Graph-Attention-Regularized Deep Support Vector Data Description for Semi-Supervised Anomaly Detection: A Case Study in Automotive Quality Control

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Data and Basic Notation

2.2. Latent One-Class Score

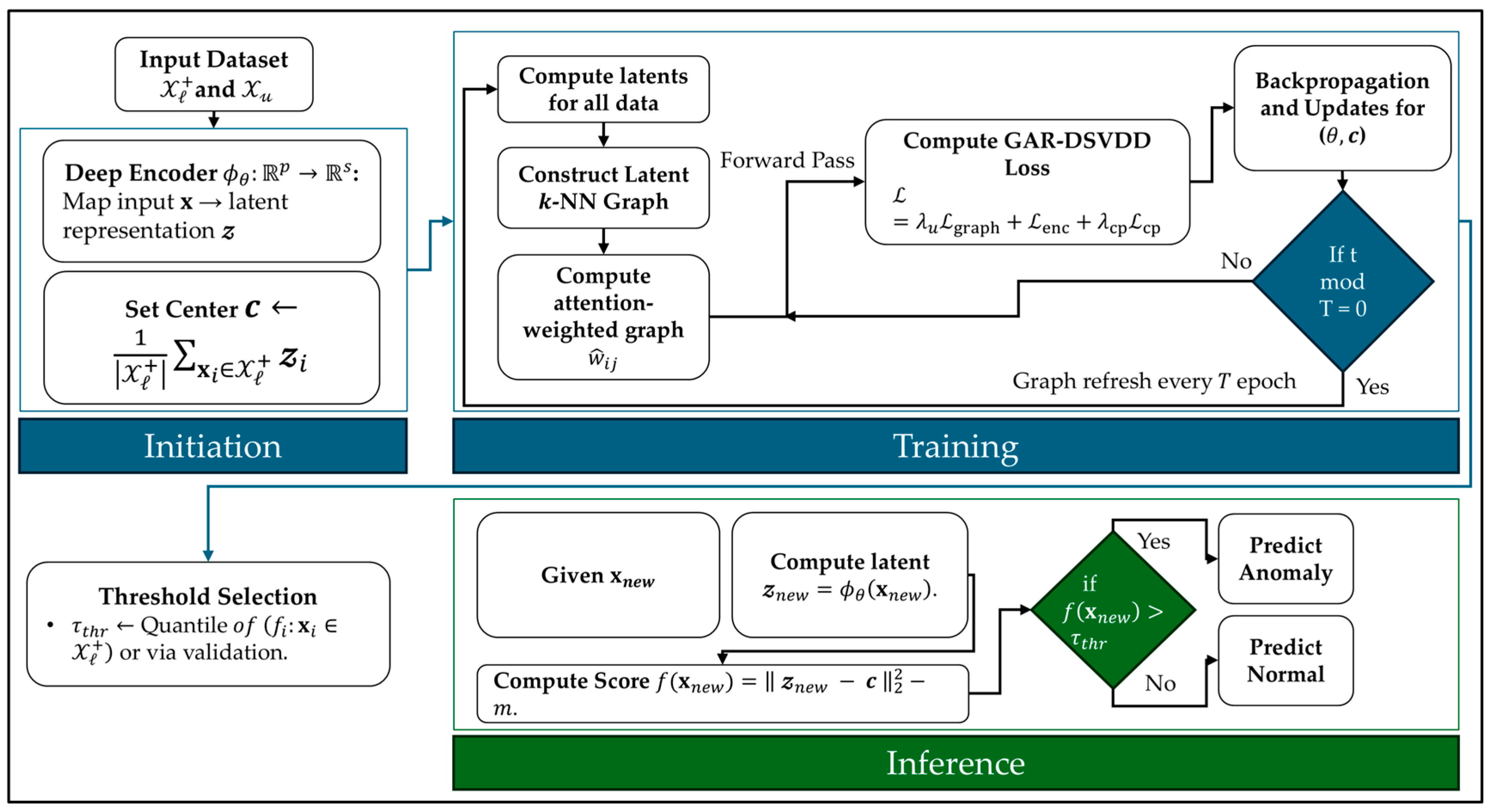

3. Graph-Attention-Regularized Deep SVDD

3.1. Latent Attention-Weighted -NN Graph

3.2. GAR-DSVDD Loss Components

3.2.1. Unlabeled Geometry via Neighbor Smoothness on Squared Distances

3.2.2. Labeled-Normal Enclosure

3.2.3. Unlabeled Center Pull

3.3. GAR-DSVDD Overall Objective Function

| Algorithm 1: GAR-DSVDD (training) |

| Inputs: , ; ; graph params ; weights ; refresh period ; total epochs . ( is the attention softmax temperature) |

Outputs: decision threshold ( is the decision threshold)

|

| Inference (testing) Given :

|

3.4. GAR-DSVDD Hyperparameter Tuning and Selection

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

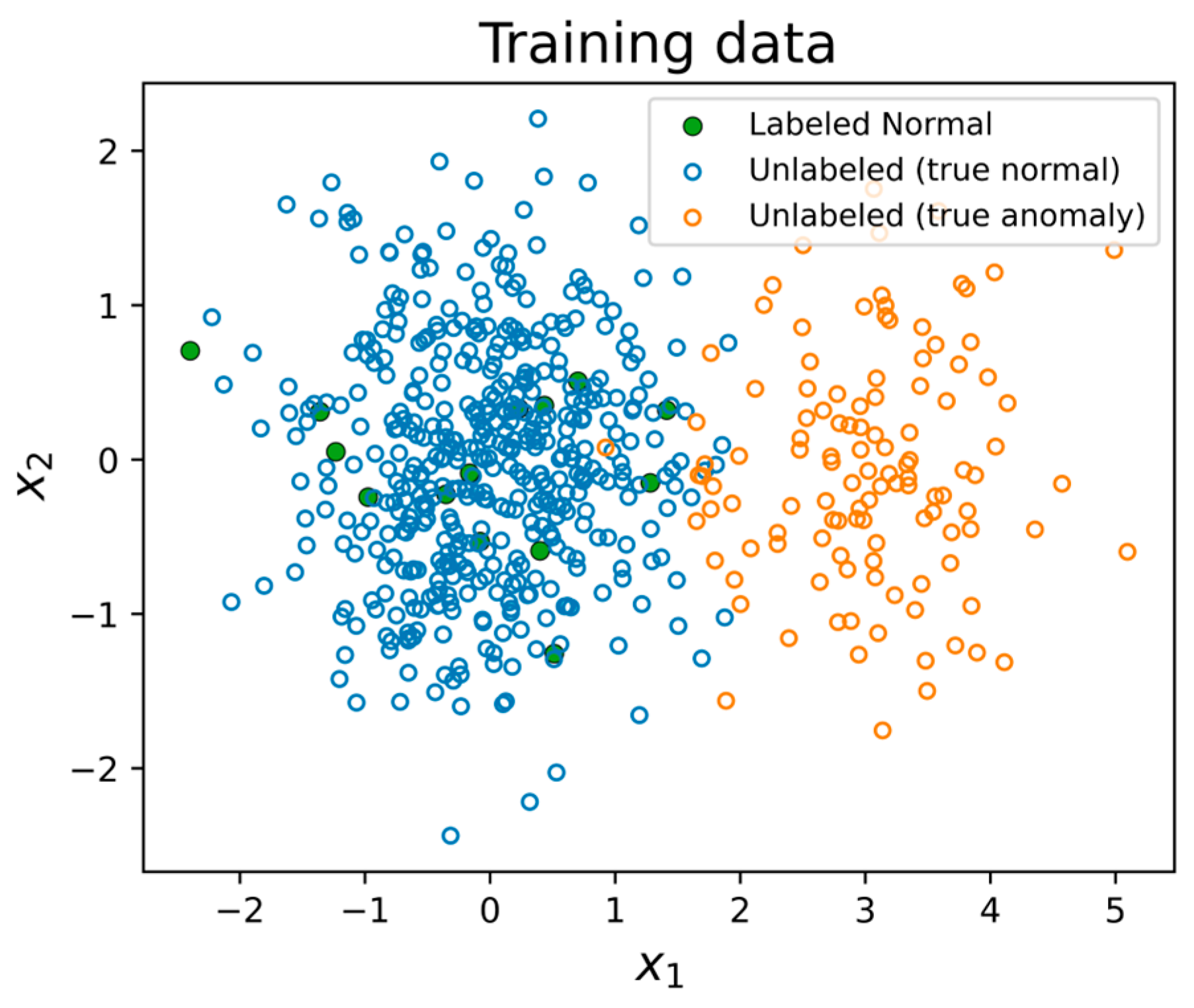

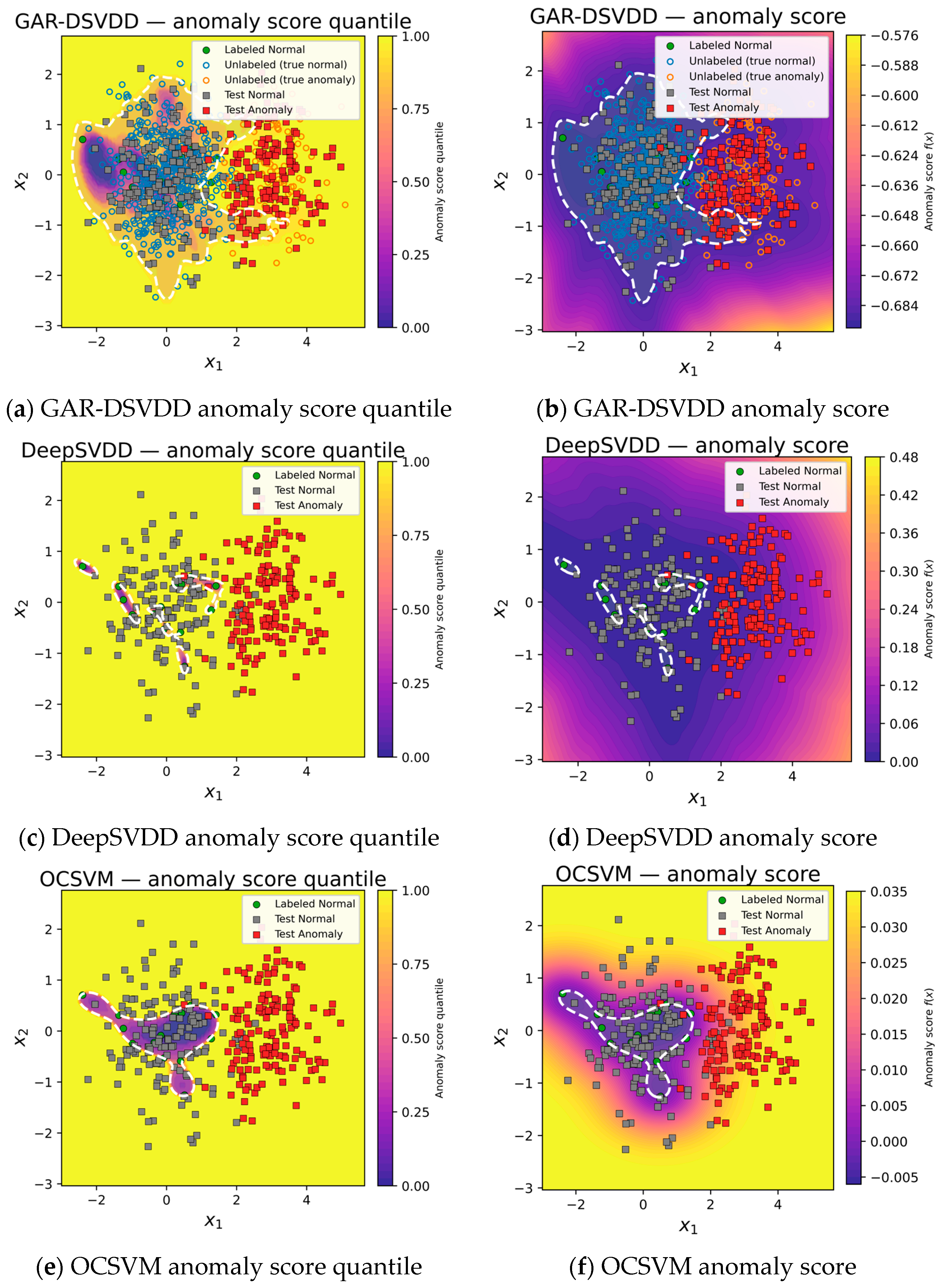

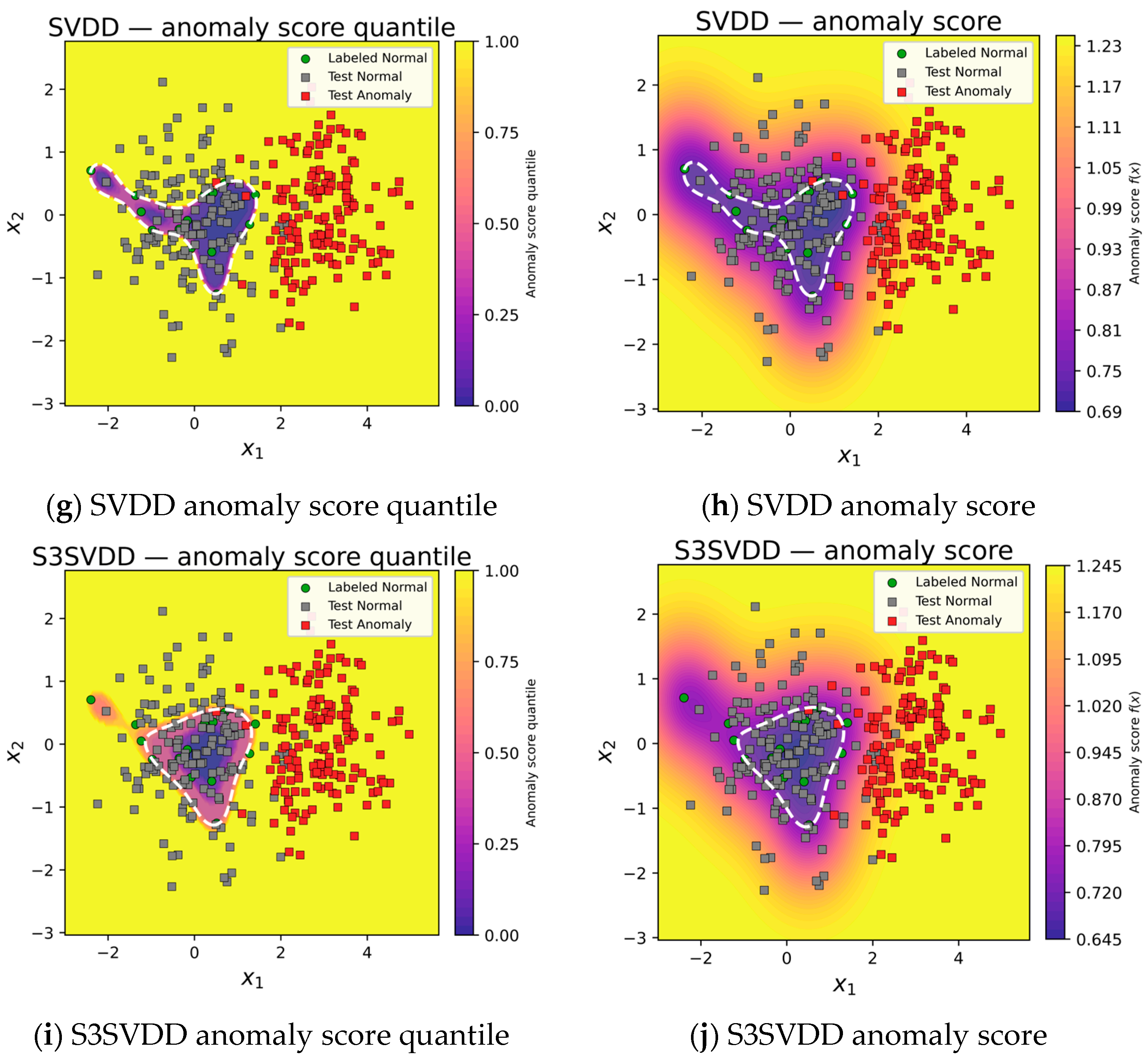

4.2. Simulated Data

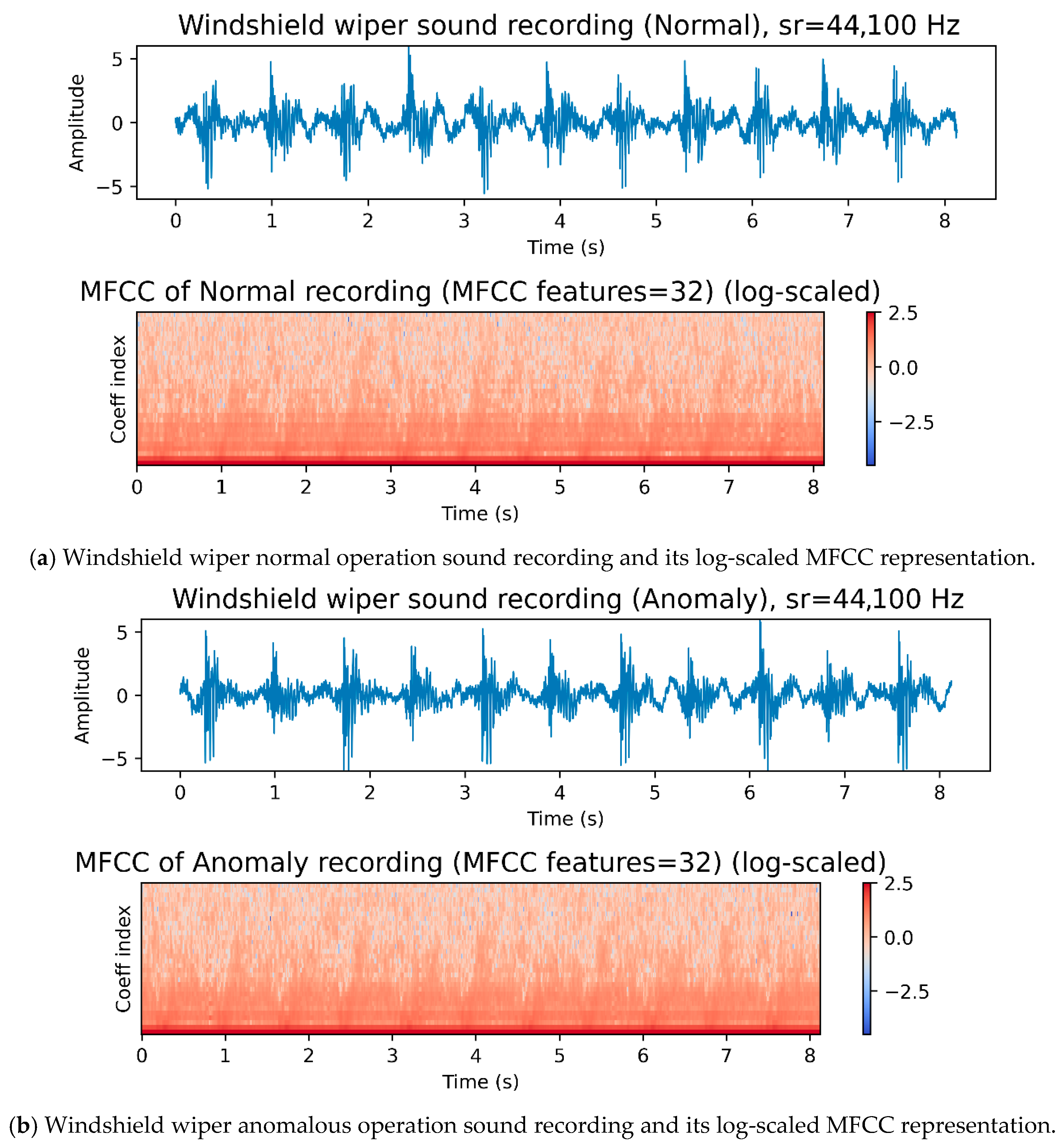

4.3. Case Study: Windshield Wiper Acoustics

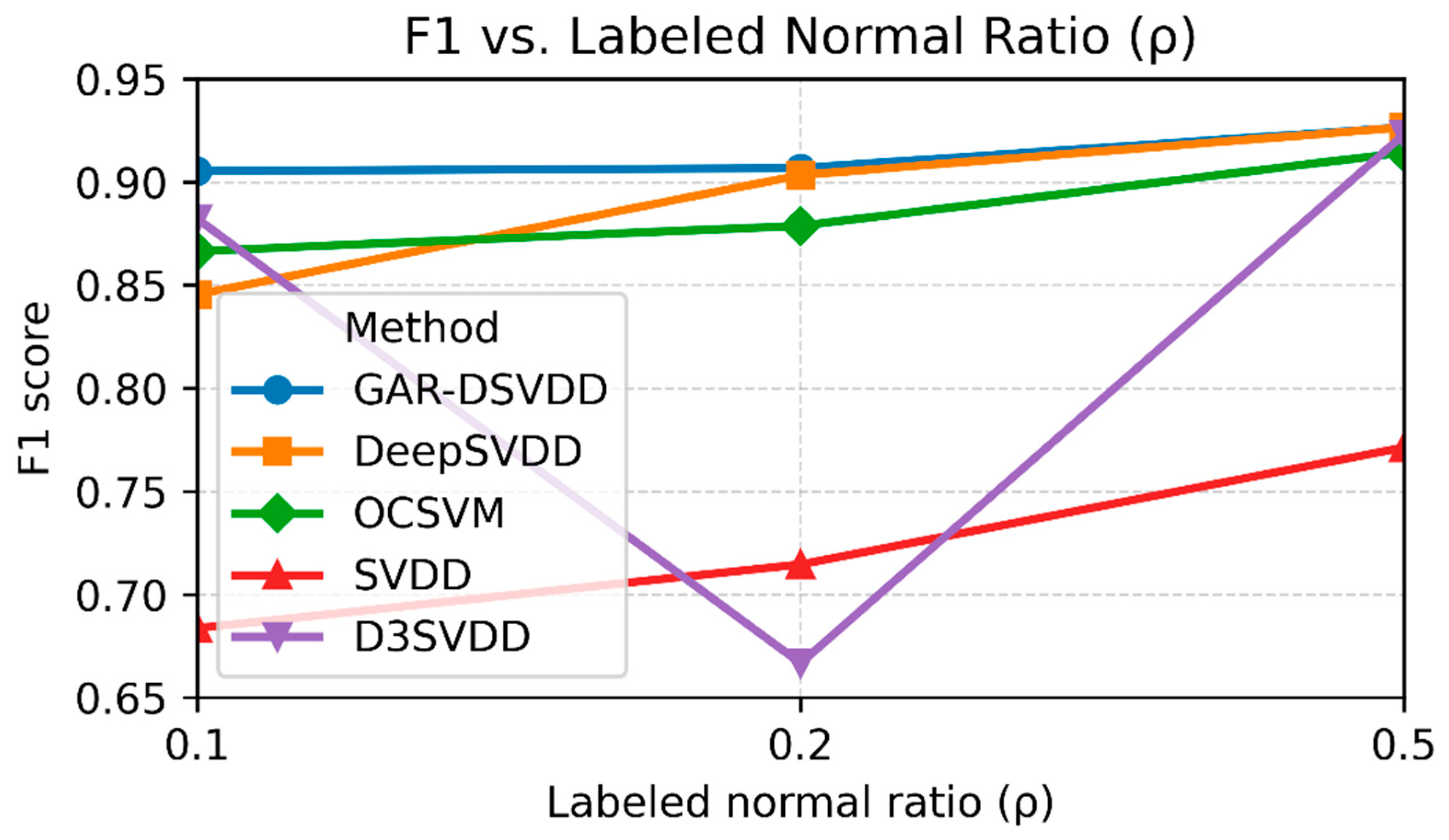

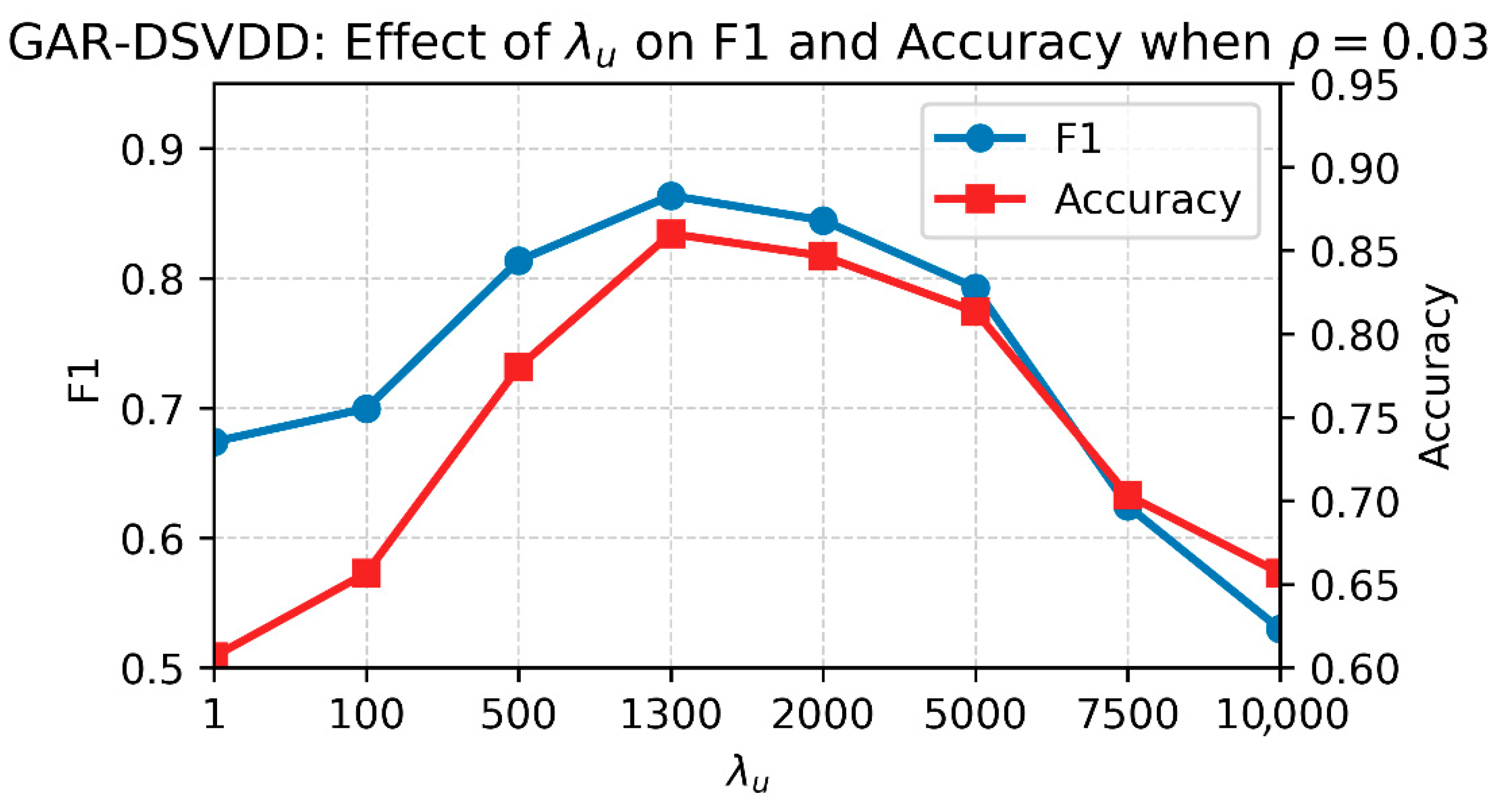

4.4. Sensitivity Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AdamW | Adaptive Moment Estimation with (decoupled) Weight decay |

| DeepSVDD | Deep Support Vector Data Description |

| GAR-DSVDD | Graph-Attention-Regularized Deep Support Vector Data Description |

| -NN | k-Nearest Neighbors |

| MFCC | Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients |

| OCSVM | One-Class Support Vector Machine |

| ReLU | Rectified Linear Unit |

| S3SVDD | Graph-based Semi-Supervised Support Vector Data Description |

| SVDD | Support Vector Data Description |

Appendix A. Gradients of the GAR-DSVDD Objective

References

- Cai, L.; Yin, H.; Lin, J.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, D. A relevant variable selection and SVDD-based fault detection method for process monitoring. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2022, 20, 2855–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Boulanger, P. A survey of heart anomaly detection using ambulatory Electrocardiogram (ECG). Sensors 2020, 20, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakong, W.; Kim, W. An adaptive policy-based anomaly object control system for enhanced cybersecurity. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 55281–55291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhindi, T.J.; Alturkistani, O.; Baek, J.; Jeong, M.K. Multi-class support vector data description with dynamic time warping kernel for monitoring fires in diverse non-fire environments. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 21958–21970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhindi, T.J.; Baek, J.; Jeong, Y.-S.; Jeong, M.K. Orthogonal binary singular value decomposition method for automated windshield wiper fault detection. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 3383–3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tax, D.M.; Duin, R.P. Support vector data description. Mach. Learn. 2004, 54, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schölkopf, B.; Platt, J.C.; Shawe-Taylor, J.; Smola, A.J.; Williamson, R.C. Estimating the support of a high-dimensional distribution. Neural Comput. 2001, 13, 1443–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Ghahramani, Z.; Lafferty, J.D. Semi-supervised learning using gaussian fields and harmonic functions. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML-03), Washington, DC, USA, 21–24 August 2003; pp. 912–919. [Google Scholar]

- Belkin, M.; Niyogi, P.; Sindhwani, V. Manifold regularization: A geometric framework for learning from labeled and unlabeled examples. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2006, 7, 2399–2494. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Wu, J.; Yang, J.; Xue, S.; Peng, H.; Zhou, C.; Chen, H.; Li, Z.; Sheng, Q.Z. Deep graph level anomaly detection with contrastive learning. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wu, J.; Xue, S.; Yang, J.; Zhou, C.; Sheng, Q.Z.; Xiong, H.; Akoglu, L. A comprehensive survey on graph anomaly detection with deep learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2021, 35, 12012–12038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, H.; Tong, H.; An, B.; King, I.; Aggarwal, C.; Pang, G. Deep graph anomaly detection: A survey and new perspectives. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2025, 37, 5106–5126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, P.; Nguyen, V.; Dinh, M.; Le, T.; Tran, D.; Ma, W. Graph-based semi-supervised support vector data description for novelty detection. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Killarney, Ireland, 12–17 July 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liu, S.; Bai, Y. The manifold regularized SVDD for noisy label detection. Inf. Sci. 2023, 619, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Liu, C.; Desmet, W.; Gryllias, K. Semi-supervised CNN-based SVDD anomaly detection for condition monitoring of wind turbines. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, Boston, MA, USA, 7–8 December 2022; p. V001T001A019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Luxburg, U. A tutorial on spectral clustering. Stat. Comput. 2007, 17, 395–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelnik-Manor, L.; Perona, P. Self-tuning spectral clustering. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2004, 17, 1601–1608. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C. A survey of large-scale graph-based semi-supervised classification algorithms. Int. J. Cogn. Comput. Eng. 2022, 3, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruff, L.; Vandermeulen, R.; Goernitz, N.; Deecke, L.; Siddiqui, S.A.; Binder, A.; Müller, E.; Kloft, M. Deep one-class classification. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 4393–4402. [Google Scholar]

- Pota, M.; De Pietro, G.; Esposito, M. Real-time anomaly detection on time series of industrial furnaces: A comparison of autoencoder architectures. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 124, 106597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neloy, A.A.; Turgeon, M. A comprehensive study of auto-encoders for anomaly detection: Efficiency and trade-offs. Mach. Learn. Appl. 2024, 17, 100572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tack, J.; Mo, S.; Jeong, J.; Shin, J. Csi: Novelty detection via contrastive learning on distributionally shifted instances. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 11839–11852. [Google Scholar]

- Hojjati, H.; Ho, T.K.K.; Armanfard, N. Self-supervised anomaly detection in computer vision and beyond: A survey and outlook. Neural Netw. 2024, 172, 106106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalapathy, R.; Chawla, S. Deep learning for anomaly detection: A survey. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.03407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, G.; Shen, C.; Cao, L.; Hengel, A.V.D. Deep learning for anomaly detection: A review. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruff, L.; Kauffmann, J.R.; Vandermeulen, R.A.; Montavon, G.; Samek, W.; Kloft, M.; Dietterich, T.G.; Müller, K.-R. A unifying review of deep and shallow anomaly detection. Proc. IEEE 2021, 109, 756–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Van Leeuwen, M. A survey on explainable anomaly detection. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 2023, 18, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, R.; Heskes, T. Autoencoders for Anomaly Detection are Unreliable. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.13864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, S.Y.; Bu, F.; Kang, S.; Kim, K.; Yoo, J.; Shin, K. Rethinking reconstruction-based graph-level anomaly detection: Limitations and a simple remedy. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 95931–95962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velickovic, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Lio, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph attention networks. Stat 2017, 1050, 10–48550. [Google Scholar]

- Salleh, I.; Zain, M.M.; Bakar, A.A. Modeling and simulation of acting force on a flexible automotive wiper. Appl. Model. Simul. 2018, 2, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Reddyhoff, T.; Dobre, O.; Le Rouzic, J.; Gotzen, N.-A.; Parton, H.; Dini, D. Friction induced vibration in windscreen wiper contacts. J. Vib. Acoust. 2015, 137, 041009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, A.; Garg, N.K. Environmental Sound Classification: A descriptive review of the literature. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2022, 16, 200115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madanian, S.; Chen, T.; Adeleye, O.; Templeton, J.M.; Poellabauer, C.; Parry, D.; Schneider, S.L. Speech emotion recognition using machine learning—A systematic review. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2023, 20, 200266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannem, K.R.; Mengiste, E.; Hasan, S.; de Soto, B.G.; Sacks, R. Smart audio signal classification for tracking of construction tasks. Autom. Constr. 2024, 165, 105485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Accuracy | F1 | Detection Rate | Precision | Specificity | Balanced Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAR-DSVDD | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.99 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.92 |

| DeepSVDD | 0.56 | 0.69 | 1.00 | 0.53 | 0.11 | 0.56 |

| OCSVM | 0.76 | 0.81 | 0.99 | 0.68 | 0.53 | 0.76 |

| SVDD | 0.71 | 0.77 | 0.99 | 0.63 | 0.43 | 0.71 |

| S3SVDD | 0.69 | 0.76 | 0.99 | 0.62 | 0.38 | 0.69 |

| Experiment (Over Different Seeds) | GAR-DSVDD | DeepSVDD | OCSVM | SVDD | S3SVDD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.86 | 0.68 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.74 |

| 2 | 0.83 | 0.70 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.78 |

| 3 | 0.80 | 0.73 | 0.80 | 0.70 | 0.70 |

| 4 | 0.92 | 0.69 | 0.81 | 0.77 | 0.76 |

| 5 | 0.88 | 0.69 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.67 |

| 6 | 0.80 | 0.72 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.79 |

| 7 | 0.81 | 0.69 | 0.76 | 0.68 | 0.69 |

| 8 | 0.86 | 0.68 | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.74 |

| 9 | 0.78 | 0.69 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.76 |

| 10 | 0.85 | 0.68 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.77 |

| Mean | 0.84 | 0.70 | 0.78 | 0.74 | 0.74 |

| Standard deviation | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| p-value (Wilcoxon) | - | ||||

| p-value (paired t-test) | - |

| Feature Family | Recording Dimension (Means and Standard Deviations) * | Brief Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| MFCC (32) | 64 | Cepstral summary of spectral envelope on the mel scale, a widely adopted baseline in recent ESC/SER studies. | [33,34] |

| ΔMFCC (32) | 64 | First-order derivative of MFCCs capturing short-term spectral dynamics. | [34] |

| Δ2MFCC (32) | 64 | Second-order derivative (acceleration) of MFCCs, emphasizing rapid spectral change. | [34] |

| Chroma (12) | 24 | Energy folded into 12 pitch-class bins; it reflects tonal/resonant structure seen in mechanical acoustics. | [33,34] |

| Spectral centroid | 2 | Power-weighted mean frequency (proxy for “brightness”). | [33,34] |

| Spectral bandwidth | 2 | Spread around the centroid (spectral dispersion). | [33] |

| Spectral roll-off (95%) | 2 | Frequency below which 95% of energy lies (high-frequency content indicator). | [33,34] |

| RMS energy | 2 | Framewise signal power (overall loudness proxy). | [33,34] |

| ZCR | 2 | Sign-change rate (simple proxy for roughness/high-frequency content). | [33,34] |

| Method | Accuracy | F1 | Detection Rate | Precision | Specificity | Balanced Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAR-DSVDD | 0.92 | 0.91 | 1 | 0.83 | 0.86 | 0.93 |

| DeepSVDD | 0.42 | 0.59 | 1 | 0.42 | 0 | 0.5 |

| OCSVM | 0.42 | 0.59 | 1 | 0.42 | 0 | 0.5 |

| SVDD | 0.42 | 0.59 | 1 | 0.42 | 0 | 0.5 |

| S3SVDD | 0.42 | 0.59 | 1 | 0.42 | 0 | 0.5 |

| Experiment (Over Different Seeds) | GAR-DSVDD | DeepSVDD | OCSVM | SVDD | S3SVDD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.86 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| 2 | 0.93 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.82 | 0.8 |

| 3 | 0.76 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.52 | 0.5 |

| 4 | 0.79 | 0.60 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.63 |

| 5 | 0.67 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.63 |

| 6 | 0.91 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.59 |

| 7 | 0.83 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.45 |

| 8 | 0.97 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.74 |

| 9 | 0.96 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| 10 | 0.90 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.69 | 0.63 |

| Mean | 0.86 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 0.62 |

| Standard deviation | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| p-value (Wilcoxon) | - | ||||

| p-value (paired t-test) | - |

| GAR-DSVDD | DeepSVDD | OCSVM | SVDD | S3SVDD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.68 | 0.88 |

| 0.2 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.71 | 0.77 |

| 0.5 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.77 | 0.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alhindi, T.J. Graph-Attention-Regularized Deep Support Vector Data Description for Semi-Supervised Anomaly Detection: A Case Study in Automotive Quality Control. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3876. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233876

Alhindi TJ. Graph-Attention-Regularized Deep Support Vector Data Description for Semi-Supervised Anomaly Detection: A Case Study in Automotive Quality Control. Mathematics. 2025; 13(23):3876. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233876

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlhindi, Taha J. 2025. "Graph-Attention-Regularized Deep Support Vector Data Description for Semi-Supervised Anomaly Detection: A Case Study in Automotive Quality Control" Mathematics 13, no. 23: 3876. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233876

APA StyleAlhindi, T. J. (2025). Graph-Attention-Regularized Deep Support Vector Data Description for Semi-Supervised Anomaly Detection: A Case Study in Automotive Quality Control. Mathematics, 13(23), 3876. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233876