KAN-Former: 4D Trajectory Prediction for UAVs Based on Cross-Dimensional Attention and KAN Decomposition

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

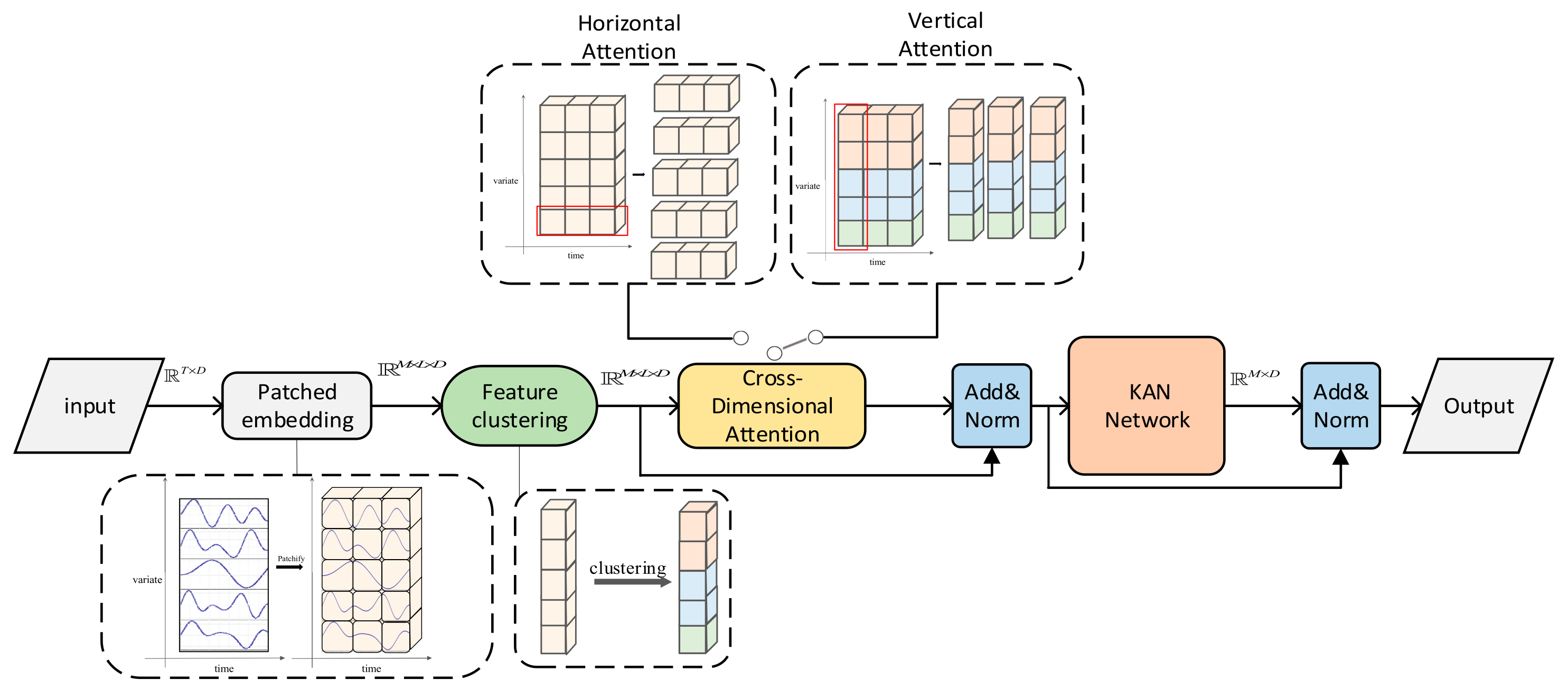

- Methodological innovation: A cross-dimensional attention mechanism is proposed. Vertical attention explicitly models physical correlations among multivariate variables (e.g., attitude–wind speed coupling) based on hierarchical clustering priors. Horizontal attention, on the other hand, employs a blockwise dimensionality reduction strategy to capture long-term temporal dependencies efficiently.

- (2)

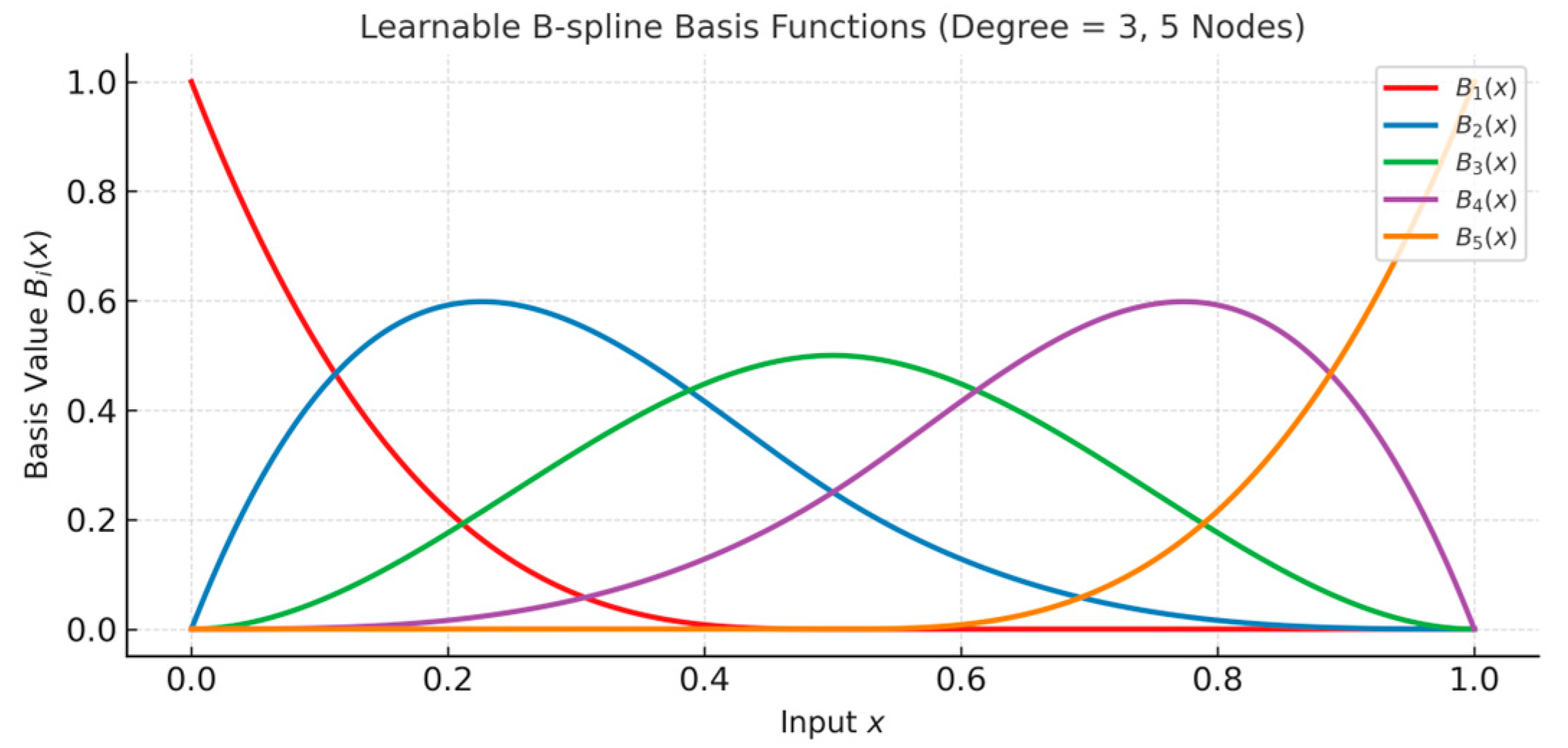

- Theoretical innovation: The Kolmogorov–Arnold decomposition theorem is introduced in trajectory prediction, replacing FFN with learnable B-spline basis function combinations to approximate high-dimensional nonlinear mappings through low-dimensional functions, avoiding the curse of dimensionality.

- (3)

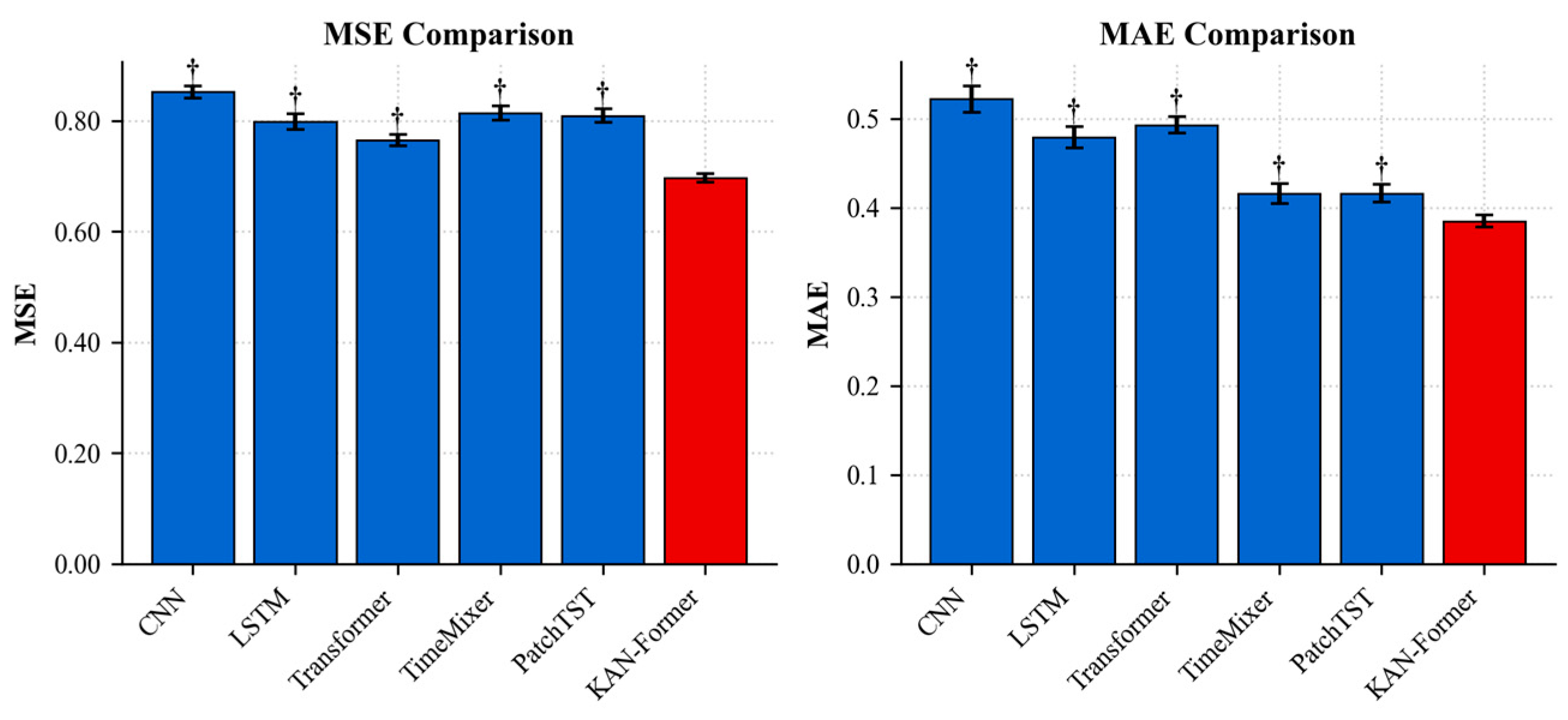

- Performance improvement on 21-dimensional multimodal data. MSE is reduced by 8.96% compared to Transformer and MAE is reduced by 7.43% compared to TimeMixer. Feature clustering results enhance model interpretability, providing a physical basis for engineering deployment and informed decision-making.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Related Work

2.1.1. State Estimation-Based Methods

2.1.2. Dynamics Model-Based Methods

2.1.3. Neural Network-Based Methods

2.2. KAN-Former

2.2.1. Patched Embedding

2.2.2. Cross-Dimensional Attention Mechanism

| Algorithm 1. Cross-Dimensional Attention Configuration Strategies |

| Input: X: input tensor of shape [Batch, Patches, Time, Features] config: one of {time_first, channel_first, alternate} L: total number of layers |

| Begin: # Strategy 1: Time-First if config == ‘time_first’ then for l = 1 to L do X ← Horizontal_Attention(X) # Capture temporal dependencies X ← Vertical_Attention(X) # Model feature correlations end for # Strategy 2: Channel-First else if config == ‘channel_first’ then for l = 1 to L do X ← Vertical_Attention(X) # Model feature correlations X ← Horizontal_Attention(X) # Capture temporal dependencies end for # Strategy 3: Alternate else if config == ‘alternate’ then for l = 1 to L do if l % 2 == 1 then X ← Horizontal_Attention(X) # Odd layers: temporal first else X ← Vertical_Attention(X) # Even layers: feature first end if end for end if Y ← X Return Y End |

- (1)

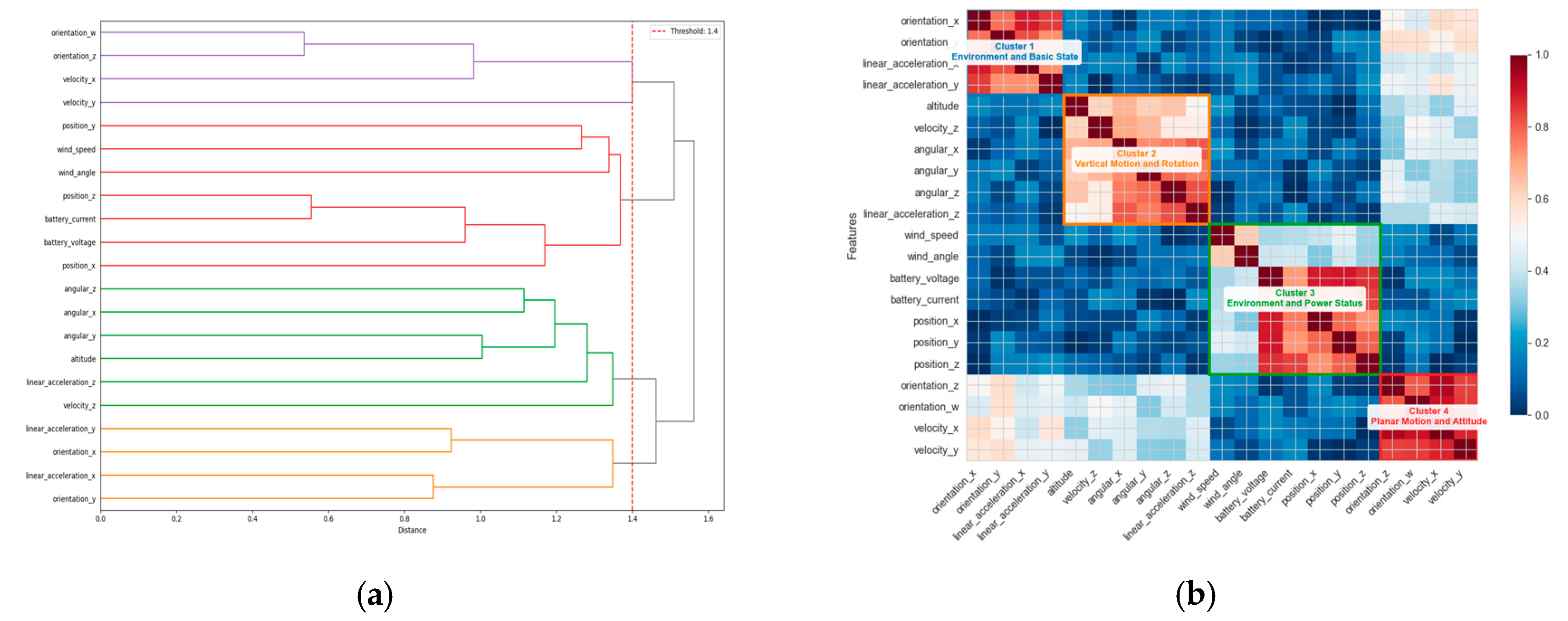

- Vertical Attention (Feature-Dimension Modeling)

| Algorithm 2. Hierarchical Feature Clustering Based on Pearson Correlation Coefficient |

| Input: UAV feature matrix , stopping threshold τ_threshold Output: Cluster label vector , linkage matrix |

| Begin // Initialization 1. D ← number of columns in F // D = 21 (total UAV features) 2. clusters ← {{1}, {2}, …, {D}} // Each feature as an initial cluster 3. Z ← empty matrix // Stores cluster merging records // Compute correlation and distance matrices 4. For all feature pairs (i,j) where 1 ≤i < j≤ D: a. // Temporal mean of feature i b. // Temporal mean of feature j c. 5. Construct distance matrix where // Iterative cluster merging (average linkage) 6. While minimum inter-cluster distance ≤ τ_threshold: a. // Determined by avg_dist b. // Merge clusters c. clusters ← // Update cluster set d. e. Z ← Z with . appended as a new row // Generate cluster labels 7. For each feature j (1≤j≤D): ← cluster ID containing feature j 8. Return l and Z End |

- (2)

- Horizontal Attention (Temporal Dimension Modeling)

2.2.3. Nonlinear Mapping Module Based on KAN Network

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Setup

3.2. Prediction Results

3.3. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

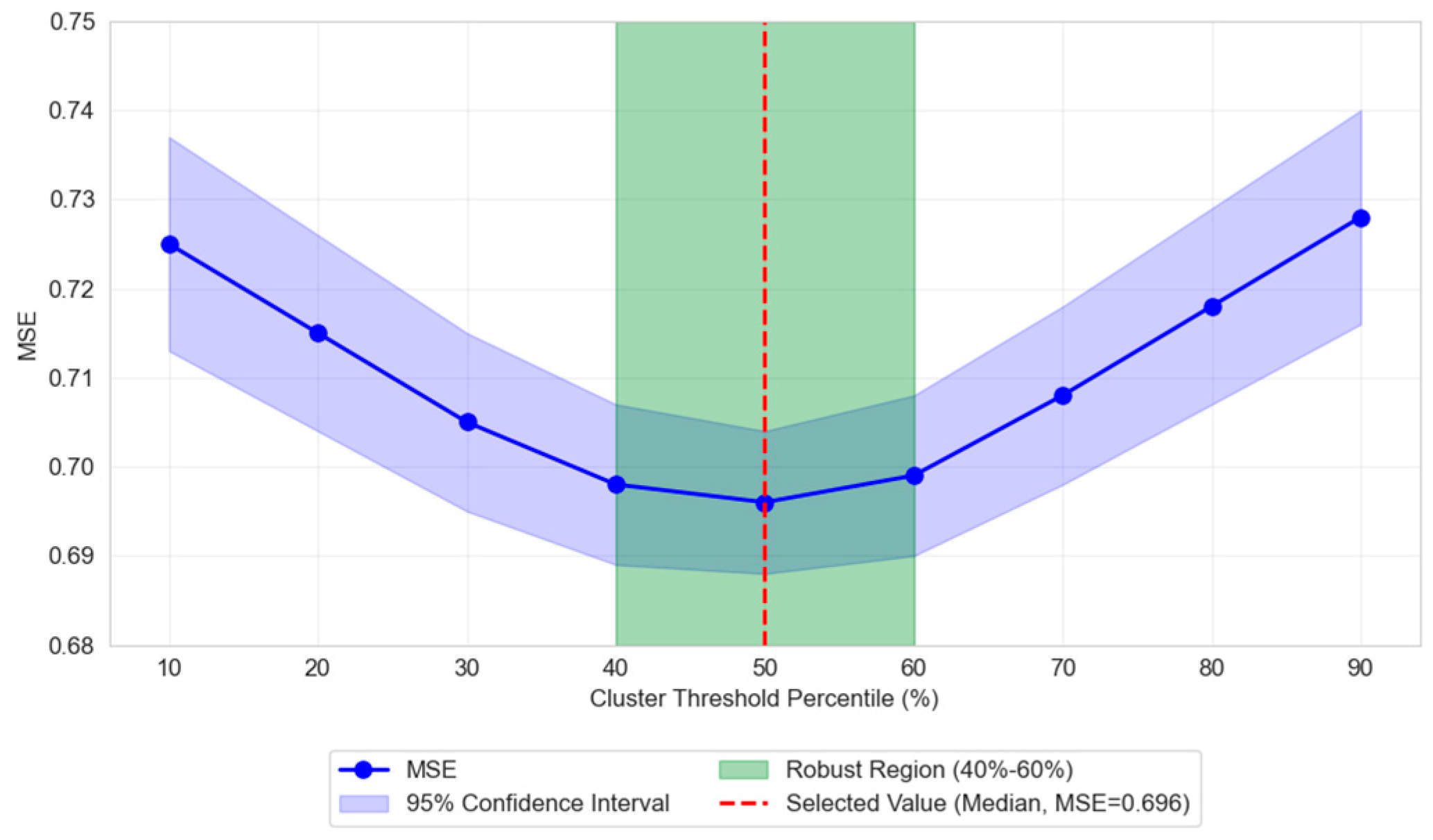

3.3.1. Determination of Clustering Threshold in Vertical Attention

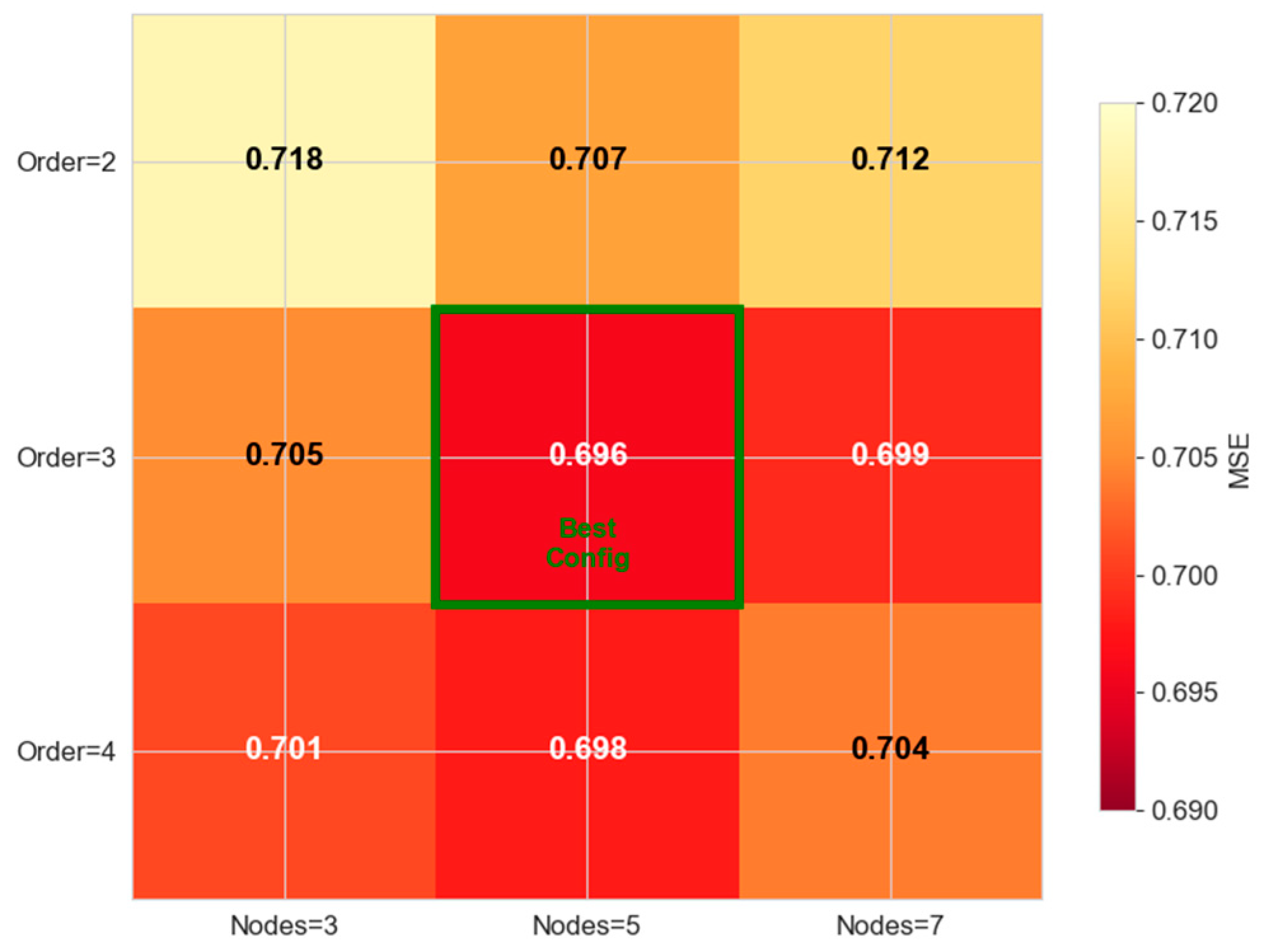

3.3.2. Analysis of B-Spline Configuration in KAN Module

3.4. Ablation Experiment Results

- (1)

- Contribution of the KAN Module: The KAN module delivers the most significant performance gain. Its removal leads to a 6.61% increase in MSE (from 0.696 to 0.742) and a 7.01% increase in MAE (from 0.385 to 0.412). This result verifies the theoretical advantage of applying the Kolmogorov–Arnold decomposition in modeling the nonlinear coupling among UAV state variables. Compared to traditional FFNs with fixed activation functions, the learnable B-spline basis functions in KAN offer more accurate approximations of complex physical couplings, such as those between attitude and wind speed.

- (2)

- Contribution of the Cross-Dimensional Attention Mechanism: The cross-dimensional attention mechanism also provides notable benefits. Its removal results in a 5.17% increase in MSE (from 0.696 to 0.732) and a 4.41% increase in MAE (from 0.385 to 0.402). Further analysis indicates that the vertical attention branch, guided by feature clustering priors (e.g., clustering angular velocity and linear acceleration), explicitly models inter-feature physical correlations. Meanwhile, the horizontal attention branch employs a patch-based dimensionality reduction strategy to capture long-term temporal dependencies effectively. Together, these two branches compensate for the spatiotemporal fusion limitations of standard Transformers.

| Model | Mse (Mean ± 95% CI) | Mae (Mean ± 95% CI) | Significance (Vs. KAN-Former) |

|---|---|---|---|

| KAN-Former | 0.696 ± 0.008 | 0.385 ± 0.007 | - |

| w/o KAN | 0.742 ± 0.009 | 0.412 ± 0.008 | * |

| w/o Cross-Attn | 0.732 ± 0.010 | 0.402 ± 0.009 | * |

3.5. Analysis of Attention Configuration Optimization

- (1)

- Time-First: Horizontal attention is executed first to capture temporal dependencies, and then vertical attention is executed to model feature associations;

- (2)

- Channel-First: Vertical attention is first used to establish feature physical associations, and then horizontal attention is applied to analyze temporal dynamics;

- (3)

- Alternate: Alternating between the two attention mechanisms between network layers.

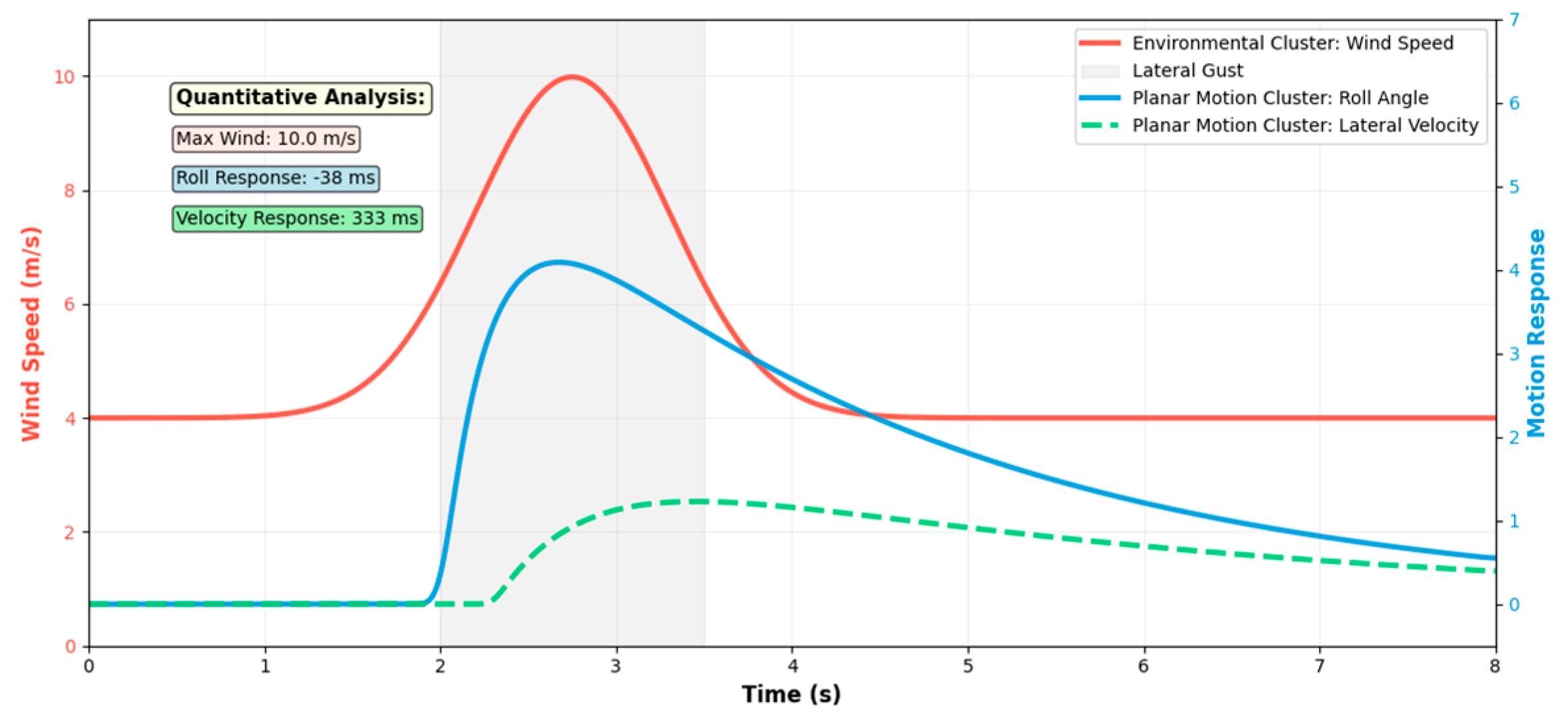

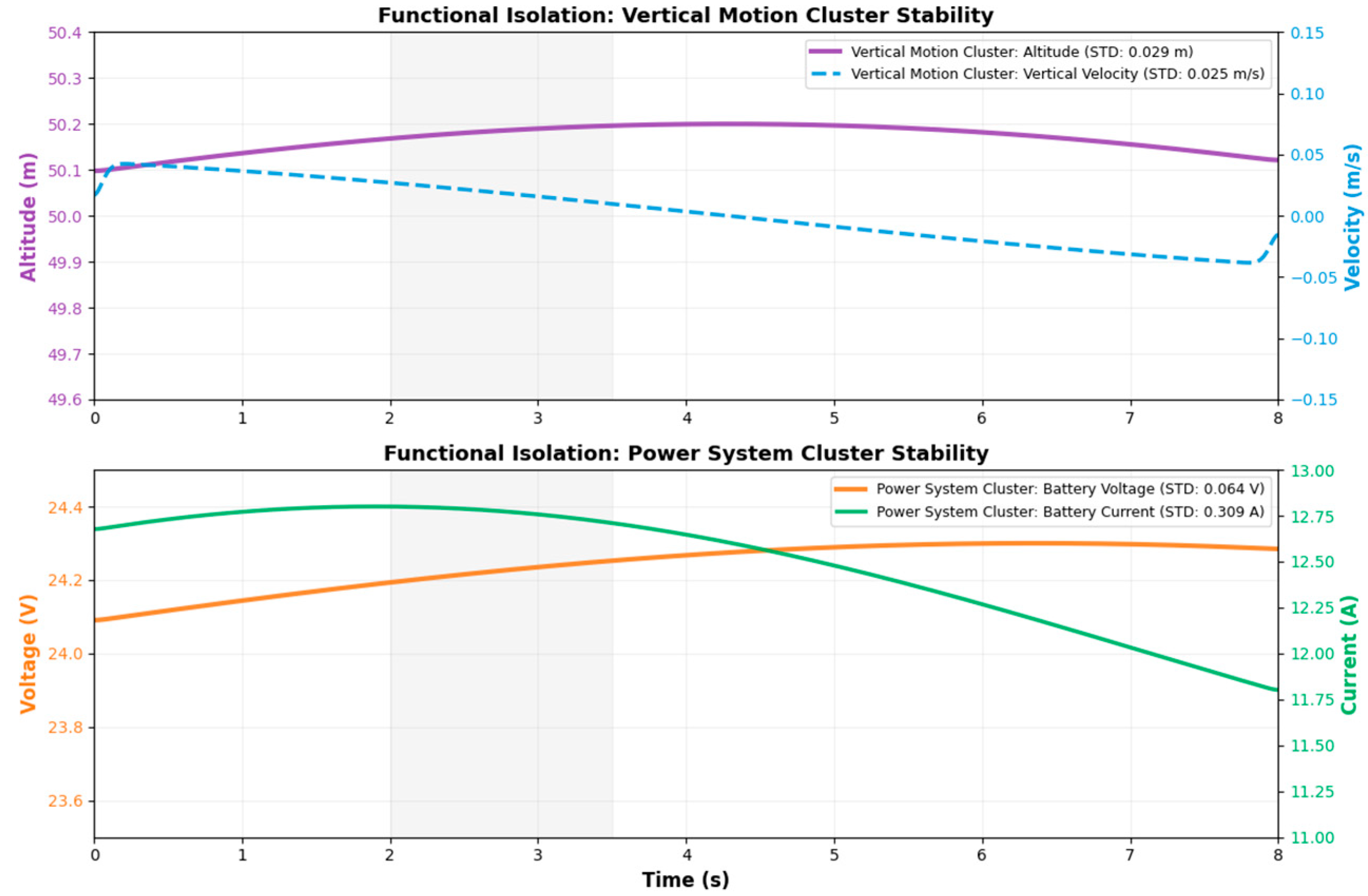

3.6. Interpretability Verification and Analysis of Feature Clustering

3.7. Computational Efficiency Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Simone, M.C.; Russo, S.; Rivera, Z.B.; Guida, D. Multibody Model of a UAV in Presence of Wind Fields. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Control, Artificial Intelligence, Robotics & Optimization (ICCAIRO), Prague, Czech Republic, 20–22 May 2017; pp. 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.J.; Zhang, R.; Gao, G.G.; Xu, B. Cooperative Navigation of UAV Formation Based on Relative Velocity and Position Assistance. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. 2022, 56, 1438–1446. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, S.; Shen, D.; Wang, X.; Han, N. A Self-Adaptive Parameter Selection Trajectory Prediction Approach via Hidden Markov Models. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2014, 16, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, R.; Zuo, J.; Han, D. Trajectory Prediction of Target Aircraft Based on HPSO-TPFENN Neural Network. J. Northwestern Polytech. Univ. 2019, 37, 612–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; McClean, S.I.; Parr, G.; Teacy, L.; De Nardi, R. UAV Position Estimation and Collision Avoidance Using the Extended Kalman Filter. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2013, 62, 2749–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M. Research on Trajectory Prediction Method of Small UAV Based on Track Data. Master’s Thesis, Civil Aviation University of China, Tianjin, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alexis, K.; Nikolakopoulos, G.; Tzes, A. On Trajectory Tracking Model Predictive Control of an Unmanned Quadrotor Helicopter Subject to Aerodynamic Disturbances. Asian J. Control 2014, 16, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Shao, K.; Zhen, S.; Sun, H.; Yu, R. A Novel Approach for Trajectory Tracking Control of an Under-Actuated Quadrotor UAV. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2017, 4, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baklacioglu, T.; Cavcar, M. Aero-Propulsive Modelling for Climb and Descent Trajectory Prediction of Transport Aircraft Using Genetic Algorithms. Aeronaut. J. 2014, 118, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Guo, J.; Shen, Z. Prediction of 4D Trajectory Based on Basic Flight Models. J. Southwest Jiaotong Univ. 2009, 44, 295–300. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, Y.T.; Wang, Y.H.; Liu, Y.M. Probabilistic Aircraft Trajectory Prediction with Weather Uncertainties Using Approximate Bayesian Variational Inference to Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the AIAA Aviation 2020 Forum, Virtual Event, 15–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, C. UAV Trajectory Tracking via RNN-Enhanced IMM-KF with ADS-B Data. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 21–24 April 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Lu, J.; Qin, Z. Aircraft Trajectory Prediction Based on Residual Recurrent Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Electrical Engineering, Big Data and Algorithms (EEBDA), Changchun, China, 24–26 February 2023; pp. 1820–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Xu, M.; Pan, Q.; Yan, B.; Zhang, H. LSTM-Based Flight Trajectory Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 8–13 July 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Yue, J.; Fang, C.; Shi, Q.; Yang, J. Short-Term 4D Trajectory Prediction Based on LSTM Neural Network. Proc. SPIE 2020, 11427, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Yue, J.; Han, P. Short-Term Flight Trajectory Prediction Based on LSTM-ARIMA Model. J. Signal Process. 2019, 35, 2000–2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, L.; Jiang, F.; Peng, Y. Attention-Based UAV Trajectory Optimization for Wireless Power Transfer-Assisted IoT Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 1024–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xu, A. Transformer-Encoder-LSTM for Aircraft Trajectory Prediction. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 128, 107749. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, A.; Luo, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, J. An Improved Transformer-Based Model for Long-Term 4D Trajectory Prediction in Civil Aviation. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 18, 1588–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Wang, S.; Li, R. Trajectory Prediction of Hypersonic Vehicles Based on Adaptive IMM Algorithm. Shanghai Aerosp. 2016, 33, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, Y.; Nguyen, N.H.; Sinthong, P.; Kalagnanam, J. A Time Series is Worth 64 Words: Long-Term Forecasting with Transformers. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palamas, A.; Kolios, P. Drone Onboard Multi-Modal Sensor Dataset. Zenodo, 2023. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/7643456 (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-Based Learning Applied to Document Recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Wu, H.; Shi, X.; Hu, T.; Luo, H.; Ma, L.; Zhang, J.Y.; Zhou, J. TimeMixer: Decomposable Multiscale Mixing for Time Series Forecasting. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.14616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Guan, A.; Cheng, S. Double Decomposition and Fuzzy Cognitive Graph-Based Prediction of Non-Stationary Time Series. Sensors 2024, 24, 7272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Guan, A.; Du, J.; Ayush, A. Multivariate time series prediction with multi-feature analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 268, 126302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Multivariate Modeling | Long-Term Sequence Processing | Nonlinear Approximation |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNN | Implicit recursion | Gradient vanishing (<100 steps) | ) |

| LSTM | Implicit gating mechanism | Partially alleviates gradient vanishing (<500 steps) | ) |

| Transformer | Global self-attention | Parallel computation (theoretically unlimited steps) | ) |

| KAN-Former | Clustering-guided vertical attention | Blockwise dimensionality reduction + horizontal attention | ) |

| Cluster | Size | Features | Potential Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | 4 | orientation_x, orientation_y, linear_acceleration_x, linear_acceleration_y | Environment and Basic State Group: Includes wind speed, battery status, and position coordinates; reflects the UAV’s basic physical state and interaction with the environment. |

| Cluster 2 | 6 | altitude, velocity_z, angular_x, angular_y, angular_z, linear_acceleration_z | Vertical Motion and Rotation Group: Related to altitude, vertical velocity, and angular velocity; represents UAV ascent, descent, and rotational behavior. |

| Cluster 3 | 7 | wind_speed, wind_angle, battery_voltage, battery_current, position_x, position_y, position_z | Environment and Power Status Group: Reflects the influence of environmental conditions and power system state on the UAV’s flight path. |

| Cluster 4 | 4 | orientation_z, orientation_w, velocity_x, velocity_y | Planar Motion and Attitude Group: Combines quaternion components and horizontal velocity to describe the UAV’s posture during planar motion. |

| Optimizer | AdamW | Weight Decay of 0.01 |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Learning Rate | 1 × 10−4 | - |

| Learning Rate Scheduler | Cosine Annealing | T_max = 100, η_min = 1 × 10−6 |

| Batch Size | 64 | Fixed for all experiments |

| Training Epochs | 200 | Maximum number of epochs |

| Early Stopping | 15 | Stop if validation loss does not improve for 15 consecutive epochs |

| Gradient Clipping | 1.0 | Global norm clipping |

| Loss Function | MSE | - |

| Model | Mse (Mean ± 95% CI) | Mae (Mean ± 95% CI) | Significance (Vs. KAN-Former) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNN | 0.852 ± 0.011 | 0.521 ± 0.015 | * |

| LSTM | 0.798 ± 0.014 | 0.478 ± 0.012 | * |

| Transformer | 0.764 ± 0.010 | 0.492 ± 0.009 | * |

| Timemixer | 0.813 ± 0.013 | 0.416 ± 0.011 | * |

| PatchTST | 0.809 ± 0.012 | 0.415 ± 0.010 | * |

| SST | 0.745 ± 0.009 | 0.408 ± 0.008 | * |

| PITA | 0.715 ± 0.008 | 0.391 ± 0.007 | * |

| KAN-Former | 0.696 ± 0.008 | 0.385 ± 0.007 | - |

| Predicted Length T | 96 | 192 | 336 | 720 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attention Allocation Schemes | |||||||||

| Mse | Mae | Mse | Mae | Mse | Mae | Mse | Mae | ||

| Time-First | 0.7661 | 0.4150 | 0.8921 | 0.4751 | 0.9951 | 0.5302 | 1.1027 | 0.5951 | |

| Channel-First | 0.6965 | 0.3852 | 0.8100 | 0.4387 | 0.9105 | 0.4827 | 1.0165 | 0.5435 | |

| Alternate | 0.7313 | 0.4012 | 0.8453 | 0.4526 | 0.9481 | 0.5001 | 1.0535 | 0.5641 | |

| Model | Parameters (M) | Training Time (s/Epoch) | Inference Time (ms) | Mse |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN | 2.1 | 58 | 4.1 | 0.852 |

| LSTM | 3.5 | 152 | 12.5 | 0.798 |

| Transformer | 48.7 | 332 | 25.3 | 0.764 |

| Timemixer | 12.3 | 171 | 14.7 | 0.813 |

| PatchTST | 10.8 | 127 | 11.2 | 0.809 |

| SST | 22.4 | 145 | 10.8 | 0.745 |

| PITA | 18.7 | 203 | 16.2 | 0.715 |

| KAN-Former | 15.6 | 188 | 15.5 | 0.696 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, J.; Lu, Y. KAN-Former: 4D Trajectory Prediction for UAVs Based on Cross-Dimensional Attention and KAN Decomposition. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3877. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233877

Chen J, Lu Y. KAN-Former: 4D Trajectory Prediction for UAVs Based on Cross-Dimensional Attention and KAN Decomposition. Mathematics. 2025; 13(23):3877. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233877

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Junfeng, and Yuqi Lu. 2025. "KAN-Former: 4D Trajectory Prediction for UAVs Based on Cross-Dimensional Attention and KAN Decomposition" Mathematics 13, no. 23: 3877. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233877

APA StyleChen, J., & Lu, Y. (2025). KAN-Former: 4D Trajectory Prediction for UAVs Based on Cross-Dimensional Attention and KAN Decomposition. Mathematics, 13(23), 3877. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233877