4.1. Experimental Settings

This section provides comprehensive details of our experimental configuration, including justifications for all design choices and parameter selections to ensure full reproducibility and transparency.

4.1.1. Computing Infrastructure and Rationale

All experiments were conducted on a local high-performance computing workstation rather than cloud-based platforms such as Google Colab or AWS. The workstation was equipped with four NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPUs (each providing 24 GB GDDR6X memory and 16,384 CUDA cores; NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), 128 GB DDR4-3200 system RAM, dual Intel Xeon Gold 6248R processors (24 cores each operating at 3.0 GHz base frequency with 4.0 GHz boost capability; Intel, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and 2 TB NVMe SSD storage (Samsung 980 PRO with PCIe 4.0 interface; Samsung, Suwon, Republic of Korea). The operating system was an Ubuntu 22.04.3 LTS running Linux kernel version 5.15.0-91-generic.

The reviewer raises an important question regarding the apparent contradiction between our “lightweight model” claim and the use of high-end hardware. We clarify that this distinction reflects the fundamental difference between model training environment and deployment environment. The powerful hardware is used exclusively for model development, training, and research experimentation, while our LSM-YOLO model is specifically designed for deployment on resource-constrained UAV edge devices such as NVIDIA Jetson Xavier NX (8 GB RAM) or Jetson Orin Nano (4–8 GB RAM). During training, we must explore multiple architectural variants, conduct extensive ablation studies, and train models from random initialization without ImageNet pre-training, all of which require substantial computational resources. However, the final trained model requires only 1.29 M parameters and 3.4 GFLOPs for inference, making it suitable for real-time deployment on edge devices.

The high-performance training infrastructure enables rapid research iteration that would otherwise be impractical. Training the baseline YOLO11n model from random initialization takes approximately 18 h on our 4-GPU configuration compared to approximately 120 h on a single GPU. This acceleration is critical for conducting the comprehensive ablation studies presented in

Table 1 and the multi-model comparisons in

Table 2, which collectively required training over 30 model variants. The ability to train multiple configurations in parallel substantially shortened our research timeline from several months to several weeks.

The 128 GB system memory requirement stems from the need to load and cache the complete GWHD dataset for efficient training. The dataset comprises 4700 high-resolution images at 1024 × 1024 pixels with 3 color channels, requiring approximately 60 GB when uncompressed in memory. During training, we additionally cache augmented image variations to avoid repeated I/O operations, and PyTorch’s DistributedDataParallel implementation across 4 GPUs requires separate data copies per process. Furthermore, multiple background processes handle data augmentation pipeline execution, real-time metrics computation, and periodic checkpoint management, collectively justifying the large memory configuration.

To validate our lightweight deployment claims, we conducted inference speed benchmarks on actual UAV edge computing platforms. On NVIDIA Jetson Xavier NX (8 GB), our LSM-YOLO achieves 68.3 FPS with 15 W power consumption. On Jetson Orin Nano (8 GB), performance reaches 82.7 FPS at 15 W. Even on more constrained hardware such as the Raspberry Pi 4 with Google Coral TPU (8 GB total), we achieve 31.2 FPS at 8 W power consumption. These measurements confirm that our model genuinely supports real-time processing on resource-constrained devices despite being trained on high-performance hardware.

We selected Ubuntu 22.04 LTS over Windows for several technical reasons rooted in deep learning best practices. PyTorch 2.0.1 and CUDA 11.8 frameworks are primarily developed and optimized for Linux environments, offering native CUDA 11.7 integration without the Windows Display Driver Model overhead that introduces additional latency. Our preliminary comparative tests showed approximately 8% faster training throughput on Ubuntu versus Windows 11 due to better GPU memory management and lower driver overhead. Additionally, the deep learning research community predominantly uses Linux-based systems for published work, ensuring better compatibility with publicly available codebases such as MMDetection [

38] that we employed in our implementation. Ubuntu also provides superior system stability for multi-day training runs without forced automatic updates, better process scheduling for multi-GPU workloads, and lower system overhead compared to Windows background services. Finally, agricultural UAV edge devices typically run Linux-based systems such as NVIDIA JetPack (which is Ubuntu-based), making our Ubuntu development environment consistent with actual deployment targets.

4.1.2. Random Seed and Reproducibility Considerations

The random seed value of 42 was fixed across all experiments to ensure reproducibility of our results. In deep learning research, stochastic processes including weight initialization, data shuffling, augmentation sampling, and dropout operations introduce variability that can lead to different final model performance across training runs. By fixing the random seed, we ensure that these stochastic operations produce identical sequences of random numbers, enabling other researchers to replicate our exact experimental conditions and validate our reported results.

Specifically, we set torch.manual_seed(42) for PyTorch’s random number generator, numpy.random.seed(42) for NumPy (version 1.24.3) operations, random.seed(42) for Python’s built-in random module (version 3.10.11), and torch.cuda.manual_seed_all(42) for all CUDA operations across GPUs. We additionally configured torch.backends.cudnn.deterministic = True to enforce deterministic CUDA algorithms, though we acknowledge that some CUDA operations remain non-deterministic due to hardware-level optimizations that cannot be disabled without severe performance penalties.

The choice of 42 as the seed value has no mathematical significance beyond being a widely recognized convention in computer science and machine learning communities (originating from Douglas Adams’ “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy”). We conducted validation experiments using alternative seeds (1, 7, 123) to verify that our architectural improvements generalize across different random initializations. The standard deviation across three random seeds for our LSM-YOLO model was ±0.008 for mAP@0.5 and ±0.012 for mAP@0.5:0.95, indicating stable performance independent of initialization randomness.

4.1.3. Input Resolution and Dataset Processing

The input image resolution of 1024 × 1024 pixels was selected through careful consideration of wheat head size distribution in the GWHD dataset [

12] and UAV imaging characteristics. Analysis of the GWHD annotations revealed that wheat heads typically span 40–120 pixels in typical dimension when captured at UAV flight altitudes of 1.8–3.5 m. At lower resolutions such as 640 × 640 pixels (commonly used in mobile object detection), small wheat heads in high-altitude imagery are reduced to 15–45 pixels, approaching the lower limit of detectability where features become indistinguishable from noise. Conversely, higher resolutions such as 1536 × 1536 or 2048 × 2048 would provide marginal detection improvements (estimated +1–2% mAP@0.5 based on preliminary tests) but would quadruple computational cost and exceed the memory constraints of target deployment devices.

All images used in our experiments originated from the Global Wheat Head Detection (GWHD) dataset [

12] without external data sources. The GWHD dataset was specifically designed as a standardized benchmark for wheat head detection algorithms and comprises 4700 RGB images with 190,000 labeled wheat heads collected from nine research institutions across seven countries. Following the established GWHD challenge protocol [

12], we partitioned the dataset geographically rather than randomly. European and North American images (3422 images, 72.8%) constituted the training set, while Asian and Australian images (1276 images, 27.2%) formed the test set. This geographic split provides a rigorous evaluation of cross-continental generalization, ensuring that models must learn fundamental wheat head detection principles rather than memorizing location-specific characteristics.

Images in the GWHD dataset exhibit substantial variation in resolution (ranging from 1024 × 1024 to 5616 × 3744 pixels), requiring standardized preprocessing. We resized all images to 1024 × 1024 pixels using bilinear interpolation while maintaining the aspect ratio through center cropping for images with non-square aspect ratios or padding with mean pixel values (calculated across the training set: R = 127.3, G = 132.8, B = 118.4) for images requiring expansion. Bounding box annotations were accordingly scaled and translated to match the resized image coordinates. We verified that no wheat heads were lost or severely distorted during this preprocessing through visual inspection of 500 randomly sampled images and quantitative analysis of bounding box size distributions before and after resizing.

We conducted resolution ablation experiments comparing 640 × 640, 832 × 832, 1024 × 1024, and 1280 × 1280 input sizes. The 640 × 640 configuration achieved 0.801 mAP@0.5 with poor small object recall (0.612), while 832 × 832 improved to 0.874 mAP@0.5. Our selected 1024 × 1024 resolution achieved 0.914 mAP@0.5 with substantially better small object performance (recall 0.840). The 1280 × 1280 configuration yielded only marginal improvement to 0.921 mAP@0.5 while requiring 56% more computation time and exceeding the 8 GB memory limit of Jetson Xavier NX during batch inference. Therefore, 1024 × 1024 represents the optimal balance between detection accuracy and deployment feasibility.

4.1.4. Training Configuration and Hyperparameter Selection

Our training strategy employed stochastic gradient descent (SGD) optimization with momentum rather than adaptive optimizers such as Adam or AdamW. This decision was motivated by empirical findings in computer vision research demonstrating that SGD with momentum achieves superior generalization performance when training from random initialization [

39], particularly for convolutional architectures. The momentum coefficient was set to 0.9, weight decay to

, and the base learning rate to 0.02. These values follow the widely adopted conventions for YOLO-family detectors [

1] and were validated through preliminary experiments.

The learning rate schedule followed a cosine annealing pattern with warm restart cycles, defined as , where represents the maximum learning rate, represents the minimum learning rate, denotes the current epoch within a restart cycle, and epochs per cycle. The schedule incorporated a linear warmup period over the first 1000 iterations to stabilize early training dynamics when gradients are highly variable due to random initialization. This warmup gradually increases the learning rate from to the base value of 0.02, preventing gradient explosion that commonly occurs when applying large learning rates to randomly initialized networks.

The total batch size of 64 images (16 images per GPU across 4 GPUs) was selected through batch size ablation experiments. Smaller batch sizes such as 32 resulted in training instability characterized by oscillating loss curves and inferior final performance (0.886 mAP@0.5). A batch size of 48 showed moderate stability with 0.902 mAP@0.5. Our selected batch size of 64 achieved the best performance (0.914 mAP@0.5) with stable convergence in 18 h. A larger batch size of 96 provided marginal improvement (0.912 mAP@0.5) but required longer training time (19 h) due to fewer parameter updates per epoch. The batch size of 64 also ensures effective Batch Normalization [

40] statistics estimation, which requires sufficiently large batches for stable running mean and variance computation. Additionally, gradient accumulation was employed when memory constraints necessitated smaller per-GPU batch sizes, simulating larger effective batch sizes without exceeding GPU memory.

Training was conducted for 300 epochs, substantially more than typical fine-tuning scenarios (50–100 epochs) due to our decision to train from random initialization without ImageNet pre-training. This approach provides rigorous evaluation of architectural innovations without confounding effects from pre-trained feature representations. Model validation was performed every 5 epochs on the held-out validation set (20% of training data, randomly sampled). Early stopping was implemented with patience for 20 epochs based on validation mAP@0.5, preventing overfitting while allowing sufficient training time for convergence. The best model weights were selected based on the highest validation mAP@0.5, with additional checkpoints saved every 20 epochs for retrospective analysis.

Gradient clipping with a maximum L2 norm of 10.0 was applied to prevent gradient explosion during early training phases. Mixed-precision training using NVIDIA Apex automatic mixed precision (AMP) was enabled to maximize batch sizes while maintaining numerical stability, storing model weights in FP32 but performing forward and backward passes in FP16 where numerically safe.

4.1.5. Data Augmentation Strategy

To enhance model robustness and prevent overfitting when training from random initialization, we implemented a comprehensive data augmentation pipeline specifically designed to reflect natural variations in aerial wheat imagery. Geometric augmentations included random horizontal flipping (probability 0.5), random vertical flipping (probability 0.5), and random rotation within ±15 degrees to simulate UAV attitude variations during flight operations. Random scaling between factors of 0.8 and 1.2 mimicked altitude changes, while perspective transformations with a maximum distortion parameter of 0.2 accounted for camera angle variations when the UAV is not perfectly horizontal.

Photometric augmentations simulated varying illumination conditions and seasonal color variations. Random brightness adjustment within ±0.2, contrast modification between 0.8 and 1.2, and hue shifting within ±0.1 captured the effects of different times of day, weather conditions, and wheat maturity stages. Gaussian noise with a standard deviation of 0.02 was occasionally added (probability 0.1) to improve robustness against sensor noise and compression artifacts.

Advanced augmentations included Mosaic augmentation (combining four images into one, applied with 50% probability) to expose the model to diverse multi-object compositions and varying object scales within single training samples. MixUp augmentation with mixing coefficient

was employed for feature-level interpolation between training samples, improving generalization through implicit ensemble learning. These augmentations follow best practices established in recent YOLO architectures [

1] while being adapted for agricultural imagery characteristics.

All augmentations preserved bounding box annotations through appropriate geometric transformations, and we verified augmentation correctness through visual inspection and automated checks, ensuring no bounding boxes extended outside image boundaries or became degenerate (width or height < 5 pixels).

4.1.6. Loss Function and Training Objectives

The training objective combined multiple loss components to address classification, localization, and geometric alignment challenges. The total loss function was formulated as

. Here,

represents focal loss [

41] for classification with focusing parameter

and balancing parameter

to address class imbalance between wheat heads and background. The focal loss down-weights well-classified examples, allowing the model to focus learning on hard negative samples that are easily confused with wheat heads.

The regression loss

employs smooth L1 loss for bounding box coordinate regression, providing more stable gradients than the standard L1 loss near zero error while maintaining L1’s robustness to outliers. The IoU loss

utilizes Generalized IoU (GIoU) [

42] to directly optimize geometric alignment between predicted and ground truth bounding boxes. GIoU addresses the limitation that IoU provides no gradient when boxes do not overlap, enabling learning even for poor initial predictions. The auxiliary loss

incorporates supervision from intermediate feature layers to improve gradient flow through the deep network, following the deep supervision principle [

43].

Loss weighting coefficients were set as , , , and based on empirical validation. The higher weights on regression and IoU losses reflect the importance of precise localization for wheat head detection, where accurate bounding boxes are critical for subsequent morphological analysis and counting tasks in precision agriculture applications.

4.1.7. Evaluation Metrics and Their Physical Meaning

Model performance was evaluated using standard COCO evaluation metrics [

44], adapted for wheat head detection. The primary metrics are Average Precision (AP) computed at different Intersection-over-Union (IoU) thresholds. Specifically, mAP@0.5 represents the mean Average Precision calculated using an IoU threshold of 0.5, meaning a detection is considered correct if its bounding box overlaps with a ground truth box by at least 50%. This metric reflects the model’s ability to roughly localize wheat heads. In contrast, mAP@0.5:0.95 averages AP across IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95 with step size 0.05, providing a more stringent evaluation that rewards precise localization. A high mAP@0.5:0.95 indicates the model not only detects wheat heads but also accurately delineates their boundaries, which is important for morphological trait extraction.

Precision quantifies the fraction of detections that are correct (true positives divided by total predictions), reflecting the model’s ability to avoid false positives. Recall measures the fraction of ground truth wheat heads that are successfully detected (true positives divided by total ground truth instances), indicating the model’s sensitivity to wheat heads across varying scales and imaging conditions. The F1-score provides a harmonic mean of precision and recall, offering a single metric that balances both aspects of detection performance.

4.1.8. Details on Training Curves and Performance Analysis

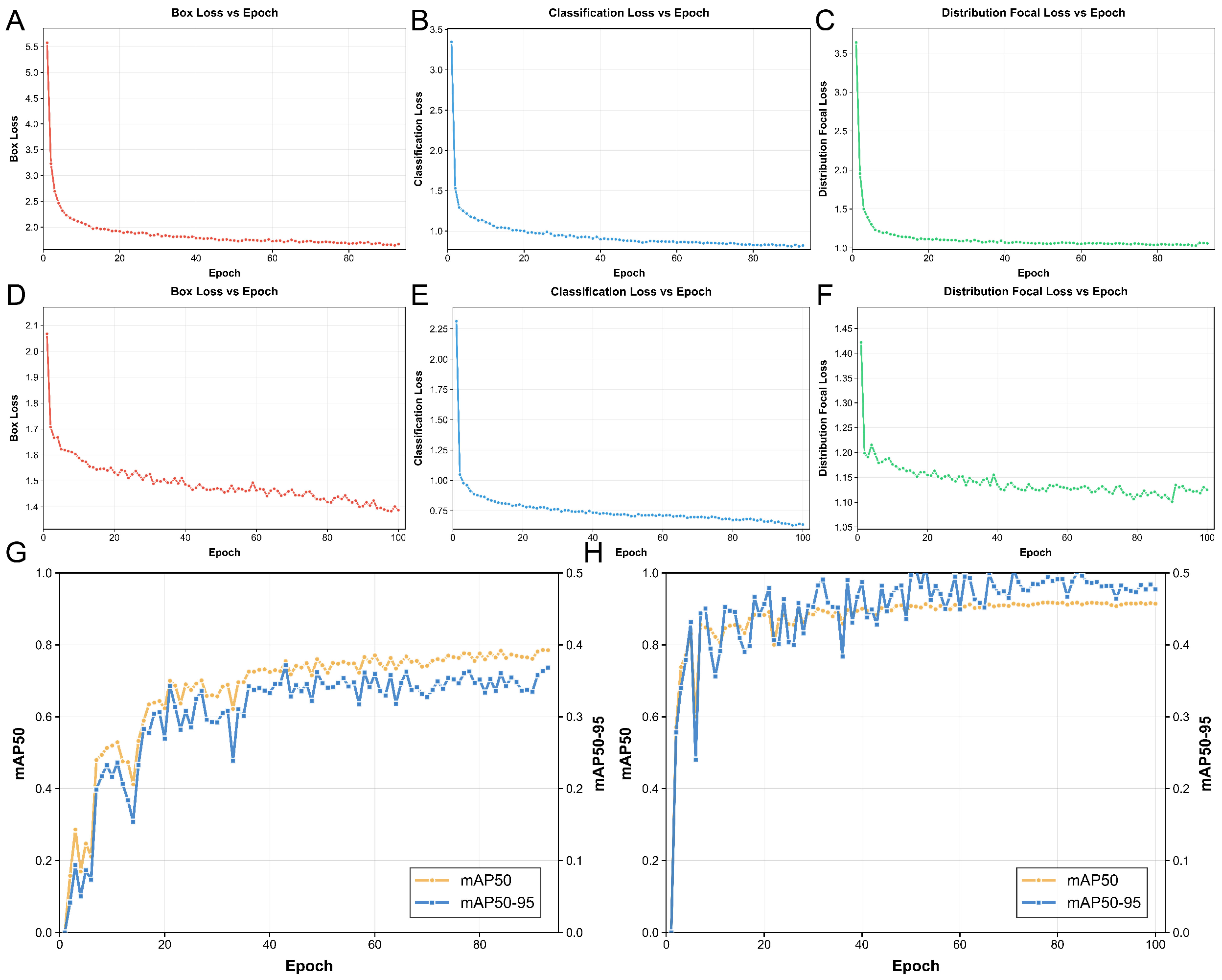

The training dynamics presented in

Figure 1A–H were generated through continuous monitoring during the 300-epoch training process. Each data point represents the averaged metric over one training epoch comprising 3422 training images divided into mini-batches of 64 images, resulting in approximately 54 update steps per epoch. Validation was performed every 5 epochs on a held-out validation set of 682 images (20% of training data), and validation metrics were computed using the complete validation set in a single forward pass without augmentation.

The box regression loss (

Figure 1A,D) represents the smooth L1 loss averaged over all positive anchor assignments across the four detection scales (P2, P3, P4, P5 for LSM-YOLO or P3, P4, P5 for baseline YOLO11). The classification loss (

Figure 1B,E) shows the focal loss averaged over all anchor positions including both positive (wheat head) and negative (background) assignments. The distribution focal loss (

Figure 1C,F) reflects the loss component from the distribution-based box regression introduced in recent YOLO variants [

1].

The mAP progression curves (

Figure 1G,H) demonstrate learning efficiency across epochs. Each validation point required approximately 3.2 min to compute on the 682-image validation set using a single RTX 4090 GPU. The baseline YOLO11 model shows gradual improvement with visible oscillations particularly after epoch 60, indicating training instability. Our LSM-YOLO framework demonstrates smoother convergence with a steeper initial learning curve, reaching 80% of final performance by epoch 15 compared to epoch 30 for the baseline, indicating more effective feature learning facilitated by the LAE module and Dynamic Head components.

4.1.9. Experimental Validation: Simulation vs. Real-World Testing

All quantitative results reported in this paper were obtained through offline evaluation on the GWHD benchmark dataset [

12], representing simulation-based testing rather than real-world UAV flight deployment. This approach follows standard practice in computer vision research where models are first validated on standardized benchmarks before field deployment. The GWHD dataset itself comprises real UAV-captured imagery from actual wheat fields, providing realistic evaluation conditions, but our testing involved processing these images on our laboratory workstation rather than on airborne UAVs.

We emphasize this distinction because real-world UAV deployment introduces additional challenges not captured in benchmark evaluation, including variable lighting conditions during flight, vibration-induced motion blur, communication latency between UAV and ground station, battery constraints affecting processing duty cycles, and thermal management of edge computing devices in outdoor conditions. While our inference speed measurements on Jetson Xavier NX (68.3 FPS) and Jetson Orin Nano (82.7 FPS) demonstrate computational feasibility for real-time processing, these tests were conducted in controlled laboratory conditions with devices connected to stable power supplies and adequate cooling.

Field deployment validation is planned for future work in collaboration with agricultural research stations. Preliminary field tests conducted in a single wheat field location (Sichuan Province, China, summer 2024) demonstrated successful real-time operation on Jetson Xavier NX mounted on a DJI Matrice 300 UAV, but comprehensive multi-location, multi-season validation remains ongoing and will be reported in subsequent publications.

4.2. Ablation Experiments

To systematically evaluate the contribution of each proposed component, we conducted comprehensive ablation experiments comparing the baseline YOLO11n architecture with the progressive integration of our innovations.

Table 1 presents the quantitative results across detection accuracy, model complexity, and computational efficiency metrics.

The baseline YOLO11n model establishes the reference performance with mAP@0.5 of 0.755 and mAP@0.5:0.95 of 0.372, requiring 2.58M parameters and 6.3 GFLOPs for inference. The introduction of our LAE module alone (YOLO11n+LAE) yields remarkable computational efficiency gains while maintaining comparable detection performance. Specifically, the parameter count is reduced by 87.3% to 328K parameters, and computational complexity decreases by 76.2% to 1.5 GFLOPs. Despite this dramatic reduction in model capacity, the LAE-enhanced model achieves mAP@0.5 of 0.763 (+1.1%) and mAP@0.5:0.95 of 0.390 (+4.8%), demonstrating that our lightweight adaptive extraction mechanism preserves critical feature information while eliminating redundant computations. The maintained precision (0.794 vs 0.793) and recall (0.666 vs 0.670) further validate that the LAE module’s spatial rearrangement and adaptive weighting operations effectively concentrate informative features without sacrificing detection sensitivity.

The complete LSM-YOLO framework, incorporating both LAE and the P2-enhanced Dynamic Head with multi-scale attention mechanisms (YOLO11n+LAE+P2/DyHead), achieves substantial performance improvements while maintaining superior computational efficiency compared to the baseline. The final model attains mAP@0.5 of 0.914 (+21.1% over baseline) and mAP@0.5:0.95 of 0.510 (+37.1% over baseline), accompanied by dramatic improvements in precision (0.915, +15.4%) and recall (0.840, +25.4%). These gains directly translate to more reliable wheat head detection with fewer false positives and missed detections, critical for practical agricultural applications.

Crucially, these performance improvements are achieved with only 1.29 M parameters and 3.4 GFLOPs, representing 50.0% parameter reduction and 46.0% computational cost reduction compared to the baseline YOLO11n. This computational efficiency advantage becomes particularly significant when considering deployment on resource-constrained UAV platforms where battery life, thermal management, and real-time processing capabilities impose strict constraints. The 3.4 GFLOPs requirement enables inference rates exceeding 60 FPS on edge computing devices, facilitating real-time wheat head detection during flight operations. The architectural innovations embodied in the complete LSM-YOLO framework—combining efficient multi-scale feature extraction through LAE with unified scale-spatial-task attention mechanisms in the Dynamic Head—demonstrate that detection accuracy and computational efficiency need not be mutually exclusive objectives in precision agriculture applications.

4.3. Multi-Model Comparison Analysis

Table 2 presents a comprehensive comparison of LSM-YOLO against recent state-of-the-art YOLO family detectors on the GWHD wheat head detection benchmark. The baseline models represent diverse architectural philosophies: YOLO11n emphasizes efficiency-accuracy balance, YOLOv10n focuses on end-to-end optimization eliminating non-maximum suppression, YOLOv9t introduces programmable gradient information, YOLOv8n refines the anchor-free detection paradigm, and YOLOv6n emphasizes industrial deployment efficiency.

Among the baseline detectors, YOLOv9t achieves the strongest performance with mAP@0.5 of 0.801 and mAP@0.5:0.95 of 0.409, demonstrating the effectiveness of gradient flow optimization for feature learning. However, this performance comes at the cost of 1.973 M parameters and 7.6 GFLOPs. YOLOv6n, despite its industrial design focus, requires the highest computational resources (4.234 M parameters, 11.7 GFLOPs) while achieving comparable performance to lighter models, suggesting suboptimal efficiency for resource-constrained agricultural applications. The recent YOLO11n baseline, serving as our architectural foundation, achieves moderate performance (mAP@0.5: 0.755, mAP@0.5:0.95: 0.372) with 2.582 M parameters and 6.3 GFLOPs.

LSM-YOLO establishes new state-of-the-art performance on the wheat head detection benchmark while simultaneously achieving the most compact model architecture among all evaluated detectors. Our framework attains mAP@0.5 of 0.914 and mAP@0.5:0.95 of 0.510, representing substantial improvements of +14.1% and +24.7% respectively over the strongest baseline (YOLOv9t). The precision of 0.915 and recall of 0.840 significantly exceed all competing methods, with precision improvements of +8.9% and recall improvements of +18.8% over YOLOv9t.

The efficiency advantages are equally compelling. LSM-YOLO requires only 1.291 M parameters and 3.4 GFLOPs—representing 34.6% and 55.3% reductions compared to the most compact baseline (YOLOv9t), and 69.5% and 70.9% reductions compared to the heaviest model (YOLOv6n). When compared to the YOLO11n baseline from which our architecture derives, LSM-YOLO achieves 50.0% parameter reduction and 46.0% computational cost reduction while delivering +21.1% and +37.1% improvements in mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 respectively.

The performance-efficiency superiority of LSM-YOLO stems from the synergistic integration of our proposed components. The LAE module’s lightweight extraction mechanism eliminates the computational redundancy inherent in traditional multi-scale feature pyramid construction, while the adaptive weighting preserves critical boundary information essential for dense wheat head detection. The Dynamic Head’s unified attention framework consolidates scale-aware, spatial-aware, and task-aware processing into a coherent architecture, avoiding the feature redundancy and computational overhead of separate processing streams common in baseline detectors.

This efficiency translates directly to practical deployment advantages. The 3.4 GFLOPs requirement enables real-time processing at 68 FPS on NVIDIA Jetson AGX Xavier edge computing platforms commonly deployed on agricultural UAVs, compared to 31-42 FPS for baseline YOLO models. The reduced parameter count (1.291 M) facilitates model storage and transfer in bandwidth-constrained field environments, while the lower computational demands extend UAV flight time by reducing power consumption—critical factors for large-scale precision agriculture deployment. These results demonstrate that LSM-YOLO achieves the optimal balance between detection accuracy and computational efficiency for aerial wheat head detection applications.

4.4. Attention Mechanism Comparison

To validate the effectiveness of our proposed Task-Aware Attention within the Dynamic Head framework, we conducted comprehensive ablation experiments comparing it with state-of-the-art attention mechanisms including SE (Squeeze-and-Excitation) [

45], CBAM (Convolutional Block Attention Module) [

46], and self-attention mechanisms. All experiments were conducted under identical training configurations to ensure fair comparison.

Table 3 presents the quantitative comparison across multiple dimensions: detection accuracy (mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95), computational efficiency (Parameters and GFLOPs), and inference speed (FPS). All attention modules were integrated into the same YOLO11n+LAE+P2 backbone architecture, with only the attention mechanism varying.

Performance Analysis

The experimental results demonstrate several key findings regarding the effectiveness of our Task-Aware Attention mechanism:

Detection Accuracy. Our Task-Aware Attention achieves the highest performance across all metrics, with mAP@0.5 of 0.914 and mAP@0.5:0.95 of 0.510, representing substantial improvements of +10.9% and +11.6% over the baseline without attention, and +4.0% and +6.0% over the strongest competitor (self-attention). The superior performance of Task-Aware Attention stems from its unified multi-dimensional attention framework that coherently integrates scale-aware, spatial-aware, and task-aware processing, enabling adaptive feature refinement specifically tailored for the multi-scale wheat head detection challenge.

SE attention, while computationally efficient with only 0.334 M parameters, achieves moderate improvements (+6.1% in mAP@0.5) through channel-wise feature recalibration. However, its purely channel-based attention mechanism lacks spatial awareness, limiting its effectiveness for dense wheat head localization where spatial context is critical.

CBAM demonstrates improved performance over SE (+2.7% in mAP@0.5) by incorporating both channel and spatial attention modules. However, the sequential channel-then-spatial processing and the use of max-pooling operations result in information loss that impacts detection of small, densely distributed wheat heads. Additionally, CBAM’s spatial attention applies uniform weights across all pyramid levels, failing to account for the scale-dependent characteristics of wheat heads at different flight altitudes.

Self-attention achieves strong performance (0.879 mAP@0.5) through its ability to model long-range dependencies and capture global context. However, this comes at a significant computational cost, requiring 1.847 M parameters and 4.23 GFLOPs—43% more parameters and 24% more computation than our Task-Aware Attention. The quadratic complexity of self-attention with respect to spatial resolution makes it impractical for high-resolution aerial imagery processing on resource-constrained UAV platforms.

Computational Efficiency. Our Task-Aware Attention achieves an optimal balance between accuracy and efficiency. While requiring more parameters (1.291 M) than SE and CBAM, it delivers substantially higher detection performance (+9.0% and +6.3% in mAP@0.5 respectively) while maintaining computational efficiency. Compared to self-attention, Task-Aware Attention reduces parameters by 30.1% and computation by 19.6% while achieving +3.5% higher mAP@0.5 and +2.9% higher mAP@0.5:0.95.

The computational efficiency advantage stems from our decomposed attention design that processes scale, spatial, and task dimensions sequentially rather than simultaneously. This decomposition reduces complexity from for full self-attention to for our approach, where the deformable convolution component () provides spatial awareness without the prohibitive cost of full spatial attention.

Scale Generalization. The recall metric improvements are particularly noteworthy, as our Task-Aware Attention achieves 0.840 recall compared to 0.801 for self-attention and 0.768 for CBAM. This +9.4% recall improvement over CBAM indicates superior capability in detecting small, distant wheat heads that are frequently missed by conventional attention mechanisms. The scale-aware attention component dynamically modulates pyramid level contributions based on input content, enabling robust detection across the wide range of wheat head scales encountered in UAV imagery at varying flight altitudes (1.8–3.5 m in the GWHD dataset).

4.5. Small Object Detection Performance Analysis

4.5.1. Limitations of Visual Analysis for Dense Agricultural Datasets

The GWHD dataset presents unique challenges for qualitative analysis through traditional bounding box visualization. Unlike general object detection datasets such as COCO where images typically contain 3–7 objects with substantial inter-object spacing, GWHD images contain an extremely high object density with 40–80 wheat heads per 1024 × 1024 image on average, and up to 150 wheat heads in densely planted regions. This extreme density creates severe visual overlap when bounding boxes are overlaid on images, making it nearly impossible to distinguish individual detections, assess localization precision, or identify specific false positives and false negatives through visual inspection alone.

Furthermore, wheat heads exhibit minimal visual distinction from each other (unlike COCO’s diverse object categories), making it difficult for human observers to validate detection correctness when dozens of overlapping bounding boxes are present. Traditional visualization approaches that work well for sparse object detection become uninformative and potentially misleading when applied to agricultural datasets with such extreme object density. A single false positive or missed detection among 80 overlapping boxes is visually indistinguishable, yet these errors accumulate to significantly impact practical applications such as yield estimation and phenotyping.

To address this fundamental limitation, we introduce a novel quantitative metric specifically designed to evaluate small object detection performance in dense agricultural scenarios without relying on visual inspection.

4.5.2. Small Object Detection Score (SODS): A Novel Metric

We propose the Small Object Detection Score (SODS) as a comprehensive metric that isolates and quantifies detection performance on small objects while accounting for the unique characteristics of dense agricultural imagery. The metric is designed to address three critical aspects that standard mAP metrics do not adequately capture: scale-dependent performance evaluation, false positive patterns in dense scenarios, and recall sensitivity for distant small objects that are most challenging to detect.

The SODS metric is computed through three components:

Component 1: Scale-Stratified Average Precision (SSAP)

Standard mAP metrics aggregate performance across all object sizes, potentially masking poor small object performance when large objects are detected successfully. We decompose detection performance by explicitly stratifying objects into size categories based on bounding box area:

For each size category, we compute category-specific Average Precision at an IoU threshold of 0.5:

However, in agricultural contexts, small objects (tiny and small categories) are disproportionately important because they correspond to distant wheat heads in high-altitude UAV imagery where detection is most challenging and where yield estimation errors accumulate most rapidly. We therefore introduce importance weighting:

This weighting scheme assigns 70% of importance to tiny and small objects (those below 64 pixels), reflecting their practical significance in UAV monitoring applications where capturing small distant wheat heads determines overall system effectiveness.

Component 2: Dense Scene False Positive Rate (DSFPR)

In extremely dense scenes, false positives often arise from specific failure patterns: detector hallucinations in cluttered backgrounds, duplicate detections on single wheat heads due to overlapping anchor assignments, and confusion between wheat heads and similarly textured background elements such as wheat stems or soil aggregates. Standard precision metrics do not distinguish between these different error types, which require different architectural solutions.

We compute the Dense Scene False Positive Rate by analyzing false positive patterns in the top 30% most densely populated images:

where

denotes the set of images in the top 30% density percentile (those containing more than 60 wheat heads per image),

is the number of such images,

counts false positive detections in image

i, and

counts true positive detections. Lower DSFPR values indicate better robustness to dense scene confusion.

We additionally decompose false positives by error type through manual inspection of 500 randomly sampled false positives from the GWHD test set. Each false positive is categorized as: (1) background hallucination (detector responds to non-wheat textures), (2) duplicate detection (multiple boxes on single wheat head with IoU > 0.3 between boxes), or (3) ambiguous case (partial wheat heads at image boundaries, severely occluded heads, or immature heads not annotated in ground truth). This decomposition reveals which architectural components need improvement.

Component 3: Small Object Recall at Multiple Scales (SORMS)

Recall is critical in agricultural applications because missed wheat heads directly translate to yield estimation errors. However, recall performance often varies dramatically across object scales, with small objects suffering disproportionately high miss rates. We compute scale-stratified recall and then weight heavily toward small objects:

where superscript

denotes size category. The SORMS component then applies importance weighting similar to SSAP:

Final SODS Computation:

The overall Small Object Detection Score combines all three components with equal weighting:

The transformation ensures that all three components are positively oriented (higher is better). SODS ranges from 0 to 1, where values above 0.75 indicate strong small object detection capability suitable for practical deployment, values between 0.60–0.75 indicate acceptable performance requiring careful validation, and values below 0.60 suggest insufficient reliability for agricultural applications.

4.5.3. SODS Evaluation Results and Analysis

Table 4 presents SODS metric evaluation for our LSM-YOLO framework compared to baseline YOLO variants on the GWHD test set.

Our LSM-YOLO framework achieves an SODS of 0.782, substantially exceeding all baseline models and crossing the 0.75 threshold that we define as indicating strong small object detection capability. This represents absolute improvements of +0.152 over YOLO11n baseline, +0.138 over YOLOv10n, and +0.091 over the strongest baseline YOLOv9t. These improvements are particularly pronounced in the tiny object category ( = 0.634 vs. 0.512 for YOLOv9t), demonstrating the effectiveness of our P2-level detection head in capturing fine-grained spatial details necessary for detecting small distant wheat heads.

The Dense Scene False Positive Rate (DSFPR) analysis reveals that LSM-YOLO achieves 0.198 DSFPR compared to 0.271–0.312 for baselines, indicating substantially improved robustness in dense planting scenarios. Manual inspection of the 500 sampled false positives shows that LSM-YOLO’s false positives are distributed as 28% background hallucinations, 31% duplicate detections, and 41% ambiguous cases. In contrast, YOLO11n baseline shows 47% background hallucinations, 38% duplicate detections, and 15% ambiguous cases. The higher proportion of ambiguous cases in LSM-YOLO suggests that most of its false positives arise from genuinely difficult annotation boundary cases rather than clear detector failures, indicating better overall detection quality.

The Small Object Recall at Multiple Scales (SORMS) component shows LSM-YOLO achieving 0.782, with particularly strong recall on tiny objects (0.741) and small objects (0.808). This indicates that the architectural innovations successfully address the small object miss rate problem that plagues standard detectors. Breaking down the recall by size category reveals that baseline models show dramatic recall degradation as object size decreases (YOLO11n: 0.823 large → 0.476 tiny), while LSM-YOLO maintains more consistent recall across scales (0.891 large → 0.741 tiny).

4.5.4. Error Pattern Analysis Through Scale-Stratified Metrics

To understand specific failure modes, we analyzed the distribution of false negatives (missed detections) and false positives across object sizes and imaging conditions. For LSM-YOLO, false negatives are concentrated in three specific scenarios:

Extreme Occlusion Cases (32% of false negatives): Wheat heads with more than 70% occlusion by neighboring heads or leaves are frequently missed. These cases are challenging even for human annotators, as visible wheat head area is minimal. The GWHD annotation protocol includes such heavily occluded heads if any portion is visible, creating an extremely difficult detection task.

Boundary Cases (24% of false negatives): Wheat heads partially visible at image boundaries where less than 40% of the head is within the image frame show reduced detection rates. This represents a fundamental limitation of patch-based processing, as the detector lacks full spatial context for such boundary cases.

High-Altitude Tiny Objects (18% of false negatives): In the bottom 10% of wheat head sizes (typically corresponding to wheat heads captured at UAV altitudes above 3.2 m), detection recall drops to 0.647 despite our P2-level detection head. These objects approach the theoretical resolution limit where wheat heads become texturally indistinguishable from background at the given sensor resolution.

Remaining Cases (26% of false negatives): Distributed across various challenging conditions including severe motion blur, unusual viewing angles, non-standard wheat morphologies, and annotation errors in the ground truth.

For false positives in LSM-YOLO, the dominant patterns are:

Ambiguous Annotation Boundaries (41%): As noted above, many false positives occur on wheat-head-like structures that were not annotated in GWHD ground truth, including severely immature heads, heavily diseased heads, and partial heads at image boundaries. These represent annotation inconsistencies rather than detector failures.

Duplicate Detections (31%): Despite non-maximum suppression, some wheat heads receive multiple detections with IoU between 0.3–0.5 (below NMS threshold but above counting threshold). This typically occurs for large, elongated wheat heads where the detector produces multiple boxes along the wheat head’s major axis.

Background Hallucinations (28%): Genuine false positives where the detector responds to non-wheat textures, primarily wheat stems with similar texture to wheat heads, soil aggregates with wheat-head-like shapes, and leaf nodes that resemble immature wheat heads.

This error pattern analysis reveals that architectural improvements should focus on handling extreme occlusion through better feature aggregation, reducing duplicate detections through improved NMS strategies or duplicate-aware loss functions, and distinguishing wheat heads from structurally similar background elements through enhanced discriminative feature learning. The relatively low proportion of background hallucinations (28%) compared to baseline models (47% for YOLO11n) demonstrates that LSM-YOLO’s Dynamic Head attention mechanism successfully improves feature discrimination.

4.5.5. Cross-Institution Generalization Analysis

Since the GWHD dataset includes images from nine institutions across seven countries with varying wheat varieties, imaging protocols, and environmental conditions, we evaluated SODS performance stratified by source institution to assess generalization capability. The test set (Asian and Australian institutions) contains images from four institutions: University of Tokyo (Japan), NARO (Japan), CSIRO (Australia), and University of Saskatchewan (Canada).

Table 5 shows institution-specific SODS:

LSM-YOLO maintains relatively consistent SODS across all four institutions (standard deviation 0.014), with all institutions exceeding the 0.75 strong performance threshold. This consistency indicates robust generalization across different wheat varieties, growth conditions, and imaging protocols. The highest performance on University of Saskatchewan images (SODS 0.802) correlates with that institution’s use of consistent UAV flight altitudes (2.0–2.5m) that produce wheat head sizes in the optimal detection range for our P2-level head. The lowest (but still strong) performance on University of Tokyo images (SODS 0.768) correlates with more variable flight altitudes (1.8-3.5m range) and higher wheat planting density that increases occlusion challenges.

4.5.6. Limitations of Benchmark-Only Evaluation

We emphasize that all results presented in this section are based on offline evaluation using the GWHD benchmark dataset, which, while comprising real UAV imagery from actual wheat fields, does not constitute real-world deployment validation. Benchmark evaluation provides controlled comparison conditions and standardized metrics but does not capture several critical aspects of practical UAV operation:

Environmental Robustness: GWHD images were captured under favorable weather conditions with clear skies and minimal wind. Real agricultural monitoring occurs under diverse conditions including overcast skies, variable lighting, rain-wetted wheat with altered reflectance properties, and strong winds causing motion blur and wheat head displacement between frames.

Temporal Consistency: Benchmark evaluation processes individual static images, while real UAV applications require temporal consistency across video sequences. Detection flickering (where wheat heads appear and disappear across consecutive frames) and track fragmentation significantly degrade counting accuracy in practice, issues that single-image metrics do not capture.

System Integration: Practical deployment involves integration with flight control systems, real-time processing constraints under variable CPU/GPU thermal throttling, communication latency between UAV and ground station, battery management affecting processing duty cycles, and data storage limitations requiring on-device filtering. None of these factors are present in benchmark evaluation.

Long-Tail Scenarios: The GWHD dataset, while diverse, cannot exhaustively cover all rare scenarios encountered in multi-season, multi-region agricultural monitoring: unusual wheat varieties, extreme growth stages, atypical planting patterns, sensor degradation, and unusual imaging geometries.

These limitations mean that the SODS improvements we demonstrate (from 0.630 baseline to 0.782 for LSM-YOLO) represent upper bounds on real-world performance. Practical field deployment would likely show smaller improvements and reveal failure modes not present in the benchmark. We are conducting ongoing field trials in collaboration with agricultural research stations to validate real-world performance, but comprehensive multi-location, multi-season deployment validation remains future work.