Robust Bias Compensation LMS Algorithms Under Colored Gaussian Input Noise and Impulse Observation Noise Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A novel bias compensation method is developed, specifically designed to address colored Gaussian input noise, which has not been adequately tackled by existing techniques that typically assume white Gaussian input noise.

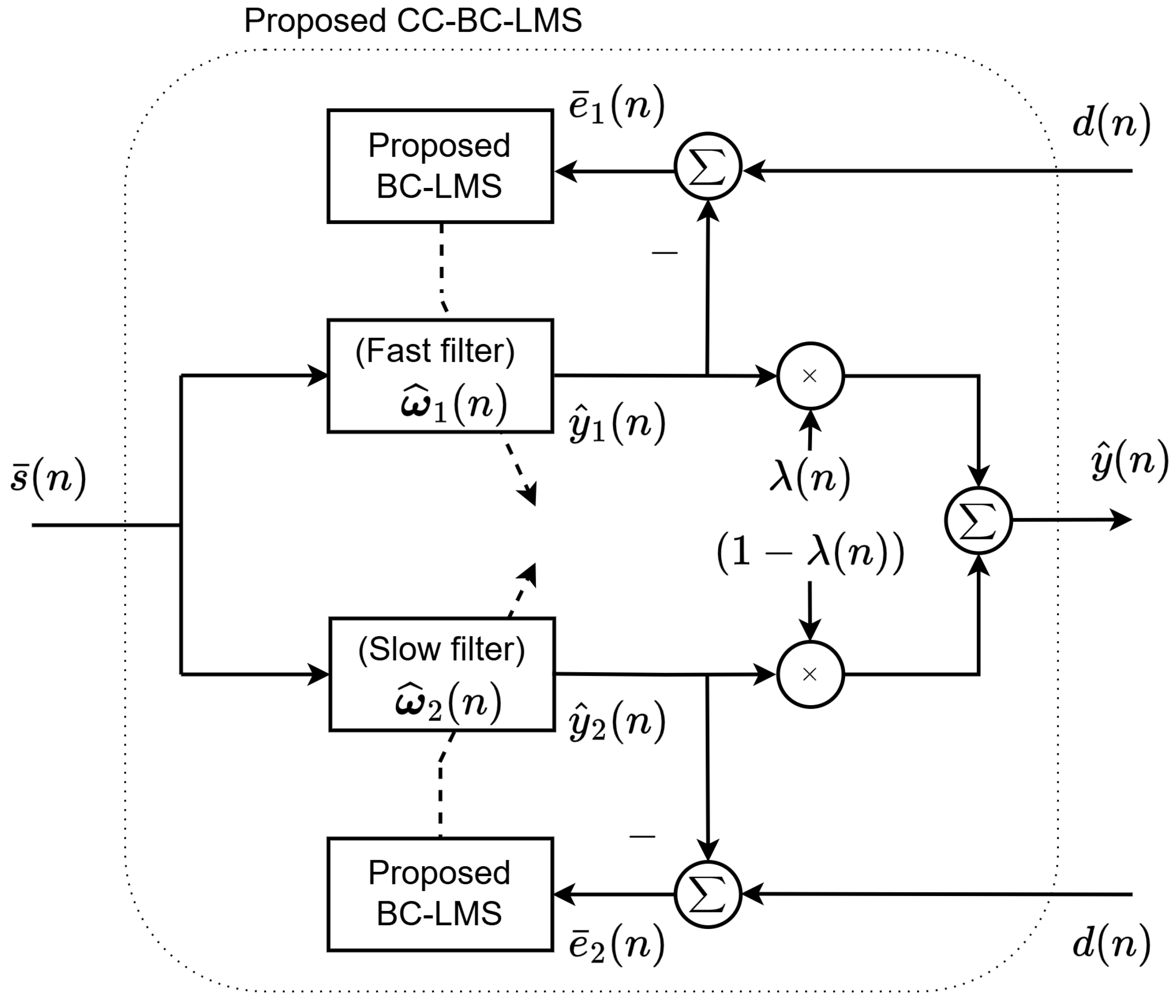

- The proposed convex-combined bias compensation LMS (CC-BC-LMS) algorithm employs a dynamic combination of fast and slow adaptive filters, using a soft-switching mechanism to achieve variable step-size adaptation. This enables a balance between rapid convergence (by the fast filter) and low steady-state error (via the slow filter), resulting in robust tracking and precision in challenging noise environments.

- A modified Huber function is integrated into the error estimation process, which improves the resilience of the algorithm to impulsive observation noise, further expanding its applicability to real-world sensor and communication systems experiencing both input and observation noise.

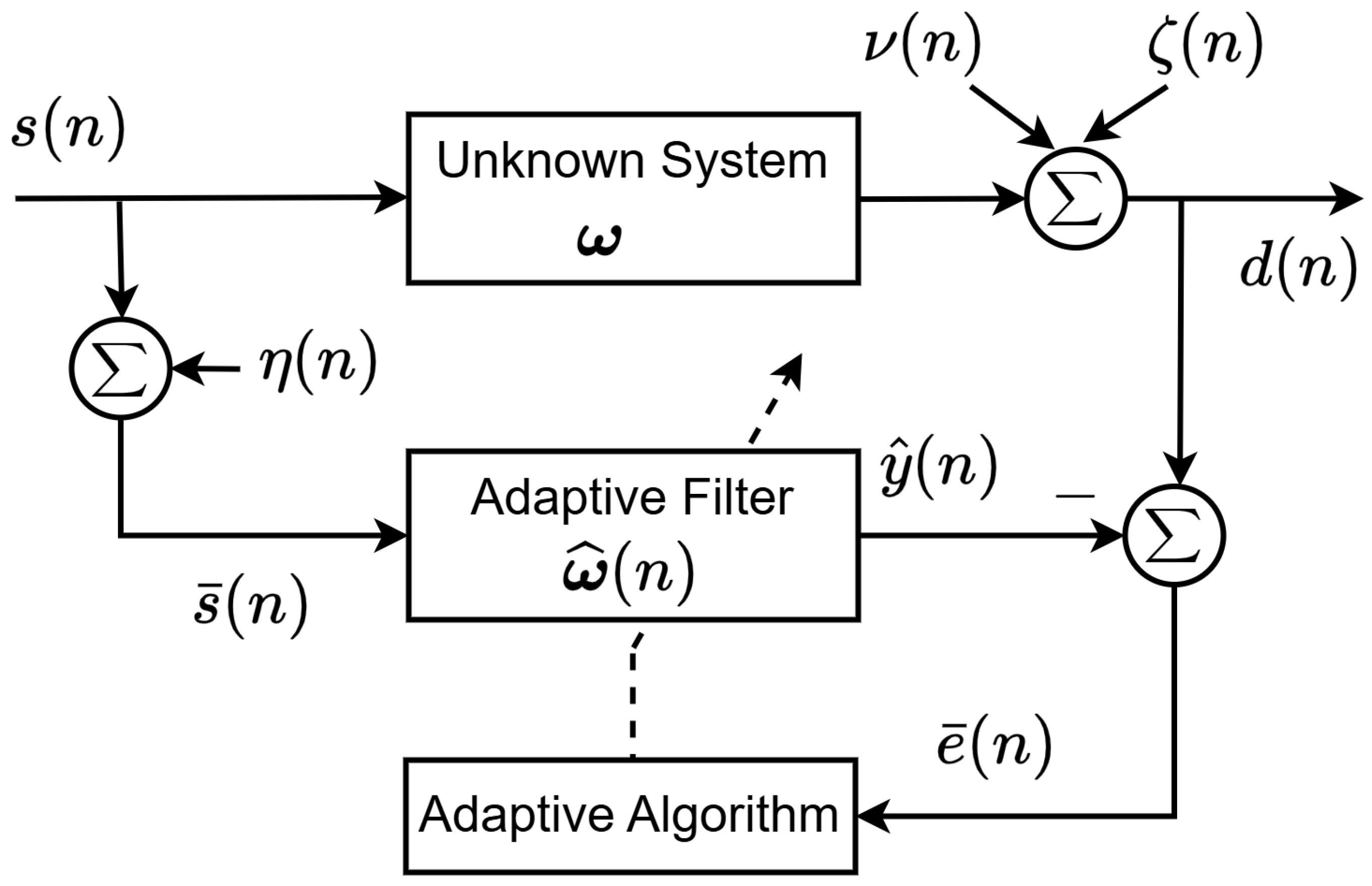

2. System Models

3. Proposed Method

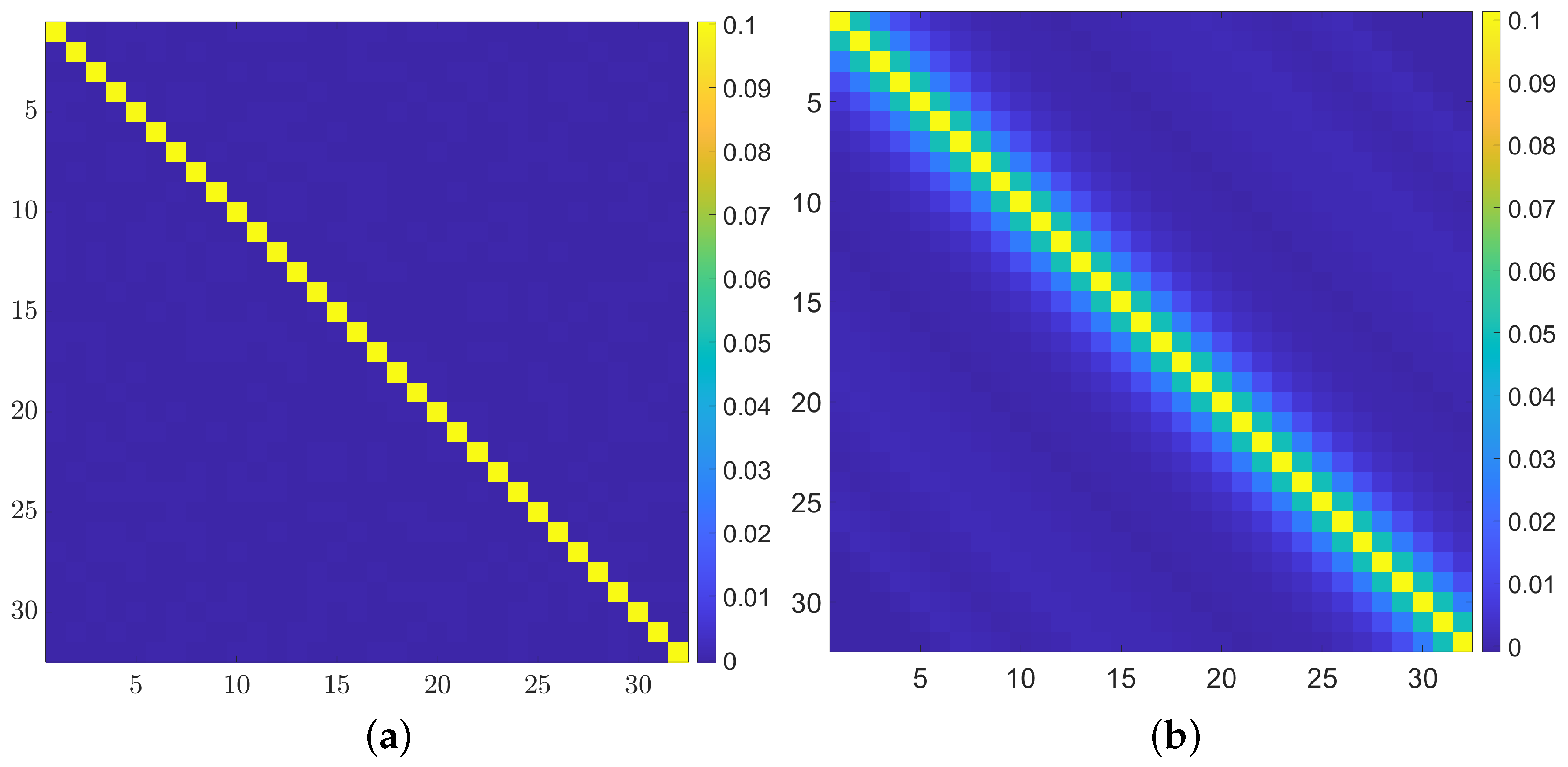

3.1. Considerations for Robust Operation

3.2. Variable Step-Size by Convex Combination

3.3. Mean Stability Analysis

3.4. Computational Complexity Analysis

4. Simulation Results

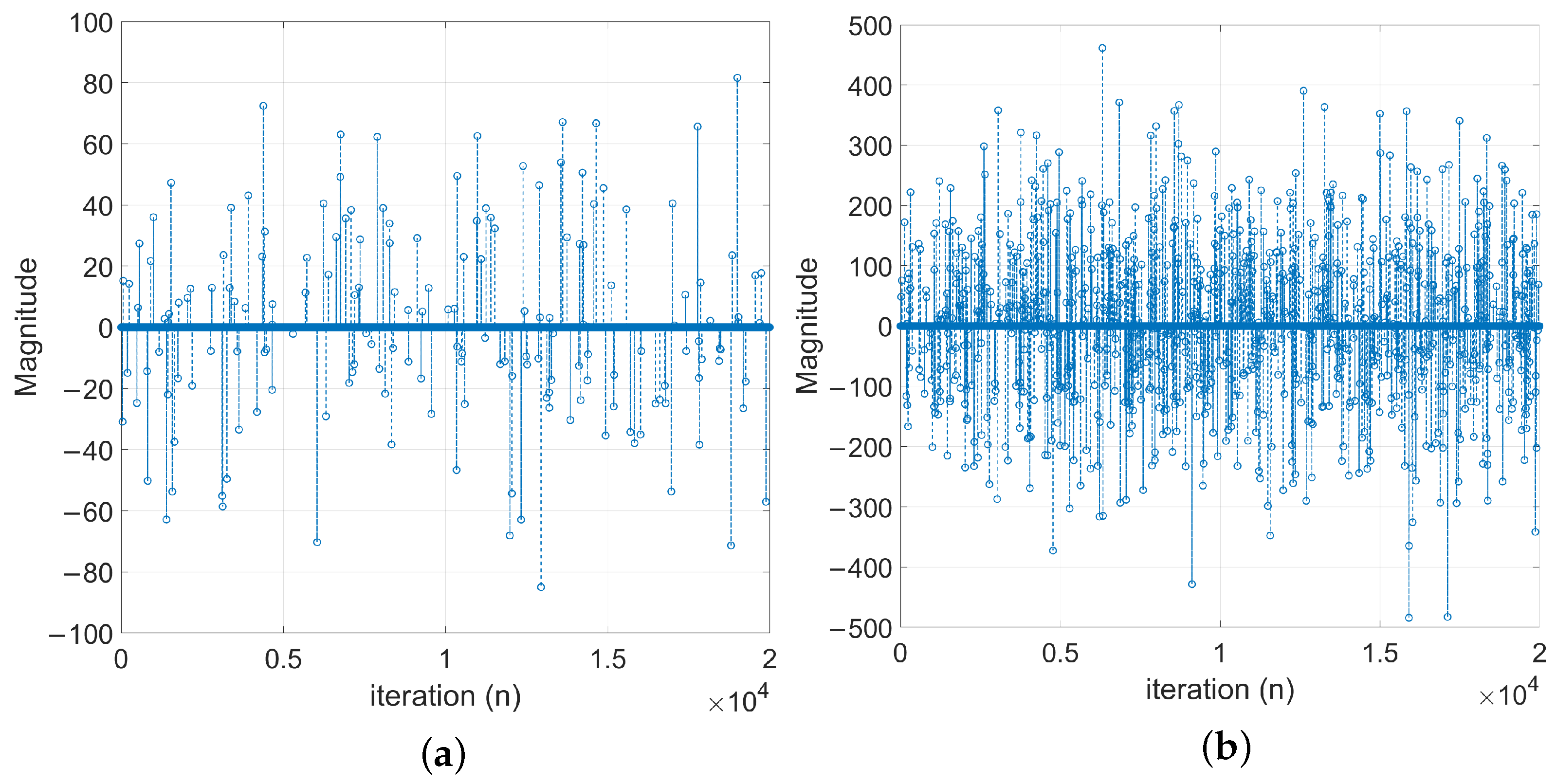

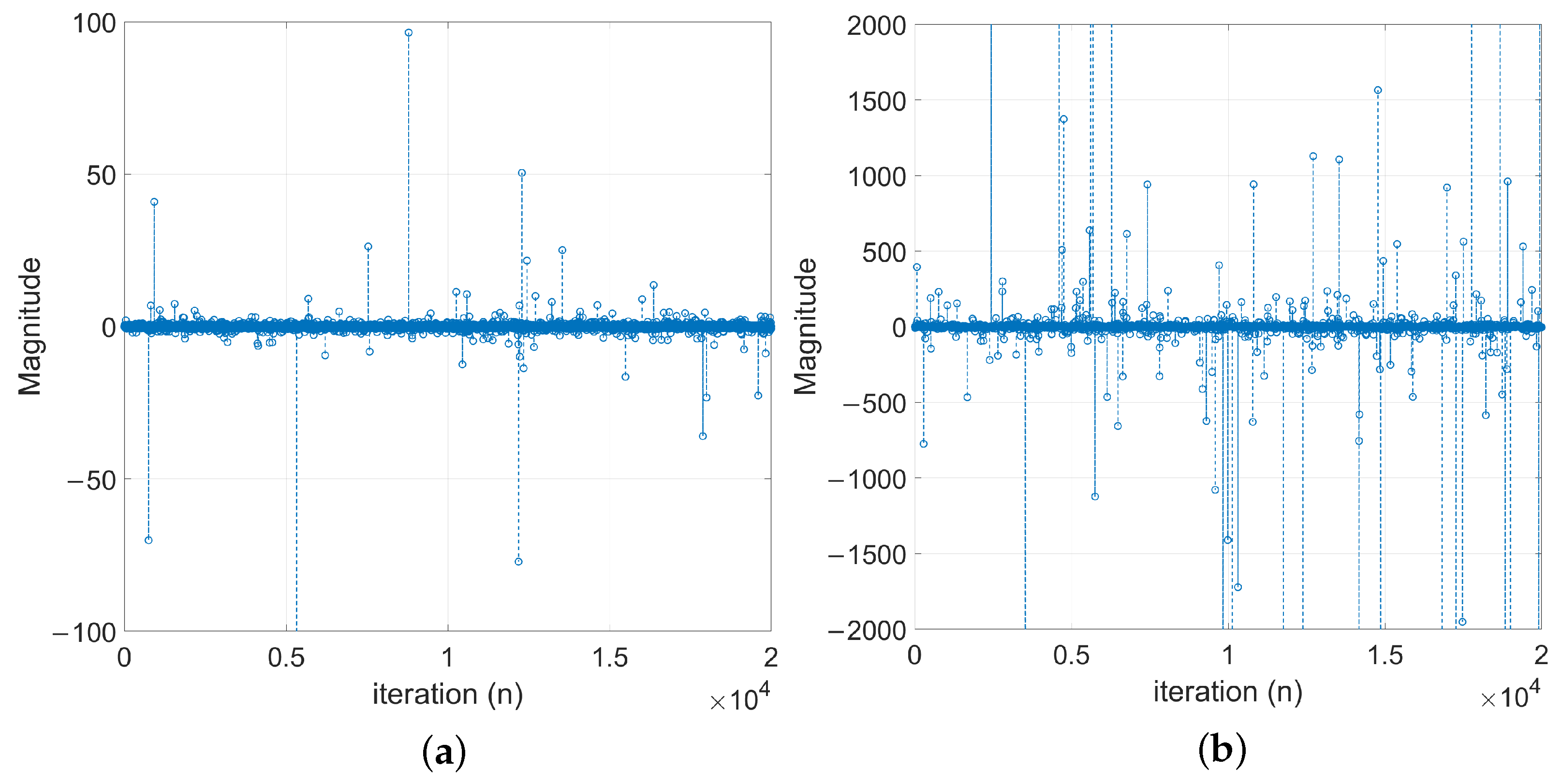

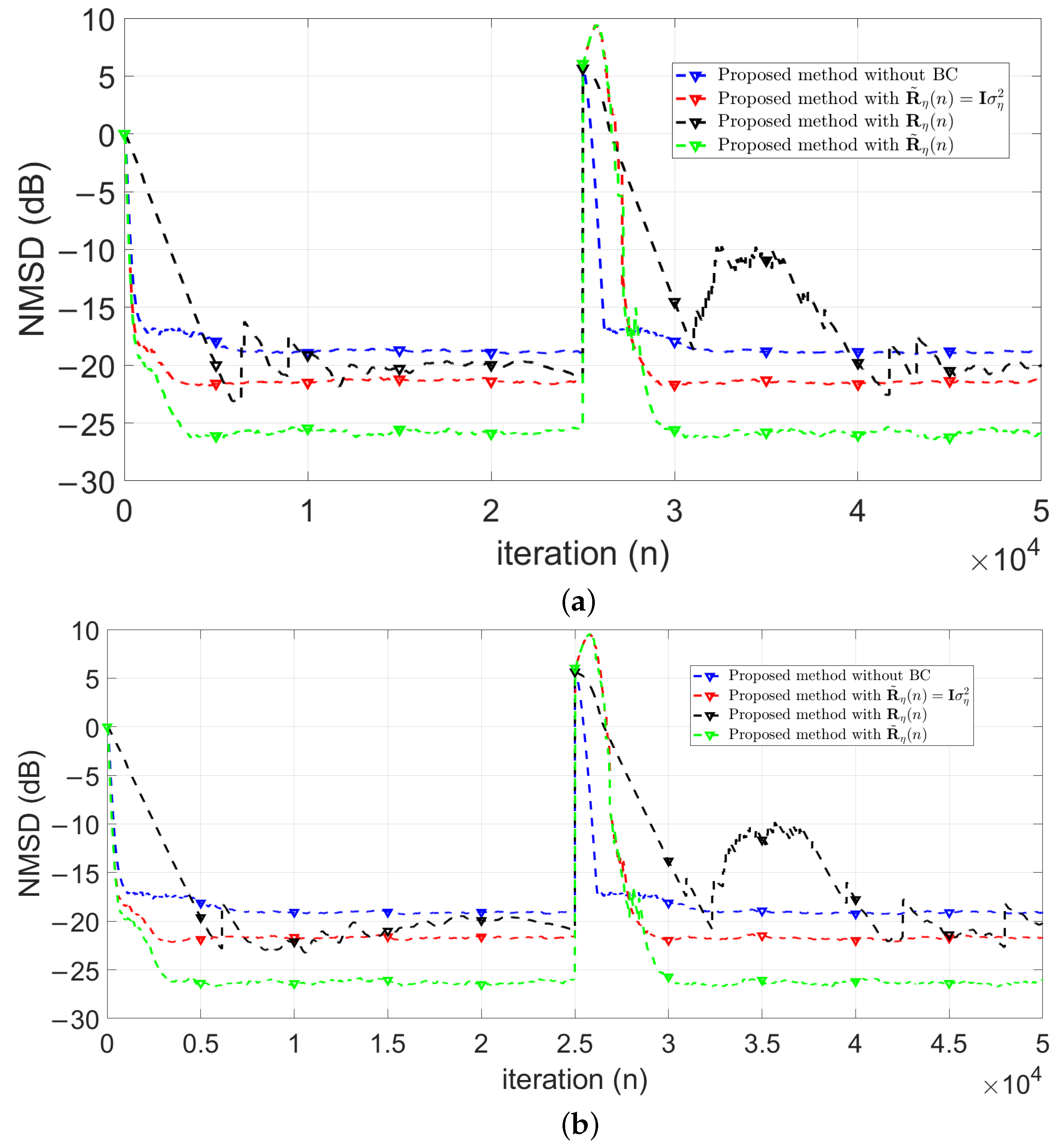

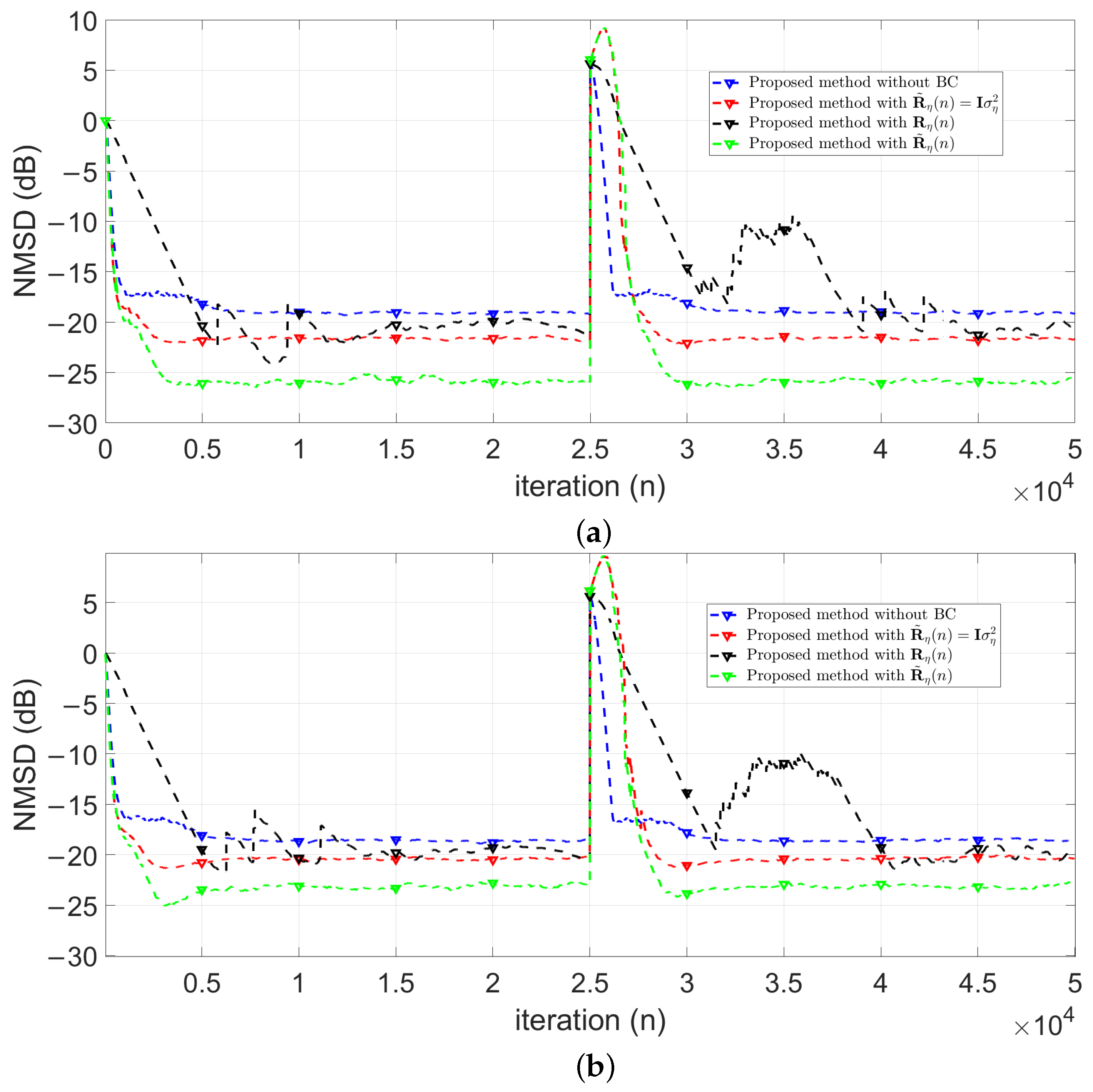

4.1. Evaluation of Robust Estimation of

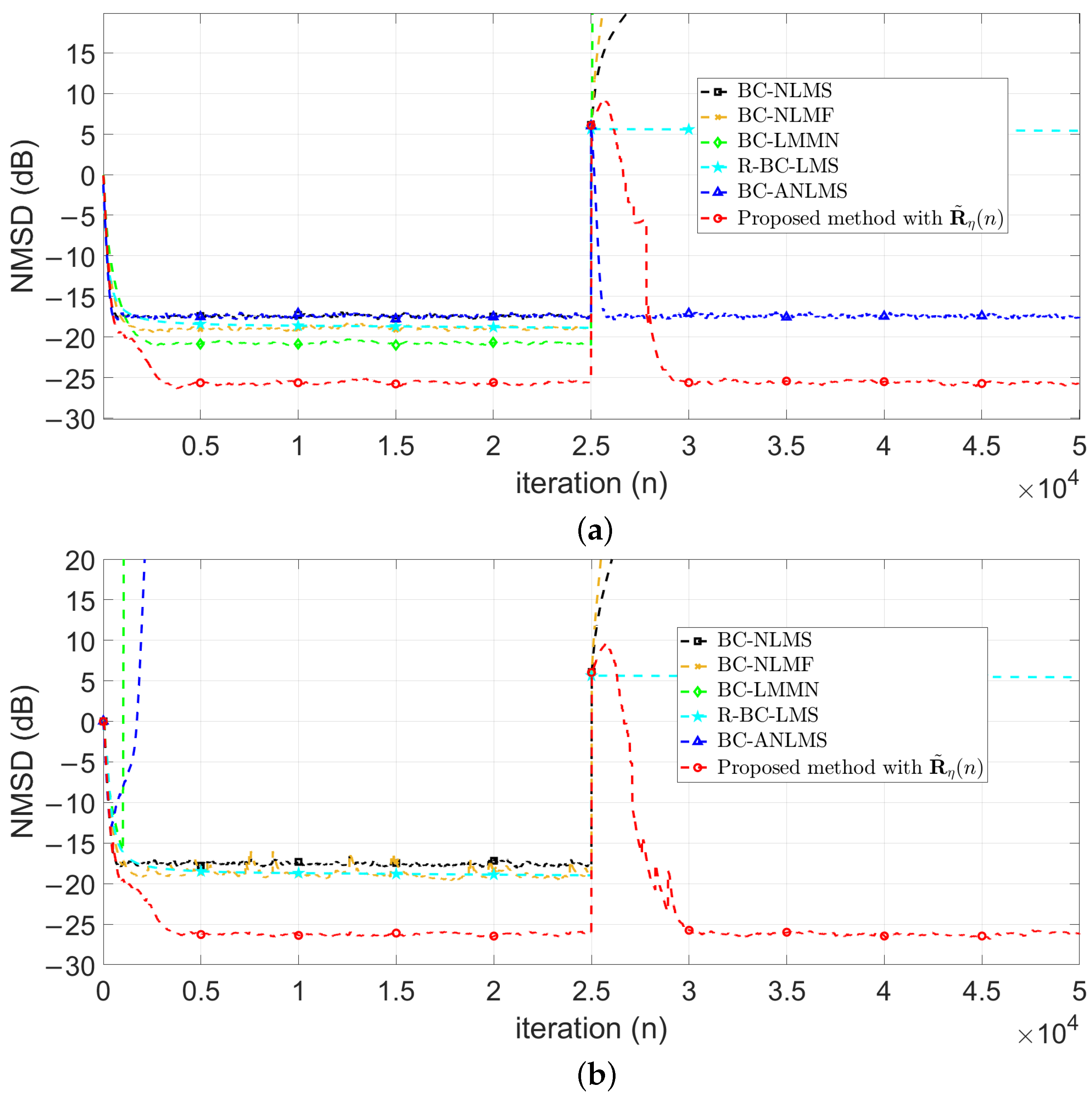

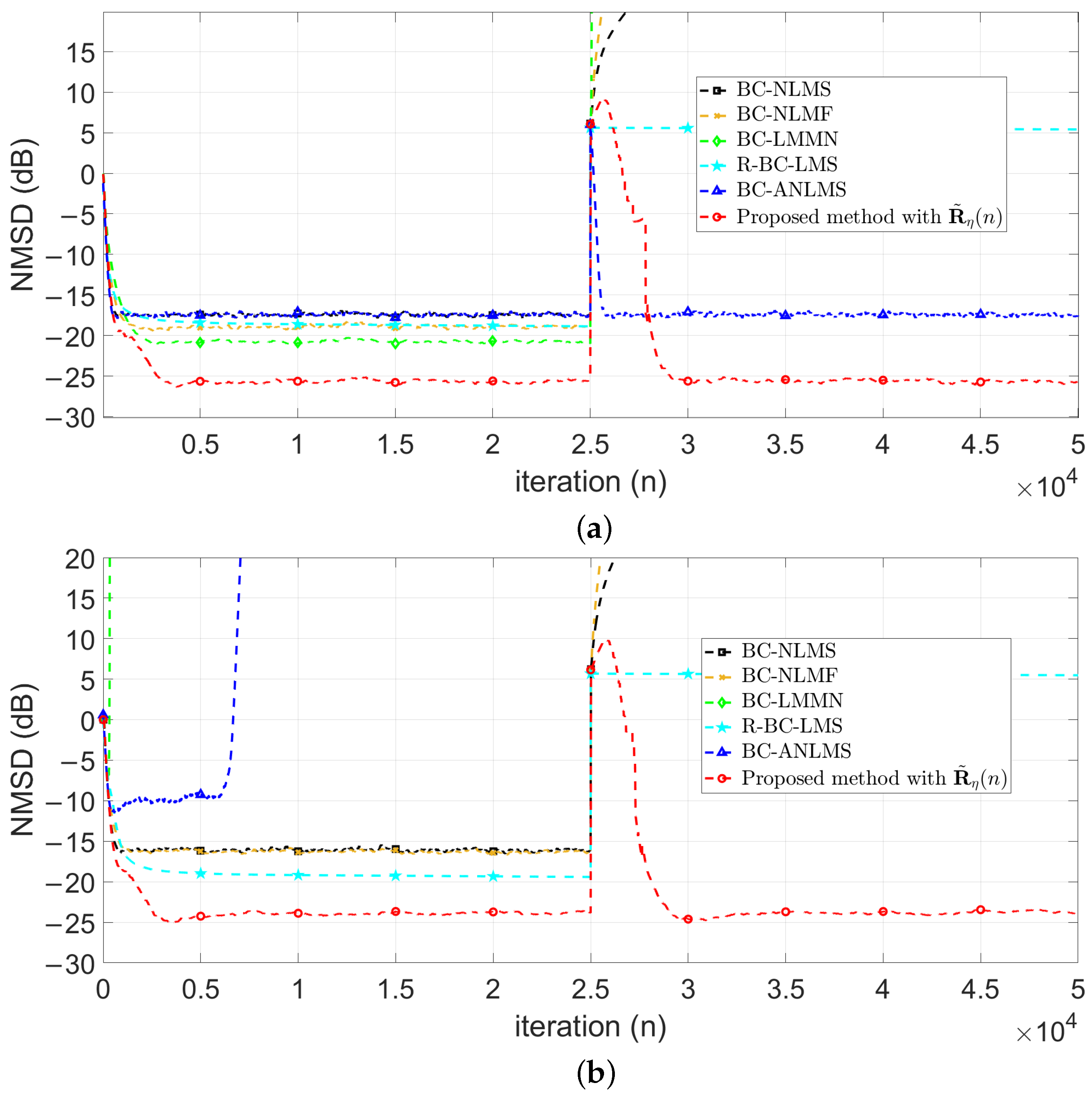

4.2. Comparisons with Related Works

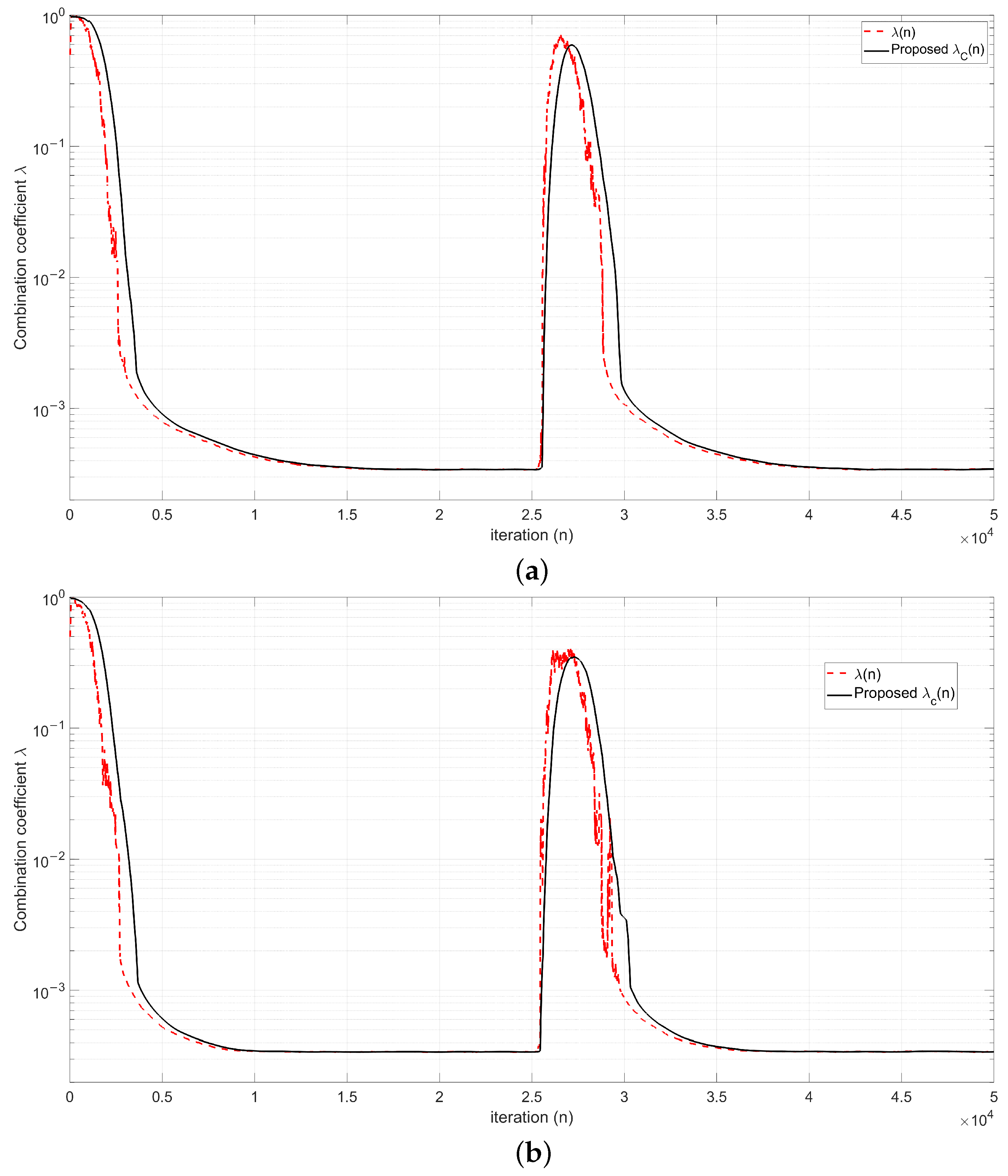

4.3. Evaluation of the Smoothed Convex-Combination

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AR(1) | First-Order Autoregressive Process |

| BC | Bias Compensation |

| BC-ANLMS | Bias-Compensated Arctangent NLMS |

| BC-LMMN | Bias-Compensated Least Mean Mixed-Norm |

| BC-NLMF | Bias-Compensated Normalized Least Mean Square |

| BCE-NLMS | Bias-Compensated Error-Modified NLMS |

| BG | Bernoulli-Gaussian |

| CC-BC-LMS | Convex Combination Bias-Compensated LMS |

| DOA | Direction of Arrival |

| EIV | Errors-In-Variable |

| FIR | Finite Impulse Response |

| LMS | Least Mean Square |

| MAP | Maximum A Posteriori |

| NLMS | Normalized Least Mean Square |

| NLMF | Normalized Least Mean Fourth |

| MMCC | Mixture Maximum Correntropy Criterion |

| NMSD | Normalized Mean Square Deviation |

| Probability Density Function | |

| R-BC-LMS | Robust Bias-Compensated LMS |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| -stable | Symmetric Alpha-Stable Distribution |

References

- Söderström, T. Errors-in-variables methods in system identification. Automatica 2007, 43, 939–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, L.; Wang, W.; Chen, B. Square Root Unscented Kalman Filter With Modified Measurement for Dynamic State Estimation of Power Systems. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas 2022, 71, 9002213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, L.; Yang, J.; Liu, M.; Chen, B. Differential Equation-Informed Neural Networks for State-of-Charge Estimation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas 2024, 73, 1000315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffrin, B. Total Least-Squares Collocation: An Optimal Estimation Technique for the EIV-Model with Prior Information. Mathematics 2020, 8, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, B. Multi-kernel correntropy based extended Kalman filtering for state-of-charge estimation. ISA Trans. 2022, 129, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Guo, T.N.; Chen, Z.; Fu, C. A Fast Multi-Source Sound DOA Estimator Considering Colored Noise in Circular Array. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 19, 6914–6926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, G.; D’Amato, R.; Ruggiero, A. Adaptive Rejection of a Sinusoidal Disturbance with Unknown Frequency in a Flexible Rotor with Lubricated Journal Bearings. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhao, H.; Liu, D.; Guo, X. Distributed Active Noise Control Robust to Impulsive Interference. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 11480–11490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ma, J.; Huang, Z.; Liu, K. Multitarget Vital Signs Estimation Based on Millimeter-Wave Radar in Complex Scenes. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 39432–39442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrhman, O.M.; Lv, S.; Li, S.; Dou, Y. Modified Sigmoid Function-Based Proportionate Diffusion Recursive Adaptive Filtering Algorithm Over Sensor Network. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 39478–39489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Zhao, H.; Long, X. Robust Linear-in-the-Parameters Nonlinear Graph Diffusion Adaptive Filter Over Sensor Network. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 16710–16720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Mohan Pradhan, P. Modeling Behavior of Sensors Using a Novel β-Divergence-Based Adaptive Filter. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 32641–32650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhao, H. Efficient DOA Estimation Method Using Bias-Compensated Adaptive Filtering. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 13087–13097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhao, H.; Xiang, W. Bias-compensated based diffusion affine projection like maximum correntropy algorithm. Digit. Signal Process. 2024, 154, 104702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eweda, E. Global Stabilization of the Least Mean Fourth Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2012, 60, 1473–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Park, T.; Park, P. Bias-Compensated Normalized Least Mean Fourth Algorithm for Adaptive Filtering of Impulsive Measurement Noises and Noisy Inputs. In Proceedings of the 2019 12th Asian Control Conference (ASCC), Kitakyushu, Japan, 9–12 June 2019; pp. 220–223. [Google Scholar]

- Chien, Y.R.; Hsieh, H.E.; Qian, G. Robust Bias Compensation Method for Sparse Normalized Quasi-Newton Least-Mean with Variable Mixing-Norm Adaptive Filtering. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Song, F.; Zhang, S.; So, H.C.; Yang, J. Robust Bias-Compensated LMS Algorithm: Design, Performance Analysis and Applications. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 13214–13228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.M.; Park, P. Normalised least-mean-square algorithm for adaptive filtering of impulsive measurement noises and noisy inputs. Electron. Lett. 2013, 49, 1270–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.; Shin, J.; Park, P. An Improved NLMS Algorithm in Sparse Systems Against Noisy Input Signals. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Ii Exp. Briefs 2015, 62, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Guo, L.; Li, Y. The Bias-Compensated Proportionate NLMS Algorithm With Sparse Penalty Constraint. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 4954–4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Yang, Z.; Li, Q.; Ma, L. Bias-Compensated PNLMS Algorithm With Multi-Segment Function for Noisy Input. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 43741–43748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, P.; Wang, B.; Qu, B.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, H.; Liang, J. Robust Bias-Compensated CR-NSAF Algorithm: Design and Performance Analysis. IEEE Trans. Syst., Man Cybern. Syst. 2025, 55, 674–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Zhao, H.; Hou, X. A Bias-Compensated NMMCC Algorithm Against Noisy Input and Non-Gaussian Interference. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Ii Exp. Briefs 2023, 70, 3689–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalin, P.A.; Nanda, S. A bias-compensated NLMS algorithm based on arctangent framework for system identification. Signal Image Video Process. 2024, 18, 3595–3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, H. LMS-based algorithm for unbiased FIR filtering with noisy measurements. Electron. Lett. 2001, 37, 1418–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zheng, Z. Bias-compensated affine-projection-like algorithms with noisy input. Electron. Lett. 2016, 52, 712–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chan, S.C.; Ho, K.L. New Sequential Partial-Update Least Mean M-Estimate Algorithms for Robust Adaptive System Identification in Impulsive Noise. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2011, 58, 4455–4470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas-Garcia, J.; Figueiras-Vidal, A.; Sayed, A. Mean-square performance of a convex combination of two adaptive filters. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2006, 54, 1078–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Zhao, H.; Li, K.; Chen, B. A Novel Normalized Sign Algorithm for System Identification Under Impulsive Noise Interference. Circuits Syst. Signal Process. 2015, 35, 3244–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas-Garcia, J.; Azpicueta-Ruiz, L.A.; Silva, M.T.; Nascimento, V.H.; Sayed, A.H. Combinations of Adaptive Filters: Performance and convergence properties. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2016, 33, 120–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Park, I.S.; Park, C.E.; Lee, H.; Park, P. Bias Compensated Least Mean Mixed-norm Adaptive Filtering Algorithm Robust to Impulsive Noises. In Proceedings of the 2020 20th International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems (ICCAS), Busan, Republic of Korea, 13–16 October 2020; pp. 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.R.; Efron, A. Adaptive robust impulse noise filtering. IEEE Transa. Signal Process. 1995, 43, 1855–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.; Nikias, C. Signal processing with fractional lower order moments: Stable processes and their applications. Proc. IEEE 1993, 81, 986–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thannoon, H.H.; Hashim, I.A. Hardware Implementation of a High-Speed Adaptive Filter Using a Combination of Systolic and Convex Architectures. Circuits Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 43, 1773–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, Y.R.; Wu, S.T.; Tsao, H.W.; Diniz, P.S.R. Correntropy-Based Data Selective Adaptive Filtering. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2024, 71, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, Y.R.; Chu, S.I. A Fast Converging Partial Update LMS Algorithm with Random Combining Strategy. Circuits Syst. Signal Process. 2014, 33, 1883–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Calculations | Adder | Multiplier |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | K | ||

| 2 | 1 | - | |

| 3 | in Equation (19) | ||

| 4 | in Equation (20) | - | |

| 5 | in Equation (18) | K | |

| 6 | in Equation (21) | ||

| Total |

| Algorithms | Adder | Multiplier |

|---|---|---|

| BC-NLMS [19] | ||

| BC-NLMF [16] | ||

| BC-LMMN [32] | ||

| R-BC-SA-LMS [18] | ||

| BC-ANLMS [25] | ||

| Proposed |

| Algorithms | Step Size |

|---|---|

| BC-NLMS [19] | |

| BC-NLMF [16] | |

| BC-LMMN [32] | |

| BC-ANLMS [25] | , |

| Proposed | , |

| Algorithms | Mild BG | Strong BG |

|---|---|---|

| BC-NLMS [19] | dB | dB |

| BC-NLMF [16] | dB | dB |

| BC-LMMN [32] | dB | (divergenced) |

| R-BC-SA-LMS [18] | dB | dB |

| BC-ANLMS [25] | dB | (divergenced) |

| Proposed method with | dB | dB |

| Algorithms | Mild Alpha Stable | Strong Alpha Stable |

|---|---|---|

| BC-NLMS [19] | dB | dB |

| BC-NLMF [16] | dB | dB |

| BC-LMMN [32] | dB | (divergenced) |

| R-BC-SA-LMS [18] | dB | dB |

| BC-ANLMS [25] | dB | (divergenced) |

| Proposed method with | dB | dB |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chien, Y.-R.; Hsieh, H.-E.; Qian, G. Robust Bias Compensation LMS Algorithms Under Colored Gaussian Input Noise and Impulse Observation Noise Environments. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3348. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13203348

Chien Y-R, Hsieh H-E, Qian G. Robust Bias Compensation LMS Algorithms Under Colored Gaussian Input Noise and Impulse Observation Noise Environments. Mathematics. 2025; 13(20):3348. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13203348

Chicago/Turabian StyleChien, Ying-Ren, Han-En Hsieh, and Guobing Qian. 2025. "Robust Bias Compensation LMS Algorithms Under Colored Gaussian Input Noise and Impulse Observation Noise Environments" Mathematics 13, no. 20: 3348. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13203348

APA StyleChien, Y.-R., Hsieh, H.-E., & Qian, G. (2025). Robust Bias Compensation LMS Algorithms Under Colored Gaussian Input Noise and Impulse Observation Noise Environments. Mathematics, 13(20), 3348. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13203348