Tri-Invariance Contrastive Framework for Robust Unsupervised Person Re-Identification

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We identify and formalize the problem of centroid misalignment between empirical cluster centroids and theoretical invariant centroids as a key bottleneck in unsupervised Re-ID.

- We propose ICCL, a novel framework that introduces center, instance, and camera invariance not as isolated components, but as a synergistic system to jointly address noise and camera variations, effectively bridging the centroid misalignment gap.

- The proposed unified framework integrates multiple invariance-based contrastive learning strategies, allowing the model to effectively leverage their combined strengths and resulting in a more robust solution for person re-identification.

- The method is tested on Market-1501, MSMT17 and CUHK03 datasets. The experimental results show that the method is effective and achieves good performance.

2. Related Work

2.1. Unsupervised Approaches for Person Re-ID

2.2. Contrastive Learning for Person Re-ID

2.3. Backbone Architectures in Vision Tasks

3. The Proposed Method

3.1. The Overall Framework

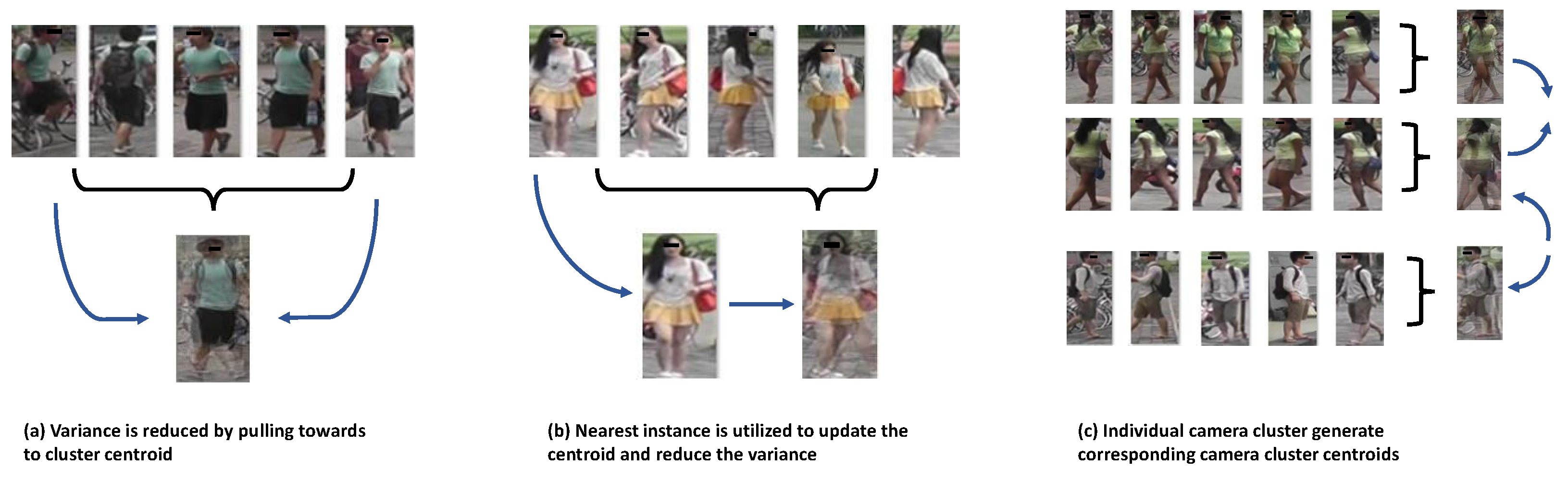

3.2. Center Invariance

3.3. Instance Invariance

3.4. Camera Invariance

3.5. Overall Loss of Invariance Learning

| Algorithm 1 Optimization procedure with invariance contrast learning |

Input: Unlabeled data captured Output: Optimized model F

|

4. Experiment

4.1. Datasets

4.2. Default Experimental Settings

4.3. Implementation Details

4.4. Comparison with Existing Methods

4.5. Ablation Study

4.6. Visualization Analysis of Model Predictions

4.7. Hyper-Parameter Analysis

- Sensitivity to . Figure 5 presents a quantitative analysis of sensitivity across three datasets. On Market-1501, the optimal mAP of 85.6% is achieved at , while Rank-1 accuracy reaches 92.1%. For MSMT17, the best performance (mAP: 31.1%, Rank-1: 60.5%) occurs at . CUHK03 shows a similar trend to MSMT17, with optimal results (mAP: 50.9%, Rank-1: 42.3%) at . This quantitative evidence confirms that MSMT17 and CUHK03, which are more complex datasets with greater camera variation, benefit from stronger camera invariance weighting compared to Market-1501.

- Sensitivity to Momentum . The effect of the momentum coefficient on model performance is systematically evaluated in Figure 6. Across all three datasets, the optimal value is consistently observed at , achieving a peak performance of 85.6% mAP and 92.1% Rank-1 on Market-1501, 31.1% mAP and 60.5% Rank-1 on MSMT17, and 50.9% mAP and 42.3% Rank-1 on CUHK03. Performance degradation is observed when deviates from this optimal value, particularly when , demonstrating the importance of balanced momentum for stable memory updates.

- Sensitivity to the number of epochs. Figure 7 illustrates the convergence behavior across datasets. Market-1501 reaches peak performance at epoch 60 (mAP: 85.6%, Rank-1: 92.1%) with slight degradation thereafter, indicating potential overfitting. In contrast, MSMT17 shows continuous improvement throughout the 80-epoch training process, achieving final scores of 31.1% mAP and 60.5% Rank-1. CUHK03 demonstrates intermediate behavior, stabilizing around epoch 70 with final performance of 50.9% mAP and 42.3% Rank-1.

4.8. Computational Complexity

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Hu, H.; Chen, D.; Su, T. Deeply Associative Two-Stage Representations Learning Based on Labels Interval Extension Loss and Group Loss for Person Re-Identification. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2020, 30, 4526–4539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Qi, G.; Jiang, R.; Jin, Z.; Yong, H.; Chen, Y.; Hua, X. Sharp Attention Network via Adaptive Sampling for Person Re-Identification. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2019, 29, 3016–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhao, H.; Yin, G.; Yi, S.; Wang, X.; Li, H. FD-GAN: Pose-guided Feature Distilling GAN for Robust Person Re-identification. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 31: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2018, NeurIPS 2018, Montréal, QC, Canada, 3–8 December 2018; Bengio, S., Wallach, H.M., Larochelle, H., Grauman, K., Cesa-Bianchi, N., Garnett, R., Eds.; NeurIPS: San Diego, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 1230–1241. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, Y.; Lu, S.; Ye, Q.; Shan, X.; Chen, J.; Ji, R.; Tian, Y. AD-Cluster: Augmented Discriminative Clustering for Domain Adaptive Person Re-Identification. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2020, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; Computer Vision Foundation/IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 9018–9027. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, S.; Yang, M. Self-Guided Hash Coding for Large-Scale Person Re-identification. In Proceedings of the 2nd IEEE Conference on Multimedia Information Processing and Retrieval, MIPR 2019, San Jose, CA, USA, 28–30 March 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 246–251. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H.; Jiang, W.; Gu, Y.; Liu, F.; Liao, X.; Lai, S.; Gu, J. A Strong Baseline and Batch Normalization Neck for Deep Person Re-Identification. IEEE Trans. Multim. 2020, 22, 2597–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Fan, H.; Xu, M.; Yang, Y. Adaptive Exploration for Unsupervised Person Re-identification. ACM Trans. Multim. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2020, 16, 3:1–3:19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhu, X.; Gong, S. Instance-Guided Context Rendering for Cross-Domain Person Re-Identification. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2019, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 232–242. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Xie, L.; Wu, Y.; Yan, C.; Tian, Q. Unsupervised Person Re-Identification via Softened Similarity Learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2020, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; Computer Vision Foundation/IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 3387–3396. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, K.; Ning, M.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Y. Hierarchical Clustering With Hard-Batch Triplet Loss for Person Re-Identification. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2020, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; Computer Vision Foundation/IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 13654–13662. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.G.; Chen, S.C.; Hwang, J.N.; Hung, Y.P. An ensemble of invariant features for person reidentification. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2016, 27, 470–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, H.; Lin, W.; Chandran, A.K.; Jing, X. Camera contrast learning for unsupervised person re-identification. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 33, 4096–4107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Kim, W.J.; Hong, S.; Yoon, S.E. Part-based pseudo label refinement for unsupervised person re-identification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–20 June 2022; pp. 7308–7318. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Z.; Wang, G.; Zhu, S.; Yuan, W.; Tan, P. Cluster Contrast for Unsupervised Person Re-Identification. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.11568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, D.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Ding, E.; Shi, J.Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J. Implicit sample extension for unsupervised person re-identification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–20 June 2022; pp. 7369–7378. [Google Scholar]

- Ester, M.; Kriegel, H.; Sander, J.; Xu, X. A Density-Based Algorithm for Discovering Clusters in Large Spatial Databases with Noise. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD-96), Portland, OR, USA, 2–4 August 1996; Simoudis, E., Han, J., Fayyad, U.M., Eds.; AAAI Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 226–231. [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, K.I. Proceedings of the fifth Berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1969, 21, 407. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Y.; Zhu, F.; Chen, D.; Zhao, R.; Li, H. Self-paced Contrastive Learning with Hybrid Memory for Domain Adaptive Object Re-ID. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, NeurIPS 2020, Virtual, 6–12 December 2020; Larochelle, H., Ranzato, M., Hadsell, R., Balcan, M., Lin, H., Eds.; NeurIPS: San Diego, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Zhu, X.; Xiang, T.; Gong, S. Towards unsupervised open-set person re-identification. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing, ICIP 2016, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 25–28 September 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 769–773. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Lagadec, B.; Brémond, F. ICE: Inter-instance Contrastive Encoding for Unsupervised Person Re-identification. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2021, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 14940–14949. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Lai, B.; Huang, J.; Gong, X.; Hua, X. Camera-Aware Proxies for Unsupervised Person Re-Identification. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Fifth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, AAAI 2021, Thirty-Third Conference on Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence, IAAI 2021, the Eleventh Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence, EAAI 2021, Virtual Event, 2–9 February 2021; AAAI Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2021; pp. 2764–2772. [Google Scholar]

- Hermans, A.; Beyer, L.; Leibe, B. In Defense of the Triplet Loss for Person Re-Identification. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1703.07737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroff, F.; Kalenichenko, D.; Philbin, J. FaceNet: A unified embedding for face recognition and clustering. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2015, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; IEEE Computer Society: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 815–823. [Google Scholar]

- Oord, A.; Li, Y.; Vinyals, O. Representation Learning with Contrastive Predictive Coding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.03748. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, S. Unsupervised Person Re-Identification via Multi-Label Classification. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2020, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; Computer Vision Foundation/IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 10978–10987. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Y.; Chen, D.; Li, H. Mutual Mean-Teaching: Pseudo Label Refinery for Unsupervised Domain Adaptation on Person Re-identification. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2020, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 26–30 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, L.; Zhang, S.; Gao, W.; Tian, Q. Person Transfer GAN to Bridge Domain Gap for Person Re-Identification. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2018, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; Computer Vision Foundation/IEEE Computer Society: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, W.; Zheng, L.; Ye, Q.; Kang, G.; Yang, Y.; Jiao, J. Image-Image Domain Adaptation With Preserved Self-Similarity and Domain-Dissimilarity for Person Re-Identification. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2018, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; Computer Vision Foundation/IEEE Computer Society: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 994–1003. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Z.; Zheng, L.; Luo, Z.; Li, S.; Yang, Y. Invariance Matters: Exemplar Memory for Domain Adaptive Person Re-Identification. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2019, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019; Computer Vision Foundation/IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 598–607. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Lin, C.; Lin, Y.; Wang, Y.F. Cross-Dataset Person Re-Identification via Unsupervised Pose Disentanglement and Adaptation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2019, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 7918–7928. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Harandi, M.; Jin, X.; Yang, X. Domain Adaptation by Joint Distribution Invariant Projections. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 29, 8264–8277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Cao, J.; Shen, C.; You, M. Self-Training With Progressive Augmentation for Unsupervised Cross-Domain Person Re-Identification. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2019, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 8221–8230. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Y.; Zhu, F.; Zhao, R.; Li, H. Structured Domain Adaptation with Online Relation Regularization for Unsupervised Person Re-ID. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2020, 35, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, S. Domain Adaptive Person Re-Identification via Coupling Optimization. In Proceedings of the MM ’20: The 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Virtual Event, Seattle, WA, USA, 12–16 October 2020; Chen, C.W., Cucchiara, R., Hua, X., Qi, G., Ricci, E., Zhang, Z., Zimmermann, R., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 547–555. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X.; Lan, C.; Zeng, W.; Chen, Z. Global Distance-Distributions Separation for Unsupervised Person Re-identification. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision-ECCV 2020-16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020, Proceedings, Part VII; Vedaldi, A., Bischof, H., Brox, T., Frahm, J., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 12352, pp. 735–751. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.; Wei, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, H.; Huang, T.S. Self-Similarity Grouping: A Simple Unsupervised Cross Domain Adaptation Approach for Person Re-Identification. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2019, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 6111–6120. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, H.; Zheng, L.; Yan, C.; Yang, Y. Unsupervised Person Re-identification: Clustering and Fine-tuning. ACM Trans. Multim. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2018, 14, 83:1–83:18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Dong, X.; Zheng, L.; Yan, Y.; Yang, Y. A Bottom-Up Clustering Approach to Unsupervised Person Re-Identification. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Third AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, AAAI 2019, the Thirty-First Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference, IAAI 2019, the Ninth AAAI Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence, EAAI 2019, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 January–1 February 2019; AAAI Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 8738–8745. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, F.; Liao, S.; Xie, G.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, K.; Shao, L. Unsupervised Domain Adaptation with Noise Resistible Mutual-Training for Person Re-identification. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision-ECCV 2020-16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020, Proceedings, Part XI; Vedaldi, A., Bischof, H., Brox, T., Frahm, J., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 12356, pp. 526–544. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiang, T.; Hospedales, T.M.; Lu, H. Deep Mutual Learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2018, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; Computer Vision Foundation/IEEE Computer Society: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 4320–4328. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Y.; Sharma, G. Cross-modality hierarchical clustering and refinement for unsupervised visible-infrared person re-identification. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 34, 2706–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Chen, J.; Ye, M. Towards grand unified representation learning for unsupervised visible-infrared person re-identification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–3 October 2023; pp. 11069–11079. [Google Scholar]

- Grill, J.; Strub, F.; Altché, F.; Tallec, C.; Richemond, P.H.; Buchatskaya, E.; Doersch, C.; Pires, B.Á.; Guo, Z.; Azar, M.G.; et al. Bootstrap Your Own Latent—A New Approach to Self-Supervised Learning. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, NeurIPS 2020, Virtual, 6–12 December 2020; Larochelle, H., Ranzato, M., Hadsell, R., Balcan, M., Lin, H., Eds.; NeurIPS: San Diego, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Kornblith, S.; Norouzi, M.; Hinton, G.E. A Simple Framework for Contrastive Learning of Visual Representations. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2020, Virtual Event, 13–18 July 2020; Proceedings of Machine Learning Research. PMLR: Birmingham, UK, 2020; Volume 119, pp. 1597–1607. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Fan, H.; Wu, Y.; Xie, S.; Girshick, R.B. Momentum Contrast for Unsupervised Visual Representation Learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2020, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; Computer Vision Foundation/IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 9726–9735. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Park, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, J. Safety helmet monitoring on construction sites using YOLOv10 and advanced transformer architectures with surveillance and body-worn cameras. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2025, 151, 04025186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Automated non-PPE detection on construction sites using YOLOv10 and transformer architectures for surveillance and body worn cameras with benchmark datasets. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2016, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; IEEE Computer Society: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.; Shen, L.; Tian, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Tian, Q. Scalable Person Re-identification: A Benchmark. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2015, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; IEEE Computer Society: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1116–1124. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Chintala, S.; Chanan, G.; Yang, E.; Devito, Z.; Lin, Z.; Desmaison, A.; Antiga, L.; Lerer, A. Automatic differentiation in PyTorch. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Liu, H.; Yang, Y.; Lei, Z.; Liao, S.; Li, S.Z. Unsupervised Graph Association for Person Re-Identification. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2019, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 8320–8329. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Zhu, X.; Gong, S. Unsupervised Person Re-identification by Deep Learning Tracklet Association. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision-ECCV 2018-15th European Conference, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018, Proceedings, Part IV; Ferrari, V., Hebert, M., Sminchisescu, C., Weiss, Y., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 11208, pp. 772–788. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Zhu, X.; Gong, S. Unsupervised tracklet person re-identification. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2019, 42, 1770–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Y.; Ye, Q.; Lu, S.; Jia, M.; Ji, R.; Tian, Y. Multiple expert brainstorming for domain adaptive person re-identification. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Online, 23–28 August 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 594–611. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, L.; Wang, L.; Huo, J.; Zhou, L.; Shi, Y.; Gao, Y. A Novel Unsupervised Camera-Aware Domain Adaptation Framework for Person Re-Identification. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2019, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 8079–8088. [Google Scholar]

| Dataset | Object | #Train IDs | #Train Images | #Test IDs | #Query Images | #Total Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market-1501 | Person | 751 | 12,936 | 750 | 3368 | 32,668 |

| MSMT17 | Person | 1041 | 32,621 | 3060 | 11,659 | 126,441 |

| Component | Configuration/Value |

|---|---|

| Backbone | ResNet-50 [48] |

| Input Size | |

| Batch Size | 256 (comprising 16 distinct identities × 16 instances per identity) |

| Optimizer | Adam (weight decay ) |

| Learning Rate | , kept constant throughout training |

| Training Epochs | Market-1501: 60, MSMT17: 80 |

| Data Augmentation | Random horizontal flipping, 10-pixel padding, random cropping, random erasing |

| Loss Weights | , , |

| Clustering Algorithm | DBSCAN (eps = 0.6, min_samples = 4) |

| Memory Momentum () | 0.2 |

| Method | Market1501 | MSMT17 | CUHK03 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mAP | Rank-1 | Rank-5 | Rank-10 | mAP | Rank-1 | Rank-5 | Rank-10 | mAP | Rank-1 | Rank-5 | Rank-10 | |

| Fully unsupervised | ||||||||||||

| BUC [6] | 38.3 | 66.2 | 79.6 | 84.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| SSL [9] | 37.8 | 71.7 | 83.8 | 87.4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| MMCL [25] | 45.5 | 80.3 | 89.4 | 92.3 | 11.2 | 35.4 | 44.8 | 49.8 | - | - | - | - |

| HCT [10] | 56.4 | 80.0 | 91.6 | 95.0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| CycAs | 64.8 | 84.8 | - | - | 26.7 | 50.1 | - | - | 47.4 | 41.0 | - | - |

| UGA [51] | 70.3 | 87.2 | - | - | 21.7 | 49.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| SPCL/Infomap | 70.7 | 86.3 | 93.6 | 95.6 | 17.2 | 40.6 | 53.6 | 59.2 | - | - | - | - |

| SPCL [18] | 73.1 | 88.1 | 95.1 | 97.0 | 19.1 | 42.3 | 55.6 | 61.2 | - | - | - | - |

| TAUDL [52] | - | - | - | - | 12.5 | 28.4 | - | - | 44.7 | 31.2 | - | - |

| Cluster contrast [14] | 82.1 | 92.3 | 96.7 | 97.9 | 27.6 | 56.0 | 66.8 | 71.5 | - | - | - | - |

| ICE [20] | 79.5 | 92.0 | 97.0 | 98.1 | 29.8 | 59.0 | 71.7 | 77.0 | - | - | - | - |

| Ours | 85.6 | 92.1 | 97.3 | 98.2 | 31.1 | 60.5 | 70.9 | 77.6 | 50.9 | 42.3 | 45.7 | 49.1 |

| Domain adaptive | ||||||||||||

| UTAL [53] | - | - | - | - | 13.1 | 31.4 | - | - | 56.3 | 42.3 | - | - |

| MMCL [25] | 60.4 | 84.4 | 92.8 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ECN [29] | - | - | - | - | 10.2 | 30.2 | 41.5 | 46.8 | - | - | - | - |

| AD-Cluster++ [4] | 68.3 | 86.7 | 94.4 | 96.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| MMT [26] | 75.6 | 89.3 | 95.8 | 97.5 | 24.0 | 50.1 | 63.5 | 69.3 | - | - | - | - |

| SPCL [18] | 77.5 | 89.7 | 96.1 | 97.6 | 26.8 | 53.7 | 65.0 | 69.8 | - | - | - | - |

| MEB-Net [54] | 76.0 | 89.9 | 96.0 | 97.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Method | Market1501 | MSMT17 | CUHK03 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mAP | Rank-1 | Rank-5 | Rank-10 | mAP | Rank-1 | Rank-5 | Rank-10 | mAP | Rank-1 | Rank-5 | Rank-10 | |

| ICCL w/ | 78.1 | 90.5 | 93.9 | 95.8 | 23.1 | 53.8 | 62.1 | 68.1 | 42.1 | 36.8 | 39.7 | 42.9 |

| ICCL w/ | 80.1 | 91.6 | 94.8 | 98.1 | 23.2 | 55.8 | 66.5 | 69.3 | 46.7 | 39.1 | 41.5 | 47.2 |

| ICCL w/ | 85.6 | 92.1 | 97.3 | 98.2 | 31.1 | 60.5 | 70.9 | 77.6 | 50.9 | 42.3 | 45.7 | 49.1 |

| Methods | Setting | Time (s/ep) | GPU (GB) | Params (M) | Rank-1 | mAP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BUC [55] | USL | 110 | 3.5 | 12.3 | 66.2 | 38.3 |

| MMCL [25] | USL | 135 | 4.1 | 12.3 | 80.3 | 45.5 |

| SPCL [18] | UDA | 140 | 4.3 | 12.3 | 89.7 | 77.5 |

| Cluster Contrast [14] | USL | 125 | 3.8 | 12.3 | 92.3 | 82.1 |

| ICCL (Ours) | USL | 128 | 4.0 | 12.3 | 93.9 | 85.3 |

| Method | Dataset | FPS ↑ | Latency (ms) ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPCL [18] | Market-1501 | 110 | 9.1 |

| Cluster Contrast [14] | Market-1501 | 118 | 8.4 |

| ICCL (Ours) | Market-1501 | 124 | 8.1 |

| Cluster Contrast [14] | MSMT17 | 110 | 9.1 |

| ICCL (Ours) | MSMT17 | 117 | 8.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Gao, W.; Ge, X.; Zhu, S. Tri-Invariance Contrastive Framework for Robust Unsupervised Person Re-Identification. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3570. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13213570

Wang L, Liu C, Wang X, Gao W, Ge X, Zhu S. Tri-Invariance Contrastive Framework for Robust Unsupervised Person Re-Identification. Mathematics. 2025; 13(21):3570. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13213570

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Lei, Chengang Liu, Xiaoxiao Wang, Weidong Gao, Xuejian Ge, and Shunjie Zhu. 2025. "Tri-Invariance Contrastive Framework for Robust Unsupervised Person Re-Identification" Mathematics 13, no. 21: 3570. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13213570

APA StyleWang, L., Liu, C., Wang, X., Gao, W., Ge, X., & Zhu, S. (2025). Tri-Invariance Contrastive Framework for Robust Unsupervised Person Re-Identification. Mathematics, 13(21), 3570. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13213570