Abstract

To address the problem of the proton exchange membrane fuel cell (PEMFC) temperature management under stochastic disturbances, this paper integrates a PEMFC thermal model with a water pump model and establishes a nonlinear stochastic model for temperature regulation. The objective is to maintain the stack temperature at its optimal value. Due to the inherent complexity of the PEMFC electrochemical reactions, the thermal dynamics exhibit strong nonlinear characteristics. To tackle this issue, a control strategy based on the stochastic backstepping method is proposed. Furthermore, to cope with variations in membrane water content and ambient temperature during operation, we design stochastic estimator-based adaptive laws. Simulation results, considering both stochastic disturbances driven by tracking error and those driven by stack temperature and load current, indicate that the proposed control strategy effectively maintains the stack temperature at 343 K under various operating conditions, with a maximum deviation of 0.2 K, thereby confirming its effectiveness and robustness.

MSC:

93E15

1. Introduction

Hydrogen, as a clean energy carrier, has attracted worldwide attention. Fuel cells exhibit high efficiency in converting hydrogen into water and electrical energy [1]. Among them, the PEMFC is regarded as a promising power source for future transportation and related applications due to its high energy conversion efficiency, low environmental impact, and rapid start-up capability [2]. The stack temperature of the PEMFC is a critical factor affecting its performance and lifetime. Excessive temperature reduces the transport rate of reactants and the effective thickness of the catalyst layer. In contrast, insufficient temperature slows down the electrochemical reaction rate and may cause electrode flooding, preventing reactant gases from entering the electrodes and leading to voltage loss [3,4]. Therefore, efficient and stable thermal management is crucial to ensure the safe operation and prolong the service life of the PEMFC.

Numerous methods have been proposed for the temperature management of PEMFCs to enhance their performance and operational stability. Ahn et al. employed classical proportional and integral controllers and a state feedback control to suppress catalyst layer temperature rise and prevent oxygen starvation [5]. Hu et al. proposed a coolant circuit modeling method together with a temperature fuzzy control strategy to maintain PEMFC operation within the desired temperature range [6]. Kai Ou et al. developed a fuzzy logic controller with five inputs and two outputs to regulate the temperature and relative humidity of an open cathode fuel cell in real time, which effectively improved the output power of the PEMFC [7]. Hu et al. experimentally established the mapping relationship between the optimal operating temperature and PEMFC power and further designed a predictive controller with an optimal operating temperature tracking function to improve efficiency [8]. Chen et al. constructed a temperature management system model based on dual proportional–integral differential controllers and proposed an improved differential evolution algorithm to adjust the mutation factor, crossover factor, and search range, thereby maintaining the temperature difference between the cooling-water inlet and the stack at approximately 5 K [9]. Xu et al. proposed a temperature management strategy based on the sparrow search algorithm PID, which features fast convergence, good dynamic performance, and strong disturbance rejection capability, ensuring temperature fluctuations within 0.5 K under dynamic disturbance [10]. In addition to these model-based control strategies, data-driven approaches have also been explored for thermal management in complex energy systems. For instance, Brahim and Jemni investigated the thermal performance of flat miniature heat pipes using artificial neural network (ANN) models combined with experimental data. Their study demonstrated that ANN-based surrogate models can accurately predict key thermal parameters, such as maximum temperature and thermal resistance, under varying wick-fluid configurations and operating conditions [11]. Although these methods have achieved success in temperature regulation, most of them do not account for disturbances and parameter variations. Since PEMFCs are often subject to external disturbances, this raises more stringent requirements on controller robustness.

Han et al. designed a model reference adaptive feedback controller to address uncertainties and robustly regulate both the stack and coolant inlet temperatures of PEMFCs [12]. Li et al. regarded model uncertainties, external disturbances, and parameter variations as “total disturbance” to be estimated and compensated and proposed an active disturbance rejection control with a switching law [13]. Yan et al. designed the residual generator of sensor faults by Dulmage–Mendelsohn decomposition to rearrange the biadjacency matrix of the thermal model, thereby developing a sliding-mode-based active fault-tolerant control strategy for PEMFC thermal management [14]. Zang et al. addressed issues including erroneous control caused by sensor faults and strong nonlinearities induced by external current loading and proposed a fault-tolerant temperature control method based on an adaptive strong tracking Kalman filter combined with the Hampel algorithm, which significantly enhanced system stability [15]. These studies have made significant contributions to the temperature control of PEMFC stacks and to addressing parameter uncertainties and external disturbances. However, none of these works have considered the impact of stochastic disturbances on PEMFCs. In practical operating environments, stochastic disturbances can significantly affect PEMFC performance [16]. For example, stochastic disturbances in the load current influence the oxygen excess ratio [17], while stochastic disturbances in temperature affect the fuel cell voltage [18] and output power [19]. Therefore, it is essential to consider the impact of stochastic disturbances on the PEMFC; otherwise, its actual operational performance may degrade.

To address the aforementioned issues, this paper proposes an adaptive control strategy based on the stochastic backstepping method. The strategy accounts for multiple types of stochastic disturbances, including those driven by tracking error as well as by stack temperature and load current, and effectively stabilizes the stack temperature at its optimal value under both stochastic disturbances and parameter variations. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- A third-order nonlinear Itô stochastic model is established, which accounts for the influence of stochastic disturbances on the PEMFC stack temperature.

- Within the stochastic model framework, the stochastic estimator-based adaptive laws are designed to cope with variations in membrane water content and ambient temperature during operation, thereby enhancing the robustness of the system.

- A stochastic control law is developed to ensure that the stack temperature is maintained at its optimal value under multiple types of stochastic disturbances, while enhancing the robustness and performance of the controller.

- By combining the stochastic estimator-based adaptive laws with the stochastic control law, a stochastic parameter-variation-resistant control law is derived, thereby constructing a stochastic adaptive controller.

2. System Model and Problem Statement

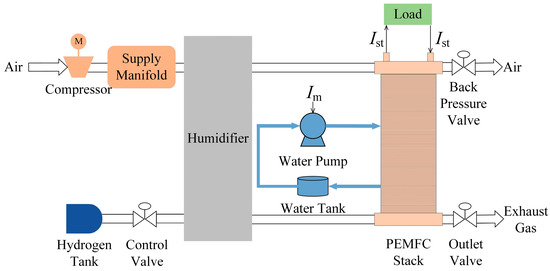

Figure 1 shows a schematic diagram of a PEMFC, which consists of the temperature management system, humidity management system, hydrogen supply system, and air supply system. This study focuses on the temperature management system. Based on the physics-based PEMFC thermal model [6] and the empirical water pump model [20], a third-order nonlinear Itô stochastic model for the PEMFC temperature management system is derived, as expressed in (1)–(3). The approach of combining these models has been previously applied in [21] for a deterministic system. It is assumed that the coolant temperature of the water pump is well controlled and the temperature of the coolant entering PEMFC remains constant. For simplicity of analysis, it is reasonably assumed that the pressures and inlet temperatures of the anode and cathode remain approximately equal during operation, , .

where . to are parameters of the water pump, which can be found in [20]. is an arbitrary function of and and is referred to as the diffusion term. Other parameters and functions in the proposed model are listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of PEMFC.

Table 1.

Expressions of parameters and functions in the proposed model (1)–(3).

The saturation vapor pressure according to vapor temperature is modeled as follows:

Under normal operating conditions, the PEMFC temperature typically ranges from 313 K to 373 K, with an optimal operating temperature of 343 K [6]. Therefore, the control objective of this paper is to regulate the stack temperature to 343 K. As shown in (1)–(4) and Table 1, the PEMFC temperature management system is a highly nonlinear system, which poses significant challenges for controller design. Moreover, the stack temperature is easily affected by variations in membrane water content [13], and this effect must be taken into account. In addition, considering that the PEMFC is commonly used in vehicles [22], the influence of ambient temperature variations is also considered in this study.

Remark 1.

The model proposed in this study combines the existing PEMFC thermal model and water pump model, with an additional diffusion term to account for stochastic disturbances. The focus is not on the modeling process itself, but rather on designing a control scheme based on the existing model under stochastic disturbances.

Remark 2.

The controller design of a stochastic system is more challenging than that of a deterministic one because of the Itô differential rule for the Lyapunov function, which leads to the emergence of the Itô correction term [23].

Remark 3.

Without loss of generality, we employ the arbitrary function to represent the diffusion terms of the Itô stochastic model (1)–(3). This design choice enhances the practical applicability of the proposed controller.

Remark 4.

Since this study only considers stochastic disturbances in the PEMFC thermal model, the diffusion term contains only . This also corresponds to the strict feedback form of the Itô stochastic differential equation, as detailed in [24].

Remark 5.

From Table 1, it can be observed that the expression of is highly nonlinear, and its partial derivative with respect to or is extremely complex. This increases the difficulty of controller implementation, thus necessitating the design of an estimator.

3. Main Results

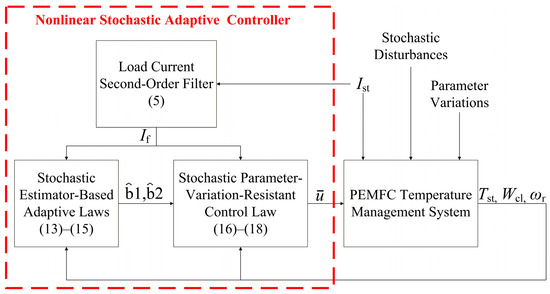

To address the problems presented in Section 2, a stochastic control law is designed in Section 3.1, and the stochastic estimator-based adaptive laws are developed in Section 3.2. By combining these two components, a stochastic parameter-variation-resistant control law is constructed in Section 3.3. The control law in Section 3.3, together with the stochastic adaptive laws, forms the proposed nonlinear stochastic adaptive controller. The overall control framework is illustrated in Figure 2. The stochastic control law described in Section 3.1 is not explicitly shown in Figure 2 because it has been integrated with the adaptive laws to form the stochastic parameter-variation-resistant control law.

Figure 2.

Diagram of the proposed control framework.

When the load current experiences a sudden change, its time derivative can produce a significant transient peak. In practical applications, PEMFC systems typically employ current limiters to ensure stable operation. Consequently, an auxiliary energy storage system is often integrated to buffer rapid variations in the load current [25]. In this paper, a load current second-order filter (5) is adopted to smooth the current input.

where is the filtered load current. and are time constants. In Section 3.1, Section 3.2 and Section 3.3, all are replaced with .

To enhance the practical applicability of the proposed adaptive laws, we consider the case where the diffusion term includes system parameters. In this paper, we focus on a class of stochastic systems in which the diffusion term is linear with respect to the system parameter and , and the arbitrary function is rewritten as follows:

where , and are arbitrary functions, and they do not include and .

3.1. Stochastic Control Law Design Based on Stochastic Backstepping Method

Definition 1.

Define the maximum function as follows:

where and denote arbitrary variables.

To maintain the PEMFC stack temperature at its optimal value in the presence of stochastic disturbances, a stochastic control law is designed based on the stochastic backstepping method proposed in [26]. Define , and . The proposed stochastic control law (8)–(10) is given as follows:

where , and are tunable parameters, and are small positive constants, and is a tunable parameter.

As stated in Remark 5, exhibits strong nonlinear characteristics, which make the analytical derivation of the derivative of highly complicated. Therefore, the following second-order tracking differentiator is employed for estimation:

where and are tunable parameters. and denote the estimated value and derivative of , respectively. The convergence and noise sensitivity analysis of the second-order tracking differentiator under stochastic disturbances are provided in Appendix B.

The remaining functions in the stochastic control law are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Expressions of functions in the stochastic control law (8)–(10).

The stochastic control law (8)–(10) can achieve the proposed control objective, and the proof is provided in Appendix C.

Remark 6.

Due to the strong nonlinearity of the PEMFC temperature management system, incorporating the stochastic disturbances in and into the design would significantly increase the complexity of the controller. Therefore, we neglect to ensure that the controller can be practically implemented while maintaining robustness against stochastic disturbances. Simulation results verify that this simplification is reasonable.

Remark 7.

Although this paper neglects the stochastic disturbance in and , the estimated value still includes the Itô correction term. This feature further enhances the system’s capability to resist stochastic disturbances.

Remark 8.

To analyze and address stochastic disturbances, the derivative of functions requires the application of Itô’s differential rule, which introduces an Itô correction term. This necessitates the design of a quartic Lyapunov function and the use of techniques such as Young’s inequality. These factors increase the design complexity and render the traditional backstepping method unsuitable for stochastic systems, thus requiring the development of a stochastic backstepping method. The Itô differential rule is presented in Appendix A.

3.2. Stochastic Estimator-Based Adaptive Laws Design for Parameter Variations

To address the variations in membrane water content and ambient temperature, the system parameters and , which are related to these factors, are selected as adaptive parameters. The proposed adaptive laws (13)–(15) are given as follows:

where , and are positive tunable parameters, and are small positive constants, and are the nominal values of and , and .

The stochastic estimator-based adaptive laws operate by automatically adjusting the adaptive parameters so that the estimated system states track the actual system states. After replacing the system parameters in the control law with the corresponding adaptive parameters, the estimated system, which is composed of the estimated and actual states, can achieve the desired control objective. Since the estimator shares the same structure as the actual system and the estimated states can track the actual ones, the estimated and actual systems can be regarded as equivalent. Therefore, the control law incorporating adaptive parameters enables the actual system to achieve the control objective while effectively addressing the problem of parameter variations.

The proposed stochastic adaptive laws (13)–(15) can automatically adjust the values of and , ensuring that converges to zero; for proof, see Appendix D.

Remark 9.

Similarly to the design of the stochastic control law (8)–(10), traditional adaptive control methods cannot be directly applied to stochastic systems. Moreover, the Itô correction term contains quadratic terms of the adaptive parameters, which must be properly handled.

Remark 10.

Although this study only considers variations in membrane water content and ambient temperature, leading to the selection of and as adaptive parameters, the proposed stochastic estimator-based adaptive law can be applied to design all system parameters in a stochastic system as adaptive parameters, with the design procedure remaining essentially unchanged. This facilitates future research and the improvement of disturbance-rejection performance, while significantly enhancing the practical applicability of the proposed stochastic adaptive controller.

3.3. Stochastic Parameter-Variation-Resistant Control Law Design

Definition 2.

For any variable or function , is the modified form of obtained by incorporating the adaptive laws (13)–(15), specifically by replacing and with and .

By integrating the stochastic control law (8)–(10) with the stochastic estimator-based adaptive laws (13)–(15), specifically by replacing and in (8)–(10) with and , the stochastic parameter-variation-resistant control law (16)–(18) is given as follows:

It is worth noting that the second-order tracking differentiator is modified as follows:

By combining (2), (3) and (13), a new PEMFC temperature management system is formed, which is referred to as the estimated system. Through the stochastic adaptive laws (13)–(15), in (13) will asymptotically converge to zero, which implies that the estimated system is equivalent to the actual system (1)–(3). Consequently, by replacing and in (8)–(10) with and , the resulting control law (16)–(18) ensures the closed-loop stability of the estimated system. Furthermore, since will asymptotically converge to zero, the proposed stochastic parameter-variation-resistant control law (16)–(18) ensures the closed-loop stability of the actual system, and thus the stochastic estimator-based adaptive laws (13)–(15) with the stochastic parameter-variation-resistant control law (16)–(18) guarantee that:

- Under stochastic disturbances, the stack temperature can rapidly and accurately track its optimal value;

- Under variations in membrane water content and ambient temperature, the stack temperature can still be maintained at its optimal value.

4. Simulation and Analysis of Results

To verify the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed controller, numerical simulations are carried out under two representative scenarios: (1) normal operation and (2) operation in the presence of parameter variations.

A conventional PID-based controller is designed for comparison with the proposed controller. Both controllers are implemented under identical system parameters to ensure a fair evaluation. The system parameters of PEMFC are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Parameters of PEMFC.

In both simulation scenarios, the PEMFC system is initially assumed to operate at steady state. The control gains of the proposed controller are chosen as and , . The parameters of the adaptive laws are set to , , , and . Meanwhile the PID controller parameters are set to , and . The time constants of the load current second-order filter (5) are configured as , . To verify the generality of the proposed controller, two types of diffusion terms under stochastic disturbances are considered: one driven by the tracking error and the other driven by the stack temperature and load current. The diffusion terms used in the simulations are as follows:

Multiple simulations are conducted for both cases. In the presented results, the light-colored curves represent individual simulation trajectories, while the dark-colored curves indicate the corresponding mean values. In addition, a shaded region with a lighter color denotes the fluctuation band, which covers 95% of the individual trajectories. All simulations are implemented in Python 3.12.6 using the SDEINT 0.3.1dev package.

4.1. Case 1: Normal Operation

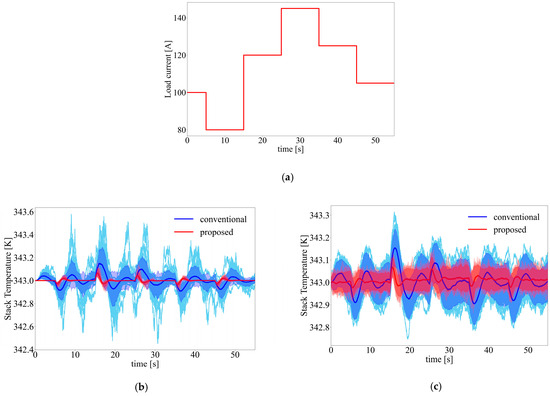

This subsection evaluates the controller’s capability to track the optimal operating temperature under variations in load current. The time evolution of the load current is illustrated in Figure 3a. In the simulations, a step function is employed to simulate the load current. This is because, in practical PEMFC applications, the load current often changes abruptly due to vehicle acceleration or equipment switching. The step function can effectively reproduce such sudden variations. Moreover, compared with smoothly varying signals, it provides a more rigorous test of the proposed controller’s performance and robustness.

Figure 3.

(a) Variation in the load current in case 1; (b) simulation result under stochastic disturbances driven by tracking error in case 1; and (c) simulation result under stochastic disturbances driven by stack temperature and load current in case 1.

Figure 3b compares the performance of the two controllers under stochastic disturbances driven by tracking error, while Figure 3c presents their performance under stochastic disturbances driven by stack temperature and load current. Due to the presence of stochastic disturbances, the results vary for each simulation run. Therefore, Figure 3b,c illustrate the outcomes obtained after 100 simulation runs to ensure the reliability of the simulations and to validate the practicality of the proposed controller.

As shown in Figure 3b,c, the red curve exhibits a markedly smaller temperature fluctuation amplitude than the blue one. From the fluctuation bands covering 95% of the trajectories, it can be observed that the red band is significantly narrower than the blue one. Moreover, under stochastic disturbances driven by tracking error, many trajectories of the conventional method clearly exceed the fluctuation band, indicating that the conventional controller experiences larger fluctuations under stochastic disturbances, whereas the proposed controller maintains smaller and more stable variations. Under stochastic disturbances driven by the tracking error, the conventional controller yields temperature oscillations of nearly 0.6 K, with a root mean square error (RMSE) of 0.060, a variance of 0.0041 and a maximum deviation of 0.580 K. In contrast, the proposed controller confines the fluctuation within 0.2 K, with an RMSE of 0.014, a variance of 0.0002 and a maximum deviation of 0.157 K, maintaining a stable and well-damped response.

When the system is subjected to stochastic disturbances driven by the stack temperature and load current, the conventional controller produces a fluctuation of approximately 0.3 K, with an RMSE of 0.063, a variance of 0.0494 and a maximum deviation of 0.315 K. The proposed controller further suppresses the variation to within 0.15 K, reducing the RMSE, variance and maximum deviation to 0.029, 0.0228 and 0.147 K, respectively. It exhibits faster convergence to the steady-state temperature, demonstrating superior transient performance and robustness against multiple types of stochastic disturbances.

Overall, the result demonstrates that, throughout the entire operation, the proposed controller not only provides stronger resistance to stochastic disturbances but also achieves faster and more stable tracking of the optimal operating temperature, confirming its excellent control performance and robustness.

Remark 11.

The results shown in Figure 3b,c indicate that the proposed controller significantly reduces the temperature fluctuation. This improvement can be mainly attributed to the treatment of the diffusion term in , as detailed in Appendix C, where the handling of the quartic Lyapunov function and the Itô correction term is elaborated. In addition, the second-order tracking differentiator (11)–(12) is employed to estimate the derivative of . The contribution of this estimation to mitigating stochastic disturbances has been discussed in Remark 7.

4.2. Case 2: Presence of Parameter Variations

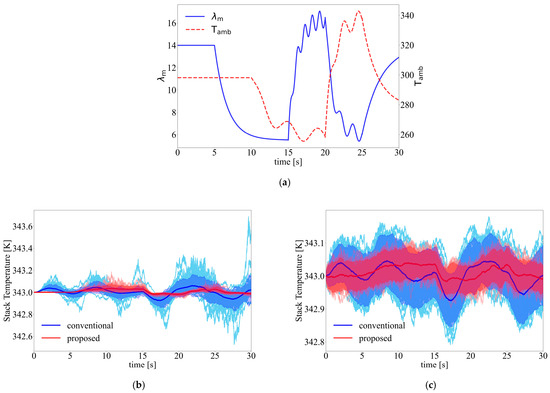

This subsection evaluates the controller’s capability to track the optimal operating temperature under parameter variations, including changes in and . The variations in these parameters are depicted in Figure 4a.

Figure 4.

(a) Variations in and in case 2; (b) simulation result under stochastic disturbances driven by tracking error in case 2; and (c) simulation result under stochastic disturbances driven by stack temperature and load current in case 2.

The stack temperature of the PEMFC has a significant impact on its performance and lifespan, while the system itself is susceptible to external disturbances [13,27]. Therefore, possessing strong disturbance-rejection capability is particularly important. Under conditions such as rapid load variations or abnormalities in the humidity control system, the membrane water content may fluctuate dramatically. In addition, since the PEMFC is often applied in mobile equipment such as vehicles, the ambient temperature may change rapidly when the vehicle moves from a garage to an outdoor environment or when heat dissipation becomes uneven. Hence, addressing the variations in membrane water content and ambient temperature is a crucial aspect for verifying the robustness and practical applicability of the proposed controller under complex operating conditions.

In Case 2, relatively smooth functions are used to simulate variations in membrane water content and environmental temperature to ensure physical realism, while relatively large amplitudes are chosen to evaluate the performance of the proposed controller under extreme operating conditions. Specifically, the membrane water content exhibits complex transient behavior: it remains at 14 initially, then rapidly decays to approximately 5.5 within the first 5 s, followed by a fast rise to 16.5 with small oscillations between 15 and 20 s, and subsequently decreases to 6 with damped oscillations from 20 to 25 s, finally returning gradually to 14. Meanwhile, the ambient temperature also varies dynamically: it stays at 298.15 K for the first 10 s, drops sharply to around 258.15 K with slight oscillations between 10 and 20 s, increases rapidly to about 338.15 K from 20 to 25 s with temperature inertia effects, and then slowly decreases to 278.15 K. These variations are designed to ensure physical realism while evaluating the proposed controller under extreme operating conditions.

The temperature tracking performances of both controllers under parameter variations are presented in Figure 4b,c. Similarly to Case 1, Figure 4b,c also illustrate the outcomes obtained after 100 simulation runs.

As shown in Figure 4b,c, the temperature represented by the red curve exhibits smaller fluctuations and faster convergence to the steady state. In addition, the fluctuation band is narrower, and the trajectories remain well within the band under stochastic disturbances driven by tracking error. Under stochastic disturbances driven by tracking error, the conventional controller exhibits temperature fluctuations of approximately 0.7 K, with an RMSE of 0.047, a variance of 0.0020 and a maximum deviation of 0.688 K. In contrast, the proposed controller limits the temperature variation within 0.2 K, with an RMSE of 0.021, a variance of 0.0004 and a maximum deviation of 0.187 K.

For stochastic disturbances driven by stack temperature and load current, the conventional controller results in temperature fluctuations of about 0.2 K, with an RMSE of 0.051, a variance of 0.00287 and a maximum deviation of 0.208 K. By comparison, the proposed controller effectively constrains the variation within 0.15 K, reducing the RMSE to 0.031, the variance to 0.00078 and the maximum deviation to 0.121 K, thereby ensuring a stable control response.

These observations indicate that the proposed controller can effectively handle parameter variations under stochastic disturbances and maintain stable system performance under complex operating conditions. Overall, the result highlights the significant potential of the controller for practical applications.

Remark 12.

During multiple numerical simulations, the traditional method occasionally exhibits divergence. To evaluate its average performance, the divergent simulation results of the traditional method are excluded. In contrast, no such exclusion is applied to the proposed method to ensure the reliability and practicality of the obtained conclusion.

5. Conclusions

This paper proposes a nonlinear stochastic adaptive controller for the PEMFC temperature management system, aiming to address two objectives under stochastic disturbances: (1) achieving fast and accurate tracking of the optimal operating temperature under varying load current conditions and (2) maintaining the optimal operating temperature in the presence of parameter variations. Specifically, by combining the PEMFC thermal model with the pump model, a third-order nonlinear Itô stochastic PEMFC temperature management model is established. To improve system robustness, stochastic estimator-based adaptive laws are designed, followed by the development of a stochastic control law using the stochastic backstepping method to achieve accurate temperature tracking. By integrating the adaptive laws with the control law, the proposed nonlinear stochastic adaptive controller is obtained. Numerical simulations are conducted to verify the effectiveness of the proposed controller. The complete model, controller design procedure, and parameter settings are provided to facilitate future research and practical applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.F.; methodology, Y.F.; software, Y.F. and Q.O.; validation, Y.F., Y.W. and Q.O.; formal analysis, Y.W. and Q.O.; investigation, Y.F.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.F.; writing—review and editing, Y.W.; project administration, Y.W. and Q.O.; funding acquisition, Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work of Yong Wan was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62173180.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in [ELSEVIER] at [10.1016/j.ijhydene.2010.06.046], reference number [6].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| Active area of cell | |

| Specific heat of hydrogen | |

| Specific heat of oxygen | |

| Specific heat of nitrogen | |

| Specific heat of air | |

| Specific heat of PEMFC | |

| Specific heat of liquid water | |

| Specific heat of gaseous water | |

| Membrane thickness | |

| Faraday constant | |

| Hydrogen combustion enthalpy | |

| PEMFC stack mass | |

| Number of cells in fuel cell stack | |

| Cathode pressure | |

| Anode pressure | |

| Thermal resistance | |

| Ambient temperature | |

| Cathode inlet gas temperature | |

| Anode inlet gas temperature | |

| Inlet chilling coolant temperature | |

| Standard temperature | |

| Hydrogen excess ratio | |

| Oxygen excess ratio | |

| Standard Wiener process | |

| Stack temperature of PEMFC | |

| Coolant flux | |

| Angular velocity of the coolant pump motor | |

| Input motor armature current of the coolant pump | |

| Load current | |

| Expected value of any variable | |

| Estimated value of any variable | |

| The first-order time derivative of any variable | |

| The second-order time derivative of any variable |

Appendix A

This appendix presents two fundamental and widely used mathematical lemmas that are essential for the analysis and derivations in this work. Specifically, we introduce the Itô differential theorem, which plays a central role in stochastic calculus and is instrumental in handling stochastic differential equations, and Young’s inequality, a classical inequality that provides useful bounds in various analytical contexts.

Lemma A1.

Consider the nonlinear stochastic system

where denotes the state vector. and denote locally Lipschitz functions and satisfy , . is the independent standard Wiener process. For any given twice continuously differentiable function , we can define the infinitesimal operator as follows:

where is the trace of a matrix and is referred to as the Itô correction term. If is negative definite, then the equilibrium of the system is globally asymptotically stable in probability. For proof, see reference [28].

Lemma A2.

There exist real numbers and , satisfying , and given ,

where . for proof, see reference [29].

Appendix B

Define , and . For simplicity of expression, , , and are denoted as , , and . Differentiating and replacing in and with yields

Define , , , . Differentiating and yields

where . The Lyapunov function is designed as follows:

The derivative of is given by

Then, according to Lemma A2, we obtain

Setting , we obtain

Substituting (A10) into (A8) yields

By adjusting the values of and , can be ensured, thereby verifying convergence.

Appendix C

Differentiating , and and replacing with yields

The Itô differential rule leads to the emergence of the Itô correction term, which necessitates the design of a quartic Lyapunov function. Therefore, the Lyapunov function is designed as follows:

According to Lemma A1 and Remark 6, by neglecting the diffusion terms in and , the derivative of is given by

Then, substituting and into (A16) yields

According to Lemma A2, the following inequalities can be derived:

Substituting (A18)–(A22) into (A17) yields

Thus, substituting (8)–(10) into (A23), when and , can yield

This proves that the designed stochastic control law can stabilize the stack temperature at its optimal value under stochastic disturbances.

Appendix D

By replacing with and subtracting (13) from (1), the dynamic of can be expressed as

The Lyapunov function is designed as follows:

According to Lemma A1, the derivative of is given by

and can be assumed to be constants and thus their derivatives are zero [30]. Therefore, and . Then, we can get

According to Lemma A2, the following inequality can be derived:

Subsequently, by substituting (A29) into (A28), we obtain

By applying Young’s inequality again, we obtain

Subsequently, by substituting (A31) and (A32) into (A30), we obtain

Then substituting (14) and (15) into (A33), we obtain

and mean the signs of and . Since the actual parameter values and cannot appear explicitly in the adaptive laws, and are replaced by and , which are used to approximate the sign functions and provide smoothing. In practical implementations, selecting a relatively large value for helps to attenuate the residual stochastic disturbances and enhance the system robustness.

References

- Lubitz, W.; Tumas, W. Hydrogen: An overview. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 3900–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisseune, H.; Willockx, A.; De Paepe, M. Semi-empirical along-the-channel model for a proton exchange membrane fuel cell. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2008, 33, 6270–6280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Sun, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z. Experimental analysis and optimal control of temperature with adaptive control objective for fuel cells. eTransportation 2024, 22, 100373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Lin, F.; Zhang, C.; Liao, R.; Wang, Y.-X. Design and implementation of model predictive control for an open-cathode fuel cell thermal management system. Renew. Energy 2020, 154, 1014–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.W.; Choe, S.Y. Coolant controls of a PEM fuel cell system. J. Power Sources 2008, 179, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Cao, G.; Zhu, X.; Hu, M. Coolant circuit modeling and temperature fuzzy control of proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 9110–9123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, K.; Yuan, W.-W.; Choi, M.; Yang, S.; Kim, Y.-B. Performance increase for an open-cathode PEM fuel cell with humidity and temperature control. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 29852–29862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, Q.; Wang, J. Investigation of optimal operating temperature for the PEMFC and its tracking control for energy saving in vehicle applications. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 249, 114842–114855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Feng, W.; You, S.; Hu, Y.; Wan, Y.; Zhao, B. Dual temperature parameter control of PEMFC stack based on improved differential evolution algorithm. Renew. Energy 2025, 241, 122319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.-H. Sparrow search algorithm applied to temperature control in PEM fuel cell systems. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 39973–39986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahim, T.; Jemni, A. Enhanced thermal performance analysis of flat miniature heat pipes using ANN and advanced wick-fluid configurations. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2026, 220, 110343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Yu, S.; Yi, S. Advanced thermal management of automotive fuel cells using a model reference adaptive control algorithm. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 4328–4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, C.; Gao, Z.; Jin, Q. On active disturbance rejection in temperature regulation of the proton exchange membrane fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2015, 283, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Chen, J.; Liu, H.; Lu, H. Model-based fault tolerant control for the thermal management of PEMFC systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 67, 2875–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yu, X.; Rubel, H.M.; Li, Q.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, S.; Wang, G. Fault-tolerant method of open-cathode PEMFC based on adaptive strong tracking Kalman filter combined with Hampel algorithm. Appl. Energy 2025, 388, 125570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, T. Active fault-tolerant coordination energy management for a proton exchange membrane fuel cell using curriculum-based multiagent deep metareinforcement learning. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 185, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Leal, A.P.; Palomo, F.R.; Barragán, F.; García, C.; Brey, J.J. Design of control systems for portable PEM fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2007, 169, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Placca, L.; Kouta, R.; Blachot, J.-F.; Charon, W. Effects of temperature uncertainty on the performance of a degrading PEM fuel cell model. J. Power Sources 2009, 194, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essalam, B.A.; Belkacem, O.B.; Aymen, K.Y.; Ramzi, K. A novel hybrid MPPT algorithm based on super twisting sliding mode and whale optimization algorithm for PEMFC systems. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Electrical Engineering, Automation and Control (ICEEAC), Setif, Algeria, 12–14 May 2024; Volume 2, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasu, G.; Tangirala, A. Control-orientated thermal model for proton-exchange membrane fuel cell systems. J. Power Sources 2008, 183, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.M.; Yoo, S.J. Approximation-based adaptive control of constrained uncertain thermal management systems with nonlinear coolant circuit dynamics of PEMFCs. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 83483–83494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, S.; Wang, Y.-X.; Xiao, X.; He, H.; Sun, F. Disturbance prediction-based enhanced stochastic model predictive control for hydrogen supply and circulating of vehicular fuel cells. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 238, 114167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, B.; Liu, X.; Liu, K.; Lin, C. Robust adaptive fuzzy tracking control for pure-feedback stochastic nonlinear systems with input constraints. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2013, 43, 2093–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.L.P.; Xie, S. Asymptotic fuzzy tracking control for a class of stochastic strict-feedback systems. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2017, 25, 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, F.; Gao, J. Oxygen excess ratio control of PEM fuel cells using observer-based nonlinear triple-step controller. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 29705–29717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Krstić, M. Stochastic nonlinear stabilization—I: A backstepping design. Syst. Control Lett. 1997, 32, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, H.C.; Zhang, A.; Mu, C.; Song, Y. Adaptive dynamic surface control with disturbance observer for oxygen-excess ratio of proton exchange membrane fuel cell systems. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Exp. Briefs 2025, 72, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasminskii, R. Stochastic Stability of Differential Equations; Springer: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Krstic, M.; Kanellakopoulos, I.; Kokotovic, P.V. Nonlinear and Adaptive Control Design; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, J.; Guo, Q.; Yue, M.; Diallo, D. A Lyapunov-based adaptive control strategy with fault-tolerant objectives for proton exchange membrane fuel cell air supply systems. Appl. Energy 2024, 376, 124275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).