Mesomechanics of Materials; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.Y.; Zhu, Q.Z.; Shao, J.F. A micro-mechanics based plastic damage model for quasi-brittle materials under a large range of compressive stress. Int. J. Plast. 2018, 100, 156–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaneda, P.P. Second-order homogenization estimates for nonlinear composites incorporating field fluctuations: I—Theory. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2002, 50, 737–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Pamies, O.; Ponte Castaneda, P. Second-order homogenization estimates incorporating field fluctuations in finite elasticity. Math. Mech. Solids 2004, 9, 243–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liu, E.; Zhi, B. An elastic-plastic model for frozen soil from micro to macro scale. Appl. Math. Model. 2021, 91, 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormieux, L.; Molinari, A.; Kondo, D. Micromechanical approach to the behavior of poroelastic materials. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2002, 50, 2203–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormieux, L.; Lemarchand, E.; Kondo, D.; Brach, S. Strength criterion of porous media: Application of homogenization techniques. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2017, 9, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormieux, L.; Kondo, D.; Ulm, F.-J. Microporomechanics; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Maghous, S.; Dormieux, L.; Barthelemy, J.F. Micromechanical approach to the strength properties of frictional geomaterials. Eur. J. Mech.-A/Solids 2009, 28, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; Yu, H.-S.; Zhou, C.; Nie, Q.; Luo, K. A binary-medium constitutive model for artificially structured soils based on the disturbed state concept (DSC) and homogenization theory. Int. J. Geomech. 2017, 17, 04016154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Symbol | Value | Determining Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bonded element | /kPa | Triaxial tests of the samples without roots and without freeze–thaw cycling at 0.2% axial strain | |

| /kPa | |||

| /kPa | 135,000 | Directly through laboratory compression tests | |

| /kPa | 20,250 | ||

| Frictional elements | /kPa | Triaxial tests of the remolded samples | |

| /kPa | |||

| 0.01 | By comparing the tested and computed results, fitting of the strengths measured on the remolded specimens is achieved by trial and error or optimization methods By trial and error | ||

| 1.185 | |||

| /kPa | |||

| Breakage ratio | |||

| 0.155 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luo, W.; Cao, F.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, G.; Liu, E. Micromechanics-Based Strength Criterion for Root-Reinforced Soil. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3890. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233890

Luo W, Cao F, Wang Y, Xiao G, Liu E. Micromechanics-Based Strength Criterion for Root-Reinforced Soil. Mathematics. 2025; 13(23):3890. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233890

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuo, Wei, Fu Cao, Yang Wang, Guiyou Xiao, and Enlong Liu. 2025. "Micromechanics-Based Strength Criterion for Root-Reinforced Soil" Mathematics 13, no. 23: 3890. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233890

APA StyleLuo, W., Cao, F., Wang, Y., Xiao, G., & Liu, E. (2025). Micromechanics-Based Strength Criterion for Root-Reinforced Soil. Mathematics, 13(23), 3890. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233890