Tool-Life Estimation Model in Milling Processes Using Multi-Head Cross-Covariance Attention Fusion-Based Dilated Dense Bi-Directional Gated Recurrent Unit

Abstract

1. Introduction

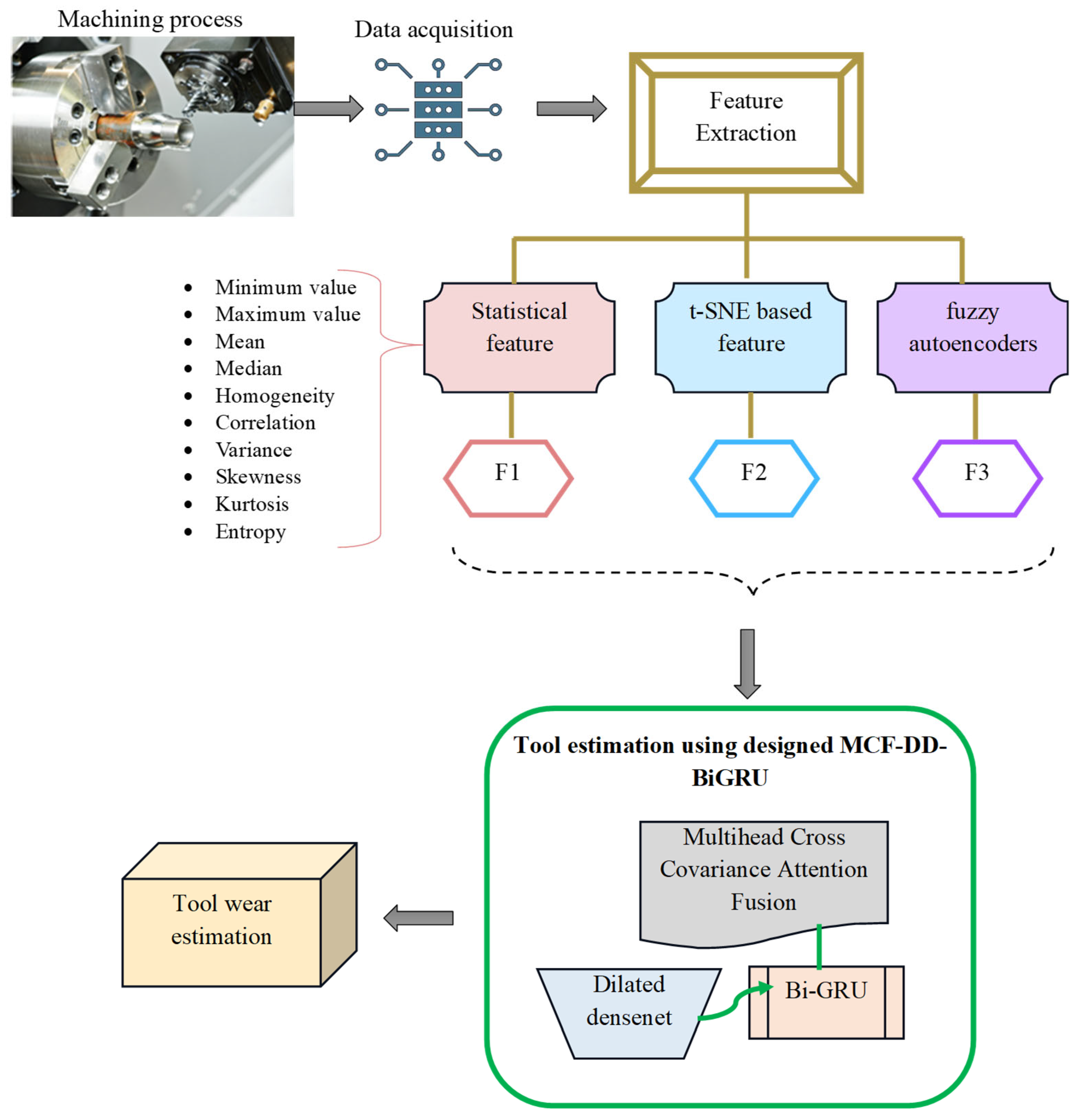

- To implement an intelligent tool-life estimation framework in the milling process by training efficient deep learning technology to predict the tool wear. This framework leverages multi-domain feature extraction to extract significant features, thereby achieving higher prediction accuracy. This prediction provides the status of RUL or tools’ current wear to perform proper tool changes at the right time. This tends to improve the machining precision and reduce the unplanned downtime in an intelligent manufacturing system with real-time monitoring.

- To convert the raw data into meaningful input features, this work performed the multi-domain feature extraction process for accurate tool-life prediction. The feature extraction utilizes statistical, t-SNE, and FAE to refine the information available for the model. This process effectively generates clear visual clusters of data points from the given data. This process automatically captures the relevant and comprehensive information from complex data for achieving better predictive maintenance.

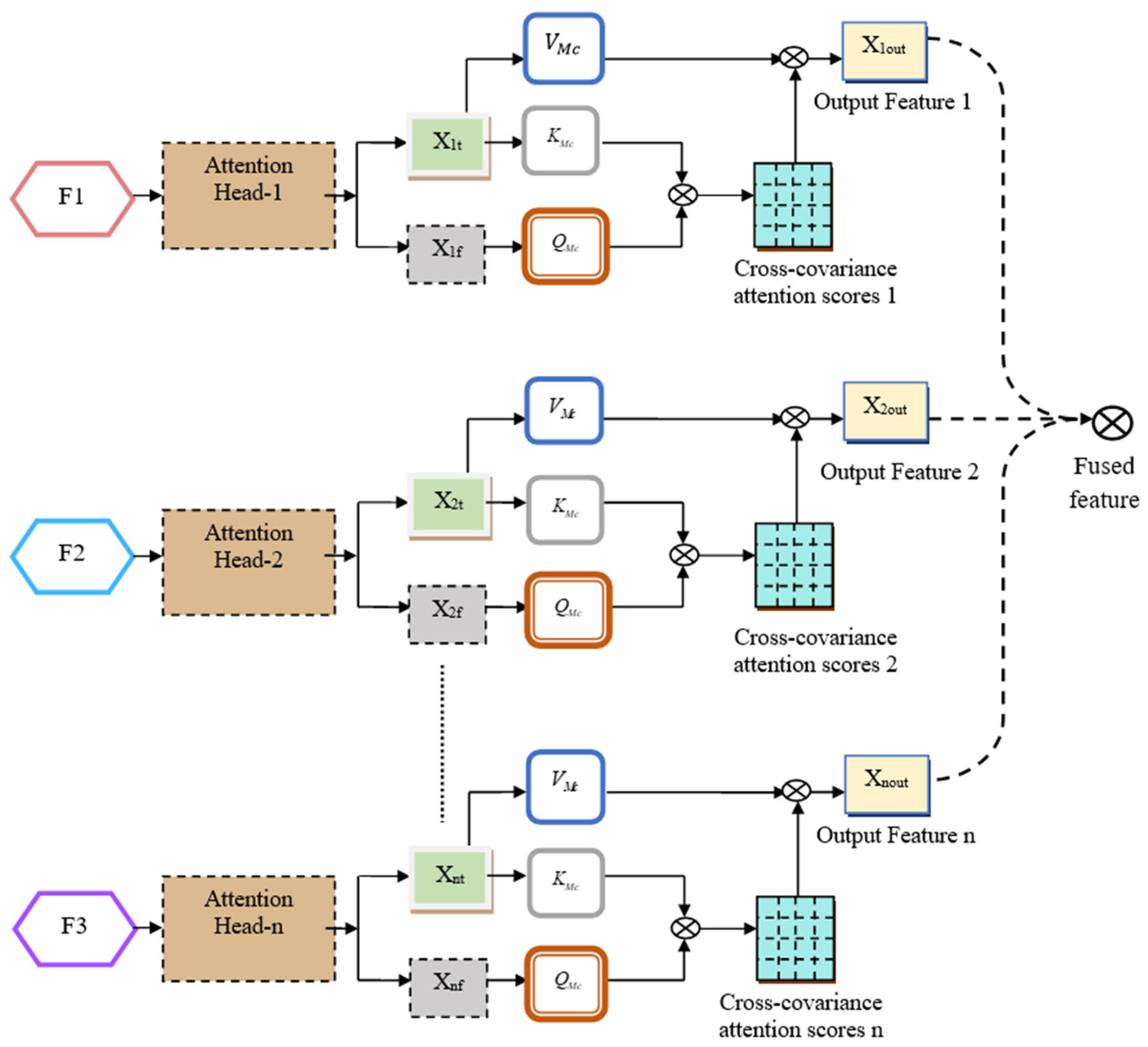

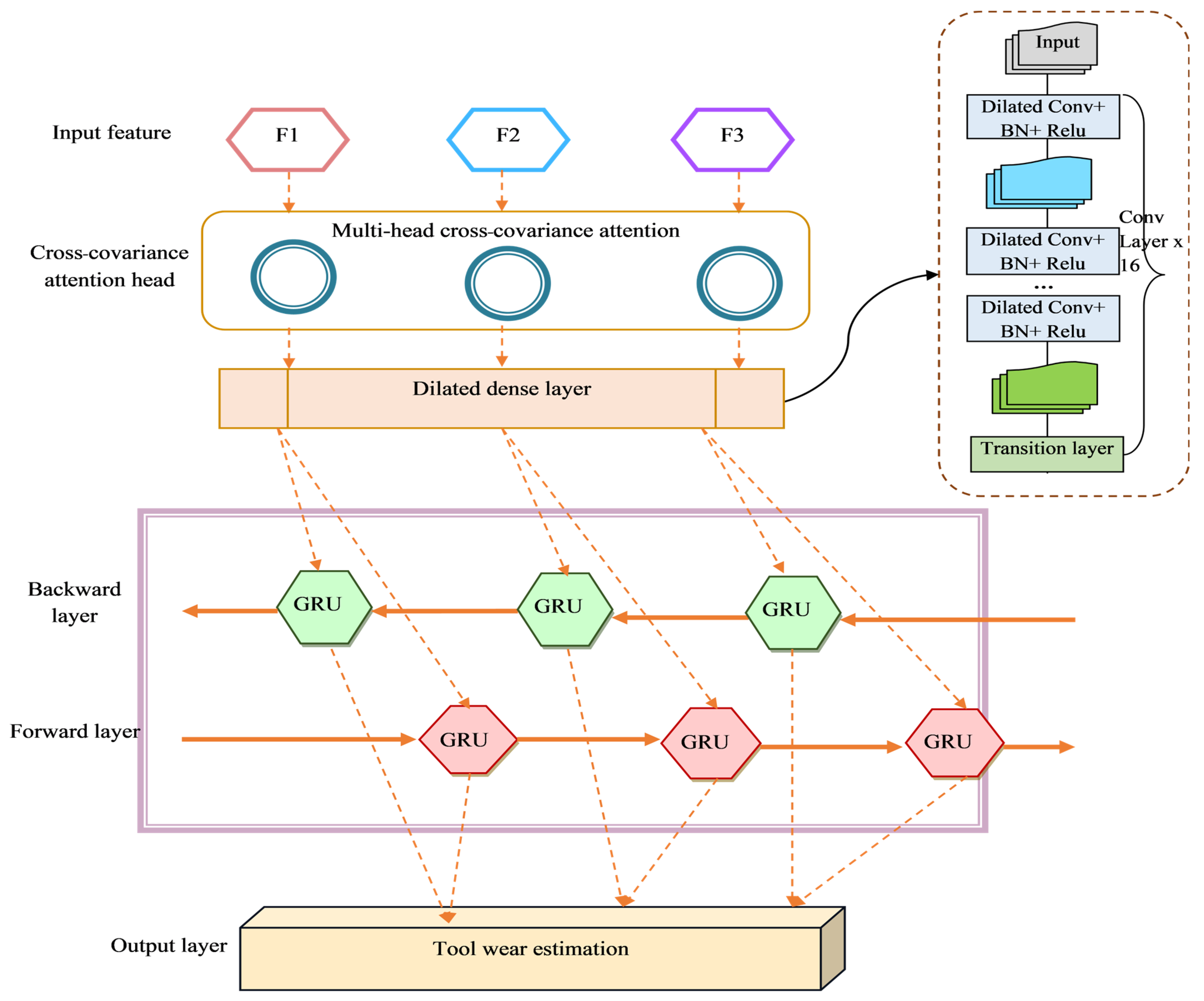

- To develop an MCF-DD-BiGRU for tool-life estimation with multi-head feature fusion. The system utilizes the MCF as the feature learner to determine the given three sets of features completely. Further, the DD-BiGRU performs the estimation based on the fused feature and delivers the present tool value. The model led to higher prediction accuracy, which is suitable for tool condition monitoring. Based on the outcome, the tool wear value can be monitored in real-time and make an intelligent decision to improve the processing quality of the product with a minimum rejection rate.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Related Works

2.2. Research Gaps and Challenges

- Existing approaches, such as SVM or CNN, are not feasible for capturing the complex and non-linear relationships in the sensor data collected during the milling process. Moreover, they are less efficient in analyzing unstructured feature spaces and high-dimensional data.

- Most of the models have obtained less prediction accuracy due to the loss of necessary information. Existing models cause this, as they only consider single-feature modalities.

- Issues such as inter-feature correlations and suboptimal utilization of diverse data sources may occur in conventional models, as they do not incorporate efficient feature fusion mechanisms.

- The computational complexity and memory consumption of the LSTM model are high. Both past and future signal patterns associated with tool wear are not precisely captured by the existing techniques.

3. Significance and Overview of the Proposed Tool-Life Estimation Process in Milling

3.1. Significance of Estimating the Tool Life in Milling

- Maximum utilization of the tool is allowed by understanding the remaining useful life of RUL, which also minimizes the cost related to premature regrinding or replacement. In addition, the higher production cost due to unforeseen tool failure is avoided.

- In general, poor surface finishes are achieved by the tool wear, which impacts the suitability and quality of the manufactured part. Hence, to rectify the issue, it is crucial to perform the tool-life estimation.

- The scheduled tool changes allowed by this tool-life estimation help avoid interruptions in the production process. Moreover, the selection of optimal settings is achieved by understanding machining parameters to balance productivity.

- While developing the automated processes and advanced manufacturing system, it is important to have tool-life estimation for continuous adjustment and monitoring.

- Forecasting the tool wear allows the manufacturer to gain knowledge about when the tool becomes unusable. This ensures better procurement and inventory management. In addition, it also improves the process control for a reliable outcome.

- Precision and machining accuracy greatly affect the final product when using the worn tool, resulting in a loss. This results in a semi-finished product and the wasting of expensive materials.

3.2. Proposed Estimation Model and Its Details

3.3. Experimented Dataset Details

4. Different Set of Feature Engineering Mechanisms for Determining the Tool Life

4.1. Statistical Features

4.2. T-SNE Features

4.3. Fuzzy Autoencoder

5. Calculation of Milling Tool Life Using Multi-Head Cross-Attention for Fusion with Dilated Dense Bi-GRU

5.1. Multi-Head Cross-Covariance Attention Fusion

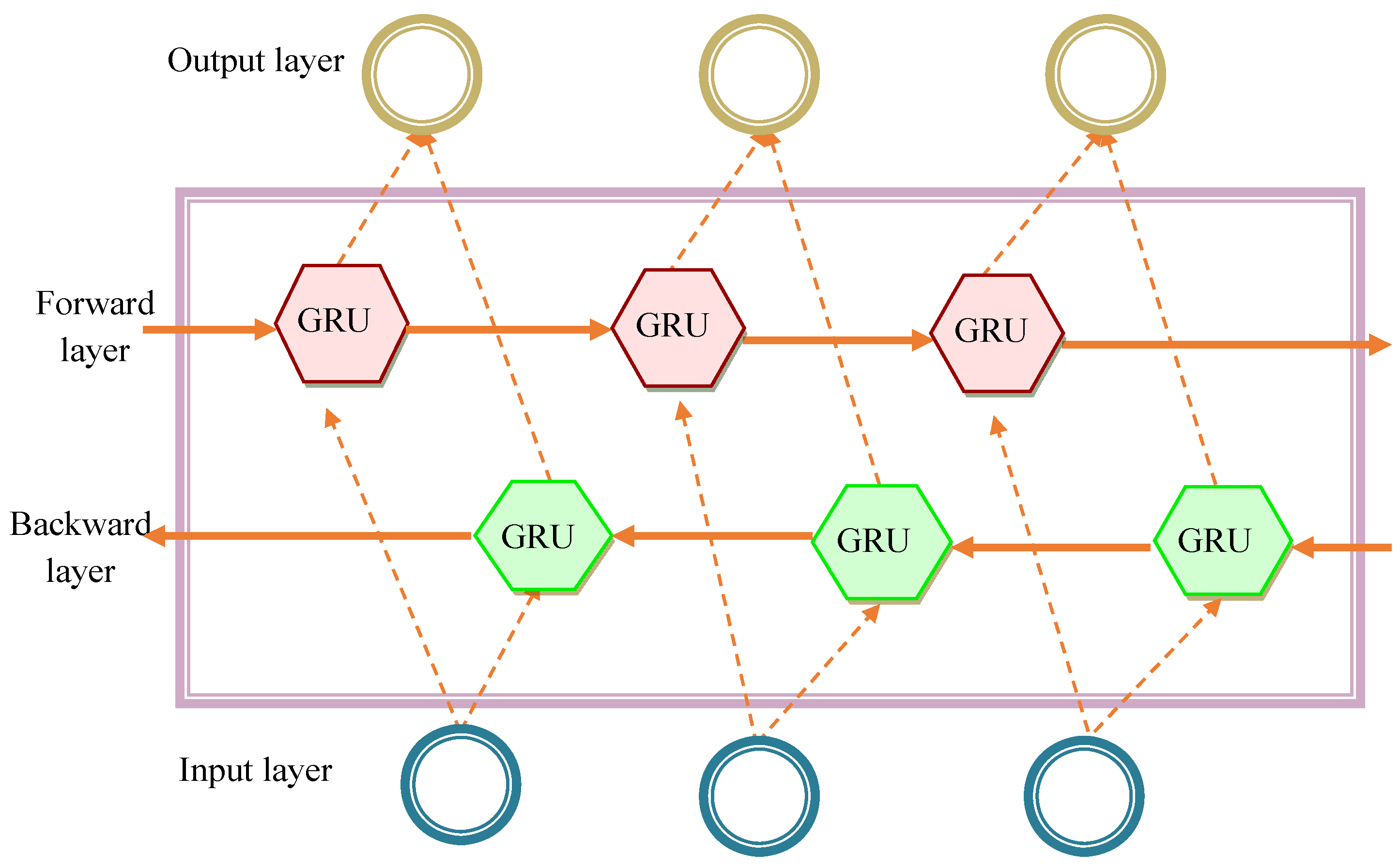

5.2. Bi-GRU

5.3. Proposed MCF-DD-BiGRU for Estimation

6. Results and Discussion

6.1. Experimental Setup

6.2. Evaluation Metrics

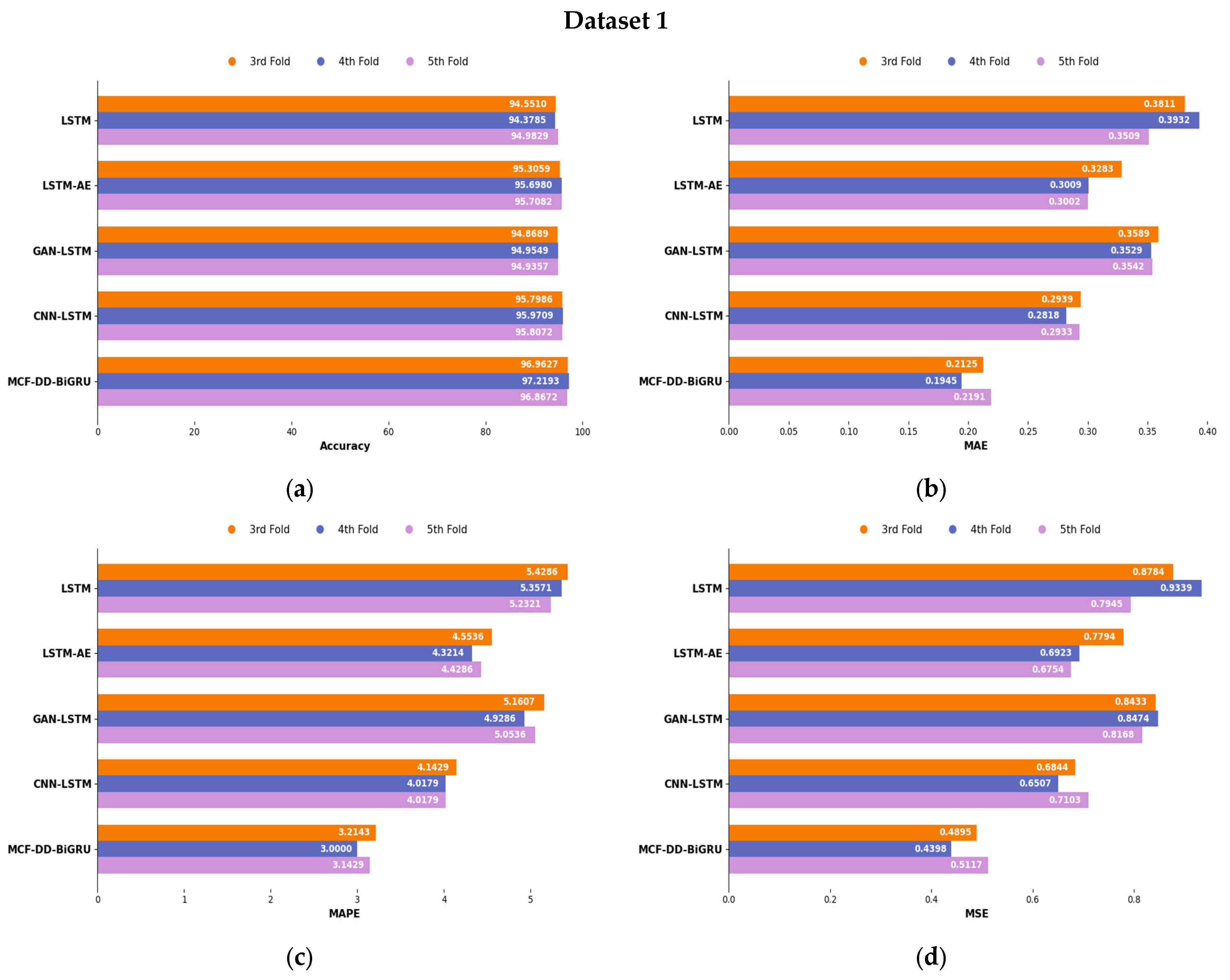

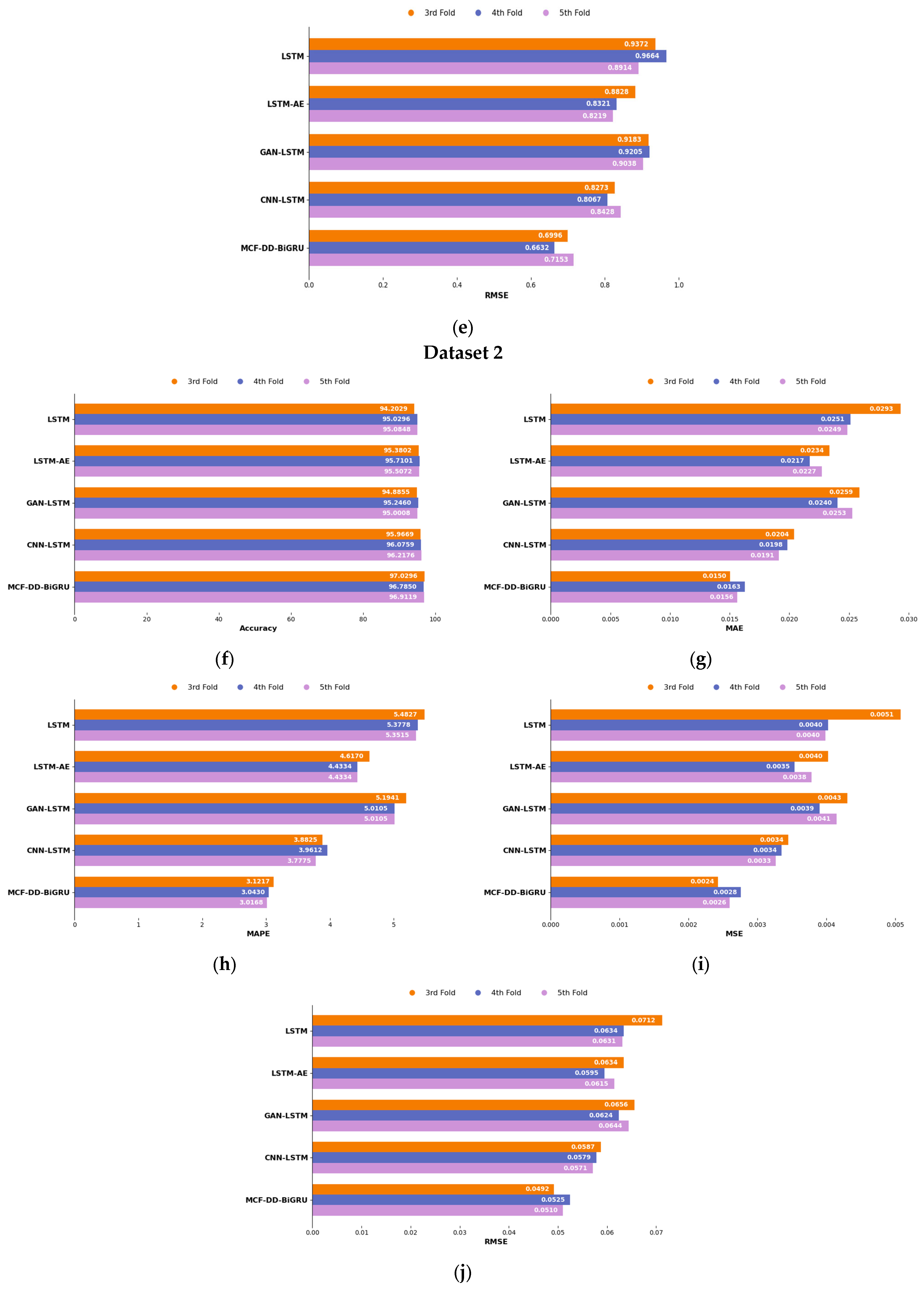

6.3. K-Fold-Based Performance Analysis of MCF-DD-BiGRU for Tool-Life Estimation

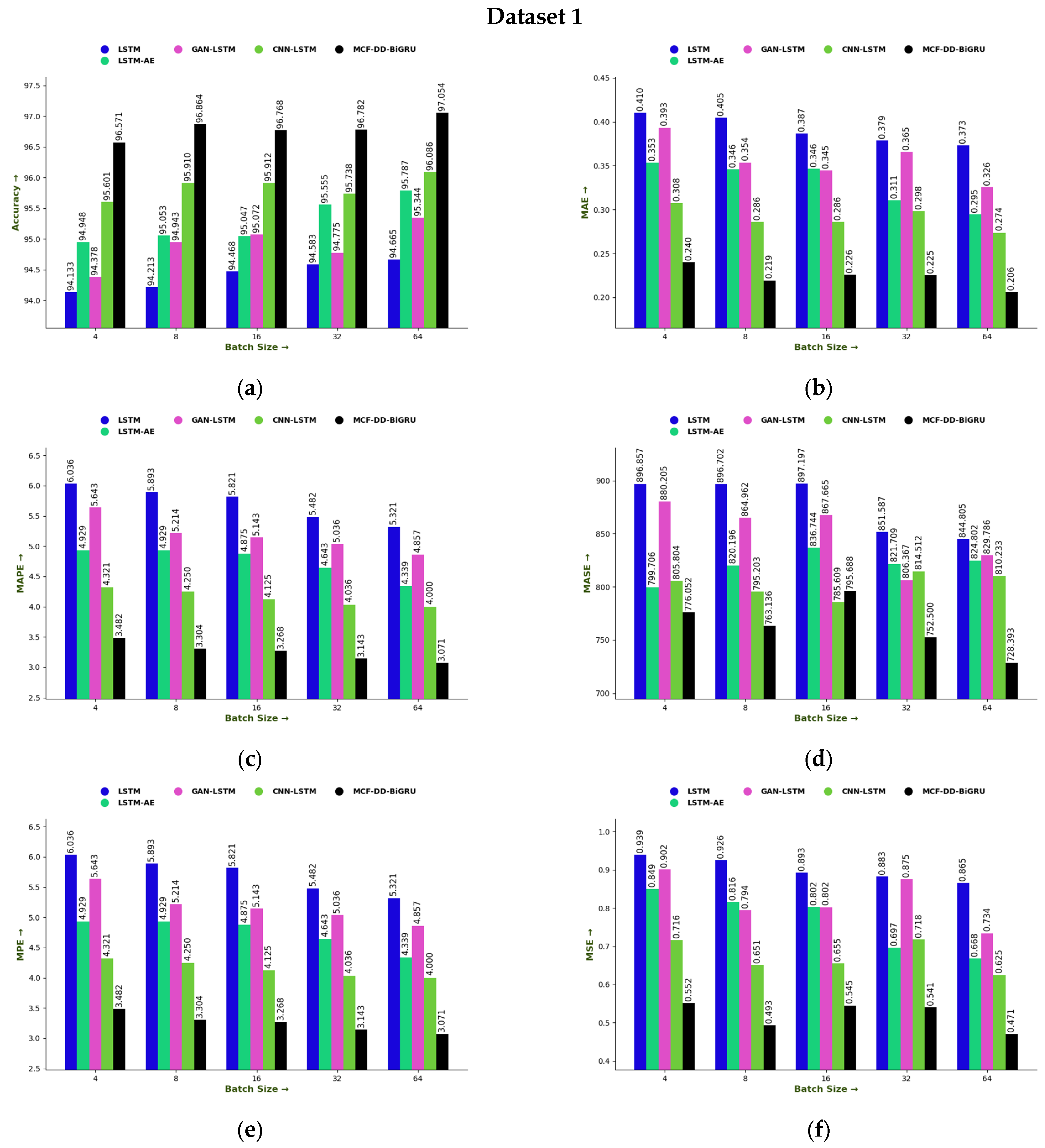

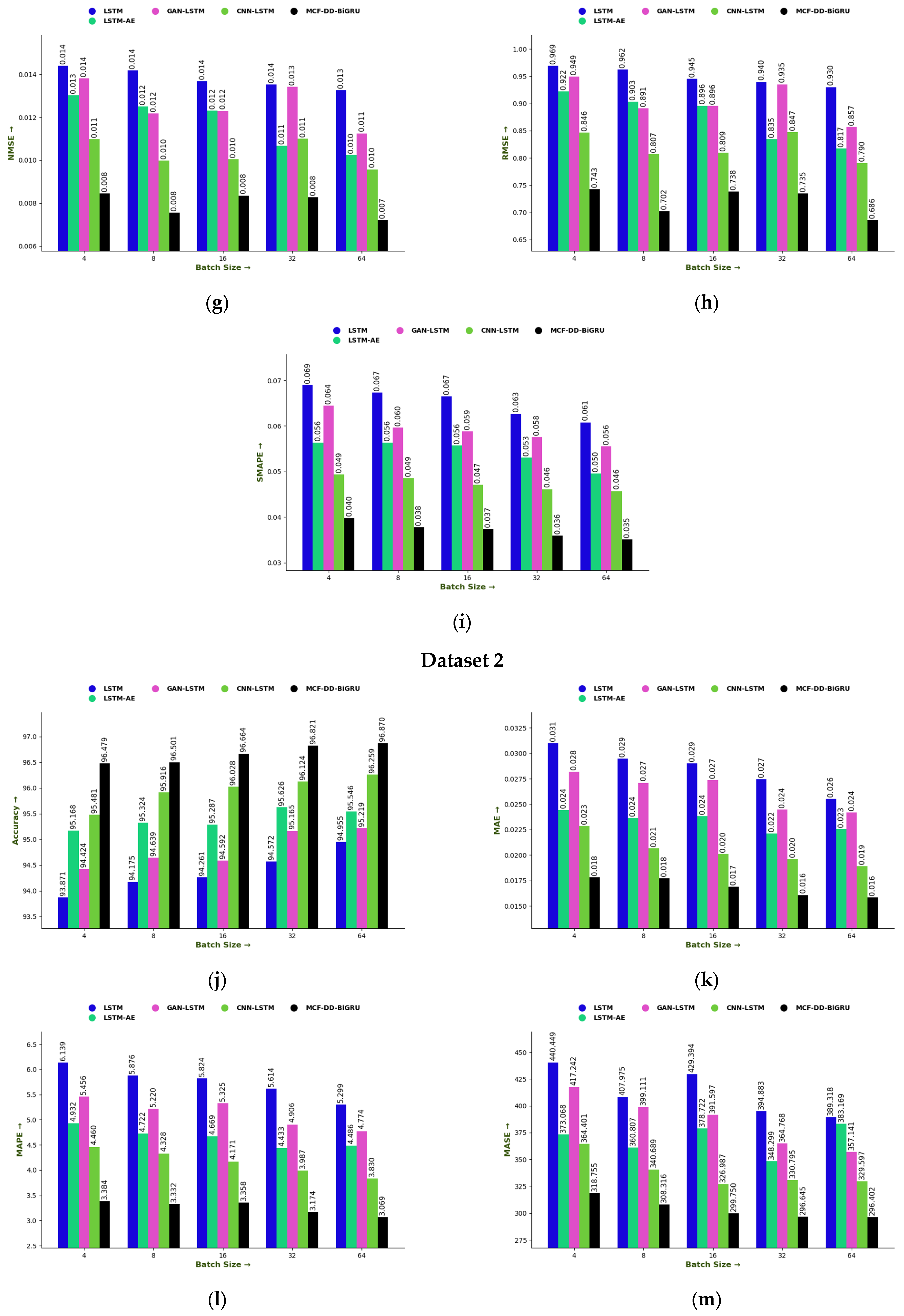

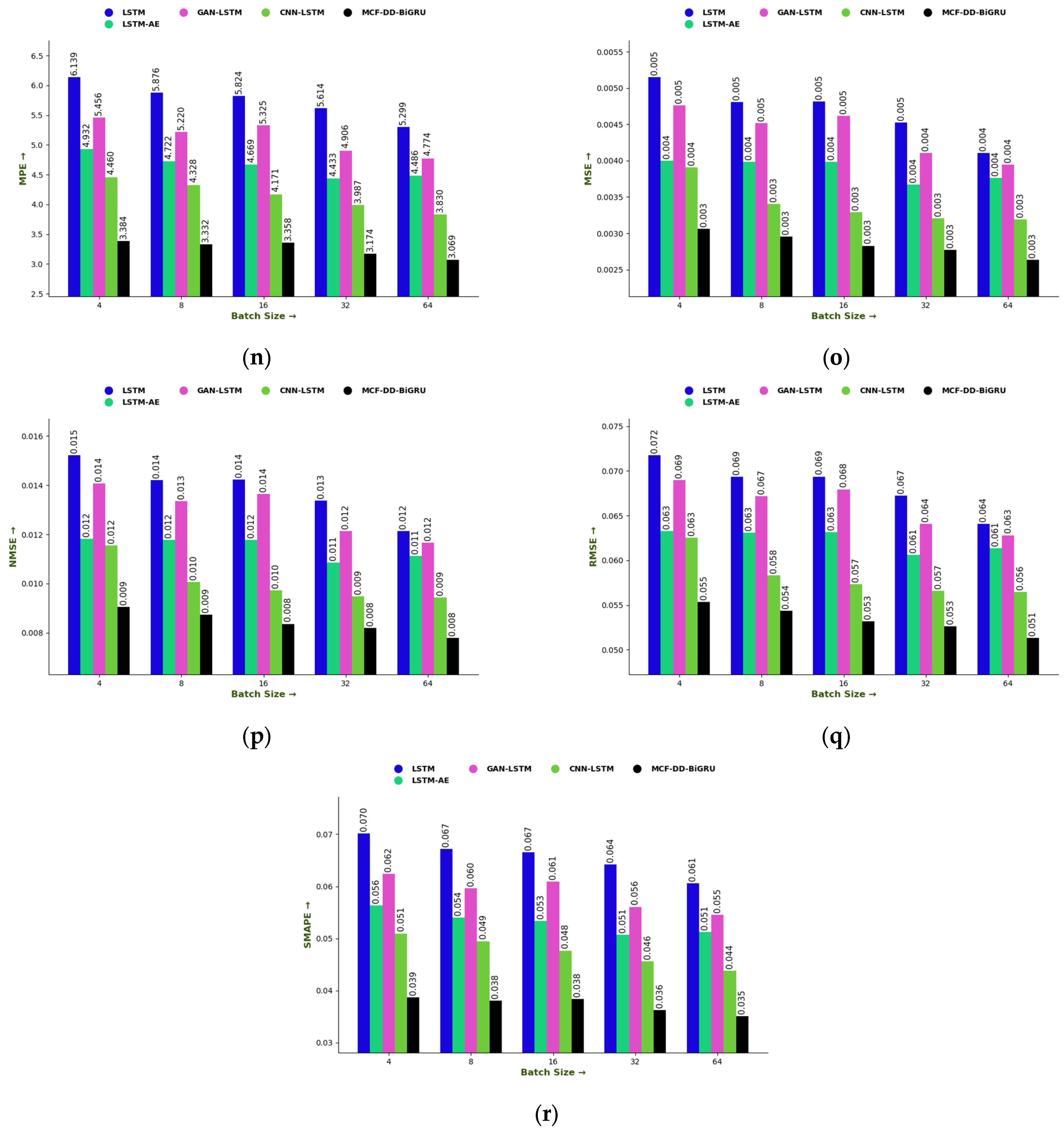

6.4. Performance Assessment of MCF-DD-BiGRU Based on Batch Size

6.5. Epoch-Based Comparative Analysis for Designed MCF-DD-BiGRU

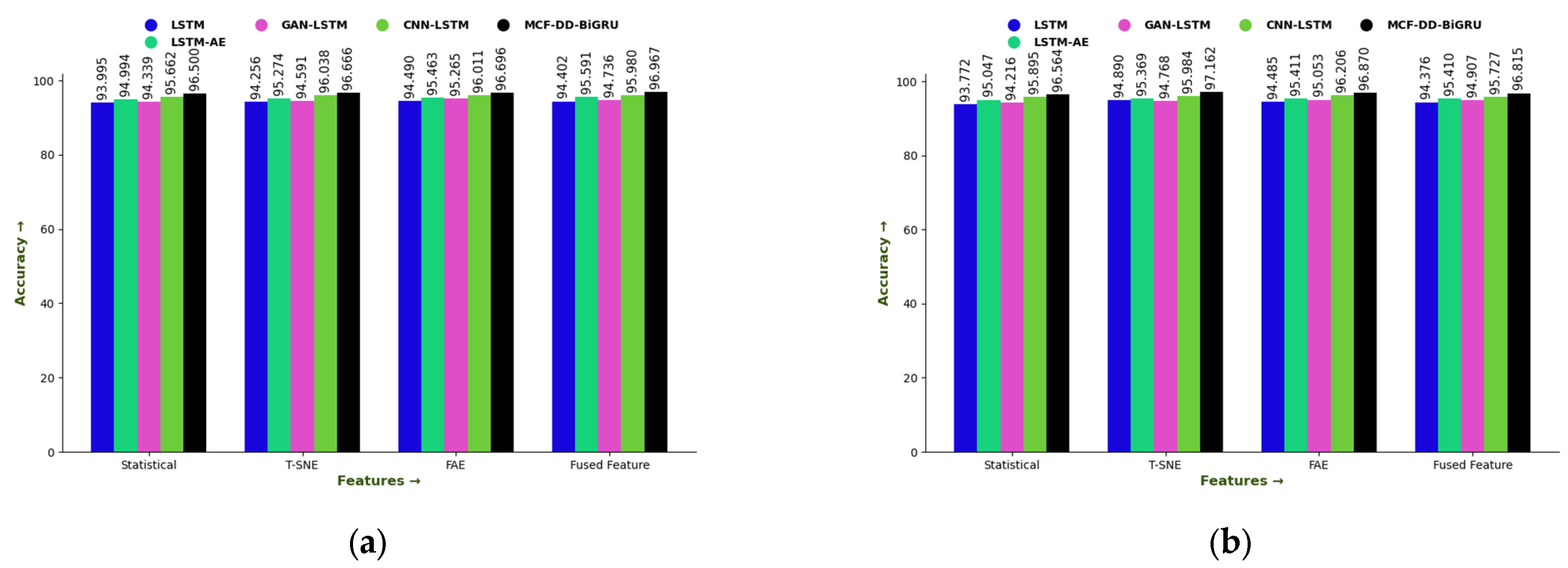

6.6. Contributions of Features in Designed MCF-DD-BiGRU

6.7. Ablation Study

6.8. Computational Complexity Analysis

6.9. Impact of Modifications to Key Parameters on Results

7. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| t-SNE | t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding |

| MCF-DD-BiGRU | Multi-head cross-covariance attention fusion-based dilated dense bi-directional gated recurrent unit |

| FAE | Fuzzy autoencoder |

| RUL | Remaining useful life |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine learning |

| DBN | Dynamic Bayesian Network |

| MCF | Multi-head cross-covariance attention fusion |

| Bi-GRU | bi-directional gated recurrent unit |

| DD | Dilated dense |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbor |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CCA | Cross-Covariance Attention |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

| MAPE | Mean absolute percentage error |

| MSE | Mean squared error |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| MASE | Mean absolute scaled error |

| MPE | Mean percentage error |

| SMAPE | Symmetric mean absolute percentage error |

| KL | Kullback–Leibler divergence |

References

- Wang, X.; Yan, J. Deep learning based multi-source heterogeneous information fusion framework for online monitoring of surface quality in milling process. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Tian, W. A novel simultaneous monitoring method for surface roughness and tool wear in milling process. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hojati, F.; Azarhoushang, B.; Daneshi, A.; Hajyaghaee Khiabani, R. Prediction of Machining Condition Using Time Series Imaging and Deep Learning in Slot Milling of Titanium Alloy. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2022, 6, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Kamal, K.; Ratlamwala, T.A.H.; Hussain, G.; Alqahtani, M.; Alkahtani, M.; Alatefi, M.; Alzabidi, A. Tool Health Monitoring of a Milling Process Using Acoustic Emissions and a ResNet Deep Learning Model. Sensors 2023, 23, 3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, B.; Park, G. Non-contact surface roughness evaluation of milling surface using CNN-deep learning models. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2024, 37, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, M.; Siddique, M.F.; Ullah, N.; Kim, J.-M. Milling Machine Fault Diagnosis Using Acoustic Emission and Hybrid Deep Learning with Feature Optimization. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabacak, Y.E. Deep learning-based CNC milling tool wear stage estimation with multi-signal analysis. Eksploat. I Niezawodn. Maint. Reliab. 2023, 25, 168082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhani, G.; Kurukuri, S.; Myers, R.; Santos, N.; Tauhiduzzaman, M. Unlocking Dual Utility: 1D-CNN for Milling Tool Health Assessment and Experimental Optimization. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 105096–105107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, S.; Li, Q.; Zhong, S.; Chen, B. Remaining Useful Life Prediction of Milling Tool Based on Pyramid CNN. Shock Vib. 2023, 2023, 1830694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyad, S.; Kumar, S.; Bongale, A.; Kotecha, K.; Abraham, A. Remaining Useful-Life Prediction of the Milling Cutting Tool Using Time–Frequency-Based Features and Deep Learning Models. Sensors 2023, 23, 5659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Zhang, J.; Bu, L.; Nie, S.; Bai, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Mei, N. Methodology and Experimental Verification for Predicting the Remaining Useful Life of Milling Cutters Based on Hybrid CNN-LSTM-Attention-PSA. Machines 2024, 12, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidi, M.H.; Alkhalefah, H.; Umer, U. Fuzzy harmony search based optimal control strategy for wireless cyber physical system with industry 4.0. J. Intell. Manuf. 2022, 33, 1795–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidi, M.H.; Alkhalefah, H.; Umer, U.; Mohammed, M.K. Blockchain-based secure information sharing for supply chain management: Optimization assisted data sanitization process. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2021, 36, 260–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidi, M.H. Multimodal data-based human motion intention prediction using adaptive hybrid deep learning network for movement challenged person. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cen, Z.; Hu, S.; Hou, Y.; Chen, Z.; Ke, Y. Remaining useful life prediction of machinery based on improved Sample Convolution and Interaction Network. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 135, 108813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidi, M.H.; Mohammed, M.K.; Alkhalefah, H. Predictive Maintenance Planning for Industry 4.0 Using Machine Learning for Sustainable Manufacturing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, M.; Gupta, M.K.; Irfan, S.A.; Ghazali, S.M.; Rathore, M.F.; Krolczyk, G.M.; Alsaady, A. Machine learning models for prediction and classification of tool wear in sustainable milling of additively manufactured 316 stainless steel. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 102015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omole, S.; Dogan, H.; Lunt, A.J.G.; Kirk, S.; Shokrani, A. Using machine learning for cutting tool condition monitoring and prediction during machining of tungsten. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2024, 37, 747–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Kamal, K.; Ratlamwala, T.A.H.; Alkahtani, M.; Almatani, M.; Mathavan, S. Tool Health Classification in Metallic Milling Process Using Acoustic Emission and Long Short-Term Memory Networks: A Deep Learning Approach. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 126611–126633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elminir, H.K.; El-Brawany, M.A.; Ibrahim, D.A.; Elattar, H.M.; Ramadan, E.A. An efficient deep learning prognostic model for remaining useful life estimation of high speed CNC milling machine cutters. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Z.; Peng, C.; Liao, T.W.; Wang, J. Improving milling tool wear prediction through a hybrid NCA-SMA-GRU deep learning model. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 255, 124556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Vakharia, V.; Chaudhari, R.; Vora, J.; Pimenov, D.Y.; Giasin, K. Tool wear prediction in face milling of stainless steel using singular generative adversarial network and LSTM deep learning models. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 121, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yu, Z.; Xu, G.; Zhao, F. Research on Tool Remaining Life Prediction Method Based on CNN-LSTM-PSO. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 80448–80464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamat, P.; Kumar, S.; Kotecha, K. DeepTool: A deep learning framework for tool wear onset detection and remaining useful life prediction. MethodsX 2024, 13, 102965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Liu, X.; Yue, C.; Wang, L.; Liang, S.Y. Data-model linkage prediction of tool remaining useful life based on deep feature fusion and Wiener process. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 73, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliyannan, D.; Thangamuthu, M.; Pradeep, P.; Gnansekaran, S.; Rakkiyannan, J.; Pramanik, A. Tool Condition Monitoring in the Milling Process Using Deep Learning and Reinforcement Learning. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2024, 13, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milling Tool Wear and RUL Dataset; Kaggle: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/programmer3/milling-tool-wear-and-rul-dataset (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Piecuch, G.; Żabiński, T. A new open dataset from a milling process—Data for classification and estimation of tool life. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanimozhi, M.; Roselin, R. Statistical Feature Extraction and Classification using Machine Learning Techniques in Brain-Computer Interface. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 2020, 9, 1754–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalayah, K.M.; Senan, E.M.; Atlam, H.F.; Ahmed, I.A.; Shatnawi, H.S.A. Effective Early Detection of Epileptic Seizures through EEG Signals Using Classification Algorithms Based on t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding and K-Means. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, T. Self-supervised Discriminative Representation Learning by Fuzzy Autoencoder. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2022, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voita, E.; Talbot, D.; Moiseev, F.; Sennrich, R.; Titov, I. Analyzing Multi-Head Self-Attention: Specialized Heads Do the Heavy Lifting, the Rest Can Be Pruned. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Florence, Italy, 28 July–2 August 2019; pp. 5797–5808. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, M.M.K.; Singh, V.K.; Alsharid, M.; Hernandez-Cruz, N.; Papageorghiou, A.T.; Noble, J.A. COMFormer: Classification of Maternal-Fetal and Brain Anatomy Using a Residual Cross-Covariance Attention Guided Transformer in Ultrasound. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2023, 70, 1417–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, A.; Xu, X.; Li, P.; Ji, Y. Prediction of Particulate Concentration Based on Correlation Analysis and a Bi-GRU Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasulu, M.; Maiti, S. RNDDNet: A residual nested dilated DenseNet based deep-learning model for chilli plant disease classification. Eng. Res. Express 2024, 6, 035204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author [Citation] | Methodology | Features | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Khan et al. [19] | LSTM |

| Memory consumption is high. |

| Elminir et al. [20] | LSTM-AE |

| It considers redundant data, which leads to high processing time. The computational complexity of the model is high when dealing with long data sequences. |

| Che et al. [21] | NCA-SMA-GRU |

| The modeling time is high. |

| Shah et al. [22] | GAN and LSTM |

| Computationally expensive, and it has training instability issues. |

| Wang et al. [23] | CNN-LSTM-PSO |

| The training time of the model is high. |

| Kamat et al. [24] | DeepTool |

| It suffers from overfitting issues. |

| Li et al. [25] | CSBLSTM-TSAM |

| Predicting the lifetime of machines with curved parts is complex. The robustness of the model is affected by changing the parameters of the milling machine. |

| Kaliyannan et al. [26] | LSTM and FFNN |

| It is ineffective in capturing time-based patterns. |

| Hyperparameter | Searched Range/Defaults | Final Pick(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Learning Rate (LR) | 0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1 | 0.01 |

| Hidden Size (HN) | [64, 128, 256] | 128 |

| Number of Attention Heads | [4, 8, 16] | 4 |

| Dilation Rates | [1, 2, 3, 4] | 4 |

| Depth of Dense Blocks | [1, 2, 3] | 1 |

| Dropout Rate | [0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4] | 0.4 |

| Early Stopping | Patience: 10, Monitor: ‘val_loss’ | - |

| Epoch | LSTM [19] | LSTM-AE [20] | GAN-LSTM [22] | CNN-LSTM [23] | MCF-DD-BiGRU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset 1 | |||||

| MPE | |||||

| 10 | 6.125 | 4.964286 | 5.535714 | 4.446429 | 3.553571 |

| 20 | 5.946429 | 4.910714 | 5.375 | 4.25 | 3.267857 |

| 30 | 5.767857 | 4.625 | 5.089286 | 4.142857 | 3.196429 |

| 40 | 5.660714 | 4.5 | 5.053571 | 4.071429 | 3.160714 |

| 50 | 5.339286 | 4.482143 | 4.785714 | 3.964286 | 3.053571 |

| 60 | 5.267857 | 4.410714 | 4.821429 | 3.928571 | 3.107143 |

| SMAPE | |||||

| 10 | 7 | 5.673469 | 6.326531 | 5.081633 | 4.061224 |

| 20 | 6.795918 | 5.612245 | 6.142857 | 4.857143 | 3.734694 |

| 30 | 6.591837 | 5.285714 | 5.816327 | 4.734694 | 3.653061 |

| 40 | 6.469388 | 5.142857 | 5.77551 | 4.653061 | 3.612245 |

| 50 | 6.102041 | 5.122449 | 5.469388 | 4.530612 | 3.489796 |

| 60 | 6.020408 | 5.040816 | 5.510204 | 4.489796 | 3.55102 |

| RMSE | |||||

| 10 | 10.15868 | 9.336447 | 9.20071 | 8.728049 | 7.445795 |

| 20 | 9.839033 | 8.517013 | 9.440956 | 8.50815 | 7.509238 |

| 30 | 9.956536 | 8.595302 | 9.726698 | 8.399718 | 6.96534 |

| 40 | 9.622079 | 8.89281 | 9.053666 | 8.350308 | 7.148677 |

| 50 | 9.311087 | 8.314425 | 8.78561 | 7.559584 | 7.398947 |

| 60 | 9.612436 | 8.692587 | 9.057767 | 8.195201 | 7.015632 |

| MASE | |||||

| 10 | 946.7651 | 855.762 | 862.3747 | 799.7338 | 777.4966 |

| 20 | 896.9576 | 816.0386 | 900.5572 | 806.3521 | 764.6227 |

| 30 | 862.6906 | 851.9967 | 862.5689 | 821.9569 | 773.2036 |

| 40 | 926.3732 | 823.3261 | 833.5765 | 794.319 | 784.6413 |

| 50 | 847.9551 | 793.5111 | 839.9428 | 753.1057 | 761.0283 |

| 60 | 905.8937 | 813.4717 | 848.5818 | 817.0405 | 728.18 |

| MAE | |||||

| 10 | 4.335371 | 3.630108 | 3.732796 | 3.218234 | 2.466241 |

| 20 | 4.143531 | 3.278485 | 3.78853 | 3.09333 | 2.388016 |

| 30 | 4.224391 | 3.211893 | 3.803556 | 2.983011 | 2.105449 |

| 40 | 3.981789 | 3.275068 | 3.524696 | 2.942779 | 2.210008 |

| 50 | 3.714829 | 2.990979 | 3.312419 | 2.542821 | 2.249609 |

| 60 | 3.80338 | 3.174758 | 3.440739 | 2.809722 | 2.114432 |

| MSE | |||||

| 10 | 10.31987 | 8.716924 | 8.465306 | 7.617883 | 5.543986 |

| 20 | 9.680657 | 7.253952 | 8.913166 | 7.238862 | 5.638866 |

| 30 | 9.913261 | 7.387922 | 9.460865 | 7.055527 | 4.851596 |

| 40 | 9.258441 | 7.908207 | 8.196887 | 6.972764 | 5.110358 |

| 50 | 8.669635 | 6.912967 | 7.718695 | 5.71473 | 5.474442 |

| 60 | 9.239892 | 7.556106 | 8.204314 | 6.716132 | 4.921909 |

| NMSE | |||||

| 10 | 1.581359 | 1.335732 | 1.297176 | 1.167322 | 0.849529 |

| 20 | 1.48341 | 1.111555 | 1.365803 | 1.109243 | 0.864068 |

| 30 | 1.519053 | 1.132084 | 1.44973 | 1.081149 | 0.743431 |

| 40 | 1.418712 | 1.211809 | 1.256045 | 1.068467 | 0.783083 |

| 50 | 1.328486 | 1.059304 | 1.182769 | 0.875693 | 0.838873 |

| 60 | 1.415869 | 1.157855 | 1.257183 | 1.029142 | 0.754206 |

| Accuracy | |||||

| 10 | 93.80197 | 94.81018 | 94.66337 | 95.3991 | 96.47411 |

| 20 | 94.07615 | 95.31295 | 94.58369 | 95.57759 | 96.58595 |

| 30 | 93.96064 | 95.40815 | 94.5622 | 95.7353 | 96.98992 |

| 40 | 94.30746 | 95.31776 | 94.96095 | 95.79282 | 96.84044 |

| 50 | 94.68905 | 95.72391 | 95.26436 | 96.36463 | 96.78382 |

| 60 | 94.56253 | 95.46126 | 95.08091 | 95.98305 | 96.97708 |

| Dataset 2 | |||||

| MPE | |||||

| 10 | 6.374607 | 4.80063 | 5.69255 | 4.223505 | 3.462749 |

| 20 | 5.954879 | 4.80063 | 5.403987 | 4.354669 | 3.331584 |

| 30 | 5.849948 | 4.748164 | 5.062959 | 4.013641 | 3.147954 |

| 40 | 5.797482 | 4.643232 | 4.879328 | 3.83001 | 3.279119 |

| 50 | 5.377754 | 4.459601 | 4.669465 | 3.934942 | 3.043022 |

| 60 | 5.272823 | 4.302204 | 4.80063 | 3.856243 | 3.016789 |

| SMAPE | |||||

| 10 | 7.285265 | 5.486434 | 6.505771 | 4.826863 | 3.957428 |

| 20 | 6.805576 | 5.486434 | 6.175986 | 4.976765 | 3.807525 |

| 30 | 6.685654 | 5.426473 | 5.786239 | 4.587018 | 3.597662 |

| 40 | 6.625693 | 5.306551 | 5.576375 | 4.377155 | 3.747564 |

| 50 | 6.146005 | 5.096687 | 5.336531 | 4.497077 | 3.477739 |

| 60 | 6.026083 | 4.916804 | 5.486434 | 4.407135 | 3.447759 |

| RMSE | |||||

| 10 | 7.431344 | 6.643252 | 6.885293 | 5.778184 | 5.069942 |

| 20 | 6.888637 | 6.482618 | 6.799102 | 6.142759 | 5.406138 |

| 30 | 7.038907 | 6.496948 | 6.359537 | 5.739587 | 5.232892 |

| 40 | 7.207774 | 6.395633 | 6.332227 | 5.382166 | 5.42488 |

| 50 | 7.078538 | 6.345149 | 6.112087 | 5.724741 | 5.02194 |

| 60 | 6.733888 | 6.119597 | 6.361739 | 5.760822 | 5.054418 |

| MASE | |||||

| 10 | 449.2075 | 382.5456 | 424.1658 | 330.4695 | 291.034 |

| 20 | 420.022 | 380.3023 | 395.9337 | 359.679 | 301.1804 |

| 30 | 410.6396 | 382.0612 | 381.0258 | 327.0288 | 292.1369 |

| 40 | 421.7488 | 380.1668 | 378.3147 | 301.1708 | 311.6336 |

| 50 | 410.4199 | 364.2985 | 370.3846 | 325.5384 | 276.8786 |

| 60 | 398.2375 | 358.1721 | 375.7199 | 333.3341 | 282.7617 |

| MAE | |||||

| 10 | 3.277164 | 2.535518 | 2.88323 | 2.055218 | 1.606044 |

| 20 | 2.919401 | 2.45275 | 2.749124 | 2.208157 | 1.709625 |

| 30 | 2.973501 | 2.487324 | 2.463018 | 1.97411 | 1.636935 |

| 40 | 3.065401 | 2.422543 | 2.407664 | 1.785126 | 1.687677 |

| 50 | 2.879411 | 2.341971 | 2.300087 | 1.987604 | 1.546472 |

| 60 | 2.69769 | 2.230625 | 2.390433 | 1.978993 | 1.538482 |

| MSE | |||||

| 10 | 0.552249 | 0.441328 | 0.474073 | 0.333874 | 0.257043 |

| 20 | 0.474533 | 0.420243 | 0.462278 | 0.377335 | 0.292263 |

| 30 | 0.495462 | 0.422103 | 0.404437 | 0.329429 | 0.273832 |

| 40 | 0.51952 | 0.409041 | 0.400971 | 0.289677 | 0.294293 |

| 50 | 0.501057 | 0.402609 | 0.373576 | 0.327727 | 0.252199 |

| 60 | 0.453452 | 0.374495 | 0.404717 | 0.331871 | 0.255471 |

| NMSE | |||||

| 10 | 1.632492 | 1.304601 | 1.401397 | 0.986959 | 0.75984 |

| 20 | 1.402759 | 1.242274 | 1.366531 | 1.115433 | 0.863954 |

| 30 | 1.464627 | 1.247772 | 1.195549 | 0.973818 | 0.809468 |

| 40 | 1.535743 | 1.209159 | 1.185303 | 0.856309 | 0.869955 |

| 50 | 1.481165 | 1.190146 | 1.104321 | 0.968786 | 0.74552 |

| 60 | 1.340442 | 1.107037 | 1.196377 | 0.981037 | 0.755194 |

| Accuracy | |||||

| 10 | 93.52122 | 94.98741 | 94.3 | 95.93694 | 96.82494 |

| 20 | 94.22849 | 95.15104 | 94.56513 | 95.63459 | 96.62016 |

| 30 | 94.12154 | 95.08269 | 95.13074 | 96.09729 | 96.76386 |

| 40 | 93.93986 | 95.21076 | 95.24017 | 96.4709 | 96.66355 |

| 50 | 94.30755 | 95.37004 | 95.45285 | 96.07061 | 96.94271 |

| 60 | 94.66681 | 95.59017 | 95.27424 | 96.08763 | 96.9585 |

| Terms | GRU | Bi-GRU | Dilated Bi-GRU | Dense Bi-GRU | Dilated DenseBi-GRU | MCF-DD-BiGRU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset 1 | ||||||

| Accuracy (%) | 95.83 | 96.06 | 96.23 | 96.11 | 96.19 | 96.52 |

| Dataset 2 | ||||||

| Accuracy (%) | 95.79 | 95.96 | 95.8 | 96.33 | 96.43 | 96.49 |

| Terms | LSTM-AE [19] | NCA-SMA-GRU [19] | CNN-LSTM-PSO [19] | CSBLSTM-TSAM [19] | MCF-DD-BiGRU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset 1 | |||||

| Training Time | 43.64649961 | 42.29822822 | 41.47202515 | 40.18363694 | 35.28433801 |

| Testing Time | 11.86451866 | 11.91198138 | 11.49771959 | 11.41539469 | 10.5320641 |

| Computational Time | 55.51101827 | 54.2102096 | 52.96974474 | 51.59903163 | 45.81640211 |

| Computational Space | 224 | 226 | 216 | 205 | 205 |

| Dataset 2 | |||||

| Training Time | 41.36714968 | 42.06272651 | 39.28451891 | 38.60131932 | 37.6526821 |

| Testing Time | 11.51236742 | 11.50162516 | 11.44002281 | 10.90986397 | 10.0094979 |

| Computational Time | 52.87951711 | 53.56435167 | 50.72454172 | 49.51118329 | 47.66218 |

| Computational Space | 209 | 211 | 205 | 202 | 200 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alkhalefah, H. Tool-Life Estimation Model in Milling Processes Using Multi-Head Cross-Covariance Attention Fusion-Based Dilated Dense Bi-Directional Gated Recurrent Unit. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3798. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233798

Alkhalefah H. Tool-Life Estimation Model in Milling Processes Using Multi-Head Cross-Covariance Attention Fusion-Based Dilated Dense Bi-Directional Gated Recurrent Unit. Mathematics. 2025; 13(23):3798. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233798

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlkhalefah, Hisham. 2025. "Tool-Life Estimation Model in Milling Processes Using Multi-Head Cross-Covariance Attention Fusion-Based Dilated Dense Bi-Directional Gated Recurrent Unit" Mathematics 13, no. 23: 3798. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233798

APA StyleAlkhalefah, H. (2025). Tool-Life Estimation Model in Milling Processes Using Multi-Head Cross-Covariance Attention Fusion-Based Dilated Dense Bi-Directional Gated Recurrent Unit. Mathematics, 13(23), 3798. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233798