Allowance for School Graduate Practice Performance in Slovakia: Impact Evaluation of the Intervention

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Literature Review

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aim of the Study

2.2. Method of the Evaluation

- logit model for on all and from which we predict probabilities for the participation of individuals in the Graduate practice ;

- ordinary least squares regression model of on all and ; the predicted values from this model are ;

- second ordinary least squares regression model of on all and ; the regression coefficient of the variable in this third regression represents the estimate of the average treatment effect.

2.3. Data and Period of the Analysis

- wage—the average monthly wage of individuals (in EUR) over a 24-month impact period;

- employment—the period of registration of individuals in the SIA as a full-time employed person or self-employed person (in days).

3. Results

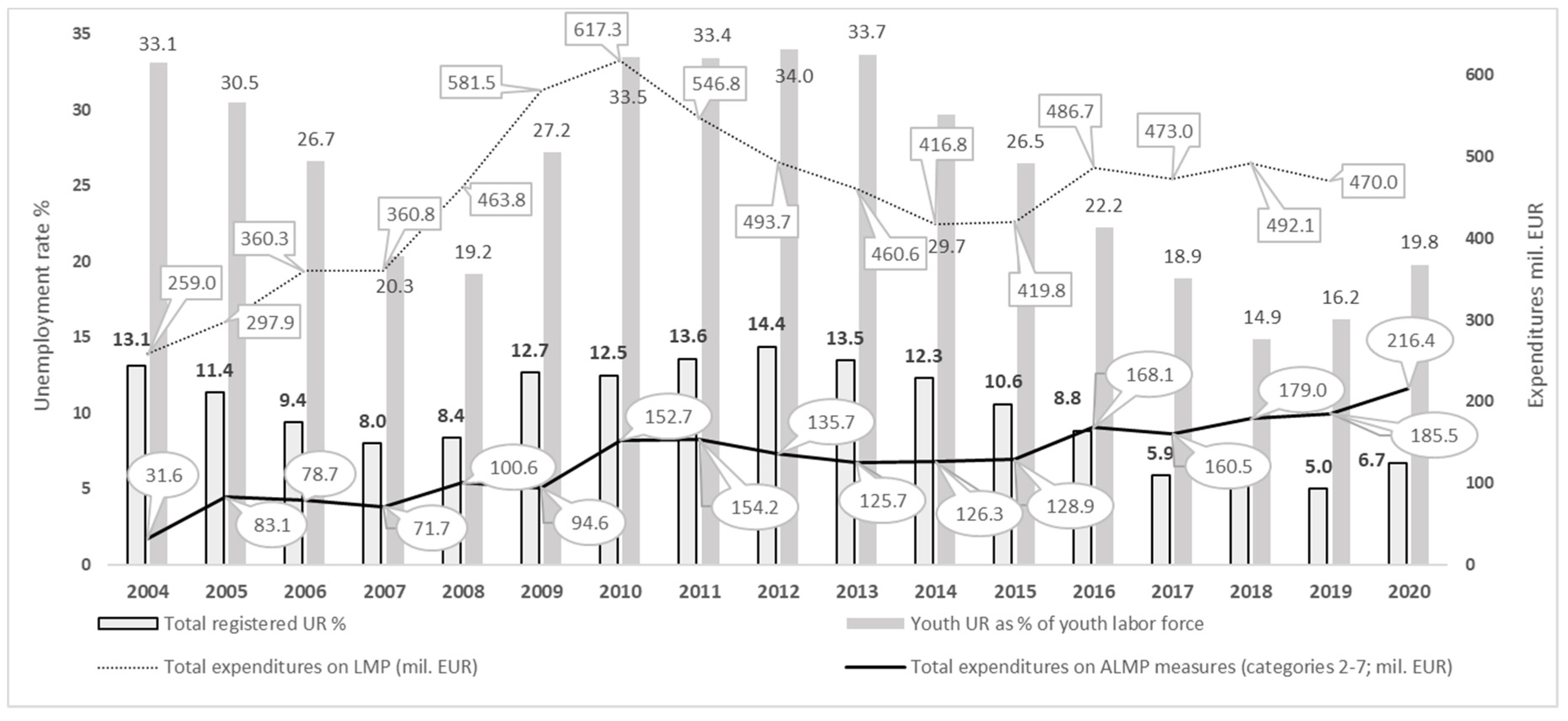

3.1. Basic Characteristics of the Labour Market and Labour Market Policy Measures in Slovakia

3.2. Legal Analysis of the Graduate Practice

- is a person not older than 26 years;

- has left the continuous preparation for a job with relevant education stage in the full-time study less than two years ago;

- at the same time, did not have a regular paid job for longer than six consecutive months before the official registration in the Register of jobseekers;

- is registered in the Register of jobseekers for at least one month.

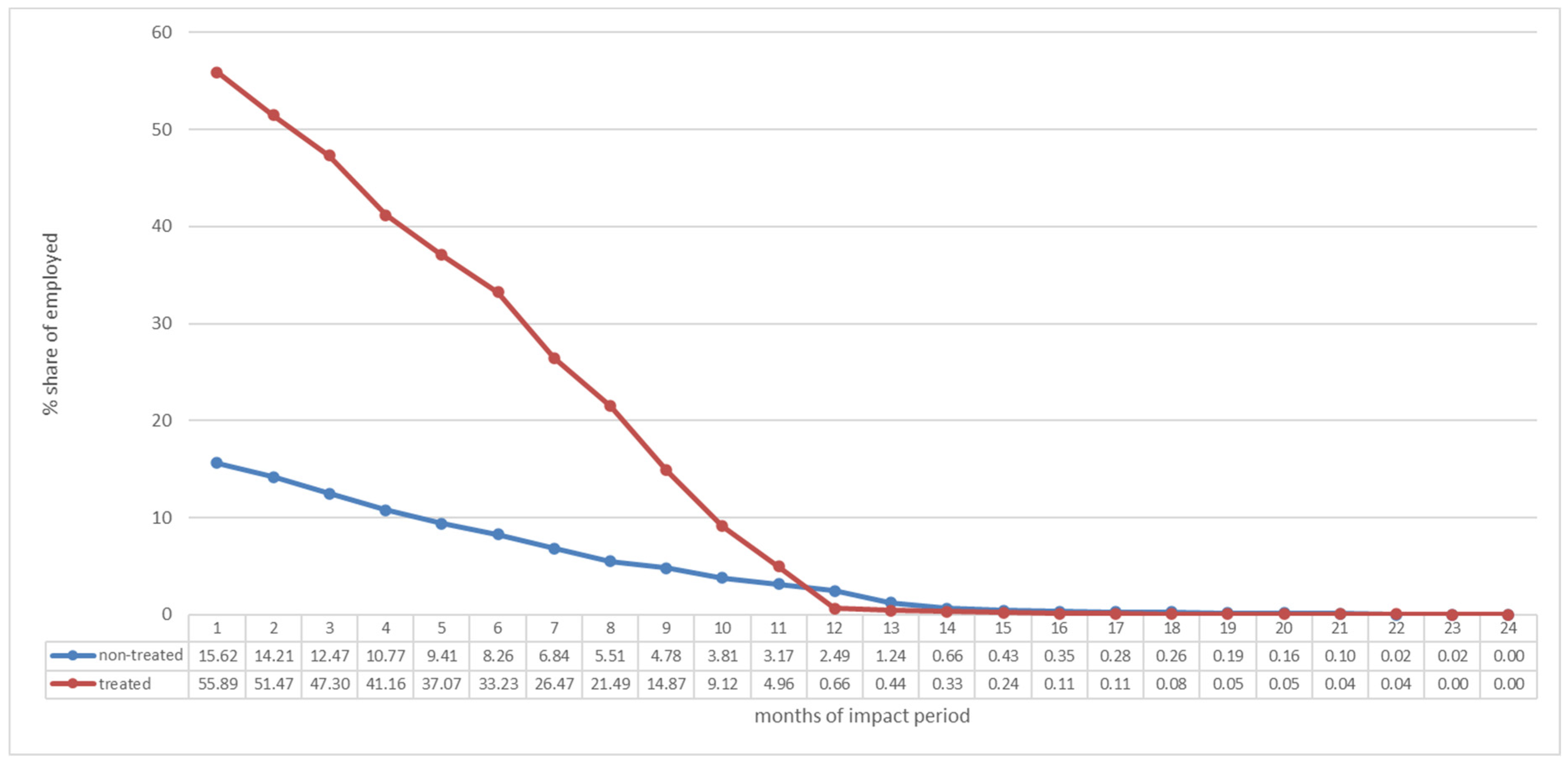

3.3. Results of the Counterfactual Evaluation of the Measure

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Total | Non-Treated | Treated |

|---|---|---|---|

| ageatregistration | 22.36 | 22.48 | 21.62 |

| previousevidence | 460.64 | 493.91 | 245.12 |

| evidencelength | 311.28 | 287.92 | 462.59 |

| ageshifted | 23.04 | 23.19 | 22.09 |

| Sharesin% | |||

| men | 0.55 | 0.59 | 0.35 |

| maritalstatus | |||

| married | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| divorced | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| NA | 0.61 | 0.70 | 0.00 |

| levelofeducation | |||

| primary | 8.48 | 9.70 | 0.60 |

| lowersecondary | 0.65 | 0.70 | 0.30 |

| secondaryvocational | 15.76 | 17.00 | 7.70 |

| completesecondaryvocational | 46.81 | 45.70 | 54.00 |

| uppersecondaryvocational | 7.13 | 6.70 | 9.90 |

| highervocational | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| university1st | 1.75 | 1.70 | 2.10 |

| university2nd | 5.27 | 2.80 | 21.30 |

| NA | 13.08 | 14.50 | 3.90 |

| disadvantages | |||

| school-leaver | 14.19 | 13.40 | 19.30 |

| longtimeunemployed | 27.29 | 24.50 | 45.40 |

| loweducation | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| noregularpaidjob | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.00 |

| childcare | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| drivinglicensegroup1 | 32.10 | 37.00 | 0.34 |

| drivinglicensegroup2 | 0.41 | 0.37 | 0.67 |

| drivinglicensegroup3 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| drivinglicensegroup4 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| drivinglicensegroup5 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| regionofpermanentresidence | |||

| Bratislava | 5.90 | 6.30 | 3.30 |

| Trnava | 9.13 | 9.10 | 9.30 |

| Trencin | 10.13 | 10.30 | 9.00 |

| Nitra | 12.33 | 12.30 | 12.50 |

| Zilina | 13.74 | 13.50 | 15.30 |

| BanskaBystrica | 13.27 | 13.20 | 13.70 |

| Presov | 19.42 | 18.90 | 22.80 |

| Kosice | 15.98 | 16.30 | 13.90 |

| Parameter | B | Std. Error | t | Sig. | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||

| Intercept | −826.157 | 68.217 | −12.111 | 0.000 | −959.861 | −692.452 |

| [gender_man] | 71.117 | 40.157 | 1.771 | 0.077 | −7.591 | 149.825 |

| [gender_woman] | 54.267 | 40.156 | 1.351 | 0.177 | −24.439 | 132.973 |

| [marital_status_single ] | 67.002 | 8.654 | 7.743 | 0.000 | 50.041 | 83.963 |

| [marital_status_married] | 69.916 | 9.090 | 7.692 | 0.000 | 52.100 | 87.733 |

| [marital_status_divorced] | 40.453 | 17.147 | 2.359 | 0.018 | 6.845 | 74.061 |

| [marital_status_widow] | −68.011 | 76.316 | −0.891 | 0.373 | −217.589 | 81.567 |

| [level_of_education_not finished] | 38.585 | 14.711 | 2.623 | 0.009 | 9.751 | 67.419 |

| [level_of_education_primary] | 55.567 | 13.383 | 4.152 | 0.000 | 29.336 | 81.797 |

| [level_of_education_lower secondary] | 70.235 | 15.174 | 4.629 | 0.000 | 40.494 | 99.976 |

| [level_of_education_secondary vocational] | 71.265 | 12.984 | 5.488 | 0.000 | 45.815 | 96.714 |

| [level_of_education_complete secondary vocational] | 65.378 | 12.926 | 5.058 | 0.000 | 40.044 | 90.713 |

| [level_of_education_upper secondary vocational] | 5.157 | 14.860 | 0.347 | 0.729 | −23.969 | 34.283 |

| [level_of_education_higher] | 30.986 | 18.486 | 1.676 | 0.094 | −5.248 | 67.219 |

| [level_of_education_university 1st] | −4.618 | 36.049 | −0.128 | 0.898 | −75.273 | 66.038 |

| [level_of_education_university 2nd] | 0.698 | 36.026 | 0.019 | 0.985 | −69.912 | 71.309 |

| [level_of_education_university 3rd] | −63.899 | 75.987 | −0.841 | 0.400 | −212.834 | 85.035 |

| [disadvantages_no] | −26.941 | 46.131 | −0.584 | 0.559 | −117.356 | 63.475 |

| [disadvantages_school-leaver] | −28.967 | 46.127 | −0.628 | 0.530 | −119.374 | 61.441 |

| [disadvantages_long time unemployed] | −28.341 | 46.097 | −0.615 | 0.539 | −118.691 | 62.010 |

| [disadvantages_low education] | 75.772 | 69.375 | 1.092 | 0.275 | −60.202 | 211.745 |

| [disadvantages_no regular paid job] | −22.515 | 53.835 | −0.418 | 0.676 | −128.030 | 83.000 |

| [disadvantages_child care] | 30.527 | 70.706 | 0.432 | 0.666 | −108.056 | 169.109 |

| [driving license_group1_no] | −3.953 | 11.308 | −0.350 | 0.727 | −26.117 | 18.210 |

| [driving license_group2_no] | 21.128 | 11.326 | 1.865 | 0.062 | −1.071 | 43.326 |

| [driving license_group3_no] | −28.934 | 9.421 | −3.071 | 0.002 | −47.399 | −10.469 |

| [driving license_group4_no] | 13.459 | 14.144 | 0.952 | 0.341 | −14.263 | 41.181 |

| [driving license_group5_no] | 4.162 | 8.073 | 0.515 | 0.606 | −11.661 | 19.984 |

| [region_Bratislava] | 168.495 | 18.452 | 9.131 | 0.000 | 132.329 | 204.662 |

| [region_Trnava] | 167.341 | 18.385 | 9.102 | 0.000 | 131.306 | 203.376 |

| [region_Trencin] | 153.800 | 18.378 | 8.369 | 0.000 | 117.781 | 189.820 |

| [region_Nitra] | 139.816 | 18.354 | 7.618 | 0.000 | 103.842 | 175.791 |

| [region_Zilina] | 141.493 | 18.343 | 7.714 | 0.000 | 105.541 | 177.444 |

| [region_Banska Bystrica] | 125.672 | 18.347 | 6.850 | 0.000 | 89.712 | 161.631 |

| [region_Presov] | 117.204 | 18.324 | 6.396 | 0.000 | 81.289 | 153.118 |

| [region_Kosice] | 132.310 | 18.333 | 7.217 | 0.000 | 96.378 | 168.242 |

| [school_1] | −40.347 | 13.386 | −3.014 | 0.003 | −66.583 | −14.111 |

| [school_2] | 58.183 | 18.888 | 3.080 | 0.002 | 21.162 | 95.204 |

| [school_3] | 40.541 | 20.335 | 1.994 | 0.046 | 0.684 | 80.398 |

| [school_4] | 30.391 | 17.372 | 1.749 | 0.080 | −3.659 | 64.440 |

| [school_5] | 16.707 | 16.172 | 1.033 | 0.302 | −14.990 | 48.403 |

| [school_6] | −1.082 | 29.275 | −0.037 | 0.971 | −58.462 | 56.297 |

| [school_7] | 31.478 | 16.028 | 1.964 | 0.050 | 0.063 | 62.893 |

| [school_8] | −6.986 | 47.122 | −0.148 | 0.882 | −99.344 | 85.372 |

| [school_9] | 81.595 | 30.567 | 2.669 | 0.008 | 21.685 | 141.505 |

| [school_10] | 17.261 | 17.970 | 0.961 | 0.337 | −17.959 | 52.482 |

| [school_11] | 0.464 | 35.533 | 0.013 | 0.990 | −69.181 | 70.109 |

| [school_12] | 62.308 | 24.203 | 2.574 | 0.010 | 14.870 | 109.746 |

| [school_13] | 51.315 | 15.806 | 3.247 | 0.001 | 20.336 | 82.294 |

| [school_14] | 28.298 | 15.864 | 1.784 | 0.074 | −2.795 | 59.390 |

| [school_15] | −56.627 | 101.547 | −0.558 | 0.577 | −255.658 | 142.405 |

| [school_16] | 5.064 | 83.397 | 0.061 | 0.952 | −158.393 | 168.522 |

| [school_17] | −91.687 | 21.849 | −4.196 | 0.000 | −134.510 | −48.865 |

| [school_18] | −189.438 | 35.828 | −5.287 | 0.000 | −259.660 | −119.216 |

| [school_19] | −3.973 | 19.787 | −0.201 | 0.841 | −42.755 | 34.809 |

| [school_20] | 42.552 | 15.988 | 2.662 | 0.008 | 11.217 | 73.888 |

| [school_21] | 22.919 | 16.446 | 1.394 | 0.163 | −9.315 | 55.152 |

| [school_22] | 5.896 | 18.100 | 0.326 | 0.745 | −29.580 | 41.372 |

| [school_23] | 46.937 | 16.663 | 2.817 | 0.005 | 14.278 | 79.596 |

| [school_24] | 78.390 | 115.830 | 0.677 | 0.499 | −148.635 | 305.415 |

| [school_25] | 85.485 | 27.919 | 3.062 | 0.002 | 30.765 | 140.206 |

| [school_26] | −35.728 | 37.628 | −0.950 | 0.342 | −109.478 | 38.021 |

| [school_27] | −44.091 | 42.487 | −1.038 | 0.299 | −127.366 | 39.184 |

| [school_28] | 34.412 | 37.712 | 0.913 | 0.362 | −39.503 | 108.327 |

| [school_29] | 10.975 | 40.458 | 0.271 | 0.786 | −68.322 | 90.271 |

| [school_30] | 21.377 | 37.754 | 0.566 | 0.571 | −52.620 | 95.374 |

| [school_31] | 1.265 | 38.374 | 0.033 | 0.974 | −73.947 | 76.478 |

| [school_32] | −11.596 | 41.047 | −0.283 | 0.778 | −92.047 | 68.855 |

| [school_33] | −9.776 | 38.562 | −0.254 | 0.800 | −85.357 | 65.805 |

| [school_34] | 27.574 | 38.906 | 0.709 | 0.478 | −48.680 | 103.829 |

| [school_35] | 17.305 | 38.444 | 0.450 | 0.653 | −58.044 | 92.655 |

| [school_36] | 41.112 | 38.703 | 1.062 | 0.288 | −34.746 | 116.970 |

| [school_37] | −20.469 | 42.500 | −0.482 | 0.630 | −103.769 | 62.830 |

| [school_38] | −95.066 | 51.466 | −1.847 | 0.065 | −195.938 | 5.806 |

| [school_39] | 37.513 | 44.333 | 0.846 | 0.397 | −49.378 | 124.405 |

| [school_40] | −26.530 | 38.524 | −0.689 | 0.491 | −102.037 | 48.978 |

| [school_41] | 14.967 | 16.005 | 0.935 | 0.350 | −16.403 | 46.336 |

| age_at_registration | −75.672 | 1.704 | −44.420 | 0.000 | −79.011 | −72.333 |

| evidence_length | −0.264 | 0.004 | −59.522 | 0.000 | −0.273 | −0.255 |

| previous_evidence_records | −0.108 | 0.009 | −12.416 | 0.000 | −0.126 | −0.091 |

| age_shifted | 103.376 | 1.656 | 62.413 | 0.000 | 100.129 | 106.622 |

| step2 | 278.185 | 4.540 | 61.280 | 0.000 | 269.287 | 287.082 |

| Parameter | B | Std. Error | t | Sig. | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||

| Intercept | −422.068 | 35.536 | −11.877 | 0.000 | −491.718 | −352.417 |

| [gender_man] | 26.993 | 20.919 | 1.290 | 0.197 | −14.008 | 67.993 |

| [gender_woman] | 30.689 | 20.918 | 1.467 | 0.142 | −10.311 | 71.688 |

| [marital_status_single ] | 34.807 | 4.508 | 7.721 | 0.000 | 25.972 | 43.643 |

| [marital_status_married] | 40.509 | 4.735 | 8.555 | 0.000 | 31.228 | 49.790 |

| [marital_status_divorced] | 44.160 | 8.932 | 4.944 | 0.000 | 26.653 | 61.668 |

| [marital_status_widow] | 12.023 | 39.755 | 0.302 | 0.762 | −65.897 | 89.942 |

| [level_of_education_not finished] | 19.318 | 7.664 | 2.521 | 0.012 | 4.298 | 34.339 |

| [level_of_education_primary] | 28.069 | 6.972 | 4.026 | 0.000 | 14.405 | 41.733 |

| [level_of_education_lower secondary] | 36.165 | 7.905 | 4.575 | 0.000 | 20.672 | 51.658 |

| [level_of_education_secondary vocational] | 40.389 | 6.764 | 5.971 | 0.000 | 27.132 | 53.646 |

| [level_of_education_complete secondary vocational] | 32.092 | 6.733 | 4.766 | 0.000 | 18.894 | 45.290 |

| [level_of_education_upper secondary vocational] | −3.999 | 7.741 | −0.517 | 0.605 | −19.171 | 11.173 |

| [level_of_education_higher] | 11.406 | 9.630 | 1.184 | 0.236 | −7.468 | 30.281 |

| [level_of_education_university 1st] | 8.356 | 18.779 | 0.445 | 0.656 | −28.450 | 45.162 |

| [level_of_education_university 2nd] | −7.704 | 18.767 | −0.411 | 0.681 | −44.487 | 29.079 |

| [level_of_education_university 3rd] | −47.247 | 39.584 | −1.194 | 0.233 | −124.831 | 30.337 |

| [disadvantages_no] | −15.545 | 24.031 | −0.647 | 0.518 | −62.645 | 31.555 |

| [disadvantages_school-leaver] | −24.566 | 24.029 | −1.022 | 0.307 | −71.662 | 22.530 |

| [disadvantages_long time unemployed] | −24.774 | 24.013 | −1.032 | 0.302 | −71.839 | 22.292 |

| [disadvantages_low education] | 26.475 | 36.139 | 0.733 | 0.464 | −44.357 | 97.307 |

| [disadvantages_no regular paid job] | −12.384 | 28.044 | −0.442 | 0.659 | −67.350 | 42.582 |

| [disadvantages_child care] | 27.312 | 36.832 | 0.742 | 0.458 | −44.879 | 99.503 |

| [driving license_group1_no] | −2.088 | 5.891 | −0.354 | 0.723 | −13.633 | 9.458 |

| [driving license_group2_no] | 9.891 | 5.900 | 1.676 | 0.094 | −1.673 | 21.455 |

| [driving license_group3_no] | −22.070 | 4.908 | −4.497 | 0.000 | −31.689 | −12.451 |

| [driving license_group4_no] | 6.524 | 7.368 | 0.886 | 0.376 | −7.917 | 20.965 |

| [driving license_group5_no] | 5.632 | 4.205 | 1.339 | 0.180 | −2.610 | 13.875 |

| [region_Bratislava] | 81.686 | 9.612 | 8.498 | 0.000 | 62.845 | 100.526 |

| [region_Trnava] | 85.582 | 9.577 | 8.936 | 0.000 | 66.811 | 104.354 |

| [region_Trencin] | 82.983 | 9.573 | 8.668 | 0.000 | 64.219 | 101.747 |

| [region_Nitra] | 76.428 | 9.561 | 7.994 | 0.000 | 57.689 | 95.168 |

| [region_Zilina] | 74.467 | 9.555 | 7.793 | 0.000 | 55.739 | 93.195 |

| [region_Banska Bystrica] | 66.437 | 9.557 | 6.951 | 0.000 | 47.705 | 85.169 |

| [region_Presov] | 64.158 | 9.545 | 6.721 | 0.000 | 45.450 | 82.867 |

| [region_Kosice] | 72.452 | 9.550 | 7.587 | 0.000 | 53.734 | 91.170 |

| [school_1] | −25.684 | 6.973 | −3.683 | 0.000 | −39.351 | −12.017 |

| [school_2] | 30.506 | 9.839 | 3.100 | 0.002 | 11.221 | 49.792 |

| [school_3] | 25.088 | 10.593 | 2.368 | 0.018 | 4.325 | 45.850 |

| [school_4] | 13.333 | 9.050 | 1.473 | 0.141 | −4.404 | 31.070 |

| [school_5] | 12.734 | 8.424 | 1.512 | 0.131 | −3.778 | 29.246 |

| [school_6] | −0.932 | 15.250 | −0.061 | 0.951 | −30.822 | 28.959 |

| [school_7] | 13.762 | 8.350 | 1.648 | 0.099 | −2.603 | 30.127 |

| [school_8] | 16.521 | 24.547 | 0.673 | 0.501 | −31.590 | 64.633 |

| [school_9] | 61.592 | 15.923 | 3.868 | 0.000 | 30.384 | 92.801 |

| [school_10] | 10.516 | 9.361 | 1.123 | 0.261 | −7.831 | 28.863 |

| [school_11] | 0.339 | 18.510 | 0.018 | 0.985 | −35.941 | 36.619 |

| [school_12] | 24.289 | 12.608 | 1.926 | 0.054 | −0.423 | 49.000 |

| [school_13] | 24.016 | 8.234 | 2.917 | 0.004 | 7.879 | 40.154 |

| [school_14] | 15.684 | 8.264 | 1.898 | 0.058 | −0.513 | 31.881 |

| [school_15] | −0.794 | 52.899 | −0.015 | 0.988 | −104.475 | 102.887 |

| [school_16] | 41.456 | 43.444 | 0.954 | 0.340 | −43.693 | 126.606 |

| [school_17] | −55.766 | 11.381 | −4.900 | 0.000 | −78.074 | −33.459 |

| [school_18] | −90.171 | 18.664 | −4.831 | 0.000 | −126.752 | −53.591 |

| [school_19] | 2.489 | 10.307 | 0.241 | 0.809 | −17.714 | 22.691 |

| [school_20] | 15.820 | 8.328 | 1.899 | 0.058 | −0.504 | 32.143 |

| [school_21] | 11.379 | 8.567 | 1.328 | 0.184 | −5.412 | 28.171 |

| [school_22] | −1.783 | 9.429 | −0.189 | 0.850 | −20.263 | 16.698 |

| [school_23] | 23.500 | 8.680 | 2.707 | 0.007 | 6.487 | 40.513 |

| [school_24] | 81.193 | 60.339 | 1.346 | 0.178 | −37.070 | 199.457 |

| [school_25] | 42.132 | 14.544 | 2.897 | 0.004 | 13.626 | 70.637 |

| [school_26] | −30.943 | 19.601 | −1.579 | 0.114 | −69.361 | 7.476 |

| [school_27] | −48.867 | 22.133 | −2.208 | 0.027 | −92.247 | −5.487 |

| [school_28] | −14.570 | 19.645 | −0.742 | 0.458 | −53.074 | 23.935 |

| [school_29] | −24.319 | 21.075 | −1.154 | 0.249 | −65.627 | 16.988 |

| [school_30] | −16.326 | 19.667 | −0.830 | 0.406 | −54.873 | 22.221 |

| [school_31] | −18.975 | 19.990 | −0.949 | 0.343 | −58.155 | 20.205 |

| [school_32] | −23.652 | 21.382 | −1.106 | 0.269 | −65.561 | 18.257 |

| [school_33] | −23.117 | 20.088 | −1.151 | 0.250 | −62.489 | 16.256 |

| [school_34] | −18.945 | 20.267 | −0.935 | 0.350 | −58.668 | 20.777 |

| [school_35] | −12.171 | 20.026 | −0.608 | 0.543 | −51.423 | 27.080 |

| [school_36] | −13.195 | 20.161 | −0.654 | 0.513 | −52.711 | 26.322 |

| [school_37] | −23.817 | 22.139 | −1.076 | 0.282 | −67.210 | 19.576 |

| [school_38] | −54.849 | 26.810 | −2.046 | 0.041 | −107.396 | −2.302 |

| [school_39] | −2.892 | 23.094 | −0.125 | 0.900 | −48.157 | 42.372 |

| [school_40] | −35.351 | 20.068 | −1.762 | 0.078 | −74.685 | 3.982 |

| [school_41] | 9.627 | 8.337 | 1.155 | 0.248 | −6.715 | 25.968 |

| age_at_registration | −42.152 | 0.887 | −47.498 | 0.000 | −43.891 | −40.412 |

| evidence_length | −0.144 | 0.002 | −62.430 | 0.000 | −0.149 | −0.140 |

| previous_evidence_records | −0.059 | 0.005 | −12.877 | 0.000 | −0.067 | −0.050 |

| age_shifted | 56.925 | 0.863 | 65.976 | 0.000 | 55.234 | 58.616 |

| step2 | 138.742 | 2.365 | 58.670 | 0.000 | 134.107 | 143.377 |

References

- Lambovska, M.; Sardinha, B.; Belas, J., Jr. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Youth Unemployment in the European Union. Ekon.-Manaz. Spektrum 2021, 15, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastuvkova, L. Active Labour Market Policy [Aktívna Politika Trhu Práce]; Personnel and Payroll Consultant: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. OECD Glossary of Statistical Terms-Active Labour Market Programmes Definition. Available online: https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=28 (accessed on 8 April 2020).

- International Labour Office; Social Security Department. Social Security to All: The Strategy of the International Labour Organization: Building Social Protection Floors and Comprehensive Social Security Systems; ILO: Geneva, The Switzerland, 2012; ISBN 978-92-2-126746-1. [Google Scholar]

- Pignatti, C.; Belle, E.V. Better Together: Active and Passive Labour Market Policies in Developed and Developing Economies. Res. Dep. Work. Pap. 2018, 37, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valaskova, K.; Durana, P.; Adamko, P. Changes in Consumers’ Purchase Patterns as a Consequence of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, M.; Callis, Z.; Flatau, P.; Kaleveld, L. COVID-19 and Youth Unemployment—CSI Response 2020. Available online: https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2020-05/apo-nid305943.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Valaskova, K.; Kliestik, T.; Gajdosikova, D. Distinctive Determinants of Financial Indebtedness: Evidence from Slovak and Czech Enterprises. Equilib. Q. J. Econ. Econ. Policy 2021, 16, 639–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svabova, L.; Metzker, Z.; Pisula, T. Development of Unemployment in Slovakia in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ekon.-Manaz. Spektrum 2020, 14, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Office. Emploi et Questions Sociales Dans Le Monde: Tendances 2022; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 978-92-2-035702-6. [Google Scholar]

- COLSAF SR Monthly Statistics on the Number and Structure of Jobseekers in Slovakia [Mesačné Štatistiky o Počte a Štruktúre Uchádzačov o Zamestnanie]. Available online: https://www.upsvr.gov.sk/statistiky/nezamestnanost-absolventi-statistiky/kopia-2018.html?page_id=915559 (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- COLSAF SR Unemployment-Monthly Statistics [Nezamestnanosť-Mesačné Štatistiky ]. Available online: https://www.upsvr.gov.sk/buxus/generate_page.php?page_id=855042 (accessed on 8 April 2020).

- Act No. 5/2004 Coll. on Employment Services and on Amending Certain Laws; International Labour Organization (ILO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2004.

- Act No. 523/2004 Coll. the Act on Budgetary Rules of the Public Administration and on Amending Certain Laws; International Labour Organization (ILO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2004.

- Jaskova, D.; Haviernikova, K. The Human Resources as an Important Factor of Regional Development. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2020, 21, 1464–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popirlan, C.-I.; Tudor, I.-V.; Dinu, C.-C.; Stoian, G.; Popirlan, C.; Danciulescu, D. Hybrid Model for Unemployment Impact on Social Life. Mathematics 2021, 9, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroleo, F.E.; Ciociano, E.; Destefanis, S. Youth Labour-Market Performance, Institutions and Vet Systems: A Cross-Country Analysis. Ital. Econ. J. 2017, 3, 39–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martincova, M. Youth Unemployment in the Labor Market of Slovak Republic. In Proceedings of the SGEM2016 Conference Proceedings, Albena, Bulgaria, 30 June–6 July 2016; Volume 2, pp. 937–944. [Google Scholar]

- Picatoste, X.; Rodriguez-Crespo, E. Decreasing Youth Unemployment as a Way to Achieve Sustainable Development. In Decent Work and Economic Growth; Leal Filho, W., Azul, A.M., Brandli, L., Lange Salvia, A., Wall, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 244–253. ISBN 978-3-319-95867-5. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanik, M.; Lubyova, M.; Dovalova, G.; Karasova, K. Analysis of the Effects of Active Labor Market Policy Measures [Analýza Účinkov Nástrojov Aktívnej Politiky Trhu Práce]; The Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs and Family of the Slovak Republic: Bratislava, Slovak, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Svabova, L.; Kramarova, K. An Analysis of Participation Factors and Effects of the Active Labour Market Measure Graduate Practice in Slovakia-Counterfactual Approach. Eval. Program Plan. 2021, 86, 101917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamesberger, D.; Bacher, J. COVID-19 Crisis: How to Avoid a ‘Lost Generation’. Intereconomics 2020, 55, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selicka, D. Young People and Unemployment [Mladí Ľudia a Nezamestnanosť]. Mlad. Spol. 2018, 2, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wolbers, M.H.J. Patterns of Labour Market Entry: A Comparative Perspective on School-to-Work Transitions in 11 European Countries. Acta Sociol. 2007, 50, 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mascherini, M.; Ludwinek, A.; Vacas-Soriano, C.; Meierkord, A.; Gebel, M. Mapping Youth Transitions in Europe. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/report/2014/labour-market/mapping-youth-transitions-in-europe (accessed on 8 April 2020).

- Vuolo, M.; Staff, J.; Mortimer, J.T. Weathering the Great Recession: Psychological and Behavioral Trajectories in the Transition from School to Work. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 48, 1759–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gorlich, A.; Katznelson, N. Young People on the Margins of the Educational System: Following the Same Path Differently. Educ. Res. 2018, 60, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, H. Youth Unemployment in Europe: Theoretical Considerations and Empirical Findings; Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gontkovicova, B.; Mihalcova, B.; Pruzinsky, M. Youth Unemployment—Current Trend in the Labour Market? Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 23, 1680–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gajanova, L.; Nadanyiova, M.; Musat, M.; Bogdan, A. The Social Recruitment As a New Opportunity in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. EMS 2020, 14, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liotti, G. Labour Market Flexibility, Economic Crisis and Youth Unemployment in Italy. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2020, 54, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbling, L.A.; Sacchi, S.; Imdorf, C. Comparing Long-Term Scarring Effects of Unemployment across Countries: The Impact of Graduating during an Economic Downturn. Negot. Early Job Insecurity 2019, 68–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blazek, J.; Netrdova, P. Regional Unemployment Impacts of the Global Financial Crisis in the New Member States of the EU in Central and Eastern Europe. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2012, 19, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verick, S. Who Is Hit Hardest During a Financial Crisis? The Vulnerability of Young Men and Women to Unemployment in an Economic Downturn; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tanveer Choudhry, M.; Marelli, E.; Signorelli, M. Youth Unemployment Rate and Impact of Financial Crises. Int. J. Manpow. 2012, 33, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D.N.F.; Blanchflower, D.G. Young People and the Great Recession. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2011, 27, 241–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laska, I. The Pandemic Threatened Graduates [Pandémia Ohrozila Absolventov]; Hospodárske noviny: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Svabova, L.; Durica, M.; Kramarova, K.; Valaskova, K.; Janoskova, K. Employability and Sustainability of Young Graduates in the Slovak Labour Market: Counterfactual Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aaronson, S.; Alba, F. Unemployment among Young Workers during COVID-19; Brookings: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Office ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the World of Work, 4th ed.; Updated Estimates and Analysis; ILO: Genève, Switzerland, 2020.

- Elia, L.; Santangelo, G.; Schnepf, S.V. Synthesis Report on the Call ‘Pilot Projects to Carry out ESF Related Counterfactual Impact Evaluations’; ILO: Genève, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Potluka, O.; Bruha, J.; Spacek, M.; Vrbova, L. Counterfactual Impact Evaluation on EU Cohesion Policy Interventions in Training in Companies. Ekon. Cas. 2016, 64, 575–595. [Google Scholar]

- Regulation (EU) No 1303/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013 Laying down Common Provisions on the European Regional Development Fund, the European Social Fund, the Cohesion Fund, the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund and Laying down General Provisions on the European Regional Development Fund, the European Social Fund, the Cohesion Fund and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund and Repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 1083/2006. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32013R1303 (accessed on 7 September 2021).

- Biewen, M.; Fitzenberger, B.; Osikominu, A.; Paul, M. The Effectiveness of Public-Sponsored Training Revisited: The Importance of Data and Methodological Choices. J. Labor Econ. 2014, 32, 837–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lechner, M.; Wiehler, S. Does the Order and Timing of Active Labor Market Programs Matter? IZA Discussion Paper; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; p. 3092. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, J.; Stephan, G. Subsidized Work before and after the German Hartz Reforms: Design of Major Schemes, Evaluation Results and Lessons Learnt. IZA J. Labor Policy 2013, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caliendo, M.; Schmidl, R. Youth Unemployment and Active Labor Market Policies in Europe. IZA J. Labor Policy 2016, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duranti, S.; Maitino, M.L.; Patacchini, V.; Rampichini, C.; Sciclone, N. What Training for the Unemployed? An Impact Evaluation for Targeting Training Courses. Politica Econ. 2018, 241–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluve, J.; Puerto, S.; Robalino, D.; Romero, J.M.; Rother, F.; Stöterau, J.; Weidenkaff, F.; Witte, M. Interventions to Improve the Labour Market Outcomes of Youth: A Systematic Review of Training, Entrepreneurship Promotion, Employment Services and Subsidized Employment Interventions. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2017, 13, 1–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burda, M.C.; Lubyova, M. The Impact of Active Labour Market Policies: A Closer Look at the Czech and Slovak Republics; Centre for Economic Policy Research: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Borik, V.; Caban, M. Pilot Impact Evaluation of Selected Active Labor Market Policy Measures [Pilotné Hodnotenie Dopadov Vybraných Opatrení Aktívnej Politiky Trhu Práce]; MLSAF: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Harvan, P. Evaluation of Efficiency and Effectiveness of Active Labor Market Policy Expenditures in Slovakia [Hodnotenie Efektívnosti a Účinnosti Výdavkov na Aktívne Politiky Trhu Práce na Slovensku]; IFP: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Moravcikova, K. Graduate Practice as a Labor Market Intervention to Tackle Youth Unemployment in Slovakia [Absolventská Prax Ako Nástroj Trhu Práce Na Riešenie Nezamestnanosti Mladých Na Slovensku]. In Proceedings of the Nové Výzvy Pre Sociálnu Politiku a Globálny Trh Práce 2015, Veľký Meder, Slovensko, 14–15 May 2015; Trexima: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Svabova, L.; Durica, M.; Kliestik, T. Modeling the Unemployment Costs of Young Graduates in Slovakia: A Counterfactual Approach [Modelovanie Nákladov Nezamestnanosti Mladých Absolventov Na Slovensku: Kontrafaktuálny Prístup]. Politická Ekon. 2019, 67, 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- KPMG. Counterfactual Impact Evaluation Methods; Kontrafaktuálne Metódy Hodnotenia Dopadov: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Albanese, A.; Cappellari, L.; Leonardi, M. The Effects of Youth Labour Market Reforms: Evidence from Italian Apprenticeships. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 2021, 73, 98–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frondel, M.; Schmidt, C.M. Evaluating Environmental Programs: The Perspective of Modern Evaluation Research. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 55, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kruppe, T.; Lang, J. Labour Market Effects of Retraining for the Unemployed: The Role of Occupations. Appl. Econ. 2018, 50, 1578–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morgan, S.L.; Winship, C. Counterfactuals and Causal Inference: Methods and Principles for Social Research. In Analytical Methods for Social Research, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-107-06507-9. [Google Scholar]

- Trivellato, U. Fifteen Years of Labour Market Regulations and Policies in Italy: What Have We Learned from Their Evaluation? Statistica 2011, 71, 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerulli, G. Econometric Evaluation of Socio-Economic Programs: Theory and Applications; Advanced Studies in Theoretical and Applied Econometrics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; ISBN 978-3-662-46404-5. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data; The MIT Press: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-0-262-23258-6. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M. Matching, Regression Discontinuity, Difference in Differences, and Beyond; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-0-19-025874-0. [Google Scholar]

- CRIE Handout for the Training Workshop on Counterfactual Impact Evaluation; CRIE: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2014.

- Stefanik, M.; Karasova, K.; Studena, I. Can Supporting Workplace Insertions of Unemployed Recent Graduates Improve Their Long-Term Employability? Empirica 2020, 47, 245–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J. Micro-Econometrics: Methods of Moments and Limited Dependent Variables, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-387-95376-2. [Google Scholar]

- Trading Economics Slovakia Youth Unemployment Rate. Available online: https://tradingeconomics.com/slovakia/youth-unemployment-rate (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- OECD. OECD Economic Surveys; Slovak Republic: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- COLSAF SR. Evaluation of the Implementation of Active Labour Market Measures in 2020 [Vyhodnotenie Uplatnovania Aktivnych Opatreni Na Trhu Prace Za Rok 2020]; COLSAF SR: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Act No. 601/2003 Coll. on Subsistence Minimum and on Amending Certain Laws; International Labour Organization (ILO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- Act No. 663/2007 Coll on the Minimum Wage and on Amending Certain Laws; International Labour Organization (ILO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

| Variable Name | Description |

|---|---|

| ID | Anonymized identification code of each individual |

| Intervention | Attending the Graduate practice |

| School code | Last finished school according to the list of study and vocational fields |

| Age at registration | Age of each individual on the date of entry into the database of jobseekers |

| Previous evidence | Sum of days of all previous registrations of the individual in the database of jobseekers |

| Profession before registration | Last profession before the individual’s registration according to the international classification of occupations ISCO-08 |

| Start of registration | Date of entry into the database of jobseekers |

| End of registration | Date of termination from the database of jobseekers |

| Evidence length | Number of days of the last evidence in the database of jobseekers |

| Start of intervention | Date of start of the participation in the Graduate practice (if) |

| End of intervention | Date of termination of the participation in the Graduate practice (if) |

| Duration of intervention | Number of days of participation in the Graduate practice (if) |

| Grant | Sum of allowances paid during the Graduate practice |

| Age shifted | Age of the individual shifted from the start of the registration in the database of jobseekers to the date of the start of the participation in the Graduate practice (for the treated participants) or to 1st October 2015 (for non-treated jobseekers) |

| Gender | Gender of each individual |

| Marital status | Marital status at the time of the individual’s entry in the database of jobseekers (single, married, divorced, widow/widowed, or not specified) |

| Level of education | Highest degree of education at the time of the individual´s entry into the database of jobseekers (10 levels of education from unfinished primary education to the highest level of higher education, plus the category not specified) |

| Region of residence | Region of the permanent residence at the time of the individual´s entry in the database of jobseekers (Bratislava, Trnava, Trencin, Nitra, Zilina, Banska Bystrica, Presov, Kosice, plus category not specified) |

| Disadvantages | Disadvantage of jobseekers under Section 8 of Act on employment services [13] (other than the status “school graduate”, i.e., a long-term unemployed individual who has completed education lower than the secondary vocational education, individual living as a single adult with one or more people dependent on their care or caring for at least one child before the end of compulsory schooling, disabled person, plus category no disadvantage) |

| Last school | Type of the last (attended) school of the individual at the time of the entry into the database of jobseekers |

| Driving license group 1 | Ownership of the driving license for motorcycles (categories AM, A1 and A; binary type of variable—0 if the individual does not own the driving license of a given category, 1 if the individual owns the driving license of given category) |

| Driving license group 2 | Ownership of the driving license for cars and small lorries (categories B1, B and B + E; binary type of variable—0 if the individual does not own the driving license of a given category, 1 if the individual owns the driving license of given category) |

| Driving license group 3 | Ownership of the driving license for trucks (categories C1, C1 + E, C and C + E; binary type of variable—0 if the individual does not own the driving license of a given category, 1 if the individual owns the driving license of given category) |

| Driving license group 4 | Ownership of the driving license for lorries and buses (categories D1, D1 + E, D and D + E; binary type of variable—0 if the individual does not own the driving license of a given category, 1 if the individual owns the driving license of given category) |

| Driving license group 5 | Ownership of the driving license for tractors (category T; binary type of variable—0 if the individual does not own the driving license of a given category, 1 if the individual owns the driving license of given category) |

| Period of Validity | Conditions of the Intervention | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of the Jobseeker/Conditions of the Evidence | Duration of the Intervention | Monthly Allowance | |

| April 2004–April 2008 | <25 years | up to 6 months, possible repetition 1 year after the previous Graduate practice | 56,43 EUR (fixed amount) |

| May 2008–December2010 | |||

| January 2011–June 2011 | <25 years | 3–6 months, 20 h a week, repetition is not possible | based on the statutory amount of the subsistence minimum |

| July 2011–April 2013 | <26 years | ||

| registered in the Register of jobseekers for at least three months | |||

| from May 2013 | <26 years | ||

| registered in the Register of jobseekers for at least one month | |||

| Period | 2013 to 2nd Quarter of 2017 | 3rd Quarter 2017 to 2nd Quarter 2018 | 3rd Quarter 2018 to 2nd Quarter 2019 | 3rd Quarter 2019 to 2nd Quarter 2020 | 3rd Quarter 2020 to 2nd Quarter 2021 | 3rd Quarter 2021 to 2nd Quarter 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subsistence minimum (1 adult person) in EUR | 198.09 | 199.48 | 205.07 | 210.20 | 214.83 | 2018.06 |

| Allowance in EUR | 128.75 | 129.66 | 133.30 | 136.63 | 139.64 | 141.74 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Svabova, L.; Kramarova, K. Allowance for School Graduate Practice Performance in Slovakia: Impact Evaluation of the Intervention. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1442. https://doi.org/10.3390/math10091442

Svabova L, Kramarova K. Allowance for School Graduate Practice Performance in Slovakia: Impact Evaluation of the Intervention. Mathematics. 2022; 10(9):1442. https://doi.org/10.3390/math10091442

Chicago/Turabian StyleSvabova, Lucia, and Katarina Kramarova. 2022. "Allowance for School Graduate Practice Performance in Slovakia: Impact Evaluation of the Intervention" Mathematics 10, no. 9: 1442. https://doi.org/10.3390/math10091442

APA StyleSvabova, L., & Kramarova, K. (2022). Allowance for School Graduate Practice Performance in Slovakia: Impact Evaluation of the Intervention. Mathematics, 10(9), 1442. https://doi.org/10.3390/math10091442