Abstract

Network covert channels embed secret data into legitimate traffic, but existing methods struggle to balance undetectability, robustness, and throughput. Application-independent channels at lower protocol layers are easily normalized or disrupted by network noise, while application-dependent streaming schemes rely on handcrafted traffic manipulations that fail to preserve the spatio-temporal dynamics of real encrypted flows and thus remain detectable by modern machine learning (ML)-based classifiers. Meanwhile, with the rapid adoption of HTTP/3, Quick UDP Internet Connections (QUIC) has become the dominant transport for streaming services, offering stable long-lived flows with rich spatio-temporal structure that create new opportunities for constructing resilient covert channels. In this paper, a QUIC streaming-based Covert Channel framework, QuicCC-SMD, is proposed that dynamically Shapes Multi-Dimensional traffic features to identify and exploit redundancy spaces for secret data embedding. QuicCC-SMD models the statistical and temporal dependencies of QUIC flows via Markov chain-based state representations and employs convex optimization to derive an optimal deformation matrix that maps source traffic to legitimate target distributions. Guided by this matrix, a packet-level modulation performs through packet padding, insertion, and delay operations under a periodic online optimization strategy. Evaluations on a real-world HTTP/3 over QUIC (HTTP/3-QUIC) dataset containing 18,000 samples across four video resolutions demonstrate that QuicCC-SMD achieves an average F1 score of 56% at a 1.5% embedding rate, improving detection resistance by at least 7% compared with three representative baselines.

Keywords:

network covert channel; streaming application; QUIC; spatio-temporal feature; convex optimization; packet manipulations MSC:

68M12

1. Introduction

With the rapid expansion of network applications and the exponential growth of Internet traffic, interception and data-leakage risks have increased sharply. As a result, secure data transmission has become a fundamental challenge in modern network security [1]. Existing protection mechanisms, including encryption, anonymization, and covert communication, offer different levels of privacy [2]. While encryption ensures data confidentiality and anonymization conceals user identity, both fail to hide the existence of communication [3,4]. Network covert channels address this gap by embedding secret data into redundant components of legitimate traffic to enable covert communication. However, such embedding inevitably alters traffic patterns, leaving covert channels vulnerable to detection and creating a persistent trade-off among undetectability, throughput, and practical deployability [5].

Based on their construction mechanisms, network covert channels can be broadly classified into application-independent and application-dependent covert channels [6]. Application-independent covert channels are realized within lower-layer network protocols and remain decoupled from upper-layer application semantics. They mainly include covert storage channels (CSCs) and covert timing channels (CTCs) [7]. CSCs embed secret data into reserved or unused protocol fields, providing stable transmission but remaining highly susceptible to protocol conformity checks and normalization techniques [8]. In contrast, CTCs encode secret data by modulating temporal features such as inter-packet intervals or packet ordering [9]. Although this approach avoids modifying packet content directly, it is highly sensitive to network jitter and congestion. Random delay variations in dynamic environments further reduce its robustness and limit its practical applicability [10].

In contrast, application-dependent covert channels exploit specific application services or behavioral patterns as carriers for covert communication. Among them, streaming-based covert channels have become the most representative subclass [11]. Multimedia streaming applications naturally produce high-volume, temporally correlated traffic, offering a plausible cover for embedding secret data. Existing approaches often insert or replace video frames with covert information before application-layer encryption, maintaining concealment from protocol-level inspection [12,13,14]. However, such methods are typically tailored to individual applications, with embedding mechanisms manually designed around specific redundant spaces to maximize throughput and stealth. This heavy dependence on application versions, runtime environments, and privileged system access greatly limits their scalability and practical deployment. Moreover, these coarse-grained manipulations fail to preserve the spatio-temporal patterns of legitimate traffic. They introduce measurable deviations that are easily captured by modern machine learning-based traffic classifiers, reducing stealthiness and reliability [15].

These limitations reveal a critical research gap. While application-dependent streaming-based covert channels can achieve higher throughput and undetectability than application-independent methods, their designs remain fragile and overly customized. Once an application is updated or its streaming behavior changes, the covert mechanism often becomes invalid. Therefore, a more general and adaptive covert channel framework is required, one capable of operating within modern encrypted traffic while faithfully preserving the inherent statistical and temporal characteristics of legitimate streams.

With the widespread adoption of HTTP/3, QUIC-based streaming traffic provides a strong foundation for covert channel construction. Unlike TLS/TCP-based streaming, QUIC encrypts nearly all header fields, allowing payload modifications without violating protocol semantics. Its UDP-based, connection-independent design further ensures that each packet can be manipulated individually without affecting session state. These properties collectively make QUIC streaming an ideal substrate for covert communication, enabling secret data to be embedded while maintaining realistic traffic patterns and achieving resilient, high-capacity covert transmission under real-world network conditions. Recent work, such as QuicCourier [6], has taken an initial step toward exploiting QUIC traffic dynamics by modeling revisit-driven behaviors in website browsing [16]. However, its applicability remains confined to event-driven web traffic and does not extend to the widely adopted and rapidly growing domain of multimedia streaming, where long-lived sessions and strongly temporally correlated burst patterns dominate. Other approaches based on general generative or adversarial learning attempt to approximate target traffic distributions, but they typically fail to preserve directional and temporal dependencies across flows [17,18], leading to detectable inconsistencies under modern traffic classifiers.

In this paper, a QUIC streaming-based covert channel framework, QuicCC-SMD, is proposed to identify and exploit redundancy spaces within legitimate traffic for secret data embedding through multi-dimensional feature shaping. QuicCC-SMD introduces a dynamic embedding mechanism that operates directly within encrypted QUIC traffic, modeling streaming dynamics through a Markov chain-based representation to capture both statistical and temporal dependencies of packet flows. Building upon this representation, a deformation matrix optimization process formulates secret data embedding as a convex optimization problem, minimizing packet manipulation cost while preserving the legitimate feature consistency of target traffic. The optimized transformation is then applied through real-time packet manipulations guided by a periodic online strategy, enabling the system to adaptively align its embedding behavior with evolving streaming characteristics.

The main contribution of this study can be outlined as follows:

- (1)

- A QUIC streaming-based covert channel framework QuicCC-SMD is developed to dynamically embed secret data by shaping multi-dimensional traffic features while maintaining the spatio-temporal characteristics of legitimate flows. It constructs Markov chain-based spatio-temporal representations to capture both statistical and temporal dependencies of streaming flows, derives embedding guidance through a deformation matrix, and performs packet-level feature modulation via a periodic online optimization strategy. This unified framework achieves adaptive and stealthy covert communication by maintaining the statistical fidelity and temporal dynamics of legitimate QUIC traffic.

- (2)

- A convex optimization-based deformation mechanism is formulated to express the embedding process as a constrained optimization problem, through which the optimal transformation between source and target traffic distributions is derived. By minimizing packet manipulation cost under normalization and non-negativity constraints, it can produce a sparse deformation matrix that efficiently preserves legitimate feature consistency while reducing embedding distortion, enabling low-cost and high-undetectability covert data transmission.

- (3)

- A comprehensive evaluation is conducted on a real-world HTTP/3-QUIC streaming dataset comprising four video resolutions and over 18,000 traffic samples to assess the performance of the proposed framework. Experimental results show that QuicCC-SMD consistently outperforms two representative baselines, achieving an average F1 score (the harmonic mean of precision and recall) of 56% against three state-of-the-art traffic classifiers at a 1.5% embedding rate. This corresponds to an improvement of at least 7% in detection resistance compared with the second-best baseline.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related work on existing covert channel schemes. Section 3 introduces the adversary model and presents the overall architecture of QuicCC-SMD. Section 4 describes the design and workflow of the proposed system. Section 5 presents experimental results and performance analysis. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

This section summarizes existing studies on network covert channels, which can be divided into application-independent and application-dependent approaches. The former designs generic embedding schemes across protocols, whereas the latter leverages application-specific behaviors for optimized covert communication.

2.1. Application-Independent Covert Channel

Application-independent covert channels primarily exploit the redundancy or timing characteristics of network protocols without depending on specific applications. They can be broadly categorized into covert storage channels and covert timing channels.

Covert storage channels achieve covert communication by embedding secret data directly into protocol headers or payload fields. Depending on the protocol layer, CSCs can be implemented at the application, transport, or network layer. At the application layer, secret data is often inserted into optional or unused fields of protocols such as HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP), Real-time Transport Control Protocol (RTCP), Domain Name System (DNS), and File Transfer Protocol (FTP). Bistarelli et al. [19] modulated HTTP request headers to embed data within specific header fields. Semushin et al. [20] exploited the order-insensitivity of HTTP header fields to encode secret data through reordering. Kwecka [21] utilized whitespace manipulation in HTTP headers, interpreting tabs and spaces as binary symbols. For other application protocols, Zhang et al. [22] embedded data into RTCP jitter and sequence number fields, Nussbaum [23] transmitted secret messages through DNS queries and responses, and Zou et al. [24] modulated the number of FTP No Operation (NOOP) commands during idle periods. At the transport layer, CSCs are commonly implemented in Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), taking advantage of its redundancy and high frequency. Bistarelli et al. [25] encoded text characters within TCP initial sequence numbers and used the identification field for message verification, employing error correction to handle packet loss. Giffin et al. [26] embedded data into the TCP timestamp field, which provides good concealment as the field is used for flow control rather than protocol correctness. At the network layer, IPv4 and IPv6 fields can serve as covert carriers. Zander et al. [27] encoded secret data into the Time To Live (TTL) field of IPv4 packets, while Mavani et al. [28] constructed a covert channel through the IPv6 DNS-over-HTTPS (DoH) field, which is only processed at the destination and thus remains opaque to intermediate routers.

Although CSCs are relatively stable, their dependence on protocol field redundancy and non-standard field usage makes them highly detectable. Cabaj et al. [29] demonstrated that field distribution modeling can effectively identify abnormal HTTP POST headers with high accuracy and low false positives. Furthermore, with the widespread adoption of Transport Layer Security (TLS)/Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) encryption and the introduction of QUIC, the transport layer foundation of HTTP/3, CSCs have become largely impractical. QUIC encrypts nearly all header fields and minimizes redundancy, eliminating the unencrypted spaces required for covert channel construction.

In another, covert timing channels encode secret data by manipulating temporal characteristics of packet transmissions, such as inter-packet intervals, transmission rates, packet ordering, or retransmissions. Because they do not modify protocol contents, CTCs are compatible with various network packets and can bypass deep packet inspection techniques. Inter-packet interval modulation is the most common approach. Cabuk et al. [30] proposed the classical covert timing channel, where the presence or absence of packets in pre-defined time slots encodes binary bits. In [31], a time–replay channel is introduced that records timing distributions from normal traffic and replays them to minimize statistical deviation. In transmission rate modulation, secret messages are encoded by varying traffic throughput. Li et al. [32] exploited switch-level performance fluctuations to influence the transmission rate of unrelated flows, indirectly transmitting secret data. Packet-order modulation alters packet sequences to encode secret data. Tahir et al. [33] proposed Sneak-Peek, a high-speed covert channel suitable for data centers, where queue states and transmission delays represent encoded secret data. Retransmission-based channels use deliberately retransmitted packets as carriers. Mazurczyk et al. [34] introduced retransmission steganography, where receivers intentionally omit acknowledgments to trigger retransmissions carrying covert data.

Despite their flexibility, CTCs are highly sensitive to network noise, delay, and jitter [35]. Wu et al. [36] empirically demonstrated that bit error rates vary significantly across network conditions, increasing sharply in high-latency or jittered environments. Moreover, timing-modulated sequences exhibit detectable regularities distinct from natural network randomness. Stillman et al. [37] applied machine learning to timing features, achieving high detection accuracy for timing channels, while Wu et al. further showed that even advanced statistical-fitting methods yield low capacity and limited robustness.

2.2. Application-Dependent Covert Channel

With the dominance of multimedia applications, application-dependent covert channels have gained increasing attention. These channels leverage the inherent redundancy of application-layer media streams, such as audio and video, to embed secret data, rather than manipulating protocol headers or timing alone. Typical examples include Skype-based and YouTube-based covert communication schemes. Specifically, Facet [38] was designed for censorship circumvention by converting restricted web content into Skype video sessions. It coordinated clients and servers to transmit low-resolution video streams that appeared as normal Skype calls. CovertCast [12] extended this concept to multi-client scenarios, broadcasting encoded data via YouTube live streams, where clients decode secret messages from video frames while maintaining traffic indistinguishability from ordinary viewers. DeltaShaper [13] generalized the approach to arbitrary TCP/IP traffic, embedding data into video frames during Skype calls to support bidirectional communication. Although streaming-based channels effectively mimic video traffic patterns and evade traditional detection, their fixed encoding parameters deviate from the adaptive bitrate dynamics of genuine video streams. Recent deep learning-based detectors have exploited these discrepancies to achieve near-perfect detection. Barradas et al. [14] introduced an entropy-based method analyzing packet-size distributions, inter-arrival times, and burstiness to distinguish covert streams. Chen et al. [39] further combined convolutional neural network (CNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) architectures to capture temporal dependencies, achieving detection rates exceeding 98% across Facet, CovertCast, and DeltaShaper.

More recently, covert channels have been extended to diverse application domains. Mao et al. [40] proposed a video comment-based channel that modifies the timing of online bullet comments to encode hidden data, while Xue et al. [41] utilized the push notification mechanism in mobile apps for direct payload embedding. Sun et al. [42] introduced Telepath, which replaces redundant in-game state messages in Minecraft with covert information for real-time communication. From a design perspective, these approaches reveal a clear trend toward exploiting application-specific semantics and context-aware redundancy for enhanced throughput. However, they remain tightly coupled to specific codec or application implementations that constrain portability and stability. Any modification in the underlying application logic can invalidate the covert mapping. Consequently, current application-dependent covert channels generally exhibit limited adaptability and robustness, motivating the need for frameworks that can generalize across streaming contexts while maintaining realistic spatio-temporal fidelity.

3. System Design

This section introduces the design of QuicCC-SMD, starting from the adversary model that defines the threat assumptions, followed by an overview of the system architecture that enable covert embedding within QUIC streaming flows.

3.1. Adversary Model

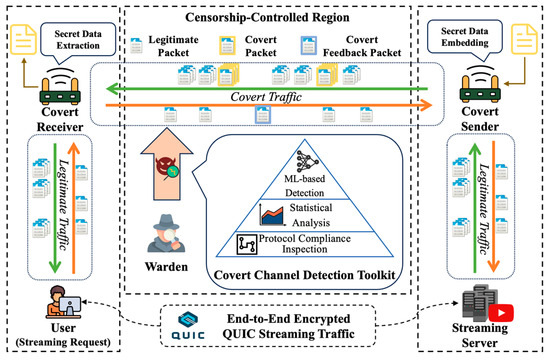

As illustrated in Figure 1, a canonical adversary model for network covert channels is considered, where the communication path between a covert sender and a covert receiver traverses a censorship-controlled region monitored by a warden [43,44]. When a user requests multimedia content from a streaming service, a QUIC streaming connection is established between the client and the server. Leveraging this legitimate connection, the covert sender embeds secret data into downlink streaming traffic, while the covert receiver extracts the secret data and embeds feedback information to enhance reliability.

Figure 1.

The adversary model of the proposed covert channel.

The warden is assumed to have maximal passive observation capability within the censorship-controlled region [45]. It can capture, inspect, and analyze all traffic flows using a comprehensive detection toolkit that includes protocol compliance inspection, statistical feature analysis, and advanced machine learning-based detection. However, as a passive adversary, the warden cannot alter or delay packets without disrupting normal Internet operations, nor can it decrypt payloads protected by end-to-end encryption. Although unable to access the plaintext of QUIC packets, the warden can still exploit observable side-channel information, such as packet length, burst patterns, and inter-packet delay, to perform statistical analysis or train traffic classifiers to detect covert activities.

Under such a powerful adversary, covert channels face stringent design constraints. The secret data embedding process must not disrupt the normal protocol state machine or alter the observable statistical properties of legitimate traffic, as any detectable deviation may expose the covert communication to the warden. Furthermore, covert nodes must intercept, modify, and forward legitimate packets in a manner that preserves protocol integrity. Any improperly embedded bytes that cause parsing errors or trigger retransmissions in the streaming application may lead to abnormal behaviors that are easily observable by the warden. Therefore, the embedding mechanism must ensure that both the semantic integrity and behavioral dynamics of genuine QUIC streams remain indistinguishable from normal communication.

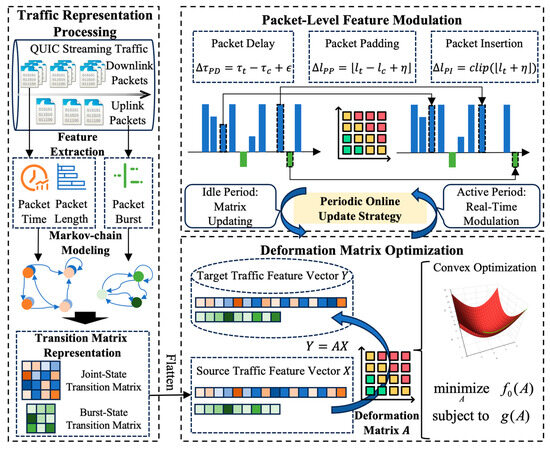

3.2. Workflow of QuicCC-SMD

As illustrated in Figure 2, QuicCC-SMD is a QUIC streaming covert channel framework that shapes multi-dimensional traffic features to locate and exploit redundancy for secret data embedding. The framework comprises three modules: (1) traffic representation processing, which models spatio-temporal flow features with Markov chains; (2) deformation matrix optimization, which formulates embedding as a convex optimization problem that minimizes operational cost while preserving statistical fidelity; and (3) packet-level feature modulation, which implements the optimized policy via concrete packet operations with a periodic online update strategy. Together these modules enable efficient embedding that retains the statistical behavior of legitimate QUIC streaming traffic.

Figure 2.

Overview of QuicCC-SMD.

The traffic representation module captures both statistical and temporal dynamics of QUIC streams as transition probability matrices. Because downlink packets carry the bulk of multimedia content, whereas uplink packets are dominated by bursty control or request traffic [46], a joint-state transition matrix is constructed for downlink packet length and inter-packet delay to capture spatio-temporal dependencies, and a burst-state transition matrix is constructed for uplink burst dynamics to represent transmission behavior. Using these source and target transition matrices, the deformation matrix optimization module computes a high-dimensional deformation matrix that maps source transitions to target transitions. The optimization minimizes a transformation cost over the joint state space, thereby reducing required downlink packet operations and uplink embedding overhead while meeting embedding capacity constraints.

Finally, the packet-level modulation module applies the optimized mapping in real time: the deformation matrix is updated during idle intervals and applied during active periods to guide packet manipulations. Guided by probabilistic mappings, the system executes three packet operations, including packet delay, packet padding, and packet insertion, to adjust timing, sizes, and injected packets so that the resulting flow preserves the original spatio-temporal statistics and remains stealthy. Detailed algorithms and implementation are presented in Section 4.

4. Secret Data Embedding Process of QuicCC-SMD

The embedding process of QuicCC-SMD integrates three sequential modules: traffic representation, deformation matrix optimization, and packet-level modulation. These modules collaboratively extract flow dynamics, optimize covert embedding mappings, and guide them into packet-level adjustments to ensure efficiency and undetectability.

4.1. Traffic Representation Processing

To accurately model the statistical and temporal dynamics of QUIC streaming traffic for covert data embedding, QuicCC-SMD employs a Markov chain-based transition probability matrix to characterize the evolution of traffic features over time. The transition matrix describes the likelihood of transitioning between discrete states, thereby capturing both packet-level temporal dependencies and statistical feature variations.

Formally, let the state space of a discrete-time Markov chain be , where denotes the total number of states. The probability of transitioning from state to state within one time step is defined as:

The corresponding transition matrix satisfies and [47]. In QuicCC-SMD, two types of Markov-based transition matrices are constructed: a joint-state transition matrix for downlink traffic to model inter-packet delay and packet-length dependencies, and a burst-state transition matrix for uplink traffic to characterize burst transmission dynamics.

4.1.1. Joint-State Transition Matrix Construction

Since packet length and inter-packet delay are both strongly correlated with the streaming transmission process, a joint-state transition matrix is constructed to jointly characterize their spatio-temporal dependencies. This matrix captures the evolution of traffic dynamics by modeling the probabilistic transitions between discrete joint states defined by these two features.

To obtain the packet-length feature states, a kernel density estimation (KDE) function is applied to identify dominant modes in the empirical packet-length distribution. These modes are then used to partition the value range into discrete states, forming the set , where represents the -th packet length state. The discretization thresholds are determined by minimizing the area difference between each segment and a uniform probability mass target [48]:

For the inter-packet delay, a K-Means clustering algorithm is employed to discretize the continuous delay sequence into temporal states by minimizing intra-cluster variance [49]:

where is the inter-packet delay of the -th packet, and denotes the set of cluster centroids. The resulting discrete delay state set is .

Each packet is mapped to a joint state , and the overall joint state space is with cardinality . It enables the Markov model to characterize dependencies across packet length and timing dimensions. Given a QUIC streaming flow consisting of packets, the transition frequency from states to state is computed as

where is the indicator function. Finally, the joint-state transition probability matrix is then obtained by row-normalizing the transition frequencies [50]:

The resulting matrix provides a complete probabilistic representation of the coupled evolution of packet-length and inter-packet-delay states in QUIC streaming flows.

4.1.2. Burst-State Transition Matrix Construction

The burst-size feature, defined as the number of packets transmitted consecutively in the same direction, serves as a discrete characteristic reflecting the uplink traffic behavior and responsiveness of QUIC streams. Unlike inter-packet delay, burst size is inherently discrete and can therefore be modeled directly without additional discretization.

Formally, let denote the set of observed burst sizes in the uplink traffic, where represents the number of packets in the -th burst, and is the total number of distinct burst states. For an uplink flow consisting of bursts, each burst is mapped to a state . The transition frequency from state to state is computed as:

The burst-state transition probability matrix is then obtained by row normalization:

where each element represents the probability of transitioning from burst state to state . The resulting matrix characterizes the temporal evolution patterns of uplink burst behavior across consecutive transmission intervals. This representation complements the joint-state transition matrix of downlink traffic, jointly providing a multi-dimensional probabilistic model of QUIC streaming dynamics for subsequent deformation and embedding optimization.

4.2. Deformation Matrix Optimization

To extend traffic transformation from a static mapping to a dynamic modeling process, QuicCC-SMD introduces a deformation matrix optimization framework that independently optimizes the deformation process for downlink and uplink traffic. In this formulation, the source traffic is represented by a state transition matrix , where each element denotes the probability of transitioning from state to . Similarly, the target traffic is represented by .

To map the source transition distribution into that of the target, a deformation matrix is introduced to describe probabilistic mappings between their transition spaces. For computational consistency, both transition matrices are vectorized:

The deformation process satisfies . Expanding this formulation yields linear equations, expressed as , subject to the normalization constraint .

The above formulation defines an underdetermined mapping problem with infinitely many feasible solutions. Hence, the optimal deformation matrix is obtained by solving the following constrained convex optimization problem:

where denotes the deformation cost, and represents the structural constraints ensuring normalization, non-negativity, and embedding feasibility.

4.2.1. Joint-State Modeling

For the downlink flow, which carries streaming content and serves as the main carrier for covert data, the objective is to minimize packet-operation overhead while guaranteeing a minimum embedding throughput. Each element represents the probability of mapping a source transition from state to to a target transition from state to . The expected operation cost is:

where denotes the transition probability in the source process, and is an indicator function that equals 1 when the transition changes state. This term penalizes non-diagonal mappings, which correspond to packet manipulations.

To guarantee a minimum covert data capacity, an additional constraint is imposed to ensure sufficient embedding throughput:

where is the payload size of covert packets carrying secret data, typically set to the maximum transmission unit (MTU) length as downlink QUIC streams predominantly transmit full-sized packets. and denote the inter-packet delay states, and specifies the minimum required embedding volume.

Combining these objectives, the downlink joint-state optimization problem is formulated as:

Here, is the transition-mapping matrix to be optimized and represents the expected packet-operation cost, penalizing any mapping that alters the original state transition. The first equality constraint ensures that the transformed transition probabilities in the target flow remain normalized and consistent with legitimate traffic statistics, the second and third constraints enforce valid stochastic mappings (rows summing to one and non-negativity), and the final inequality ensures a minimum embedding throughput. This convex optimization formulation explicitly balances two competing objectives, including minimizing manipulation cost and maintaining sufficient data-embedding capacity, under probabilistic transition constraints.

4.2.2. Burst-State Modeling

For uplink traffic, composed primarily of control and QUIC acknowledgement (ACK) packets, the objective is to minimize the number of inserted feedback packets while maintaining statistical consistency with legitimate traffic patterns. Each element represents the probability of mapping a source burst transition from state to state to a target transition from state to state . The cost function is:

where denotes the transition probability of the source burst process, and represents the length of a standard QUIC ACK packet. When the target burst size is smaller than the current burst , additional feedback packets of size are inserted to align with the legitimate target burst pattern. The corresponding uplink burst-state optimization problem is:

Analogous to Equation (12), this optimization is formulated to minimize the expected number of inserted feedback packets while maintaining probabilistic consistency between the source burst-state transitions and their target counterparts.

4.2.3. ADMM-Based Optimization Solving

Both the source and target transition matrices are inherently sparse, as most state transitions in real QUIC streaming traffic exhibit near-zero probabilities [51]. Thus, the deformation process leads to a high-dimensional sparse optimization. To efficiently solve it, the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (ADMM) [52] is adopted for its scalability in constrained convex problems:

where is the penalty parameter, is the dual variable, and denotes the feasible set defined by normalization and non-negativity constraints.

In practice, convergence to a local optimum is considered acceptable when the relative reconstruction error satisfies , where denotes the Frobenius norm of the reconstruction residual between the target transition matrix and the transformed matrix , and is a small tolerance parameter controlling convergence precision. The optimization process terminates early when the increment in the cost function falls below 10%, ensuring computational efficiency without sacrificing solution accuracy. Additionally, a dynamic pruning mechanism is employed to suppress negligible transition paths. Edges with prior probabilities below are discarded during preprocessing, and low-magnitude entries in are periodically pruned every ten ADMM iterations to maintain sparsity and accelerate convergence.

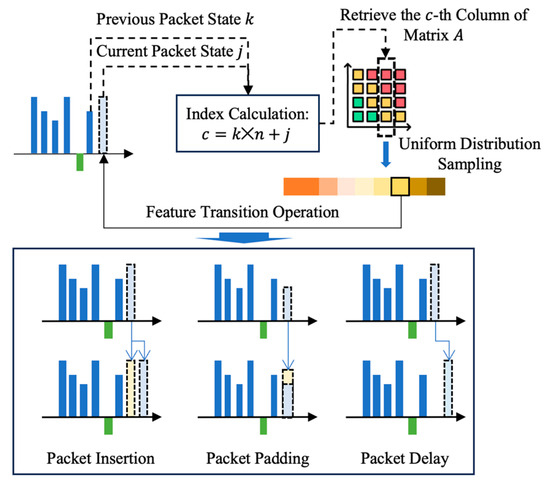

4.3. Packet-Level Feature Modulation

Leveraging the optimized deformation matrix , QuicCC-SMD dynamically adjusts state transitions at the packet level to embed secret data while preserving the statistical properties of legitimate QUIC streaming traffic. When a source packet arrives, the modulation decision depends on the relationship between the current and previous states. Specifically, if the previous packet is in state , the current transition pair is in state . The corresponding column of the deformation matrix, is extracted, and a target transition pair is sampled according to its cumulative probability distribution. The selected pair then guides the subsequent packet modulation process, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Packet-level modulation workflow of QuicCC-SMD.

For downlink flows, QuicCC-SMD jointly modulates the inter-packet delay and packet length to preserve their spatio-temporal dependency. If the current delay is shorter than the target delay (i.e., ), an additional delay is introduced:

where is zero-mean Gaussian jitter and is its standard deviation. When , a covert packet with payload length is inserted to preserve the statistical delay distribution, represented as:

where is bounded uniform noise with half-width and MTU is the maximum transmission unit. For packet length modulation, when the current length is smaller than the target length , the packet is padded by additional bytes, ensuring statistical continuity in the packet-size distribution and reducing detectability.

For uplink flows, modulation targets the burst-size feature , which represents the number of packets transmitted consecutively within the same burst. When the current burst size , the burst is extended by introducing a delay:

where is the preset burst duration. Conversely, when , a covert packet with a fixed ACK-size payload is inserted to segment the excessive burst. After each transmission, the burst counter is updated as , and reset to whenever a packet is inserted or a new burst begins. This adaptive burst management preserves the statistical regularity of legitimate QUIC request patterns while maintaining the functionality of the covert feedback channel.

To synchronize embedding with traffic dynamics, QuicCC-SMD incorporates a periodic online update strategy that alternates between active and idle phases. During active phases, the system performs real-time packet modulation while simultaneously collecting packet sequences to estimate the source transition matrix . The previously optimized deformation matrix is applied in real time to guide packet-level transformations. During idle phases, ADMM optimization is invoked to update the deformation matrix based on the most recent transition statistics, which is then applied in the subsequent active phase. Through this continuous adaptation mechanism, QuicCC-SMD maintains real-time synchronization between the embedding process and evolving traffic dynamics, achieving efficient covert embedding while preserving statistical fidelity and strong resistance to detection.

5. Experiments

This section presents the experimental evaluation of QuicCC-SMD to validate the effectiveness of the proposed framework. The experiments are organized to assess how the modules introduced in Section 4 collectively support covert communication. Specifically, the evaluation contains: parameter selection for the Markov-based traffic representation and optimization model, transmission efficiency achieved through deformation matrix-guided packet manipulation, undetectability in terms of preserving spatio-temporal statistical consistency, reliability under real-world network conditions, and a final discussion analyzing the overall effectiveness of the system.

5.1. Experimental Setup

5.1.1. Dataset

To evaluate the effectiveness of QuicCC-SMD, a real-world HTTP/3-QUIC streaming dataset was collected from YouTube using a QuicCC-SMD prototype deployed in a controlled laboratory environment. The testbed consists of a Windows 10 client and two in-path routers acting as covert participant for secret data transmission. The client continuously requests and plays streaming content from various YouTube webpages with different video resolutions (360 p, 480 p, 720 p, and 1080 p), ensuring comprehensive coverage of diverse spatio-temporal characteristics inherent to multimedia streaming traffic.

For each resolution, traffic corresponding to the first 30 s of 4500 recommended videos was captured to construct a balanced and representative dataset. To minimize manual intervention and maintain acquisition consistency, the data collection process was fully automated using Python scripts. Specifically, PyAutoGUI (version: 0.9.54) and Selenium (version: 4.28.1) were employed to simulate user interactions and control browser navigation. Browser cache and cookies were cleared before each session to prevent caching bias and ensure independent samples.

The collected dataset was divided as follows: 1500 samples per resolution were used as target traffic to extract features for deformation matrix construction, 1500 samples were used as source traffic for secret data embedding to generate covert traffic, and another 1500 samples were retained as legitimate traffic for reference and comparison. The covert and legitimate samples were utilized for comparative statistical and detection evaluation. To ensure robustness, all experiments were repeated across 10 random dataset splits, and the averaged results were reported. Unless otherwise specified, all subsequent experiments are conducted on the mixed dataset combining samples from all resolutions to provide comprehensive performance evaluation. The overall composition of the dataset is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Composition of traffic dataset used for QuicCC-SMD evaluation.

5.1.2. Baselines for Performance Evaluation

To comprehensively evaluate QuicCC-SMD, representative ML-based traffic classifiers are used to assess undetectability, and baseline embedding schemes are implemented to compare embedding efficiency and robustness.

- (1)

- Traffic Classifier: Five representative classifiers are adopted to evaluate the detectability of covert traffic: AppScanner [53], Deep Fingerprinting (DF) [54], MTL [55], TrafficFormer [56], and SmartDetector [57].

AppScanner is a random forest-based classifier that performs traffic identification using statistical features extracted from packet length sequences. It computes a total of 54 features, including the maximum, minimum, mean, and variance of packet sizes from uplink, downlink, and bidirectional flows.

DF is a CNN-based traffic classifier that captures temporal dependencies and hierarchical spatial patterns in packet sequences. DF consists of four convolutional blocks and two fully connected layers. In our implementation, both packet length and inter-packet delay sequences are used as parallel inputs, concatenated before the softmax layer to enhance joint spatio-temporal feature learning.

MTL is an autoencoder-based traffic classifier that enhances feature robustness through noise-injected reconstruction. It employs a two-layer denoising autoencoder to learn latent representations resilient to heterogeneous and noisy network conditions. The encoded latent features are then fed into a support vector machine (SVM) for final classification.

TrafficFormer is a pre-training traffic classification model that learns robust traffic representations through masked burst modeling and same-origin burst prediction tasks. It converts packet sequences into tokenized representations and adopts a bidirectional encoder representation from Transformers (BERT)-based deep neural architecture to capture both semantic and sequential dependencies within traffic flows, enabling efficient and accurate traffic identification.

SmartDetector is a contrastive learning-driven encrypted traffic detection framework. It constructs a semantic attribute matrix using packet length, inter-packet delay, and direction features, and employs self-supervised contrastive mechanism to learn discriminative representations. Additionally, SmartDetector introduces obfuscated samples for data augmentation to enhance robustness and classification performance.

- (2)

- Covert Embedding Schemes: To evaluate the effectiveness of the utilized secret data embedding algorithm, three embedding schemes are implemented for comparison: uniform distribution embedding (UDE), random swap embedding (RSE), and QuicCourier.

UDE performs packet insertion at a fixed rate, embedding secret data uniformly across the streaming flow. In the downlink packets, inserted covert packets adopt the MTU-sized payload length, while in the uplink packets, they mimic typical ACK-sized packets. This method leverages natural redundancy to achieve secret data embedding.

RSE introduces stochasticity by using pseudo-random generation to determine both the timing and location of packet insertion or padding, as well as the number of bytes embedded per packet. By dynamically perturbing traffic patterns, RSE reduces deterministic artifacts and increases secret data embedding randomness.

QuicCourier constructs traffic representation based on the run-length sequence of consecutive MTU-sized packets, capturing the alternation between MTU and non-MTU packets to model dynamics. It employs a custom WebSpare algorithm to decompose each flow into intrinsic and external dynamic components, enabling the generation of representative traffic templates that guide covert data embedding. During embedding, QuicCourier determines whether to insert or modify packets according to the generated template, aligning covert operations with legitimate traffic fluctuations.

All experiments are conducted on a workstation running Ubuntu 20.04 LTS, equipped with an Intel Core i9-14900KF CPU, 64 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU with 24 GB of memory. The implementation is developed in Python 3.8.10.

5.1.3. Performance Metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed covert communication framework, multiple complementary metrics are employed, covering transmission efficiency, statistical similarity, detection resistance, and reliability.

- (1)

- Transmission Efficiency Metrics: Covert throughput quantifies a covert channel’s capability to transmit secret data. Three complementary metrics, including average operations per packet (), embedding rate (), and transmission rate (), are used to jointly assess embedding efficiency and carrier utilization.

The measures the operational cost of embedding, defined as:

where is the number of manipulations applied to the -th packet and is the total number of packets. A lower indicates a more efficient and lightweight secret data embedding process, implying lower implementation overhead and reduced risk of exposure.

The measures the proportion of carrier capacity used for secret embedding:

where and denote the number of transmitted secret bits and total carrier bits, respectively. A higher improves covert throughput but increases detectability.

The reflects the absolute data throughput:

where is the total transmission duration. (in bps) indicates the effective capacity and responsiveness of the covert channel.

- (2)

- Statistical Similarity Metrics: Statistical analysis is a fundamental approach for covert channel detection since embedding inevitably distorts the legitimate traffic distribution. Two complementary measures, including Earth Mover’s Distance (EMD) [58] and Hellinger Distance (HD) [59], are adopted to quantify distributional differences between covert and legitimate traffic.

EMD evaluates the minimum effort required to transform one probability distribution into another :

where is the absolute feature difference, is the set of joint distributions with marginals and , and denotes the transported probability mass. Larger EMD values indicate greater deviation in global flow behavior.

For discretized features, the HD is given by:

where and are normalized probabilities of the -th bin for covert and legitimate traffic. HD captures local deviations, particularly in rare or low-probability regions. Together, EMD reflects global distributional shifts, while HD highlights localized distortions, providing a comprehensive view of statistical similarity.

- (3)

- Classifier-Based Detection Metrics: To assess detectability directly, a feature-based classifier is used to distinguish covert traffic from legitimate flows. Detection performance is measured using precision, recall, and the F1 score:

- (4)

- Covert Reliability Metric: Reliability measures a covert channel’s ability to maintain stable communication under real-world network disturbances such as noise, packet loss, and delay jitter. The message success rate () quantifies this as:

To account for retransmissions and header overhead, the effective embedding rate () is introduced to evaluate the ratio between successfully delivered secret data and the total transmitted secret data:

where is the total transmitted secret bits including retransmission and protocol header overhead.

5.2. The Selection of Parameters

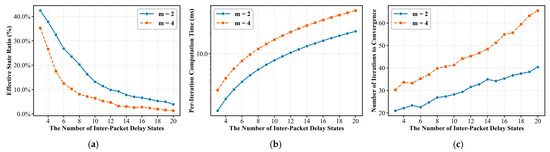

This section investigates how the dimensionality of the joint state space influences the performance of the ADMM-based optimization algorithm. The state-space dimension defines the granularity of Markov chain modeling, lower dimensions may overlook subtle traffic dynamics, whereas excessively high dimensions increase computational complexity and risk overfitting. Due to the inherent sparsity of traffic transitions, the number of effective transition probabilities is substantially smaller in practice.

To determine an appropriate configuration, the number of packet length states is set to . When , packet lengths are coarsely categorized into MTU-sized and non MTU-sized packets, with the latter represented by their mean value. When , non MTU-sized packets are further divided into three clusters corresponding to local maxima in the empirical length distribution. Similarly, the number of inter-packet delay states is varied to construct joint state spaces of different dimensions. For each configuration, the ADMM optimization algorithm is trained, and its matrix sparsity, average iteration runtime, and convergence iteration count are evaluated. The experimental results are summarized in Figure 4a–c.

Figure 4.

Parameter Analysis of different settings: (a) Effective state ratio; (b) Computation time per iteration; (c) Number of iterations to convergence.

Figure 4a demonstrates that all transition matrices exhibit strong sparsity. When , the proportion of non-zero elements is approximately 37.8%, which rapidly decreases as the state-space dimension increases, dropping to 1.33% at . These results empirically confirm that the transition probability matrix of QUIC streaming traffic is inherently sparse, validating the feasibility of structured sparsity optimization in later stages.

Figure 4b depicts the per-iteration runtime of the ADMM algorithm across different dimensions. For easier visualization, we use a log scale. The runtime increases superlinearly with the state-space size: each iteration requires about 2.2 ms for and roughly 31 ms for . It is known that the effective computation cost grows faster due to iterative optimization overheads and sparse matrix operations.

Figure 4c shows the convergence behavior of ADMM. The required iteration count generally rises with increasing dimensionality, low-dimensional configurations typically converge within 30 iterations, whereas high-dimensional ones demand over 50. This trend reflects the growing complexity of the optimization landscape in higher-dimensional spaces.

Balancing matrix sparsity and computational efficiency, the configuration is selected as the optimal setup. It achieves a favorable trade-off between modeling precision and runtime, with an average convergence time of 0.6 s, per-iteration runtime of ≈16 ms, and ≈41 iterations to converge. Under this configuration, only 6% of matrix elements remain non-zero, confirming the high sparsity of the problem and reinforcing the effectiveness of sparse optimization techniques.

5.3. Transmission Efficiency Analysis

To evaluate the transmission efficiency of QuicCC-SMD, this section examines the embedding rate , transmission rate , and the corresponding operational cost measured by the average operations per packet .

- (1)

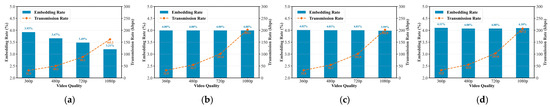

- Embedding Rate and Transmission Rate: The embedding rate of QuicCC-SMD is determined by both the deformation matrix-guided transition operations and the embedding threshold applied during convex optimization. As these factors interact with the statistical characteristics of the carrier stream, the actual varies across different types of video traffic. To evaluate this behavior, four YouTube video resolutions (360 p, 480 p, 720 p, and 1080 p) are selected as representative streaming scenarios, with the embedding threshold configured as . The results are shown in Figure 5 compared with other three schemes.

Figure 5. Embedding rate and transmission rate under different YouTube video resolutions: (a) QuicCC-SMD; (b) UDE; (c) RSE; (d) QuicCourier.

Figure 5. Embedding rate and transmission rate under different YouTube video resolutions: (a) QuicCC-SMD; (b) UDE; (c) RSE; (d) QuicCourier.

As illustrated in Figure 5a, the of QuicCC-SMD gradually decreases as video quality increases, with average values of 3.93%, 3.67%, 3.49%, and 3.21% for 360 p, 480 p, 720 p, and 1080 p, respectively. In contrast, the other baseline schemes maintain an embedding rate inherently close to 4%, because they apply fixed-rate or stochastic packet insertions without incorporating an embedding rate constraint. QuicCC-SMD, however, enforces the embedding threshold as a constraint within its optimization framework, allowing the deformation matrix to reduce embedding operations when redundancy becomes insufficient.

The downward trend observed for QuicCC-SMD is expected: higher-resolution videos generate more homogeneous traffic patterns, where packet sizes converge tightly around the MTU, leaving fewer opportunities for safe embedding. Conversely, the transmission rate increases significantly with video resolution, reaching approximately 31.3 kbps, 50.2 kbps, 88.1 kbps, and 162.2 kbps. Higher-resolution streams produce denser packet sequences and greater bandwidth utilization, enabling larger covert payload delivery even under lower .

Overall, these results show that QuicCC-SMD maintains stable embedding efficiency across diverse streaming conditions while effectively exploiting the higher traffic volume of high-resolution video to achieve increased covert throughput. This confirms that the method scales reliably with real-world HTTP/3-QUIC streaming behavior.

- (2)

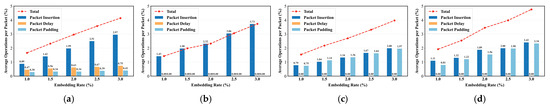

- Operational Cost Analysis: To evaluate the practical overhead introduced by the proposed covert channel, the operational cost of embedding is measured using the average operations per packet metric. As illustrated in Figure 6, the analysis reports the costs of three manipulation types (packet insertion, packet delay, and packet padding) along with the total , providing a comprehensive view of the operational footprint.

Figure 6. Operational cost analysis under different embedding rates: (a) QuicCC-SMD; (b) UDE; (c) RSE; (d) QuicCourier.

Figure 6. Operational cost analysis under different embedding rates: (a) QuicCC-SMD; (b) UDE; (c) RSE; (d) QuicCourier.

The results show that increases moderately as the embedding rate grows, which aligns with the expectation that greater embedding capacity requires more packet operations. Despite this increase, QuicCC-SMD maintains consistently low operational cost across all configurations, demonstrating that the optimized deformation matrix effectively suppresses unnecessary manipulations. For comparison, UDE relies solely on packet insertion, resulting in operational cost dominated entirely by insertion operations. RSE performs both packet padding and packet insertion, and its randomized perturbation strategy produces a similar ratio between the two types of operations. Notably, QuicCourier incurs substantially higher overhead: its design inserts many small packets to emulate legitimate traffic fluctuations, which leads to a larger number of operations to satisfy the desired embedding rate.

A deeper examination of QuicCC-SMD reveals that packet insertion is the primary component of its operational cost. It accounts for the majority of manipulations and increases steadily from 0.89% at a 1.0% embedding rate to 2.97% at 3.0%. This reflects the convex optimization design of the ADMM algorithm, which prioritizes minimally invasive operations, primarily packet insertion, while sparsity constraints suppress excessive delay or length modifications. In summary, QuicCC-SMD achieves efficient covert transmission by minimizing packet operations. This not only lowers detection risk but also reduces network overhead and system resource consumption, ensuring both stealth and practicality under diverse streaming conditions.

5.4. Undetectability Analysis

To comprehensively evaluate the undetectability of the proposed covert channel, this section analyzes statistical similarity between covert and legitimate traffic and the classifier-based detection performance against ML-based detectors.

- (1)

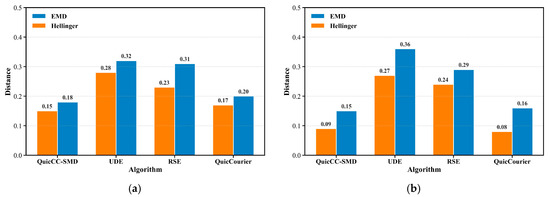

- Statistical Similarity Analysis: To quantify the statistical deviation introduced by secret data embedding, two complementary distance metrics are employed to capture global and local distributional shifts, respectively. Figure 7 presents the comparative results of these metrics under an embedding rate of 1.5%, including QuicCC-SMD and three baseline schemes (UDE, RSE, and QuicCourier).

Figure 7. Statistical similarity comparison among QuicCC-SMD, UDE, RSE, and QuicCourier under a 1.5% embedding rate: (a) Joint distribution of packet length and inter-packet delay; (b) Packet burst count distribution.

Figure 7. Statistical similarity comparison among QuicCC-SMD, UDE, RSE, and QuicCourier under a 1.5% embedding rate: (a) Joint distribution of packet length and inter-packet delay; (b) Packet burst count distribution.

Figure 7a compares the joint distribution similarity of packet length and inter-packet delay across methods. QuicCC-SMD achieves the lowest EMD value, outperforming UDE (0.32) and RSE (0.31) by approximately 77% and 72%, respectively. QuicCourier attains an EMD of 0.20, reflecting its strength in distribution alignment. These results demonstrate that the joint Markov-chain modeling in QuicCC-SMD most effectively preserves the global statistical coherence of legitimate traffic. Figure 7b presents the burst-count distribution similarity results. QuicCC-SMD again achieves the low Hellinger distance (0.09) compared with UDE (0.27) and RSE (0.24).

Overall, QuicCC-SMD achieves the lowest EMD and HD values, indicating strong preservation of statistical similarity. Notably, QuicCourier also performs well in statistical similarity due to its tailored template mechanism. These results present that QuicCC-SMD maintains covert traffic that is statistically indistinguishable from legitimate QUIC streams, a critical property for resisting feature-based detection.

- (2)

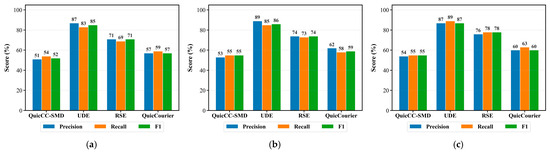

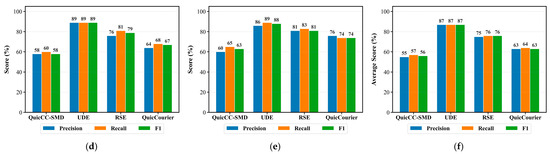

- Classifier-Based Detection Analysis: To further assess resistance against advanced traffic analysis, five representative ML-based classifiers are employed to simulate warden detection. Figure 8 compares the detection performance of QuicCC-SMD, UDE, RSE, and QuicCourier.

Figure 8. Classifier-based detection performance comparison: (a) AppScanner; (b) DF; (c) MTL; (d) TrafficFormer; (e) SmartDetector; (f) Average.

Figure 8. Classifier-based detection performance comparison: (a) AppScanner; (b) DF; (c) MTL; (d) TrafficFormer; (e) SmartDetector; (f) Average.

Across all classifiers, QuicCC-SMD consistently achieves the lowest detection accuracy, with an average F1 score of 56%, approaching the ideal indistinguishability threshold (F1 ≈ 50%). In contrast, UDE and RSE reach an average F1 score of 87% and 76%, respectively, indicating that their generated traffic remains more distinguishable. QuicCourier also performs competitively against traditional classifiers such as AppScanner, DF, and MTL but shows noticeable degradation when evaluated by advanced models like TrafficFormer and SmartDetector. This suggests that while QuicCourier effectively emulates certain statistics, its design, originally tailored for website browsing, offers limited adaptability to streaming traffic scenarios. Overall, these results demonstrate that QuicCC-SMD achieves superior resistance against both traditional and deep learning-based classifiers, outperforming the second-best scheme by approximately 7% in F1 score. This improvement stems from its ability to maintain the spatio-temporal consistency of streaming traffic features during embedding, thereby reducing classifier discriminability and enhancing covert communication robustness.

In summary, the experimental results demonstrate that QuicCC-SMD exhibits strong undetectability against both statistical and ML-based detectors, achieving high statistical indistinguishability and robust stealth performance under realistic conditions. Minor deviations are observed in the burst count distribution, where QuicCourier attains a slightly lower Hellinger distance. This minor advantage arises from QuicCourier’s MTU run-length representation, which aligns closely with burst-level traffic dynamics. However, when considering multidimensional features such as the joint distribution of packet length and inter-packet delay, QuicCC-SMD achieves a lower EMD and Hellinger distance, reflecting its superior ability to preserve coupled spatio-temporal dependencies. Overall, these findings confirm that QuicCC-SMD effectively mitigates multidimensional deviations that persist in prior schemes, achieving stronger feature consistency and superior resistance against both traditional and advanced traffic classifiers.

5.5. Reliability Analysis

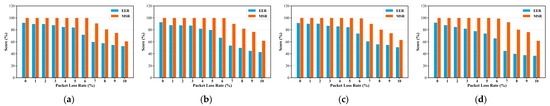

This subsection evaluates the reliability of the QuicCC-SMD prototype under real-world environment. In the experiment, a 10 KB secret file is transmitted covertly through a real-time QUIC streaming session, while controlled packet loss rates are introduced at the gateway. Multiple trials are conducted under each loss condition to ensure statistical stability. Two reliability metrics are employed: the message success rate and the effective embedding rate . The results are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Reliability evaluation under varying packet loss rates: (a) QuicCC-SMD; (b) UDE; (c) RSE; (d) QuicCourier.

The experimental results show that QuicCC-SMD maintains perfect reliability under low-loss conditions, with . As packet loss increases, retransmissions occur more frequently, increasing the total transmitted volume and thereby reducing the effective embedding rate. Despite this, the integrated retransmission mechanism sustains reliable delivery across moderate loss ranges, ensuring message integrity even when network stability fluctuates. When the packet loss rate exceeds a critical threshold, begins to decline sharply. This degradation is primarily due to interference between retransmission events and covert embedding operations, both of which depend on precise timing alignment within the carrier stream. Excessive retransmissions disrupt embedding opportunities and reduce the synchronization between packet timing and embedding actions, leading to a decrease in and occasional loss of embedded information.

For the comparison schemes, all three baselines exhibit a similar trend under worsening network conditions, as severe loss inherently reduces message arrival probability for any covert channel. However, it is notable that UDE maintains a lower than QuicCC-SMD as loss increases. This is because UDE transmits MTU-sized covert packets; losing even one such packet requires retransmitting a full MTU covert packet to preserve reliability. In contrast, QuicCourier experiences a significantly sharper decline in . Since it generates a large number of fine-grained packets with small payload sizes, high loss rates cause more frequent packet drops, triggering frequent retransmissions and amplifying reliability degradation.

Overall, these results confirm that the proposed QUIC-based covert channel achieves stable and reliable message delivery under typical Internet conditions, while gracefully degrading under severe packet loss due to the inherent constraints of retransmission-driven reliability control.

5.6. Discussion

This section discusses the overall performance and influencing factors of QuicCC-SMD. It first presents the effects of key parameters on model robustness and detection resistance, followed by a comparative performance analysis highlighting the performance and adaptability in multidimensional QUIC traffic scenarios.

- (1)

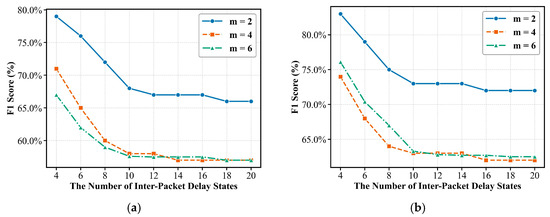

- Parameter Sensibility Analysis: Previous experimental results have shown that QuicCC-SMD, using the optimal parameters selected in Section 5.2, achieves the best resistance performance among all compared schemes in both statistical similarity and classifier-based evaluations. To further investigate how parameter variations influence this performance, a sensitivity analysis is conducted by adjusting two parameters: the number of packet length states and the number of inter-packet delay states , which jointly define the granularity of the Markov-based traffic representation. Two advanced classifiers, TrafficFormer and SmartDetector, are employed to evaluate detection resistance. The corresponding F1 score are shown in Figure 10, where and

Figure 10. Parameter sensitivity analysis using two advanced traffic classifiers: (a) TrafficFormer; (b) SmartDetector.

Figure 10. Parameter sensitivity analysis using two advanced traffic classifiers: (a) TrafficFormer; (b) SmartDetector.

As shown in Figure 10, both parameters influence the undetectability of the covert traffic. Specifically, the number of packet length states exerts a more pronounced impact: increasing enhances the representational precision of traffic state transitions, thereby improving classifier resistance. However, the performance gain saturates when , suggesting that excessive state granularity introduces redundant modeling without further benefit. Similarly, the inter-packet delay states show a consistent trend, performance improves as increases up to around . This is attributed to the limited temporal variability of real QUIC streaming traffic, where finer partitioning no longer contributes meaningful spatio-temporal distinctions. Overall, the parameters and jointly determine the representational capacity and robustness of QuicCC-SMD, and moderate values (, ) achieve the best balance between accuracy and efficiency.

- (2)

- Performance Analysis: A detailed comparative discussion is provided to position QuicCC-SMD relative to existing covert channel approaches, highlighting both shared principles and key distinctions. Similarly to QuicCourier [6], QuicCC-SMD embeds secret data through packet manipulations that leverage the highly dynamic patterns of QUIC traffic. Both schemes pursue the same objective: achieving undetectable covert transmission by modulating packet length, timing, and burst characteristics while preserving legitimate traffic patterns. They also share a design philosophy of exploiting redundancy inherent in application traffic to conceal embedded information without violating protocol semantics. A notable similarity lies in their choice of underlying transport protocol. Unlike TCP- or TLS-based covert channels, which expose header fields and require careful maintenance of connection-level protocol state [60], both QuicCC-SMD and QuicCourier operate natively on HTTP/3-QUIC. QUIC’s fully encrypted headers and connection-independent architecture allow packet manipulations to be performed without triggering protocol inconsistencies, significantly reducing implementation complexity [61]. This makes QUIC-based covert channels inherently more stable, easier to implement, and less susceptible to protocol anomaly detection.

Despite these commonalities, QuicCC-SMD differs fundamentally from QuicCourier in both design intent and traffic modeling. QuicCourier targets event-driven web browsing, where traffic is irregular and dominated by short-lived, request-response exchanges. In contrast, QuicCC-SMD is designed for multimedia streaming, which exhibits long-lived sessions, steady high throughput, MTU-sized packets, and strong temporal correlation in burst sequences [62]. By learning these persistent spatio-temporal dependencies through multi-state transition modeling, QuicCC-SMD maintains high fidelity to real streaming behavior and preserves robustness under varying network conditions.

Beyond this conceptual distinction, QuicCC-SMD also advances the embedding mechanism itself. Unlike UDE and RSE, which rely on fixed or random manipulations without modeling structural dependencies, QuicCC-SMD introduces a deformation matrix-guided optimization framework. This framework aligns embedding decisions with multidimensional dependencies in QUIC streaming flows by jointly modeling packet-length, inter-packet delay, and burst-transition states. Through Markov-based statistical learning and convex optimization, QuicCC-SMD minimizes traffic distortion while preserving legitimate spatio-temporal patterns, achieving superior stealth and efficiency.

6. Conclusions

In this work, a QUIC streaming-based covert channel framework QuicCC-SMD has been presented that dynamically embeds secret data by shaping multi-dimensional traffic features to preserve the spatio-temporal characteristics of legitimate QUIC flows. By constructing Markov chain-based state representations, formulating a convex optimization problem to derive a cost-efficient deformation matrix, and performing packet manipulations under a periodic online strategy, QuicCC-SMD enables fine-grained adaptation to the evolving dynamics of HTTP/3-QUIC streaming traffic. Comprehensive experiments on real-world QUIC streaming traffic demonstrate that QuicCC-SMD achieves high covert transmission efficiency, strong undetectability, and robust reliability. In statistical similarity evaluation, it attains the lowest EMD and Hellinger distance among all schemes. In classifier-based evaluation, QuicCC-SMD achieves an average F1 score of 56%, outperforming the second-best method by approximately 7%, and significantly lowering detection accuracy under advanced deep learning-based classifiers. These results confirm that QuicCC-SMD effectively maintains multidimensional feature consistency, a key advantage over fixed-pattern or random-perturbation baselines (UDE, RSE) and template-driven methods such as QuicCourier.

Meanwhile, several limitations should also be acknowledged. The Markov-based modeling introduces additional computational cost when the state space increases, and the convex optimization requires periodic recomputation to track long-term traffic pattern drift. Looking forward, two promising directions merit exploration. First, extending QuicCC-SMD to multi-flow collaborative embedding may leverage correlations across concurrent QUIC streams to improve throughput and stealth. Second, integrating reinforcement learning-based adaptive optimization could enable real-time parameter adjustment under varying network conditions, enhancing both robustness and efficiency. Together, these extensions will further advance the practicality and adaptability of QUIC-based covert communication.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.Z. and D.L.; methodology, D.Z. and D.L.; software, D.Z., D.L. and J.H.; validation, J.H., L.G. and X.Y.; formal analysis, L.G. and X.Y.; data curation, L.G. and X.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, D.Z.; writing—review and editing, D.Z., D.L., J.H., L.G. and X.Y.; visualization, J.H.; supervision, J.H.; project administration, J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to the dataset containing real HTTP/3-QUIC streaming traffic that may include identifiable service metadata.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Xie, J. Information leakage detection and risk assessment of intelligent mobile devices. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadse, A.; Dakhane, D. A review on network covert channel construction and attack detection. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2025, 37, e8316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Gao, F.; Chen, Z.; Li, Z. Achieving anonymous and covert reporting on public blockchain networks. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husák, M.; Čermák, M.; Jirsík, T.; Čeleda, P. HTTPS traffic analysis and client identification using passive ssl/tls fingerprinting. EURASIP J. Inf. Secur. 2016, 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Goldberg, I. Improved website fingerprinting on tor. In Proceedings of the 12th ACM Workshop on Privacy in the Electronic Society, Berlin, Germany, 4 November 2013; pp. 201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Liu, W.; Liu, G.; Gao, B.; Nie, F. QuicCourier: Leveraging the dynamics of quic-based website browsing behaviors through proxy for covert communication. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2025, 22, 4516–4533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caviglione, L. Trends and challenges in network covert channels countermeasures. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Huang, L.; Lu, X.; Yang, W. A novel comprehensive steganalysis of transmission control protocol/internet protocol covert channels based on protocol behaviors and support vector machine. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2015, 8, 1279–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolov, A.; Kogos, K. Inter-packet delays normalization to limit ip covert timing channels. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 169, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Song, T.; Yang, Y. Generic and sensitive anomaly detection of network covert timing channels. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2022, 20, 4085–4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iv, H.; Georgiou, M.; Malozemoff, A.; Shrimpton, T. Security foundations for application-based covert communication channels. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, San Francisco, CA, USA, 22–26 May 2022; pp. 1971–1986. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson, R.; Houmansadr, A.; Shmatikov, V. CovertCast: Using live streaming to evade internet censorship. Proc. Priv. Enhancing Technol. 2016, 2016, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barradas, D.; Santos, N.; Rodrigues, L. Deltashaper: Enabling unobservable censorship-resistant tcp tunneling over videoconferencing streams. Proc. Priv. Enhancing Technol. 2017, 4, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barradas, D. Unobservable Multimedia-Based Covert Channels for Internet Censorship Circumvention. Ph.D. Dissertation, Instituto Superior Técnico, Lisbon, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mirnajafizadeh, M.; Sethuram, R.; Mohaisen, D.; Nyang, D.; Jang, R. Enhancing network attack detection with distributed and in-network data collection system. In Proceedings of the 33rd USENIX Security Symposium, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 14–16 August 2024; pp. 5161–5178. [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni, G. Security and service vulnerabilities with http/3. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Communication Systems & Networks, Bangalore, India, 3–7 January 2024; pp. 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Rao, C.; Huang, J.; Guan, L.; Tian, M.; Liu, W. A dynamic website fingerprinting defense by emulating spatio-temporal traffic features. Electronics 2025, 14, 4441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wails, R.; Stange, A.; Troper, E.; Caliskan, A.; Dingledine, R.; Jansen, R.; Sherr, M. Learning to behave: Improving covert channel security with behavior-based designs. Proc. Priv. Enhancing Technol. 2022, 3, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bistarelli, S.; Ceccarelli, M.; Luchini, C.; Mercanti, I.; Santini, F. A preliminary study on the creation of a covert channel with http headers. In Proceedings of the 8th Italian Conference on Cyber Security, Salerno, Italy, 8–12 April 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Semushin, S.; Seytnazarov, S. HTTP header reordering-based covert channel protocol. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Signal Processing and Information Security, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 8–9 November 2023; pp. 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Kwecka, Z. Application Layer Covert Channel Analysis and Detection. Bachelor’s Dissertation, Napier University, Edinburgh, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Xue, Y.; Hu, J. A stealthy covert storage channel for asymmetric surveillance volte endpoints. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 102, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, L.; Neyron, P.; Richard, O. On robust covert channels inside dns. In Proceedings of the IFIP International Information Security Conference, Pafos, Cyprus, 21–23 May 2009; pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, X.; Li, Q.; Sun, S.; Niu, X. The research on information hiding based on command sequence of ftp protocol. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge-Based and Intelligent Information and Engineering Systems, Melbourne, Australia, 14–16 September 2005; pp. 1079–1085. [Google Scholar]

- Bistarelli, S.; Imparato, A.; Santini, F. A tcp-based covert channel with integrity check and retransmission. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2024, 23, 3481–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giffin, J.; Greenstadt, R.; Litwack, P.; Tibbetts, R. Covert messaging through tcp timestamps. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Privacy Enhancing Technologies, San Francisco, CA, USA, 14–15 April 2002; pp. 194–208. [Google Scholar]

- Zander, S.; Armitage, G.; Branch, P. Covert channels in the ip time to live field. In Proceedings of the Australian Telecommunication Networks and Applications Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 29 November–1 December 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mavani, M.; Ragha, L. Covert channel in ipv6 destination option extension header. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Circuits, Systems, Communication and Information Technology Applications, Mumbai, India, 4–5 April 2014; pp. 219–224. [Google Scholar]

- Cabaj, K.; Gregorczyk, M.; Mazurczyk, W. Software-defined networking-based crypto ransomware detection using http traffic characteristics. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2018, 66, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabuk, S.; Brodley, C.; Shields, C. IP covert timing channels: Design and detection. In Proceedings of the 11th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Washington, DC, USA, 25–29 October 2004; pp. 178–187. [Google Scholar]

- Cabuk, S. Network Covert Channels: Design, Analysis, Detection, and Elimination. Ph.D. Dissertation, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chong, F.; Zhao, B. A Covert Channel Analysis of a Real Switch; Technical Report; University of California: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tahir, R.; Khan, M.; Gong, X.; Ahmed, A.; Ghassami, A.; Kazmi, H.; Caesar, M.; Zaffar, F.; Kiyavash, N. Sneak-peek: High speed covert channels in data center networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Communications, San Francisco, CA, USA, 10–15 April 2016; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mazurczyk, W.; Smolarczyk, M.; Szczypiorski, K. Retransmission steganography and its detection. Soft Comput. 2011, 15, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Baker, T.; Li, Y.; Nawaz, R.; Tan, Y. Building covert timing channel of the iot-enabled mts based on multi-stage verification. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 24, 2578–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Sun, X.; Huang, J.; Shi, N.; Liang, C. Privacy-preserving covert channels in volte via inter-frame delay modulation. In International Conference on Artificial Intelligence Security and Privacy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 74–88. [Google Scholar]

- Stillman, R. Detecting ip covert timing channels by correlating packet timing with memory content. In Proceedings of the IEEE SoutheastCon 2008 Conference, Huntsville, AL, USA, 3–6 April 2008; pp. 204–209. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Schliep, M.; Hopper, N. Facet: Streaming over videoconferencing for censorship circumvention. In Proceedings of the 13th Workshop on Privacy in the Electronic Society, Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 3 November 2014; pp. 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, J.; Tan, Z.; Huang, Y.; Hu, N. Stealth: A heterogeneous covert access channel for mix-net. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Data Science in Cyberspace, Guilin, China, 11–13 July 2022; pp. 118–125. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, C.; Li, Z.; Luo, X. A covert communication method based on time attributes shifting of online video bullet comment. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 70, 6472–6483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.; Ensafi, R. The use of push notification in censorship circumvention. Proc. Free Open Commun. Internet 2023, 2, 22–32. [Google Scholar]