A Lightweight Malware Detection Model Based on Knowledge Distillation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Methodology

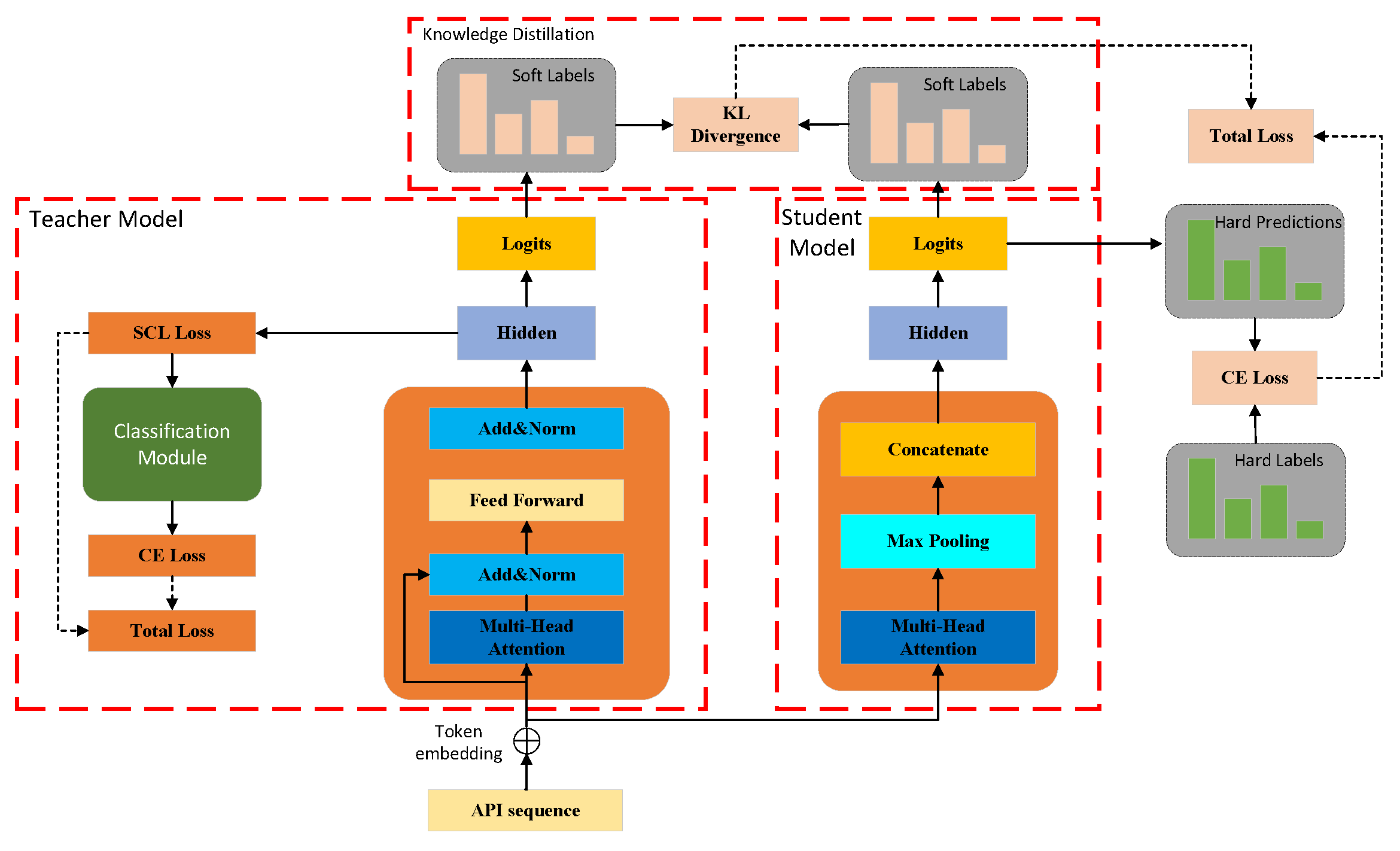

3.1. Framework

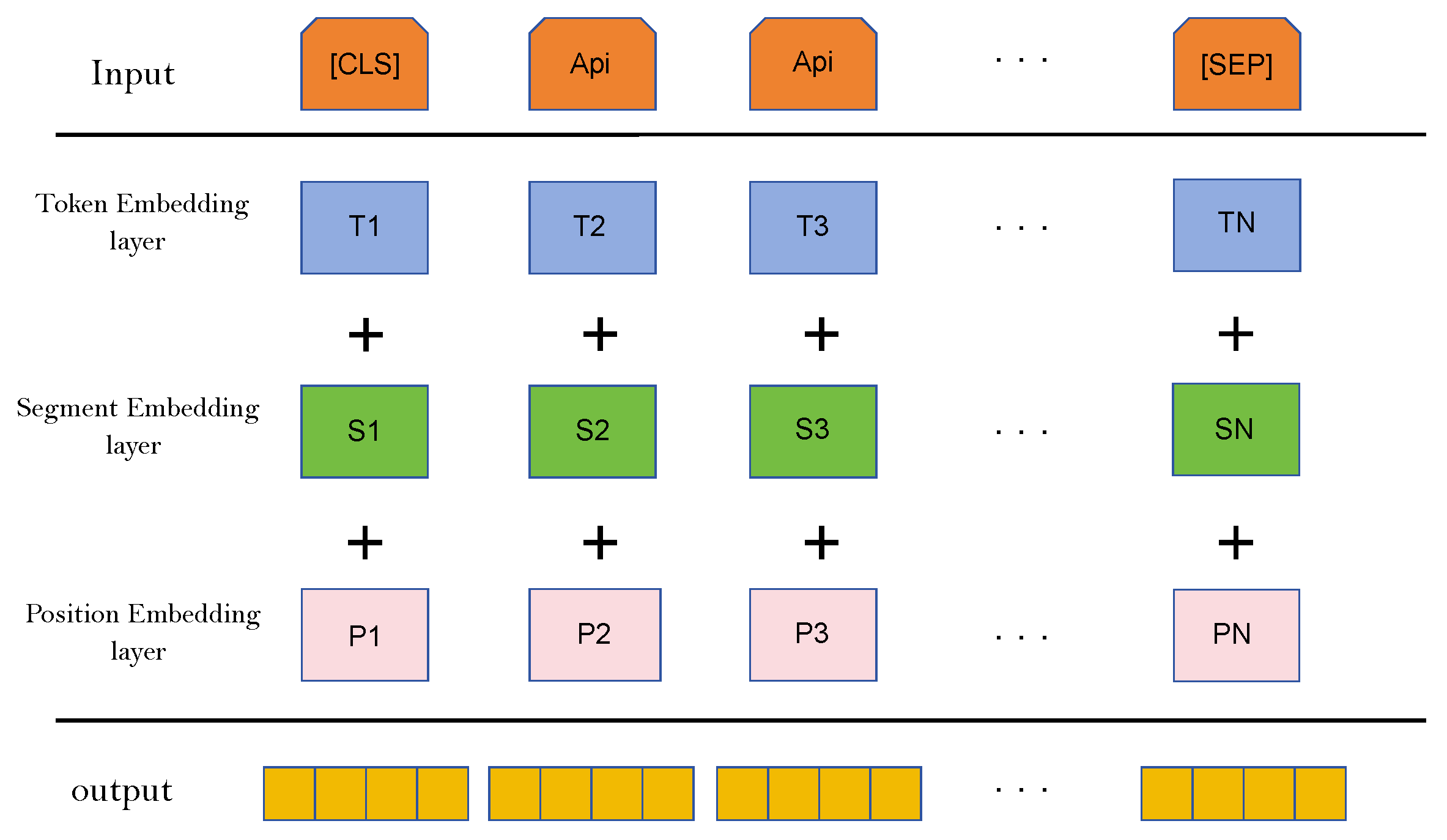

3.2. Data Pre-Processing and Embedding

3.3. The Pre-Trained Model Fine-Tuning

| Algorithm 1 The pre-trained model fine-tuning process |

|

3.4. Knowledge Distillation

4. Experiment

4.1. Experimental Setting

4.2. Dataset and Baseline

4.3. Results and Analysis

4.4. The Ablation Study

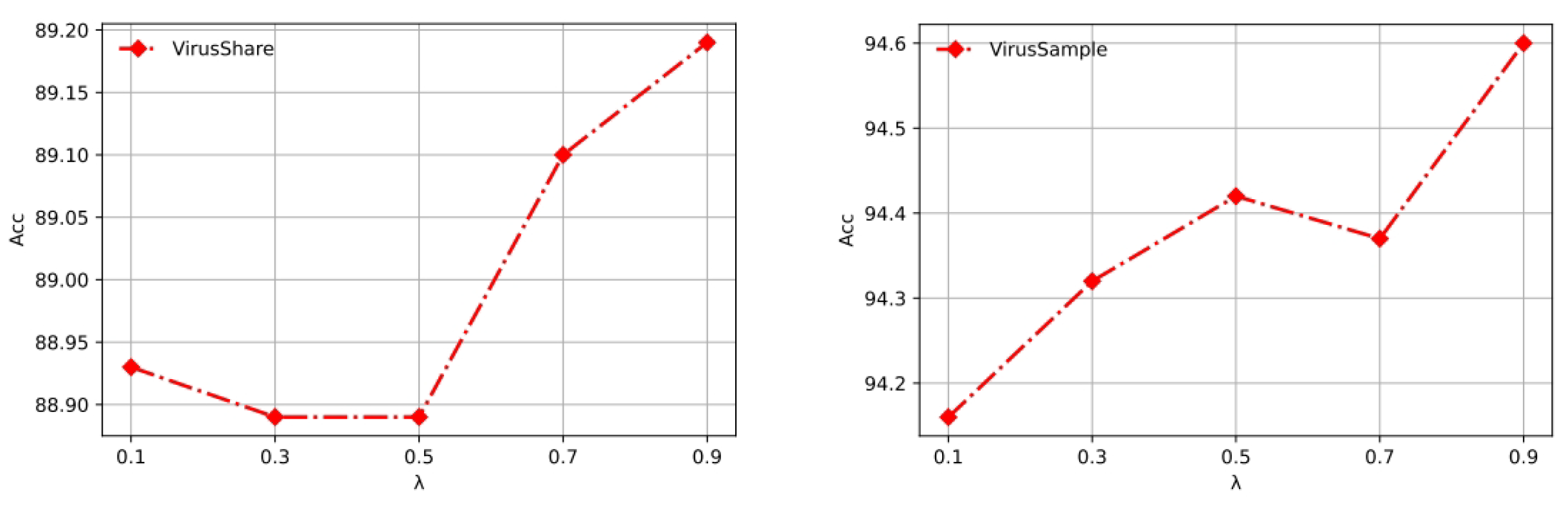

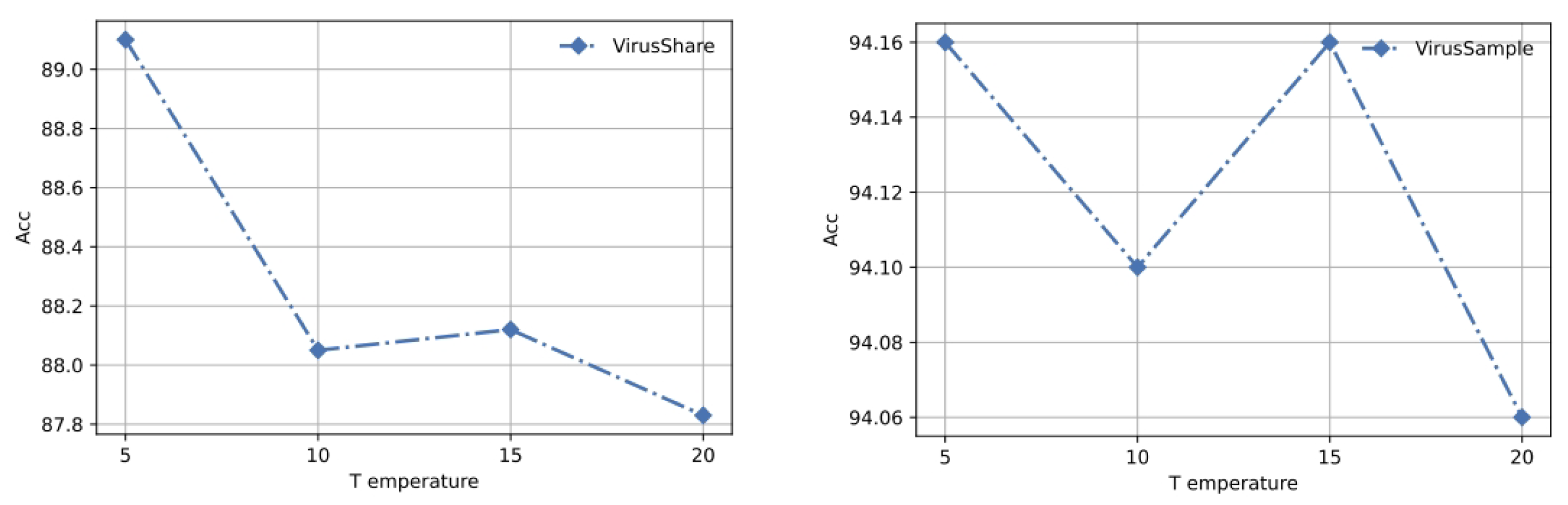

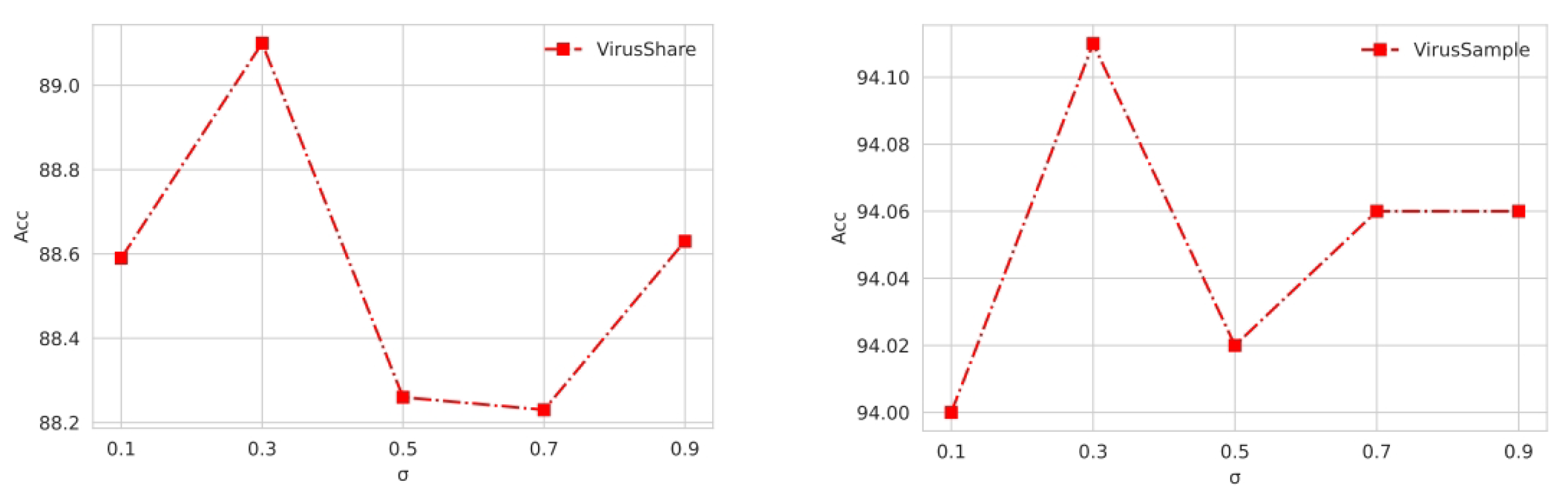

4.5. Parameter Sensitivity

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gopinath, M.; Sethuraman, S.C. A comprehensive survey on deep learning based malware detection techniques. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2023, 47, 100529. [Google Scholar]

- Raff, E.; Barker, J.; Sylvester, J.; Br, R.; Catanzaro, B.; Nicholas, C.K. Malware detection by eating a whole exe. In Proceedings of the Workshops at the Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Arp, D.; Spreitzenbarth, M.; Hubner, M.; Gascon, H.; Rieck, K. Drebin: Effective and explainable detection of android malware in your pocket. In Proceedings of the NDSS, San Diego, CA, USA, 23–26 February 2014; Volume 14, pp. 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gaber, M.G.; Ahmed, M.; Janicke, H. Malware detection with artificial intelligence: A systematic literature review. Acm Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almakayeel, N. Deep learning-based improved transformer model on android malware detection and classification in internet of vehicles. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A. Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training; OpenAI: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Prima, B.; Bouhorma, M. Using transfer learning for malware classification. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, 44, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasan, D.; Alazab, M.; Wassan, S.; Safaei, B.; Zheng, Q. Image-Based malware classification using ensemble of CNN architectures (IMCEC). Comput. Secur. 2020, 92, 101748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cui, W.; Geng, S.; Bo, B.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, W. A malware detection method of code texture visualization based on an improved faster RCNN combining transfer learning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 166630–166641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, G. Distilling the Knowledge in a Neural Network. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1503.02531. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, M.; You, S.; Wang, F.; Qian, C.; Xu, C. Knowledge diffusion for distillation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, L.; Cen, X.; Lu, H.; Yin, G.; Yin, M. A hierarchical feature-logit-based knowledge distillation scheme for internal defect detection of magnetic tiles. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 61, 102526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Xu, Z.; Zhu, H. A Novel Knowledge Distillation Framework with Intermediate Loss for Android Malware Detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Asia-Pacific Conference on Computer Science and Data Engineering (CSDE), Gold Coast, Australia, 18–20 December 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Geng, Z.; Jiang, F.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Lin, Z. Residual relaxation for multi-view representation learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 12104–12115. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Lin, T.; Xu, Y.; Chen, K.; Zhang, R. Relational contrastive learning for scene text recognition. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 29 October–3 November 2023; pp. 5764–5775. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Gu, H.; Lu, T.; Zhang, P.; Gu, N. Cl4ctr: A contrastive learning framework for ctr prediction. In Proceedings of the Sixteenth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Singapore, 27 February–3 March 2023; pp. 805–813. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Roundy, K.; Gates, C.; Vorobeychik, Y. Large-scale identification of malicious singleton files. In Proceedings of the Seventh ACM on Conference on Data and Application Security and Privacy, Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 22–24 March 2017; pp. 227–238. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, M.; Ulyanov, D.; Semenov, S.; Trofimov, M.; Giacinto, G. Novel feature extraction, selection and fusion for effective malware family classification. In Proceedings of the Sixth ACM Conference on Data and Application Security and Privacy, New Orleans, LA, USA, 9–11 March 2016; pp. 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Raman, K. Selecting features to classify malware. InfoSec Southwest 2012, 2012, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Kuppusamy, K.S.; Aghila, G. A learning model to detect maliciousness of portable executable using integrated feature set. J. King Saud-Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2019, 31, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.; Kruegel, C.; Kirda, E. Limits of static analysis for malware detection. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Third Annual Computer Security Applications Conference (ACSAC 2007), Miami Beach, FL, USA, 10–14 December 2007; pp. 421–430. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, J.; Singh, J. Detection of malicious software by analyzing the behavioral artifacts using machine learning algorithms. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2020, 121, 106273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinayakumar, R.; Alazab, M.; Soman, K.P.; Poornachandran, P.; Al-Nemrat, A.; Venkatraman, S. Deep learning approach for intelligent intrusion detection system. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 41525–41550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, Y.; Kim, E.; Kim, H.K. A novel approach to detect malware based on API call sequence analysis. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2015, 11, 659101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Ma, L.; Yang, W.; Zhong, Y. A method for windows malware detection based on deep learning. J. Signal Process. Syst. 2021, 93, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catak, F.O.; Yazı, A.F.; Elezaj, O.; Ahmed, J. Deep learning based Sequential model for malware analysis using Windows exe API Calls. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2020, 6, E285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zheng, J. API call-based malware classification using recurrent neural networks. J. Cyber Secur. Mobil. 2021, 10, 617–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, F.; Hubballi, N. Malware detection and classification using transformer-based learning. Ph. D. Thesis, Discipline of Computer Science and Engineering, IIT Indore, Indore, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Fang, X.; Yang, G. Mal: A novel pre-training method for malware detection. Comput. Secur. 2021, 111, 102458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Saha, S. CyberBERT: BERT for cyberbullying identification. Multimed. Syst. 2022, 28, 1897–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; Omar, M. Detecting IoT Malware with Knowledge Distillation Technique. In Proceedings of the 2023 Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering, & Applied Computing (CSCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24–27 July 2023; pp. 131–135. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, T.; Yao, X.; Chen, D. Simcse: Simple contrastive learning of sentence embeddings. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.08821. [Google Scholar]

- Gunel, B.; Du, J.; Conneau, A.; Stoyanov, V. Supervised contrastive learning for pre-trained language model fine-tuning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.01403. [Google Scholar]

- Khosla, P.; Teterwak, P.; Wang, C.; Sarna, A.; Tian, Y.; Isola, P.; Maschinot, A.; Liu, C.; Krishnan, D. Supervised contrastive learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 18661–18673. [Google Scholar]

- Düzgün, B.; Cayır, A.; Demirkıran, F.; Kayha, C.N.; Gençaydın, B.; Dağ, H. New datasets for dynamic malware classification. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.15205. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, S.K.; Mitra, S. Multilayer Perceptron, Fuzzy Sets, Classifiaction; Indian Statistical Institute: Baranagar, India, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y. Convolutional neural networks for sentence classification. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1408.5882. [Google Scholar]

- Sanh, V.; Debut, L.; Chaumond, J.; Wolf, T. Distil, a distilled version of: Smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.01108. [Google Scholar]

| Malware Categories | Dataset | |

|---|---|---|

| VirusShare | VirusSample | |

| Trojan | 8919 | 6153 |

| Virus | 2490 | 2367 |

| Advertising Software | 908 | 222 |

| Back door | 510 | 447 |

| Download | 218 | N/A |

| Worm virus | 524 | 300 |

| Proxy | 165 | 165 |

| Ransomware | 115 | N/A |

| Total | 13,849 | 9372 |

| Metrics | Accuracy | M-Recall | M-Precision | M-F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLP | 0.917 | 0.435 | 0.576 | 0.469 |

| TextCNN | 0.931 | 0.707 | 0.633 | 0. 641 |

| Catak | 0.665 | 0.206 | 0.305 | 0.208 |

| BERT-base | 0.946 | 0.557 | 0.677 | 0.562 |

| DistillBert | 0.946 | 0.569 | 0.687 | 0.598 |

| DistillMal (Our’s) | 0.942 | 0.501 | 0.734 | 0.601 |

| Metrics | Accuracy | M-Recall | M-Precision | M-F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLP | 0.835 | 0.479 | 0.576 | 0.511 |

| TextCNN | 0.884 | 0.627 | 0.633 | 0. 678 |

| Catak | 0.663 | 0.283 | 0.374 | 0.303 |

| BERT-base | 0.892 | 0.652 | 0.878 | 0.701 |

| DistillBert | 0.890 | 0.651 | 0.876 | 0.698 |

| DistillMal (Our’s) | 0.891 | 0.636 | 0.887 | 0.692 |

| Metrics | Parameters | Size | Avg Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| MLP | 133,384 | 0.127 MB | 0.576 |

| TextCNN | 1,970,888 | 1.880 MB | 0.114 |

| BERT-base | 109,880,072 | 110 MB | 9.013 |

| DistillBert | 66,760,712 | 63 MB | 4.598 |

| DistillMal (Our’s) | 1,970,888 | 1.880 MB | 0.189 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miao, C.; Kou, L.; Zhang, J.; Dong, G. A Lightweight Malware Detection Model Based on Knowledge Distillation. Mathematics 2024, 12, 4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/math12244009

Miao C, Kou L, Zhang J, Dong G. A Lightweight Malware Detection Model Based on Knowledge Distillation. Mathematics. 2024; 12(24):4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/math12244009

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiao, Chunyu, Liang Kou, Jilin Zhang, and Guozhong Dong. 2024. "A Lightweight Malware Detection Model Based on Knowledge Distillation" Mathematics 12, no. 24: 4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/math12244009

APA StyleMiao, C., Kou, L., Zhang, J., & Dong, G. (2024). A Lightweight Malware Detection Model Based on Knowledge Distillation. Mathematics, 12(24), 4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/math12244009