Sharp Coefficient Bounds for a Class of Analytic Functions Related to Exponential Function

Abstract

1. Introduction

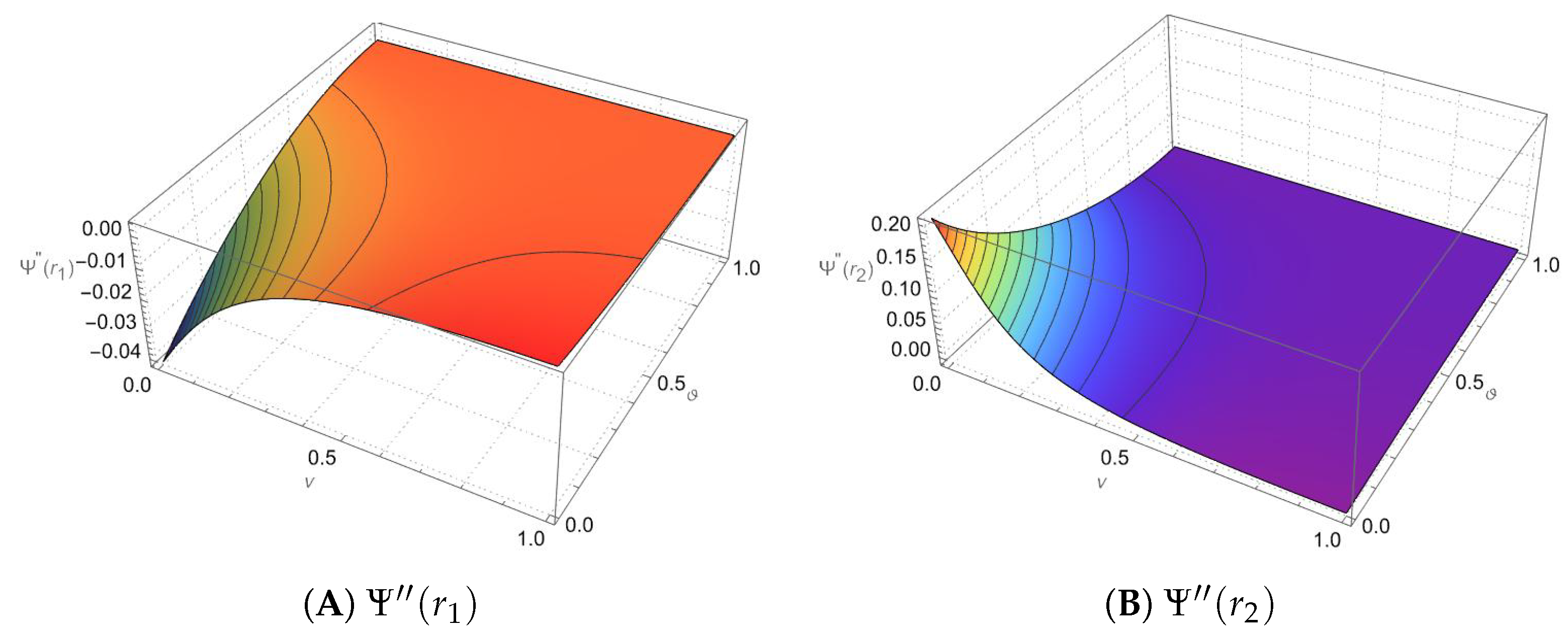

2. Main Results

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, W.C.; Minda, D. A unified treatment of some special classes of univalent functions. In Proceedings of the Conference on Complex Analysis, Tianjin, China, 19–23 June 1992; International Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994; pp. 157–169. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, K.; Jain, N.K.; Ravichandran, V. Starlike functions associated with a cardioid. Afr. Math. 2016, 27, 923–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatter, K.; Ravichandran, V.; Sivaprasad Kumar, S. Starlike functions associated with exponential function and the lemniscate of Bernoulli. Rev. R. Acad. Cienc. Exactas Fís. Nat. Ser. A Math. RACSAM 2019, 113, 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, R.K.; Sharma, P.; Sokół, J. Certain classes of analytic functions related to the crescent-shaped regions. Izv. Nats. Akad. Nauk Armenii Math. 2018, 53, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, Y.; Halim, S.A.; Akbarally, A.B. Subclass of starlike functions associated with a limacon. AIP Conf. Proc. 2018, 1974, 030023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, P.; Kumar, S.S. Certain class of starlike functions associated with modified sigmoid function. Bull. Malays. Math. Sci. Soc. 2019, 42, 2121–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, N.E.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, S.S.; Ravichandran, V. Radius problems for starlike functions associated with the sine function. Bull. Iran. Math. Soc. 2019, 45, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, K.; Srivastava, H.M.; Rafiq, A.; Arif, M.; Arjika, S. A study of sharp coefficient bounds for a new subfamily of starlike functions. J. Inequal. Appl. 2021, 2021, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyah, A.S.; Hadi, S.H.; Wang, Z.-G.; Lupaş, A.A. Classes of Ma–Minda type analytic functions associated with a kidney-shaped domain. AIMS Math. 2025, 10, 22445–22470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyah, A.S.; Atshan, W.G. Starlikeness and Bi-Starlikeness Associated with a New Carathéodory Function. J. Math. Sci. 2025, 290, 232–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Branges, L. A proof of the Bieberbach conjecture. Acta Math. 1985, 154, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pommerenke, C. On the coefficients and Hankel determinants of univalent functions. J. Lond. Math. Soc. 1966, 41, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janteng, A.; Halim, S.A.; Darus, M. Coefficient inequality for a function whose derivative has a positive real part. J. Inequal. Pure Appl. Math. 2006, 7, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Janteng, A.; Halim, S.A.; Darus, M. Hankel determinant for starlike and convex functions. Int. J. Math. Anal. 2007, 1, 619–625. [Google Scholar]

- Obradović, M.; Tuneski, N. Hankel determinants of second and third order for the class S of univalent functions. Math. Slovaca 2021, 71, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradović, M.; Tuneski, N. Two types of the second Hankel determinant for the class U and the general class S. Acta Comment. Univ. Tartu. Math. 2023, 27, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, A.; Raza, M.; Binyamin, M.A.; Saliu, A. The second and third Hankel determinants for starlike and convex functions associated with Three-Leaf function. Heliyon 2023, 9, 12748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaprawa, P. On Hankel determinant H2(3) for univalent functions. Results Math. 2018, 73, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, K.O. On H3(1) Hankel determinant for some classes of univalent functions. In Inequality Theory and Applications; Cho, Y.J., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Volume 6, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zaprawa, P. Third Hankel determinants for subclasses of univalent functions. Mediterr. J. Math. 2017, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, B.; Lecko, A.; Thomas, D.K. The sharp bound of the third Hankel determinant for starlike functions. Forum Math. 2022, 34, 1249–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, B.; Lecko, A. The sharp bound of the third Hankel determinant for functions of bounded turning. Bol. Soc. Math. Mex. 2021, 27, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, B.; Lecko, A.; Sim, Y.J. The sharp bound for the Hankel determinant of the third kind for convex functions. Bull. Aust. Math. Soc. 2018, 97, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banga, S.; Kumar, S.S. The sharp bounds of the second and third Hankel determinants for the class SL*. Math. Slovaca 2020, 70, 849–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecko, A.; Sim, Y.J.; Śmiarowska, B. The sharp bound of the Hankel determinant of the third kind for starlike functions of order 1/2. Complex Anal. Oper. Theory 2019, 13, 2231–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, A.; Raza, M. The third Hankel determinant for starlike and convex functions associated with lune. Bull. Sci. Math. 2023, 187, 103289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyah, A.S.; Hadi, S.H.; Alatawi, A.; Abbas, M.; Bagdasar, O. Sharp Functional Inequalities for Starlike and Convex Functions Defined via a Single-Lobed Elliptic Domain. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, A.; Raza, M.; Thomas, D.K. Hankel determinants for starlike and convex functions associated with sigmoid functions. Forum Math. 2022, 34, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, F.R.; Merkes, E.P. A coefficient inequality for certain classes of analytic functions. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 1969, 20, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efraimidis, I. A generalization of Livingston’s coefficient inequalities for functions with positive real part. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2016, 435, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, V.; Verma, S. Bound for the fifth coefficient of certain starlike functions. C. R. Math. 2015, 353, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pommerenke, C. Univalent Functions; Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht: Göttingen, Germany, 1975. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tayyah, A.S.; Yalçın, S.; Bayram, H. Sharp Coefficient Bounds for a Class of Analytic Functions Related to Exponential Function. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3878. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233878

Tayyah AS, Yalçın S, Bayram H. Sharp Coefficient Bounds for a Class of Analytic Functions Related to Exponential Function. Mathematics. 2025; 13(23):3878. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233878

Chicago/Turabian StyleTayyah, Adel Salim, Sibel Yalçın, and Hasan Bayram. 2025. "Sharp Coefficient Bounds for a Class of Analytic Functions Related to Exponential Function" Mathematics 13, no. 23: 3878. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233878

APA StyleTayyah, A. S., Yalçın, S., & Bayram, H. (2025). Sharp Coefficient Bounds for a Class of Analytic Functions Related to Exponential Function. Mathematics, 13(23), 3878. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233878