1. Introduction

Complex dynamical networks (CDNs) have attracted extensive research attention in recent years due to their widespread applications in fields such as power systems, water and gas distribution systems, and transportation systems. Typically, a CDN is composed of a large number of nodes (or agents and subsystems) that interact with each other across both physical and cyber layers in such a way as to achieve some cooperative dynamical behaviors. Not surprisingly, there have been many fruitful results available on dynamical behavior analysis for CDNs, including state estimation [

1], synchronization [

2,

3], and finite-/fixed-time control [

4,

5].

Synchronization, as one of the most important collective dynamical behaviors for dynamical systems, has been investigated for decades [

6,

7,

8]. To analyze synchronization performance and further design synchronization controllers, several methods have been reported, such as the master stability function method [

9], the matrix measure analysis method [

10], and the Lyapunov function method [

11]. It is noteworthy that a large portion of existing results on synchronization of CDNs focus on complete synchronization; namely, all nodes in the CDNs share the common dynamical behavior when the time approaches infinity. However, cluster synchronization finds broader applications than complete synchronization in both nature and practical applications [

12], such as during neuron discharging in the brain, multi-objective search and rescue, and military surveillance and tracking. Under a cluster synchronization setting, nodes are first split into different groups which are called clusters. Then nodes are driven to keep synchronized with their peers in the same cluster but not with those in different clusters. In the presence of multiple external reference sources, the nodes in the same cluster are then regulated to synchronize with each reference source. Up till now, a great deal of effort has been devoted to cluster synchronization of CDNs [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. For example, the prescribed-time cluster synchronization issue for complex networks is studied in [

14]. In [

15], a pinning control strategy is presented to synchronization a class of linearly coupled CDNs into different clusters. In [

16], the finite/prescribed-time cluster synchronization problem is studied for a class of CDNs with asynchronous switching. In [

17], the problem of cluster synchronization is extended to deal with parameter mismatches and time-varying delays in CDNs under impulsive control. Nevertheless, it should be pointed out that the above cluster synchronization methods are based on two ideal assumptions that (1) the data transmissions/exchanges on each node are continual at every continuous time

t and (2) the network environment, providing a two-way communication medium for the CDNs, is safe in a sense that all data transmissions/exchanges between sender nodes and receiver nodes are secure without any interruption or corruption.

Due to the openness and insufficient protection of most communication networks, CDNs are actually vulnerable to malicious attacks, such as denial-of service (DoS) attacks [

18,

19] and deception attacks [

20,

21]. Apparently, such malicious attacks may degrade the desired synchronization performance of CDNs or even destabilize the closed-loop CDNs. This thus calls for secure synchronization controllers against the adversarial effects of malicious attacks on CDNs. So far, several effective secure control methods have been developed in the literature of cyber-physical systems, e.g., [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Among the various attacks, deception attacks generally violate the integrity of transmitted data by injecting arbitrary and falsified information [

27,

28,

29]. For example, in [

27], for a class of linearly coupled complex networks under deception attacks and disturbance estimator, the synchronization issue is solved.

Apart from the security issue of CDNs aforementioned, another significant issue of synchronization control of CDNs is to preserve resource efficiency. This is because the synchronization control objective relies on the information transmission or exchange among the interacting nodes, while such an information sharing process inevitably occupies and consumes excessive resources. Event-triggered transmission mechanisms have yet shown their benefits in reducing unnecessary data transmissions and further controller updates. More specifically, compared with a conventional time-triggered mechanism where data transmissions are invoked typically at periodic times, the decisions of ‘whether or not each node’s data should be transmitted’ are determined by some well-defined events when an event-triggered mechanism is employed. Thus, event-triggered mechanisms can effectively reduce the frequency of data transmissions and further the communication resource occupancy. Naturally, the problem of event-triggered synchronization control for CDNs has been widely explored in the last decade [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. Nevertheless, it is mentioned that the above event-triggered synchronization methods all fall into the category of static triggering, wherein the triggering conditions are based on only system available information. Recently, another strategy of dynamic triggering is proposed in [

37] and has been greatly developed in the past several years. A key feature of such dynamic triggering is that some auxiliary or internal dynamic variable is introduced into the triggering conditions such that the triggering intervals can be generally prolonged. In other words, dynamic triggering can often leads to more resource efficiency than its static counterpart. Applying dynamic triggering to synchronization control problems of CDNs has also attracted great interest, see, e.g., [

38,

39,

40]. To our knowledge, there have been relatively few results available on cluster synchronization of CDNs while taking into account both dynamic event-triggered mechanism and security countermeasure against deceptive attacks, which gives rise to the second motivation of this study.

In this paper, we investigate the secure cluster synchronization problem for a class of CDNs under random deception attacks. The main contributions of this paper are listed as follows. (1) A general CDN model is formulated by taking into account both nonlinear model dynamics, multiple time-varying delays, nonlinear and delayed couplings. Unlike the linear coupled CDNs [

14], the CDN model researched in this paper can simulate actual nonlinear systems more accurately. (2) A unified secure cluster synchronization control framework is established to simultaneously address nonlinear dynamics, multiple time-varying delays, and random deceptive attacks. Most existing secure control works focus on denial-of-service (DoS) attacks or single-type synchronization (e.g., complete synchronization) [

6,

7,

8], while this paper addresses cluster synchronization with deceptive attacks and provides explicit attack tolerance bounds, which fills the gap in heterogeneous state synchronization under data tampering. (3) Tractable stability analysis and control design criteria are derived such that the resulting closed-loop CDN achieve secure cluster synchronization while maintaining efficient resource occupancy over the communication channels. A special case of secure static event-triggered cluster synchronization control design is also presented. The controller design integrates attack compensation terms to counteract the adverse effects of data tampering, and sufficient conditions for synchronization are derived via Lyapunov-Krasovskii functionals with some integral inequalities, which are less conservative than existing delay-independent criteria [

16].

The rest of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 shows the model description.

Section 3 gives the main results. In

Section 4, a numerical example is presented, and concluding remarks are given in

Section 5.

2. Preliminaries and Problem Formulation

2.1. Notation

Denote and as the set of natural numbers and non-negative integers, respectively. and stands for the set of n-dimensional real space and dimensional real spaces, respectively. Denote as identity matrix, . () means that the matrix is a positive (negative) definite matrix. The superscript ‘T’ indicates matrix transposition and ‘⊗’ is the Kronecker product. Matrices are all with appropriate dimensions without special description.

The interconnection topology among nodes is modeled by a digraph of order with a set of nodes , a set of edges , and weighted adjacency matrix , where is the weight of the directed edge satisfying if and otherwise. Moreover, it is assumed that , to avoid self-loops.

Let

be a cluster set with

and

be a partition of the initial node set

such that

, and

for

,

. Denote by

, ⋯,

, ⋯,

,

,

. Denote the total number of the nodes in the

kth cluster by

,

, where

represents the cardinality of the set. Other key notations can be found in the

Table 1.

2.2. Modeling of CDNs

Consider a class of CDNs consisting of

N interacting nodes, in which the dynamics of the

ith node,

, are described by the following coupling state-space equation

where

is the state vector of the

ith node;

are the connection weight matrices;

,

,

are continuous non-delayed and delayed nonlinear functions,

,

;

is the non-delayed output-coupling weight matrix with

,

,

;

,

,

;

stands for the delayed output-coupling weight matrix with

,

,

;

,

,

;

,

, represent the non-delayed inner-coupling matrix and delay inner-coupling matrix, respectively;

means the nonlinearly non-delayed coupling vector function and

means the nonlinearly delayed coupling vector function, where

,

,

; and

=

, ⋯,

is the control input of the

ith node. Besides, the initial state of system (

1) is defined as

,

,

,

.

Our objective is to synchronize the CDN (

1) of

N nodes with

desired heterogeneous states, which can be

different reference trajectories,

equilibrium points,

periodic orbits or

chaotic attractors, event in the presence of deception attacks. For this purpose, we denote such

desired heterogeneous states by

,

, which are defined in accordance with the following equation:

where

,

,

,

,

,

. The initial state of system (

2) is defined as

,

.

Combining the CDN in (

1) and the heterogeneous states in (

2), the objective is to design a suitable cluster synchronization controller

for each node

i belonging to the cluster

such that

for any

and

. Then, it is clear that

denotes the desired cluster synchronization pattern under the proposed synchronization controller.

Furthermore, the nonlinear functions satisfy the following mild assumption.

Assumption 1

([

1]).

There exist real constant matrices and with , , such that for any w, , the following inequality holds Remark 1.

For the nonlinear function which describes the internal dynamics of nodes in cluster k, the difference between its values at two arbitrary states w and v can be ‘sandwiched’ between two linear functions. In other words, does not grow faster than a linear rate—this prevents unbounded nonlinearity from destabilizing the network. For example, let , we can choose and . For any w and v, .

Assumption 2.

There exist scalars , such that for any , the following inequalities hold Remark 2.

For the coupling nonlinear functions and which describe interactions between nodes, the ‘size’ (Euclidean norm) of the difference between their values at two states w and v is at most a constant multiple of the ‘size’ of the state difference . For example, let , we can choose .

2.3. A Dynamic Event-Triggered Transmission Mechanism

To solve the above cluster synchronization problem, the widely-adopted synchronization controller takes the following form of

where

is the controller gain to be designed and

represents the cluster synchronization error.

It is clear that the error signal

in (

4) on node

has to be transmitted to the controller at every continuous time instant

t. This may cause excessive usage of the limited computation and communication resources of each node and the network medium. In the following section, a dynamic event-triggered mechanism is considered under which the cluster synchronization controller in (

4) can be updated in an intermittent manner.

For any

, let the triggering time sequence be denoted by

with

. Then, the following triggering mechanism specifies how the triggering times can be recursively determined

where

is positive define matrix,

,

,

,

, and

is an auxiliary dynamic variable satisfying

where

and

,

.

Remark 3.

The triggered condition in (5) means that only when the current data (error) satisfying the inequality will be triggered and released. From the sensor’s perspective, this basically means that the continuous data has no need to be persistently transmitted to the controller. Meanwhile, at the controller side, during , the controller will not be updated with any new data but instead using the previously triggered data , namely, for any . As a result, compared with the continuous-time cluster synchronization controller (4), the consumption of computation and communication resources of the sensor and controller can be significantly reduced under the above event-triggered cluster synchronization controller. On the other hand, the auxiliary dynamic variable possesses an important non-negative feature which plays an important role in reducing the frequency of data transmissions. Specifically, it is easy to get that during . Then, it follows from (6) that , which leads to for based on the comparison principle. Remark 4.

and primarily suppress unnecessary triggers by adjusting the auxiliary variable’s influence, while and directly tune the sensitivity of the error-based triggering condition—properly selecting them balances communication resource savings and synchronization performance. The Table 2 shows the selection guidelines of parameters. 2.4. Modeling of Random Deception Attacks

Once the data packet

with its time stamp

is triggered, it will be released over certain communication network or channel. Such a released data packet is considered to be important for achieving the desired cluster synchronization objective. However, most realistic communication networks suffer from inherent security vulnerabilities due to their openness or insufficient protection against malicious cyber attacks. To make the desired cluster synchronization controller resilient and secure to malicious cyber attacks, it is thus imperative to incorporate cyber attacks into the controller design. In doing so, we first present the following random deception attack model

for any

,

, where

represents the actually received data at the controller side,

denotes the deception data or signal injected by attackers over the network or during network transmission. For simplicity and without loss of generality, it is assumed that

,

,

, is a continuous function, and for

,

satisfies

,

, where

is a known positive definite matrix. The function

represents the adversary’s falsification strategy, for example, scaling, offsetting, or distorting the original error signal

to produce the attacked signal

. The matrix

H serves as a bound on the attack’s maximum allowable distortion. Such a bounding assumption on the deception signal is reasonable since (1) realistic adversaries are often energy-limited and may not be able to inject arbitrarily large data packets, and (2) arbitrarily large injection signalS may be easily detected by the existing anomaly detector via checking the data residue.

Furthermore,

in (

7) is a Bernoulli distribution variable satisfying

and

, where

is known constant. Such a stochastic variable is introduced to model the random characteristics of real-world deception attacks. Since our focus is placed on the deception attacks occurring within the network channels or during networked data transmission, it is mild to assume a homogeneous stochastic variable

for all the network channels. The Bernoulli-distributed attack model adopted in this paper is a simplified yet practical choice, and its rationale lies in two key aspects aligned with real-world scenarios: First, it effectively captures the binary ’hit-or-miss’ nature of deception attacks—in actual communication channels, an attacker either injects falsified data (attack occurs) or does not interfere (no attack), and the Bernoulli variable directly maps this discrete stochasticity. Second, the model’s statistical property (

) enables tractable mean-square stability analysis, which is critical for deriving explicit linear matrix inequality (LMI) conditions and feasible controller gains—an essential step for validating the proposed secure synchronization framework through both theoretical proofs and numerical simulations.

Remark 5.

While recent work on deception attacks focuses on output feedback PID control or switched system resilience, our study uniquely integrates dynamic event-triggered mechanisms with cluster synchronization, addressing the under-explored challenge of secure grouping in complex networks rather than full-network consensus. Unlike the static event-triggered designs, our auxiliary variable-based triggering rule (6) adaptively adjusts to random deception attacks. Compared to works handling asynchronous DoS attacks via linear auxiliary trajectories [19], we explicitly model deception attack dynamics with a Bernoulli variable and bounded disturbance matrix H, providing verifiable guidelines for H estimation that are absent in prior LMI-based resilient control frameworks. 2.5. The Problem to Be Addressed

Based on the dynamic event-triggered mechanism (

5) and attack model (

7), we are interested in constructing and design the following cluster synchronization controller

From (

5)–(

8), for

, the synchronization error dynamics can be written as

where

,

,

,

,

,

,

.

Furthermore, let

,

,

,

. The error system can be rewritten as, for

,

where

The main problem to be addressed in this paper can now be stated as follows.

Problem 1.

For the CDNs in (1), we aim to design a secure dynamic event-triggered cluster synchronization controller in the form of (8) such that the desired secure cluster synchronization objective is achieved regardless of the simultaneous effects of intermittent data transmission under (5) and random deception attacks under (7), i.e., as for any and initial condition. Before ending this section, some definitions, assumption, lemmas are recalled.

Definition 1

([

15]).

Consider . If(1) , for , and =, .

(2) D is irreducible.

Then we say .

Definition 2

([

15]).

For an matrixwith , , i, , if each block is a zero-row-sum matrix, then we say . Furthermore, if , , then we say . Assumption 3.

The coupling matrix A in (1) satisfies , . Remark 6.

The non-delay coupling matrix A and delayed coupling matrix B must have two properties. (1) For each cluster, the sum of coupling weights from any node in the cluster to all other nodes in the same cluster is zero which ensures internal cluster balance. (2) Each submatrix of A and B corresponding to a single cluster is ’irreducible’, in other words, no isolated nodes in the cluster. For example, consider a CDN with 2 clusters: , . We can choose the non-delayed coupling matrix: Lemma 1

([

41]).

For any constant positive matrix , scalar and vector function such that the following integration is well defined, then it holds that Lemma 2. (Schur Complement) Given matrices , , , where , , then if and only if Lemma 3.

For any matrices , and scalar ι, the following inequality holds For the sake of simplicity, some mathematical notations are introduced as follows.

4. An Illustrative Example

Consider a network of five nodes that are assigned into two clusters

,

. Moreover, the

ith node described as (

1) with

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

with

,

,

,

with

,

,

,

,

,

, and

Choose

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

. Via solving LMI (

33), the feasible controller gains are given as

,

,

,

,

.

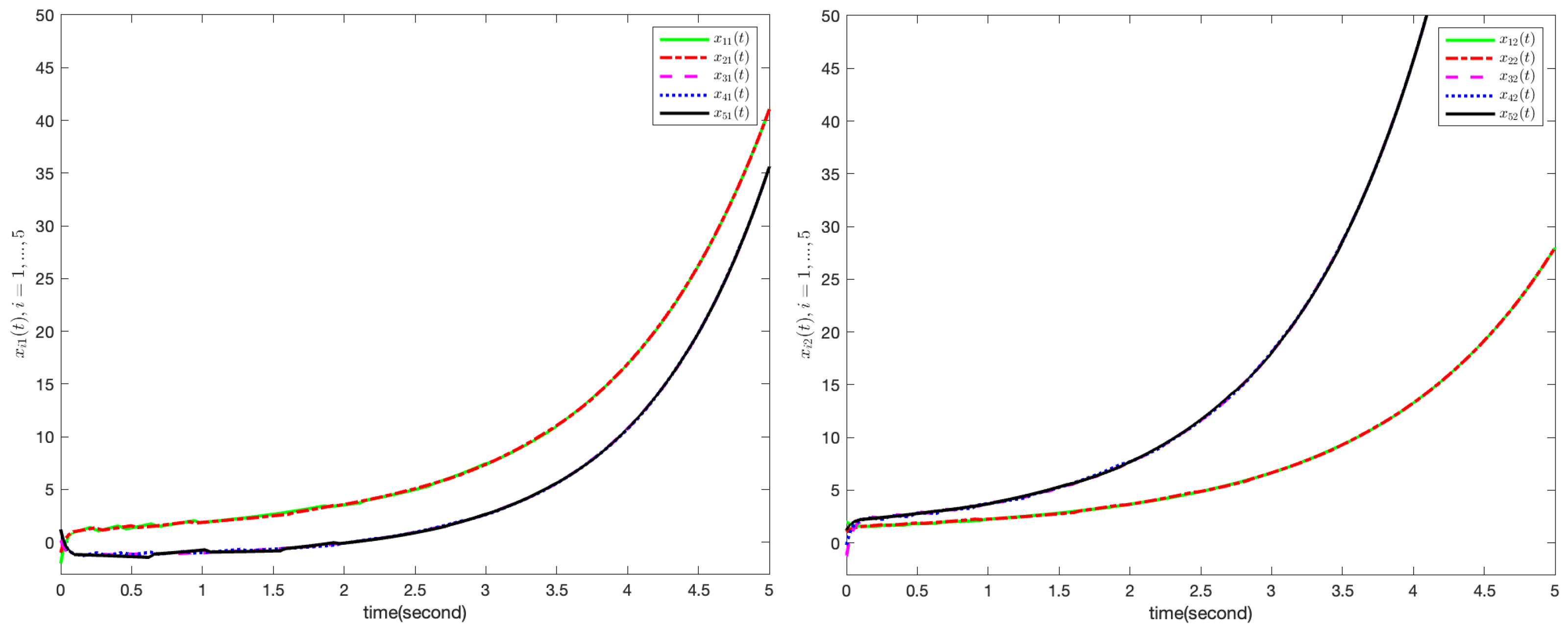

Applying the designed secure cluster synchronization controller, it is found that the CDNs can be synchronized into two clusters even in the presence of the simulated stochastic deception attacks. The related simulation results are shown in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

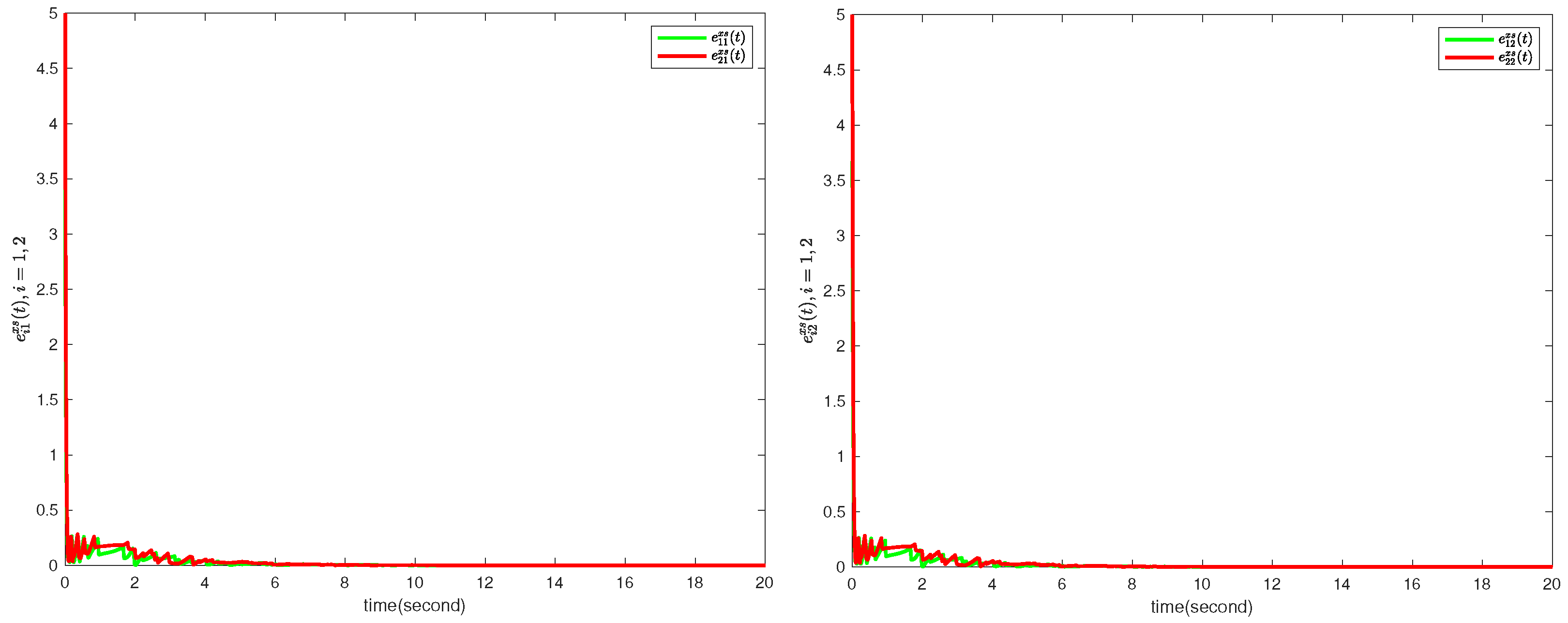

Figure 6. Specifically, from

Figure 1, it can be concluded that the nodes are not synchronized without controllers. Under the controllers, nodes in the same cluster are synchronized and not synchronized in the different cluster from

Figure 2. Moreover, as shown in

Figure 3, the trajectories of cluster errors

,

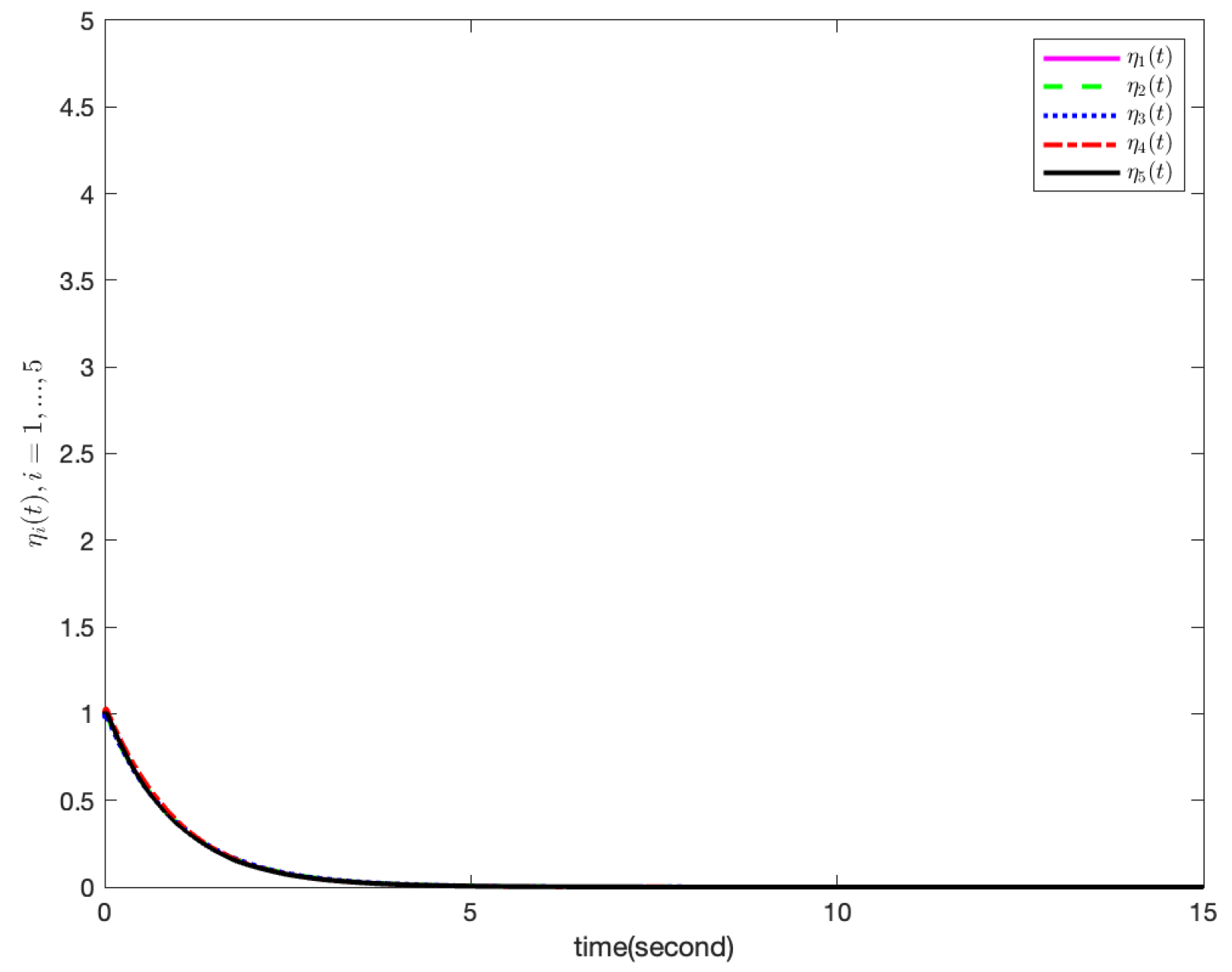

are approaching zero, such findings illustrate that the theoretical results are effective. In

Figure 4, dynamic functions

,

are described and we can conclude that the trajectories of dynamic functions

,

are approaching zero while

.

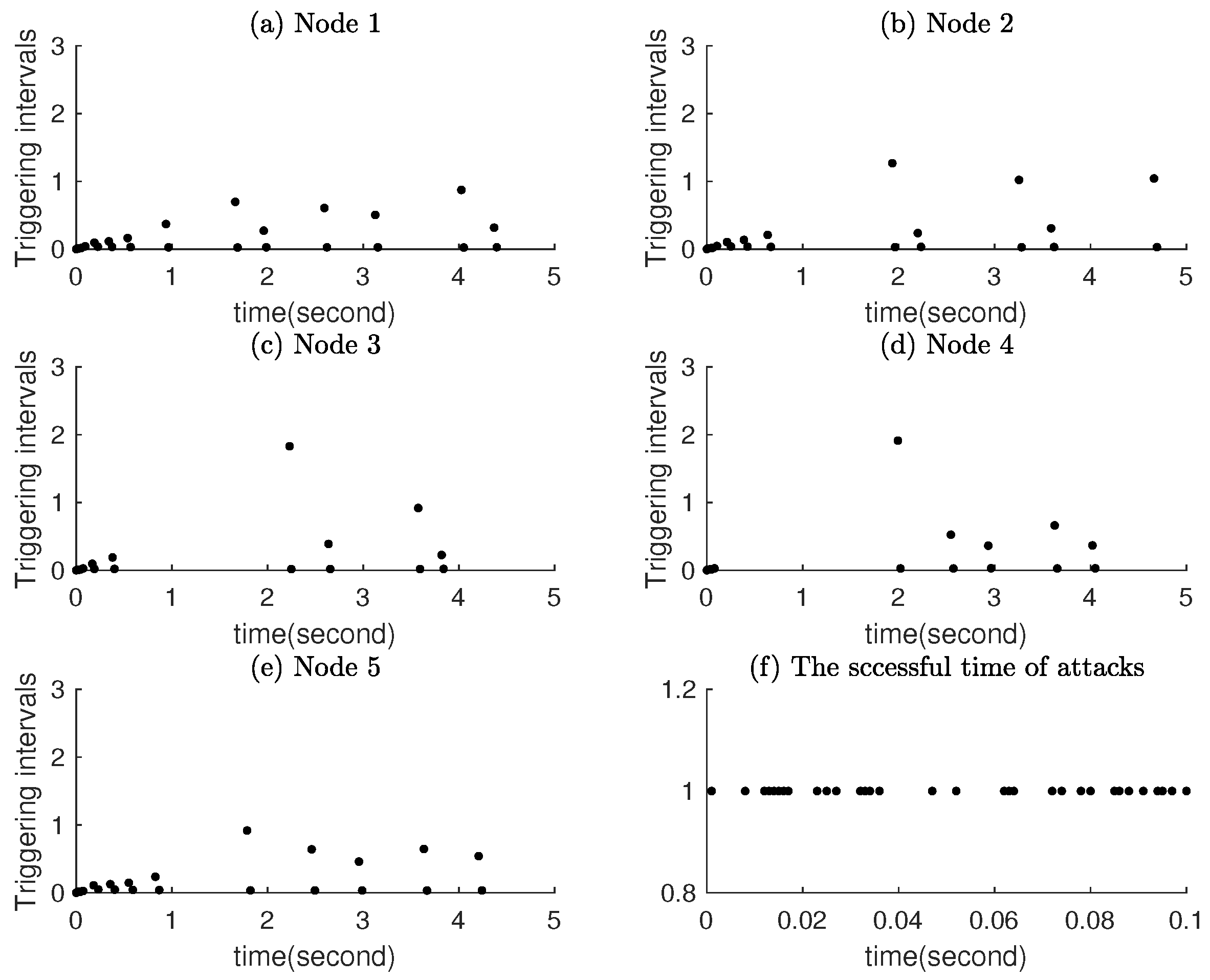

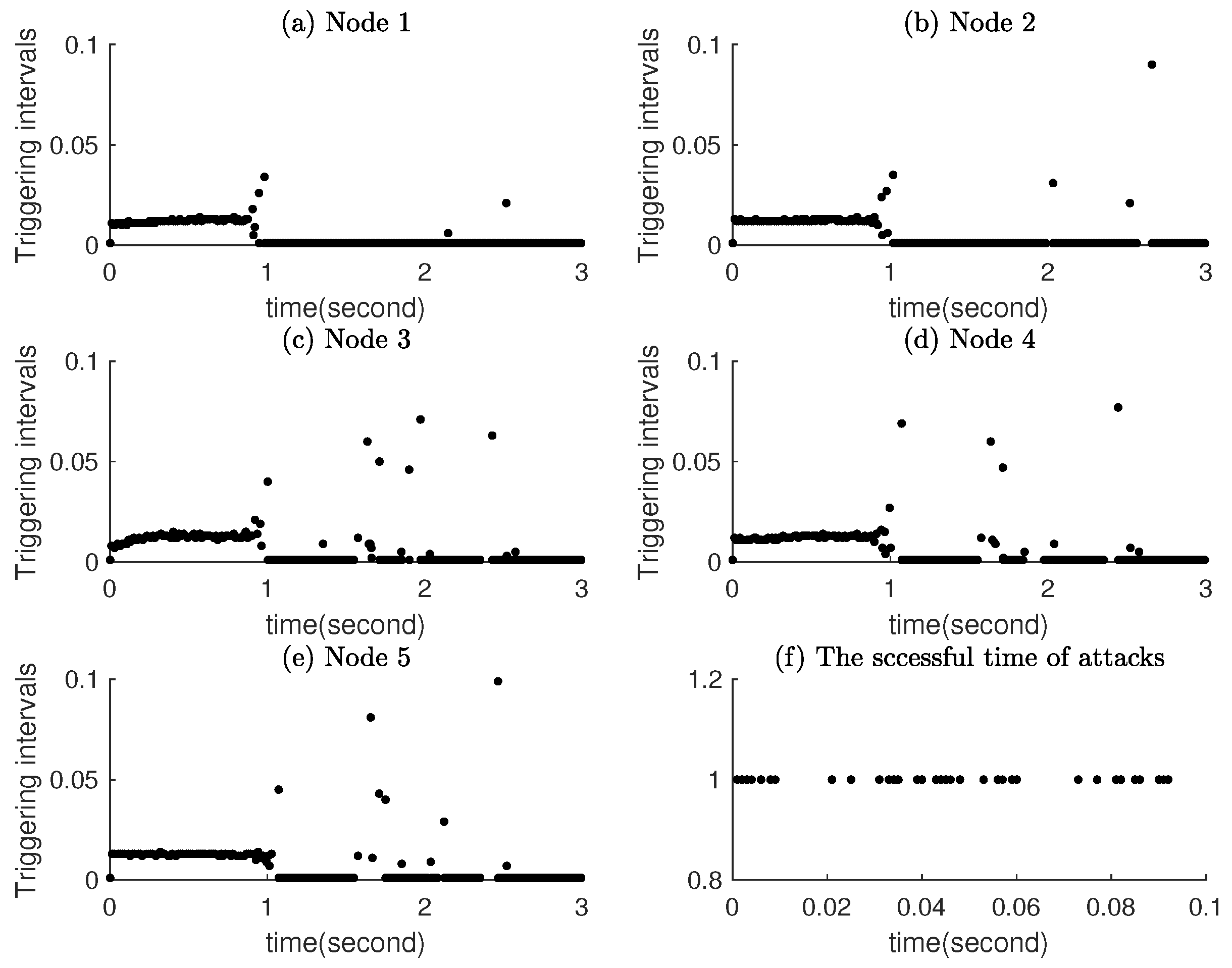

Figure 5 show the dynamical event releasing instants and intervals of nodes in the CDNs as well as the occurring instants of the simulated stochastic deception attacks.

Figure 6 show the static event releasing instants and intervals of nodes in the CDNs as well as the occurring instants of the simulated stochastic deception attacks.

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 intuitively illustrate two key improvements of the dynamic event-triggered mechanism: (1) it significantly reduces the number of triggering events; (2) it maintains more stable triggering intervals which avoided frequent unnecessary triggers caused by static threshold rigidness.