A PDE Model of Glioblastoma Progression: The Role of Cell Crowding and Resource Competition in Proliferation and Diffusion †

Abstract

1. Introduction

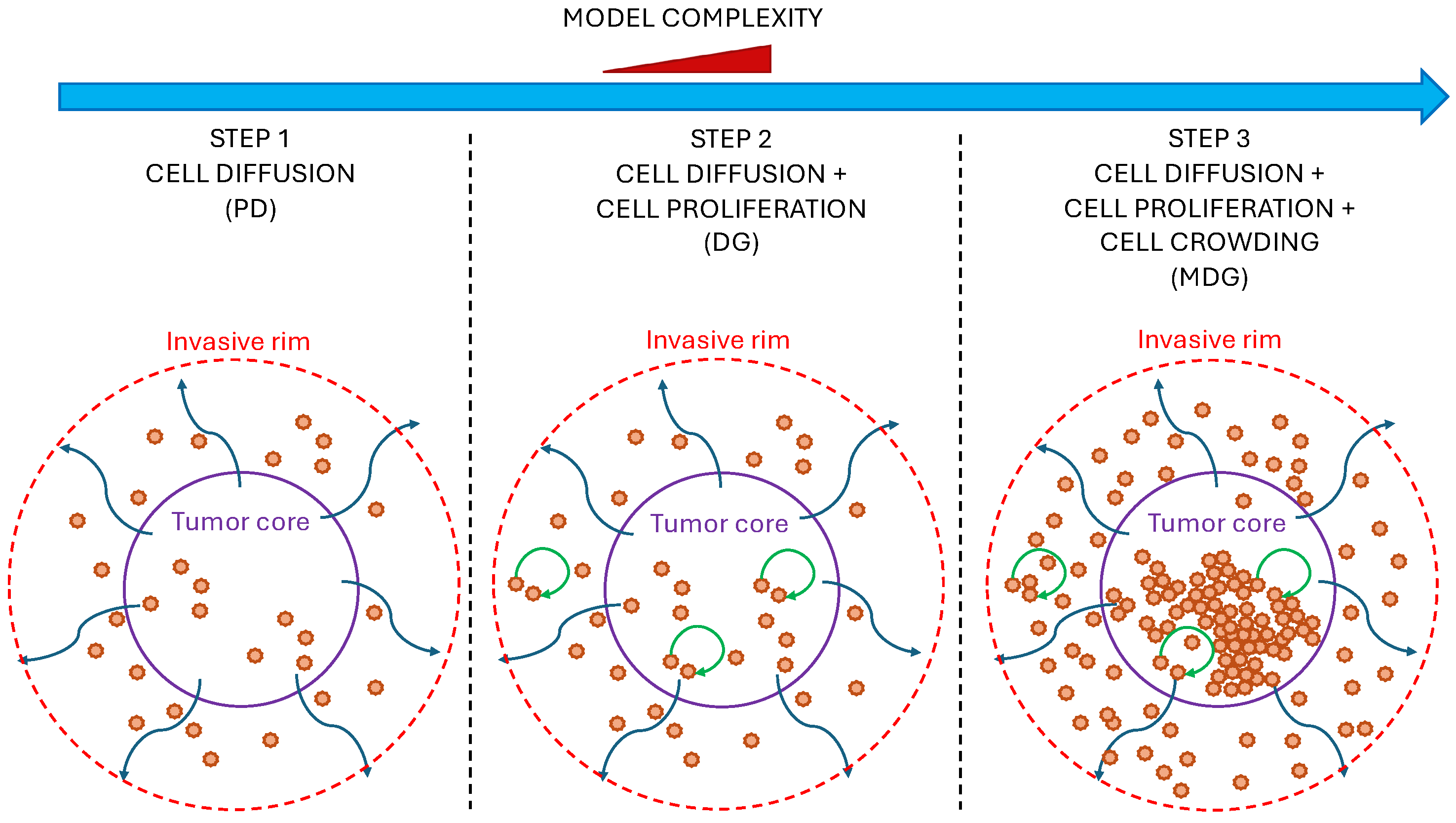

2. Mathematical Framework

2.1. Stochastic Differential Equations and the Fokker–Planck Equation

2.2. Fisher Equation

3. Glioblastoma Infiltration Modeling

- Polar coordinate formulation: Because of the assumption of symmetry and the isotropy of cell movements (already assumed in Pompa et al. [28]) within the tumor mass, we can reduce the spatial dependency to only the radial coordinate.

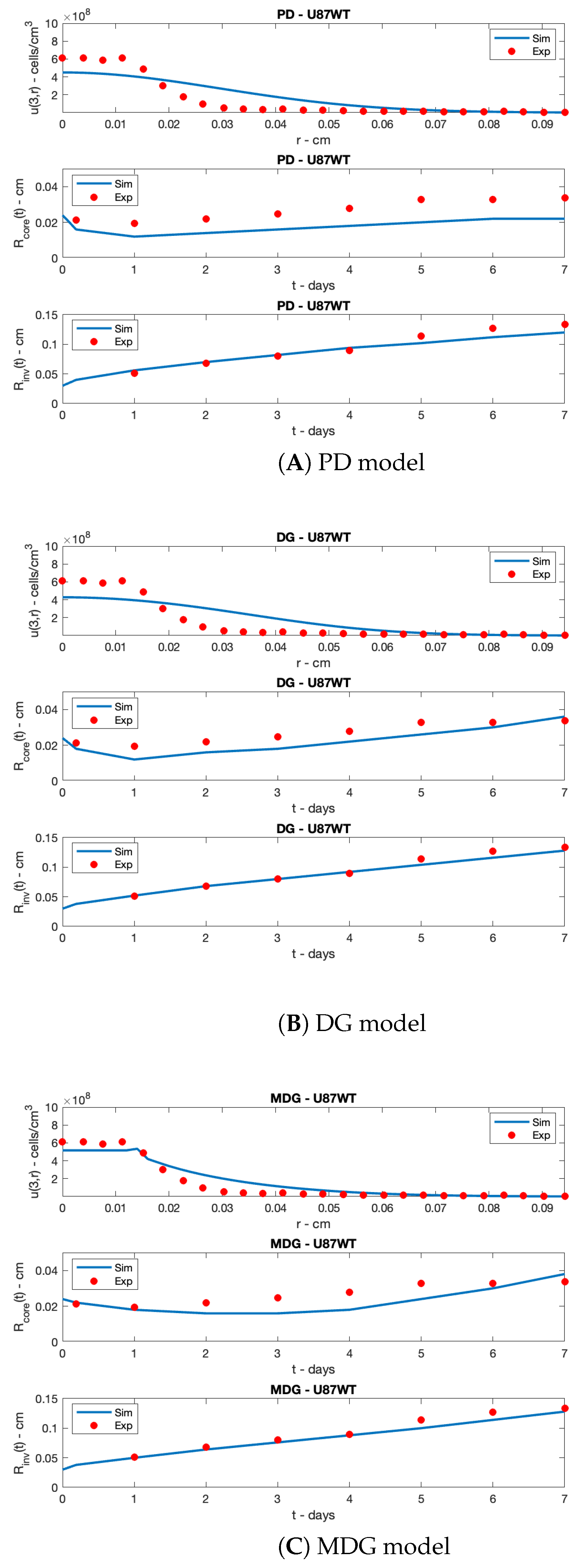

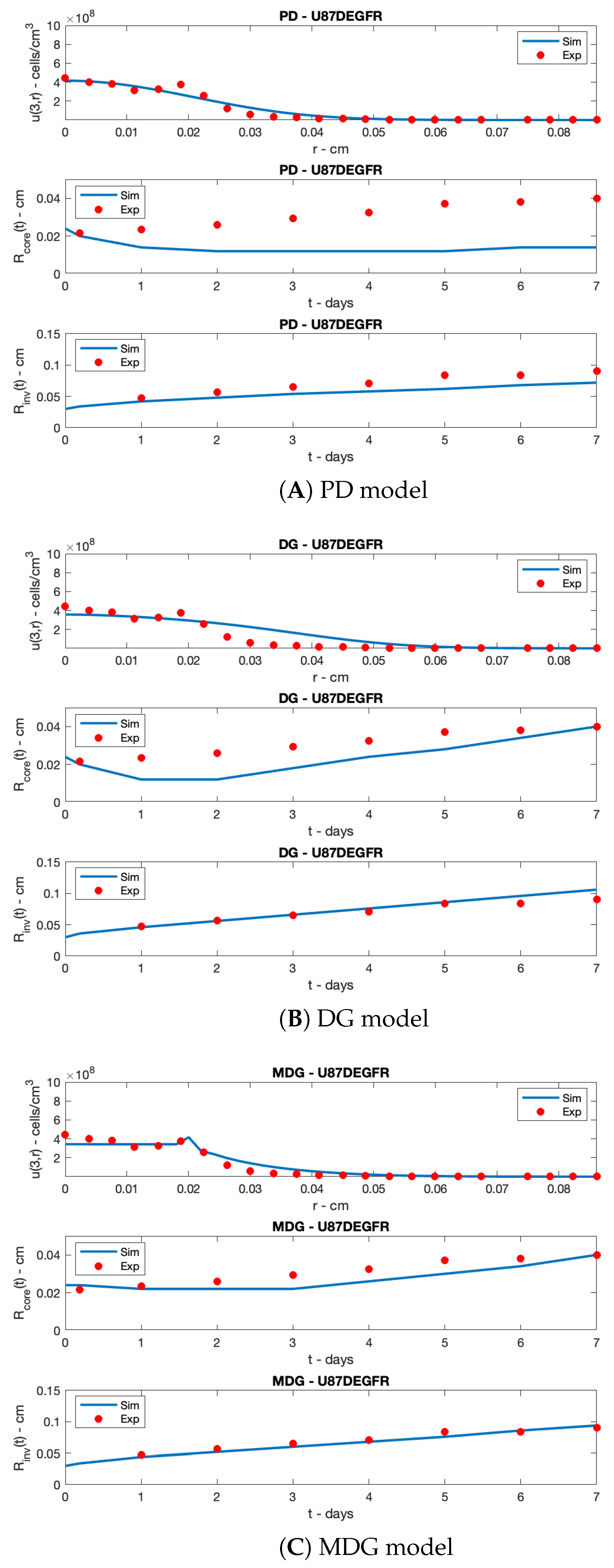

- Model outputs reproducing the available data on two different cell lines: U87WT (already considered in [28]) and U87EGFR, which is a common mutation (data reported in Stein et al. [20], see the next subsection); the proposed models are specified to the different cell lines by means of a suitable parameter estimation.

3.1. Data Collection

- The invasive radius, , of a tumor, which represents the maximum distance that a single tumor cell or a small group of tumor cells can migrate from the primary tumor mass into the surrounding tissue. The extension of the invasive region is a key parameter in cancer invasion studies, as it reflects the ability of malignant cells to infiltrate the extracellular matrix (ECM), evade immune responses, and establish metastases, thus increasing the probability of recurrences and a poor prognosis [34]. The image-based definition reported in Stein et al. [20] defines the invasive radius as the farthest distance from the center at which the modulus of the azimuthally averaged gradient of the gray intensity reaches half of its maximum value.

- The core radius, , which refers to the central region of the tumor where cell proliferation is significantly reduced or halted due to limited nutrient and oxygen availability. This region is often characterized by hypoxia, necrosis, or quiescence, depending on the severity of the nutrient and waste diffusion limitations. Again, according to the image-based definition reported in Stein et al. [20], the region is defined as the collection of pixels exhibiting an intensity level of on a grayscale—where 0 corresponds to the darkest pixel and 1 to the brightest—centered around the tumor spheroid.

- The radial cell density at day 3 (expressed in [cells/cm3]), a function of the radius , which is denoted by with ; it is extracted based on the concentration of darker pixels observed in the digital photomicrograph data.

3.2. Radial Distribution Models of Invasive Cells

3.2.1. Pure Diffusion Model (PD)

3.2.2. Diffusion and Growth Model (DG)

3.2.3. Modulated Diffusion and Growth Model (MDG)

4. Parameter Identification

- (i)

- , representing the radial distribution of cell density on days , measured at different spatial points with a sample size ;

- (ii)

- , representing the core radius at different times , with a sample size ;

- (iii)

- , representing the invasive radius at different times , with a sample size .

5. Simulation Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Louis, D.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.; Cree, I.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Hawkins, C.; Ng, H.K.; Pfister, S.; Reifenberger, G.; et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Neuro-Oncology 2021, 23, 1231–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, H.; Muzaffar, K.; Perveen, K.; Malhi, S.; Simjee, S. Glioblastoma Multiforme: A Review of its Epidemiology and Pathogenesis through Clinical Presentation and Treatment. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2017, 18, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, A.; Ashley, D.; Lopez, G.; Malinzak, M.; Friedman, H.; Khasraw, M. Management of glioblastoma: State of the art and future directions. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musielak, E.; Krajka-Kuzniak, V. Lipidic and Inorganic Nanoparticles for Targeted Glioblastoma Multiforme Therapy: Advances and Strategies. Micro 2025, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirsching, H.G.; Weller, M. Glioblastoma. Malig. Brain Tumors State Art Treat. 2017, 265–288. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, R.; He, H.; Wang, X. Novel neutrophil targeting platforms in treating Glioblastoma: Latest evidence and therapeutic approaches. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 150, 114173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rončević, A.; Nenad, K.; Anamarija, S.K.; Robert, R. Why Do Glioblastoma Treatments Fail? Future Pharmacol. 2025, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Luo, X.; Zhu, M.; Liu, N.; Li, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zou, C.; Wu, Y.; Cao, Z.; et al. Synergistic strategies for glioblastoma treatment: CRISPR-based multigene editing combined with immune checkpoint blockade. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyran, K.; Gozde, K.; Serkan, A.; Gokcen, C.; Ahmet, I.I.; Gozde, Y. Evaluating Immunotherapy Responses in Neuro-Oncology for Glioblastoma and Brain Metastases: A Brief Review Featuring Three Cases. Cancer Control 2025, 32, 10732748251322072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, G.A.; Adamson, D.C. Similarities in Mechanisms of Ovarian Cancer Metastasis and Brain Glioblastoma Multiforme Invasion Suggest Common Therapeutic Targets. Cells 2025, 14, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saketh, R.K.; Dunja, G.; Daniele, T.; Lucy, J.B.; Ting, G.; Andreas Christ Sølvsten, J.; Ciaran, S.H.; Melanie, C.; Tammy, L.K.; Jack, A.W.; et al. Detecting glioblastoma infiltration beyond conventional imaging tumour margins using MTE-NODDI. Imaging Neurosci. 2025, 3, imag_a_00472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, C.D.; Sofia, M.C.; Alexandra, M.; Filipa, E.; Ana Luísa, D.S.C.; Marco, A.C.; Mónica, T.F. Advancing Glioblastoma Research with Innovative Brain Organoid-Based Models. Cells 2025, 14, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odangowei Inetiminebi, O.; Timipa Richard, O.; Elekele Izibeya, A.; Racheal Bubaraye, E.; Marcella Tari, J.; Ebimobotei Mao, B. Chapter 1—Radiogenomics and genetic diversity of glioblastoma characterization. In Radiomics and Radiogenomics in Neuro-Oncology; Saxena, S., Suri, J.S., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025; pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ray Zirui, Z.; Ivan, E.; Michal, B.; Andy, Z.; Benedikt, W.; Bjoern, M.; John, S.L. Personalized predictions of Glioblastoma infiltration: Mathematical models, Physics-Informed Neural Networks and multimodal scans. Med. Image Anal. 2025, 101, 103423. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Jeon, H.; Othmer, H. The Role of the Tumor Microenvironment in Glioblastoma: A Mathematical Model. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 64, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kar, N.; Özalp, N. A fractional mathematical model approach on glioblastoma growth: Tumor visibility timing and patient survival. Math. Model. Numer. Simul. Appl. 2024, 4, 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marek, B.; Monika, J.P.; Mariusz, B.; Juan, B.B.; Urszula, F. Dual CAR-T cell therapy for glioblastoma: Strategies to cure tumour diseases based on a mathematical model. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 1637–1666. [Google Scholar]

- Cacace, F.; Conte, F.; d’Angelo, M.; Germani, A.; Palombo, G. Filtering linear systems with large time-varying measurement delays. Automatica 2022, 136, 110084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzikirou, H.; Deutsch, A.; Schaller, C.; Simon, M.; Swanson, K. Mathematical modelling of glioblastoma tumour development: A review. Math. Model. Methods Appl. Sci. 2005, 15, 1779–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, A.M.; Demuth, T.; Mobley, D.; Berens, M.; Sander, L.M. A mathematical model of glioblastoma tumor spheroid invasion in a three-dimensional in vitro experiment. Biophys. J. 2007, 92, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, M.; Surulescu, C. Mathematical modeling of glioma invasion: Acid-and vasculature mediated go-or-grow dichotomy and the influence of tissue anisotropy. Appl. Math. Comput. 2021, 407, 126305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falco, J.; Agosti, A.; Vetrano, I.G.; Bizzi, A.; Restelli, F.; Broggi, M.; Schiariti, M.; DiMeco, F.; Ferroli, P.; Ciarletta, P.; et al. In silico mathematical modelling for glioblastoma: A critical review and a patient-specific case. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engwer, C.; Knappitsch, M.; Surulescu, C. A multiscale model for glioma spread including cell-tissue interactions and proliferation. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2015, 13, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Li, J.; Surulescu, C. Multiscale modeling of glioma pseudopalisades: Contributions from the tumor microenvironment. J. Math. Biol. 2021, 82, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, A.C.S.; Hill, C.S.; Sturrock, M.; Tang, W.; Karamched, S.R.; Gorup, D.; Lythgoe, M.F.; Parrinello, S.; Marguerat, S.; Shahrezaei, V. Data-driven spatio-temporal modelling of glioblastoma. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2023, 10, 221444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borri, A.; d’Angelo, M.; Palumbo, P. Self-regulation in a stochastic model of chemical self-replication. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2023, 33, 4908–4922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandolfi, A.; Franciscis, S.; d’Onofrio, A.; Fasano, A.; Sinisgalli, C. Angiogenesis and vessel co-option in a mathematical model of diffusive tumor growth: The role of chemotaxis. J. Theor. Biol. 2021, 512, 110526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompa, M.; Panunzi, S.; Borri, A.; De Gaetano, A. An Agent-Based Model of Glioblastoma Infiltration. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 23rd International Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Informatics (CINTI), Budapest, Hungary, 20–22 November 2023; pp. 383–390. [Google Scholar]

- Borri, A.; d’Angelo, M.; D’Orsi, L.; Pompa, M.; Panunzi, S.; De Gaetano, A. Stochastic modeling of glioblastoma spread: A numerical simulation study. In Proceedings of the 13th International Workshop on Innovative Simulation for Healthcare and 21st International Multidisciplinary Modeling & Simulation Multiconference (IWISH 2024), Tenerife, Spain, 18–20 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Risken, H. The Fokker-Planck Equation. In Springer Series in Synergetics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; Volume 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, R.; Kinderlehrer, D.; Otto, F. The variational formulation of the Fokker–Planck equation. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 1998, 29, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, A.; Petrovskii, I.; Piskunov, N. A Study of the Diffusion Equation with Increase in the Amount of Substance, and its Application to a Biological Problem. Mosc. Univ. Math. Bull. 1937, 1, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, K.R.; Bridge, C.; Murray, J.; Alvord, E.C., Jr. Virtual and real brain tumors: Using mathematical modeling to quantify glioma growth and invasion. J. Neurol. Sci. 2003, 216, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.J.; Diksin, M.; Chhaya, S.; Sairam, S.; Estevez-Cebrero, M.A.; Rahman, R. The Invasive Region of Glioblastoma Defined by 5ALA Guided Surgery Has an Altered Cancer Stem Cell Marker Profile Compared to Central Tumour. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, K.R.; Rockne, R.C.; Claridge, J.; Chaplain, M.A.; Alvord, E.C., Jr.; Anderson, A. Quantifying the role of angiogenesis in malignant progression of gliomas: In silico modeling integrates imaging and histology. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 7366–7375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skeel, R.D.; Berzins, M. A Method for the Spatial Discretization of Parabolic Equations in One Space Variable. SIAM J. Sci. Stat. Comput. 1990, 11, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagarias, J.C.; Reeds, J.A.; Wright, M.H.; Wright, P.E. Convergence Properties of the Nelder-Mead Simplex Method in Low Dimensions. SIAM J. Optim. 1998, 9, 112–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegedus, B.; Zàch, J.; Cziròk, A.; Lôvey, J.; Vicsek, T. Irradiation and Taxol treatment result in non-monotonous, dose-dependent changes in the motility of glioblastoma cells. J. Neurooncol. 2004, 67, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demuth, T.; Hopf, N.J.; Kempski, O.; Sauner, D.; Herr, M.; Giese, A.; Perneczky, A. Migratory activity of human glioma cell lines in vitro assessed by continuous single cell observation. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2000, 18, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glantz, S.A.; Slinker, B.K. Primer of Applied Regression and Analysis of Variance; McGraw-Hill, Health Professions Division: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1974, 19, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. In Selected Papers of Hirotugu Akaike; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 199–213. [Google Scholar]

| (A) U87WT cell line | ||||

| Parameter | m.u. | PD | DG | MDG |

| D | cm2 · h−1 | |||

| cells · cm−3 | ||||

| g | h−1 | - | ||

| cells · cm−3 | - | |||

| - | - | - | 0.6 | |

| - | - | - | 1.9 | |

| (B) U87EGFR cell line | ||||

| Parameter | m.u. | PD | DG | MDG |

| D | cm2 · h−1 | |||

| cells · cm−3 | ||||

| g | h−1 | - | ||

| cells · cm−3 | - | |||

| - | - | - | 0.4 | |

| - | - | - | 2.4 | |

| (A) U87WT cell line | |||

| Metrics | PD | DG | MDG |

| −163.39 | −168.25 | −192.18 | |

| (B) U87EGFR cell line | |||

| Metrics | PD | DG | MDG |

| −134.22 | −157.16 | −199.48 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

d’Angelo, M.; Papa, F.; D’Orsi, L.; Panunzi, S.; Pompa, M.; Palombo, G.; De Gaetano, A.; Borri, A. A PDE Model of Glioblastoma Progression: The Role of Cell Crowding and Resource Competition in Proliferation and Diffusion. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3318. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13203318

d’Angelo M, Papa F, D’Orsi L, Panunzi S, Pompa M, Palombo G, De Gaetano A, Borri A. A PDE Model of Glioblastoma Progression: The Role of Cell Crowding and Resource Competition in Proliferation and Diffusion. Mathematics. 2025; 13(20):3318. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13203318

Chicago/Turabian Styled’Angelo, Massimiliano, Federico Papa, Laura D’Orsi, Simona Panunzi, Marcello Pompa, Giovanni Palombo, Andrea De Gaetano, and Alessandro Borri. 2025. "A PDE Model of Glioblastoma Progression: The Role of Cell Crowding and Resource Competition in Proliferation and Diffusion" Mathematics 13, no. 20: 3318. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13203318

APA Styled’Angelo, M., Papa, F., D’Orsi, L., Panunzi, S., Pompa, M., Palombo, G., De Gaetano, A., & Borri, A. (2025). A PDE Model of Glioblastoma Progression: The Role of Cell Crowding and Resource Competition in Proliferation and Diffusion. Mathematics, 13(20), 3318. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13203318