1. Introduction

The numerical solution of stochastic differential equations (SDEs) has been an active research area for decades, driven by their wide applications in physics, finance, and biology [

1]. Since explicitly solvable SDEs are rare in practical applications, constructing numerical methods for SDEs has always been an active area of research [

2]. Beyond achieving basic convergence, a paramount goal in this field is the development of structure-preserving numerical methods, also known as geometric numerical integrators (GNI). These methods are designed to replicate fundamental geometric properties of the exact solution, such as symplecticity [

3,

4,

5,

6], conserved quantities [

7,

8,

9] or Lie group structure [

10,

11], leading to more stable and physically realistic long-term simulations.

The preservation of conserved quantities is particularly crucial, as these conserved quantities determine the manifold on which the exact solution evolves. For SDEs with a single conserved quantity, such as stochastic Hamiltonian systems, considerable progress has been made. Methods like the stochastic discrete gradient [

12] and linear projection [

13] techniques have proven successful in preserving a single invariant like energy.

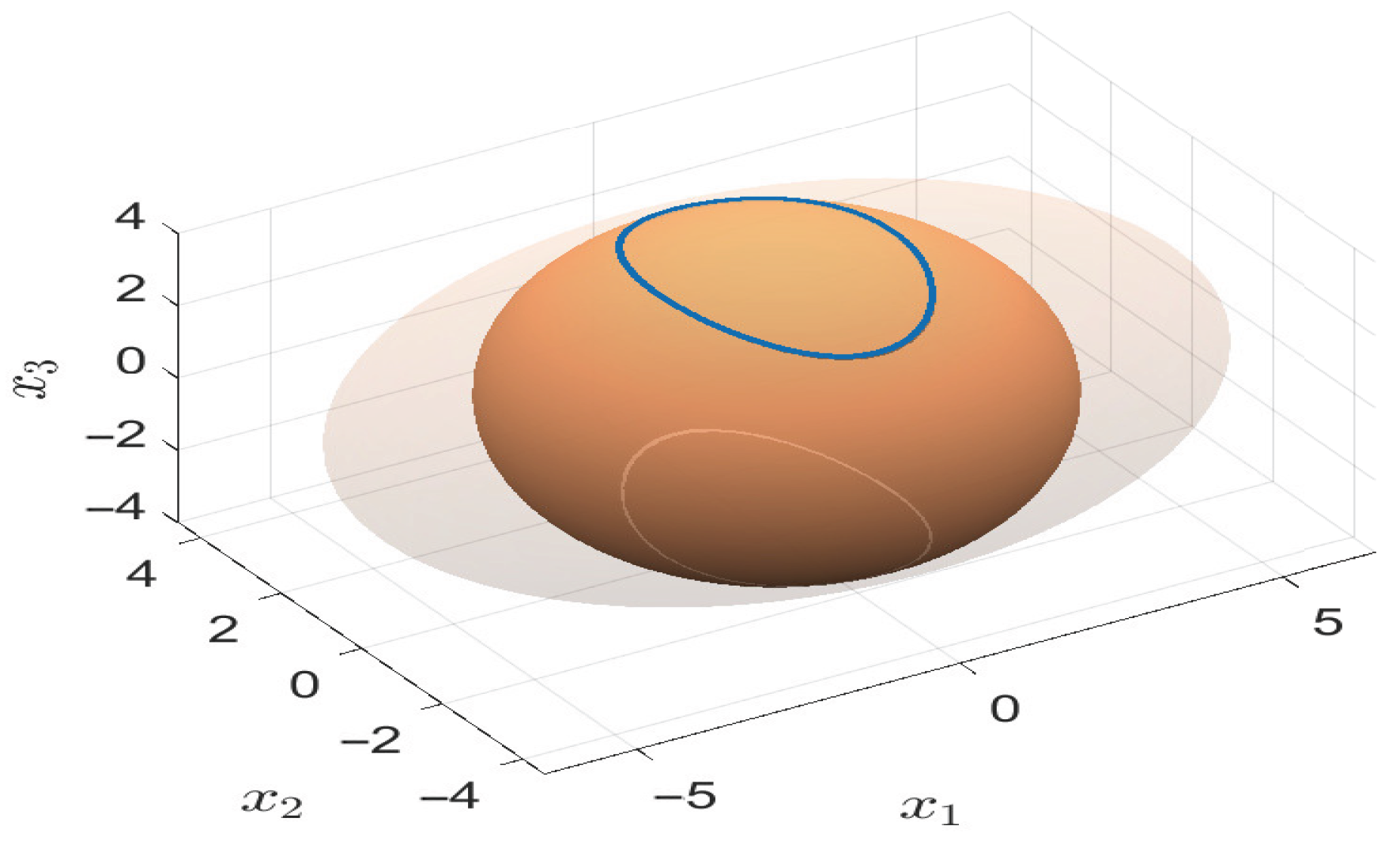

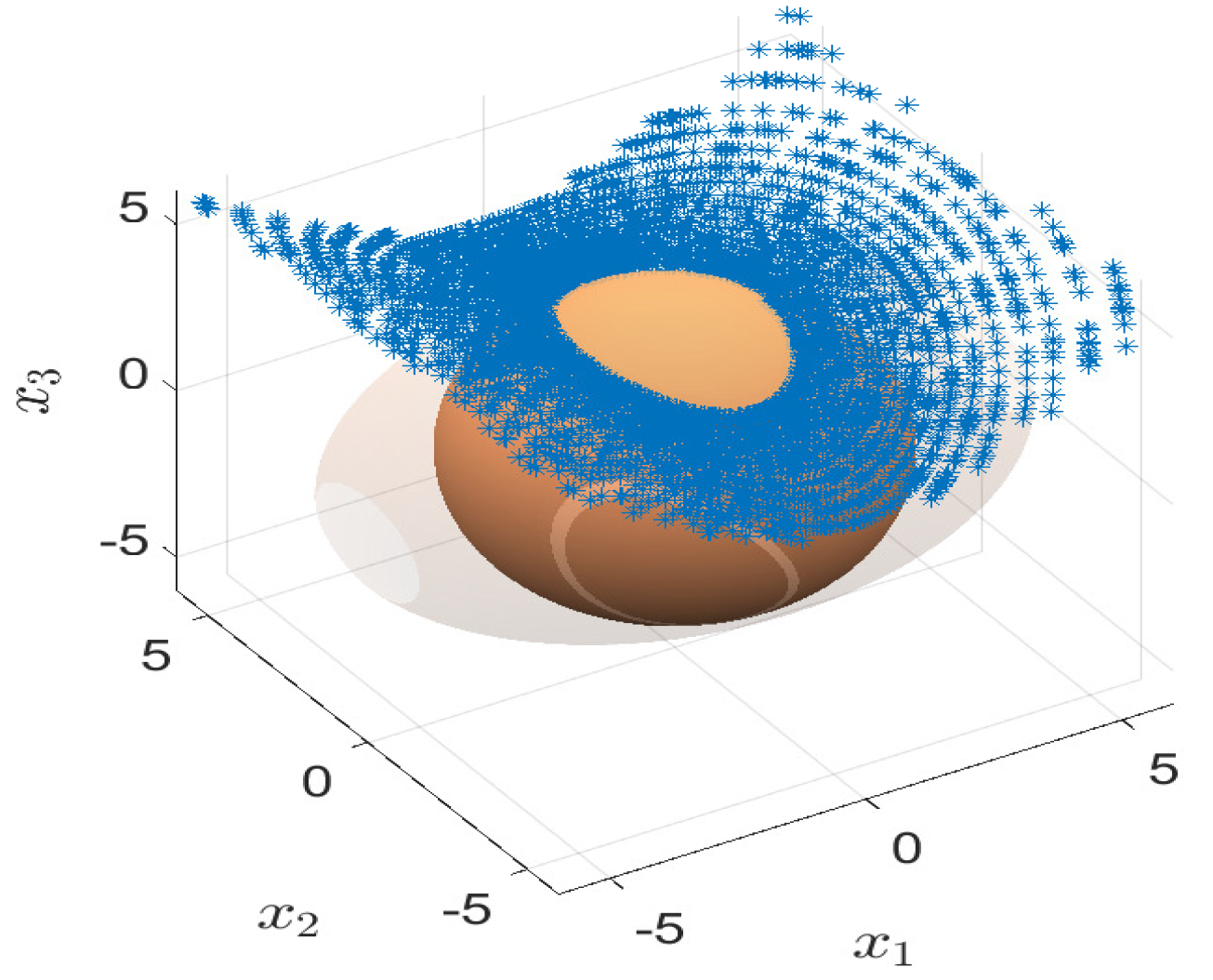

However, many physically important systems are governed by multiple conserved quantities simultaneously. Classical examples include the stochastic rigid body dynamics (preserving angular momentum and energy) and the stochastic pendulum problem (preserving constraint and energy). In such cases, the exact solution evolves on the intersection of manifolds defined by these invariants,

Traditional numerical methods, even those preserving one conserved quantity, often fail to capture this complex geometry, leading to solutions that drift away from the true manifold and produce incorrect dynamical behavior. This underscores the necessity for numerical schemes that can preserve all conserved quantities.

Despite its importance, the literature on numerical methods for SDEs with multiple conserved quantities is relatively sparse. A direct application of the stochastic linear projection method [

13] to multiple invariants is possible but introduces several Lagrange multipliers, significantly increasing computational complexity. The stochastic Average Vector Field (AVF) method has been adapted for this purpose [

14]. Integrators that exactly conserve all the first integrals simultaneously are defined by the orthogonal complement of an arbitrary set of discrete gradients [

15]. Numerical schemes for stochastic Poisson systems with multiple invariant Hamiltonians are proposed in [

7], which simultaneously retain all the invariant Hamiltonian properties of the stochastic Poisson system. Current research efforts remain to be further enriched.

Motivated by this fact, we address this challenge by developing and analyzing two distinct projection-based frameworks for constructing multiple conserved quantity preserving methods. The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

We define a discrete tangent space using discrete gradients and project the increments of any underlying numerical method onto it, constructing the discrete tangent space projection method, which ensures the numerical solution remains on the correct discrete manifold.

We reformulate the stochastic differential equation on the manifold using local coordinates (e.g., tangent space parametrization), numerically solve the transformed equation, and map the results back to the original space, constructing a local coordinates-based method, which inherently preserves the conserved quantities.

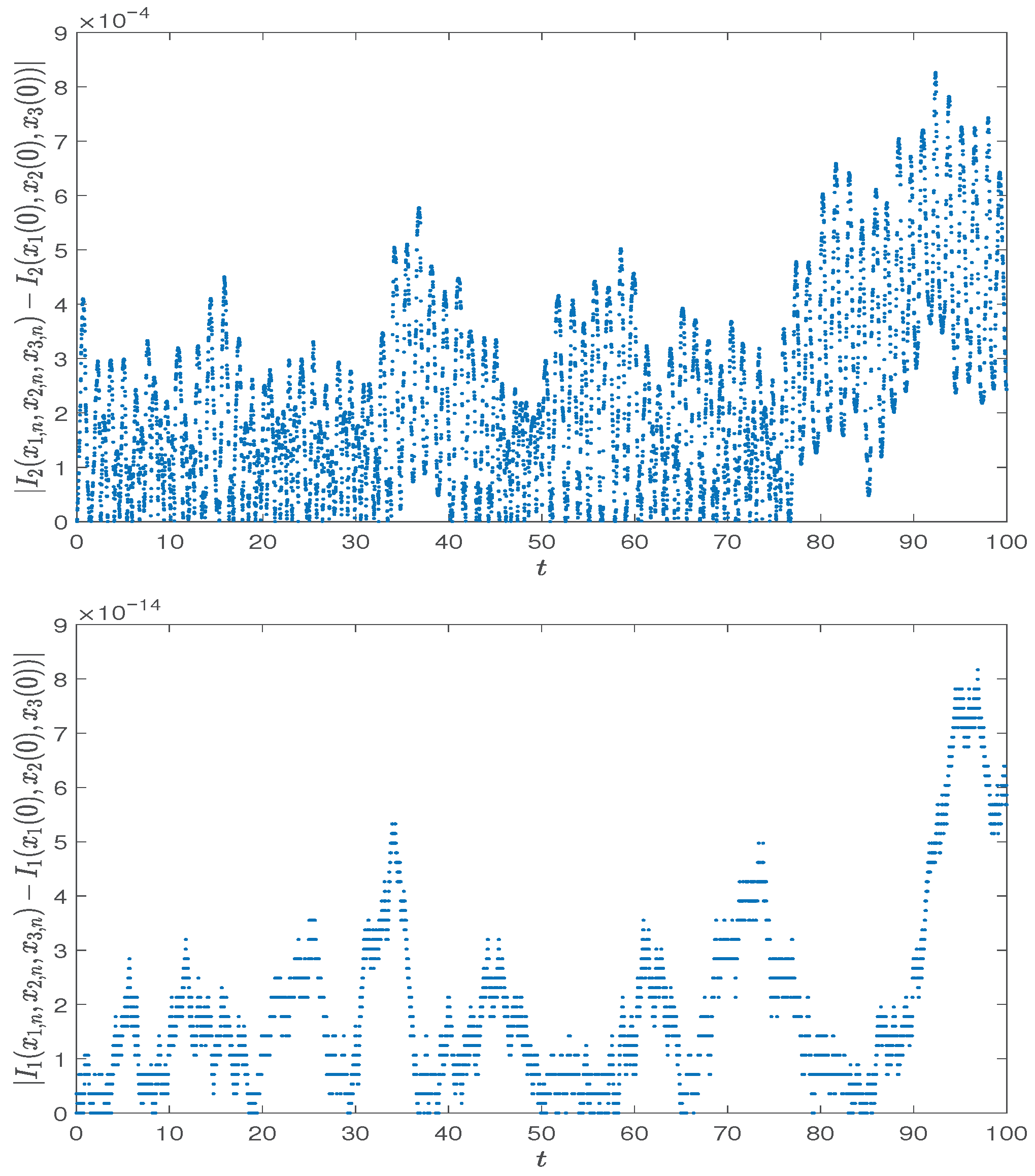

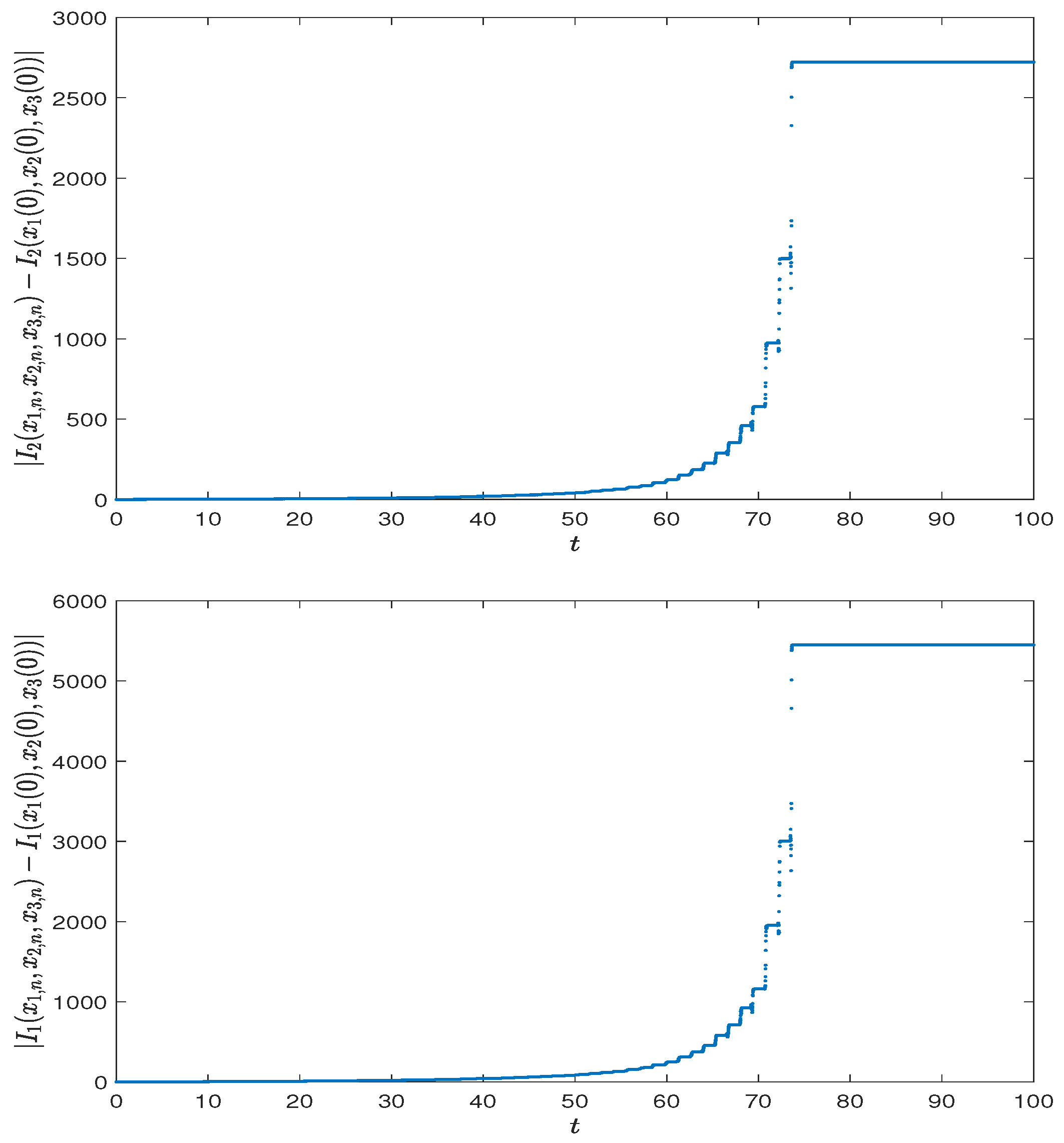

We rigorously prove that both methods retain the mean-square convergence order of the underlying numerical schemes. Additionally, we introduce a simplified strategy that combines the multiple invariants into one, enabling the use of efficient single-invariant-preserving methods at a slightly reduced conservation accuracy, thus offering a valuable tool for practical applications where computational cost is a concern.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the stochastic projection method based on the discrete gradients and proves that the proposed stochastic projection method has the same mean-square convergence order as their underlying methods.

Section 3 develops a kind of conserved-quantity-preserving numerical method based on local coordinates. SDEs in the space of given local coordinates are solved numerically, then the numerical solutions are projected back to the manifold

via the local coordinate map to obtain the numerical solutions to the original SDEs.

Section 4 introduces a simplified strategy for applying the stochastic linear projection method to SDEs with multiple conserved quantities; it reduces the computational expenses at the cost of losing some accuracy of preserving the conserved quantities. Finally, in

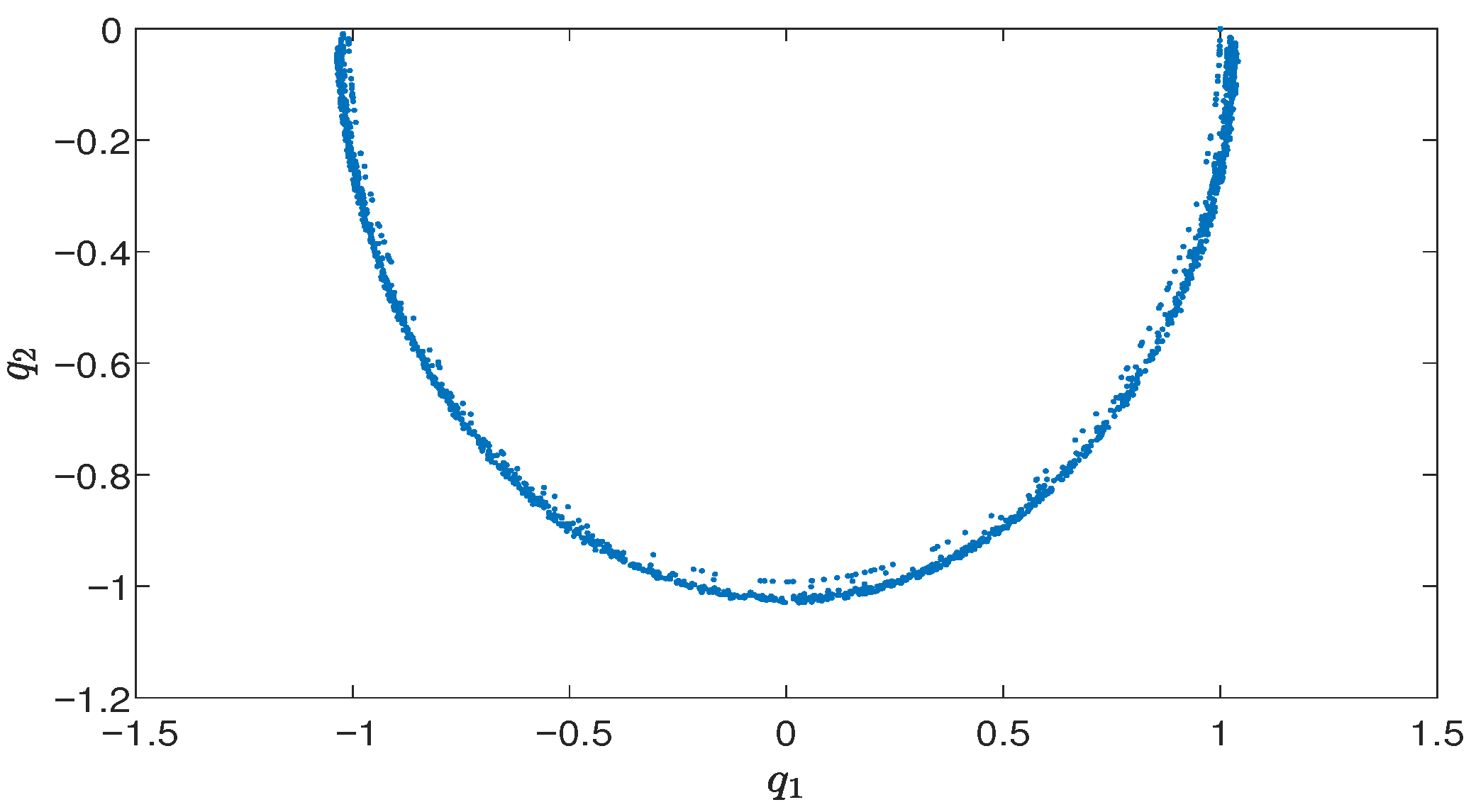

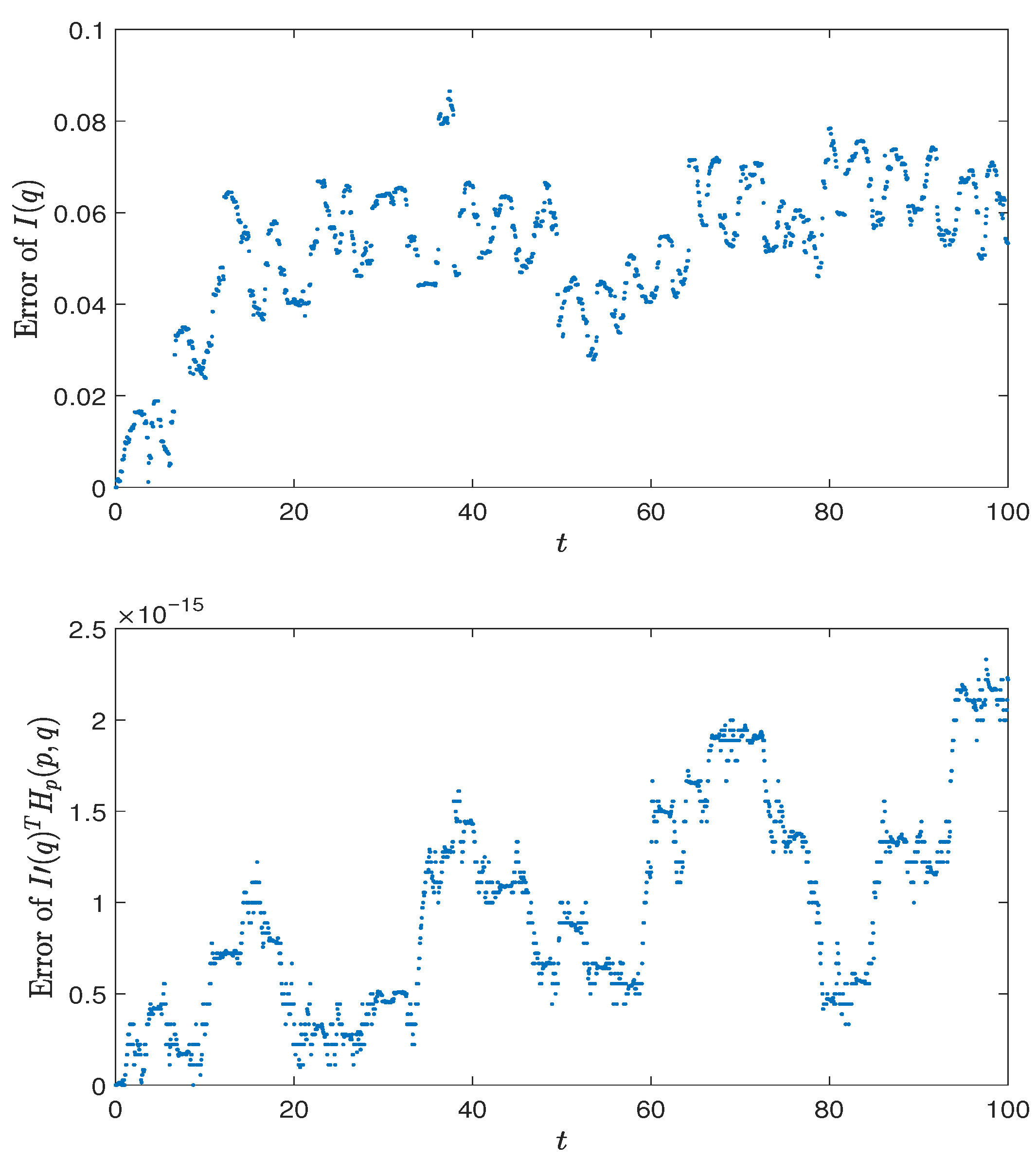

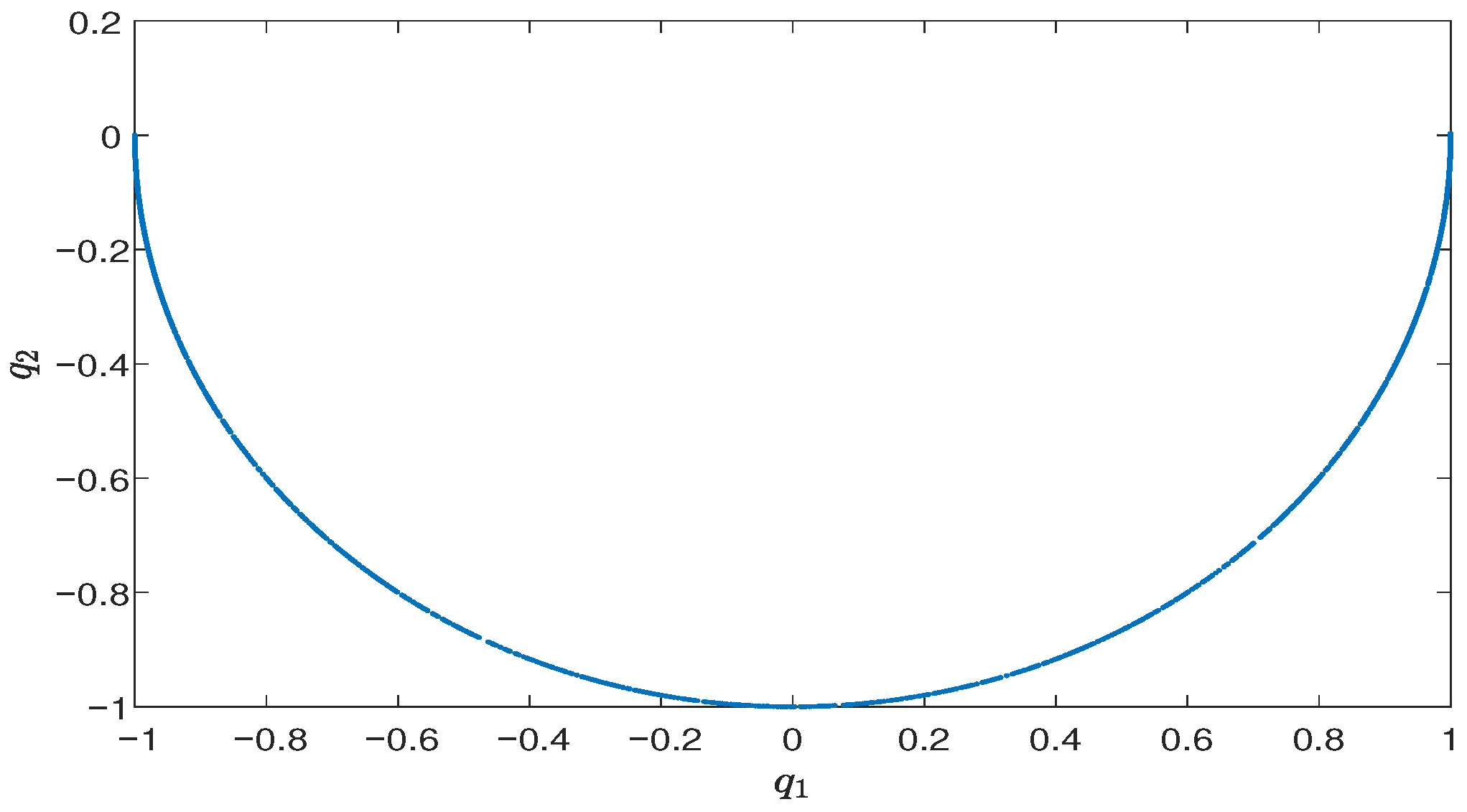

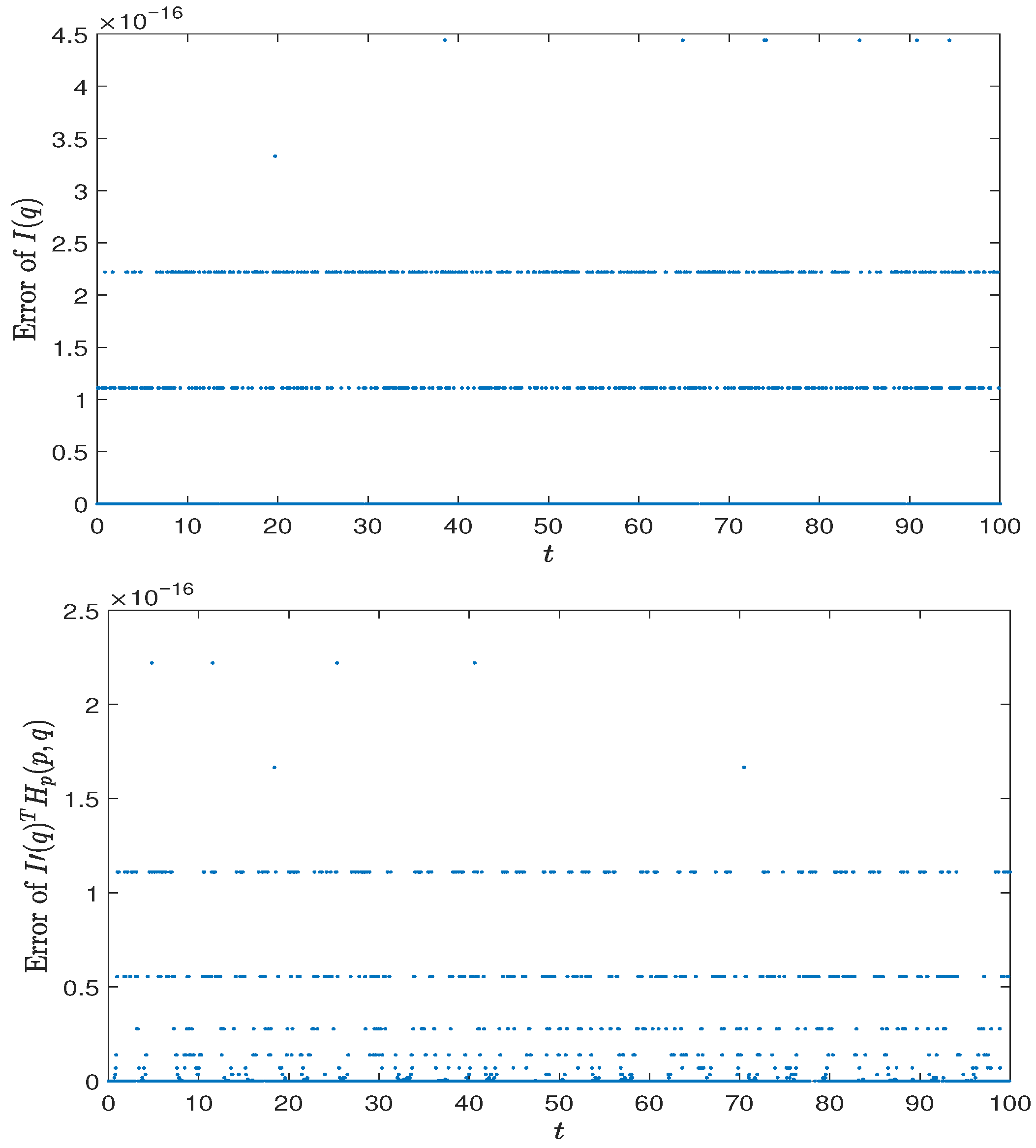

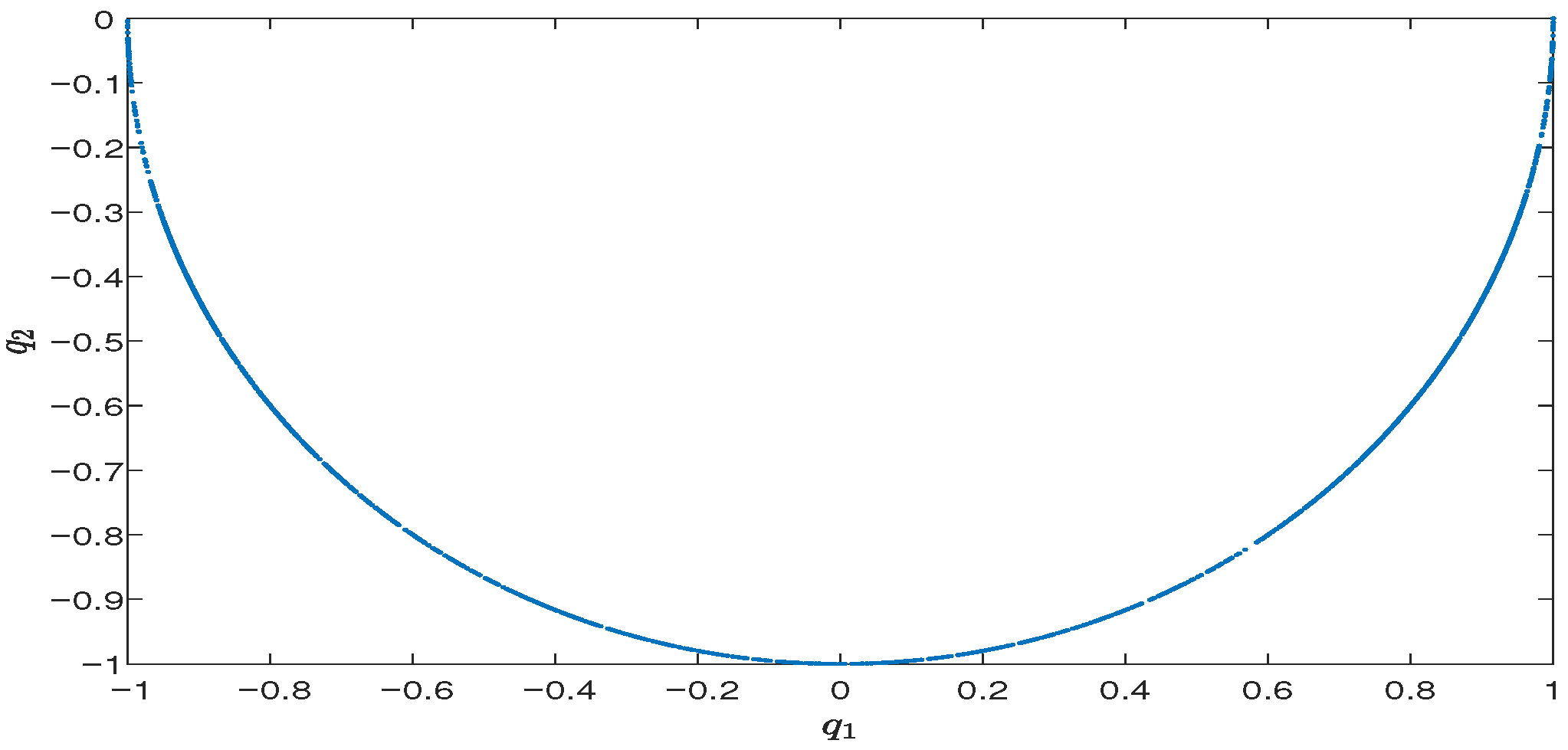

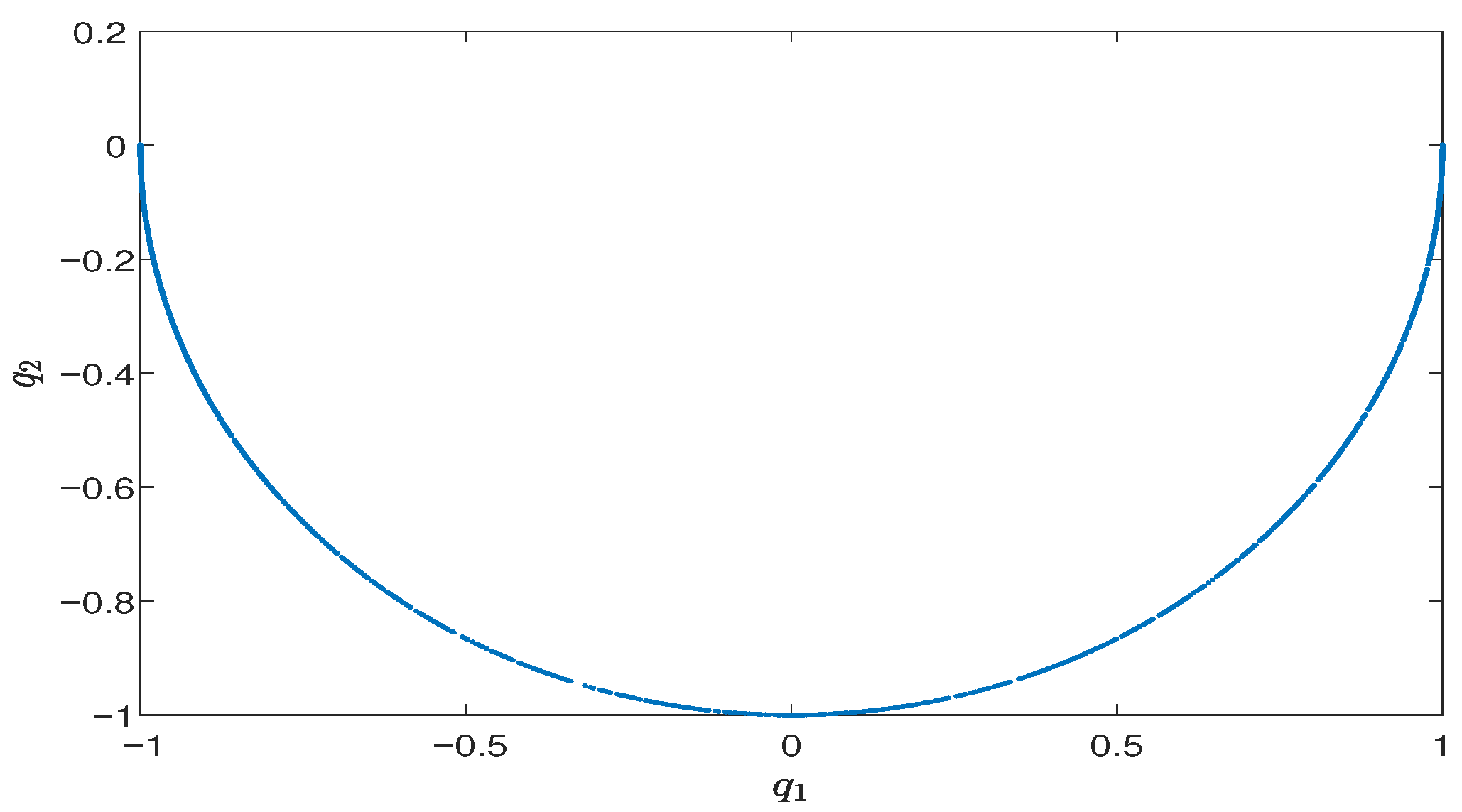

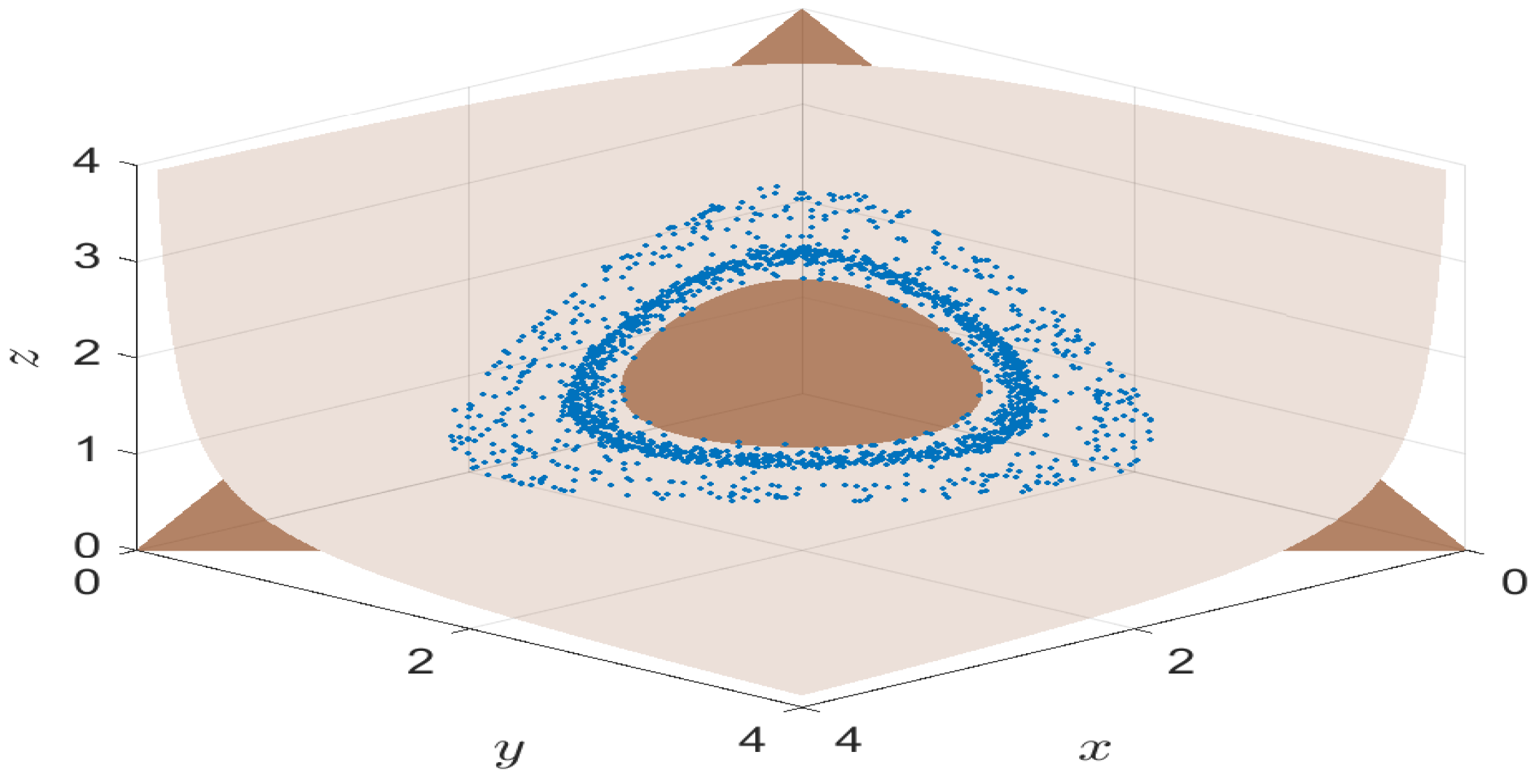

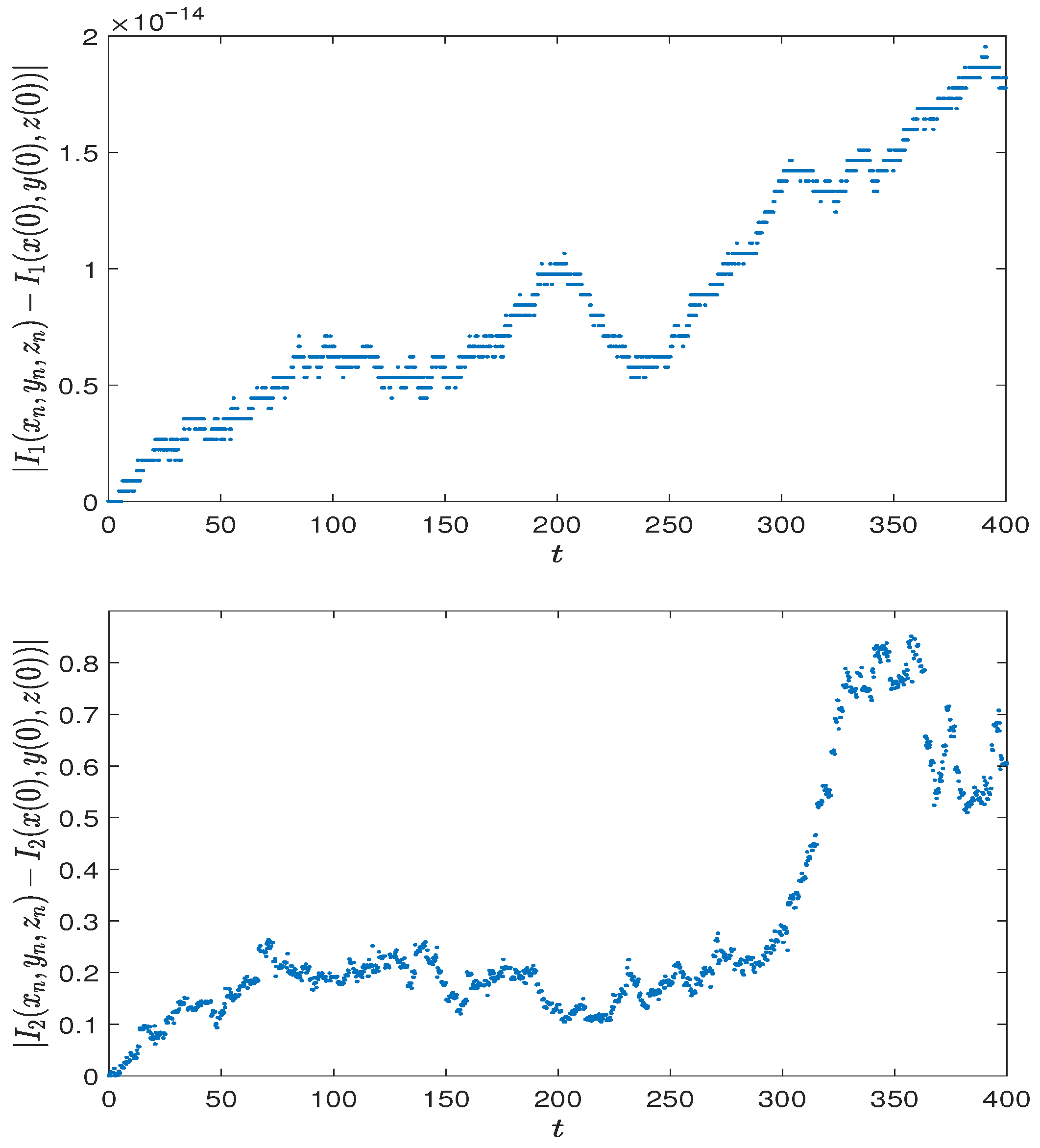

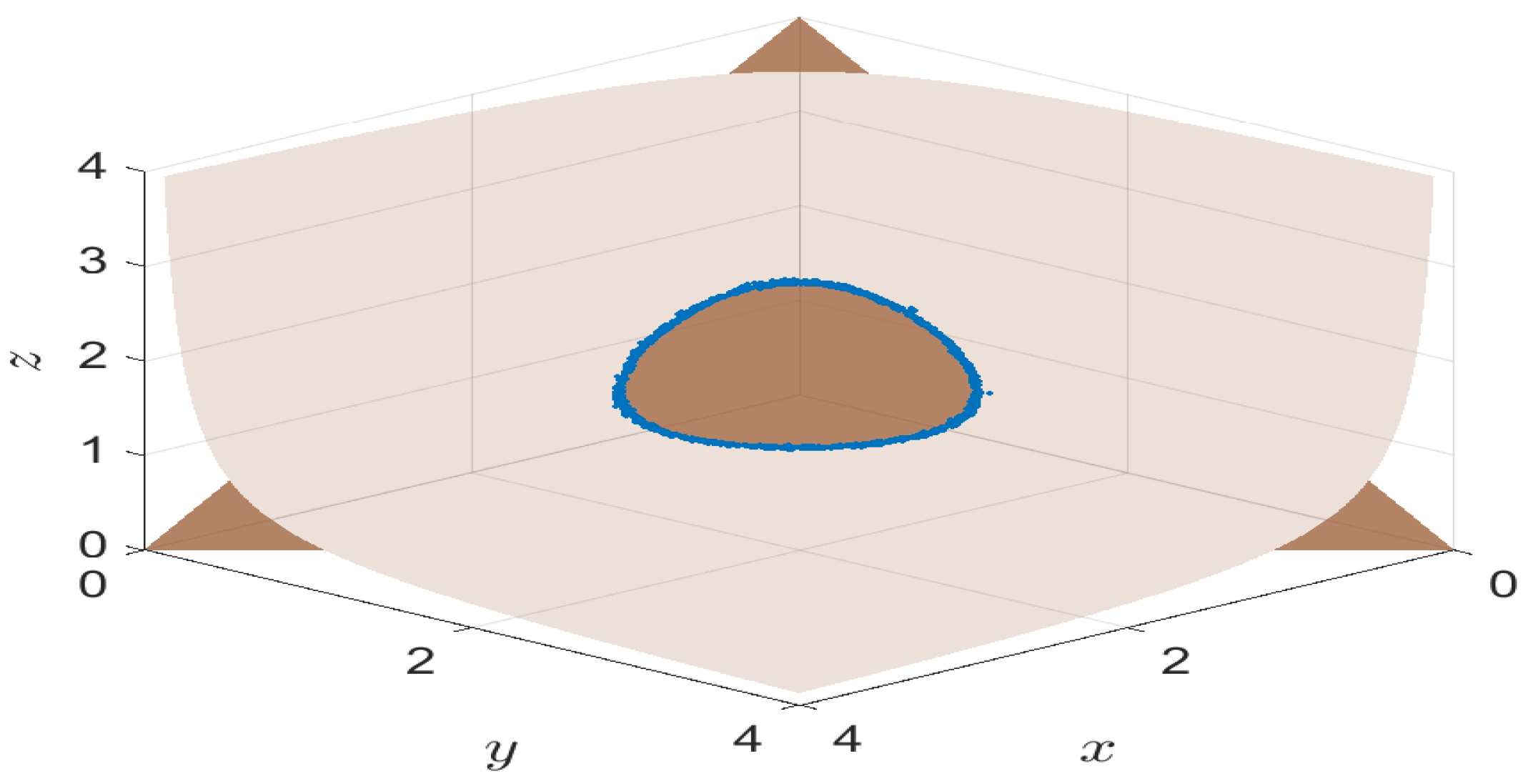

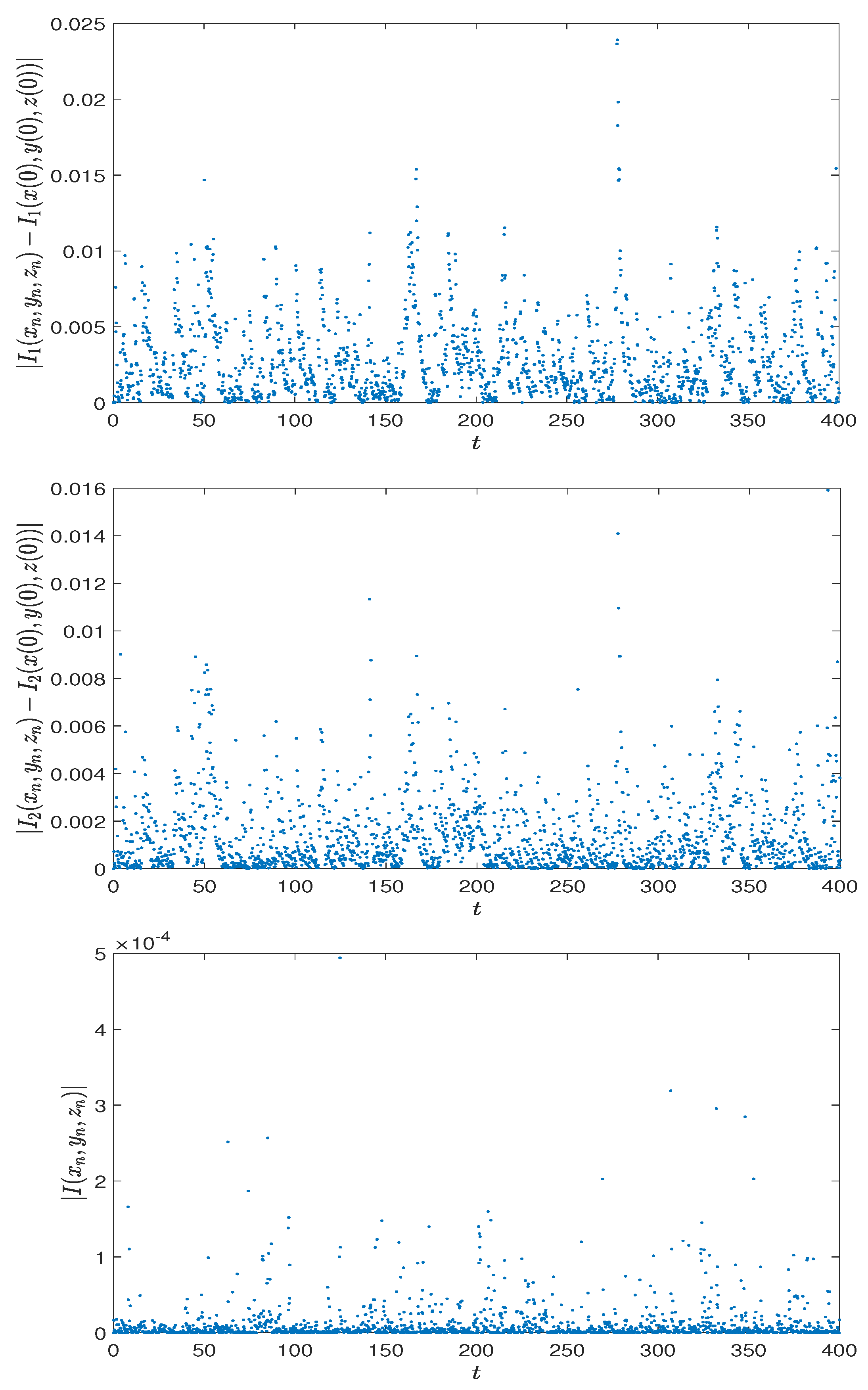

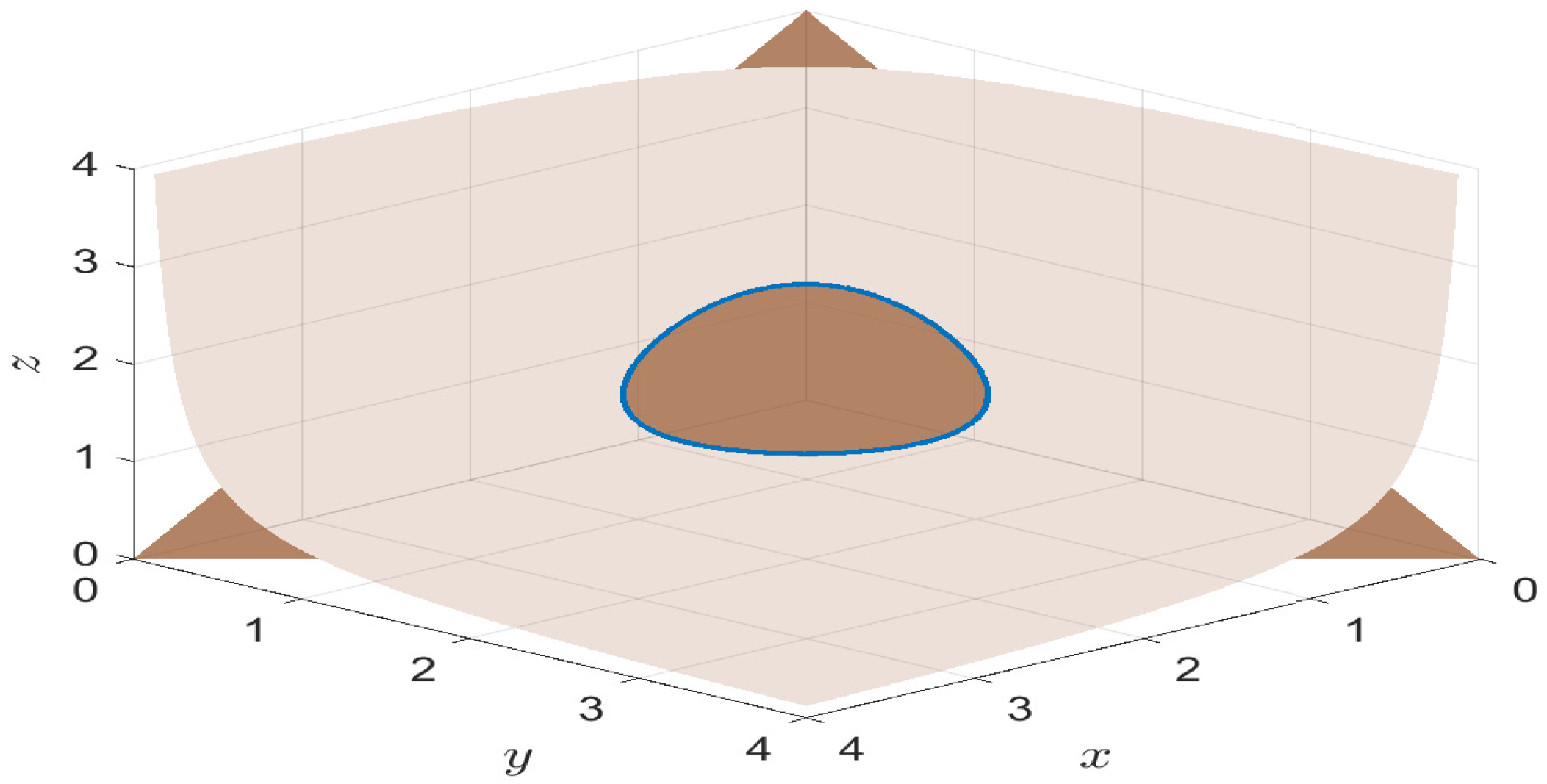

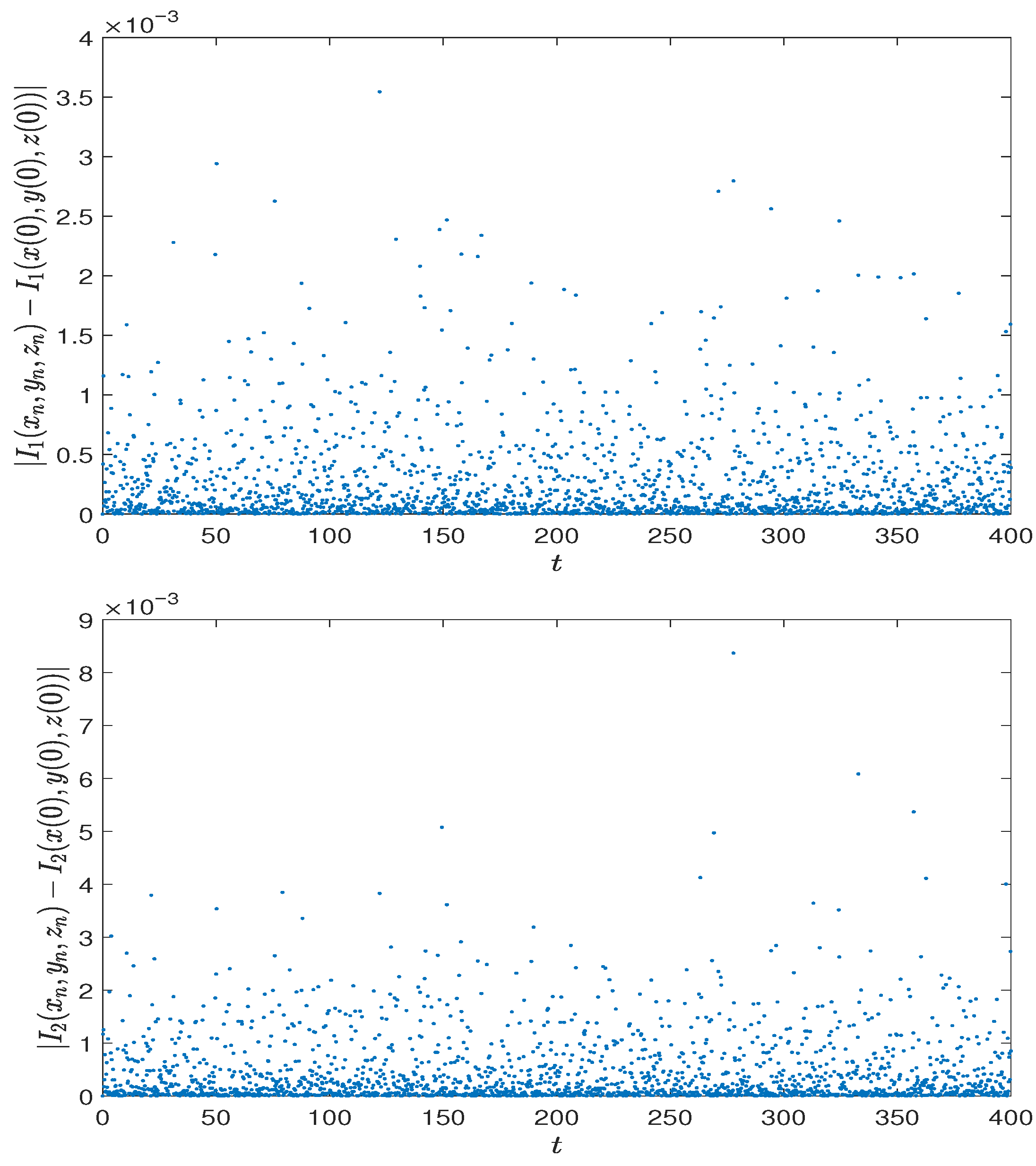

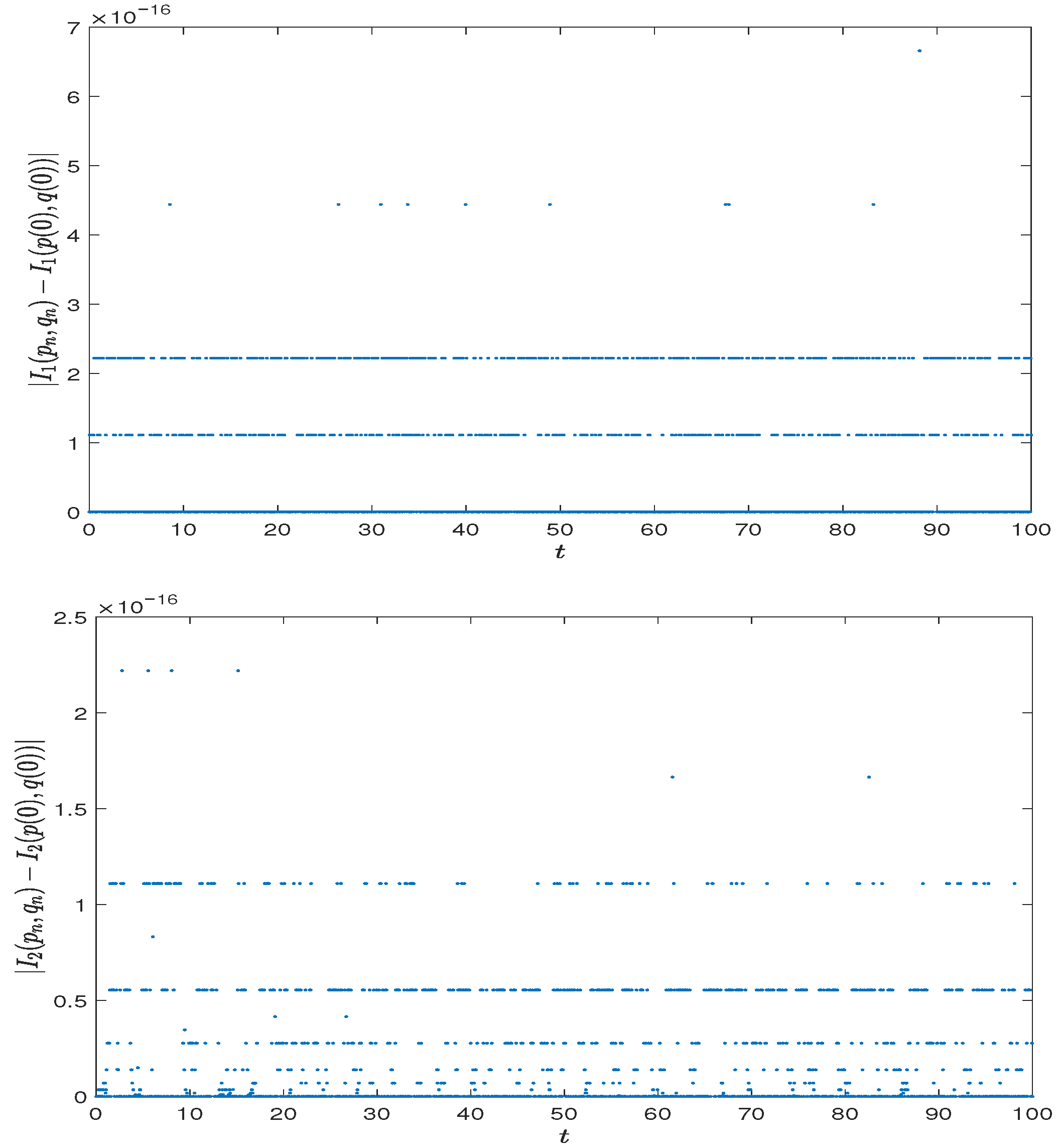

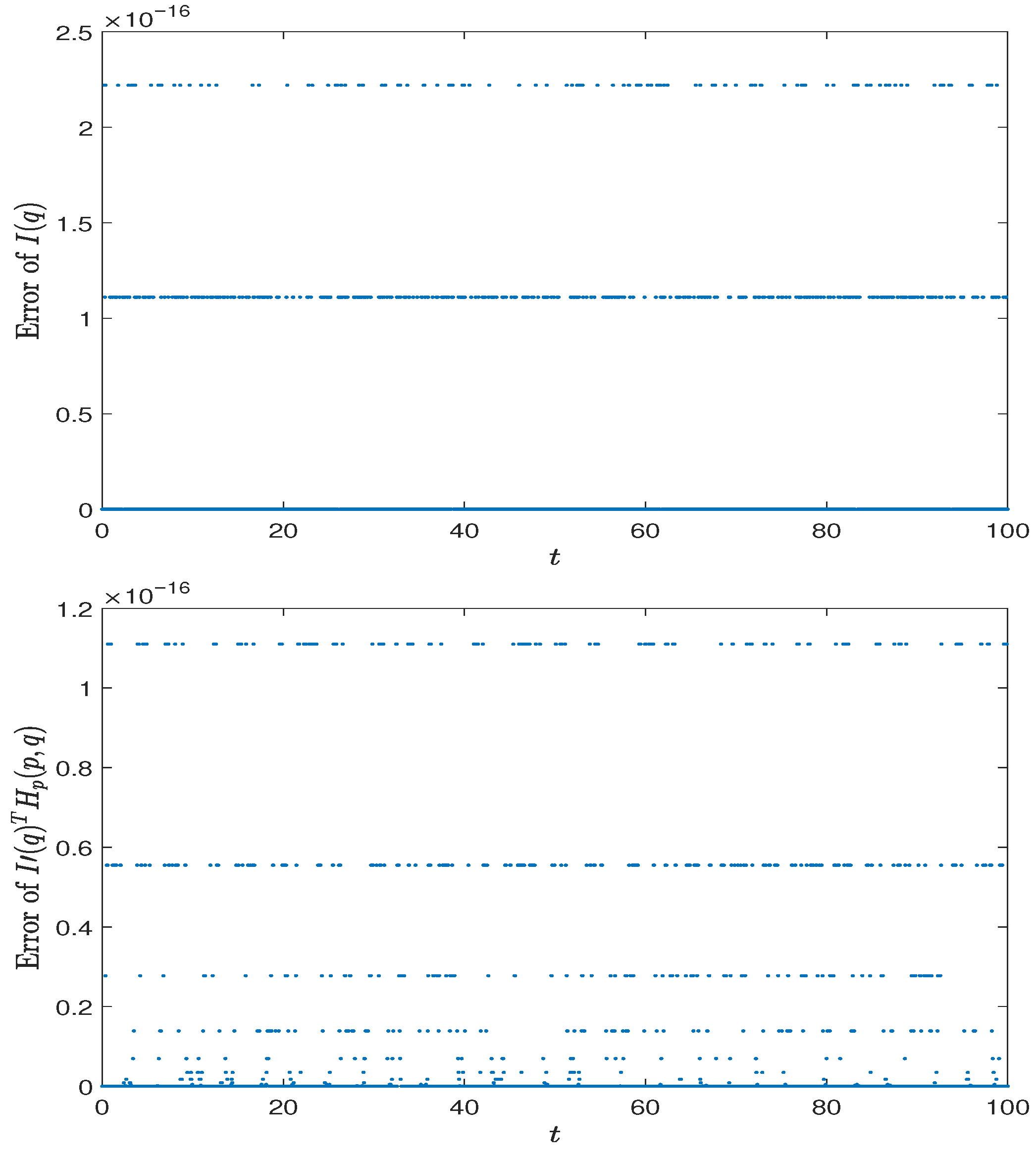

Section 5, numerical examples are presented to support the theoretical results.

In the sequel, we will use the following basic notations:

,

denotes the exact solution to SDE (

3) with initial value

, which is a

-valued random variable satisfying

,

is the Euclidean norm. For convenience, we usually use

to denote the exact solution

of (

3) at

.

Time interval is partitioned into N equal parts using division points , so that , with .

The one-step approximation of a numerical method from point

x at time

t is denoted as

2. Stochastic Projection Method Based on Discrete Gradient

In this section, we present the stochastic projection method based on the discrete gradients of the conserved quantities for the following SDEs in the Stratonovich sense,

where

,

are independent one-dimensional standard Wiener processes defined on a complete filtered probability space

fulfilling the usual conditions, and functions

f,

,

satisfy the conditions under which Equation (

3) has a unique solution [

1].

Definition 1 ([

12])

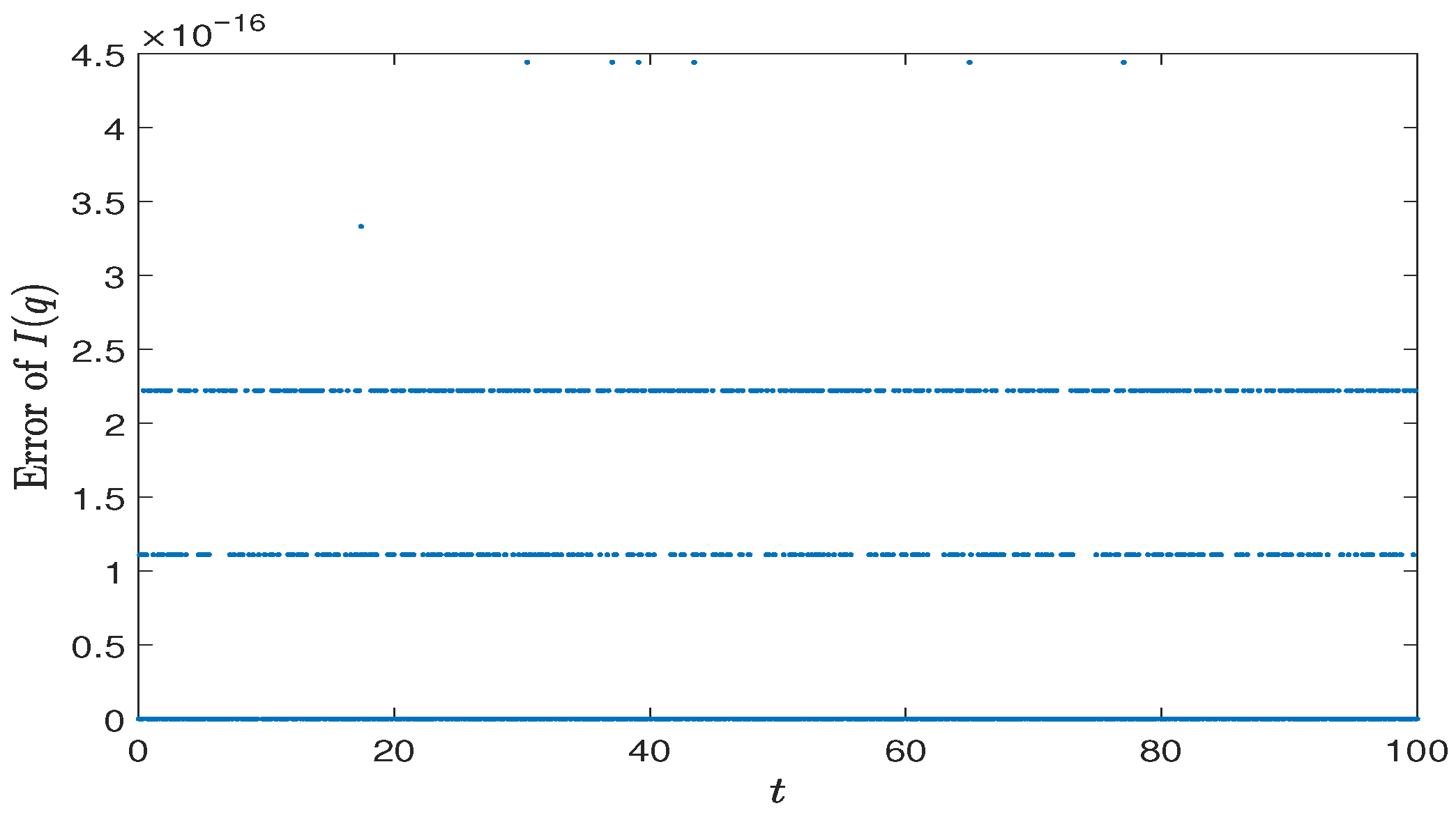

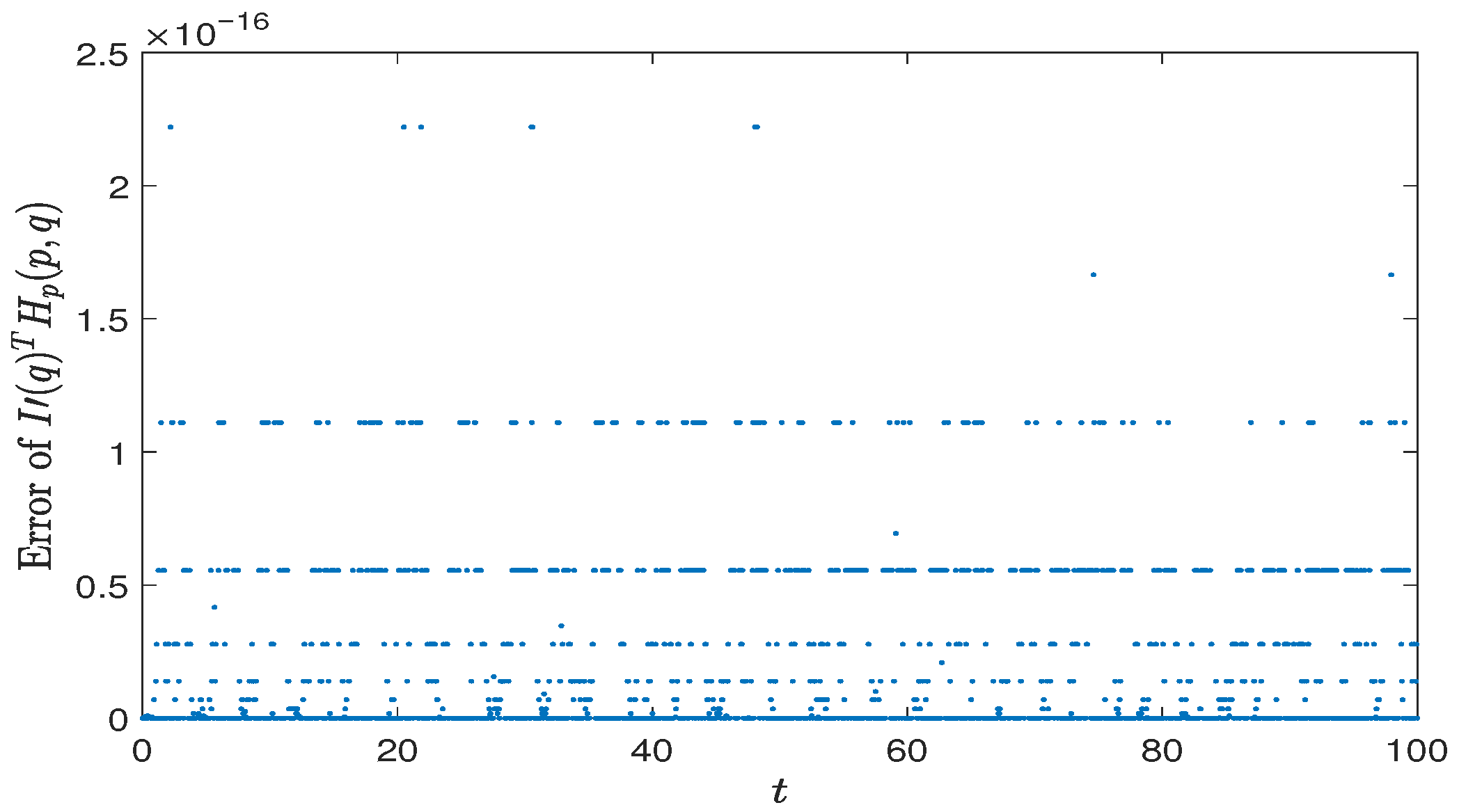

. A differentiable function I is called a conserved quantity of SDE (3) ifhold for all . Definition 2. For a differentiable function I, a continuous function , x, , is called a discrete gradient of I if Moreover, if , it is called symmetric discrete gradient.

Notice that the tangent space

of

at point

x is the orthogonal complement to the subspace spanned by

, …,

, i.e.,

Based on this fact, we define the discrete tangent space by using the discrete gradient operator .

Definition 3. For a given discrete gradient operator , letwhere u, is called the discrete tangent space of at , vector is called discrete tangent vector. Specially, . The numerical method constructed by the one-step approximation of Equation (

2) can be written as

Obviously, Equation (

8) preserves the conserved quantities of Equation (

3) if and only if

holds for

,

. By Definition 1, we have

which means

. Thus, we obtain the following theorem:

Theorem 1. The numerical method in Equation (8) preserves all conserved quantities of Equation (3) if and only if Now, we propose the stochastic projection method in the following form:

where

is a smooth projection operator to be determined which project

to the discrete gradient tangent space

of

at

.

In order to obtain the formula of the projection operator

, we first compute the reduced QR decomposition

where

has orthonormal columns and

is an upper triangular matrix with

. Then the projection operator can be defined as

where

is the identity operator.

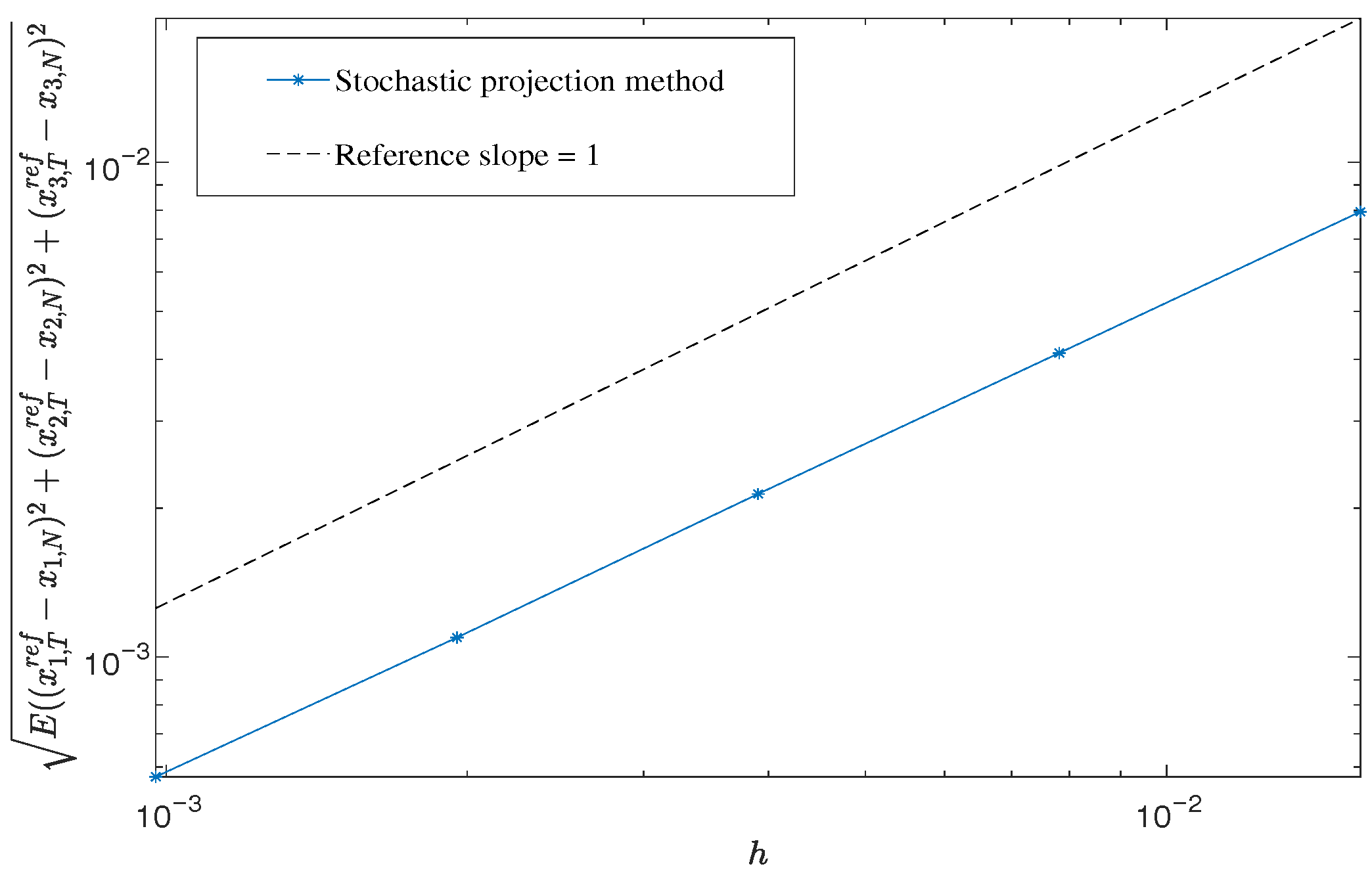

Remark 1. Compared with the standard stochastic linear projection method [13], it is easier to construct symmetric numerical methods in the form of Equation (10), since if the discrete gradient and the underlying method are symmetric, then the stochastic projection method in Equation (10) is symmetric [16]. Next we illustrate the mean-square convergence of the stochastic projection method in Equation (

10) by using the following lemma proposed in [

2].

Lemma 1 ([

2])

. Suppose that the one-step approximation satisfieswith , then for any ,holds, i.e., the numerical method constructed using the one-step approximation is of mean-square convergence order p. Theorem 2. Under the assumption that the projection operator has bounded second moment and has uniformly bounded partial derivatives, then the stochastic projection method in Equation (10) has mean-square convergence order p, if the underlying numerical method in Equation (8) has mean-square convergence order p. Proof. For the one-step approximation of the stochastic projection method

by the Taylor expansion, we have

According to the assumption that

has uniformly bounded partial derivatives, by triangle inequality and mean value inequality, we have the following estimations:

for some constant

C. We need to point out that, in order to simplify the notations, we employ a generic positive constant

C throughout this paper, which is independent of

but may vary with different formulas.

Notice that the image of

is the orthogonal complement to

, which means it belongs to the subspace

However, by the definition of the discrete gradient operator, we have

, which means

Thus, the second term in above equality is equal to zero. So, by assumption, we have

The proof is completed according to Theorem 1. □

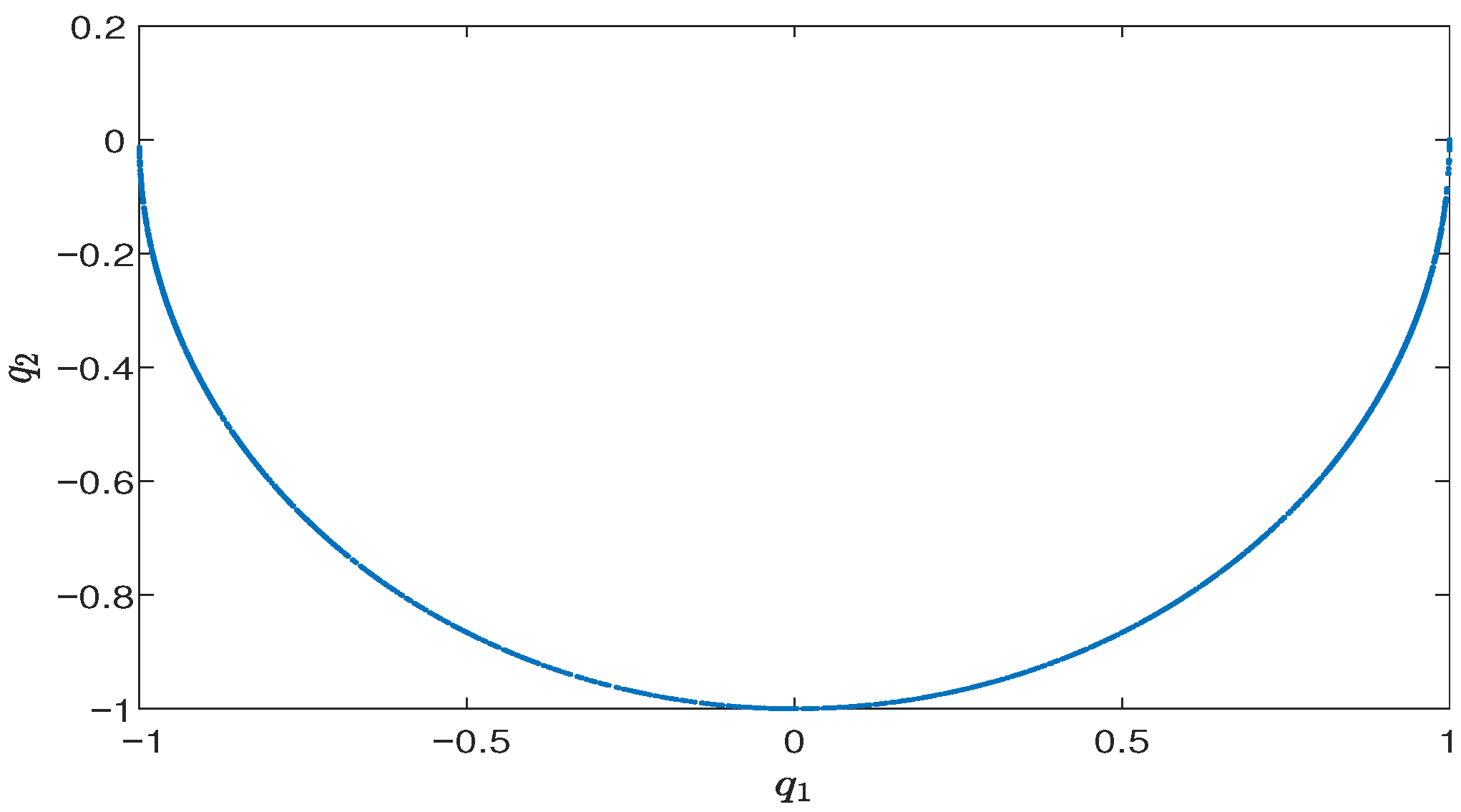

3. Conserved-Quantity-Preserving Method Based on Local Coordinates

For the convenience of the following discussion, in this section, we shift the value of the conserved quantities to zero and define

,

. Then, we use local coordinates to characterize the manifold

Let

be a neighborhood of 0, and

is a differentiable function satisfying

and

has full rank

. Then, for sufficiently small

V, the manifold

can be locally defined by

Here, variables

z are called parameters or local coordinates [

17]. Based on the local coordinates near

, we try to rewrite the solution to Equation (

3) as

. If it is true, then, by differentiating, we must have

thus

where

denotes the pseudo-inverse of

. Now, the original problem in Equation (

3) on manifold

is transformed to the problem in Equation (

16) in the local coordinates. Based on this idea, we can construct numerical methods for Equation (

3) by the following Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Numerical method based on local coordinates |

|

Generally, there are many choices of the local coordinates (e.g., generalized coordinate partitioning, tangent space parametrization, etc.; see [

17]). In this section, we choose the tangent space parametrization. The tangent space parametrization of

near

is

where the columns of

are the orthonormal basis of

, and

,

,

is determined by

. Differentiating Equation (

17) and inserting the result into Equation (

15), we have

Since

and

, we get the SDEs in the local coordinates

We obtain numerical solutions to Equation (

3) by transforming the numerical solutions to Equation (

18) in the space of local coordinates obtained by some underlying method back to the manifold via the local coordinate map

.

Remark 2. The columns of , which are the orthonormal basis of , can be obtained by computing the QR decomposition of ,the columns of are given by the first columns of . The following theorem shows that the numerical method based on the tangent space parametrization can preserve multiple conserved quantities and has the same mean-square convergence order as the underlying method:

Theorem 3. Suppose the underlying numerical method in Algorithm 1 has mean-square convergence order p, and has uniformly bounded derivatives, has full rank and ; then the numerical method constructed by Algorithm 1 preserves all conserved quantities of Equation (3) and also has mean-square convergence order p. Proof. The formula of the numerical method constructed by Algorithm 1 reads

where

collects the orthonormal basis of

and

u is determined by

. Consider the function

, we have

and

, then by the implicit function theorem, there locally exists a

u such that

, which means the numerical solution

preserves all conserved quantities of Equation (

3).

For the mean-square convergence order of numerical method in Equation (

19), by the mean value theorem, we have

where

. By the property of the local coordinates and the assumption that the underlying numerical method has mean-square convergence order

p, we have

which completes the proof. □

Remark 3. As we know, the choice of the local coordinates is not unique. If we replace in Equation (17) by discrete gradient , and replace by whose columns are the orthonormal basis of the left null-space of , we obtain the discrete tangent space parametrization. Then we can analyze the numerical method based on the discrete tangent space parametrization in the similar way as above. In addition, since the formula of the discrete gradient is not unique, one may have freedom to design numerical methods with other properties such as symmetry. 4. Simplified Strategy for Nearly Preserving the Multiple Conserved Quantities

Generally, preserving only some of the conserved quantities cannot ensure that the numerical solution correctly describes the dynamic behavior of the original SDEs. However, when the conserved-quantity-preserving methods for SDEs with a single conserved quantity, such as the standard stochastic linear projection method [

13], are directly applied to the SDEs with multiple conserved quantities, the computational costs may increase significantly. These two aspects conflict with each other in practical applications. So, in order to decrease the computational costs in practical applications while keeping the dynamic behavior of numerical solutions correct, we relax the constraints

to obtain the nearly conserved-quantity-preserving method. Let

it is easy to verify that if

are conserved quantities of the original SDE (

3), then Equation (

22) is also conserved along the exact solution to Equation (

3). Conversely,

is a particular solution to equation

. So, we take the SDE (

3) with a single conserved quantity

instead of the original SDE with

M conserved quantities into consideration, and apply conserved-quantity-preserving methods for SDEs with a single conserved quantity, such as the standard stochastic linear projection method, to this problem. The conserved quantities of the original SDE

are preserved in the sense that

.