A Transformer-Based Multi-Task Learning Model for Vehicle Traffic Surveillance

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We present a high-performance transformer-based MTL model for VTS systems that jointly addresses detection, tracking, and classification.

- We perform extensive experiments on standard VTS benchmarks demonstrate that the proposed approach achieves competitive state-of-the-art performance across tasks.

- To the best of our knowledge, this is the first end-to-end MTL model for vehicle detection, tracking, and classification, providing a scalable and generalizable solution for real-world traffic analysis.

2. Related Work

2.1. Moving Vehicle Detection Task

- Appearance-based approaches model vehicle appearance using handcrafted descriptors such as color and edges [21], the Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) [22], Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT) [23], Haar-like features [24], Local Binary Patterns (LBPs) [25,26], and wavelet-based representations [27]. Other studies have combined multiple descriptors using tensor decompositions, including Tucker decomposition to fuse HOG, LBP, and Four-Direction Features (FDFs) for vehicle detection at night [28].

- DL-based approaches have recently improved vehicle detection by automatically learning robust appearance features, overcoming the limitations of handcrafted descriptors. Notable models include YOLO [39], Faster R-CNN [40], and Mask R-CNN [41]. More recently, transformer-based architectures like Detection Transformer (DETR) [42] introduced an end-to-end detection paradigm that formulates object detection as a direct set prediction problem, leveraging attention mechanisms to capture long-range spatial dependencies and global contextual relationships across the entire scene.

Occlusion Handling

- Heuristic-based approaches typically exploit prior knowledge of vehicle geometry and motion—such as shape convexity, symmetry, aspect ratio, and bounding box overlapping—to detect occluded vehicles [9,43,44,45,46]. However, such assumptions often fail in complex scenarios involving heavy occlusion, irregular vehicle shapes, and unpredictable motion patterns.

2.2. Vehicle Tracking Task

- Motion-based methods model vehicle dynamics using IoU heuristics or probabilistic filters such as Kalman and particle filters, followed by assignment solvers like the Hungarian algorithm [9,55,56,57]. Classical motion-based trackers include SORT, which uses Kalman filtering and the Hungarian algorithm to estimate bounding box states and associate tracks in real-time [58], and ByteTrack, which extends SORT by also associating low-confidence detections to maintain consistent tracking in crowded or occluded scenes [59]. Nevertheless, they often fail under abrupt maneuvers, irregular trajectories, or heavy occlusions.

- DL methods have improved tracking robustness by leveraging automatically learned feature embeddings for better discrimination and data association [60]. DeepSORT extends SORT by extracting appearance features via a CNN for re-identification after occlusions [61]. Other neural network approaches include Tracktor [62] and CenterTrack [63]. Transformer-based architectures—including TrackFormer [17] and TransTrack [64]—leverage attention mechanisms to capture long-term temporal dependencies, enabling more robust tracking compared to traditional approaches such as Kalman filters, which rely on simplified observation models. Recently, MOTR [19] introduced an end-to-end detection and tracking pipeline with track queries for identity propagation, leveraging transformers to learn nonlinear temporal dependencies directly from the data. MOTRv2 [65] have further extended this framework by incorporating a pretrained YOLOv5 backbone to enhance detection performance.

2.3. Vehicle Classification Task

- Appearance-based approaches model vehicle appearance using handcrafted features—including Image Moments, HOG, SIFT, and color histograms—that capture discriminative visual cues such as shape, texture, and color for different vehicle categories. Subsequently, these features are fed to traditional machine learning classifiers (e.g., support vector machines [9]), or clustering techniques (e.g., K-means [66]). However, the performance of such methods strongly depends on the quality and expressiveness of the handcrafted features.

- DL approaches leverage CNNs to automatically learn discriminative vehicle features directly from images. Modern architectures, including YOLO [39], VGGNet [67], ResNet [68], DenseNet [69], and EfficientNet [70], have consistently outperformed traditional methods, enabling robust intra- and inter-class classification in challenging traffic scenarios.

3. Problem Statement and Mathematical Formulation

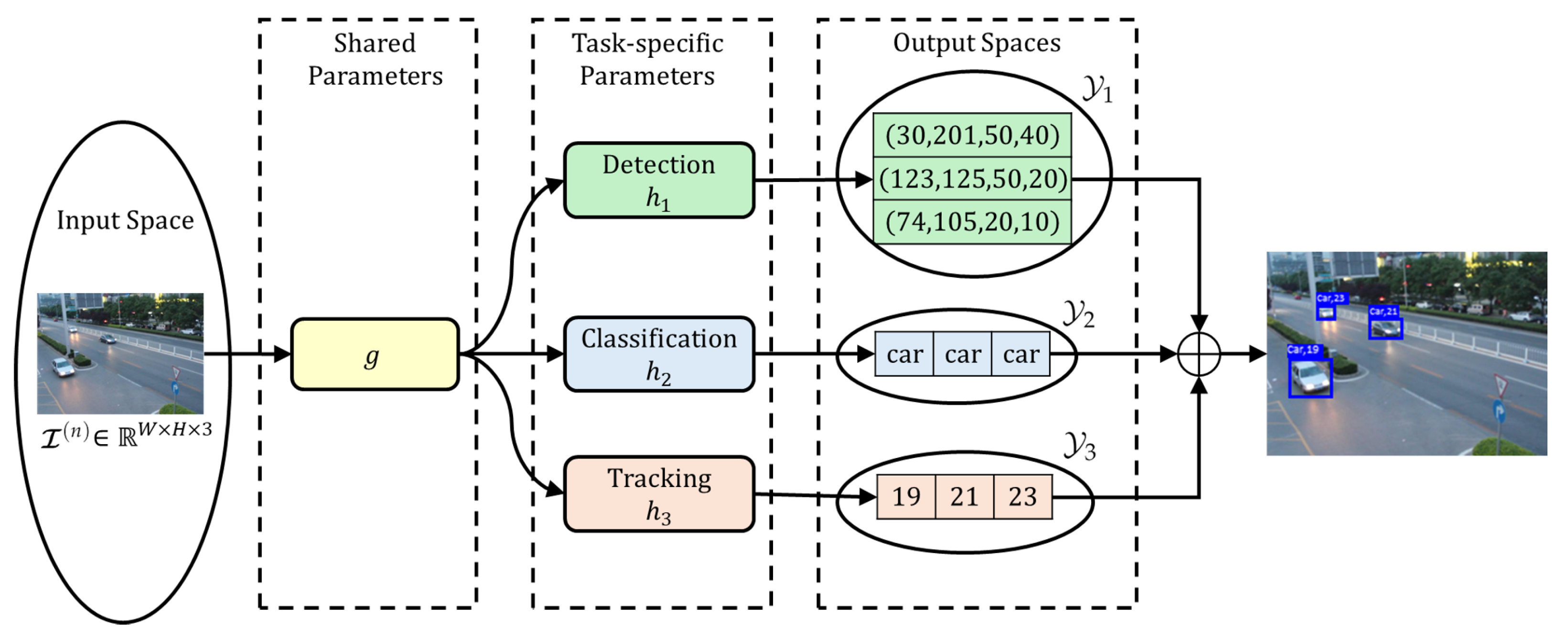

3.1. Problem Statement

3.2. Mathematical Formulation

- Vehicle detection (): predicts the bounding box corresponding to the k-th vehicle on the road in frame n. Each bounding box is parameterized by the pixel coordinates of its top-left corner and its spatial size (width and height).

- Vehicle classification (): assigns a category label to the k-th vehicle detected in the frame n.

- Vehicle tracking (): maintains temporal identity for the k-th vehicle detected in the frame n.

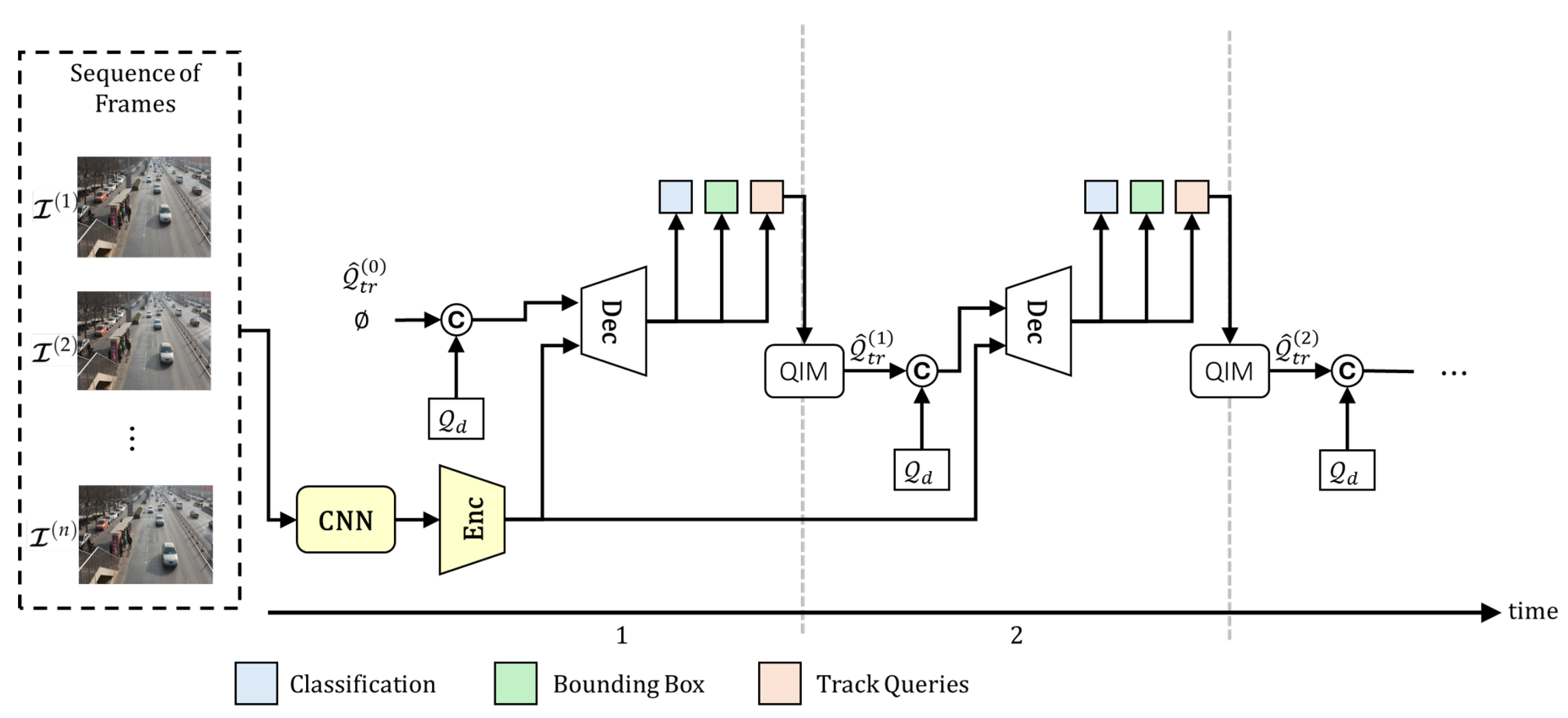

4. Transformer-Based Multi-Task Learning Model for Vehicle Traffic Surveillance

4.1. Proposed Model

- Detection queries are matched exclusively to newborn vehicles using bipartite matching between predictions of detect queries, , and the ground truth of newborn objects, , at frame n.

- Tracking queries are matched according to their temporal identity consistency, inheriting their assignments from the previous frame to preserve temporal identity.

4.2. Multi-Task Learning Framework

5. Experimental Results

5.1. Dataset Description

5.2. Quantitative Results

6. Discussion

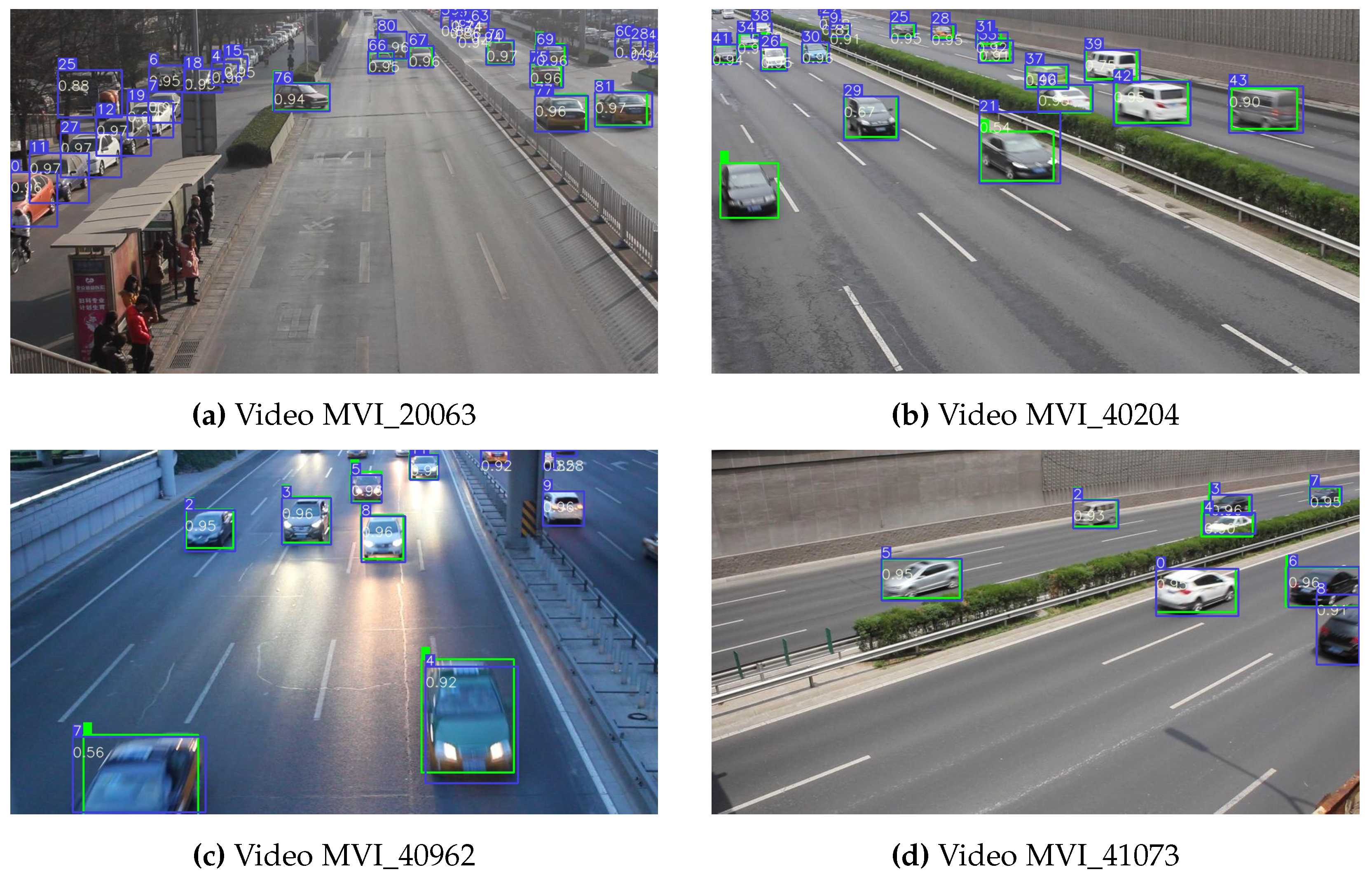

6.1. Failure Modes and Operating Conditions

- (a)

- Density and occlusion dominate errors. Sequences characterized by dense traffic and frequent partial occlusions (e.g., MVI_40212 and MVI_40204) show a lower recall and a higher IDS. This is consistent with identity drops caused by lower spatial visibility, rather than tracker confusion.

- (b)

- Precision is uniformly strong. All sequences maintain precision , with several above (MVI_20064: ; MVI_20033: ; and MVI_40962: ). This suggests that false positives are well handled, and further improvements should focus on increasing recall while preserving precision.

- (c)

- Association is reliable when observations persist. High IDP across sequences indicates that the association cost is well calibrated for temporally consistent tracks. Drops in IDR occur mostly when targets leave the field of view or are heavily truncated.

6.2. Implications and Future Improvements

- Occlusion-aware re-identification. Incorporating long-range appearance embeddings with explicit occlusion modeling and temporal memory (e.g., tracklet-level re-ID with motion gating) should raise IDR and reduce IDS in clips with frequent hide-and-reveal events.

- Recall-oriented detection tuning. Threshold calibration and hard-example mining targeted at small, truncated, or partially visible vehicles can improve recall while preserving the current precision regime.

6.3. Summary

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hassan, M.A.; Javed, R.; Farhatullah; Granelli, F.; Gen, X.; Rizwan, M.; Ali, S.H.; Junaid, H.; Ullah, S. Intelligent Transportation Systems in Smart City: A Systematic Survey. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Robotics and Automation in Industry (ICRAI), Peshawar, Pakistan, 3–5 March 2023; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elassy, M.; Al-Hattab, M.; Takruri, M.; Badawi, S. Intelligent transportation systems for sustainable smart cities. Transp. Eng. 2024, 16, 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonix-Gleason, L.E.; Del-Puerto-Flores, J.A.; Castillo-Soria, F.R.; Parra-Michel, R.; Campos, F.P. Neural Network Aided M-PSK Detection in 802.11P V2V OFDM Systems Under ICI Conditions. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2025, 14, 3420–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Puerto-Flores, J.A.; Castillo-Soria, F.R.; Gutiérrez, C.A.; Peña-Campos, F. Efficient Index Modulation-Based MIMO OFDM Data Transmission and Detection for V2V Highly Dispersive Channels. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Shukla, H.; Rajalakhsmi, P. V2X Enabled Emergency Vehicle Alert System. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.19402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Hak, M.; Al-Holou, N.; Bazzi, Y.; Tamer, M.A. Predictive Vehicle Route Optimization in Intelligent Transportation Systems. Int. J. Data Sci. Technol. 2019, 5, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikonda, P.; Yerrapragada, A.K.; Annasamudram, S.S. Intelligent traffic management system. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Conference on Sustainable Utilization and Development in Engineering and Technology (STUDENT), Semenyih, Malaysia, 20–21 October 2011; pp. 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermosillo-Reynoso, F.; Torres-Roman, D.; Santiago-Paz, J.; Ramirez-Pacheco, J. A Novel Algorithm Based on the Pixel-Entropy for Automatic Detection of Number of Lanes, Lane Centers, and Lane Division Lines Formation. Entropy 2018, 20, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez-Pupo, R.; Sierra-Romero, A.; Torres-Roman, D.; Shkvarko, Y.V.; Santiago-Paz, J.; Gómez-Gutiérrez, D.; Robles-Valdez, D.; Hermosillo-Reynoso, F.; Romero-Delgado, M. Vehicle Detection with Occlusion Handling, Tracking, and OC-SVM Classification: A High Performance Vision-Based System. Sensors 2018, 18, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Hu, W. Robust Vehicle Detection and Counting Algorithm Adapted to Complex Traffic Environments with Sudden Illumination Changes and Shadows. Sensors 2020, 20, 2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruana, R. Multitask Learning. Mach. Learn. 1997, 28, 41–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawshaw, M. Multi-Task Learning with Deep Neural Networks: A Survey. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.09796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdillah, A.F.; Hamidi, M.Z.; Esti Anggraeni, R.N.; Sarno, R. Comparative Study of Single-task and Multi-task Learning on Research Protocol Document Classification. In Proceedings of the 2021 13th International Conference on Information & Communication Technology and System (ICTS), Surabaya, Indonesia, 20–21 October 2021; pp. 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Sarkis, M.; Lu, G. Multi-Task Learning for Single Image Depth Estimation and Segmentation Based on Unsupervised Network. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Paris, France, 31 May–31 August 2020; pp. 10788–10794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Su, W.; Lu, L.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Dai, J. Deformable DETR: Deformable Transformers for End-to-End Object Detection. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2010.04159. [Google Scholar]

- Meinhardt, T.; Kirillov, A.; Leal-Taixé, L.; Feichtenhofer, C. TrackFormer: Multi-Object Tracking with Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 8834–8844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermosillo-Reynoso, F.; Torres-Roman, D. A Tensor Space for Multi-View and Multitask Learning Based on Einstein and Hadamard Products: A Case Study on Vehicle Traffic Surveillance Systems. Sensors 2024, 24, 7463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, F.; Dong, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhang, X.; Wei, Y. MOTR: End-to-End Multiple-Object Tracking with Transformer. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2105.03247. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhan, J.; Duan, C.; Guan, X.; Lu, P.; Yang, K. A Review of Vehicle Detection Techniques for Intelligent Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 3811–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, L.W.; Hsieh, J.W.; Fan, K.C. Vehicle Detection Using Normalized Color and Edge Map. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2007, 16, 850–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Yu, M.; Yu, Y.; Fan, L. Real-time vehicle detection using histograms of oriented gradients and AdaBoost classification. Optik 2016, 127, 7941–7951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, D.G. Distinctive Image Features from Scale-Invariant Keypoints. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2004, 60, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, P.; Jones, M. Rapid object detection using a boosted cascade of simple features. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2001, Kauai, HI, USA, 8–14 December 2001; Volume 1, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, T.; Pietikainen, M.; Maenpaa, T. Multiresolution gray-scale and rotation invariant texture classification with local binary patterns. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2002, 24, 971–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassaballah, M.; Kenk, M.A.; El-Henawy, I.M. Local binary pattern-based on-road vehicle detection in urban traffic scene. Pattern Anal. Appl. 2020, 23, 1505–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallat, S. A theory for multiresolution signal decomposition: The wavelet representation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1989, 11, 674–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, H.; Chen, L.; Chan, L.L.H.; Cheung, R.C.C.; Yan, H. Feature Selection Based on Tensor Decomposition and Object Proposal for Night-Time Multiclass Vehicle Detection. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man, Cybern. Syst. 2019, 49, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucchiara, R.; Piccardi, M.; Mello, P. Image analysis and rule-based reasoning for a traffic monitoring system. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2000, 1, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, H.A.; Sheikh, U.U.; Ahmad, R.B.; Zain, A.S.M.; Ariffin, W.N.F.W. Vehicle speed detection using frame differencing for smart surveillance system. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Information Science, Signal Processing and their Applications (ISSPA 2010), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 10–13 May 2010; pp. 630–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccardi, M. Background subtraction techniques: A review. In Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics (IEEE Cat. No.04CH37583), The Hague, The Netherlands, 10–13 October 2004; Volume 4, pp. 3099–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauffer, C.; Grimson, W. Adaptive background mixture models for real-time tracking. In Proceedings of the 1999 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (Cat. No PR00149), Fort Collins, CO, USA, 23–25 June 1999; Volume 2, pp. 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, B.; Velastin, S. Automatic congestion detection system for underground platforms. In Proceedings of the 2001 International Symposium on Intelligent Multimedia, Video and Speech Processing, ISIMP 2001 (IEEE Cat. No.01EX489), Hong Kong, China, 4 May 2001; pp. 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, N.; Rosario, B.; Pentland, A. A Bayesian computer vision system for modeling human interactions. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2000, 22, 831–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Huang, W.; Gu, I.Y.H.; Tian, Q. Foreground object detection from videos containing complex background. In Proceedings of the Eleventh ACM International Conference on Multimedia, New York, NY, USA, 2 November 2003; MULTIMEDIA ’03. pp. 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, Q. Moving vehicle detection based on optical flow estimation of edge. In Proceedings of the 2015 11th International Conference on Natural Computation (ICNC), Zhangjiajie, China, 15–17 August 2015; pp. 754–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candes, E.J.; Li, X.; Ma, Y.; Wright, J. Robust Principal Component Analysis? arXiv 2009, arXiv:0912.3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Feng, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, W.; Lin, Z.; Yan, S. Tensor Robust Principal Component Analysis with a New Tensor Nuclear Norm. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 42, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1506.01497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2961–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Vedaldi, A., Bischof, H., Brox, T., Frahm, J.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Yung, N.; Lai, A. Detection of vehicle occlusion using a generalized deformable model. In Proceedings of the ISCAS ’98, 1998 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (Cat. No.98CH36187), Monterey, CA, USA, 31 May–3 June 1998; Volume 4, pp. 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oneata, D.; Revaud, J.; Verbeek, J.; Schmid, C. Spatio-temporal Object Detection Proposals. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2014, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; Fleet, D., Pajdla, T., Schiele, B., Tuytelaars, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 737–752. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, H.N.; Pham, L.H.; Tran, D.N.N.; Ha, S.V.U. Occlusion vehicle detection algorithm in crowded scene for Traffic Surveillance System. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on System Science and Engineering (ICSSE), Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 21–23 July 2017; pp. 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Wang, L.; Meng, G.; Xiang, S.; Pan, C. Vision-Based Occlusion Handling and Vehicle Classification for Traffic Surveillance Systems. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2018, 10, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Yu, Y.; Wang, F.; Liu, W.; He, S.; Pan, J. Visualizing the Invisible: Occluded Vehicle Segmentation and Recovery. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.09381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Sun, R.; Shu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Q. Occlusion-Aware Detection and Re-ID Calibrated Network for Multi-Object Tracking. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.15795. [Google Scholar]

- Plaen, P.F.D.; Marinello, N.; Proesmans, M.; Tuytelaars, T.; Van Gool, L. Contrastive Learning for Multi-Object Tracking with Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2024; pp. 6853–6863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfipoor, M.; Zafarqandi, M.J.S.; Mohammadi, S. Real-Time Occlusion-Aware Object Tracking. In Proceedings of the 2025 Fifth National and the First International Conference on Applied Research in Electrical Engineering (AREE), Ahvaz, Iran, 4–5 February 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Huang, Q. Multi-object tracking based on graph neural networks. Multimed. Syst. 2025, 31, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Almageed, W.; Davis, L.S. Robust Appearance Modeling for Pedestrian and Vehicle Tracking. In Multimodal Technologies for Perception of Humans; Stiefelhagen, R., Garofolo, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 209–215. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.h.; Lee, K.h.; Cha, K.c.; Kwon, J.s.; Kim, D.w.; Song, H.k. Vehicle Tracking using Template Matching based on Feature Points. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE International Conference on Information Reuse & Integration, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 16–18 September 2006; pp. 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto, K.; Yonekawa, T.; Okamoto, K. Visual vehicle tracking based on an appearance generative model. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Soft Computing and Intelligent Systems, and The 13th International Symposium on Advanced Intelligence Systems, Kobe, Japan, 20–24 November 2012; pp. 711–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalman, R.E. A New Approach to Linear Filtering and Prediction Problems. J. Basic Eng. 1960, 82, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulampalam, M.; Maskell, S.; Gordon, N.; Clapp, T. A tutorial on particle filters for online nonlinear/non-Gaussian Bayesian tracking. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2002, 50, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, H.W. The Hungarian method for the assignment problem. Nav. Res. Logist. Q. 1955, 2, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewley, A.; Ge, Z.; Ott, L.; Ramos, F.; Upcroft, B. Simple online and realtime tracking. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 25–28 September 2016; pp. 3464–3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, P.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, D.; Weng, F.; Yuan, Z.; Luo, P.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. ByteTrack: Multi-Object Tracking by Associating Every Detection Box. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2110.06864. [Google Scholar]

- Adžemović, M. Deep Learning-Based Multi-Object Tracking: A Comprehensive Survey from Foundations to State-of-the-Art. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.13457. [Google Scholar]

- Wojke, N.; Bewley, A.; Paulus, D. Simple online and realtime tracking with a deep association metric. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Beijing, China, 17–20 September 2017; pp. 3645–3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, P.; Meinhardt, T.; Leal-Taixé, L. Tracking Without Bells and Whistles. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Koltun, V.; Krähenbühl, P. Tracking Objects as Points. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Vedaldi, A., Bischof, H., Brox, T., Frahm, J.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 474–490. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, P.; Cao, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Xie, E.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, C.; Luo, P. TransTrack: Multiple Object Tracking with Transformer. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2012.15460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhang, X. MOTRv2: Bootstrapping End-to-End Multi-Object Tracking by Pretrained Object Detectors. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 22056–22065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.Y.; Tay, Y.H. Image-based Vehicle Classification System. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1204.2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely Connected Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2261–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1905.11946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sener, O.; Koltun, V. Multi-Task Learning as Multi-Objective Optimization. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1810.04650. [Google Scholar]

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.Y.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv4: Optimal Speed and Accuracy of Object Detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLOv3: An Incremental Improvement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.02767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2999–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezatofighi, H.; Tsoi, N.; Gwak, J.; Sadeghian, A.; Reid, I.; Savarese, S. Generalized Intersection Over Union: A Metric and a Loss for Bounding Box Regression. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Du, D.; Cai, Z.; Lei, Z.; Chang, M.C.; Qi, H.; Lim, J.; Yang, M.H.; Lyu, S. UA-DETRAC: A new benchmark and protocol for multi-object detection and tracking. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2020, 193, 102907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luiten, J.; Ošep, A.; Dendorfer, P.; Torr, P.; Geiger, A.; Leal-Taixé, L.; Leibe, B. HOTA: A Higher Order Metric for Evaluating Multi-object Tracking. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2021, 129, 548–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Task | Approach | Method | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection | Appearance | HOG [22] | Sensitive to lighting, occlusions, and viewpoint variations |

| SIFT [23] | Same as above | ||

| Haar-like features [24] | Same as above | ||

| LBP [25,26] | Same as above | ||

| Motion | Background subtraction [31,32,33,34] | Fails under camera motion, dynamic background, or abrupt vehicle movement | |

| Optical flow [35,36] | Same as above | ||

| Subspace models [37,38] | Same as above | ||

| DL | YOLO [39] | Requires large annotated datasets; higher computational cost | |

| Faster R-CNN [40] | Same as above | ||

| Mask R-CNN [41] | Same as above | ||

| DETR [42] | Same as above | ||

| Occlusion | Heuristic | Geometric priors [9,43,44,45,46] | Limited robustness for heavy occlusion or irregular shapes |

| DL | Feature reconstruction [47,48] | Computationally expensive; requires large datasets with occlusions | |

| Occlusion context-aware [49,50,51] | Same as above | ||

| Tracking | Appearance | Color histograms [52,53] | Sensitive to illumination, perspective changes, and occlusions |

| Texture descriptors [54] | Same as above | ||

| Motion | Kalman filter [9] | Fail in presence of nonlinear dynamics | |

| SORT [58] | Fails under abrupt maneuvers, nonlinear motion, or crowded scenes | ||

| ByteTrack [59] | Same as above | ||

| DL | DeepSORT [61] | High computational cost; requires large annotated sequences | |

| TrackFormer [17] | Same as above | ||

| MOTR [19] | Limited detection performance | ||

| Classification | Appearance | SIFT and Color histograms [9,66] | Performance limited by feature design; sensitive to occlusions |

| Image Moments [9] | Same as above | ||

| DL | YOLO, VGGNet, ResNet [39,67,68,69,70] | Requires large labeled datasets; high computational resources |

| Video | MOTA | IDS | IDP | IDR | IDF1 | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVI_40962 | 0.863 | 4 | 0.981 | 0.868 | 0.921 | 0.988 | 0.875 |

| MVI_40981 | 0.796 | 3 | 0.909 | 0.877 | 0.893 | 0.913 | 0.881 |

| MVI_40963 | 0.710 | 32 | 0.888 | 0.740 | 0.807 | 0.927 | 0.773 |

| MVI_41073 | 0.822 | 17 | 0.922 | 0.875 | 0.898 | 0.934 | 0.886 |

| MVI_20063 | 0.776 | 8 | 0.894 | 0.823 | 0.857 | 0.922 | 0.849 |

| MVI_20033 | 0.754 | 2 | 0.972 | 0.769 | 0.859 | 0.977 | 0.773 |

| MVI_40212 | 0.649 | 12 | 0.902 | 0.695 | 0.785 | 0.922 | 0.711 |

| MVI_40204 | 0.697 | 24 | 0.873 | 0.743 | 0.803 | 0.910 | 0.775 |

| MVI_20064 | 0.707 | 19 | 0.923 | 0.706 | 0.800 | 0.963 | 0.736 |

| MVI_20065 | 0.700 | 20 | 0.853 | 0.769 | 0.809 | 0.889 | 0.801 |

| Metric | MOTA | IDF1 | IDP | IDR | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.757 | 0.832 | 0.906 | 0.767 | 0.934 | 0.796 |

| Std. Dev. | 0.065 | 0.048 | 0.034 | 0.063 | 0.024 | 0.058 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hermosillo-Reynoso, F.; López-Pimentel, J.-C.; Ruiz-Ibarra, E.; García-Berumen, A.; Del-Puerto-Flores, J.A.; Gilardi-Velazquez, H.E.; Kumaravelu, V.B.; Luna-Rodriguez, L.A. A Transformer-Based Multi-Task Learning Model for Vehicle Traffic Surveillance. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3832. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233832

Hermosillo-Reynoso F, López-Pimentel J-C, Ruiz-Ibarra E, García-Berumen A, Del-Puerto-Flores JA, Gilardi-Velazquez HE, Kumaravelu VB, Luna-Rodriguez LA. A Transformer-Based Multi-Task Learning Model for Vehicle Traffic Surveillance. Mathematics. 2025; 13(23):3832. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233832

Chicago/Turabian StyleHermosillo-Reynoso, Fernando, Juan-Carlos López-Pimentel, Erica Ruiz-Ibarra, Armando García-Berumen, José A. Del-Puerto-Flores, H. E. Gilardi-Velazquez, Vinoth Babu Kumaravelu, and L. A. Luna-Rodriguez. 2025. "A Transformer-Based Multi-Task Learning Model for Vehicle Traffic Surveillance" Mathematics 13, no. 23: 3832. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233832

APA StyleHermosillo-Reynoso, F., López-Pimentel, J.-C., Ruiz-Ibarra, E., García-Berumen, A., Del-Puerto-Flores, J. A., Gilardi-Velazquez, H. E., Kumaravelu, V. B., & Luna-Rodriguez, L. A. (2025). A Transformer-Based Multi-Task Learning Model for Vehicle Traffic Surveillance. Mathematics, 13(23), 3832. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233832