Abstract

In this paper, a Bayesian variable selection method for spatial autoregressive (SAR) quantile models is proposed on the basis of spike and slab prior for regression parameters. The SAR quantile models, which are more generalized than SAR models and quantile regression models, are specified by adopting the asymmetric Laplace distribution for the error term in the classical SAR models. The proposed approach could perform simultaneously robust parametric estimation and variable selection in the context of SAR quantile models. Bayesian statistical inferences are implemented by a detailed Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) procedure that combines Gibbs samplers with a probability integral transformation (PIT) algorithm. In the end, empirical numerical examples including several simulation studies and a Boston housing price data analysis are employed to demonstrate the newly developed methodologies.

Keywords:

Bayesian variable selection; quantile regression; spatial autoregressive models; Gibbs sampling; PIT algorithm MSC:

62F15

1. Introduction

Spatial regression models play a critical part in analyzing and tackling spatial data that is broadly available in spatial statistics, regional science, and spatial econometrics.In particularly, the spatial autoregressive (SAR) models proposed by Cliff and Ord [1] have received a lot of attention in recent years. For instance, LeSage and Pace [2] listed several Bayesian estimation and maximum likelihood estimation methods for SAR models in their monograph; based on a generalized method of moments estimator, Du et al. [3] made some statistical inferences for partially linear additive SAR models; under the condition of independent and identical distributed random errors terms in SAR models, Liu et al. [4] proposed a penalized quasi-maximum likelihood method which could perform parameter estimation and model selection simultaneously; Xie et al. [5] considered performing variable selection in SAR models with a diverging number of parameters; Jin and Lee [6] obtained a GEL estimation and investigated several typical test statistics of high-order SAR models; and recently, Ju et al. [7] developed Bayesian statistical diagnostics procedures in the framework of skew-normal SAR models. However, it is unfortunate that the methods proposed by all the cited works are based on the mean regression.

Quantile regression [8,9,10] studies the relationship among the quantile of the response with the explanatory variables, which provides a more robust and systematic path to investigate the dependence of the response on explanatory variables than mean regression. As a matter of fact, quantile regression considers how explanatory variables have impacts on the conditional quantiles of response variables instead of the conditional mean of the response variable, and presents a more comprehensive and complete picture of the relationship of the response variable with the explanatory variables. We refer the reader to Koenker [8] for an overview on quantile regression. It is noted that there has been a number of research papers on quantile regression issues in the Bayesian statistical framework. For example, Dunson and Taylor [11] presented a Bayesian method for quantile regression analysis based on the substitution likelihood idea [12]; Lancaster and Jun [13] conducted quantile regression analysis by utilizing Bayesian exponentially tilted empirical likelihood; Kottas and Krnjajic [14] developed a generalized Bayesian framework for quantile regression on the basis of Dirichlet processes; Yang and He [15] proposed a Bayesian quantile regression method which is equipped with empirical likelihood; and Rodrigues et al. [16] presented a Bayesian pyramid quantile regression approach that could make simultaneously statistical inferences at several different quantile levels. In particularly, it is a very natural, simple, and effective way to model Bayesian quantile regression by using asymmetric Laplace distribution, which has been studied by several authors, including Yu and Moyeed [17], Kozumi and Kobayashi [18], Hu et al. [19], and Wang and Tang [20], among others. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, little work has been carried out on Bayesian quantile analysis for SAR models due to their complex spatially dependent structure.Therefore, based on references [17,18] and spike and slab prior [21,22,23], which is often regarded as the gold standard in Bayesian variable selection setting, a Bayesian procedure is proposed to perform simultaneously parameter estimation and variable selection in SAR models. The novel contributions of this paper are listed as follows: (i) we consider a more generalized model than the SAR model and the quantile model, whose Bayesian analysis has not been done, and investigate the sensitivity of the Bayesian estimates to different prior inputs; (ii) we adopt asymmetric Laplace distribution for the error term [17,18] in the SAR models to build the hierarchical SAR quantile models and a full MCMC algorithm combining the Gibbs sampler and the probability integral transformation (PIT) algorithm is developed simultaneously to perform robust parametric estimation, to identify significant explanatory variables, and to build accurate predictive models in the considered models based on spike and slab prior [21,22,23]; (iii) the required conditional posterior distributions, which are more tedious than those in analysis of the SAR model and the quantile model, are derived, and the implementation of the PIT algorithm for generating observations from the tedious conditional posterior distribution is presented. (iv) Results obtained from empirical numerical examples show that the estimate performance, predictive performance, and variable selection performance of our proposed approach are indeed quite satisfactory.

This rest of the paper is arranged as follows. Hierarchical SAR quantile models using the asymmetric Laplace distribution for the error term [17,18] in the SAR models are proposed in Section 2. In Section 3, we explicitly describe a Bayesian variable selection procedure based on the spike and slab prior [21,22,23] in the SAR quantile model setting, which combines Gibbs sampling [24] with the probability integral transformation (PIT) algorithm [25] to perform parameter estimation and variable selection simultaneously. Several simulation studies are conducted and a real Boston housing price data anaysis is used to demonstrate our proposed methodologies in Section 4. A discussion is presented in the final section. Some sampling technique details are described within the appendix.

2. Hierarchical Bayesian Quantile Modeling for SAR Models

A Bayesian quantile regression approach for SAR models is proposed in this paper. At a given quantile level , a SAR quantile model has the following form,

for where is the observation on the response variables and denotes ; is spatial parameter; is the row and column element of an spatial weight matrix , whose diagonal elements are zeros and other elements are known constants; is a observation for explanatory variables of linear regressors ; the vector is the unknown regression coefficients; is a random error term with th quantile equaling 0, i.e., Quantile regression is often implemented by dealing with a minimization problem based on the check function. Under Equation (1), the specification problem evolves to estimate and by minimizing the following equation

in which is the check function defined by and represents the common indicator function. In the Bayesian statistical framework, it is assumed that are independently and identically distributed random variables and follows an asymmetric Laplace distribution with probability density function

in which is the scale parameter. Then the conditional distribution of y is specified by

Therefore, minimizing the Equation (2) is equivalent to maximizing the Equation (3). Followed by the location–scale mixture expression of asymmetric Laplace distribution [14], Equation (1) could be rewritten as

in which denotes that follows an exponential distribution with parameter , whose probability density function is ; is the standard normal random variable, and are mutually independent; and , respectively. The models defined in Equation (4) are referred to as the SAR quantile models in the paper. For ease of notation, we will delete in the representation in the following.

3. A Bayesian Variable Selection Procedure for SAR Quantile Models

3.1. Prior Specifications

To perform Bayesian statistical inferences, it is necessary to specify the prior distributions. The spike and slab prior for following references [21,22,23] is chosen to implement parameter estimation and variable selection in the framework of SAR quantile models in this paper. Specifically,

in which is the indicator variable vector, , denotes a vector whose each element is 0, . Or equivalently, for ,

i.e.,

Similar to Kozumi and Kobayashi (2011), the inverse Gamma prior is specified for , that is

where denotes an inverse Gamma distribution with shape parameter and scale parameter , i.e.,

Suppose that the prior distribution for is as follows:

in which represents the uniform distribution on the interval .

The following prior distribution for is considered in this paper:

In other words, for , the prior distribution of involved in is assumed to be a Bernoulli distribution, that is

We set that represents uniform prior in all numerical examples. Some other prior specifications for could be found by Cripps et al. [26].

For , the prior distribution of involved in is taken to be a inverse Gamma distribution, which is given by

In the end, , in the above prior specifications are hyperparameters whose values are already given. If not specified, we choose , within all numerical examples, which may stand for a case with noninformative prior.

3.2. Gibbs Sampling and Probability Integral Transformation (PIT) Algorithm

Denoting , a sequence of random samples is generated from the joint posterior distribution via the Gibbs sampler algorithm [24], and then parameter estimation and variable selection are simultaneously implemented by the obtained sequence of random draws. In our proposed algorithm, samplers are drawn iteratively from the following conditional posterior distributions:

, , , ,

, . The corresponding conditional posterior distributions in performing Gibbs sampler algorithm are listed in the following.

(1) Sample from conditional distribution , , noting that according to Equations (4) and (6), we have

where , , and .

(2) Sample from conditional distribution , and it can be shown to be

in which and , .

(3) Sample from conditional distribution . Through a simple algebra calculation, we have

in which denotes a identity matrix, denotes the determinant of A, .

(4) Sample from conditional distribution , . Noting that

where , .

(5) Sample from conditional distribution , . It can be shown that

where , , , denotes the generalized inverse Gauss distribution with parameters and , and if and only if

(6) Sample from conditional distriution , . Noting that is a Bernoulli distribution with

in which with .

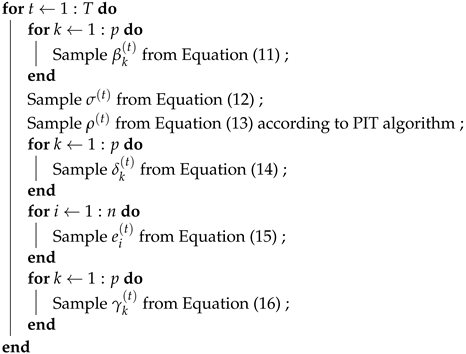

It is easily found that the conditional distributions (11), (12), (14). and (16) involved in the above Gibbs sampling method are lots of familiar distributions, such as the normal, inverse Gamma, and Bernoulli distribution, for example, whose sampling is fast and straightforward. In addition, there exist some efficient algorithms [27,28] to draw from the generalized inverse Gauss distribution (15). However, since conditional distribution (13) is nonstandard and unfamiliar distribution, it is rather difficult to draw directly observations for . Hence, the probability integral transformation (PIT) algorithm [25], which is a sampling procedure that we recommend to use in applications (e.g., in our simulation study and Boston data analysis of Section 4), is used to draw observations from it, and the sampling detail is described within the Appendix A. Finally, the MCMC algorithm is summarized in the following Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: An MCMC-based sampling algorithm for the SAR quantile models |

Input: setup initial values β(0), σ(0), ρ(0), e(0), δ(0), and γ(0), and the number of iterations of the sampling algorithm T.  Output: a sequence of samples {(β(t), σ(t), ρ(t), e(t), δ(t), γ(t)): t = 1, ⋯, T. |

3.3. Bayesian Estimates and Standard Errors

Observations simulated from the above proposed MCMC algorihtm (Algorithm 1) could be employed to calculate the joint Bayesian estimates, standard errors of unknown parameters , and latent variables . Let ,T} be observations simulated from the joint posterior distribution via the proposed method after the algorithm converges. The joints Bayesian estimates (consistent estimates) of are caculated by their posterior sample mean [29],

Similarly, the estimated standard errors of are obtained by their posterior sample standard errors.

4. Numerical Examples

In this section, several simulation studies and Boston housing price data analysis are employed to demonstrate the proposed Bayesian variable selection procedure.

4.1. Simulation Studies

The response is generated from the following model

with , where each p-dimensional is independently generated from the normal distribution , in which the element of is for and . The same as Chen et al. [30], we set and for other elements of the spatial matrix are all zero. For spatial parameter, , which stand for three spatial dependences of the responses, are considered in each simulation setting, respectively. represents negative and relatively strong spatial dependence, represents independence, whereas represents positive and relatively strong spatial dependence. Similar to Alhamzawi et al. [31], the true values of are taken into account in the following four scenarios:

Scenario 1: , which corresponds to the dense case;

Scenario 2: ,which could be regarded as the sparse case;

Scenario 3: , which could be viewed as the very sparse case;

Scenario 4: with , which may represent a moderate p case.

Within each scenario, we consider 4 different choices for the distribution of error term , such that the quantile is 0:

(a): The normal distribution (denoted as normal), with such that quantile of is 0;

(b): The Student’s t distribution (denoted as t), with such that quantile of is 0;

(c): The Laplace distribution (denoted as Laplace),with such that quantile of is 0;

(d): The mixture of normal distribution (denoted as mixed-normal), with such that quantile of is 0.

For each scenario of and each choice of the error distribution, each spatial parameter and with three different quantile levels , we run 500 replications. In each replication, 5000 samples are collected to calculate Bayesian estimates of unknown parameters after 5000 burn-ins. Table 1 reports the mean and the root mean square error (denoted as RMSE in parentheses) of the Bayesian estimates based on 500 replications for scenario 1 setting. From Table 1, it is easy to see that (1) all the Bayesian estimates perform reasonably well, and the performance under normal error distributions is better than the performance under t, Laplace and mixed-normal error distributions in term of RMSEs; (2) the means of Bayesian estimates are quite close to their true values, which suggests that our proposed Bayesian quantile approach is very effective under different error distributions, different quantile levels, and different spatial parameters . Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 summarize the numerical results for Bayesian parametric estimations and variable selection simultaneously, based on 500 replications for scenarios 2–4, one for each scenario setting. Denoting MSE , MPE , and TP as the true positive number, which means the number of correctly identified zero coefficients.FP denotes the false positive number, which means the number of incorrectly identified non-zero coefficients. In our Bayesian statistical framework, the coefficient is identified as zero if the credible interval of this parameter covers zero. Otherwise, it is identified as non-zero. Furthermore, FPR (false positive rate), TPR (true positive rate), and MCC (Matthews correlation coefficient) [32] are defined as follows: FPR , TPR , MCC , in which FN and TN are the number of incorrectly identified zero coefficients and the number of correctly identified non-zero coefficients, respectively. It is clear that MCC has a range from to −1 to 1 and models with MCC closer to 1 have higher selection accuracy. The reported TP values (denoted as TP), FP values (denoted as FP), FPR values (denoted as FPR), TPR values (denoted as FPR), and MCC values (denoted as MCC) in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 are averaged values over 500 replications. It is noted that the MSE is an estimation performance index, the MPE is a prediction performance index, and TP, FP, FPR, TPR and MCC are variable selection performance indexes. Examinations of Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 indicate that (i) Most MSEs are not more than 0.02, which illustrates that the Bayesian estimation is robust and accurate; (ii) The vast majority of MPEs are not more than 0.25 and each MPE is smaller than 0.4, which demonstrates the predictive effect of our proposed approach is very good; (iii) Each TP is close to the number of true zero coefficients, each FP and FPR is close to 0, each TPR is close to 1. In particular, each MCC is bigger than 0.93 and most of them are clearly close to 1. All TPs, FPs, FPRs, TPRs and MCCs suggest that our proposed Bayesian variable selection procedure has extremely high selection accuracy. In short, the empirical performance (containing estimation performance, the predictive performance, and variable selection performance) of the Bayesian approach is quite satisfactory in our considered settings.

Table 1.

Means and RMSEs (in parentheses) in the first simulation study under Scenario 1.

Table 2.

Numerical results of the simulation study under Scenario 2.

Table 3.

Numerical results in the simulation study under Scenario 3.

Table 4.

Numerical results in the simulation study under Scenario 4.

4.2. Boston Housing Price Data Analysis

In this subsection, a real example relating to Boston housing price data, which was analyzed by Harrison and Rubinfeld [33], Du et al. [3], Liu et al. [4], Xie et al. [5] and many other authors, is adopted to illustrate the proposed Bayesian methodologies. The Boston housing price dataset contains 14 variables with 506 individuals, which cab be downloaded from the link: http://lib.stat.cmu.edu/datasets/boston (accessed on 18 July 2022); a detailed description of all the variables is summarized in Table 5. Our scientific interest is to investigate the relationship between the house price and the other variables in this study, while accounting for choosing several important variables to explain home price under the SAR quantile models. Based on the work of Harrison and Rubinfeld [33] and Liu et al. [4], log(MEDV) is treated as the response variable, and the other variables are taken as explanatory variables, where DIS, RAD, LSTAT are processed with the logarithm, and RM and NOX are processed with the square. For convenient analysis, all the variables are standardized in the paper such that their sample means become zero. Finally, all 14 variables are taken into account by the following SAR quantile model

where , , and , respectively. The response variable denotes MEDV and the other 13 explanatory variables are (CRIM), (ZN), (INDUS), (CHAS), (NOX), V (RM), (AGE), (DIS), (RAD), (TAX), (PTRATIO), (B), and (LSTAT), respectively. Moreover, similar to Ertur and KochGrowth [34], the initial spatial weight matrix is considered by the following

Table 5.

Description of the variables in Boston housing price data.

denotes the great-circle distance between the latitude and longitude coordinates of any two houses. Subsequently, for , we set and the initial weights are normalized such that . The prior distributions and hyperparameters are specified as presented in Section 3.

A total of 5000 posterior samplers after 5000 burn-ins are collected in the posterior analysis, Bayesian estimates (ESTs), standard error estimates (SEs). and credible intervals (CIs) of the unknown parameters under Gibbs sampling with the PIT algorithm and 3 different quantile levels ( ) are reported in Table 6. From these empirical results, it can be seen that the Bayesian variable selection method could simultaneously obtain robust parameter estimations and identify important explanatory variables under different quantile levels ( ). For example, under , , , , , and are identified to be important explanatory variables with a significantly negative effect on MEDV, and and are detected to be important explanatory variables with a significantly positive impact on MEDV, since their corresponding CIs do not cover zero; while , , , , , and appear to be insignificant at significance level 0.05 because their CIs cover zero.

Table 6.

Bayesian estimation results based on SAR quantile models in the Boston housing price data analysis.

Furthermore, we obtain parameter estimates based on a Bayesian estimation procedure for SAR models proposed by LeSage and Pace [2], and calculate the predictive root mean square error (PRMSE), which is defined as where is the mean of , and is the predicted value of in the jth iteration after 5000 burn-in iterations. The related computing results are reported in Table 7, and the PRMSE values corresponding to our proposed Bayesian method ( , which is the case with median regression) and the method proposed by LeSage and Pace are given by 0.4204 and 0.5136, respectively. Comparing these results with Table 3, we may find that: (1) the regression parameter and spatial parameter vary with different quantile levels (e.g., and ) in SAR quantile models, which implies the way that the covariates affect the MEDV (response variable) is different at different levels of the distribution of the MEDV, the same as to the spatial relationship (the latitude and longitude coordinates) of any two houses. In a word, compared with the Bayesian estimation procedure for SAR models proposed by LeSage and Pace (in general, ordinal mean regression methods), our proposed SAR quantile models and methodologies could provide a more comprehensive and complete description of the Boston housing price data structure; (2) in terms of estimation and prediction performance based on the SAR model of LeSage and Pace and our proposed SAR quantile mothod ( ), our median regression performs better than LeSage and Pace’s mean regression, since our proposed method has smaller standard errors and smaller PRMSE than those obtained by the method proposed by LeSage and Pace.

Table 7.

Bayesian estimation results based on SAR models [2] in the Boston housing price data analysis.

5. Discussion

A Bayesian quantile regression method for spatial autoregressive (SAR) models is presented in this paper. Furthermore, an efficient MCMC algorithm is elaborately designed for posterior inferences. Note that our proposed approach could perform simultaneously to obtain robust parameter estimations, to identify significant explanatory variables, and to build accurate predictive models in the context of SAR quantile models, as shown by our empirical numerical studies. Therefore, we strongly recommend using our proposed Bayesian procedure in spatial data analysis.

In spite of the excellent performances of our proposed approach, it also suffers from some limitations in application: (1) the linear relationship of the response variable and explanatory variables in SAR quantile models might not hold; (2) the quantile curves related to different quantile levels are fitted separately in the current version, and they might cross (violating the definition of quantiles); (3) the stability of our proposed approach is not good enough when quantile levels are very close to 0 and 1 (e.g., ); (4) in high dimensional or ultrahigh dimensional spatial data analysis, the performances of parametric estimation and variable selection for our proposed method are rather poor. The main contribution of this paper is to adopt the spike and slab prior method and the Bayesian quantile technique [17,18] to SAR models, then similar ideas could be further extended to other spatial regression models in future works. Furthermore, it is a potential future project to consider more robust Bayesian quantile methods (e.g., Bayesian composite quantile regression), and more advanced Bayesian variable selection techniques for SAR models in high dimensional or ultrahigh dimensional settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.X.; methodology, Y.Z.; software, Y.Z. and D.X.; data curation, Y.Z. and D.X.; formal analysis, Y.Z. and D.X.; Writing—original draft, Y.Z. and D.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 11761016 and 12161014; by Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number LY23A010013; by the National Statistical Science Research Project of China, grant number 2021LY011; by the Project of High Level Creative Talents in Guizhou Province of China; and by Guiyang University Multidisciplinary Team Construction Projects in 2021, grant number 2021-xk04.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The research data is available on the website http://lib.stat.cmu.edu/datasets/boston (accessed on 18 July 2022).

Acknowledgments

Sincere thanks to everyone who suggested revisions and improved this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Sampling for the Parameter ρ

The MH algorithm, which is a popular sampling method, is adopted to draw observations from the conditional distribution (13). At the tth iteration with a current value , a new candidate is generated from the following equation:

where is a random sample from the standard normal distribution, and are mutually independent; and c is a tuning parameter. is accepted with probability

Similar to LeSage and Pace [2], c could be chosen such that the average acceptance rate is about [0.4, 0.6].

The probability integral transformation (PIT) algorithm [25], another alternative sampling approach, could be used to draw observations from the the conditional distribution (13) by the following:

Step (i): denote divide the interval into equally spaced points such that,

where Obtain by quadrature numerical integration, where is the posterior cumulative distribution function for .

Step (ii): generate , for if , then is a random observation of the conditional distribution (13); Denoted as the posterior probability density function for , i.e., . If , let be , then using the Taylor expansion

thus, we obtain

In the end, if , then is a random observation of ; otherwise, we set , which is regarded as a random observation of .

It is noted that d can be selected empirically, or be chosen as a large value in simulation studies and data analysis (e.g., in the paper).In addition, a simulation study (refer to Appendix B) is conducted to compute the Bayesian estimates of parameters based on the above proposed MH algorithm and PIT algorithm in our SAR quantile models and compare their performances.

Appendix B

To compare the empirical performance of our proposed sampling approach (denoted as Gibbs sampling with PIT algorithm) with the typical sampling approach (such as Gibbs sampling with MH algorithm), the following simulation study is considered. The dataset is generated from the model and parameter settings given in scenario 1 of the simulation study in Section 4.1. In each replication, 5000 samples are collected to calculate Bayesian estimates of unknown parameters after 5000 burn-ins by using Gibbs sampling with the MH algorithm. The related computing results based on 500 data sets are reported in Table A1; Table A1 only gives partial results to save space. From Table A1 and Table 1, we have the following findings: these two MCMC procedures (Gibbs sampling with PIT algorithm and Gibbs sampling with MH algorithm) are quite effective.In general, they obtain similar and accurate estimate results about unknown parameters and their differences are very minor. Comparing the computing time of these two MCMC approaches, it roughly takes 6.1 s in a Thinkpad X240 server to run a data set for Gibbs sampling with the PIT algorithm, and it takes about 29.2 s to run a replication for Gibbs sampling with the MH algorithm. Note that Gibbs sampling with the MH algorithm depends heavily on the accept probability and the proposal distribution. Therefore, we recommend to use Gibbs sampling with the PIT algorithm (i.e., our proposed sampling approach) in applications.

Table A1.

Means and RMSEs (in parentheses) in the simulation study of Appendix B.

Table A1.

Means and RMSEs (in parentheses) in the simulation study of Appendix B.

| Error Distribution | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (−0.8, 0.5) | normal | 0.8461 | 0.8414 | 0.8329 | 0.8493 | 0.8334 | 0.8478 | 0.8441 | 0.8418 | −0.7983 |

| (0.1643) | (0.1867) | (0.1942) | (0.1754) | (0.1909) | (0.1802) | (0.1910) | (0.1522) | (0.0173) | ||

| t | 0.7983 | 0.8286 | 0.8231 | 0.8084 | 0.8384 | 0.8201 | 0.8062 | 0.8201 | −0.7969 | |

| (0.3020) | (0.3432) | (0.3525) | (0.3701) | (0.3606) | (0.3670) | (0.3653) | (0.2924) | (0.0215) | ||

| Laplace | 0.8259 | 0.8284 | 0.8438 | 0.8406 | 0.8305 | 0.8189 | 0.8433 | 0.7973 | −0.7978 | |

| (0.2225) | (0.2890) | (0.2908) | (0.2665) | (0.2783) | (0.2830) | (0.2929) | (0.2421) | (0.0194) | ||

| mixed-normal | 0.8164 | 0.8340 | 0.8358 | 0.8457 | 0.8273 | 0.8205 | 0.8508 | 0.8194 | −0.7988 | |

| (0.2161) | (0.2635) | (0.2605) | (0.2803) | (0.2793) | (0.2821) | (0.2812) | (0.2326) | (0.0189) | ||

| (0.8, 0.5) | normal | 0.8473 | 0.8410 | 0.8428 | 0.8528 | 0.8438 | 0.8345 | 0.8480 | 0.8422 | 0.7985 |

| (0.1594) | (0.1864) | (0.1857) | (0.1907) | (0.1912) | (0.1840) | (0.1852) | (0.1571) | (0.0183) | ||

| t | 0.8308 | 0.8287 | 0.8052 | 0.8410 | 0.8205 | 0.8158 | 0.8530 | 0.7742 | 0.7983 | |

| (0.2829) | (0.3697) | (0.3524) | (0.3447) | (0.3771) | (0.3835) | (0.3882) | (0.3151) | (0.0197) | ||

| Laplace | 0.8058 | 0.8294 | 0.8394 | 0.8217 | 0.8238 | 0.8603 | 0.8088 | 0.8327 | 0.7978 | |

| (0.2467) | (0.3066) | (0.2945) | (0.3027) | (0.3032) | (0.2893) | (0.2944) | (0.2380) | (0.0192) | ||

| mixed-normal | 0.8375 | 0.8436 | 0.8334 | 0.8396 | 0.8366 | 0.8266 | 0.8529 | 0.8147 | 0.7964 | |

| (0.2164) | (0.2409) | (0.2514) | (0.2568) | (0.2649) | (0.2553) | (0.2451) | (0.2193) | (0.0191) |

Appendix C

In order to survey the sensitivity of the Bayesian estimates to different prior inputs, we conduct the following simulation study. The dataset is generated from the model and parameter settings given in Scenario 1 of the simulation study in Section 4.1; the following two different prior inputs are considered:

Type (i): , , other prior inputs are set to be the same as those given in Section 4.1, which is regarded as another noninformative prior case, different from Section 4.1;

Type (ii): , , other prior inputs are taken to be the same as those given in Section 4.1, which is based on the suggestion of Fong et al. [35].

The corresponding results on the basis of 500 datasets are reported in Table A2, Table A2 only gives partial results to save space. Table A2 and Table 1 imply that: (1) estimates with type (i) and type (ii) prior inputs are better than those obtained from prior inputs in Section 4.1, but their differences are minor; (2) all the “means” values based on the 3 different prior inputs are very close to the true values of unknown parameters, which illustrates that Bayesian estimates are very accurate and are not sensitive to the prior inputs in our considered cases.

Table A2.

Means and RMSs (in parentheses) in the simulation study in Appendix C.

Table A2.

Means and RMSs (in parentheses) in the simulation study in Appendix C.

| Type (i) Prior Inputs | ||||||||||

| Error distribution | ||||||||||

| (0.8, 0.5) | normal | 0.8359 | 0.8587 | 0.8395 | 0.8519 | 0.8385 | 0.8506 | 0.8432 | 0.8360 | 0.7975 |

| (0.1478) | (0.1581) | (0.1592) | (0.1686) | (0.1743) | (0.1654) | (0.1732) | (0.1514) | (0.0182) | ||

| t | 0.8451 | 0.8299 | 0.8312 | 0.8288 | 0.8464 | 0.8390 | 0.8531 | 0.8240 | 0.7969 | |

| (0.1987) | (0.2489) | (0.2349) | (0.2327) | (0.2233) | (0.2353) | (0.2344) | (0.2165) | (0.0212) | ||

| Laplace | 0.8521 | 0.8405 | 0.8281 | 0.8395 | 0.8535 | 0.8388 | 0.8277 | 0.8397 | 0.7967 | |

| (0.1663) | (0.2012) | (0.2200) | (0.2000) | (0.1976) | (0.1966) | (0.2037) | (0.1724) | (0.0175) | ||

| mixed-normal | 0.8383 | 0.8361 | 0.8466 | 0.8474 | 0.8480 | 0.8326 | 0.8465 | 0.8217 | 0.7971 | |

| (0.1649) | (0.1920) | (0.1856) | (0.2069) | (0.2046) | (0.1964) | (0.1860) | (0.1657) | (0.0198) | ||

| Type (ii) Prior Inputs | ||||||||||

| Error distribution | ||||||||||

| (0.8, 0.5) | normal | 0.8273 | 0.8367 | 0.8505 | 0.8374 | 0.8375 | 0.8427 | 0.8355 | 0.8312 | 0.8001 |

| (0.1419) | (0.1654) | (0.1671) | (0.1659) | (0.1606) | (0.1619) | (0.1600) | (0.1408) | (0.0165) | ||

| t | 0.8133 | 0.8311 | 0.8253 | 0.8490 | 0.8332 | 0.8284 | 0.8373 | 0.8245 | 0.7990 | |

| (0.1915) | (0.2125) | (0.2035) | (0.2081) | (0.1958) | (0.1865) | (0.1956) | (0.1791) | (0.0186) | ||

| Laplace | 0.8140 | 0.8415 | 0.8212 | 0.8329 | 0.8466 | 0.8236 | 0.8335 | 0.8209 | 0.7996 | |

| (0.1647) | (0.1757) | (0.1877) | (0.1862) | (0.1914) | (0.1949) | (0.1943) | (0.1526) | (0.0176) | ||

| mixed-normal | 0.8199 | 0.8407 | 0.8257 | 0.8506 | 0.8254 | 0.8426 | 0.8342 | 0.8195 | 0.7999 | |

| (0.1656) | (0.1772) | (0.1961) | (0.1858) | (0.1952) | (0.1864) | (0.1872) | (0.1702) | (0.0183) | ||

References

- Cliff, A.D.; Ord, J.K. Spatial Autocorrelation; Pion Ltd.: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- LeSage, J.; Pace, R.K. Introduction to Spatial Econometrics; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.; Sun, X.Q.; Cao, R.Y.; Zhang, Z.Z. Statistical inference for partially linear additive spatial autoregressive models. Spat. Stat. 2018, 25, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, J.B.; Cheng, S.L. A penalized quasi-maximum likelihood method for variable selection in the spatial autoregressive model. Spat. Stat. 2018, 25, 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.F.; Cao, R.Y.; Du, J. Variable selection for spatial autoregressive models with a diverging number of parameters. Stat. Pap. 2020, 61, 1125–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.; Lee, L. GEL estimation and tests of spatial autoregressive models. J. Econom. 2019, 208, 585–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Yang, Y.; Hu, M.; Dai, L.; Wu, L. Bayesian Influence Analysis of the Skew-Normal Spatial Autoregression Models. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenker, R. Quantile Regression; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.O.; Yang, Y. Semiparametric approach to a random effects quantile regression model. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2011, 106, 1405–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Zhu, Z.; Lian, H. High-dimensional quantile tensor regression. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2020, 21, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Dunson, D.B.; Taylor, J. Approximate Bayesian inference for quantiles. J. Nonparametric Stat. 2005, 17, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavine, M. On an approximate likelihood for quantiles. Biometrika 1995, 82, 220–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, T.; Jun, S.J. Bayesian quantile regression methods. J. Appl. Econom. 2010, 25, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottas, A.; Krnjaji, M. Bayesian Semiparametric Modelling in Quantile Regression. Scand. J. Stat. 2009, 36, 297–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; He, X. Bayesian empirical likelihood for quantile regression. Ann. Stat. 2012, 40, 1102–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, T.; Dortet-Bernadet, J.L.; Fan, Y. Pyramid quantile regression. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 2019, 28, 732–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Moyeed, R.A. Bayesian quantile regression. Stat. Probab. Lett. 2001, 54, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozumi, H.; Kobayashi, G. Gibbs sampling methods for Bayesian quantile regression. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2011, 81, 1565–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhao, K.; Lian, H. Bayesian quantile regression for partially linear additive models. Stat. Comput. 2015, 25, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Q.; Tang, N.S. Bayesian quantile regression with mixed discrete and nonignorable missing Covariates. Bayesian Anal. 2020, 15, 579–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, E.; McCulloch, R. Variable selection via Gibbs sampling. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1993, 88, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishwaran, H.; Rao, J.S. Spike and slab variable selection: Frequentist and Bayesian strategies. Ann. Stat. 2005, 33, 730–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotelis, A.; Smith, M. Bayesian identification, selection and estimation of semiparametric functions in high-dimensional additive models. J. Econom. 2008, 143, 291–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geman, S.; Geman, D. Stochastic relaxation, Gibbs distribution, and the Bayesian restoration of images. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1984, 6, 721–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wichitaksorn, N.; Tsurumi, H. Comparison of MCMC algorithms for the estimation of Tobit model with non-normal error: The case of asymmetric Laplace distribution. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2013, 67, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cripps, E.; Carter, C.; Kohn, R. Variable selection and covariance selection in multivariate regression models. Handb. Stat. 2005, 25, 519–552. [Google Scholar]

- Dagpunar, J. An easily implemented generalized inverse Gaussian generator. Commun. Stat.- Simul. Comput. 1989, 18, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jøgensen, B. Statistical Properties of the Generalized Inverse GAUSSIAN Distribution; Springer: New York, NY, USA; Berlin, Germany, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Geyer, C.J. Practical markov chain monte carlo. Stat. Sci. 1992, 7, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, R.; Huang, Y. Semiparametric Spatial Autoregressive Model: A Two-Step Bayesian Approach. Ann. Public Health Res. 2015, 2, 1012–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Alhamzawi, R.; Yu, K.; Benoit, D.F. Bayesian adaptive Lasso quantile regression. Stat. Model. 2012, 12, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, B. Comparison of the predicted and observed secondary structure of t4 phage lysozyme. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Protein Struct. 1975, 405, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.H.; Rubinfeld, D.L. Hedonic housing prices and the demand for clean air. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 1978, 5, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertur, C.; KochGrowth, W. Growth technological interdependence and spatial externalities: Theory and evidence. J. Appl. Econom. 2007, 22, 1033–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, Y.; Rue, H.; Wakefield, J. Bayesian influence for generalized linear mixed models. Biostatistics 2010, 11, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).