Abstract

This work investigates the dynamical properties of the Kolmogorov–Petrovskii–Piskunov (KPP) equation. We begin by establishing its non-integrability through the Painlevé test. Using a traveling wave transformation, we reduce the equation to a planar dynamical system, which we identify as non-conservative. A subsequent bifurcation analysis, supported by Bendixson’s criterion, rules out the existence of periodic orbits and, thus, periodic solutions—a finding further validated by phase portraits. Furthermore, we classify the types and co-dimensions of the bifurcations present in the system. We demonstrate that under certain conditions, the system can exhibit saddle-node, transcritical, and pitchfork bifurcations, while Hopf and Bogdanov–Takens bifurcations cannot occur. This study concludes by systematically deriving a power series solution for the reduced equation.

MSC:

35C07; 35C08; 37K40; 83C15

1. Introduction

The combination of mathematical modeling with experimental biology has profoundly advanced our understanding of complex biological phenomena in recent decades. These models, grounded in empirical data, formally describe the components, architecture, and interactive processes of a system. They are not merely descriptive but predictive tools that allow for the simulation of scenarios, the extension of biological theory, and the formulation of novel hypotheses. The quantitative power of this approach is evidenced by its applications in solving real-world problems, such as predicting outcomes precisely prior to action being taken, and so on [1,2]. In recent years, researchers in mathematics and physics have shown growing interest in exploring the fundamental characteristics of bacterial cells, which are essential to sustaining all animal life on Earth. Their investigations often rely on theoretical frameworks, mathematical modeling, and abstract representations of biological systems to understand bacterial morphology, growth dynamics, and behavioral patterns. Bacteria constitute a vast group of proteolytic microorganisms, typically measuring only a few micrometers and exhibiting diverse shapes, such as spherical, rod-like, and spiral forms. Recognized as among the earliest life forms to emerge on the planet, bacteria thrive in extreme environments—including radioactive waste, subterranean layers of the Earth’s crust, soil, aquatic habitats, and acidic thermal springs. Despite their ubiquity, only about of bacterial species are cultivable under laboratory conditions, a small fraction compared to the estimated global population of approximately cells. The scientific discipline dedicated to understanding bacterial biology and its implications for human life is known as bacteriology [3,4,5].

The growing capacity to model complex natural systems represents a significant advance in nonlinear science. This progress is largely driven by the application of nonlinear differential equations, which provide the essential mathematical framework for phenomena across disciplines such as biology, fluid dynamics, and the physical sciences. As a result, these equations are a central focus of contemporary theoretical and applied research [6,7,8,9]. This study is devoted to the analysis of nonlinear partial differential equations (NLPDEs), which are pivotal in modeling a broad spectrum of complex phenomena. Consequently, the pursuit of exact solutions for these equations has emerged as a central and dynamic area of research. A principal objective in this field is the derivation of such solutions, particularly solitary wave and traveling wave solutions, to gain deeper insight into the underlying systems. To this end, a diverse suite of analytical techniques have been developed and applied to various NLPDE models. Notable methods cited in the literature include the generalized exponential rational function method [10] and the generalized Kudryashov method [11,12]. The analytical toolkit is further enriched by techniques such as the improved simple equation method, the modified F-expansion method [13], the exp-function method [14], the modified Jacobi elliptic function expansion method [15], Painlevé analysis [16,17,18], Hirota’s method [19,20], auto-Bäcklund transformations [21,22,23], and bifurcation methods [24,25,26].

We consider the nonlinear KPP equation:

where , and are real-valued parameters, the subscripts represent the partial derivatives, and represents the state variable in a spatiotemporal domain. Originally introduced by the Russian mathematicians Kolmogorov, Petrovsky, and Piskunov in 1937 [27,28], the KPP equation provides a foundational framework for modeling a wide array of phenomena in population dynamics, chemical kinetics, and physics. The KPP equation has been the subject of extensive research, with numerous studies addressing it from various perspectives. The existing literature reveals a rich tapestry of analytical and numerical techniques applied to this model. For instance, several studies have focused on deriving exact solutions. The generalized Kudryashov method was employed in [29] to obtain general solutions, all of which were expressed in exponential form. Similarly, Ref. [30] constructed exact solutions by combining the Riccati equation method with a generalized extended -expansion, while [31] utilized a modified sub-equation method for the same purpose. Other analytical approaches include the -expansion method applied in [32] for traveling wave solutions and the simple equation technique used in [33] to obtain time-dependent variable solitons. On the numerical front, diverse schemes have been developed. The work in [34] introduced a novel algorithm based on Adams–Bashforth extrapolation, reporting superior efficiency over traditional methods. Furthermore, Ref. [35] applied a hybrid approach, using the generalized Sinh–Gordon equation method alongside B-spline schemes to acquire numerical solutions. Approximate analytical oscillatory solutions for a generalized KPP equation were also discussed in [36] using dynamical systems theory and a hypothesis undetermined method. The framework of the KPP equation has also been extended in several directions. A prominent area of research involves its generalization through fractional derivatives, applied to either spatial or temporal coordinates, or both. Within this context, the homotopy perturbation method was used in [37] to find approximate solutions for the fractional KPP equation, and the modified extended direct algebraic method was applied in [38] to construct propagating soliton solutions for this fractional variant. Another significant extension incorporates random effects by adding stochastic perturbation terms.

The significance of the KPP Equation (1) is further underscored by its role as a unifying framework for several seminal models. Specific parameter choices recover well-known equations: for instance, the Fitzhugh–Nagumo equation for nerve impulse transmission is obtained with and (), where represents the electric potential [39,40]. Similarly, the Fisher equation, describing the spread of an advantageous gene ( being its density), results from the parameters , , and [41,42]. Furthermore, the Huxley equation, which models cross-bridge dynamics in muscle physiology, corresponds to the case where and with [43].

Despite the KPP equation’s significance in modeling numerous phenomena, a comprehensive analysis of its integrability and bifurcation behavior remains absent from the literature, a gap that this work aims to address.

The remainder of this work is structured as follows: The integrability of the KPP equation is analyzed in Section 2 using Painlevé analysis. Bifurcation analysis and phase portraits are conducted in Section 3. Section 4 involves a proof of the non-existence of periodic solutions for the KPP equation and derives a series solution. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the results of the study.

2. Integrability Analysis

The integrability of the governing equation (Equation (1)) is investigated here by assessing its Painlevé property. This is accomplished through a singularity analysis based on the ARS algorithm, which is summarized in Appendix A to ensure a self-contained presentation. The fundamental question addressed is whether all possible solutions exhibit single-valued expansion about any movable singularity manifold.

We consider a solution expansion in the neighborhood of a non-characteristic singular manifold ():

where is a negative integer and the coefficients are analytic near , with .

Leading-Order Analysis: The dominant behavior emerges from the leading term:

Substituting Expression (3) into Equation (1) reveals that the most singular terms balance when . The leading coefficient follows from the terms:

Resonance Analysis: The positions where arbitrary functions may enter Series (2) are identified by substituting

and collecting terms yields the resonance condition:

The functions are arbitrary if −1, 4 which are named the resonances. The value is the only acceptable resonance corresponding to the free location of the singularity manifold itself, while suggests possible arbitrariness at the fifth term in Series (2).

Verification of Compatibility Conditions: To validate the Painlevé property, we examine whether sufficient arbitrariness exists at the resonance positions. Substituting the finite expansion

into Equation (1) generates determining equations for the coefficients by examining different powers of :

Power : Confirms the leading coefficient (Equation (4)).

Power : Determines the coefficient as follows:

Power : Yields the second coefficient:

Power : Provides the third coefficient:

Power (Resonance ): The condition at the resonance produces

Substitution of the known coefficients – into Equation (11) demonstrates that cannot be chosen arbitrarily—the compatibility condition fails at the resonance .

The failure to satisfy the necessary condition at resonance establishes that Equation (1) lacks the Painlevé property, leading to the following theorem:

Theorem 1.

Equation (1) does not possess the Painlevé property and is therefore non-integrable in the Painlevé sense.

3. Bifurcation Analysis

The non-integrability of Equation (1) immediately implies that it cannot be solved using standard integrability-based techniques, such as the inverse scattering transform or soliton theory, which are characteristic of integrable PDEs. Non-integrable PDEs are typically nonlinear and present a greater challenge for analytical solution. They generally do not possess explicit analytic solutions or an infinite set of conserved quantities [44]. Consequently, researchers typically rely on approximate, numerical, or perturbative methods for their study. Furthermore, a dynamical systems approach can be effectively employed to gain qualitative insights into the nature of their solutions.

This section aims to employ the dynamical systems framework to conduct a qualitative examination of the solutions to Equation (1). We consider solutions of the KPP Equation (1) in the form of

where is a real-valued function, a is a non-zero constant representing the wave number, and is the wave variable. Substituting this form of Equation (12) into Equation (1), it simplifies to an ODE. Consequently, the resulting equation is

where ′ indicates the derivative with respect to . This section endeavors to explore some dynamical aspects to Equation (1). The qualitative theory for planar integrable systems [45] is applied to analyze Equation (13), which is equivalent to the dynamical system

The dynamical system (14) is non-conservative, since . To be more precise, it is chaotic because is always negative. The equilibrium states of (14) are given by the points , where represents the real solutions of the cubic equation

On the other hand, to determine the nature of the equilibrium points, we consider that the linearized system of (14) with respect to the equilibrium point is

Here, and denote the perturbed variables, and represents the coefficient matrix of the linearized system (16). More precisely, it corresponds to the Jacobian matrix of the nonlinear system (14) evaluated at the equilibrium point . The associated eigenvalues are given by

where

The stability of the equilibrium point is detected by evaluating the magnitude and sign of the eigenvalues derived from Equation (17). In particular, the point is deemed stable if both eigenvalues have negative real parts, unstable when at least one exhibits a positive real part, and neutrally stable if the real parts of both eigenvalues vanish. Moreover, a broader classification of the equilibrium behavior can be established based on the qualitative nature of the eigenvalues; for further discussion, refer to [45].

The bifurcation structure and phase portrait of the planar dynamical system (14) are analyzed with respect to the parameters , and . To begin, we identify the system’s equilibrium points by introducing the discriminant . The number of these equilibrium points is governed by the sign of : whether it is negative, zero, or positive. Accordingly, each case is examined separately to capture the distinct dynamical behaviors that emerge.

Case A: If , which is equivalent to with , then Equation (15) admits a unique real solution, namely, . Consequently, the point serves as the sole equilibrium of the system described by Equation (14). To detect the nature of the equilibrium point , we compute the eigenvalues (17) at and obtain

Since , the parameters and own the same sign. This leads to the following possible scenarios:

- (a)

- If , then the eigenvalues are real and satisfy the inequality . This configuration indicates that the equilibrium point is a saddle point, exhibiting hyperbolic behavior. Since one of the eigenvalues is positive, the equilibrium is inherently unstable. The corresponding phase portrait is illustrated in Figure 1a.

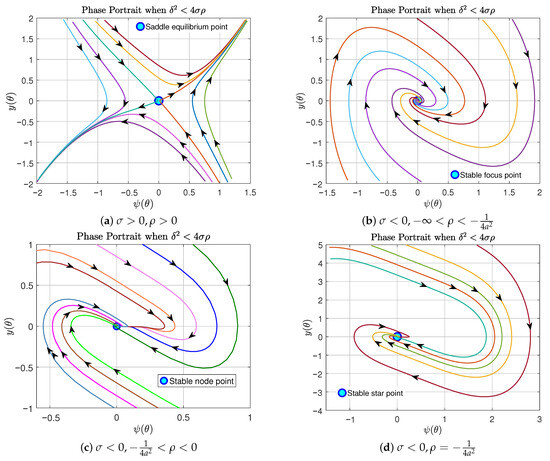

Figure 1. Phase portrait of system (14) corresponding to the case .

Figure 1. Phase portrait of system (14) corresponding to the case . - (b)

- (c)

- For , the eigenvalues are real and strictly negative, satisfying . This configuration implies that the equilibrium point is a stable node. The associated phase portrait is presented in Figure 1c.

- (d)

- Finally, when , the eigenvalues coincide and are strictly negative, given by . This configuration characterizes the equilibrium point as a stable star. The corresponding phase portrait is illustrated in Figure 1d.

We summarize the nature of the equilibrium point in Table 1.

Table 1.

The nature of the equilibrium point if and .

Case B: If , which implies provided that , then Equation (15) admits two real-valued solutions: and . As a result, the planar dynamical system (14) possess two equilibrium points: and . To assort the nature of these points, we compute the eigenvalues (19) at them. We find

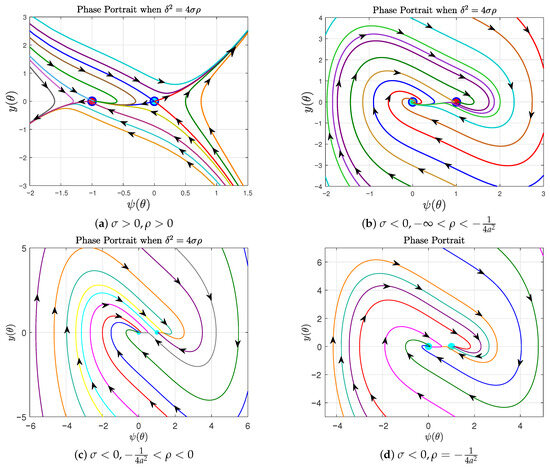

The equilibrium is non-hyperbolic, possessing one zero and one negative eigenvalue, which commonly indicates a saddle-node type. The behavior of , on the other hand, depends on the parameter , and its type is exactly as described in Table 1. Table 2 summarizes the nature of these equilibrium points and the corresponding phase portraits.

Table 2.

Classifications of the equilibrium points if and .

Table 2.

Classifications of the equilibrium points if and .

| No. | Sign of | Classification of | Figure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | + | + | Saddle point | Saddle node | Figure 2a |

| 2. | − | Stable focus | Figure 2b | ||

| 3. | − | Stable node | Figure 2c | ||

| 4. | − | Stable star | Figure 2d | ||

Case C: When , corresponding to the condition , Equation (15) yields two distinct real solutions: and . Accordingly, the planar dynamical system Equation (14) possesses two equilibrium points: and . To explore the nature of these equilibrium points, we compute the eigenvalues (19) at them. We find

Consequently, two distinct regimes arise when , corresponding to either or . Additionally, in the case where , the inequality holds automatically. Let us consider these scenarios, separately:

Figure 2.

Phase portrait of system (14) corresponding to the case .

I. We analyze the case in which provided that .

- (a)

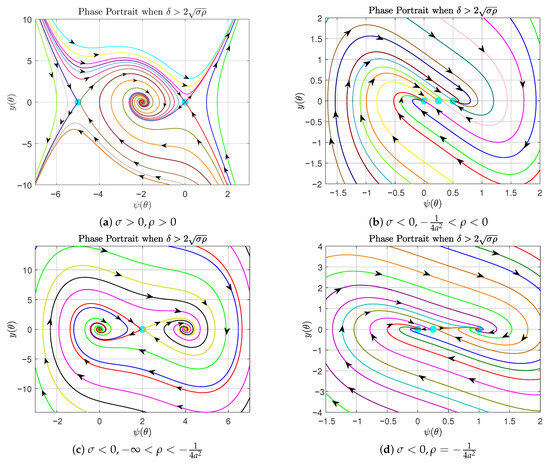

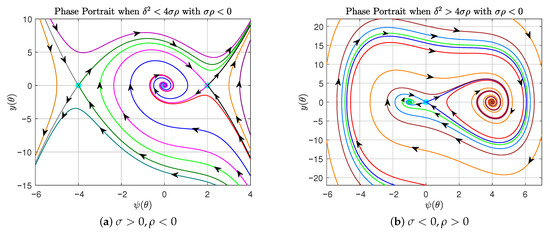

- When , the eigenvalues are real and satisfy , indicating that the equilibrium points and are saddle points with hyperbolic character. In contrast, the eigenvalues are complex with negative real parts, signifying that is a stable focus or stable spiral point. The corresponding phase portrait is depicted in Figure 3a.

Figure 3. Phase portrait of system (14) corresponding to the case .

Figure 3. Phase portrait of system (14) corresponding to the case . - (b)

- (c)

- When , the eigenvalues and are complex with negative real parts, indicating that the equilibrium points and are stable foci (stable spiral points). In contrast, the eigenvalues are real and satisfy , which implies that is a saddle point with hyperbolic character. The corresponding phase portrait for this configuration is illustrated in Figure 3c.

- (d)

- When , the equilibrium points exhibit distinct stability properties. , with a repeated negative eigenvalue , is a stable star. is a stable spiral, as its eigenvalues are complex with a negative real part. In contrast, is a saddle point (hyperbolic equilibrium point) because its real eigenvalues satisfy . This configuration is illustrated in the phase portrait of Figure 4d.

Figure 4. Phase portrait of system (14) corresponding to the case with .

Figure 4. Phase portrait of system (14) corresponding to the case with .

The dynamical system (14) exhibits a qualitatively similar phase portrait under the condition with . Thus, we introduce a summary of these results without details in Table 3.

Table 3.

Classifications of the equilibrium points if and .

II. Our analysis now turns to the regime where . In this regime, the condition is automatically satisfied, leading to two distinct possibilities:

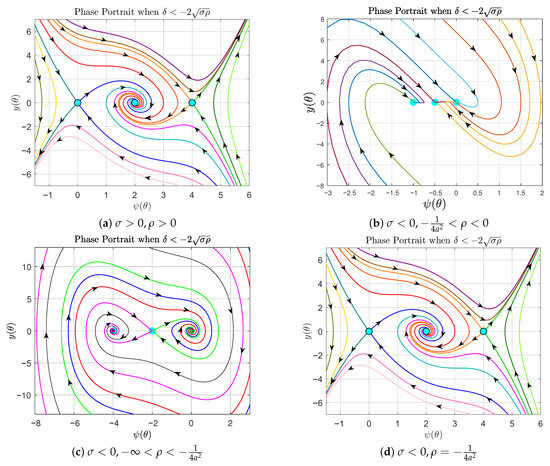

- (a)

- For the parameter region , the eigenvalues at form a complex conjugate pair with a negative real part, while the eigenvalues at and are real and satisfy . Consequently, is a stable focus, and and are both saddle points (hyperbolic equilibria). The corresponding phase portrait is shown in Figure 5a.

Figure 5. Phase portrait of system (14) corresponding to the case with .

Figure 5. Phase portrait of system (14) corresponding to the case with . - (b)

- When , the equilibrium point is a saddle, as indicated by its real eigenvalues . In contrast, and are stable foci, characterized by complex eigenvalues with negative real parts. This behavior is illustrated in the phase portrait of Figure 5b.

We now summarize the types and co-dimensions of the bifurcations occurring in system (14). For a more detailed explanation, please refer to Appendix B.

4. Solutions

While numerous studies have focused on constructing specific solutions to Equation (1)—particularly traveling wave solutions—these have predominantly yielded non-periodic forms. This observation prompts a fundamental question: does Equation (1) admit any periodic solutions? To address this, we employ Bendixson’s criterion [23]. This theorem states that the dynamical system does not have any closed orbit if its divergence does not vanish in a simply connected zone D.

We proceed by computing the divergence of the dynamical system (14):

This divergence is a negative constant, and consequently, it is neither zero nor changes sign anywhere in the plane. Since is simply connected, Bendixson’s criterion directly precludes the existence of periodic orbits in the entire phase plane. This conclusion is further corroborated by phase portrait analysis, as illustrated in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5. We thus establish the following theorem:

Theorem 2.

Given the absence of periodic solutions, we turn to numerical and approximate analytical techniques. In the subsequent subsection, we develop a series solution for Equation (1) using a power series expansion approach, drawing inspiration from the methodology presented in [46].

Series Solution

We begin by postulating a power series solution for Equation (13) of the form

where the coefficients are to be determined. The necessary derivatives and nonlinear terms are given by

Substituting the expressions from (23) and (24) into Equation (13) yields

To satisfy this identity for all , we equate the coefficients for each power of , leading to the following recurrence relations: For ,

For , the general recurrence relation is

Consequently, the power series solution to Equation (13)—and, hence, to Equation (1)—is given by

where and are arbitrary constants, and the subsequent coefficients are generated recursively from Equation (27).

5. Conclusions

This study presents a detailed investigation of the KPP equation, which serves as a mathematical model for various phenomena observed in biological and chemical systems. The research addresses several aspects that have not been thoroughly examined in the existing literature. Specifically, the integrability characteristics of the KPP equation were investigated through Painlevé analysis, employing the well-established ARS algorithm. The results demonstrate that the KPP equation does not possess the Painlevé property, thereby establishing its non-integrability within the Painlevé framework. This finding further suggests that the equation may exhibit intricate and chaotic dynamical behavior. The non-integrability of Equation (1) immediately implies that it cannot be solved using standard integrability-based techniques, such as the inverse scattering transform or soliton theory, which are characteristic of integrable PDEs. It generally does not possess explicit analytic solutions or an infinite set of conserved quantities. Consequently, a dynamical systems approach can be effectively employed to gain qualitative insights into the nature of their solutions. We assume that the KPP Equation (1) has a solution in the form (12), which is utilized to transform the original -dimensional partial differential equation into a second-order ordinary differential equation, which can be interpreted as a two-dimensional non-conservative autonomous dynamical system in the phase plane. We conducted a comprehensive bifurcation analysis of the reduced system, revealing diverse dynamical structures. The existence and stability characteristics of equilibrium points depend fundamentally on the parameters , , and through the discriminant . By examining phase portraits corresponding to three distinct cases—, , and —we identified various equilibrium configurations, including saddle points, stable nodes, stable foci, and stable star nodes. This systematic classification enables a complete qualitative characterization of all admissible traveling wave solutions to the KPP equation. Furthermore, we classified the types and co-dimensions of the bifurcations present in the system. We demonstrated that under certain conditions, the system can exhibit saddle-node, transcritical, and pitchfork bifurcations, while Hopf and Bogdanov–Takens bifurcations cannot occur. This is completely proven in Appendix B and tabulated in Table 4.

Table 4.

Complete bifurcation classification with co-dimensions.

An important theoretical result established in this study is the absence of periodic orbits in the reduced dynamical system, which we proved rigorously using the Bendixson criterion (Theorem 2). Since the divergence of the vector field remains uniformly negative throughout the simply connected domain , no closed trajectories can exist. This analytical finding is further supported by our detailed examination of the phase portraits, which consistently exhibit no periodic behavior across all parameter regimes. Given the established non-integrability and the proven absence of periodic orbits, we pursued an alternative approach by developing approximate analytical solutions through power series expansion. We derived a recurrence relation that determines the series coefficients systematically, offering a computationally tractable framework for constructing solutions parameterized by two arbitrary constants, and .

In summary, we conducted a detailed multi-perspective study of the KPP equation. The demonstrated non-integrability, characterized bifurcation dynamics, and proven absence of periodic solutions collectively deepen our theoretical insight into this well-known model. The power series technique developed herein also offers a practical means for approximating solutions. These contributions bridge existing gaps in the literature and provide a platform for future work, potentially including numerical bifurcation studies, extensions to fractional-order or stochastic frameworks, and investigations of chaotic dynamics in higher dimensions.

Funding

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [Grant No. KFU253612].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Painlevé Analysis

This appendix outlines the Painlevé test for integrability analysis. It is applied to a general NLPDE of the form

where is a polynomial function in u and its partial derivatives, and u is a complex-valued function of the real variables x and t. The Painlevé analysis provides a systematic criterion for identifying integrable nonlinear systems by examining the singularity structure of their solutions. The central concept is the Painlevé property, which requires that all solutions of a PDE be single-valued around any movable singularity—a singularity whose position depends on initial or boundary conditions. This approach, with roots in the work of Kowalevskaya on rigid-body dynamics [47], and later extended by Painlevé and others, was formalized for PDEs through the algorithmic procedure developed by Ablowitz, Ramani, and Segur [44,48]. The following steps summarize the application of the ARS algorithm to Equation (A1):

The analysis begins with a Laurent-series ansatz for the solution in the neighborhood of a movable singular manifold :

where is a negative integer and .

Step 1: Leading-Order Analysis

To determine the leading-order exponent and coefficient , we substitute the dominant form

into the governing PDE (A1). Balancing the most singular terms yields the value of and, subsequently, an algebraic equation for .

Step 2: Determination of Resonances

Resonances (p) are the powers in the Laurent series at which arbitrary functions may appear. They are found by substituting the perturbation

into (A1) and keeping the terms linear in . The condition for a non-trivial produces an eigenvalue problem whose solutions are the resonances. The resonance , corresponding to the arbitrary location of the singular manifold, is always present. A necessary condition for the Painlevé property is that all other resonances are non-negative integers.

Step 3: Verification of Compatibility Conditions

The final step involves verifying the consistency of the Laurent series at each resonance. The truncated expansion

where is the largest resonance, is substituted into (A1). At each resonance p, the corresponding coefficient must be an arbitrary function, or the equation for must be identically satisfied. If this holds for all resonances, the PDE passes the Painlevé test and is deemed integrable in the Painlevé sense.

Appendix B. Complete Bifurcation Classification and Co-Dimension

This appendix presents a comprehensive bifurcation classification and co-dimension analysis for the dynamical system (14). For an in-depth discussion of these concepts, the reader is referred to [49]. In the following, we prove the main theorems related to this analysis.

Appendix B.1. Saddle-Node Bifurcation (Co-Dimension 1)

Theorem A1.

A saddle-node bifurcation occurs in the system (14) under the condition , provided that .

Proof.

The necessary condition for a saddle-node bifurcation is the presence of a non-hyperbolic equilibrium with a zero eigenvalue, which is equivalent to the vanishing of the Jacobian determinant. Thus, Equation (18) gives

Simultaneously, the non-zero equilibrium point must satisfy Equation (15):

To find the parameter relationship that enables this bifurcation, we subtract (A7) from (A6), yielding

Excluding the trivial solution , we obtain the relevant equilibrium point at . Substituting this value into Equation (A7) gives

and, hence,

where refers to the critical bifurcation value. We now verify the non-degeneracy conditions. First, we analyze the local behavior near the bifurcation point, and then we translate the equilibrium to the origin by setting

where is very small. Inserting the expressions (A11) into the system (14) results in

where . By expanding g about the point and taking into account and , we obtain

Hence, the coefficient of the quadratic term in the normal form is

Second, we check the transversality condition

where w is left null eigenvectors of the Jacobian and

is a vector field corresponding to the system (14). After some calculations, we have

Both conditions (A14) and (A17) are met provided , which, along with to ensure that the equilibrium point is finite, completes the proof. □

Appendix B.2. Transcritical Bifurcation (Co-Dimension 1)

Theorem A2.

The system (14) undergoes a transcritical bifurcation when .

Proof.

A transcritical bifurcation occurs when two distinct equilibrium branches intersect and exchange stability [49]. To establish the occurrence of a transcritical bifurcation, we must verify the standard necessary and sufficient conditions at the bifurcation point.

Thus, the equilibria and intersect and exchange stability as the parameter passes through zero.The Jacobian matrix evaluated at the origin when is given by

This matrix has a zero determinant, , confirming that the origin is a non-hyperbolic equilibrium with a zero eigenvalue, as required.

Similar to Theorem A1, direct calculations show that the bifurcation is non-degenerate, since both the transversality condition and the non-vanishing quadratic term are satisfied. □

Appendix B.3. Pitchfork Bifurcation (Co-Dimension 2)

Theorem A3.

The system undergoes a pitchfork bifurcation at the equilibrium when the parameters satisfy and , provided the cubic coefficient is non-zero (). The bifurcation is supercritical if and subcritical if .

Proof.

To establish the occurrence of a pitchfork bifurcation, we must verify the necessary conditions: the existence of a symmetry, a non-hyperbolic equilibrium, and specific non-degeneracies.

First, setting simplifies the system (14) to

Let be the vector field. We observe that

This confirms that the system has the odd symmetry , a prerequisite for a pitchfork bifurcation.

Following Equation (15), the equilibrium points are the roots of the equation

This equation has the following solutions:

Thus, for , the system has either one or three fixed points due to the symmetry.

The bifurcation occurs when . At this point, the three fixed points merge into one at the origin: . The Jacobian matrix at the origin when is

This matrix has eigenvalues 0 and , confirming that the origin is a non-hyper-bolic equilibrium.

We now verify the non-degeneracy conditions. The first non-degeneracy condition requires a non-zero cubic coefficient in the dynamics restricted to the center manifold. For our system, this coefficient is . The condition ensures that the bifurcation is non-degenerate.

The second non-degeneracy condition is the transversality of the bifurcation parameter. We must check that the growth rate of the critical eigenvalue with respect to is non-zero. A calculation shows that at , confirming that the bifurcation unfolds generically.

The sign of the cubic coefficient determines the type of pitchfork bifurcation:

- If , the cubic term is stabilizing, and the two new symmetric branches that emerge for (or , depending on the sign of the transversality condition) are stable. This is a supercritical pitchfork bifurcation.

- If , the cubic term is destabilizing, and the two new symmetric branches are unstable. This is a subcritical pitchfork bifurcation.

The satisfaction of the symmetry, the merging of three equilibria, the zero eigenvalue, and the non-degeneracy conditions confirms that the system undergoes a pitchfork bifurcation at . □

Appendix B.4. Cusp Singularity (Co-Dimension 2)

Theorem A4.

The system has a cusp singularity at the origin in the parameter space, defined by and , provided the cubic coefficient is non-zero, .

Proof.

A cusp singularity is the organizing center for bifurcations of co-dimension 2, where both the first and second derivatives of the vector field (restricted to the center manifold) vanish. Our goal is to show that this happens at the point where the transcritical and pitchfork bifurcation conditions coincide.

Recall that the dynamics on the center manifold can be expressed in a reduced form as . The conditions for an equilibrium point to be non-hyperbolic are These conditions are satisfied at with parameters , as verified in the proofs for the transcritical and pitchfork bifurcations.

For a higher-order degeneracy, we must check the second derivative:

This confirms that the quadratic term also vanishes at the singularity. A point where is a candidate for a cusp.

The universal unfolding of this singularity, which captures all possible perturbed behaviors in a two-parameter neighborhood, is given by the normal form

where and serve as the unfolding parameters that perturb the system away from the singular point. The critical non-degeneracy condition is that the cubic coefficient is non-zero:

which holds if only and only if . This condition ensures that the singularity is of co-dimension 2 and is not more degenerate (e.g., of co-dimension 3). When , the two-parameter bifurcation diagram in the -plane features a curve of saddle-node bifurcations that meet at the cusp point () with a tangency. Within the cusp-shaped region, the system has three equilibrium points, and outside of it, only one.

Since all conditions for a cusp singularity are met—specifically, and at the origin—we can conclude that the system has a cusp singularity at , . □

Appendix B.5. Hopf Bifurcation

Theorem A5.

The system (14) cannot undergo a Hopf bifurcation for any values of its parameters.

Proof.

Recall that a Hopf bifurcation, which gives rise to limit cycles from an equilibrium point, requires two necessary conditions at the bifurcation point [49]:

- The trace of the Jacobian matrix must be zero ().

- The determinant of the Jacobian matrix must be positive ().

The first condition ensures a pair of purely imaginary eigenvalues, while the second ensures that the equilibrium is of a focus or center type (non-saddle) before the bifurcation.

Now, consider the general form of the system. The Jacobian matrix at any equilibrium point has a trace given by

Since the parameter is a positive constant related to the system’s inertia or damping, the trace is strictly negative for all parameter values and at all equilibria:

The failure of the first necessary condition () is sufficient to conclude that a Hopf bifurcation is impossible in this system. The constant, non-zero trace indicates that the real part of the eigenvalues can never cross the imaginary axis, which is the essential mechanism for a Hopf bifurcation. □

Theorem A6.

The system (14) cannot undergo a Bogdanov–Takens bifurcation for any values of its parameters.

Proof.

A Bogdanov–Takens bifurcation is a co-dimension 2 bifurcation that occurs when an equilibrium point has a Jacobian matrix with a double-zero eigenvalue (a nilpotent Jordan block of size 2) [49]. The necessary and sufficient linear algebra conditions for this are as follows:

- The trace of the Jacobian is zero: .

- The determinant of the Jacobian is zero: .

The first condition () ensures that the sum of the eigenvalues is zero, and the second () ensures that their product is zero, together implying that both eigenvalues are exactly zero.

Now, consider the Jacobian matrix J of the system. Its trace is given by

The parameter is a positive constant representing a time-scale or damping factor. Therefore, the trace is a strictly negative constant for all states and parameter values:

Since the first necessary condition for a Bogdanov–Takens bifurcation () is violated universally, it is impossible for the system to exhibit this bifurcation. The constant negative trace prevents the eigenvalues from ever both being zero. □

References

- Figueiredo, I.N.; Leal, C.; Romanazzi, G.; Engquist, B. Biomathematical model for simulating abnormal orifice patterns in colonic crypts. Math. Biosci. 2019, 315, 108221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins-Daarud, A.; Johnston, S.K.; Swanson, K.R. Quantifying uncertainty and robustness in a biomathematical model–based patient-specific response metric for glioblastoma. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2019, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibargüen-Mondragón, E.; Romero-Leiton, J.P.; Esteva, L.; Burbano-Rosero, E.M. Mathematical modeling of bacterial resistance to antibiotics by mutations and plasmids. J. Biol. Syst. 2016, 24, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclerc, Q.J.; Lindsay, J.A.; Knight, G.M. Mathematical modelling to study the horizontal transfer of antimicrobial resistance genes in bacteria: Current state of the field and recommendations. J. R. Soc. Interface 2019, 16, 20190260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudhagara, P.R.; Patel, A. Enhance the bacterial nitrate reductase production using mathematical and statistical model to formulate the affordable silver nanoparticle for the production of nanofinished fabric. Biomath Commun. Suppl. 2018, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Khattak, S.; Khan, M.N.; Riaz, M.B.; Lu, D.; Hussien, M.; Albalwi, M.D.; Jhangeer, A. Insights of temperature-dependent fluid characteristics on micropolar material in a rotating frame with cubic autocatalysis chemical reaction. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2024, 11, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmandouh, A. Dynamical Analysis of a Soliton Neuron Model: Bifurcations, Quasi-Periodic Behaviour, Chaotic Patterns, and Wave Solutions. Mathematics 2025, 13, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, T.S.; Elmandouh, A.; Attiya, A.A.; Khedr, A.Y. Bifurcation Analysis and Exact Wave Solutions for the Double-Chain Model of DNA. J. Math. 2022, 2022, 7188118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Riaz, M.B.; Dar, M.N.R.; Kanwal, R.; Sarwar, L.; Jhangeer, A. Computational study of effect of hybrid nanoparticles on hemodynamics and thermal transfer in ruptured arteries with pathological dilation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, A.; Mohan, B. Evolutionary dynamics of solitary wave profiles and abundant analytical solutions to a (3+1)-dimensional burgers system in ocean physics and hydrodynamics. J. Ocean. Eng. Sci. 2023, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, K.; Mayeli, P.; Kumar, D. New exact solutions of the coupled sine-Gordon equations in nonlinear optics using the modified Kudryashov method. J. Mod. Opt. 2018, 65, 361–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaber, A. Solitary and periodic wave solutions of (2+1)-dimensions of dispersive long wave equations on shallow waters. J. Ocean. Eng. Sci. 2021, 6, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Seadawy, A.R. Dispersive soliton solutions for shallow water wave system and modified Benjamin-Bona-Mahony equations via applications of mathematical methods. J. Ocean. Eng. Sci. 2021, 6, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, L.; Saha Ray, S.; Sahoo, S. New exact solutions of coupled Boussinesq–Burgers equations by Exp-function method. J. Ocean. Eng. Sci. 2017, 2, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Zhang, J.; Ye, C.; Pan, Z. New exact solutions of the (2+1)-dimensional KdV equation with variable coefficients. Phys. Lett. A 2005, 337, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmandouh, A.; Aljuaidan, A.; Elbrolosy, M. The integrability and modification to an auxiliary function method for solving the strain wave equation of a flexible rod with a finite deformation. Mathematics 2024, 12, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albalawi, S.M.; Elmandouh, A.A.; Sobhy, M. Integrability and dynamic behavior of a piezoelectro-magnetic circular rod. Mathematics 2024, 12, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbrolosy, M.; Elmandouh, A. Painlevé analysis, Lie symmetry and bifurcation for the dynamical model of radial dislocations in microtubules. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 13699–13714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Duan, C.; Yu, F. An improved Hirota bilinear method and new application for a nonlocal integrable complex modified Korteweg-de Vries (MKdV) equation. Phys. Lett. A 2019, 383, 1578–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yomba, E.; TC, K.; FB, P. On exact solutions of the generalized modified Ginzburg-Landau equation using Hirota S method. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1996, 65, 2337–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.Y. Auto-Bäcklund transformation with the solitons and similarity reductions for a generalized nonlinear shallow water wave equation. Qual. Theory Dyn. Syst. 2024, 23, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Li, L. Auto-Bäcklund transformation and exact solutions for a new integrable (2+1)-dimensional shallow water wave equation. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 115233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Feng, B. Geometric Theory of Ordinary Differential Equations and Bifurcation Problems; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Alharbi, M.; Elmandouh, A.; Elbrolosy, M. Study of Soliton Solutions, Bifurcation, Quasi-Periodic, and Chaotic Behaviour in the Fractional Coupled Schrödinger Equation. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshid, M.M.; Rahman, M.; Roshid, H.-O. Bifurcation, modulation instability analysis, observation of closed solutions and effect of dispersion coefficient on soliton in relativity and quantum mechanics. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 130, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Wang, L. Bifurcation Analysis and Exact Solutions of the (2+1)-Dimensional Mixed Fractional Broer-Kaup-Kupershmidt System Involving the Riemann-Liouville Fractional Derivative. Phys. Lett. A 2025, 560, 130947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, A.N.; Petrovsky, I.G.; Piskunov, N.S. Investigation of the Equation of Diffusion Combined with Increasing of the Substance and Its Application to a Biology Problem. Vestn. Mosk. Univ. Seriya I Mat. I Mekhanika 1937, 1, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, R.A. The wave of advance of advantageous genes. Ann. Eugen. 1937, 7, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, Z.; Taşcan, F. Application of the generalized Kudryashov method to the Kolmogorov-Petrovskii-Piskunov equation. Eskişeh. Tech. Univ. J. Sci. Technol. A Appl. Sci. Eng. 2024, 25, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayed, E.; Al-Nowehy, A.G. The Riccati equation method combined with the generalized extended (G′/G)-expansion method for solving the nonlinear KPP equation. J. Math. Res. Appl. 2017, 37, 577–590. [Google Scholar]

- Durur, H. The modified sub equation method to Kolmogorov-Petrovskii-Piskunov equation. Celal Bayar Univ. J. Sci. 2025, 21, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Li, W.; Wan, Q. Using G′/G-expansion method to seek the traveling wave solution of Kolmogorov–Petrovskii–Piskunov equation. Appl. Math. Comput. 2011, 217, 5860–5865. [Google Scholar]

- Roshid, M.M.; Rahman, M.; Or-Roshid, H. Effect of the nonlinear dispersive coefficient on time-dependent variable coefficient soliton solutions of the Kolmogorov-Petrovsky-Piskunov model arising in biological and chemical science. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezrodnykh, S.; Pikulin, S. Numerical-Analytical Method for Nonlinear Equations of Kolmogorov–Petrovskii–Piskunov Type. Comput. Math. Math. Phys. 2024, 64, 2484–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khater, M.M.A.; Mohamed, M.S.; Attia, R.A.M. On semi analytical and numerical simulations for a mathematical biological model; the time-fractional nonlinear Kolmogorov–Petrovskii–Piskunov (KPP) equation. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 144, 110676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.G.; Hu, X.K.; Ling, X.Q.; Li, W.X. Approximate analytical solution of the generalized Kolmogorov-Petrovsky-Piskunov equation with cubic nonlinearity. Acta Math. Appl. Sin. Engl. Ser. 2023, 39, 424–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gepreel, K.A. The homotopy perturbation method applied to the nonlinear fractional Kolmogorov–Petrovskii–Piskunov equations. Appl. Math. Lett. 2011, 24, 1428–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Shah, K.; Abdeljawad, T. Study of traveling soliton and fronts phenomena in fractional Kolmogorov-Petrovskii-Piskunov equation. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 055259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Guo, Y. New exact solutions to the Fitzhugh–Nagumo equation. Appl. Math. Comput. 2006, 180, 524–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, M.; Momoniat, E.; Mahomed, F. Approximate conditional symmetries and approximate solutions of the perturbed Fitzhugh–Nagumo equation. J. Math. Phys. 2005, 46, 1839276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazwaz, A.M. Analytic study on Burgers, Fisher, Huxley equations and combined forms of these equations. Appl. Math. Comput. 2008, 195, 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.; Villaverde, A.F.; Banga, J.R.; Vázquez, S.; Morán, F. A generalized Fisher equation and its utility in chemical kinetics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 12777–12781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecarpentier, Y.; Blanc, F.X.; Quillard, J.; Hébert, J.L.; Krokidis, X.; Coirault, C. Statistical mechanics of myosin molecular motors in skeletal muscles. J. Theor. Biol. 2005, 235, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabor, M. Chaos and Integrability in Nonlinear Dynamics: An Introduction; Wiley-Interscience: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Nemytskii, V.V. Qualitative Theory of Differential Equations; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, R.; Chauhan, A. Lie Symmetry Analysis and Some Exact Solutions of (2+1)-Dimensional KdV-Burgers Equation. Int. J. Appl. Comput. Math. 2019, 15, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehia, H. Rigid Body Dynamics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ablowitz, M.J.; Ramani, A.; Segur, H. A connection between nonlinear evolution equations and ordinary differential equations of P-type. II. J. Math. Phys. 1980, 21, 1006–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, Y.A. Elements of Applied Bifurcation Theory; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).