Efficient and Interpretable ECG Abnormality Detection via a Lightweight DSCR-BiGRU-Attention Network with Demographic Fusion

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We designed a lightweight network architecture that combines DSCR, BiGRU, and attention modules, significantly reducing parameter count and computational cost while maintaining high classification accuracy.

- We introduced the ASF module, which integrates age and sex information to enhance the recognition of ECG abnormalities and improve personalized diagnostic performance.

- We validated DBA-ASFNet on the PTB-XL and CPSC2018 datasets, achieving competitive multi-label classification performance. Its real-time inference capability was further confirmed on a Raspberry Pi 5.

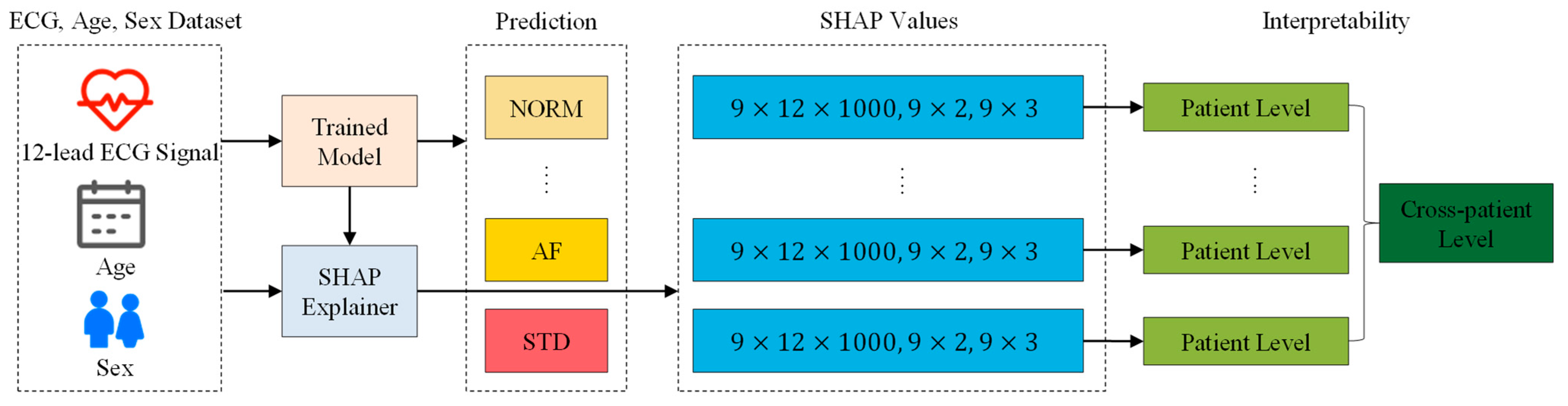

- We used the SHAP framework to interpret model predictions at both the patient and cross-patient levels, revealing the impact of demographic features and further enhancing model transparency and clinical applicability.

2. Related Works

2.1. Lightweighting

2.2. Demographic Fusion

2.3. Interpretability

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Datasets

3.1.1. PTB-XL Dataset

3.1.2. CPSC2018 Dataset

3.2. Data Preprocessing

3.3. DBA-ASFNet

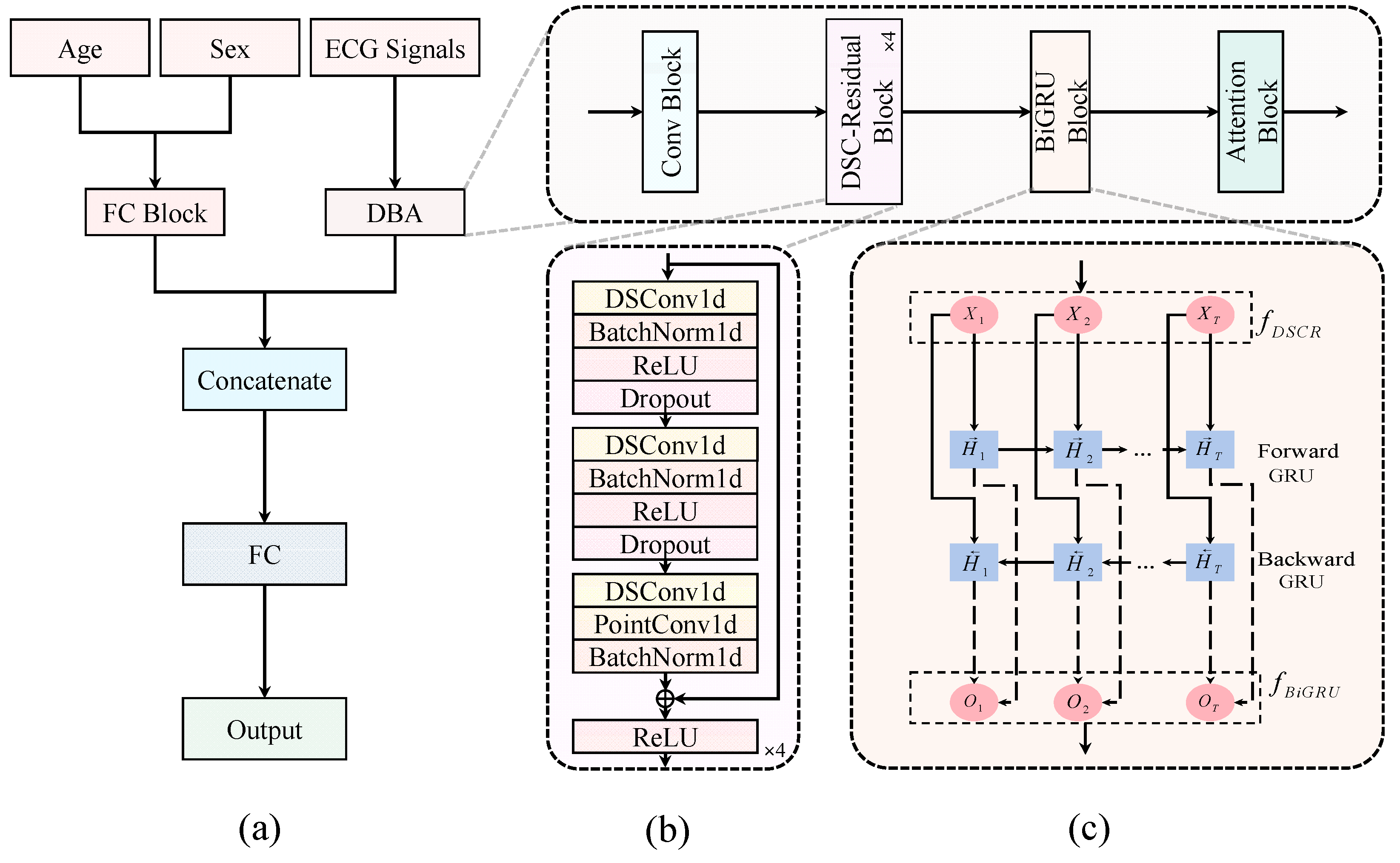

- (1)

- DBA branch: 10-s, 12-lead ECGs pass through an initial convolutional block. Then, four stacked DSCR blocks produce a compact temporal feature map X. A BiGRU with 32 hidden units per direction processes sequence X to obtain H. Finally, H is attention-pooled into a sixty-four-dimensional vector

- (2)

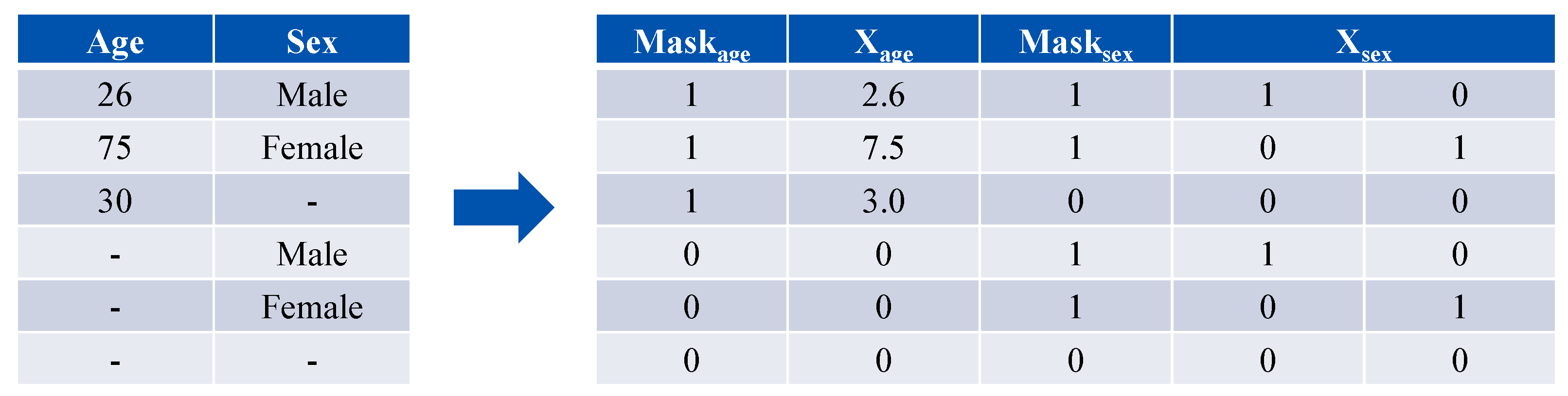

- Demographic branch: Age is normalized (age/10) and sex is one-hot encoded into a two-dimensional vector. Each is paired with a presence mask, resulting in a combined five-dimensional input vector. A fully connected block maps this vector to an embedding vector .

- (3)

- Fusion and classification: The vectors z and g are concatenated [z; g] and fed into a final FC layer with a sigmoid activation function to generate the C multi-label predictions.

3.4. SHAP Interpretability Analysis

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Evaluation Metrics and Settings

4.2. Comparative Experiments

4.3. Ablation Experiments

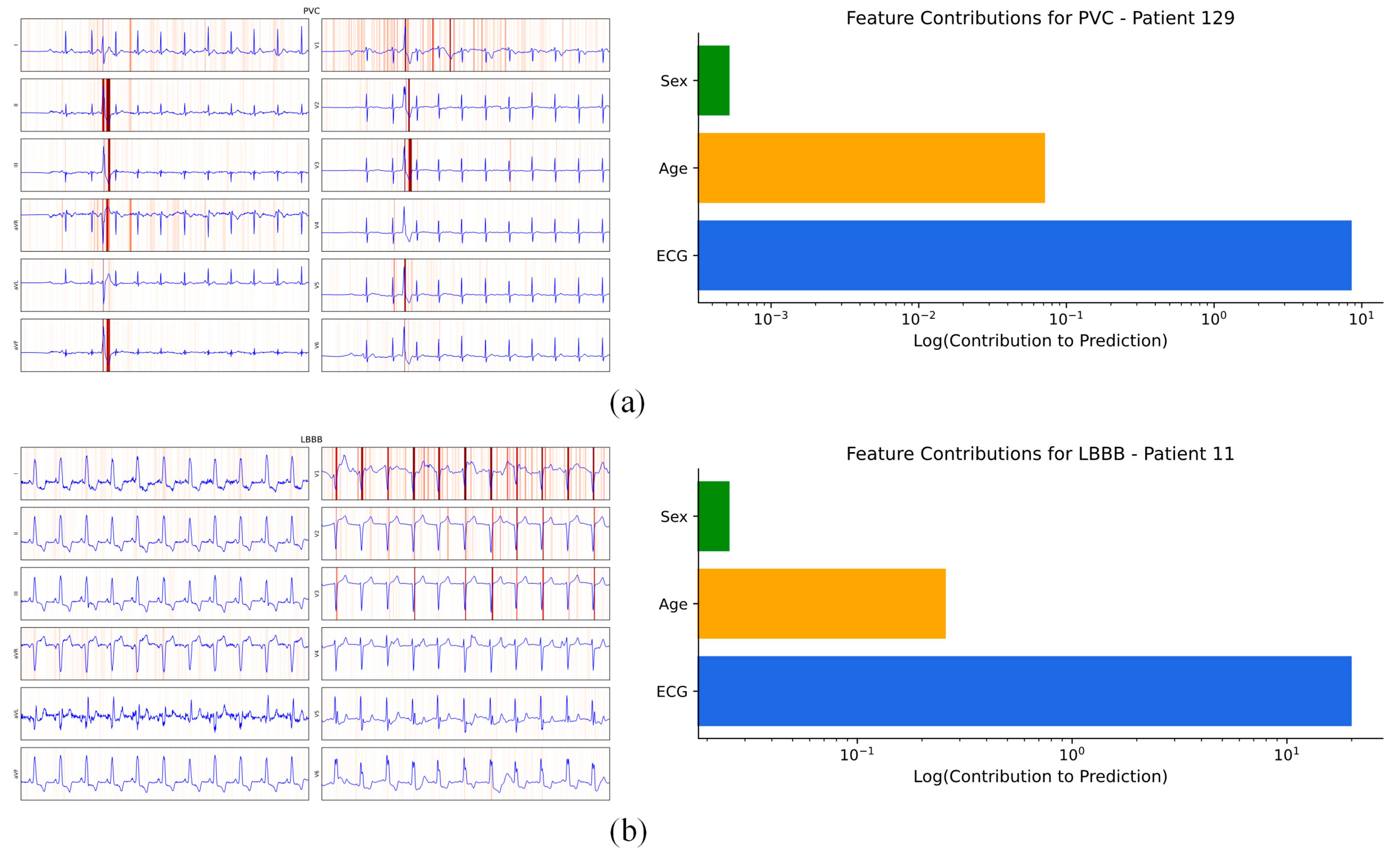

4.4. Interpretability of Model Output

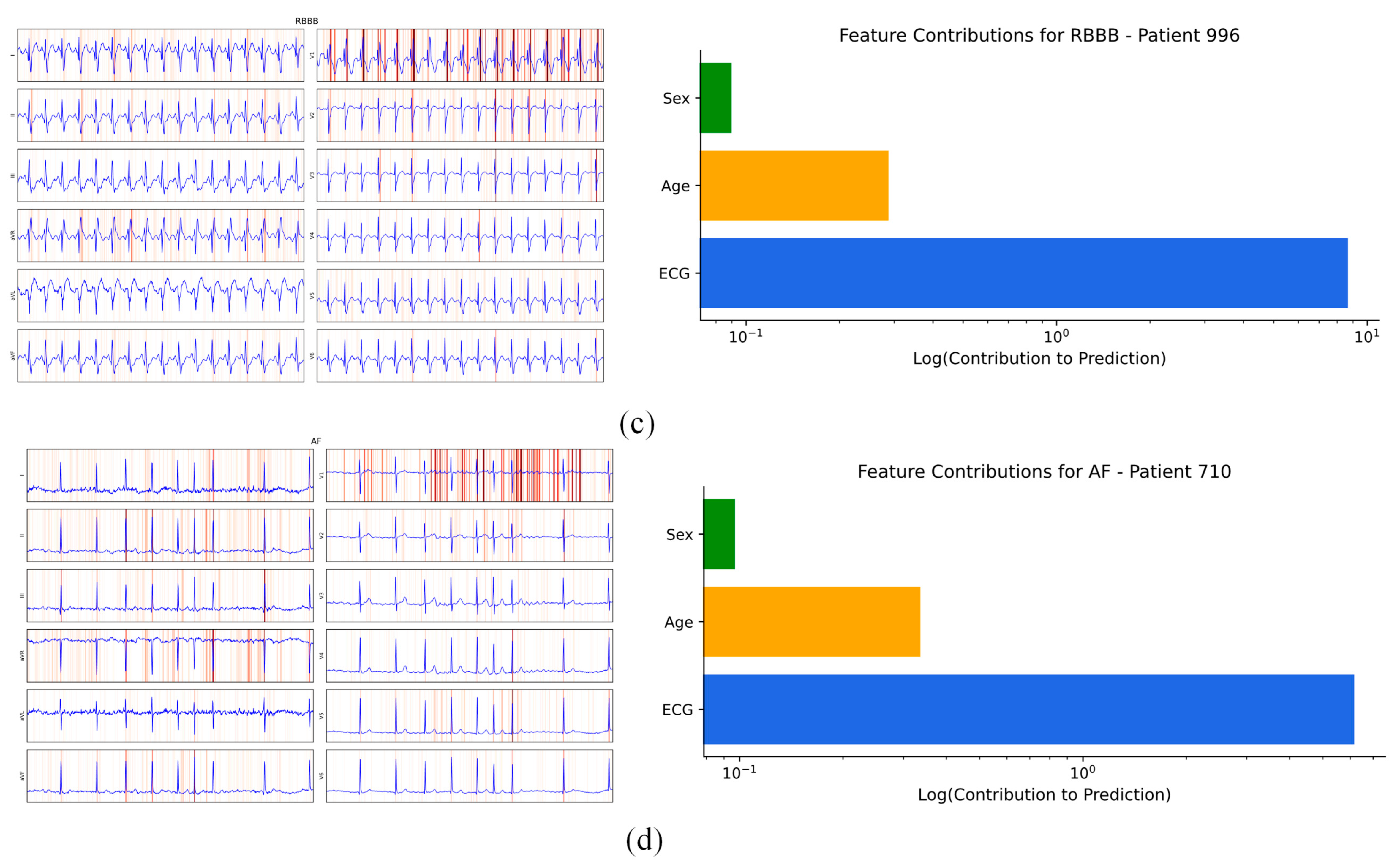

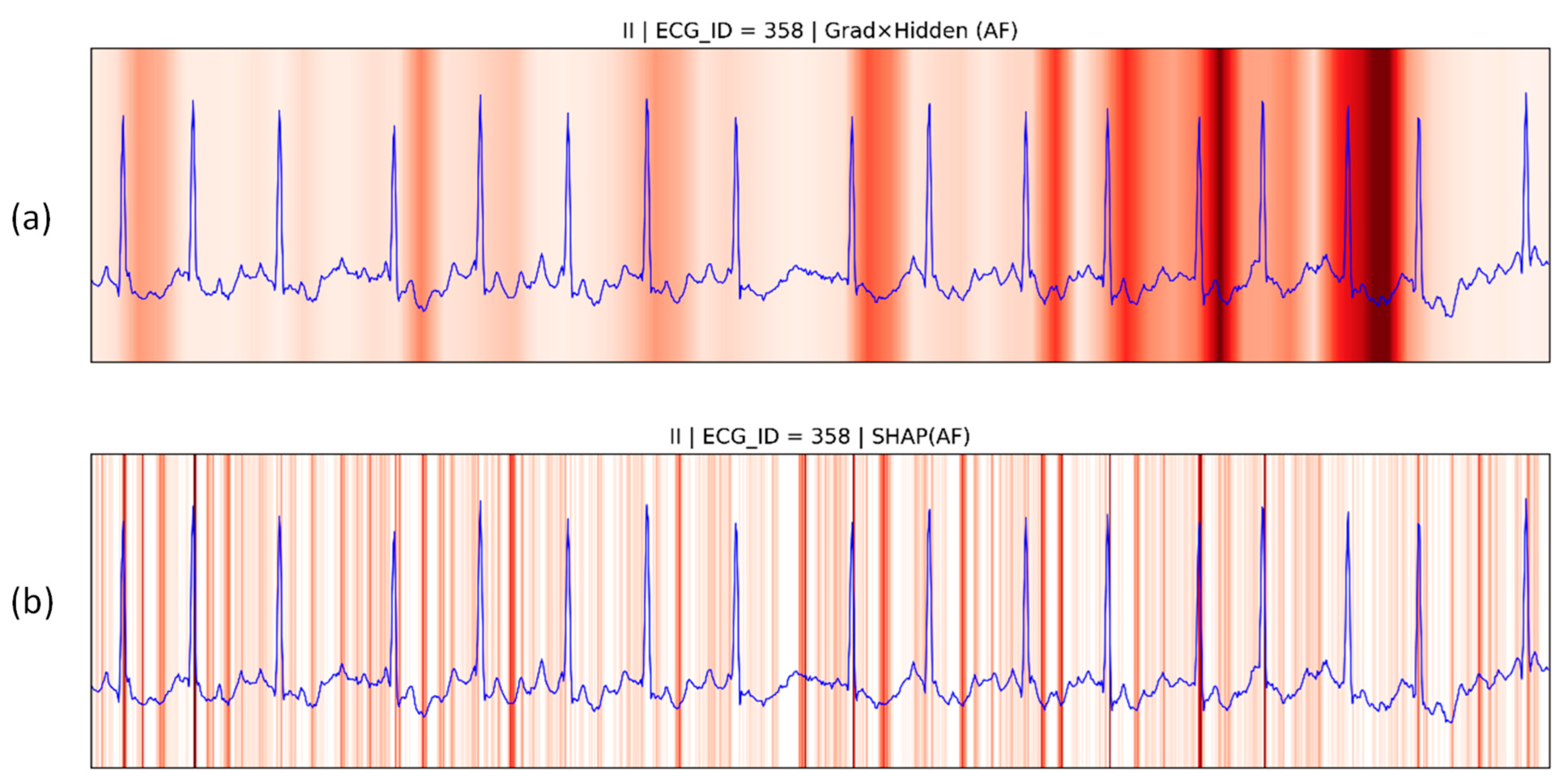

4.4.1. Patient Individual Level

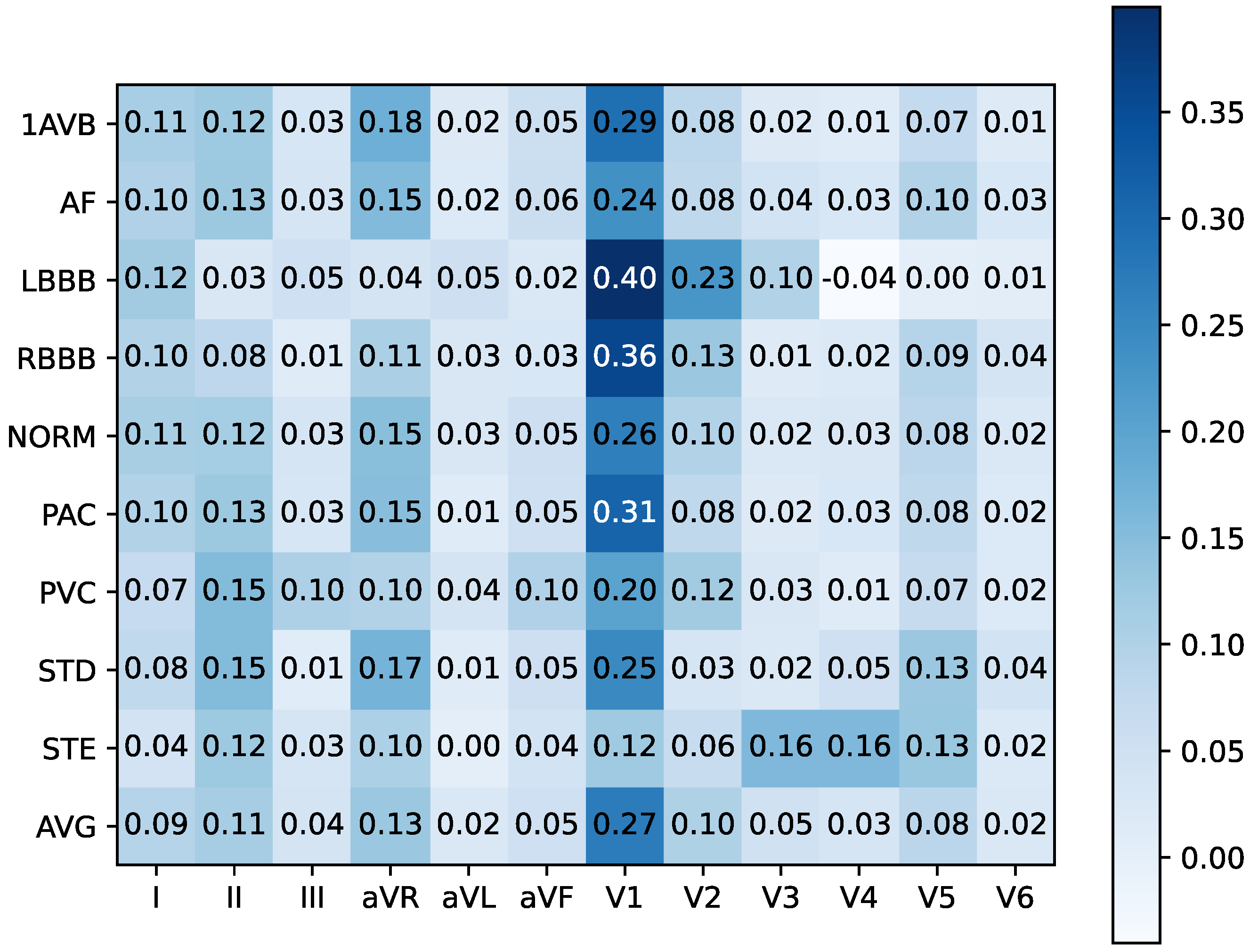

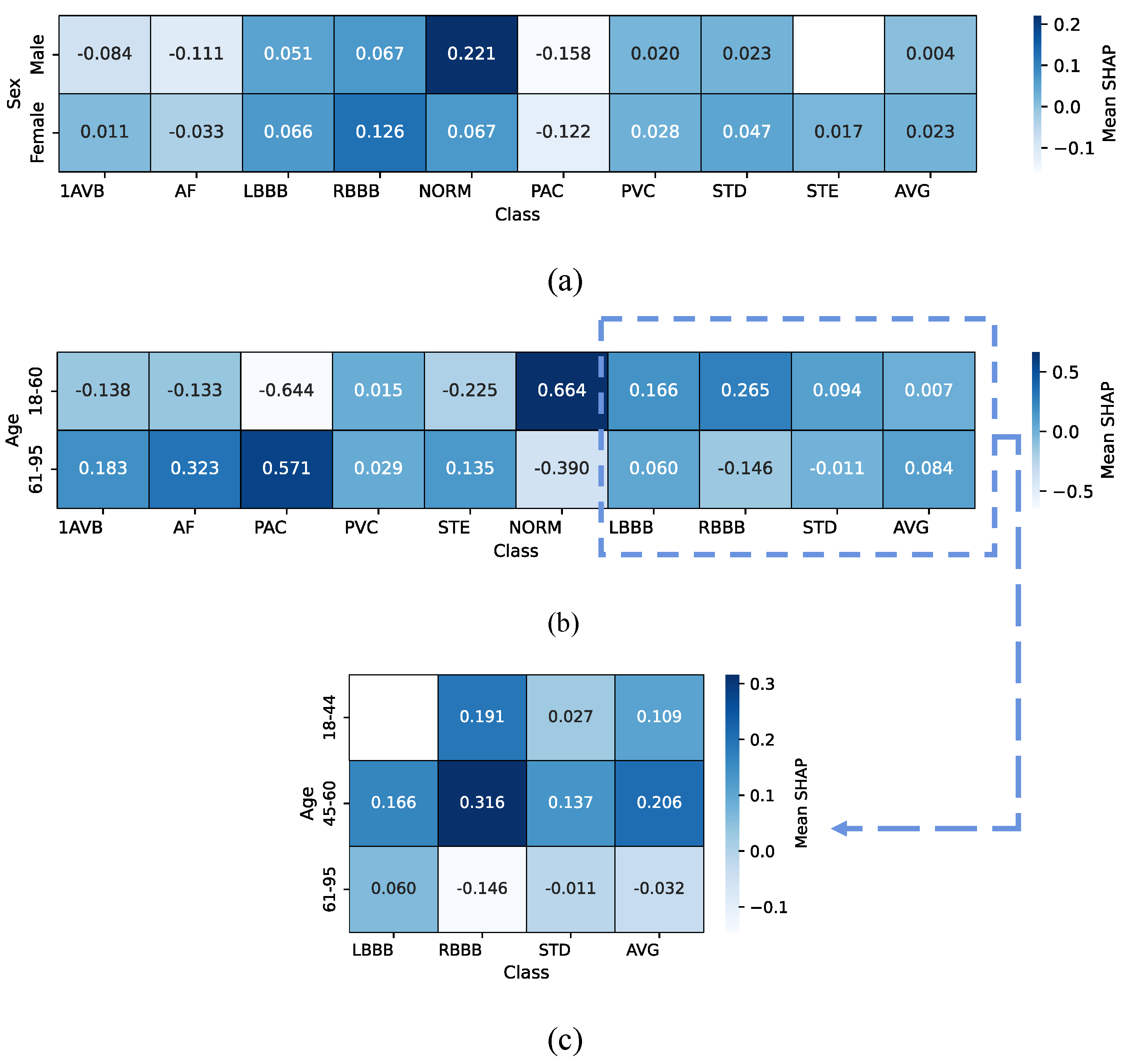

4.4.2. Cross-Patient Global Level

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mensah, G.A.; Fuster, V.; Murray, C.J.L.; Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Abate, Y.H.; Abbasian, M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdollahi, A.; Abdollahi, M.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risks, 1990–2022. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 82, 2350–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, G.A.; Fuster, V.; Roth, G.A. A Heart-Healthy and Stroke-Free World. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 82, 2343–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denysyuk, H.V.; Pinto, R.J.; Silva, P.M.; Duarte, R.P.; Marinho, F.A.; Pimenta, L.; Gouveia, A.J.; Gonçalves, N.J.; Coelho, P.J.; Zdravevski, E.; et al. Algorithms for Automated Diagnosis of Cardiovascular Diseases Based on ECG Data: A Comprehensive Systematic Review. Heliyon 2023, 9, 13601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Cheng, C.; Yin, H.; Li, X.; Zuo, P.; Ding, J.; Lin, F.; Wang, J.; Zhou, B.; Li, Y.; et al. Automatic Multilabel Electrocardiogram Diagnosis of Heart Rhythm or Conduction Abnormalities with Deep Learning: A Cohort Study. Lancet Digit. Health 2020, 2, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Guo, C. Deep Learning and Electrocardiography: Systematic Review of Current Techniques in Cardiovascular Disease Diagnosis and Management. Biomed. Eng. OnLine 2025, 24, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Qin, L. Deep Learning in ECG Diagnosis: A Review. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 227, 107187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Herbozo Contreras, L.F.; Leung, W.H.; Yu, L.; Truong, N.D.; Nikpour, A.; Kavehei, O. Efficient Edge-AI Models for Robust ECG Abnormality Detection on Resource-Constrained Hardware. J Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2024, 17, 879–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Shuttleworth, K.M.J. Medical Artificial Intelligence and the Black Box Problem: A View Based on the Ethical Principle of “Do No Harm”. Intell. Med. 2024, 4, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, D.; Hughes, J.W.; Rogers, A.J.; Kang, G.; Narayan, S.M.; Ashley, E.A.; Perez, M.V. Race, Sex, and Age Disparities in the Performance of ECG Deep Learning Models Predicting Heart Failure. Circ. Heart Fail. 2024, 17, 010879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, K.H.; Pham, H.H.; Nguyen, T.B.T.; Nguyen, T.A.; Thanh, T.N.; Do, C.D. LightX3ECG: A Lightweight and eXplainable Deep Learning System for 3-Lead Electrocardiogram Classification. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2023, 85, 104963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamatsaz, N.; Tabatabaei, L.; Yazdchi, M.; Payan, H.; Alamatsaz, N.; Nasimi, F. A Lightweight Hybrid CNN-LSTM Explainable Model for ECG-Based Arrhythmia Detection. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 90, 105884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Shi, S.; Wang, Q.; Yu, Y.; Liu, Q. Research on a Lightweight Arrhythmia Classification Model Based on Knowledge Distillation for Wearable Single-Lead ECG Monitoring Systems. Sensors 2024, 24, 7896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Diao, X.; Huo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Fan, X.; Zhao, W. Masked Transformer for Electrocardiogram Classification. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2309.07136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Khatibi, E.; Kazemi, K.; Azimi, I.; Mousavi, S.; Malik, S.; Rahmani, A.M. TransECG: Leveraging Transformers for Explainable ECG Re-Identification Risk Analysis. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.13495. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.-H.; Lin, C.-S.; Luo, Y.-S.; Lee, Y.-T.; Lin, C. Electrocardiogram-Based Heart Age Estimation by a Deep Learning Model Provides More Information on the Incidence of Cardiovascular Disorders. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 754909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawshani, A.; Rawshani, A.; Smith, G.; Boren, J.; Bhatt, D.L.; Börjesson, M.; Engdahl, J.; Kelly, P.; Louca, A.; Ramunddal, T.; et al. Integrating Deep Learning with ECG, Heart Rate Variability and Demographic Data for Improved Detection of Atrial Fibrillation. Open Heart 2025, 12, 003185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, T.A.A.; Zahid, M.S.M.; Ali, W.; Hassan, S.U. B-LIME: An Improvement of LIME for Interpretable Deep Learning Classification of Cardiac Arrhythmia from ECG Signals. Processes 2023, 11, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.; Afghah, F.; Acharya, U.R. HAN-ECG: An Interpretable Atrial Fibrillation Detection Model Using Hierarchical Attention Networks. Comput. Biol. Med. 2020, 127, 104057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goettling, M.; Hammer, A.; Malberg, H.; Schmidt, M. xECGArch: A Trustworthy Deep Learning Architecture for Interpretable ECG Analysis Considering Short-Term and Long-Term Features. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abgrall, G.; Holder, A.L.; Chelly Dagdia, Z.; Zeitouni, K.; Monnet, X. Should AI Models Be Explainable to Clinicians? Crit. Care 2024, 28, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michiels, J.; Suykens, J.; De Vos, M. Explaining the Model and Feature Dependencies by Decomposition of the Shapley Value. Decis. Support Syst. 2024, 182, 114234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, P.; Strodthoff, N.; Bousseljot, R.-D.; Kreiseler, D.; Lunze, F.I.; Samek, W.; Schaeffter, T. PTB-XL, a Large Publicly Available Electrocardiography Dataset. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, J.L.; Zywietz, C.; Rubel, P.; Degani, R.; Macfarlane, P.W.; Van Bemmel, J.H. A Standard Communications Protocol for Computerized Electrocardiography. J. Electrocardiol. 1991, 24, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Liu, C.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, X.; Wu, X.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y.; Ma, C.; Wei, S.; He, Z.; et al. An Open Access Database for Evaluating the Algorithms of Electrocardiogram Rhythm and Morphology Abnormality Detection. J. Med. Imaging Health Inform. 2018, 8, 1368–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Wang, N.; Feng, P.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, B. A Multi-Resolution Mutual Learning Network for Multi-Label ECG Classification. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), Lisbon, Portugal, 3 December 2024; pp. 3303–3306. [Google Scholar]

- Van Alsté, J.A.; Van Eck, W.; Herrmann, O.E. ECG Baseline Wander Reduction Using Linear Phase Filters. Comput. Biomed. Res. 1986, 19, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V. A Study on Data Scaling Methods for Machine Learning. Int. J. Glob. Acad. Sci. Res. 2022, 1, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Chen, L. Leadwise Clustering Multi-Branch Network for Multi-Label ECG Classification. Med. Eng. Phys. 2024, 130, 104196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, G.; Tjortjis, C. Adaptive Sliding Window Normalization. Inf. Syst. 2025, 129, 102515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Van Merrienboer, B.; Gulcehre, C.; Bahdanau, D.; Bougares, F.; Schwenk, H.; Bengio, Y. Learning Phrase Representations Using RNN Encoder–Decoder for Statistical Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Doha, Qatar, 3 June 2014; pp. 1724–1734. [Google Scholar]

- Strodthoff, N.; Wagner, P.; Schaeffter, T.; Samek, W. Deep Learning for ECG Analysis: Benchmarks and Insights from PTB-XL. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2021, 25, 1519–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyotishi, D.; Dandapat, S. An Attentive Spatio-Temporal Learning-Based Network for Cardiovascular Disease Diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2023, 53, 4661–4671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, H. Fusing Deep Metric Learning with KNN for 12-Lead Multi-Labelled ECG Classification. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2023, 85, 104849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elharrouss, O.; Mahmood, Y.; Bechqito, Y.; Serhani, M.A.; Badidi, E.; Riffi, J.; Tairi, H. Loss Functions in Deep Learning: A Comprehensive Review. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.04242. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Yan, W.; Oates, T. Time Series Classification from Scratch with Deep Neural Networks: A Strong Baseline. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Anchorage, AK, USA, 14–17 May 2017; pp. 1578–1585. [Google Scholar]

- Fawaz, H.I.; Lucas, B.; Forestier, G.; Pelletier, C.; Schmidt, D.F.; Weber, J.; Webb, G.I.; Idoumghar, L.; Muller, P.-A.; Petitjean, F. InceptionTime: Finding AlexNet for Time Series Classification. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2020, 34, 1936–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, J.; Li, M. Bag of Tricks for Image Classification with Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 558–567. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chen, B.; Wang, W.; Chen, L.-C.; Tan, M.; Chu, G.; Vasudevan, V.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, R.; et al. Searching for MobileNetV3. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 1314–1324. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Q.; Wang, R.; Fan, X.; Liu, J.; Li, Y. Multi-Class Arrhythmia Detection from 12-Lead Varied-Length ECG Using Attention-Based Time-Incremental Convolutional Neural Network. Inf. Fusion 2020, 53, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Lian, C.; Xu, B.; Zhou, Q.; Su, Y.; Zeng, Z. Large Language Model-Assisted Multi-Scale Hierarchical Classification of ECG Signals. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 324, 113807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Fu, B.; Li, R.; Li, R.; Chen, D.Z.; Liu, Y.; Xie, G.; Li, K. A Dual-Branch Convolutional Neural Network with Domain-Informed Attention for Arrhythmia Classification of 12-Lead Electrocardiograms. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 139, 109480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, M.-S. Current Concepts of Premature Ventricular Contractions. J. Lifestyle Med. 2013, 3, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, N.Y.; Witt, C.M.; Oh, J.K.; Cha, Y.-M. Left Bundle Branch Block: Current and Future Perspectives. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2020, 13, 008239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alventosa-Zaidin, M.; Guix Font, L.; Benitez Camps, M.; Roca Saumell, C.; Pera, G.; Alzamora Sas, M.T.; Forés Raurell, R.; Rebagliato Nadal, O.; Dalfó-Baqué, A.; Brugada Terradellas, J. Right Bundle Branch Block: Prevalence, Incidence, and Cardiovascular Morbidity and Mortality in the General Population. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2019, 25, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayano, Y.M.; Schwenker, F.; Dufera, B.D.; Debelee, T.G.; Ejegu, Y.G. Interpretable Hybrid Multichannel Deep Learning Model for Heart Disease Classification Using 12-Lead ECG Signal. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 94055–94080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, E.; Ruiperez-Campillo, S.; Casado-Arroyo, R.; Merino, J.L.; Vogt, J.E.; Castells, F.; Millet, J. The Art of Selecting the ECG Input in Neural Networks to Classify Heart Diseases: A Dual Focus on Maximizing Information and Reducing Redundancy. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1452829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Maria, B.; Parati, M.; Dalla Vecchia, L.A.; La Rovere, M.T. Day and Night Heart Rate Variability Using 24-h ECG Recordings: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis Using a Gender Lens. Clin. Auton. Res. 2023, 33, 821–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, C.; Koivumäki, J.; Pekkanen-Mattila, M.; Aalto-Setälä, K. Sex Differences in Heart: From Basics to Clinics. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2022, 27, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.-M.; Huang, C.-H.; Shih, E.S.C.; Hu, Y.-F.; Hwang, M.-J. Detection and Classification of Cardiac Arrhythmias by a Challenge-Best Deep Learning Neural Network Model. iScience 2020, 23, 100886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Isla, G.; Mainardi, L.; Corino, V.D.A. A Detector for Premature Atrial and Ventricular Complexes. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 678558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Ye, M.; Zhang, M.; Yao, F.; Cheng, Y. Incidence and Risk Factors Associated with Atrioventricular Block in the General Population: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study and Cardiovascular Health Study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2024, 24, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, A.D.; Middeldorp, M.E.; Van Gelder, I.C.; Albert, C.M.; Sanders, P. Epidemiology and Modifiable Risk Factors for Atrial Fibrillation. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verardi, R.; Iannopollo, G.; Casolari, G.; Nobile, G.; Capecchi, A.; Bruno, M.; Lanzilotti, V.; Casella, G. Management of Acute Coronary Syndrome in Elderly Patients: A Narrative Review through Decisional Crossroads. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hotspots | Model | Data Set | Method | Metrics & Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lightweighting | Lightx3ECG [10] | CPSC2018 Chapman | 3-branch 1D-CNN attention fusion pruning | 9 classes: Pre 82.09, Rec 78.62, F1 80.04, Acc 96.28 4 classes: Pre 97.36, Rec 97.03, F1 97.18, Acc 98.73 |

| CNN-LSTM [11] | MIT-BIH & LTAF | Parallel shallow 1D-CNN 1-layer LSTM | 9 classes: Acc 98.24, Sen 86.1, Spe 97.5 | |

| CNN-SE-LSTM [12] | Chapman | Knowledge distillation | 4 classes: Pre 82.09, Rec 78.62, F1 80.04, Acc: 96.28 | |

| MTECG [13] | Private dataset | MAE-style pretraining | 28 classes: F1 76.5 | |

| Demographic fusion | TransECG [14] | MIT-BIH | age, sex | 2 classes: Acc 89.9, Pre 90.0, F1 89.9 5 classes: Acc 89.9, Pre 90.1, F1 89.9 |

| CNN [15] | Private dataset | age, sex | - | |

| AlexNet [16] | PTB-XL | HRV, age, sex | 2 classes: Sen 92.25, Auc 96.29, Spe 92.03 | |

| Interpretability | CNN-GRU [17] | MIT-BIH | B-LIME | - |

| HAN-ECG [18] | MIT-BIH AFIB | Attention mechanism | - | |

| xECGArch [19] | PTB-XL CPSC 2018 Chapman | SHAP | - |

| Stage | DBA Backbone | Output | ASF | Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input | 12-lead ECG | 12 × 1000 | Masked [Age, Sex] | 5 × 1 |

| Conv | Conv (7, 32), stride 2 | 32 × 500 | FC (5 → 4) | g: 4 × 1 |

| DSCR 1 | DSConv (7/5/3, 32), stride 1/1/1 | 32 × 500 | ||

| DSCR 2 | 3 × {DSConv (7/5/3, 32), stride 1/1/2} | X:32 × 63 | ||

| BiGRU | BiGRU (hidden = 32) | H:63 × 64 | ||

| Attention | Equation (5) | z:64 × 1 | ||

| Concatenate | [z; g] | 68 × 1 | — | — |

| Classifier | FC (68 → C), Sigmoid | C × 1 | — | — |

| Method | PTB-XL | CPSC2018 | Param (M) | Flops (M) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Diag. | Sub-Diag. | Super-Diag. | Form | Rhythm | ||||

| Fcn_wang [35] * | 89.06 | 91.72 | 90.95 | 91.26 | 79.89 | 87.46 | 89.97 | 0.28 | 276.33 |

| Resnet1d_wang [35] * | 91.15 | 92.98 | 92.74 | 91.67 | 83.33 | 88.41 | 93.28 | 0.29 | 33.40 |

| InceptionTime [36] * | 90.78 | 91.96 | 92.78 | 91.88 | 85.47 | 92.15 | 93.22 | 0.47 | 475.52 |

| Xresnet1d101 [37] * | 90.83 | 90.53 | 91.27 | 89.76 | 79.72 | 92.96 | 92.36 | 1.53 | 140.64 |

| MobileNetV3 [38] * | 89.96 | 87.58 | 88.28 | 90.52 | 76.63 | 94.27 | 93.04 | 1.48 | 20.67 |

| ATI-CNN [39] | 89.29 | 91.11 | 89.89 | 92.11 | 82.71 | 96.84 | 94.65 | 5.00 | 287.34 |

| Chen et al. [40] | - | 85.05 | 88.02 | 91.30 | - | - | - | 3.75 | - |

| DCRR-Net [41] | - | - | - | - | - | 93.60 | - | 0.17 | - |

| Proposed (100 Hz) | 92.48 | 92.13 | 90.32 | 91.66 | 83.91 | 95.88 | 94.92 | 0.03 | 6.43 |

| Proposed (250 Hz) Proposed (500 Hz) | - - | - - | - - | - - | - - | - - | 95.03 94.18 | 0.03 0.03 | 16.07 32.12 |

| Model | PTB-XL | CPSC2018 | Param (M) | Flops (M) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Diag. | Sub-Diag. | Super-Diag. | Form | Rhythm | ||||

| DSCR Block ×1 + BiGRU | 91.70 | 91.30 | 90.99 | 91.56 | 84.89 | 93.31 | 94.38 | 0.02 | 9.94 |

| DSCR Block ×2 + BiGRU | 91.83 | 91.46 | 92.23 | 91.16 | 80.36 | 94.78 | 94.35 | 0.02 | 7.93 |

| DSCR Block ×3 + BiGRU | 91.54 | 91.16 | 92.08 | 91.70 | 83.35 | 95.23 | 94.63 | 0.03 | 6.92 |

| DSCR Block ×5 + BiGRU | 90.89 | 91.65 | 90.89 | 91.18 | 83.68 | 96.05 | 94.33 | 0.04 | 6.68 |

| DSCR Block ×6 + BiGRU | 91.42 | 91.92 | 90.92 | 91.72 | 84.10 | 95.66 | 94.82 | 0.04 | 6.93 |

| DSCR Block ×4 + GRU | 91.12 | 90.90 | 90.76 | 91.73 | 80.29 | 96.00 | 93.66 | 0.03 | 6.02 |

| DSCR Block ×4 + BiGRU | 92.48 | 92.13 | 90.32 | 91.66 | 83.91 | 95.88 | 94.92 | 0.03 | 6.43 |

| Model | PTB-XL | CPSC2018 | Param (M) | Flops (M) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Diag. | Sub-Diag. | Super-Diag. | Form | Rhythm | ||||

| DBA | 91.54 | 91.42 | 90.72 | 91.32 | 83.80 | 95.81 | 94.56 | 0.03 | 6.43 |

| 95%CI | 90.45–92.58 | 90.12–92.57 | 89.18–92.08 | 90.54–92.12 | 80.99–86.04 | 93.63–97.22 | 92.95–95.74 | ||

| DBA + ASF | 92.48 | 92.13 | 90.32 | 91.66 | 83.91 | 95.88 | 94.92 | 0.03 | 6.43 |

| 95%CI | 91.51–93.30 | 91.15–93.09 | 88.22–92.26 | 90.82–92.44 | 81.71–86.42 | 93.21–97.47 | 93.69–96.03 | ||

| p-values | 0.0058 | 0.0467 | 0.9886 | 0.0954 | 0.3840 | 0.9546 | 0.0810 | - | - |

| Case | Record No. | Labels | Predict |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PTB-XL (all), ECG ID 9 | ‘NORM’, ‘SR’ | ‘ABQRS’, ‘SR’ |

| 2 | PTB-XL (diag.), ECG ID 299 | ‘ISC_’, ‘LAO/LAE’,’LVH’ | ‘IMI’,’ISC_’, ‘LVH’ |

| 3 | PTB-XL (sub-diag.), ECG ID 218 | ‘NORM’, ‘_AVB’ | ‘NORM’ |

| 4 | PTB-XL (super-diag.), ECG ID 38 | ‘NORM’ | ‘MI’ |

| 5 | PTB-XL (form), ECG ID 63 | ‘ABQRS’ | ‘ABQRS’, ‘PVC’ |

| 6 | PTB-XL (rhythm), ECG ID 347 | ‘AFLT’, ‘SR’ | ‘SR’ |

| 7 | CPSC2018, ECG ID 11 | ‘CLBBB’ | ‘AFIB’,’CLBBB’ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luo, K.; Huang, L.; He, H.; Chen, Y.; You, L.; Chen, S.; Chen, J.; Liu, C. Efficient and Interpretable ECG Abnormality Detection via a Lightweight DSCR-BiGRU-Attention Network with Demographic Fusion. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3882. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233882

Luo K, Huang L, He H, Chen Y, You L, Chen S, Chen J, Liu C. Efficient and Interpretable ECG Abnormality Detection via a Lightweight DSCR-BiGRU-Attention Network with Demographic Fusion. Mathematics. 2025; 13(23):3882. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233882

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuo, Kan, Longying Huang, Haixin He, Yu Chen, Lu You, Siluo Chen, Jian Chen, and Chengyu Liu. 2025. "Efficient and Interpretable ECG Abnormality Detection via a Lightweight DSCR-BiGRU-Attention Network with Demographic Fusion" Mathematics 13, no. 23: 3882. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233882

APA StyleLuo, K., Huang, L., He, H., Chen, Y., You, L., Chen, S., Chen, J., & Liu, C. (2025). Efficient and Interpretable ECG Abnormality Detection via a Lightweight DSCR-BiGRU-Attention Network with Demographic Fusion. Mathematics, 13(23), 3882. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233882