How Far Can We Trust Chaos? Extending the Horizon of Predictability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Computation of Chaos

3. Computation of the Logistic Map

4. Recursive Computation of the Logistic Map

5. Analytic Computation of the Logistic Map

6. Error-Free Computation of the Logistic Map

7. Conclusions

- We provide a way for generating error-free time series of the Logistic map (Section 6), which can serve as a “gold standard” for testing computation algorithms, since they have effectively unlimited horizons of predictability.

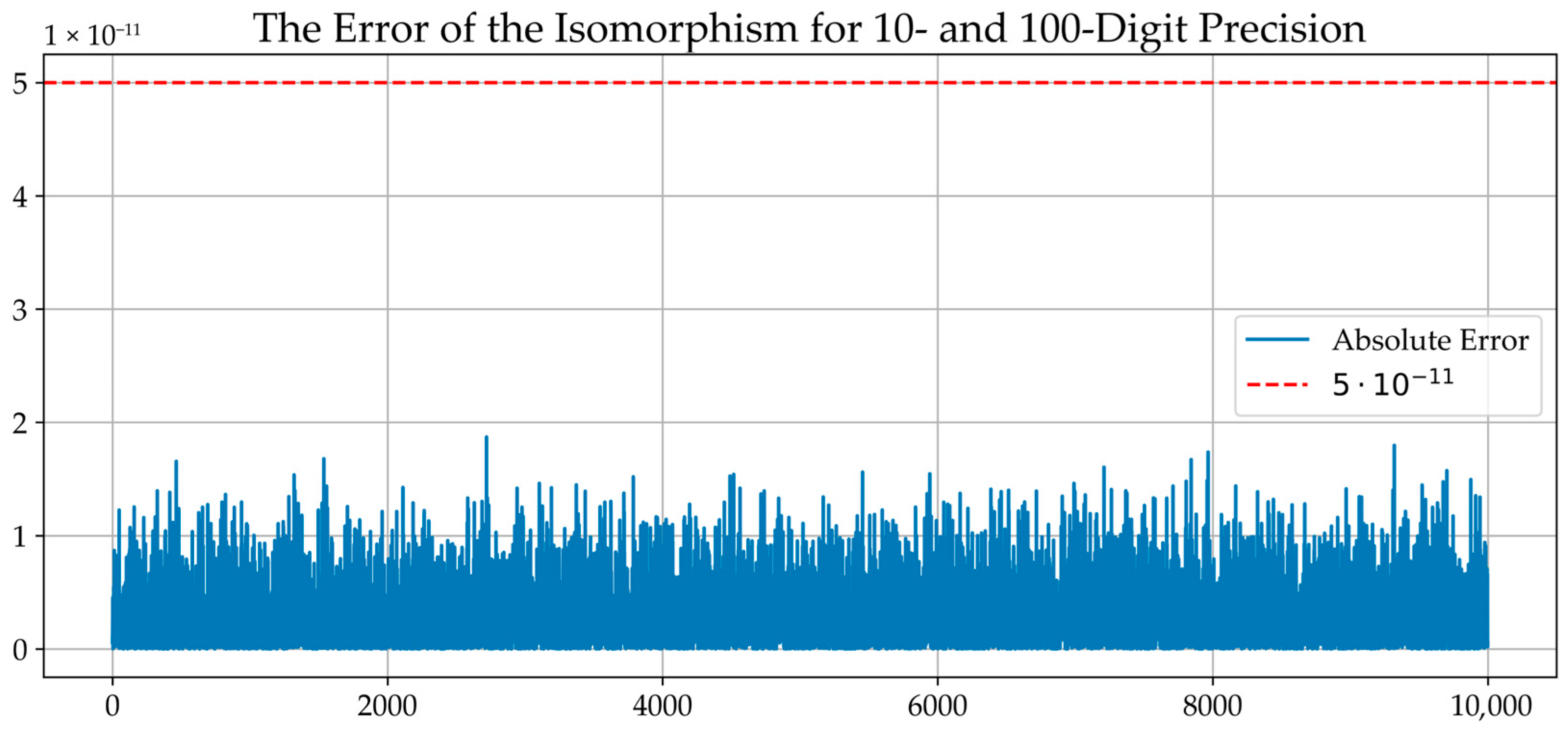

- The proposed Error-Free Computation framework can be generalized to other chaotic maps that admit analytic conjugacies with the Tent map, provided that the error remains bounded (as in Proposition 2) for the conjugation isomorphism. This is confirmed for Chebyshev maps (Appendix F).

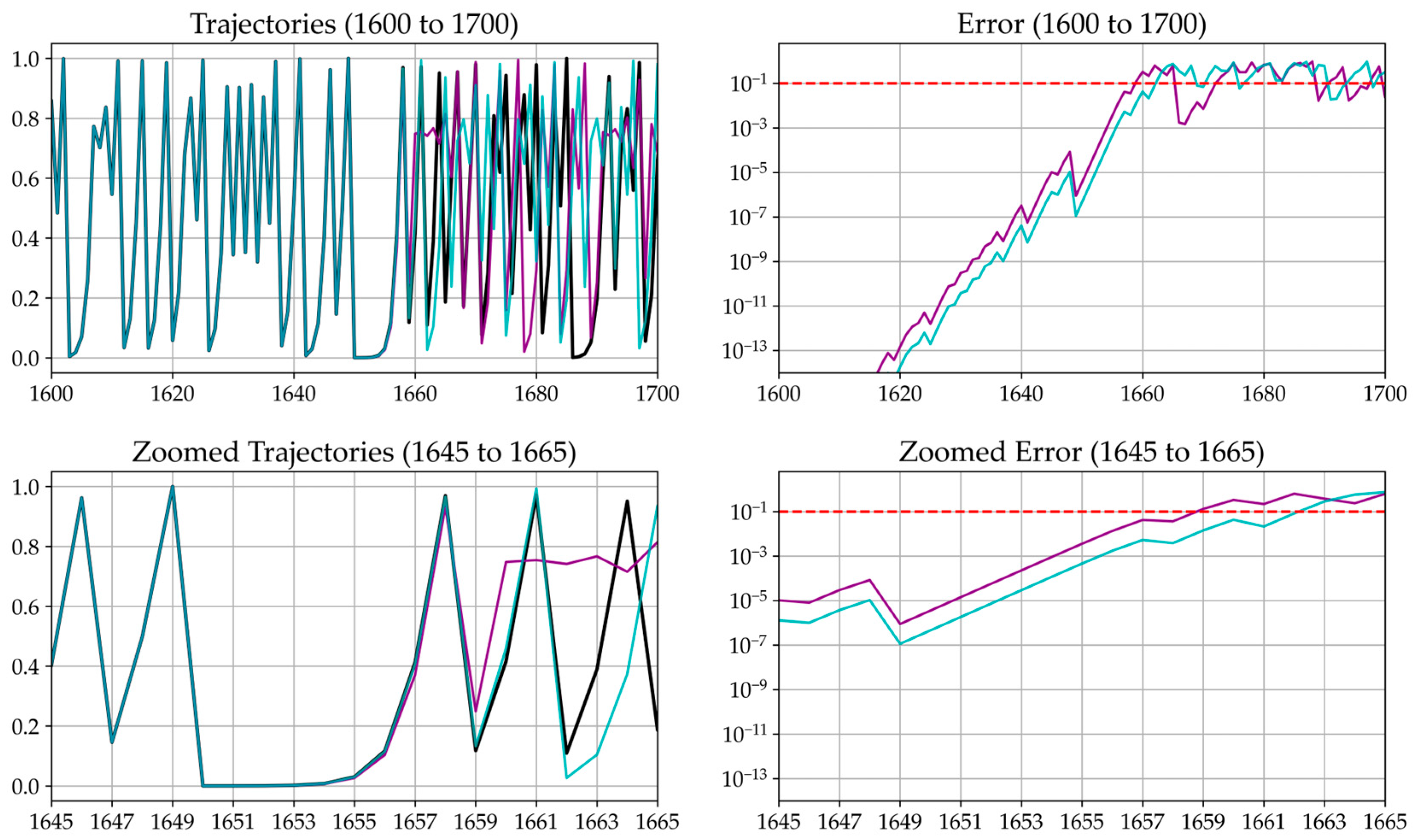

- We introduced and validated a novel formula for the horizon of predictability of the Analytic Computation, Equation (11), of Proposition 1, Section 5, which allows us to find how many iterations we can trust using specific precision and acceptable error. No estimation of the horizon of predictability for the Analytic Computation is found. Only estimations for the Recursive Computation [91,92,93] are available.

- It is surprising that the Analytic Computations are not more reliable than the Recursive Computations. This is explained in Remark 2 and confirmed numerically in Section 6. However, constructing the Analytic Computations demands significantly more resources and time than the Recursive Computations (Appendix G). The duration of the Error-Free Computations is also included in Appendix G for comparison and completeness.

- Significance of our findings:

- Neural networks have been applied to the identification for the analysis of chaotic systems [95,96,97,98]. The ability to compute error-free chaotic orbits allows for comparing the performance of neural networks designed to predict chaotic time series [99]. Both Analytic and Recursive Computations are reliable up to approximately iterations. Therefore, pseudorandom generators constructed from Recursive and Analytic Computations give irrelevant (contaminated) but reproducible time series with machines using the same mantissa and settings. We expect that neural networks will also learn the irrelevant (contaminated) time series.

- The Logistic map has been applied to encryption [100,101,102,103]. However, due to finite numerical precision, the orbits of digital chaotic systems can degrade and become periodic, which compromises the security of chaos-based schemes [104,105,106]. As maintaining the chaotic strength in the master system is crucial for information encryption, the reproducibility of chaotic time series is necessary. This is guaranteed if the mantissa and settings are included in the encryption key.

- The extension of the horizon of predictability challenges the very limits of what can be “trusted” in applications involving chaotic economic models [107]. In markets where price evolution is chaotic, the horizon of predictability (duration of reliable predictions) indicates the bound of rationality. Beyond the horizon of predictability, we have to resort to speculations. The extension of the horizon of predictability has profound implications for the reliable forecasting of future prices in economics [108], Industrial Organization, and Game Theory [109], as well as in Financial Markets [110,111].

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Error-Free Computation of the Tent Map

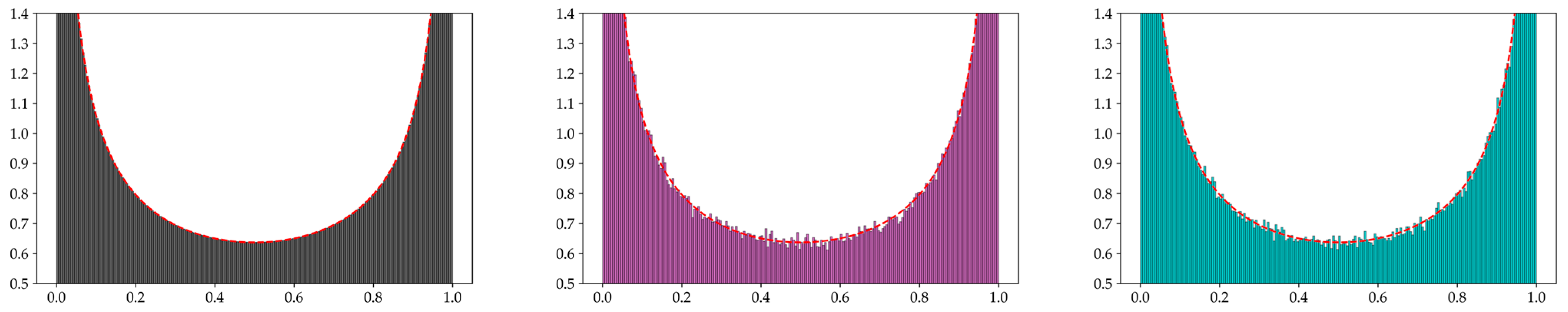

Appendix B. Invariant Measure of the Logistic Map

Appendix C. Numerical Confirmation of Proposition 2 for Several Values of Precision

| Maximum Computation | Theoretical Bound | |

|---|---|---|

Appendix D. Horizons of Predictability of the Logistic Map for Different Precisions

| Horizon of Predictability Equation (11) | Horizon of Predictability of | Horizon of Predictability of | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 1644 | 1648 | 1645 |

| 1000 | 3305 | 3312 | 3311 |

| 1500 | 4966 | 4970 | 4968 |

| 2000 | 6627 | 6631 | 6630 |

| 2500 | 8288 | 8292 | 8292 |

| 3000 | 9949 | 9955 | 9951 |

| 3500 | 11,610 | 11,614 | 11,613 |

| 4000 | 13,271 | 13,277 | 13,276 |

| 4500 | 14,932 | 14,937 | 14,940 |

| Horizon of Predictability Equation (11) | Horizon of Predictability of | Horizon of Predictability of | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 1628 | 1632 | 1630 |

| 1000 | 3289 | 3300 | 3293 |

| 1500 | 4950 | 4954 | 4951 |

| 2000 | 6611 | 6615 | 6614 |

| 2500 | 8272 | 8275 | 8276 |

| 3000 | 9933 | 9939 | 9934 |

| 3500 | 11,594 | 11,598 | 11,595 |

| 4000 | 13,254 | 13,260 | 13,259 |

| 4500 | 14,915 | 14,920 | 14,924 |

Appendix E. Comparison of Computations of the Logistic Map

Appendix F. Error-Free Computation of the Chebyshev Maps

Appendix G. Duration of Computations

| Analytic Computation Time (sec) | Recursive Computation Time (sec) | Error-Free Computation Time (sec) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.5925 | 0.0560 | 0.269 |

| 50 | 0.6456 | 0.0591 | 0.315 |

| 100 | 0.7496 | 0.0661 | 0.411 |

| 500 | 1.9056 | 0.0976 | 1.509 |

| 1000 | 5.2105 | 0.1656 | 4.720 |

| 2000 | 17.1838 | 0.3663 | 16.674 |

| 3000 | 34.6498 | 0.6180 | 35.086 |

| 4000 | 64.6574 | 0.9803 | 63.270 |

| 5000 | 101.4753 | 1.4061 | 102.459 |

| 6000 | 132.6286 | 1.7080 | 142.856 |

| 7000 | 188.9581 | 2.2119 | 190.269 |

| 8000 | 245.5608 | 2.7399 | 252.786 |

| 9000 | 319.0776 | 3.3999 | 321.712 |

| 10,000 | 401.6651 | 4.0490 | 401.906 |

| 11,000 | 433.3804 | 4.3628 | 451.649 |

| 12,000 | 518.4341 | 4.9142 | 575.138 |

| 13,000 | 615.9455 | 5.8450 | 616.429 |

| 14,000 | 741.0641 | 6.5411 | 746.163 |

| 15,000 | 863.7403 | 7.2908 | 872.810 |

References

- Poincaré, H. Les Méthodes Nouvelles de la Mécanique Céleste; Gauthier-Villars et Fils: Paris, France, 1893; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzelli, F. The Essence of Chaos, 1st ed.; CRC Press: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, E.N. Computational chaos-a prelude to computational instability. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 1989, 35, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, E.N. Computational periodicity as observed in a simple system. Tellus A Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 2006, 58, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenberg, A.J.; Lieberman, M.A. Regular and Chaotic Dynamics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaney, R.L. An Introduction to Chaotic Dynamical Systems, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hilborn, R.C. Chaos and Nonlinear Dynamics: An Introduction for Scientists and Engineers, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Strogatz, S.H. Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos: With Applications to Physics, Biology, Chemistry, and Engineering, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Eckmann, J.P.; Ruelle, D. Ergodic theory of chaos and strange attractors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1985, 57, 617–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, F.C. Chaotic and Fractal Dynamics; A Wiley-Interscience Publication; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Alligood, K.; Sauer, T.; Yorke, J. Chaos, An Introduction to Dynamical Systems; Springer Science+Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, E. Chaos in Dynamical Systems, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, C. Dynamical Systems: Stability, Symbolic Dynamics, and Chaos; CRC press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lighthill, M.J. The recently recognized failure of predictability in Newtonian dynamics. Proc. R. Soc. London A Math. Phys. Sci. 1986, 407, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S. On the reliability of computed chaotic solutions of non-linear differential equations. Tellus A Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 2008, 61, 550–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.H.; Barrio, R.; Borwein, J.M. High-precision computation: Mathematical physics and dynamics. Appl. Math. Comput. 2012, 218, 10106–10121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.H.; Jonathan, M.B. High-Precision Arithmetic in Mathematical Physics. Mathematics 2015, 3, 337–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangiorgio, M.; Dercole, F.; Guariso, G. Deep Learning in Multi-Step Prediction of Chaotic Dynamics, From Deterministic Models to Real-World Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, A. New Metric Invariant of Transitive Dynamical Systems and Endomorphisms of Lebesgue Spaces. Dokl. Russ. Acad. Sci. 1958, 119, 861–864. [Google Scholar]

- Billingsley, P. Ergodic Theory and Information; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Cornfeld, I.P.; Fomin, S.F.; Sinai, Y.G. Ergodic Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Pesin, Y. Characteristic Lyapunov Exponents and Smooth Ergodic Theory. Russ. Math. Surv. 1977, 32, 55–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mane, R. A proof of Pesin’s formula. Ergod. Theory Dyn. Syst. 1981, 1, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokhlin, V. Exact endomorphisms of a Lebesgue space. Izv. Akad. Nauk. SSSR Ser. Mat. 1961, 25, 499–530. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, W. On Rohlin’s Formula for Entropy. Acta Math. Hung. 1964, 15, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. When Chaos Meets Computers. arXiv 2004, arXiv:nlin/0405038. [Google Scholar]

- Mali, O.; Neittaanmäki, P.; Repin, S. Errors Arising in Computer Simulation Methods. In Accuracy Verification Methods; Computational Methods in Applied Sciences, vol 32; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boghosian, B.M.; Coveney, P.; Wang, H. A New Pathology in the Simulation of Chaotic Dynamical Systems on Digital Computers. Adv. Theory Simul. 2019, 2, 1900125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coveney, P.V. Sharkovskii’s theorem and the limits of digital computers for the simulation of chaotic dynamical systems. J. Comput. Sci. 2024, 83, 102449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, R.T.; Krishnamurthy, E.V. Methods and Applications of Error-Free Computation; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, P.M.; Jensen, R.V. Simulating chaotic behavior with finite-state machines. Phys. Rev. A 1986, 34, 4460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, C.; Roepstorff, G. Effects of phase space discretization on the long-time behavior of dynamical systems. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 1987, 25, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebogi, C.; Ott, E.; Yorke, J.A. Roundoff-induced periodicity and the correlation dimension of chaotic attractors. Phys. Rev. A 1988, 38, 3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, M. Pathologies generated by round-off in dynamical systems. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 1994, 78, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, P.; Kloeden, P.; Pokrovskii, A. An invariant measure arising in computer simulation of a chaotic dynamical system. J. Nonlinear Sci. 1994, 4, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, P.; Kloeden, P.; Pokrovskii, A.; Vladimirov, A. Collapsing effects in numerical simulation of a class of chaotic dynamical systems and random mappings with a single attracting centre. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 1995, 86, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, G.; Mou, X. On the dynamical degradation of digital piecewise linear chaotic maps. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2005, 15, 3119–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Liao, S. On the risks of using double precision in numerical simulations of spatio-temporal chaos. J. Comput. Phys. 2020, 418, 109629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Den, B.M.; Aldosary, S.; Khaled, H.; Hassan, T.M.; Raslan, W. Leveraging Finite-Precision Errors in Chaotic Systems for Enhanced Image Encryption. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 176057–176069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigogine, I. From Being to Becoming; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou, I.; Tasaki, S. Generalized Spectral Decompositions of Mixing Dynamical Systems. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 1993, 46, 425–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, I.; Tasaki, S. Spectral Decompositions of the Renyi Map. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 1993, 26, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasaki, S.; Antoniou, I.; Suchanecki, Z. Spectral Decomposition and Fractal Eigenvectors for a Class of Piecewise Linear Maps. Chaos Solitons Fractals 1994, 4, 227–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, I.; Qiao, B. Spectral Decomposition of the Tent Maps and the Isomorphism of Dynamical Systems. Phys. Lett. A 1996, 215, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, B.; Antoniou, I. Spectral Decomposition of the Chebyshev Maps. Phys. A 1996, 233, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchanecki, Z.; Antoniou, I.; Tasaki, S.; Bantlow, O. Rigged Hilbert Spaces for Chaotic Dynamical Systems. J. Math. Phys. 1996, 37, 5837–5847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, I.; Qiao, B. Spectral decomposition of the chaotic logistic map. Nonlinear World 1997, 4, 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou, I.; Qiao, B.; Suchanecki, Z. Generalized Spectral Decomposition and Intrinsic Irreversibility of the Arnold Cat Map. Chaos Solitons Fractals 1997, 8, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandtlow, O.F.; Antoniou, I.; Suchanecki, Z. Resonances of Dynamical Systems and Fredholm-Riesz Operators on Rigged Hilbert Space. Comput. Math. Appl. 1997, 34, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, I.; Suchanecki, Z. The Fuzzy Logic of Chaos and Probabilistic Inference. Found. Phys. 1997, 27, 333–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, I.; Gustafson, K. From Irreversible Markov Semigroups to Chaotic Dynamics. Phys. A 1997, 236, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, I.; Gustafson, K.; Suchanecki, Z. On the Inverse Problem of Statistical Physics: From Irreversible Semigroups to Chaotic Dynamics. Phys. A 1998, 252, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, I.; Sadovnichii, V.; Shkarin, S. Time Operators and Shift Representation of Dynamical Systems. Phys. A 1999, 299, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, I.; Melnikov, Y.; Shkarin, S.; Suchanecki, Z. Extended Spectral Decompositions of the Renyi Map. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 2000, 11, 393–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalnay, E.; Modeling, A. Data Assimilation and Predictability; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evensen, G. The Ensemble Kalman Filter: Theoretical formulation and practical implementation. Ocean Dyn. 2003, 53, 343–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasota, A.; Mackey, M.C. Chaos, Fractals, and Noise: Stochastic Aspects of Dynamics; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 97. [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou, I.; Gialampoukidis, I.; Ioannidis, E. Age and Time Operator of Evolutionary Processes. In Quantum Interaction. QI 2015; Atmanspacher, H., Filk, T., Pothos, E., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science(); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 9535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidis, A.K.; Goulas, K.; Bratsas, C.; Makris, G.C.; Hanias, M.P.; Stavrinides, S.G.; Antoniou, I.E. Distinction of Chaos from Randomness Is Not Possible from the Degree Distribution of the Visibility and Phase Space Reconstruction Graph. Entropy 2024, 26, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. Models of Man: Social and Rational; Mathematical Essays on Rational Human Behavior in Society Setting; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Klaes, M.; Sent, E.M. A Conceptual History of the Emergence of Bounded Rationality. Hist. Political Econ. 2005, 37, 27–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, N.C.; Doria, F.A. Undecidability and incompleteness in classical mechanics. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 1991, 30, 1041–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour-El, M.B.; Richards, J.I. Computability in Analysis and Physics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulam, S.M.; von Neumann, J. On Combination of Stochastic and Deterministic Processes. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 1947, 53, 1120. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, P.R.; Ulam, S.M. Non-linear transformation studies on electronic computers. Rozpr. Mat. 1964, 39, 1–66. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya, T.; Szabo, A.; Saitô, N. Exact Solutions of Simple Nonlinear Difference Equation Systems that show Chaotic Behavior. Z. Für Naturforschung A 1983, 38, 1035–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsura, S.F.W. Exactly solvable models showing chaotic behavior. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 1985, 130, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ñustes, M.A.; Hernández-García, E.; González, J.A. Universal functions and exactly solvable chaotic systems. São Paulo J. Math. Sci. 2008, 2, 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Corless, R.M.; Essex, C.; Nerenberg, M.A.H. Numerical methods can suppress chaos. Phys. Lett. A 1991, 157, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corless, R.M. What good are numerical simulations of chaotic dynamical systems? Comput. Math. Appl. 1994, 28, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yao, L.-S. Computed chaos or numerical errors. Nonlinear Anal. Model. Control 2010, 15, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacson, V.E.; Keller, H. Analysis of Numerical Methods; Dover, New Yorl edition of the original 1966 edition; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lozi, R. Can we trust in numerical computations of chaotic solutions of dynamical systems? In Topology and Dynamics of Chaos: In Celebration of Robert Gilmore’s 70th Birthday; World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd: Singapore, 2013; pp. 63–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Liao, S. Influence of numerical noises on computer-generated simulation of spatio-temporal chaos. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 136, 109790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkovskii, A. Coexistence of cycles of a continuous map of a line to itself. Ukr. Mat. Z. 1964, 16, 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, K.; Hasselblatt, B. The Sharkovsky Theorem: A Natural Direct Proof. Am. Math. Mon. 2011, 118, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, R. Simple mathematical models with very complicated dynamics. Nature 1976, 261, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, E.A. Perspectives of Nonlinear Dynamics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovich, S.; Berkolaiko, G.; Havlin, S. Solving nonlinear recursions. J. Math. Phys. 1996, 37, 5828–5836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, M.W.; Smale, S.; Devaney, R.L. Differential Equations, Dynamical Systems, and an Introduction to Chaos; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ruslan, A.T.; Marwan; Aini, Q. Behavior of logistic map and some of its conjugate maps. AIP Conf. Proc. 2022, 2641, 020002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layek, G.; Maps, C.O. An Introduction to Dynamical Systems and Chaos; University Texts in the Mathematical Sciences; Springer: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, A.; Ito, S. Computation of true chaotic orbits using cubic irrationals. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2014, 268, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persohn, K.J.; Povinelli, R.J. Analyzing logistic map pseudorandom number generators for periodicity induced by finite precision floating-point representation. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2012, 45, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galias, Z. Periodic orbits of the logistic map in single and double precision implementations. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2021, 68, 3471–3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöwer, M.; Coveney, P.V.; Paxton, E.A.; Palmer, T.N. Periodic orbits in chaotic systems simulated at low precision. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Song, D. The Property of Chaotic Orbits with Lower Positions of Numerical Solutions in the Logistic Map. Entropy 2014, 16, 5618–5632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, J.; Bruno, O.M. Dynamics and patterns of the least significant digits of the infinite-arithmetic precision logistic map orbits. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2024, 180, 114488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oteo, J.A.; Ros, J. Double precision errors in the logistic map: Statistical study and dynamical interpretation. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlinear Soft Matter Phys. 2007, 76, 036214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machicao, J.; Bruno, O.M. Improving the pseudo-randomness properties of chaotic maps using deep-zoom. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2017, 27, 053116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Pan, X. The reliable solution and computation time of variable parameters logistic model. Theor. Appl. Clim. 2018, 132, 851–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepomuceno, E.G.; Mendes, E.M. On the analysis of pseudo-orbits of continuous chaotic nonlinear systems simulated using discretization schemes in a digital computer. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2017, 95, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, M.L.; Nepomuceno, E.G.; Martins, S.A.; Lacerda, M.J. Computation of the largest positive Lyapunov exponent using rounding mode and recursive least square algorithm. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2018, 112, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akritas, P.; Antoniou, I.; Ivanov, V.V. Identification and prediction of discrete chaotic maps applying a Chebyshev neural network. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2000, 11, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrio, R.; Lozano, A.; Mayora-Cebollero, A.; Mayora-Cebollero, C.; Miguel, A.; Ortega, A.; Serrano, S.; Vigara, R. Deep Learning for chaos detection. Chaos 2023, 33, 073146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayora-Cebollero, C.; Fenton, F.H.; Halprin, M.; Herndon, C.; Toye, M.J.; Barrio, R. Deep learning for analyzing chaotic dynamics in biological time series: Insights from frog heart signals. Neurocomputing 2025, 660, 131820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayora-Cebollero, C.; Mayora-Cebollero, A.; Lozano, Á.; Barrio, R. Full Lyapunov exponents spectrum with Deep Learning from single-variable time series. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2025, 472, 134510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi, Y.; Kashavar, M.M.; Ghaffari, A.; Fotouhi, M.; Pedrammehr, S. CISMN: A Chaos-Integrated Synaptic-Memory Network with Multi-Compartment Chaotic Dynamics for Robust Nonlinear Regression. Mathematics 2025, 13, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, T.; Yang, H.; Zhang, J.; Small, M. Modeling chaotic systems: Dynamical equations vs machine learning approach. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2022, 114, 106452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanso, A.; Smaoui, N. Logistic chaotic maps for binary numbers generations. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2009, 40, 2557–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moysis, L.; Tutueva, A.; Volos, C.; Butusov, D.; Munoz-Pacheco, J.M.; Nistazakis, H. A Two-Parameter Modified Logistic Map and Its Application to Random Bit Generation. Symmetry 2020, 12, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Li, X.; Jin, B.; Li, Y. A Chaos-Based Encryption Algorithm to Protect the Security of Digital Artwork Images. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, A.; Frunzete, M. Image Encryption Using Chaotic Maps: Development, Application, and Analysis. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, D.D. Problems with chaotic cryptosystems. Cryptologia 1989, 13, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Mou, X.; Cai, Y.; Ji, Z.; Zhang, J. On the security of a chaotic encryption scheme: Problems with computerized chaos in finite computing precision. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2003, 153, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Liu, S.; Li, Z.; Lü, Z. A novel image encryption scheme based on spatial chaos map. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2008, 38, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihailescu, E. Inverse limits and statistical properties for chaotic implicitly defined economic models. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2012, 394, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, R.V.; Urban, R. Chaotic price behavior in a non-linear cobweb model. Econ. Lett. 1984, 15, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopel, M. Simple and complex adjustment dynamics in Cournot duopoly models. Chaos Solitons Fractals 1996, 7, 2031–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, R.H.; Huang, W. Bulls, bears and market sheep. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1990, 14, 299–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sordi, S.; Naimzada, A.; Davila-Fernandez, M.J. A dynamic model of real-financial markets interaction. Econ. Model. 2025, 149, 107103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, Y.; Nagashima, H. A note on a class of periodic orbits of the tent-map. Prog. Theor. Phys. 1989, 81, 541–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobson, M.V. Absolutely continuous invariant measures for one-parameter families of one-dimensional maps. Commun. Math. Phys. 1981, 81, 39–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisel, T.; Fairen, V. Statistical properties of chaos in Chebyshev maps. Phys. Lett. A 1984, 105, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Iteration | Digit Precision | Digit Precision | Computation Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0371380146975 | 0.037138014698137… | |

| 10 | 0.8951968882684 | 0.895196888266337… | |

| 100 | 0.9552148109433 | 0.955214810943948… | |

| 1000 | 0.4922984262885 | 0.492298426290442… | |

| 10,000 | 0.1316926680229 | 0.131692668022347… |

| Horizon of Predictability Equation (11) | Horizon of Predictability of | Horizon of Predictability of | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 1654 | 1659 | 1656 |

| 1000 | 3315 | 3322 | 3320 |

| 1500 | 4976 | 4980 | 4979 |

| 2000 | 6637 | 6642 | 6640 |

| 2500 | 8298 | 8302 | 8303 |

| 3000 | 9959 | 9965 | 9962 |

| 3500 | 11,620 | 11,624 | 11,622 |

| 4000 | 13,281 | 13,286 | 13,285 |

| 4500 | 14,942 | 14,947 | 14,950 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Angelidis, A.K.; Makris, G.C.; Ioannidis, E.; Antoniou, I.E.; Bratsas, C. How Far Can We Trust Chaos? Extending the Horizon of Predictability. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3851. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233851

Angelidis AK, Makris GC, Ioannidis E, Antoniou IE, Bratsas C. How Far Can We Trust Chaos? Extending the Horizon of Predictability. Mathematics. 2025; 13(23):3851. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233851

Chicago/Turabian StyleAngelidis, Alexandros K., Georgios C. Makris, Evangelos Ioannidis, Ioannis E. Antoniou, and Charalampos Bratsas. 2025. "How Far Can We Trust Chaos? Extending the Horizon of Predictability" Mathematics 13, no. 23: 3851. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233851

APA StyleAngelidis, A. K., Makris, G. C., Ioannidis, E., Antoniou, I. E., & Bratsas, C. (2025). How Far Can We Trust Chaos? Extending the Horizon of Predictability. Mathematics, 13(23), 3851. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233851