1. Introduction

The widespread application of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) in fields such as agricultural monitoring, post-disaster rescue, and infrastructure inspection has established them as a major research focus in the domain of intelligent equipment. Autonomous navigation capability, being a core performance metric, directly determines the accuracy and reliability of mission execution [

1]. In complex scenarios such as indoors or urban canyons, UAVs face challenges including GPS signal denial, drastic illumination changes, and interference from dynamic obstacles, necessitating reliance on onboard sensors for autonomous localization. Under these conditions, the accuracy and robustness of pose estimation become the critical factor determining the upper limit of navigation performance [

2].

To overcome the limitations of single-sensor approaches, Visual–Inertial Odometry (VIO) technology, which combines high-precision spatial information from cameras with high-frequency motion data from IMUs, has emerged as a mainstream solution [

3,

4,

5]. Early VIO methods primarily relied on filtering or optimization techniques. In 2015, Leutenegger et al. proposed OKVIS [

6], a keyframe-based optimization method that achieves high-precision pose estimation by jointly optimizing visual feature points and IMU measurements. While this method excels in static environments, its robustness in feature extraction and matching proves insufficient in dynamic scenes or under visual degradation, leading to a decline in pose estimation accuracy. Subsequently, Forster et al. [

7] introduced SVO+MSF in 2017, which combines semi-direct visual odometry with an Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) for IMU data fusion, significantly improving computational efficiency. However, such methods depend heavily on hand-crafted feature extractors and prior motion models. When confronted with visually challenging scenarios such as severe motion blur, weak textures, or sudden illumination changes, the stability of their feature extraction and matching processes deteriorates sharply, often resulting in reduced localization accuracy or even tracking failure. This inherent limitation constitutes a fundamental obstacle to their application in complex, dynamic environments.

To break through the bottlenecks of traditional methods, deep learning-based end-to-end VIO approaches have emerged [

8,

9,

10]. In 2017, Clark et al. [

11] proposed VINet, framing Visual–Inertial Odometry as a sequence-to-sequence regression task for the first time. It employed an end-to-end framework combining CNNs and LSTMs to directly output 7-DoF poses from monocular RGB images and six-axis IMU data, demonstrating the feasibility of the end-to-end paradigm. Subsequent works like DeepVIO [

12] further improved accuracy by introducing deeper network architectures and more complex loss functions. Despite significant progress, these works mostly employ a static or implicit fusion mechanism. Specifically, these methods typically extract deep features in separate encoders before performing simple concatenation or weighted fusion via attention mechanisms at the top level of the network. Consequently, when the overall data quality of one modality degrades, the network cannot effectively suppress the contribution of the noisy modality, which severely compromises the model’s robustness and final accuracy in complex dynamic scenes. Furthermore, to extract effective features from high-dimensional visual data, existing works often rely on large-scale CNN backbone networks. Although this has enhanced performance, it has also introduced a significant computational burden, making it difficult to apply them effectively on resource-constrained edge devices.

To address the aforementioned issues of inadequate fusion mechanisms and high model complexity, this paper proposes a Two-stage Sequential Fusion Network (TSFNet). It aims to achieve more efficient visual–inertial collaboration while significantly reducing the computational burden through a carefully designed lightweight architecture.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

A novel two-stage fusion architecture TSFNet is proposed, which decouples adaptive intra-frame multi-modal feature fusion from explicit inter-frame motion temporal modeling, providing a more robust and efficient implementation paradigm for end-to-end VIO.

We design an adaptively weighted hybrid loss function that effectively balances the optimization of translation and rotation tasks, enhancing the model’s robustness in complex scenarios.

Extensive experiments on public EuRoC and Zurich Urban MAV datasets demonstrate that the proposed TSFNet outperforms baseline models, validating the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed method.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the related work.

Section 3 introduces the proposed method.

Section 4 presents the experimental results and analysis.

Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

This section reviews related work in visual–inertial navigation, primarily covering three aspects: single-modality sensor navigation, traditional visual–inertial fusion methods, and data-driven deep learning approaches.

2.1. Single-Modality Sensor Navigation Methods

Single-sensor methods laid the foundation for pose estimation, enabling independent navigation using either visual or inertial data. Vision-based odometry algorithms [

13,

14] reconstruct 3D structure via feature point matching or direct methods, performing well in texture-rich environments. However, they are highly sensitive to illumination changes and rapid motion, often leading to trajectory drift or tracking failure [

15]. In contrast, Inertial Navigation Systems (INSs) based on IMUs utilize high-frequency measurements from accelerometers and gyroscopes to compute position and attitude through integration, offering rapid dynamic response. Nevertheless, they suffer from accumulating errors, causing a sharp decline in accuracy over extended operation [

16]. Although these single-modality methods can meet requirements in specific scenarios, their inherent limitations make them unsuitable for complex dynamic environments. In particular, when sensor data is affected by noise, occlusions, or other disturbances, system robustness significantly degrades [

17]. Consequently, designing a mechanism capable of dynamically balancing and deeply integrating these two complementary modalities—vision and inertial data—to overcome the limitations of single-sensor approaches constitutes a critical challenge that must be addressed to enhance the robustness of pose estimation systems.

2.2. Filter-Based and Optimization-Based Visual–Inertial Navigation Methods

Traditional Visual–Inertial Navigation Systems (VINSs) methods overcome the limitations of single-sensor approaches by fusing high-precision spatial information from cameras with high-frequency motion data from IMUs. The development of these methods can be broadly categorized into two technical pathways: filtering-based and optimization-based, each offering distinct solutions that trade off between real-time performance and accuracy.

Filtering-based methods are represented by the Multi-State Constraint Kalman Filter (MSCKF) [

18]. Its innovation lies in constructing a multi-view geometric constraint model that transforms observations of visual features across multiple frames into constraints on camera poses. This achieves computational complexity linear with the number of features, providing an efficient real-time pose estimation solution for resource-constrained embedded systems. Rovio [

19] incorporated a direct method, leveraging image pixel intensity errors to enhance performance in low-texture environments.

In the realm of optimization-based methods, VINS-Mono [

5] pioneered the combination of nonlinear optimization with IMU pre-integration technology. It achieves high-precision pose estimation for monocular visual–inertial systems by jointly optimizing visual features and inertial measurements within a sliding window. OKVIS [

6] significantly improved accuracy and reduced cumulative error through nonlinear optimization and keyframe techniques. Furthermore, the visual–inertial extension of ORB-SLAM [

15], particularly within the ORB-SLAM3 [

20] framework, further optimizes long-term localization accuracy by incorporating loop closure detection.

Although these methods demonstrate excellent performance on benchmarks such as public datasets, their reliance on hand-crafted feature extractors and motion models makes them less capable of handling complex nonlinear dynamics or sensor noise, which limits their applicability in highly dynamic environments.

2.3. Deep Learning-Based Visual–Inertial Navigation Methods

With the rise in deep learning, end-to-end VIO methods have attracted significant attention due to their powerful nonlinear modeling capabilities. Leveraging their strong nonlinear fitting ability, these methods can directly learn the pose mapping relationship from raw multi-modal data, circumventing the need for complex hand-crafted feature design and error model assumptions inherent in traditional filtering or optimization approaches. VINet [

11] pioneered the use of VIO as a sequence-to-sequence learning task. Subsequent works like DeepVIO [

12] improved performance by introducing deeper network architectures.

However, these deep learning methods still face challenges in practical applications. Firstly, feature extraction often lacks generalizability in scenarios with noisy IMU data or low-resolution images, leading to performance degradation [

21]. Secondly, while deeper networks can enhance accuracy, they often come with a substantial increase in computational complexity, making it difficult to meet the resource constraints of UAV onboard platforms. In response to these challenges, various methods have been successively proposed, such as incorporating velocity constraints [

22], integrating deep learning with traditional methods [

23], and online continual learning [

24]. Therefore, balancing accuracy and efficiency, while enhancing the capability of deep learning models to process multi-modal data, has become a key research direction in the VIO field [

25,

26].

3. Research Method

This paper proposes an end-to-end deep learning framework named TSFNet, whose core innovation lies in its decoupling design that separately handles two critical stages: intra-frame multi-modal fusion and inter-frame temporal modeling. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the architecture consists of two main phases: The first stage performs intra-frame adaptive multi-modal fusion. At this stage, the network processes a single-frame image and its corresponding IMU data window in parallel. A lightweight visual encoder and a bidirectional inertial encoder extract spatial features and motion features, respectively. These features are then adaptively weighted and fused via a gated fusion unit (GFU), generating a rich multi-modal representation that is robust to sensor noise. The second stage focuses on inter-frame temporal dynamics modeling. The fused features output from the first stage are organized into sequences and fed into a dedicated temporal modeling network. This network explicitly learns the continuity and dynamic variations in the UAV’s motion over time, ultimately regressing a high-accuracy pose sequence. This decoupled design paradigm enables the network to first concentrate on overcoming challenges such as motion blur and weak textures in individual frames. It then models the smoothness and temporal consistency of the motion trajectory at the sequence level. As a result, the system’s accuracy and robustness are significantly enhanced.

3.1. Stage 1: Intra-Frame Adaptive Multi-Modal Fusion

The objective of this stage is to generate an optimal multi-modal feature representation at each individual timestep.

3.1.1. Visual Feature Encoder

The visual encoder is responsible for extracting rich spatial hierarchical features from a single RGB image. To balance model performance with computational efficiency, this paper adopts MobileNetV3-Small [

27] as the visual backbone network. As shown in

Figure 2, its core advantages lie in the use of inverted residual structures and a lightweight Squeeze-and-Excitation attention mechanism, which enable it to maintain strong representational capacity while significantly reducing the number of model parameters and computational complexity. To capture visual information across different semantic levels—from low-level to high-level features—the feature extraction process is explicitly divided into three consecutive feature blocks. This hierarchical processing strategy allows the model to progressively distill the most valuable abstract representations for pose estimation from the raw pixels. Specifically, for an input image

at timestamp t, the feature extraction process can be formally described as follows:

Here, represents the visual feature vector obtained from the visual encoder. This vector condenses multi-level key information—ranging from low-level textures to high-level semantics—from the current visual frame, providing high-quality visual input for the subsequent multi-modal fusion module.

3.1.2. Inertial Motion Encoder

The Inertial Motion Encoder is designed to extract fine-grained motion dynamic priors from a short-time window of IMU data corresponding to the current image frame. Its core structure employs a Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (Bi-GRU) network [

28] and a Temporal Attention module. The bidirectional structure is adopted at this stage because the IMU encoder processes a complete short-term data window corresponding to a single image frame. This implies that when processing any time point within this window, all information from both its past and future is known. Therefore, The Bi-GRU processes the IMU sequence in parallel through both forward and backward recurrent units, integrating motion context information from before and after the current timestep. This enables a more comprehensive characterization of the instantaneous motion state, as illustrated in

Figure 3. Subsequently, the Temporal Attention module performs a weighted aggregation of the frame-level features output by the Bi-GRU by learning a weight distribution across the sequence dimension. This allows the model to adaptively focus on the key temporal segments within the IMU window that contribute the highest information gain, while suppressing redundant or noisy components. The final output is a compact and informationally complete inertial motion feature vector

.

3.1.3. Gated Fusion Unit

The GFU [

29] is the core module of TSFNet for achieving multi-modal fusion, designed to replace the simple feature concatenation operation commonly used in traditional late-fusion approaches. The objective of the GFU is to adaptively and dynamically balance the importance of visual and inertial features based on the characteristics of the current input data. For instance, when rapid rotation of the UAV causes severe image blur, the model should learn to rely more heavily on

, whereas in stationary or slow-moving scenarios, it should place greater trust in the high-resolution

.

(1) Feature Space Projection: To enable meaningful integration of heterogeneous visual and inertial features within a unified semantic space, they are first projected into the target output dimension via two separate fully connected layers. This step can be regarded as feature alignment and transformation.

where

and

are the input visual and inertial feature vectors, respectively.

,

and

,

are the weight matrices and bias terms of the corresponding projection layers.

(2) Gate Weight Generation: To compute the dynamic weights for fusion, the original visual and inertial features are concatenated, and the result is fed into a gating network. This network consists of two fully connected layers and a final Sigmoid activation function. The Sigmoid function compresses the output to the range (0, 1), allowing it to act as a “soft gate” that controls the information flow.

where

,

and

,

are the parameters of the gating network. Each element of the output vector

g corresponds to a weight for a specific dimension of the fused feature.

(3) Dynamically Weighted Fusion: Finally, the generated gating weights

g are used to perform a dynamically weighted fusion of the projected features. A

activation function is also applied to normalize the range of the projected features, thereby enhancing training stability.

where ⊙ denotes the Hadamard product.

3.2. Stage 2: Inter-Frame Temporal Dynamics Modeling

The core objective of this stage is to capture the long-term dependencies within the sequence of fused features generated in Stage I, thereby ensuring the smoothness and motion consistency of the output trajectory.

The feature sequence is fed into a unidirectional GRU network, as illustrated in

Figure 4. Unlike the processing of intra-frame IMU windows, inter-frame temporal modeling is a strict causal process. That is, when estimating the pose at the current moment, we can only utilize information from past and current moments, without access to any future information. To simulate this real-world temporal dependency, a unidirectional GRU is adopted at this stage. Similar to LSTM, GRU employs a gating mechanism to control information flow, thereby effectively maintaining and updating the hidden state. The GRU primarily consists of an update gate and a reset gate, with its operational principles detailed below: The update gate

is calculated as follows:

where

is the output of the update gate,

and

are learned weight parameters, and

is the Sigmoid activation function.

The reset gate

is calculated as follows:

where

is the output of the reset gate, and

and

are learned weight parameters.

The candidate hidden state

is calculated as follows:

where

is the candidate hidden state,

and

are learned weight parameters, and tanh is the hyperbolic tangent function.

The final hidden state

is updated as follows:

where

is the hidden state at the current timestep and

is the value of the update gate.

3.3. Objective Function

Visual–Inertial Odometry pose estimation is a typical multi-task learning problem that requires simultaneous optimization of both translation and rotation objectives. To effectively balance these two tasks and enhance model robustness, this work improves upon the loss function designed in [

30], proposing an adaptively weighted hybrid loss function.

The proposed loss function consists of three components: a translation loss

, a rotation loss

, and a regularization term

. The translation loss penalizes the Euclidean distance between the predicted position and the ground truth position. It is composed of a weighted combination of L2 loss and L1 loss, as defined by the following equation:

where

denotes the L2 norm,

denotes the L1 norm, and

is a hyperparameter used to balance the contribution of the L1 and L2 losses to the translation error.

The rotation loss is designed to measure the difference between the predicted quaternion and the ground truth quaternion. To ensure computational validity, the ground truth quaternion

q is first normalized, yielding

. The rotation loss is formulated similarly to the translation loss:

To mitigate overfitting in the multi-modal fusion model and enhance its generalization capability, a L2 regularization term

on the model parameters is introduced into the loss function:

Here,

w represents the set of all learnable parameters in the model, and

is the L2 regularization coefficient, a hyperparameter controlling the strength of regularization. The final total loss function is defined as follows:

In this formulation,

and

are two learnable parameters representing the uncertainty of the translation and rotation tasks, respectively. The fixed hyperparameter

provides an initial scaling for the rotation loss on top of the adaptive weighting.

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

To validate the performance of TSFNet in visual–inertial navigation tasks, this paper conducts a series of experiments. The model is evaluated on two public datasets and compared against existing methods. Furthermore, ablation studies are performed to analyze the contribution of each component, enabling a comprehensive assessment of their effectiveness.

4.1. Dataset Description

Experiments were conducted on two public visual–inertial navigation datasets, the EuRoC MAV Dataset [

31] and the Zurich Urban MAV Dataset [

32], to evaluate the proposed TSFNet method. Each dataset was split into training and test sets with an 8:2 ratio. These two datasets are complementary in terms of scenarios, scale, and challenges, allowing for a systematic examination of the algorithm’s accuracy, robustness, and generalization capability. The EuRoC MAV dataset is collected in an indoor environment using a micro aerial vehicle (MAV). It contains 11 short trajectory sequences, with scenes ranging from a texture-rich machine hall to a Vicon room characterized by fast motion and significant illumination changes. The dataset provides strictly time-synchronized stereo images (20 Hz) and industrial-grade IMU measurements (200 Hz). Dense and accurate ground truth is supplied by a high-precision Vicon motion capture system. In this paper, experiments are performed on the Vicon room sequences; example scenes are shown in

Figure 5.

The Zurich Urban MAV Dataset was collected in a large-scale, real-world urban street environment. The dataset covers a trajectory of 2 km and contains time-synchronized high-resolution aerial images, GPS and IMU sensor data, street-level ground images, and ground truth data. Its core challenges stem from unavoidable real-world complexities: a significant number of dynamic objects, severe illumination variations caused by building shadows, repetitive or blurred textures from building facades, and harsh conditions where GPS signals are largely obstructed in most areas. Example scenes are shown in

Figure 6.

4.2. Experiment Settings

During the training process, the initial learning rate was set to 0.0001 with a learning rate decay strategy applied. The loss function employed was a custom loss designed to minimize the error between predicted and actual position and orientation values. Among these,

is set to 0.5 in the experiments, a value determined through preliminary experiments on the validation set. All experiments were conducted on a single NVIDIA A40 GPU, with both training and inference running under the CUDA 12.2 environment to ensure high computational performance. Detailed experimental hyperparameters are listed in

Table 1.

Furthermore, to comprehensively evaluate the localization accuracy of the model, this paper adopts the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of both the Absolute Trajectory Error (ATE) and the Relative Pose Error (RPE) as evaluation metrics, with both measured in meters. Among these, ATE is primarily used to assess the global consistency of the trajectory, reflecting the overall deviation between the estimated trajectory and the ground truth in the absolute coordinate system, as shown in Equation (

14). On the other hand, RPE focuses on evaluating the accuracy of relative motion estimation between adjacent poses, revealing the cumulative error characteristics of the system during local motion, as illustrated in Equations (

15) and (

16). These two metrics jointly provide a comprehensive evaluation of the algorithm’s performance from different dimensions.

where

represents the ground truth pose at timestep t;

represents the estimated pose at timestep t; n is the total number of timesteps or poses in the trajectory; and

denotes the Euclidean norm.

where

represents estimated poses,

represents ground truth poses,

is the error matrix obtained by comparing relative motions over time interval

, and trans(·) is an operator function that extracts the translation vector from a homogeneous transformation matrix.

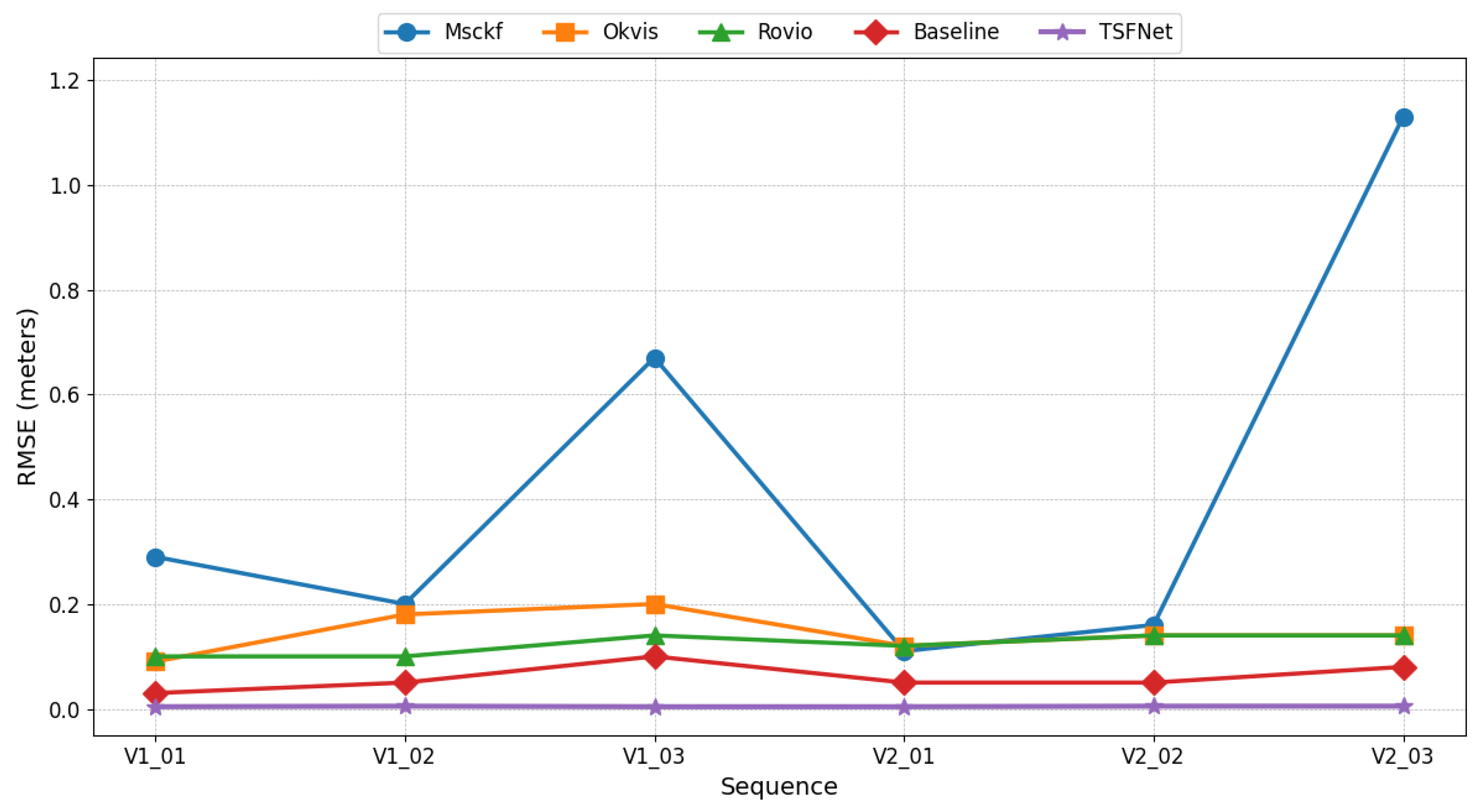

4.3. Model Performance

This paper compares TSFNet against several VIO algorithms, including the filter-based methods MSCKF [

18] and ROVIO [

19], the optimization-based method OKVIS [

6], and the data-driven baseline model [

23]. The quantitative comparison results are presented in

Figure 7.

As clearly shown by the experimental results in

Figure 7, the proposed TSFNet achieves the lowest RMSE values across the Vicon room sequences of the EuRoC dataset. Notably, it demonstrates superior performance on challenging sequences like V1_03 and V2_03, where traditional methods exhibit significant performance degradation. This advantage is primarily attributed to the synergistic effect between the proposed two-stage decoupled fusion architecture and the adaptive robust loss function, which collectively ensure the generation of highly accurate and temporally consistent trajectory estimates.

To further evaluate the model’s performance over long distances, this paper assesses TSFNet, baseline models, and the SelectFusion model on the Zurich Urban MAV dataset. For fair comparison, SelectFusion is uniformly adapted to predict absolute pose and uses single-frame image input. This dataset contains more complex urban scenarios and larger-scale motion, with experimental results shown in

Table 2.

As can be seen from

Table 2, TSFNet achieves superior performance on this dataset with an RMSE of 0.254 m, representing an error reduction of over 62% compared to the baseline model’s 0.669 m. This result clearly demonstrates that the multi-modal fusion and temporal modeling strategies learned by TSFNet are effective not only for short-range indoor positioning but also for long-range outdoor localization.

Furthermore, the predicted trajectories of the proposed TSFNet method on the EuRoC and Zurich Urban MAV datasets are visualized in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, respectively.

4.4. Model Efficiency

To further validate the lightweight nature and computational efficiency of TSFNet, we compare its efficiency against baseline models.

Table 3 presents the comparison results in terms of the number of parameters and Floating Point Operations (FLOPs).

As shown in

Table 3, in addition to its superior accuracy, TSFNet demonstrates significant advantages in computational efficiency, which is crucial for deployment on resource-constrained platforms. The proposed model requires only 4.823 Millions parameters and 6.331 GFLOPs. Compared to the baseline models, this represents a substantial reduction of 76.65% in parameters and 24.30% in computational load. This notable efficiency does not stem from a single module but is the result of a systematic lightweight design implemented across three core components of the network: Firstly, an efficient MobileNetV3-Small backbone is adopted for feature extraction. Secondly, at the multi-modal fusion stage, a gated fusion unit is introduced, replacing traditional high-dimensional concatenation with minimal parameter overhead. Finally, for temporal modeling, a GRU structure with lower computational cost is employed. In summary, the design of TSFNet strongly demonstrates that high-precision pose estimation and a lightweight model are not mutually exclusive. It maintains excellent performance while significantly reducing computational resource requirements, providing a solid technical foundation for deploying end-to-end VIO on real-world embedded platforms such as UAVs.

4.5. Analysis of Gated Fusion Mechanism

To thoroughly validate the adaptive fusion capability of the GFU, this paper conducts a visual analysis of its core gating weight

g, as shown in

Figure 10. The figure illustrates the dynamic relationship between the mean value of

g and the true angular velocity of the UAV in the V1_03_difficult validation sequence from the EuRoC dataset.

As shown in

Figure 10, the gating weight

g of the GFU exhibits a complex nonlinear dynamic relationship with the UAV’s angular velocity. In the later stages of a maneuver, when the angular velocity reaches its peak or undergoes high-frequency oscillations, the value of

g decreases significantly as expected, indicating that the model successfully suppresses low-quality visual information.

A particularly noteworthy phenomenon is observed during the initial phase of a turn: although the angular velocity continues to rise, the gating weight g also shows a brief synchronous increase. We argue that this reveals a more advanced decision-making strategy learned by the GFU: it evaluates not only the quality of visual information but also its information gain. In the early stage of a maneuver, the substantial information gain brought by the new scene outweighs the negative impact of motion blur. Consequently, the model chooses to temporarily increase its reliance on visual input to “absorb” features from the new environment.

This ability to intelligently trade off between “information quality” and “information gain” demonstrates that the GFU is not a simple threshold switch but has learned a more robust and physically intuitive dynamic fusion model.

4.6. Ablation Study

To evaluate the effectiveness of individual components within TSFNet, a systematic ablation study was conducted on the EuRoC V1_03_difficult and Zurich Urban MAV datasets. The impact on model performance was observed by incrementally integrating key modules. The results are summarized in

Table 4. Here, a ✔ signifies an enabled component.

As shown in

Table 4, the Base model, which employs a simple feature concatenation strategy, serves as the performance baseline. Model performance improves progressively with the addition of key modules. Notably, when the Temporal Attention module for IMU data is introduced alone, performance slightly degrades—the RMSE on Zurich Urban MAV increases from 0.402 to 0.501. This suggests that without guidance from an advanced fusion strategy, the attention mechanism may fail to focus on critical temporal information and could even amplify noise. In contrast, integrating the GFU alone brings a significant performance improvement, reducing RMSE to 0.347. This demonstrates that adaptive gated fusion is a core driver of performance enhancement. When temporal attention and gated fusion work together, performance is further improved, with RMSE decreasing to 0.306. This reveals a synergistic effect. Finally, the Full model, which incorporates explicit inter-frame temporal modeling, achieves optimal performance.

To validate the effectiveness of our proposed adaptive hybrid loss function, we replaced the loss function in the Full Model with a standard MSE Loss for comparison. Experimental results show that the model performance deteriorates sharply when using MSE Loss, with RMSE soaring from 0.250 to 0.458. This irrefutably proves that our designed loss function plays a crucial role in balancing multi-task learning and enhancing optimization robustness.

In summary, the ablation study strongly validates the rationality of the TSFNet architecture, demonstrating the hierarchical contributions of adaptive fusion as the foundation, attention mechanism as the enhancer, and temporal modeling as the safeguard.

5. Conclusions

This paper introduced TSFNet, a novel two-stage decoupled fusion network, to address the prevailing challenges in robustness, efficiency, and dynamic fusion capability within existing deep learning-based VIO methods. The core contribution of this research is the validation of a new design paradigm: decoupling the complex end-to-end VIO task into two distinct and more tractable sub-problems—intra-frame adaptive fusion and inter-frame temporal modeling. Experiments demonstrated that by leveraging a lightweight network architecture and employing a GFU for explicit, source-level control over multi-modal data quality, TSFNet significantly enhances localization accuracy in complex dynamic scenes while maintaining high computational efficiency. Its superior performance on public datasets, including EuRoC and Zurich Urban MAV, substantiates the efficacy of this decoupled, dynamic fusion strategy.

Despite these encouraging results, we also acknowledge the limitations of our work. Firstly, as a pure odometry system, TSFNet is inherently unable to eliminate drift that accumulates over time. Secondly, its performance ceiling is constrained by the representational capacity of the visual encoder; in scenarios with extreme illumination or a severe lack of texture, performance may degrade even with the GFU’s dynamic regulation. Lastly, the current GFU primarily infers the motion state from IMU data; consequently, its ability to perceive degradations in visual information quality caused by external environmental factors is limited.

These limitations also illuminate several promising directions for future work. First, integrating the high-performance TSFNet front-end with a graph-optimization-based global pose back-end, and exploring an end-to-end loop closure mechanism, is a critical next step toward constructing a complete and efficient SLAM system capable of mitigating cumulative error. Second, incorporating more advanced visual backbones or self-supervised learning paradigms could enhance the model’s generalization capabilities in unseen and visually degraded environments. Third, integrating scene understanding modules, such as semantic segmentation, into our framework would enable the GFU’s decisions to be informed not only by ego-motion but also by the dynamics of the external scene, thereby achieving a more sophisticated level of intelligent multi-modal fusion. These explorations will continue to propel VIO technology toward the objectives of enhanced robustness, intelligence, and efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W., J.L. and X.Y.; Methodology, J.L., Y.G., M.Z. and X.Y.; Software, Y.G. and M.Z.; Validation, J.L., Y.L, Y.G., M.Z. and B.P.; Formal analysis, J.L., M.Z. and X.Y.; Investigation, Y.G., M.Z. and B.P.; Resources, B.P.; Data curation, Y.G. and B.P.; Writing—original draft, S.W.; Writing—review and editing, J.L., Y.L., Y.G. and X.Y.; Supervision, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Key Research and Development Program of China grant number 2025YFE0103200.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Author Shuai Wang was employed by Fushun China Coal Technology Engineering Testing Center Co., Ltd., Yuxi Gan was employed by WeiKang (Shenzhen) Intelligence Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Scaramuzza, D.; Achtelik, M.C.; Doitsidis, L.; Friedrich, F.; Kosmatopoulos, E.; Martinelli, A. Vision-controlled micro flying robots: From system design to autonomous navigation and mapping in GPS-denied environments. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2014, 21, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, C.; Pizzoli, M.; Scaramuzza, D. SVO: Fast semi-direct monocular visual odometry. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Hong Kong, China, 31 May–7 June 2014; pp. 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, C.; Carlone, L.; Della ert, F.; Scaramuzza, D. On-manifold preintegration for real-time visual-inertial odometry. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2017, 33, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Mourikis, A.I. High-precision, Consistent EKF-based Visual-Inertial Odometry. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2013, 32, 690–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Li, P.; Shen, S. Vins-mono: A robust and versatile monocular visual-inertial state estimator. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2018, 34, 1004–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leutenegger, S.; Lynen, S.; Bosse, M.; Siegwart, R.; Furgale, P. Keyframe-based visual-inertial odometry using nonlinear optimization. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2015, 34, 314–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, C.; Zhang, Z.; Gassner, M.; Werlberger, M.; Scaramuzza, D. SVO: Semidirect visual odometry for monocular and multicamera systems. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2017, 33, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Clark, R.; Wen, H.; Trigoni, N. Deepvo:Towards end-to-end visual odometry with deep recurrent convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, 29 May–3 June 2017; pp. 2043–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Clark, R.; Wen, H.; Trigoni, N. End-to-end, sequence-to-sequence probabilistic visual odometry through deep neural networks. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2018, 37, 513–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamwell, E.J.; Lindgren, K.; Leung, S.; Nothwang, W.D. Unsupervised deep visual-inertial odometry with online error correction for rgb-d imagery. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2019, 42, 2478–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.; Wang, S.; Wen, H.; Trigoni, N.; Markham, A. VINet: Visual-inertial odometry as a sequence-to-sequence learning problem. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Lin, Y.; Du, G.; Lian, S. DeepVIO: Self-supervised Deep Learning of Monocular Visual Inertial Odometry using 3D Geometric Constraints. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Macau, China, 4–8 November 2019; pp. 6906–6913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, G.; Murray, D. Parallel tracking and mapping for small AR workspaces. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR), Nara, Japan, 13–16 November 2007; pp. 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.; Schöps, T.; Cremers, D. LSD-SLAM: Large-scale direct monocular SLAM. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; pp. 834–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mur-Artal, R.; Montiel, J.M.M.; Tardos, J.D. ORB-SLAM: A versatile and accurate monocular SLAM system. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2015, 31, 1147–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Xu, A.; Xu, X.; Liu, M. Modeling and Compensation of Inertial Sensor Errors in Measurement Systems. Electronics 2023, 12, 2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julier, S.J.; Uhlmann, J.K. New extension of the Kalman filter to nonlinear systems. In Proceedings of the Signal Processing, Sensor Fusion, and Target Recognition VI, Orlando, FL, USA, 21–25 April 1997; Volume 3068, pp. 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourikis, A.I.; Roumeliotis, S.I. A Multi-State Constraint Kalman Filter for Vision-aided Inertial Navigation. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Rome, Italy, 10–14 April 2007; pp. 3565–3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloesch, M.; Omari, S.; Hutter, M.; Siegwart, R. Robust visual inertial odometry using a direct EKF-based approach. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Hamburg, Germany, 28 September–2 October 2015; pp. 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, C.; Elvira, R.; Rodríguez, J.J.G.; Montiel, J.M.M.; Tardós, J.D. ORB-SLAM3: An Accurate Open-Source Library for Visual, Visual-Inertial, and Multimap SLAM. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2021, 37, 1874–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinho, L.R.; Ricardo, N.M.; Pereira, M.I.; Hiolle, A.; Pinto, A.M. A Practical Survey on Visual Odometry for Autonomous Driving in Challenging Scenarios and Conditions. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 72182–72205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, P.; Zhou, P.; Meng, Z. Robust neural visual inertial odometry with deep velocity constraint. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 4627–4634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solodar, D.; Klein, I. VIO-DualProNet: Visual-inertial odometry with learning based process noise covariance. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Xu, C. Adaptive VIO: Deep Visual-Inertial Odometry with Online Continual Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Pan, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, Z. CMIF-VIO: A Novel Cross Modal Interaction Framework for Visual Inertial Odometry. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 2598–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yan, H.; Wu, G. RWKV-VIO: An Efficient and Low-Drift Visual–Inertial Odometry Using an End-to-End Deep Network. Sensors 2025, 25, 5737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chu, G.; Chen, L.C.; Chen, B.; Tan, M.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, R.; Vasudevan, V.; et al. Searching for MobileNetV3. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 1314–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M.; Paliwal, K.K. Bidirectional recurrent neural networks. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 1997, 45, 2673–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arevalo, J.; Solorio, T.; Montes-y-Gómez, M.; Pérez-Couti?o, M. Gated Multimodal Units for Information Fusion. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1702.01992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, F.; Anandkumar, A.; Murray, R.M. Learning pose estimation for UAV autonomous navigation and landing using visual-inertial sensor data. In Proceedings of the 2020 American Control Conference (ACC), Denver, CO, USA, 1–3 July 2020; pp. 2961–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burri, M.; Nikolic, J.; Gohl, P.; Schneider, T.; Rehder, J.; Omari, S.; Achtelik, M.W.; Siegwart, R. The EuRoC micro aerial vehicle datasets. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2016, 35, 1157–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdik, A.L.; Till, C.; Scaramuzza, D. The Zurich urban micro aerial vehicle dataset. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2017, 36, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, Y.; Liu, M. Selectfusion: A generic framework to selectively learn multisensory fusion. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.13077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).