Improved Post-Assembly Magnetization Performance of Spoke-Type PMSM Using a 5-Times Divided Magnetizer with Auxiliary Pole Winding

Abstract

1. Introduction

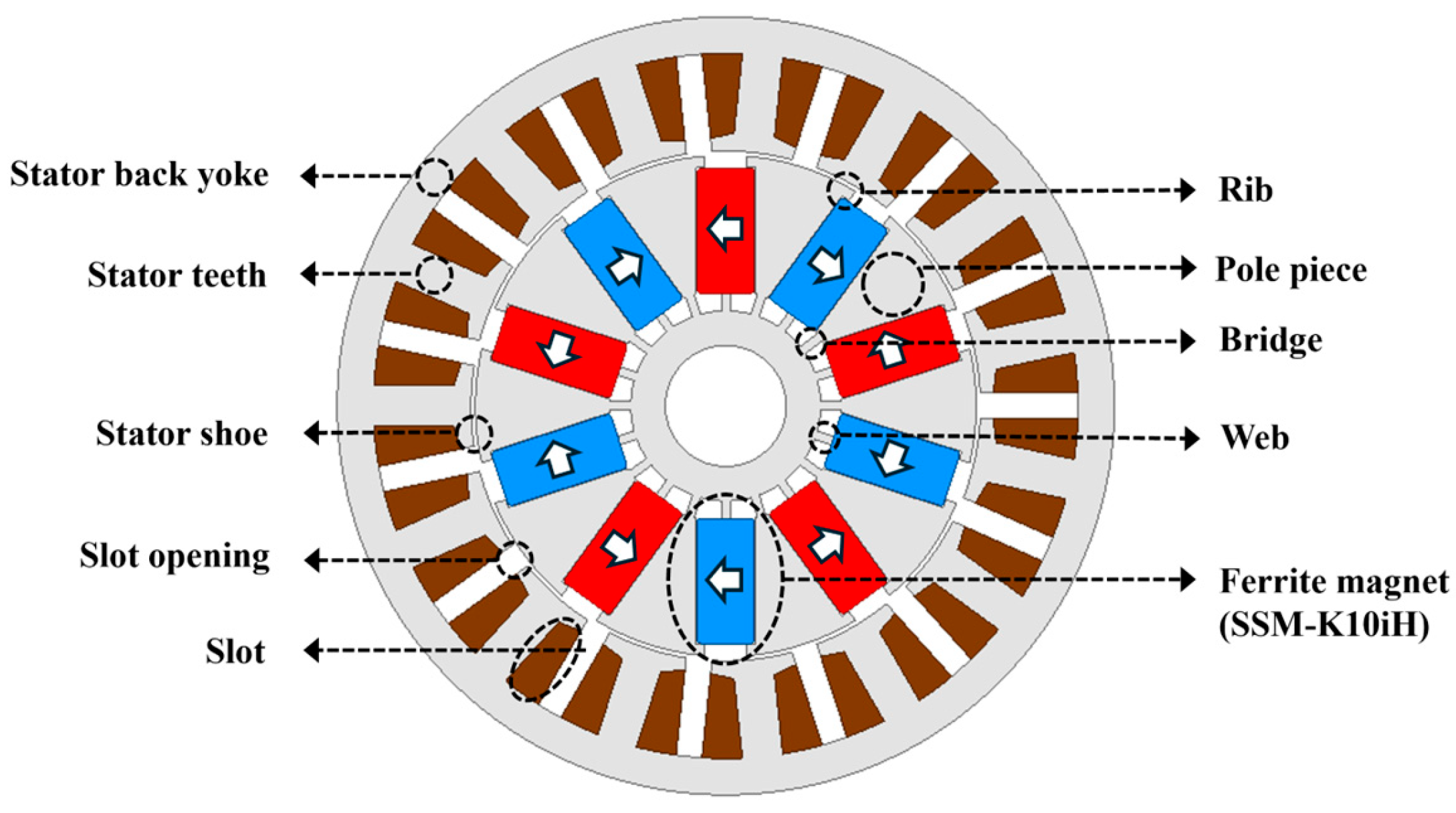

2. Target Spoke-Type Permanent Magnet Motor

Specification of Target Motor

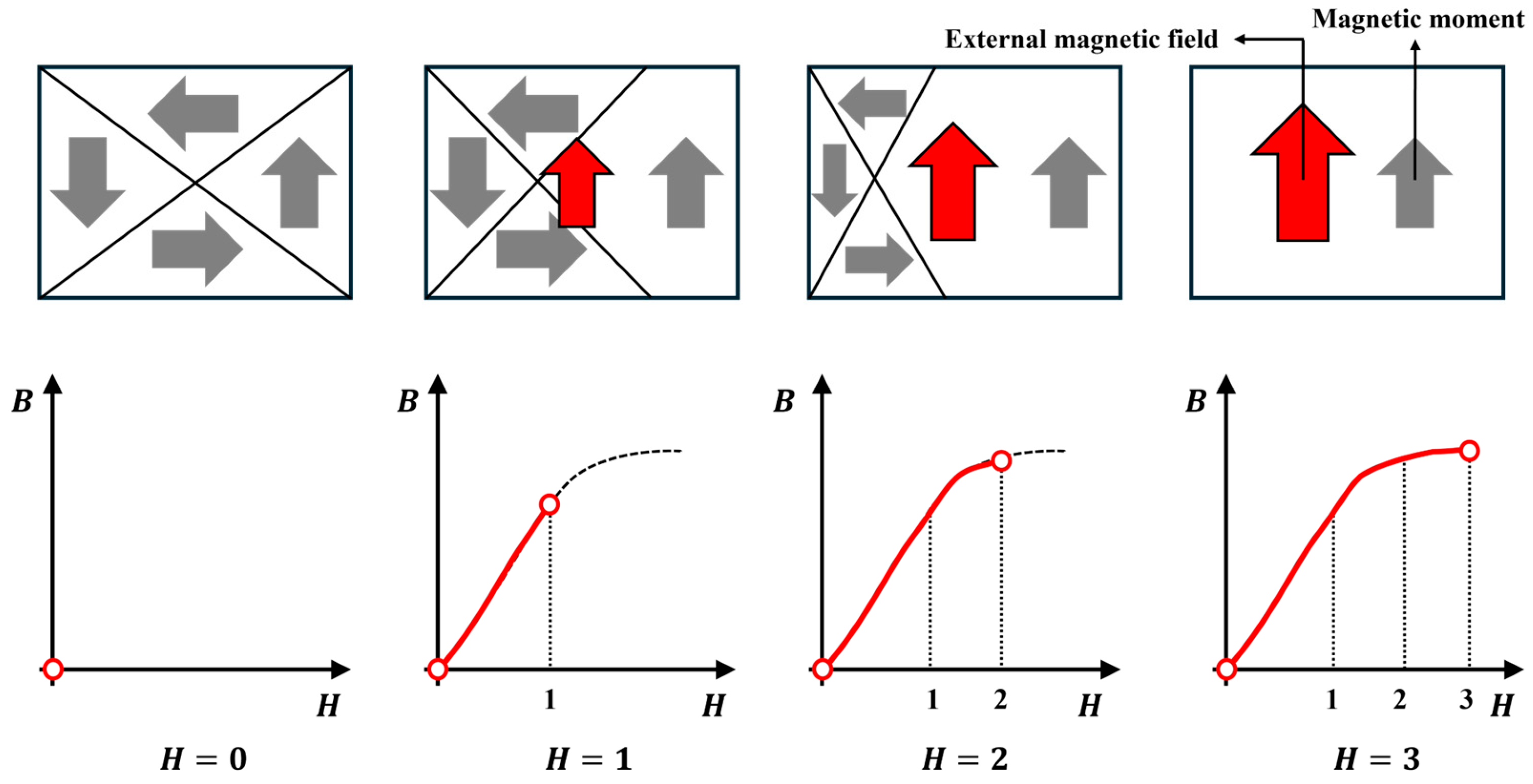

3. Principle of Magnetization and Demagnetization of PM

3.1. Principle of Magnetization

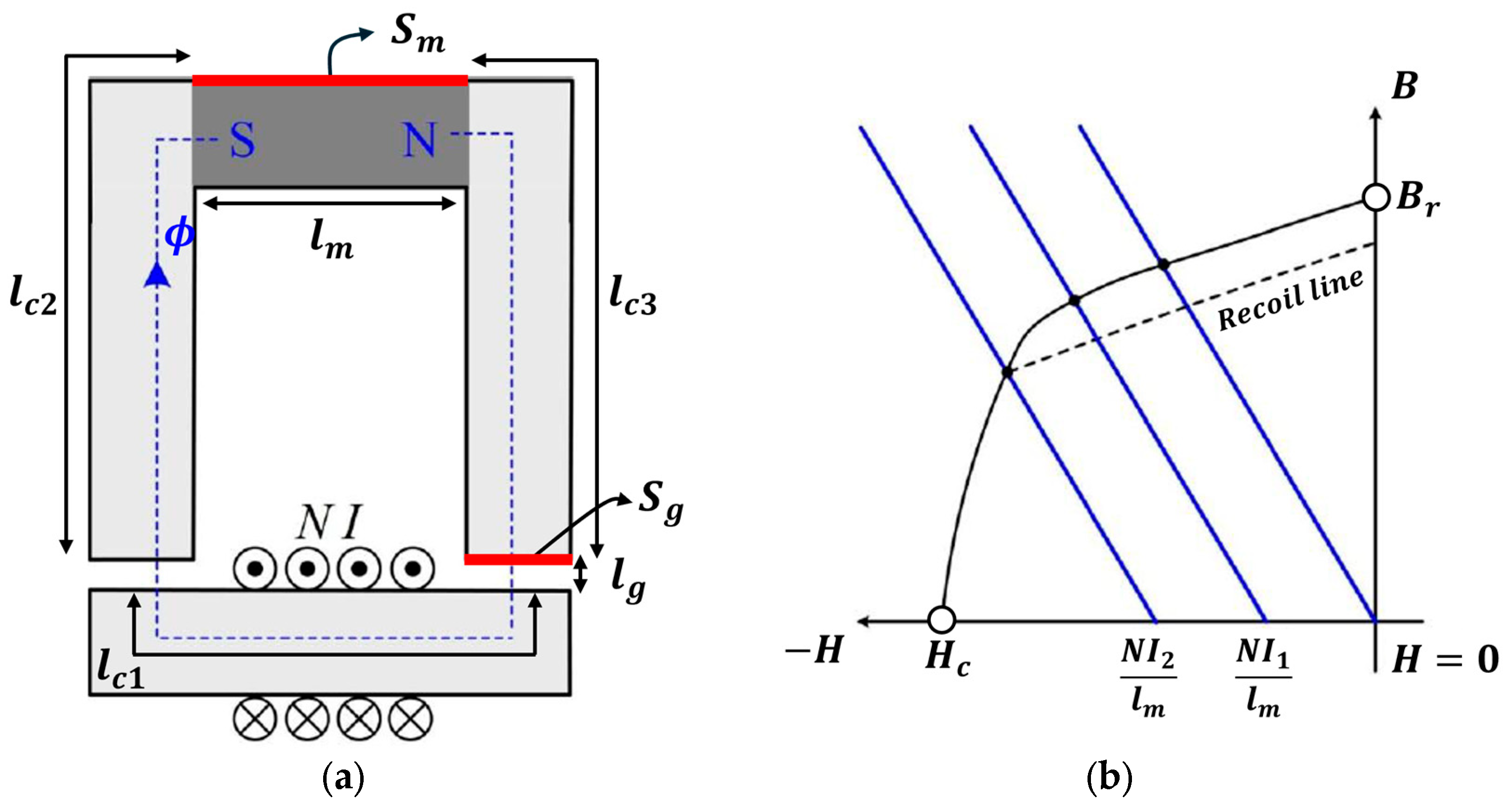

3.2. Principle of Demagnetization

4. Post-Assembly Magnetization Analysis Setup

4.1. Magnetizing System Configuration

4.1.1. Magnetizer Specifications and Electrical Characteristics

4.1.2. Magnetic Properties of Ferrite Magnet

5. Basic Design of Post-Assembly Magnetizing Yoke

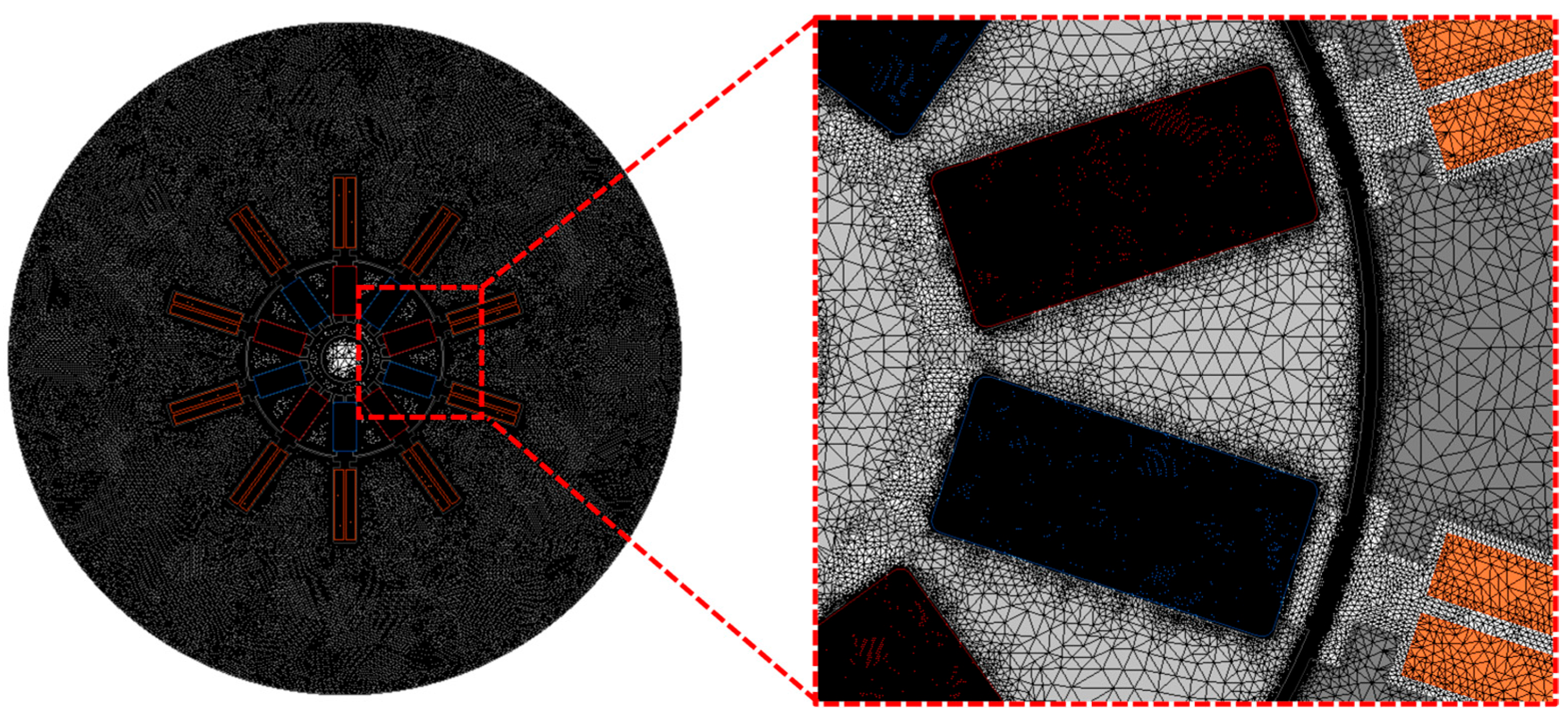

5.1. FEA Results of Post-Assembly Segmented Magnetization Analysis

5.1.1. Modeling of the Magnetizing Yoke

5.1.2. Simulation Verification

5.1.3. FEA Results of Basic Post-Assembly Segmented Magnetization Analysis

6. Post-Assembly 3-Time Magnetization Analysis

6.1. Structure and Principle of Auxiliary Pole

6.2. 3-Time Magnetization Analysis with Applied Auxiliary Pole Winding

7. Proposed Model of Post-Assembly 5-Time Magnetization

7.1. Magnetization Analysis with Applied Auxiliary Pole

7.2. Magnetization Analysis with Applied Auxiliary Pole Winding

7.3. Magnetization Analysis with Proposed Model

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Souza, D.F.; da Silva, P.P.F.; Sauer, I.L.; de Almeida, A.T.; Tatizawa, H. Life cycle assessment of electric motors—A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 456, 142366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, J.; de Wachter, B.; Sangiorgio, I.; Ntaras, N.; Zarkadoula, M.; de Almeida, A.T. Policy recommendations to accelerate the replacement of inefficient electric motors in the EU. Energy Effic. 2025, 18, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podmiljšak, B.; Saje, B.; Jenuš, P.; Tomše, T.; Kobe, S.; Žužek, K.; Šturm, S. The Future of Permanent-Magnet-Based Electric Motors: How Will Rare Earths Affect Electrification? Materials 2024, 17, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Cao, H.; Liu, W. Torque Ripple Suppression of Synchronous Reluctance Motors for Electric Vehicles Based on Rotor Improvement Design. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electr. 2023, 9, 4328–4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y. A Hybrid PM-Assisted SynRM with Ferrite and Rare-Earth Magnets. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 11245–11255. [Google Scholar]

- Heidari, H.; Rassõlkin, A.; Kallaste, A.; Vaimann, T.; Andriushchenko, E.; Belahcen, A.; Lukichev, D.V. A review of synchronous reluctance motor-drive advancements. Sustainability 2021, 13, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Kim, K.-T.; Hur, J. Design and Optimization of Neodymium-Free SPOKE-Type Motor with Segmented Wing-Shaped PM. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2014, 50, 865–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.-W.; Jung, D.-H.; Lee, J. A Study on the Design Method for Improving the Efficiency of Spoke-Type PMSM. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2023, 59, 8200205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, T.; Li, D.; Qu, R.; Jiang, D. Performance Comparison of Surface and Spoke-Type Flux-Modulation Machines with Different Pole Ratios. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2017, 53, 7402605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.-A.; Che, V.-H.; Hsieh, M.-F. Maximization of High-Efficiency Operating Range of Spoke-Type PM E-Bike Motor by Optimization Through New Motor Constant. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2023, 59, 1328–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasil, M.; Mijatovic, N.; Jensen, B.B.; Holboll, J. Performance Variation of Ferrite Magnet PMBLDC Motor with Temperature. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2015, 51, 8115106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seol, H.-S.; Jeong, T.-C.; Jun, H.-W.; Lee, J.; Kang, D.-W. Design of 3-Times Magnetizer and Rotor of Spoke-Type PMSM Considering Post-Assembly Magnetization. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2017, 53, 8208005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.-J.; Lee, K.-B.; Song, S.-W.; Lee, S.-H.; Kim, W.-H. A Study on Magnetization Yoke Design for Post-Assembly Magnetization Performance Improvement of a Spoke-Type Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. Machines 2023, 11, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M.-F.; Lien, Y.-M.; Dorrell, D.G. Post-Assembly Magnetization of Rare-Earth Fractional-Slot Surface Permanent-Magnet Machines Using a Two-Shot Method. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2011, 47, 2478–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S.; Park, M.R.; Kim, H.J.; Chai, S.H.; Hong, J.P. Estimation of Rotor Type Using Ferrite Magnet Considering the Magnetization Process. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2016, 52, 8101804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-H.; Hsieh, M.-F. Swiveling Magnetization for Anisotropic Magnets for Variable Flux Spoke-Type Permanent Magnet Motor Applied to Electric Vehicles. Energies 2022, 15, 3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimiabeigi, M.; Widmer, J.D.; Long, R.; Gao, Y.; Goss, J.; Martin, R.; Lisle, T.; Vizan, J.M.; Michaelides, A.; Mecrow, B.C. On selection of rotor support material for a ferrite magnet spoke-type traction motor. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2016, 52, 2224–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value | Unit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size | Outer/Inner diameter of stator | 90/59 | mm |

| Outer/Inner diameter of rotor | 58/14 | ||

| Stack length | 90 | ||

| Material | Stator/Rotor | 50PN470 | - |

| Coil | Copper | ||

| Magnet | Ferrite (SSM-K10iH) | ||

| Shaft | SUS303 | ||

| Specification | Pole/Slot | 10/15 | - |

| Voltage | 380 | V | |

| No-load back-EMF (@3600 rpm) | 165.4 | Vrms | |

| Phase current | 1.7 | Arms | |

| Torque (@3600 rpm) | 2.1 | N·m | |

| Efficiency (@3600 rpm) | 91.9 | % |

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Magnetizing yoke core | 50PN470 | - |

| Magnet | Ferrite (SSM-K10iH) | - |

| Maximum charging voltage | 3500 | V |

| Maximum condenser capacity | 3000 | µF |

| Magnetizing yoke inner/outer diameter | 59/200 | mm |

| Outer diameter of winding (Bared/double-edge chamfered) | 2.6 | mm |

| Magnetizing field | 555 | kA/m |

| Demagnetization field | −365 | kA/m |

| Maximum allowable peak current | 14 | kA |

| Parameter | 1 Turns | 2 Turns | 3 Turns | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum applied peak current | 14,300 | 14,000 | 13,700 | Apeak |

| Post-assembly magnetization rate | 99.5 | 99 | 95.7 | % |

| Irreversible demagnetization rate | 9.7 | 6.2 | 4.1 | % |

| Parameter | 2 Turns | 3 Turns | 4 Turns | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum applied peak current | 13,300 | 12,900 | 12,200 | Apeak |

| Post-assembly magnetization rate | 99.7 | 99.2 | 94.1 | % |

| Irreversible demagnetization rate | 2.1 | 0.5 | 0 | % |

| Parameter | 3 Turns | 4 Turns | 5 Turns | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum applied peak current | 12,700 | 12,100 | 11,600 | Apeak |

| Post-assembly magnetization rate | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.5 | % |

| Irreversible demagnetization rate | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0 | % |

| Parameter | 2000 V | 2500 V | 3000 V | 3500 V | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum applied peak current | 6500 | 8200 | 9900 | 11,600 | Apeak |

| Post-assembly magnetization rate | 87.2 | 98.3 | 99.3 | 99.5 | % |

| Irreversible demagnetization rate | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | % |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S.-H.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, W.-H. Improved Post-Assembly Magnetization Performance of Spoke-Type PMSM Using a 5-Times Divided Magnetizer with Auxiliary Pole Winding. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3866. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233866

Lee S-H, Kim J-H, Kim W-H. Improved Post-Assembly Magnetization Performance of Spoke-Type PMSM Using a 5-Times Divided Magnetizer with Auxiliary Pole Winding. Mathematics. 2025; 13(23):3866. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233866

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Seung-Heon, Jong-Hyun Kim, and Won-Ho Kim. 2025. "Improved Post-Assembly Magnetization Performance of Spoke-Type PMSM Using a 5-Times Divided Magnetizer with Auxiliary Pole Winding" Mathematics 13, no. 23: 3866. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233866

APA StyleLee, S.-H., Kim, J.-H., & Kim, W.-H. (2025). Improved Post-Assembly Magnetization Performance of Spoke-Type PMSM Using a 5-Times Divided Magnetizer with Auxiliary Pole Winding. Mathematics, 13(23), 3866. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233866