Abstract

We propose MUSE++, an advanced and lightweight speech enhancement (SE) framework that builds upon the original MUSE architecture by introducing three key improvements: a Mamba-based state space model, dynamic SNR-driven data augmentation, and an augmented multi-objective loss function. First, we replace the original multi-path enhanced Taylor (MET) transformer block with the Mamba architecture, enabling substantial reductions in model complexity and parameter count while maintaining robust enhancement capability. Second, we adopt a dynamic training strategy that varies the signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) across diverse speech samples, promoting improved generalization to real-world acoustic scenarios. Third, we expand the model’s loss framework with additional objective measures, allowing the model to be empirically tuned towards both perceptual and objective SE metrics. Comprehensive experiments conducted on the VoiceBank-DEMAND dataset demonstrate that MUSE++ delivers consistently superior performance across standard evaluation metrics, including PESQ, CSIG, CBAK, COVL, SSNR, and STOI, while reducing the number of model parameters by over 65% compared to the baseline. These results highlight MUSE++ as a highly efficient and effective solution for speech enhancement, particularly in resource-constrained and real-time deployment scenarios.

Keywords:

speech enhancement; Mamba architecture; extended loss function; lightweight neural network; dynamic SNR-based augmentation MSC:

68T07

1. Introduction

Speech enhancement (SE) is a foundational technology aimed at improving the intelligibility and perceptual quality of speech signals degraded by noise. It underpins numerous applications, including mobile telephony, hearing aids, smart assistants, remote conferencing, and automatic speech recognition [1,2,3]. Over the past decades, SE methodologies have undergone significant evolution, transitioning from statistical signal processing approaches [4,5] and classical frequency-domain techniques [2,6] to complex deep-learning models capable of real-time deployment under various acoustic conditions [7,8,9,10,11].

Early SE work mainly relied on frequency-domain statistical models, such as spectral subtraction [4], Wiener, and MMSE filters [5]. These approaches primarily focused on magnitude estimation, with noisy phase components directly used for waveform synthesis [6]. While satisfactory for stationary environments, their performance rapidly degrades in dynamic, nonstationary noise, and their neglect of phase information poses fundamental limits to intelligibility [1,2,6].

The advent of deep neural networks revolutionized SE: deep neural network (DNN), convolutional neural network (CNN), long-short term memory (LSTM), and U-Net models enabled powerful data-driven learning, facilitating the joint, adaptive mapping of noisy and clean speech spectrograms [2,12,13,14]. Despite the popularity of magnitude-only approaches, where networks estimate clean magnitude and retain the noisy phase [1,9,12], attention has increasingly turned to enhancing phase information directly. Recent milestone works, including PHASEN [14], dual-path [12], and parallel magnitude-phase models [15,16], demonstrate that phase-aware modeling yields substantial gains in perceived quality, especially in low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and adverse acoustic conditions [6,17].

In parallel, there is a growing emphasis on lightweight and resource-efficient SE models—particularly for mobile, edge, and real-time scenarios where memory, computation, or power are constrained. Recent surveys [3,8,10] and benchmark challenges have identified architectural strategies, such as compact convolutional blocks, grouped operations, efficient attention, and neural architecture search, that enable SE algorithms to operate with drastically fewer parameters and floating point operations (FLOPs), often without significant performance sacrifice. Representative models include GTCRN [8], FSPEN [18], LiSenNet [19], CTSE-Net [10], and LDSTransformer [11]. These leverage encoder–decoder pruning, bottleneck compression, sub-band processing, and novel gating/attention strategies for high efficiency.

The multi-path enhanced Taylor transformer-based U-Net for speech enhancement (MUSE) framework [7], for example, integrates flexible receptive fields and multi-path attention mechanisms on a U-Net backbone, achieving strong denoising performance at minimal computational cost. Similarly, UL-UNAS [8] employs neural architecture search to optimize U-Net variants for microdevices, combining tailored activation functions and time-frequency attention. Lightweight models such as those for drone noise suppression [11], real-time speech [20], and multi-microphone post-filtering [9,10] exemplify the field’s direction.

The ongoing shift toward multi-modal and cross-domain SE is particularly noteworthy, with approaches leveraging visual cues (e.g., lip movement) [21,22], bone-conduction signals [23], and end-to-end fusion strategies [17,24] to bolster robustness under challenging conditions. Recent studies have further emphasized the capabilities of audio-driven models in areas such as motion talking head generation [25] and wearable device sensing [26], illustrating the broad applicability of acoustic cues beyond conventional SE frameworks. These advancements are frequently paired with lightweight architectures to facilitate practical deployment in wearable devices, Internet of Things (IoT) systems, and embedded platforms.

In summary, modern SE research is characterized by the following:

- A shift from classical magnitude-centric, frequency-domain methods to sophisticated time-frequency and time-domain deep models [2,12,17].

- Recognition of phase modeling as critical, driving complex spectral and parallel magnitude-phase innovations [6,14,15,16].

- The rise of lightweight, low-resource models through efficient architecture, pruning, and specialized attention/gating mechanisms [7,8,9,10,11].

- Expansion towards multi-modal SE with audio–visual fusion, bone conduction, and cross-modal attention for robust real-world deployment [21,22,23].

These advancements enable enhanced perceptual speech quality, real-time processing, and scalable implementation for increasingly diverse and challenging application scenarios.

Building on the MUSE architecture [7] as our foundational framework, we introduce MUSE++, which incorporates a series of targeted enhancements to achieve a more lightweight and computationally efficient SE model—while maintaining, and in some cases improving, overall performance. Central to these improvements is the replacement of the original multi-path enhanced Taylor (MET) transformer module with the Mamba architecture [27,28], a recent innovation that delivers comparable SE results while significantly reducing both computational demands and model size. This modification optimizes the system for deployment in resource-limited environments, yet preserves high-quality enhancement capabilities.

Recent advances in SE have frequently utilized self-attention architectures, such as transformers, given their strong sequence modeling capabilities. However, self-attention mechanisms generally incur quadratic computational complexity with respect to sequence length, which limits their practicality for real-time or embedded speech applications. To address this limitation, lightweight transformer variants such as Performer [29] and Linformer [30] have been proposed to improve efficiency in long sequence modeling. Performer achieves linear scalability by approximating attention with kernel methods, while Linformer reduces memory consumption through low-rank approximation of the attention matrix, both resulting in faster and more resource-efficient processing.

In contrast, state-space models (SSMs)—and especially Mamba—present distinct advantages. SSMs achieve true linear scaling in both computation and memory, making them ideal for processing long speech sequences efficiently. Whereas Performer and Linformer enhance scalability by modifying attention mechanisms, Mamba takes a fundamentally different approach, using a structured state=space framework to capture long-range dependencies without relying on attention.

Mamba’s selective state-space mechanism enables the model to efficiently aggregate information from both local and distant temporal contexts, providing robust modeling capabilities with significantly reduced computational cost and parameter size. This design is particularly well-suited for real-time and resource-constrained environments, where compact models and rapid inference are essential. After reviewing various alternatives, we selected Mamba for this work because it represents a good balance of efficiency, modeling power, and practical suitability for SE in low-resource scenarios.

Furthermore, recent studies [31,32] have directly investigated the use of Mamba as a substitute for transformer blocks in SE architectures. These works demonstrate that Mamba-based models can achieve performance comparable to, or better than, traditional transformer networks, while offering significant reductions in model complexity and computational demands. Our work builds on these findings and empirically validates the practical benefits of adopting the Mamba block for SE. We acknowledge, however, that our focus is on empirical performance and system integration; rigorous mathematical analysis of the expressive capacity and convergence properties of Mamba, specifically for SE, is left as an important direction for future study.

To further support generalization and practical robustness, we employ a dynamic training regime that systematically varies signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) across diverse speech samples, ensuring the model encounters a wide range of acoustic scenarios during learning. This approach fosters stronger feature representation for both clean and noisy speech. We also introduce an expanded set of loss functions—utilizing several objective measures—to guide the training process more effectively. The combined use of these losses drives improved outcomes across different perceptual and objective SE benchmarks. Rigorous evaluations on the VoiceBank-DEMAND dataset [33,34] revealed that MUSE++ not only achieves marked reductions in model size and complexity versus the original MUSE but also consistently surpasses it on key SE performance metrics.

Although the core components employed in this study—including the Mamba sequence model, dynamic SNR training, and multi-resolution loss functions—are based on recent innovations, our main contribution lies in their thoughtful adaptation, systematic integration, and thorough experimentation within the MUSE framework. The coordinated combination and practical engineering of these elements address non-trivial challenges in building a lightweight, resource-efficient SE system suitable for real-world applications. Our study shows that this deliberate integration yields substantial gains in efficiency and robust enhancement performance, as evidenced by comprehensive evaluation and ablation studies.

The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

- We propose a novel SE architecture that systematically integrates the Mamba state-space model in place of transformer, achieving substantial reductions in model complexity while maintaining high denoising performance, as supported by recent literature.

- We adopt a dynamic data augmentation strategy based on varying signal-to-noise ratios, which strengthens the model’s robustness and generalization to diverse acoustic conditions.

- We introduce a multi-objective training paradigm, integrating additional time, frequency, and consistency loss components to promote improved perceptual and objective SE outcomes.

Collectively, these innovations offer an effective solution for deep-learning-based SE, as evidenced by the results on widely recognized benchmark datasets.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 presents a concise overview of the backbone model, MUSE. Section 3 details our three proposed enhancements to MUSE. The experimental setup, comparative results, and related discussion are described in Section 4 and Section 5. Finally, Section 6 offers concluding remarks and a summary of the work.

2. Introduction to the Backbone MUSE Method

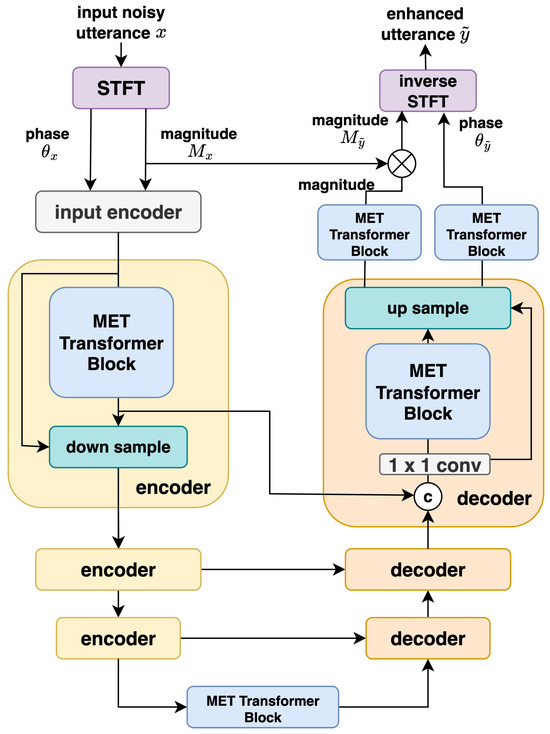

MUSE (multi-path enhanced Taylor-transformer-based U-Net for speech enhancement) [7] is a lightweight yet high-performing architecture for SE, comprising merely 0.51 M parameters. It effectively models both global and local time-frequency dependencies in noisy speech, circumventing the substantial memory and computational demands typically associated with deeper U-Net- and Transformer-based solutions. An overview of the MUSE framework is provided in Figure 1. For clarity, detailed module explanations are omitted due to complexity, and interested readers are referred to [7] for further details.

Figure 1.

An overview of the MUSE framework (drawn according to [15]).

2.1. Input Representation and Data Flow

Given a time-domain input signal x, the short-time Fourier transform (STFT) produces a magnitude spectrogram and phase spectrogram for T time frames and F frequency bins:

To balance the dynamic range and facilitate learning, the magnitude is compressed using a power-law transform:

with typical .

The input tensor to the U-Net is then formed by concatenating the compressed magnitude and raw phase:

This tensor passes through the encoder–decoder skip-connected U-Net. At the output, enhanced magnitude and phase features are produced and then recombined for waveform synthesis by inverse STFT (ISTFT).

2.2. MET Transformer Block

The MET Transformer block mainly consists of two modules: deformable embedding and MET transformer, which are briefly explained as follows:

- Deformable embedding module:Naive convolutional kernels struggle with adapting to complex spectrogram structures common in speech. MUSE employs a deformable embedding (DE) module based on depthwise separable and deformable convolutions (DSDCN):where are learnable receptive field offsets. This design enables multiscale, adaptive aggregation of features with minimal parameter count and incorporates Hardswish activation to extract richer nonlinear patterns.

- MET transformer: The principal encoder/decoder block is the multi-path enhanced Taylor (MET) transformer, comprising three parallel branches:

- −

- Taylor Multi-head Self-Attention (T-MSA) (Branch 1):This approximates softmax nonlinearity using a Taylor expansion, reducing computational cost:where are the query, key, and value matrices, respectively; i indexes the output position; N is the sequence length; and D is the feature dimension.

- −

- Channel and Spatial Attention (CSA) (Branches 1 and 2):This complements attention modeling via two branches. Channel attention uses global average pooling and convolution:Spatial attention stacks and depthwise convolutions with GELU activation:

The outputs are fused element-wise with T-MSA and residual connections, followed by normalization and feed-forward layers.

2.3. Dense Convolution Codec

The input and output encoders adopt a dilated Dense-Net architecture based on MP-SENet, using dilation rates . This extends the receptive field efficiently:

2.4. Model Training and Output

The MUSE model is trained using a composite loss function combining multiple objectives [7]:

where to are weights; and , , , and are the metric, magnitude, phase, and complex losses, respectively.

The metric loss employs a generative-adversarial-network (GAN)-based discriminator to predict perceptual evaluation of speech quality (PESQ) scores between clean and enhanced magnitude spectra, guiding the generator to achieve high perceptual quality. For details of each loss term, see [15,16].

Enhanced magnitude and phase features are recombined via the inverse STFT (ISTFT) to generate the final denoised waveform:

3. Proposed Framework: MUSE++

While the original MUSE framework achieves strong performance, its broader applicability might be limited by certain architectural and evaluation constraints. Specifically, although the MET transformer backbone is more efficient than are traditional self-attention mechanisms, it continues to impose considerable computational overhead, restricting model compactness and complicating deployment on resource-constrained devices. Moreover, reliance on static data augmentation and a fixed-loss design can hinder the model’s robustness and generalization in practical scenarios.

To overcome these challenges and further improve both efficiency and generalization, we present MUSE++, which is characterized by three core methodological innovations:

- Replacement of the MET transformer block with a 1D Mamba state-space model, simplifying the architecture and reducing complexity while retaining the ability to model long-range dependencies.

- Implementation of dynamic SNR-based data mixing, permitting the model to train under a broader variety of noise conditions and thus enhancing generalization to real-world acoustic environments.

- Adoption of an expanded multi-objective loss framework, which provides richer, multidimensional supervision and facilitates more comprehensive enhancement.

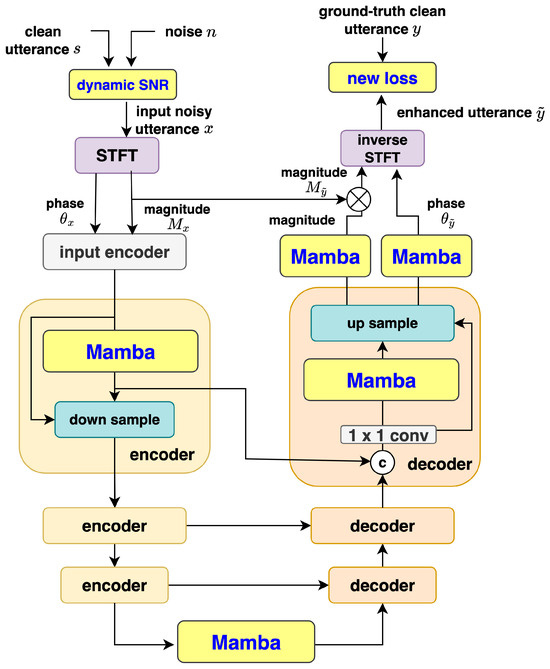

The overall MUSE++ framework is depicted in Figure 2, and the following subsections describe each aspect in detail.

Figure 2.

Diagram of the proposed MUSE++ framework architecture, highlighting the flow of compressed magnitude and phase features through a multi-level U-Net. Key components include dense convolutional encoders and Mamba-2 blocks for sequence modeling, along with the integration of dynamic SNR augmentation and multi-objective loss functions.

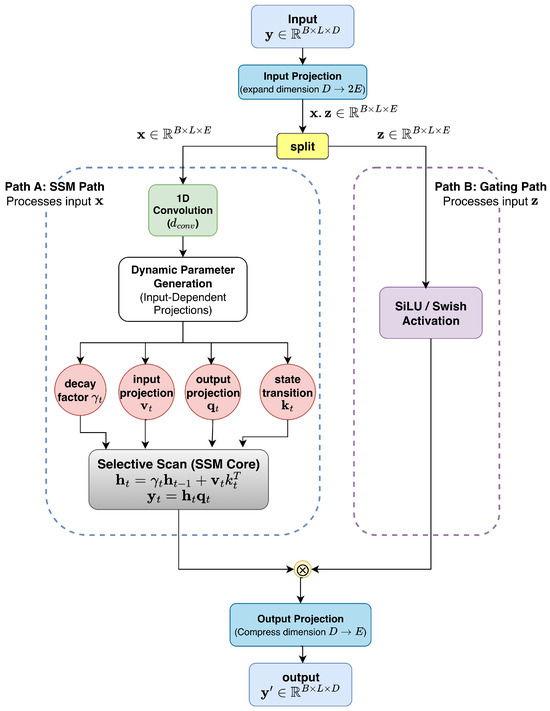

3.1. Method 1: Introducing 1D Mamba

The standard transformer architectures, including the Taylor-based transformer module in the original MUSE, scale quadratically with the input sequence length, placing a heavy burden on computational and memory resources. Mamba [27,28] is a novel neural sequence modeling architecture based on structured state0space models (SSMs), in which both inference time and memory consumption increase linearly with sequence length. This allows for practical long-term dependency modeling and efficient implementation.

A general state-space model for sequences is defined as follows:

where is the input at time t, is the hidden state, is the output, and are learned functions or matrices that can depend on the input .

For efficient processing, Mamba updates and outputs the state as follows [27]:

where all vectors () are projections of , and ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication.

A further streamlined variant, Mamba-2 [28], achieves even greater efficiency via the following:

Here, is a decay (forgetting) factor computed from the input.

Mamba-2 operates on input tensors of shape (batch size B, sequence length L, channel dimension D). The input is projected, split into SSM and gating branches, processed as described, and then re-merged. This design supports deep sequence modeling with high efficiency and flexibility, combining global context with dynamic gating.

The operational diagram of the Mamba-2 module is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Block diagram of the Mamba-2 module as used in MUSE++. The figure illustrates the main stages—input projection, state update with input-dependent parameters, dynamic gating, and output computation—demonstrating efficient capture of long-range dependencies with low computational cost.

In the presented network, we replace the MET transformer block in MUSE with Mamba-2 and use a residual connection:

This preserves a broad receptive field and sequence modeling strength while dramatically reducing parameter count and computational burden, making MUSE++ suitable for real-time or edge applications.

It should be noted that our adoption of the 1D Mamba block as a replacement for the transformer module in SE is primarily motivated by recent empirical studies [31,32], which have demonstrated that Mamba-based architectures can maintain or improve performance with reduced model complexity. While our current work does not include new theoretical analyses regarding convergence or representational capacity, we highlight this as a valuable direction for future investigation.

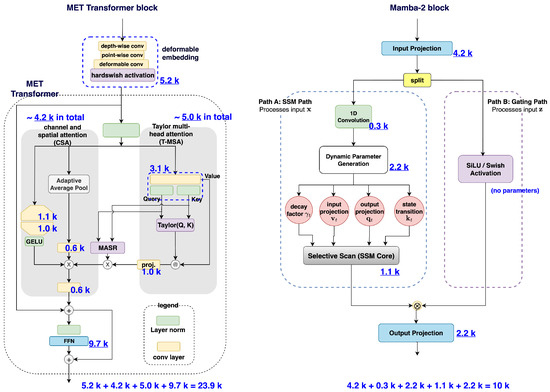

To better highlight the reduction in parameter count achieved by replacing the MET transformer block in the original MUSE architecture with the Mamba-2 block, we directly compare the actual model configurations used in our evaluation experiments (as detailed in the subsequent experimental section). Figure 4 displays the architectures and parameter counts of the MET transformer block and the Mamba-2 block at encoder level 2—the layer with the greatest number of parameters among all encoder and decoder levels—as well as their respective submodules. As shown, the MET transformer block contains approximately 23.9 k parameters, whereas the Mamba-2 block has only 10 k, marking a clear reduction. Therefore, this substitution is expected to result in a significantly lower overall parameter count for MUSE++ compared to the original MUSE.

Figure 4.

Parameter count comparison for the MET transformer (MUSE) and Mamba-2 (MUSE++) blocks at encoder level 2—the layer with the largest number of parameters among all encoder and decoder levels. The numbers with underlines show the parameter counts of major components.

3.2. Method 2: Dynamic SNR Data Augmentation

While traditional MUSE relies on pre-generated noisy–clean utterance pairs with fixed SNRs, potentially limiting robustness to diverse real-world conditions, we adopt a dynamic, on-the-fly mixing strategy to enhance training diversity. For each clean utterance and a randomly sampled noise segment n, a target SNR value is uniformly drawn from the interval , dB. The noise signal is then appropriately scaled and combined with the clean speech to synthesize the noisy input as:

where denotes the continuous uniform distribution over the interval , and and denote the power of the clean speech and noise waveforms, respectively. This augmentation scheme effectively transforms a finite dataset into an unbounded training resource, compelling the model to learn under a wide spectrum of noise conditions and thereby enhancing its generalization capability.

3.3. Method 3: Augmented Multi-Objective Loss

While MUSE adopts several loss terms, further performance gains can be realized by broadening the loss design. Let denote clean and enhanced signals, and their STFT spectrograms. We introduce three additional loss components:

- STFT Consistency Loss () [15]: The STFT consistency loss measures how close the enhanced complex spectrogram is to being consistent, which means that should equal the STFT of its inverse STFT. This loss is defined aswhere denotes the squared norm over all time-frequency bins, and is the expectation operator over all the utterances in the training set. Minimizing this loss encourages the spectrogram to correspond to a valid time-domain signal.

- Time-domain Loss () [15]: This loss directly evaluates auditory waveform closeness between generated and clean utterances:

- Multi-resolution STFT Loss () [18]: This loss averages the magnitude and complex STFT losses across multiple time-frequency resolutions:where each single-resolution loss at resolution s (determined by fast Fourier transform (FFT) size, window length, and hop size) is defined as follows:where and denote the STFTs of y and , respectively computed using the parameters for resolution s; and , are hyperparameter weights.

Accordingly, the loss function formulated for optimizing the MUSE++ framework is expressed as

where corresponds to the baseline MUSE objective defined in Equation (9). The auxiliary terms , , and , presented in Equations (21), (22), and (23), respectively, serve to enhance the performance of the model. The contributions of these auxiliary losses are modulated by the weighting coefficients , , and .

These three advances—Mamba sequence modeling, dynamic data mixing, and enhanced loss design—jointly form the basis of the proposed MUSE++ framework, enabling efficient, robust, and high-quality SE.

4. Experimental Setup

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed MUSE++ framework, we conducted experiments on the VoiceBank-DEMAND corpus [33,34], a widely used benchmark that combines clean speech samples from VoiceBank with a diverse set of noise types from the DEMAND database. The training set comprises 11,572 utterances from 28 distinct speakers, while the test set contains 824 utterances from two unseen speakers; approximately 200 examples are reserved for validation.

During standard training, clean speech is mixed with ten categories of DEMAND noise at four fixed SNRs: 0, 5, 10, and 15 dB. By contrast, our dynamic SNR data augmentation strategy (Section 3.2) mixes clean utterances with noise at randomly selected SNRs sampled uniformly from [−5 dB, 20 dB]. This broader SNR range is partially motivated by practices in the DNS Challenge dataset [35], where including a wider SNR range during training has been shown to substantially benefit real-world SE performance. For testing, five noise types from DEMAND were used with SNRs set at 2.5, 7.5, 12.5, and 17.5,dB. Key experimental arrangements were as follows:

- Data Preprocessing and Training Protocol: All speech waveforms were normalized to zero mean and unit variance prior to model input. The waveforms were uniformly segmented into 30,700 samples, with an FFT size of 510, a window length of 510, a hop length of 100, and a sample rate of 16 kHz. Training was performed over 100 epochs using the AdamW optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.0005, a learning rate decay of 0.99, a weight decay of , and a batch size of 2. Early stopping was applied if validation loss did not improve for 10 consecutive epochs.

- Model Architecture Configuration: For MUSE++, the architecture is structured as a three-level U-Net encoder–decoder with dense channel dimension set to 16. The sequence of channel dimensions in the U-Net is, with channels doubling at each downsampling layer. After spectral decomposition, output feature tensors are rearranged into one-dimensional sequences for input to the Mamba-2 blocks. The Mamba-2 modules were configured with state size , local convolution width , and block expansion parameter .

- Loss Function Configuration: For the multi-resolution STFT loss in Equation (23), three spectrogram configurations were employed: [FFT size, window length, hop size] = [510, 510, 100], [800, 800, 200], [320, 320, 80]. The loss function weights in Equations (9) and (25) were set as: , , , , , , and . The STFT consistency loss weights in Equation (24) were set as: and . These parameter choices are consistent with previous works, specifically MUSE [7] and MPSENet [15,16], with MPSENet serving as the main baseline for the development and comparison of MUSE.

- Implementation Details: The front-end dense encoder and back-end mask and phase decoders followed the MP-SENet design, with dilated convolutions with dilation rates 1, 2, 4, 8 and dense skip connections being employed. The magnitude mask was estimated with a learnable Sigmoid activation with the initial parameter set to 2.0. Our implementation was built upon the official MUSE codebase, with modifications introduced specifically for the Mamba-2 integration, dynamic SNR augmentation, and multi-objective loss functions.

- Hardware and Efficiency Measurement: All experiments were conducted on an NVIDIA RTX 3060 GPU with 12 GB memory. Model parameter counts were calculated using PyTorch 2.8’s built-in parameter counting utilities. Inference latency was measured by processing single utterances (batch size 1) and averaging the runtime across the entire test set. Memory consumption during inference was monitored using NVIDIA’s System Management Interface (nvidia-smi).

- Reproducibility: To ensure full reproducibility, our modified codebase, including all architectural changes and training configurations, will be made publicly available upon manuscript acceptance. The released code will include detailed setup instructions and pre-trained model checkpoints.

To benchmark SE performance, we employed six widely adopted objective metrics, each assessing different aspects of the enhanced speech signal:

- Perceptual Evaluation of Speech Quality (PESQ) [36]: The range is from to 4.5, with higher values indicating better quality. It objectively predicts listeners’ mean opinion scores (MOS).

- Short-Time Objective Intelligibility (STOI) [37]: Scores range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater intelligibility.

- Segmental Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SSNR) [38]: This quantifies the segmental SNR over an utterance, with higher values reflecting greater noise reduction.

- Composite Overall Quality (COVL) [38]: The range is from 0 to 5, and this is an objective MOS predictor for perceived overall speech quality.

- Composite Signal Distortion (CSIG) [38]: This an MOS scale for signal distortion, ranging from 0 to 5, with higher values denoting less distortion.

- Composite Background Noise (CBAK) [38]: This is an MOS for background noise intrusiveness, ranging from 0 to 5, with higher values indicating better noise suppression.

These standardized metrics enable objective comparison with the MUSE baseline and other state-of-the-art enhancement models.

5. Results and Discussions

5.1. Overall Performance Evaluation

Table 1 presents the mean (average) scores for the SE evaluation metrics, comparing the original MUSE baseline (as reported and as reproduced using official code) with the proposed MUSE++ across several standard metrics. The following points elaborate on the observed results and their significance:

Table 1.

The mean (average) of various SE performance scores over the all test set for the MUSE baseline (as reported in [7] and as reproduced using official code) and for the proposed MUSE++.

- Reproducibility of MUSE: The MUSE (reported) and MUSE (reproduced) results closely align, confirming that the official implementation is reliable. Minor differences might have arisen due to randomness, experimental environment, or minor changes in code or settings.

- Metric-wise Improvements:

- PESQ: MUSE++ achieves a slightly higher score than the baselines, indicating improved perceptual speech quality.

- CSIG: The enhanced CSIG score in MUSE++ reflects reduced signal distortion and better preservation of the clean speech signal.

- CBAK: A modest increase signifies more effective suppression of background noise, resulting in a less intrusive listening experience.

- COVL: The overall quality (COVL) is highest for MUSE++, representing the most favorable subjective impression of the enhanced audio.

- SSNR: MUSE++ attains a substantial increase in segmental SNR, providing a direct measure of improved noise reduction effectiveness.

- STOI: The STOI score remains highest or comparable in MUSE++, highlighting that speech intelligibility is fully preserved even with aggressive model compression.

Table 2 reports the standard deviation (i.e., variation) for each metric. Here, MUSE++ generally exhibits lower or similar variability compared to reproduced MUSE, suggesting more stable outputs overall. For example, the standard deviation for PESQ is slightly reduced (0.6476 for MUSE++ vs. 0.6865 for MUSE), and for CSIG, it is lower as well (0.4525 vs. 0.5093). Other metrics, including COVL and STOI, show similar trends, confirming that MUSE++ not only improves effectiveness but also reliability across different test samples.

Table 2.

The standard deviation of various SE performance scores over the all test set for the MUSE baseline (as reproduced using official code) and for the proposed MUSE++.

Table 3 presents a comparison of model efficiency and computational cost between the reproduced MUSE baseline and MUSE++. Four key metrics are shown: the number of parameters (#Para. in millions), real-time factor (RTF), inference time for the test set (IFT, in seconds), and throughput (THP, in utterances per second). The results highlight clear advantages for MUSE++. It utilizes only 0.17 million parameters, a significant reduction from MUSE’s 0.51 million—about three times fewer parameters—making MUSE++ much more lightweight and efficient. The real-time factor (RTF) is also lower for MUSE++ (0.0116 vs. 0.1038), meaning it processes audio nearly nine times faster relative to input duration. Inference time (IFT) for the entire test set is drastically reduced from 218 s (MUSE) to 27 s (MUSE++), indicating a major speed improvement for large-scale or real-time applications. Finally, throughput (THP) rises dramatically, with MUSE++ processing 85.98 utterances per second compared to only 9.64 for the baseline.

Table 3.

The number of parameters (#Para. in M; fewer is better), the real-time factor (RTF, the ratio of the processing time to the original audio duration; lower is better), the inference time for the whole test set (IFT in second; lower is better), and the throughput (THP, amount processed per second; higher is better) of the MUSE baseline (as reproduced using official code) and for the proposed MUSE++.

Accordingly, MUSE++ achieves substantial gains in model compactness and computational efficiency, with faster inference and greater processing throughput. These improvements make MUSE++ highly practical for deployment in real-time or resource-constrained environments while retaining the strong performance established in the previous tables.

In conclusion, the advances embodied in MUSE++ result from both architectural innovation and improved training strategies. Our proposed method achieves substantial gains not only in model efficiency and parameter reduction but also in SE quality, with clear improvements observed in most objective metrics. This demonstrates that MUSE++ delivers a solution that is both highly efficient and broadly more effective than previous state-of-the-art models.

5.2. SNR-Wise Evaluation of Enhancement Results

As previously discussed, MUSE++ demonstrates superior overall average performance compared to MUSE across all test utterances, including those with varying SNR conditions. To further investigate the consistency and robustness of these improvements, Table 4 provides a detailed breakdown of performance for each standard SE metric across individual test subsets corresponding to four distinct SNR levels (2.5, 7.5, 12.5, and 17.5 dB).

Table 4.

The mean (average) of various SE performance scores for MUSE and MUSE++ across various SNRs.

From these results, it is evident that MUSE++ consistently outperforms or matches the baseline MUSE across almost all metrics and SNR categories. Importantly, the advantages of MUSE++ are not restricted to only high or low SNR settings; rather, they persist through the full range of noisy environments evaluated. This underscores the strong generalization and adaptability of the proposed architecture, indicating its reliability and effectiveness for both adverse and favorable acoustic scenarios.

5.3. Ablation Study of MUSE++

Table 5 provides a comprehensive comparison of SE performance among the reproduced MUSE baseline, MUSE++ (combining all three improvements), and variants where each technique is applied individually. The main observations are as follows:

Table 5.

SE performance comparison among the reproduced MUSE baseline, the proposed MUSE++ (integrating Mamba-2, dynamic SNR, and augmented loss), and ablation variants with single improvements.

- MUSE++: Best overall performance and efficiency. By integrating Mamba, dynamic SNR training, and augmented loss, MUSE++ delivers consistently strong results across all evaluation metrics while reducing the parameter count to just M. This demonstrates that these techniques, when combined, can achieve state-of-the-art enhancement with minimal model complexity.

- Mamba-2 only: Maximum compression, moderate performance. The use of Mamba-2 alone shrinks the parameter count from M to M, offering significant efficiency gains. However, the individual performance on PESQ, CSIG, CBAK, and COVL is somewhat reduced, indicating that architectural improvements should ideally be paired with other techniques for optimal results.

- Dynamic SNR only: Excellent subjective and intelligibility gains. Employing only dynamic SNR during training leads to the best PESQ, CSIG, CBAK, COVL, and STOI values. This highlights the effectiveness of varied SNR data in training for boosting the model’s robustness and perceptual quality. The trade-off, however, is that its parameter count remains high ( M).

- Augmented loss only: Outstanding noise suppression. Using only the augmented loss yields the highest SSNR (), together with strong results in COVL, CSIG, CBAK, and STOI, showing that a composite loss design can greatly benefit overall enhancement quality and noise reduction.

- Synergy in MUSE++: The integrated approach in MUSE++ leverages complementary strengths of all three enhancements, maintaining robust or superior scores in every metric and offering the lowest model size. While single techniques each provide specific benefits, their combination achieves optimal balance between performance, efficiency, and practical applicability.

In summary, individual enhancements each contribute significantly to model performance, but MUSE++ distinguishes itself by providing the best trade-off between enhancement quality, computational efficiency, and suitability for deployment.

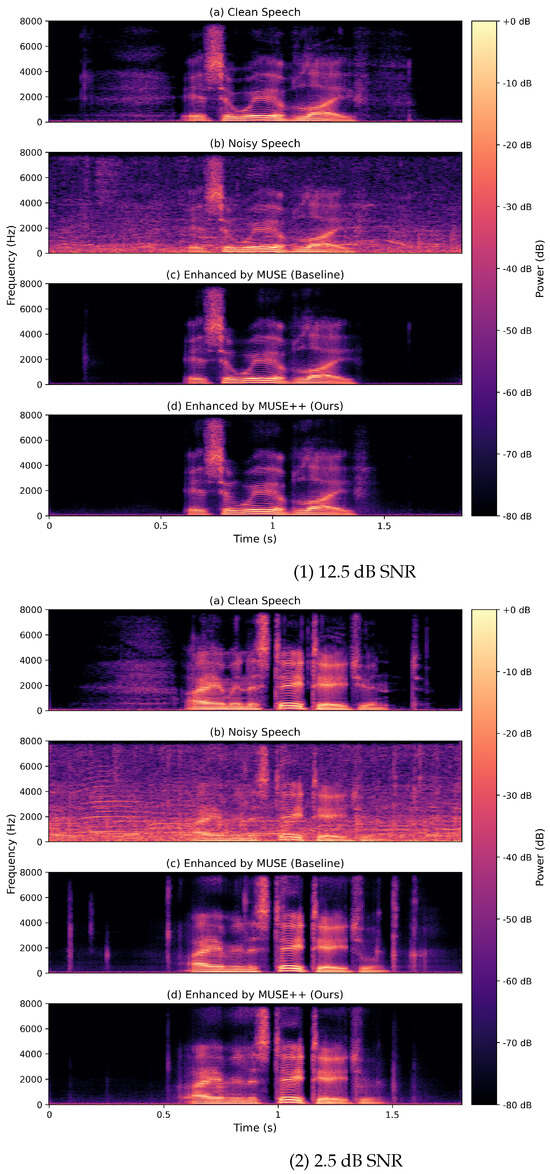

5.4. Qualitative Evaluation Using Spectrograms

Beyond objective SE scores, we also employed (magnitude) spectrogram analysis to qualitatively compare MUSE and MUSE++. Figure 5 shows speech signals subjected to moderate (12.5 dB SNR) and severe (2.5 dB SNR) cafe noise, displayed as clean, noisy, and enhanced spectrograms. This visual comparison provides intuitive evidence of each model’s ability to suppress noise and restore speech structure, complementing the quantitative metrics for a more comprehensive evaluation.

Figure 5.

Spectrogram comparisons of speech signals corrupted by cafe noise at (top) 12.5 dB and (bottom) 2.5 dB SNR. Each panel displays (a) clean speech, (b) noisy mixture, (c) enhancement by the baseline MUSE model, and (d) enhancement by the proposed MUSE++ model.

Each panel consists of four subfigures: (a) clean reference speech, (b) noisy input, (c) output enhanced by MUSE, and (d) output enhanced by MUSE++. At 12.5 dB SNR, the noisy input exhibits substantial background artifacts and spectral blurring. MUSE suppresses much of the noise and partially restores speech harmonics, although remnants of blurring remain. By contrast, MUSE++ produces cleaner backgrounds and crisper harmonic contours, more closely matching the clean reference.

At the lower 2.5 dB SNR, where noise severely impairs the signal, both models are challenged. MUSE recovers primary speech bands but leaves notable residual noise, particularly in unvoiced regions. MUSE++ achieves even greater noise suppression, yielding a spectrogram that more faithfully reflects the temporal and spectral patterns of the clean signal—even under these adverse conditions.

Given the comparable SE metric scores for MUSE and MUSE++, the spectrograms do not always reveal stark visual differences between the two approaches. Nevertheless, MUSE++ typically demonstrates superior background noise suppression. However, this comes at a cost: occasional over-suppression leads to the unintended removal of low-energy speech components. Addressing this tendency, and improving the retention of weak speech features, remains a key direction for future model refinement.

5.5. Comparison with Some State-of-the-Art SE Methods

Table 6 presents the PESQ and STOI scores, as well as additional perceptual metrics, for the proposed MUSE++ framework and several state-of-the-art (SOTA) lightweight SE models, including the backbone model MUSE [7], TSTNN [39], DB-AIAT [40], DPT-FSNet [41], MetricGAN-OKDv2 [42], and MANNER-S-5.3GF [43]. Notably, the results for these comparative methods are primarily compiled from [7].

Table 6.

The SE performance scores (rounded to the nearest two decimal places) of the presented MUSE++ variants and several SOTA lightweight SE frameworks, including TSTNN [39], DB-AIAT [40], DPT-FSNet [41], MetricGAN-OKDv2 [42], MANNER-S-5.3GF [43], and MUSE [7] (reported and reproduced).

From this table, several key observations can be drawn:

- The proposed MUSE++ framework consistently delivers competitive or superior performance across all evaluated metrics (PESQ, CSIG, CBAK, COVL, STOI) while maintaining a markedly lower parameter count ( M) than do all the other baseline models.

- Specifically, MUSE++ achieves the highest scores for CSIG (), CBAK (), and COVL (), outperforming the results of MUSE, as well as more parameter-intensive models such as DB-AIAT ( M), DPT-FSNet ( M), and MetricGAN-OKDv2 ( M).

- MUSE++ also yields highly competitive PESQ () and STOI () scores, closely matching or equaling the best-performing methods, including MUSE and DPT-FSNet, but with significantly reduced computational demands and memory usage.

- In comparison with the backbone MUSE model ( M), MUSE++ reduces the model size by approximately while attaining comparable or improved perceptual and intelligibility scores. This result underscores the efficiency and effectiveness of the architectural improvements integrated into MUSE++.

- Other SOTA lightweight models such as TSTNN, DB-AIAT, DPT-FSNet, MetricGAN-OKDv2, and MANNER-S-5.3GF, despite their substantially larger parameter counts, do not consistently surpass MUSE++ in either qualitative or quantitative performance metrics.

Collectively, these results demonstrate that MUSE++ achieves an excellent trade-off between compactness and enhancement quality, rendering it particularly suitable for resource-constrained and real-time SE applications.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

In this work, we propose MUSE++: an enhanced speech enhancement framework that builds upon and advances the original MUSE architecture through extended loss function and the integration of a Mamba-based state-space model. Our method introduces a combination of dynamic SNR-based data augmentation and a multi-objective loss formulation, which together enable robust feature extraction and improved generalization to diverse acoustic conditions. Comprehensive experiments on the VoiceBank-DEMAND dataset demonstrate that MUSE++ achieves competitive or superior enhancement performance across key metrics—including PESQ, CSIG, CBAK, COVL, and STOI—while dramatically reducing model complexity and parameter count. Compared with the original MUSE and other state-of-the-art lightweight models, MUSE++ attains an optimal balance between efficiency, compactness, and SE quality.

A primary goal of this work is to enable practical, real-world deployment. The lightweight design, reduced computational requirements, and consistently strong performance make MUSE++ particularly suitable for use on mobile devices, hearing aids, smart assistants, Internet of Things (IoT) platforms, and other resource-constrained or real-time applications. Such deployability ensures that high-quality SE is accessible in everyday scenarios, even under challenging acoustic environments.

Despite these advances, several open challenges remain. First, future studies are needed to investigate more sophisticated data augmentation techniques, particularly those that address non-stationary real-world noise and multi-microphone scenarios. Second, extending our approach to multi-modal settings—such as audio–visual or bone-conduction fusion—may further enhance robustness in extreme environments. Third, a deeper exploration of diverse loss functions and unsupervised or self-supervised learning frameworks could drive further improvements in model generalization and perceptual quality. Additionally, while our dynamic SNR augmentation strategy matches the VoiceBank-DEMAND training protocol, we did not perform ablation studies on different SNR ranges or noise categories in this work due to resource limitations. In the future, we aim to systematically analyze these factors and evaluate the proposed method on larger SE corpora and more challenging acoustic environments.

In summary, MUSE++ establishes a robust foundation for lightweight and effective SE, with a clear focus on real-world deployment. Future research will expand its applicability to broader acoustic and deployment scenarios, integrate additional modalities, and further refine the training strategies to improve both performance and practical utility.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.-J.L. and J.-W.H.; methodology, T.-J.L. and J.-W.H.; software, T.-J.L.; validation, T.-J.L. and J.-W.H.; formal analysis, J.-W.H. and T.-J.L.; investigation, J.-W.H.; resources, J.-W.H.; data curation, J.-W.H. and T.-J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-W.H.; writing—review and editing, J.-W.H.; visualization, J.-W.H. and T.-J.L.; supervision, J.-W.H.; project administration, J.-W.H.; funding acquisition, J.-W.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Leglaive, S.; Fraticelli, M.; ElGhazaly, H.; Borne, L.; Sadeghi, M.; Wisdom, S.; Pariente, M.; Hershey, J.R.; Pressnitzer, D.; Barker, J.P. Objective and subjective evaluation of speech enhancement methods in the UDASE task of the 7th CHiME challenge. Comput. Speech Lang. 2025, 89, 101685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.Y.; Xia, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Weng, C. Sixty Years of Frequency-Domain Monaural Speech Enhancement. Sensors 2023, 23, 9386. [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan, S. Deep neural networks for speech enhancement and recognition: A systematic review. J. Speech Lang. Technol. 2025, 27, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boll, S.F. Suppression of acoustic noise in speech using spectral subtraction. IEEE Trans. Acoust. Speech Signal Process. 1979, 27, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ephraim, Y.; Malah, D. Speech enhancement using a minimum mean-square error log-spectral amplitude estimator. IEEE Trans. Acoust. Speech Signal Process. 1984, 33, 443–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliwal, K.K.; Wojcicki, K.; Rao, B.P. The importance of phase in speech enhancement. Speech Commun. 2010, 53, 465–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, J. MUSE: Flexible Voiceprint Receptive Fields and Multi-Path Fusion Enhanced Taylor Transformer for U-Net-based Speech Enhancement. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2406.04589. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, X.; Wang, D.; Hu, Y.; Zhu, C.; Chen, K.; Lu, J. UL-UNAS: Ultra-Lightweight U-Nets for Real-Time Speech Enhancement via Network Architecture Search. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2503.00340. [Google Scholar]

- Wahab, F.E.; Saleem, N.; Dhahbi, S. Compact deep neural networks for real-time speech enhancement: A review. J. Signal Process. 2024, 110, 105264. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, N.; Bourouis, S.; Elmannai, H.; Algarni, A.D. CTSE-Net: Resource-efficient convolutional and TF-transformer network for speech enhancement. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 290, 110597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhuang, X.; Qian, Y.; Wang, M. Lightweight Dynamic Sparse Transformer for Monaural Speech Enhancement. In Proceedings of the Interspeech 2024, Kos Island, Greece, 1–5 September 2024; pp. 3816–3820. [Google Scholar]

- Mattursun, D.; Wu, Y.; Wang, S.; Qian, Y. Magnitude-Phase Dual-Path Speech Enhancement Network. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.21571. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, W.; Sun, M.; Xia, Y.; Wang, W. Supervised-learning-based neural Kalman filter for speech enhancement. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.13962. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, D.; Huang, J.; Wu, Y.; Zou, Y.; Xue, W.; Jin, Z.Y.; Zhang, S.; Wu, J.; Yu, D. PHASEN: A self-supervised phase-and-harmonics-aware speech enhancement network. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; Volume 34, pp. 9458–9465. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.X.; Ai, Y.; Ling, Z.H. MP-SENet: A Speech Enhancement Model with Parallel Denoising of Magnitude and Phase Spectra. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.13686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.X.; Ai, Y.; Ling, Z.H. Explicit estimation of magnitude and phase spectra in speech enhancement. Neural Netw. 2025, 189, 107562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, J. Mixed T-domain and TF-domain Magnitude and Phase Methods for Robust Speech Enhancement. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 68708. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Liu, W.; Meng, R.; Lee, G.; Baek, S.; Moon, H.G. Fspen: An Ultra-Lightweight Network for Real Time Speech Enahncment. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024—2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 14–19 April 2024; pp. 10671–10675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, S. LiSenNet: Lightweight Speech Enhancement Network with Sub-Band Feature Capture. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.13051. [Google Scholar]

- Dhahbi, S.; Saleem, N.; Gunawan, T.S.; Bourouis, S.; Ali, I.; Trigui, A.; Algarni, A.D. Lightweight Real-Time Recurrent Models for Speech Enhancement and Automatic Speech Recognition. Int. J. Interact. Multimed. Artif. Intell. 2024, 8, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelsanti, D.; Tan, Z.H.; Xu, Y.; Richter, S.R.; Ma, M.; Sørensen, J.; Jensen, J.; Gerkmann, T.; Jensen, S.; Virtanen, T.; et al. An Overview of Deep-Learning-Based Audio-Visual Speech Enhancement and Separation. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2021, 29, 1368–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X. Lip landmark-based audio-visual speech enhancement with multimodal feature fusion network. Neurocomputing 2023, 549, 126432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, L. A lightweight speech enhancement network fusing bone-conduction and air-conduction features. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2024, 156, 1355–1368. [Google Scholar]

- Wahab, F.E.; Dhahbi, S.; Bourouis, S. MA-Net: Resource-efficient multi-attentional network for end-to-end speech enhancement. Neurocomputing 2024, 557, 129150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Zhao, H.; Meng, W.; Wang, Y. One-shot motion talking head generation with audio-driven model. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 297, 129344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Jiang, H.; Liu, D.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, J.; Dustdar, S. Combining IMU With Acoustics for Head Motion Tracking Leveraging Wireless Earphone. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2024, 23, 6835–6847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, A.; Dao, T. Linear-Time Sequence Modeling with Selective State Spaces. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.00752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, T.; Gu, A. Transformers are SSMs: Generalized models and efficient algorithms through structured state space duality. In Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning, Vienna, Austria, 21–27 July 2024; ICML’24. [Google Scholar]

- Choromanski, K.; Likhosherstov, V.; Dohan, D.; Song, X.; Gane, A.; Sarlos, T.; Hawkins, P.; Davis, J.; Mohiuddin, A.; Kaiser, L.; et al. Rethinking Attention with Performers. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.14794. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Li, B.Z.; Khabsa, M.; Fang, H.; Ma, H. Linformer: Self-Attention with Linear Complexity. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.04768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, H.; Xiao, T.; Qian, X.; Ahmed, B.; Ambikairajah, E.; Li, H.; Epps, J. Mamba in Speech: Towards an Alternative to Self-Attention. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.12609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, T.G.; Chun, C.J. Mamba-based Hybrid Model for Speech Enhancement. In Proceedings of the Interspeech, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 17–21 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Valentini-Botinhao, C.; Wang, X.; Takaki, S.; Yamagishi, J. Investigating RNN-based speech enhancement methods for noise-robust Text-to-Speech. In Proceedings of the 9th ISCA Workshop on Speech Synthesis Workshop (SSW 9), Sunnyvale, CA, USA, 13–15 September 2016; pp. 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiemann, J.; Ito, N.; Vincent, E. The Diverse Environments Multi-channel Acoustic Noise Database (DEMAND): A database of multichannel environmental noise recordings. In Proceedings of the 21st International Congress on Acoustics, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2–7 June 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, C.K.; Gopal, V.; Cutler, R.; Beyrami, E.; Cheng, R.; Dubey, H.; Matusevych, S.; Aichner, R.; Aazami, A.; Braun, S.; et al. The INTERSPEECH 2020 Deep Noise Suppression Challenge: Datasets, Subjective Testing Framework, and Challenge Results. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.13981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITU-T. Perceptual Evaluation of Speech Quality (PESQ), an Objective Method for End-to-End Speech Quality Assessment of Narrowband Telephone Networks and Speech Codecs; Technical Report P.862; International Telecommunication Union: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Taal, C.H.; Hendriks, R.C.; Heusdens, R.; Jensen, J. An Algorithm for Intelligibility Prediction of Time–Frequency Weighted Noisy Speech. IEEE Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2011, 19, 2125–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Loizou, P.C. Evaluation of Objective Quality Measures for Speech Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2008, 16, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; He, B.; Zhu, W.P. TSTNN: Two-stage Transformer Based Neural Network for Speech Enhancement in the Time Domain. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2021—2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Toronto, ON, Canada, 6–11 June 2021; pp. 7098–7102. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, G.; Li, A.; Zheng, C.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H. Dual-Branch Attention-In-Attention Transformer for Single-Channel Speech Enhancement. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Singapore, 22–27 May 2022; pp. 7847–7851. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, F.; Chen, H.; Zhang, P. DPT-FSNet: Dual-Path Transformer Based Full-Band and Sub-Band Fusion Network for Speech Enhancement. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Singapore, 22–27 May 2022; pp. 6857–6861. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, W.; Lee, B.H.; Kim, J.S.; Park, H.J.; Han, S.W. MetricGAN-OKD: Multi-Metric Optimization of MetricGAN via Online Knowledge Distillation for Speech Enhancement. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 31521–31538. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, W.; Park, H.J.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, B.H.; Han, S.W. Multi-View Attention Transfer for Efficient Speech Enhancement. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.10367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).