1. Introduction

Portfolio selection has been a popular topic since the introduction of modern portfolio theory or the mean-variance theory (MVT) [

1] of the Nobel prize winner economist Harry Markowitz. MVT states that investors rationally select portfolios based on risk-return trade-offs such that given investments of similar risks (returns), investors will always prefer the investment with the highest return (smallest risk) over the given choices. However, it is argued that many investors have their personal preferences or bias, leading to the emergence of behavioral finance and behavioral portfolio theory (BPT) [

2]. Individual perception plays a huge role in BPT. BPT asserts that behavioral investors frame investments into different mental accounts (MAs) corresponding to the risk and return objectives. BPT investors use a safety-first portfolio selection model in selecting their portfolio based on their tolerance of loss and the corresponding probability. When we look at future returns, investors, based on their perception, provide estimates on future performances of the market and the underlying securities within it. SP/A theory of [

3] claims that individuals give probability weights on scenarios based on their fear and hope levels. Individuals give more weight to bad (good) scenarios when they are in fear (hopeful). When selecting the security, it is assumed that investors are always looking for securities with higher return rates or lower risks. However, the investor may sell the security with an increasing return rate because they are afraid of the future drop in the price; they may withhold the security with decreasing rates because they think the price eventually will return to what it was. The potential collective influence of irrational behaviors may stimulate stock prices and likely cause price distortions. These studies led to the framework of behavioral portfolio optimization.

The behavioral portfolio optimization framework comprises 3 parts, return estimation, return weighting, and mental accounts (MAs) selection. In the return estimation phase, an investor will have an estimate of the future performances of the considered investment pool. Then, the investor would assign corresponding probabilities of the estimated returns. Subsequently, the investor would then use the appropriate portfolio selection model to get the optimal portfolio for each of his/her MA. Again each mental account corresponds to a specific goal (returns) and risk level [

4]. Behavioral portfolio models incorporate behavioral biases in investing considering different or multiple return objectives intended for family, retirement savings, emergency funds, etc. [

5]. Moreover, ref. [

6] stated that behavioral portfolio management or BPM is the superior way to make investment decisions. The main concept in BPM is that investors tend to be emotional, which can affect the price movement. Knowing this effect, superior portfolios can be built by studying the irrational behaviors of investors and seeing how they affect the price movement. There are many studies like [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11] providing proof that irrational behavior exists among investors. Still, there are limited studies that show how these irrational behaviors can be exploited to have a superior portfolio. There are several irrational behaviors among investors, but in this study, 5 irrational behaviors are considered in generating superior portfolios. The first bias considered is the Disposition effect.

The disposition effect (DE) may be observed when investors, for some irrational reason, sell winning stocks too early and hold on to losing stocks too long. It can be placed into a broader theoretical framework that the aforementioned is the general disposition of all investors [

12]. In this framework, the investor is more concerned with avoiding loss than realizing gain; this happens when the investor has not yet moved on from the pain of losing previous investments [

8]. DE happens when investors consider investments on a loss or gain perspective rather than the final wealth levels [

7]. The second irrational behavior examined is overreaction among investors.

Over-reaction (OR) is the irrational behavior of investors to overreact to recent positive or negative news. An earlier study on OR done by [

9] analyzed the abnormal returns of winner (portfolios that are profiting) and loser (portfolios that are losing) portfolios and observed performance reversals. Following this study, ref. [

13] showed the existence of OR through the identification of seasonal patterns of returns showing that past losers significantly outperform past winners. It was observed by [

10] that loser portfolios dominate winner portfolios after 4 years using data from the Tokyo stock exchange. Similarly, ref. [

14], in 1 week, spotted return reversals after sudden large price changes. In a study of the Hong Kong market considering the pre and post-Asian financial crisis by [

15], they observed statistically significant patterns of price reversals 2 days after a substantial price change. Using Nasdaq and NYSE data, ref. [

16] also identified significant reversals after a large price change for Nasdaq (1–2 days) but not for NYSE. Studying exchange-traded funds (ETFs), ref. [

17] also encountered pronounce price corrections (or reversals) after extreme price changes. If there is over-reaction, then we also have under-reaction among investors.

Under-reaction (UR) is the irrational behavior of investors to under-react to recent positive or negative news. The concept of UR is the opposite of over-reaction. According to [

18], under-reaction (over-reaction) is observed in unstable (stable) markets with precise (noisy) signals. Earlier works of [

11,

19,

20,

21,

22] show evidence wherein the market response to significant new information seems to be too late or too little. Moreover, refs. [

19,

20] provided evidence that financial analysts under-react to the announcement of earnings such that they over-estimate (under-estimate) quarterly earnings after positive (negative) surprises. It was also observed by [

11] that price responses to dividend cuts and or initiations tend to continue for an extreme and irrational long period. Usually, UR is studied together with OR. Intuitively, if in OR the focus is the price reversal after a significant large price movement, then for UR, continuous performance with the same direction is expected. Another irrational behavior prevalent among investors is the ostrich effect.

The term “ostrich effect” has been used in studies of financial decision-making, where it signifies investors’ willingness to “avoid risky financial situations by pretending that they do not exist”. Ref. [

23] states that it is the avoidance of apparently risky financial situations by pretending they do not exist. Ostrich Effect (OE) is the irrational behavior of investors to avoid unfavorable information about their portfolio. It is the behavior of avoiding exposing oneself to [financial] information that one fear may cause psychological discomfort. For example, in a market downturn, people may avoid monitoring their investments or seeking other financial news [

24]. Monitoring one’s current standing concerning goals can promote effective self-regulation. However, the present review suggests that there is an ostrich problem such that, in many instances, people tend to “bury their head in the sand” and intentionally avoid or reject information that would help them to monitor their goal progress [

25]. In OE, people would rather move away from disturbing situations, which seem difficult, frightening, and even dangerous [

26]. An individual prefers not to obtain information about her state of affairs because of the fear that she may receive bad news, despite the prospect of making better decisions based on this information [

27]. Lastly, we have the herding bias among investors.

Herding is the bias wherein a large group of individuals is doing the same investment action. Herding behavior is also defined by [

28] as “everyone doing what everyone else is doing, even when their private information suggests doing something quite different.”. The work of [

29] pointed out that in its most general form, herding could be defined as behavior patterns correlated across individuals. Still, such behavior patterns could be due to correlated information arrival in independently acting individuals. The type of herding behavior most interesting to researchers and widely studied in stock trading and online auctions, as in [

30], is caused by informational cascades. Informational cascades occur “when it is optimal for an individual, having observed the actions of those ahead of him, to follow the behavior of the preceding individual without regard to his information” [

31]. In other related works by [

32,

33,

34] and many other researchers define herding as following others’ decisions and using stock returns to test the existence of herd behavior.

Considering all these irrational behaviors, the question is how we exploit them to generate superior portfolios, as BPM implied. As mentioned, most related literature just tries to identify the existence of these biases. Still, there are limited studies on how these irrational behaviors can be utilized to generate optimal portfolios. To the authors’ knowledge, only the proposed behavioral stock portfolio optimization proposed by [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39] deals with the identification of the cause-and-effect relationship of a collective investor behavior with a stock price movement. It then exploits the information to generate superior portfolios. They call the stocks with a significant cause-and-effect relationship with an investor bias and price movement behavioral stocks or B-stocks.

B-stocks are defined by identifying the cause (trigger point) and effect (e.g., cumulative abnormal return becomes positive) relationships or patterns between a collective irrational behavior of investors and a stock price movement. Moreover, the corresponding likelihood of occurrence (

PBs) and time duration (

T-days) between the cause and effect are also tested and known. Because we can identify the cause-effect pattern of B-stocks, it makes B-stocks predictable and can be considered a good investment pool in portfolio selection. In general, a B-stock contains the information of a cause-effect-

PB-

T pattern. From the operational definitions (ODs) of irrational behavior available in related literature, we can identify the cause-and-effect relationship between a stock’s price movement and the effect of the tested behavior. For example, a large price change can represent the cause of the behavior, and a follow-up price reversal can be the ensuing effect. It is also essential to know when the effect will occur after a cause is spotted and the probability that the effect will occur after the said time duration. This is done by looking at the historical data and counting the occurrence of the expected effect after possible causes. Then, using a statistical test, we can verify whether the proportion of occurrence with the possible causes is more than a threshold probability. Those stocks that show a significant cause-and-effect pattern with the corresponding

T-days and

are then considered into the B-stock big pool. Depending on the investment strategy, this big pool can be further screened into smaller pools. Since it is known when the effect will occur, one strategy is to invest 1 day before the effect day or during (

T − 1)th day. Another strategy is to invest immediately after spotting the cause and exit on the effect day or

T-day. For the 1st strategy, the investment pool (small pool 1) are those B-stocks in the big pool that are already on their (

T − 1)th on a given trading day. Similarly, for the 2nd strategy, the investment pool (small pool 2) are those B-stocks in the big pool that have their causes spotted on a given trading day. The unique information embedded within these B-stocks is then exploited to have superior portfolios as done by these 5 studies [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39].

The initial idea of B-stocks was first introduced by [

35]. The study considered two irrational behaviors (over-reaction and under-reaction) in identifying significant cause-effect-

PB-

T patterns. They exploit the over-reaction and under-reaction B-stocks by considering the small pool 1 investment pool and long position (buy-hold-sell) investment strategy. Regarding return estimation, historical returns were used as return estimates and scenarios. With the assignment of probability weights, SP/A (security, potential, and aspiration) theory is applied to give corresponding probabilities to the return scenarios. The study also proposed the initial concept of a two-dimensional probability weighting which considers the scenarios weights and also the

PB weights of individual B-stocks. This 2-D weighting mechanism was embedded into the generic safety-first scenario-based portfolio selection model to generate the optimal portfolio. The model ensures that scenario weights and the likelihood of each B-stock realizing the expected effect or

PB are consistent with their respective probabilities such that the optimal portfolio will have the highest combined

PB. Then through back-testing, their results show that this framework can outperform benchmarks (e.g., mean-variance portfolio) and the market. The study only considers small pool 1, so the question now can small pool 2 also generate superior portfolios?

The next study [

36] on behavioral stocks answers whether small pool 2 can also generate superior portfolios. The study considered two irrational behaviors, which are over-reaction and disposition effect. The main difference from the previous study is that this study now exploits B-stocks using small pool 2 instead of small pool 1. A long position is still the investment strategy, but this time the holding period of a B-stock now depends on its

T-day. Regarding return estimation and assignment of probability weights, historical returns are still used as the estimate for future performances, and these estimates are assigned weights based on SP/A theory. The

PBs of B-stocks are now considered for screening further the investment pool (small pool 2) to ensure a

efficient portfolio. A

efficient portfolio only considers a B-stock in the portfolio if and only if its

is at least higher than the minimum probability (set by the investor) at a given

T-day. As for the selection model, a modified scenario-based safety-first model was applied to generate the optimal portfolios. Now, the model’s objective is to have the highest cumulative return over the respective

T-days of each B-stock considered in the portfolio. Back-test results show that the proposed behavioral stock portfolio selection framework can also outperform benchmarks (e.g mean-variance portfolio) and the market. The first two studies consider a long position as the investment strategy, so the question is, can B-stocks be profitable using a short position investment strategy?

The succeeding study [

37] on behavioral stocks answers the question of whether a short position investment strategy can be applied to B-stocks. The study considered two irrational behaviors, which are over-reaction and disposition effect. The authors considered investment pool 2 and the short position (short-wait-buy-back) investment strategy. To make a profit in a short position investment, the shorted asset or stock should decrease in price such that you take profit when you buy back the asset. Therefore, the considered B-stocks should have the expected effect of negative returns so that when shorted, they will provide profit to the investor. These B-stocks are coined as short-sell B-stocks to differentiate from B-stocks whose expected effect are positive returns. Regarding return estimation and assignment of probability weights, historical returns are still considered as the return estimate for future performance and assumed to be equally likely. In terms of the portfolio selection model, a modified scenario-based safety-first model was applied to obtain the optimal portfolios. They modified the objective function to minimize the return rate of stock bought, which maximizes the profit for short-selling those same B-stocks. The resulting portfolios from the back-test show that they can also outperform the market. At this point, studies on B-stocks only considered the paper returns of the portfolio, so how will the B-stocks perform in a more sensible investment wherein portfolio re-balancing and actual trading costs are considered?

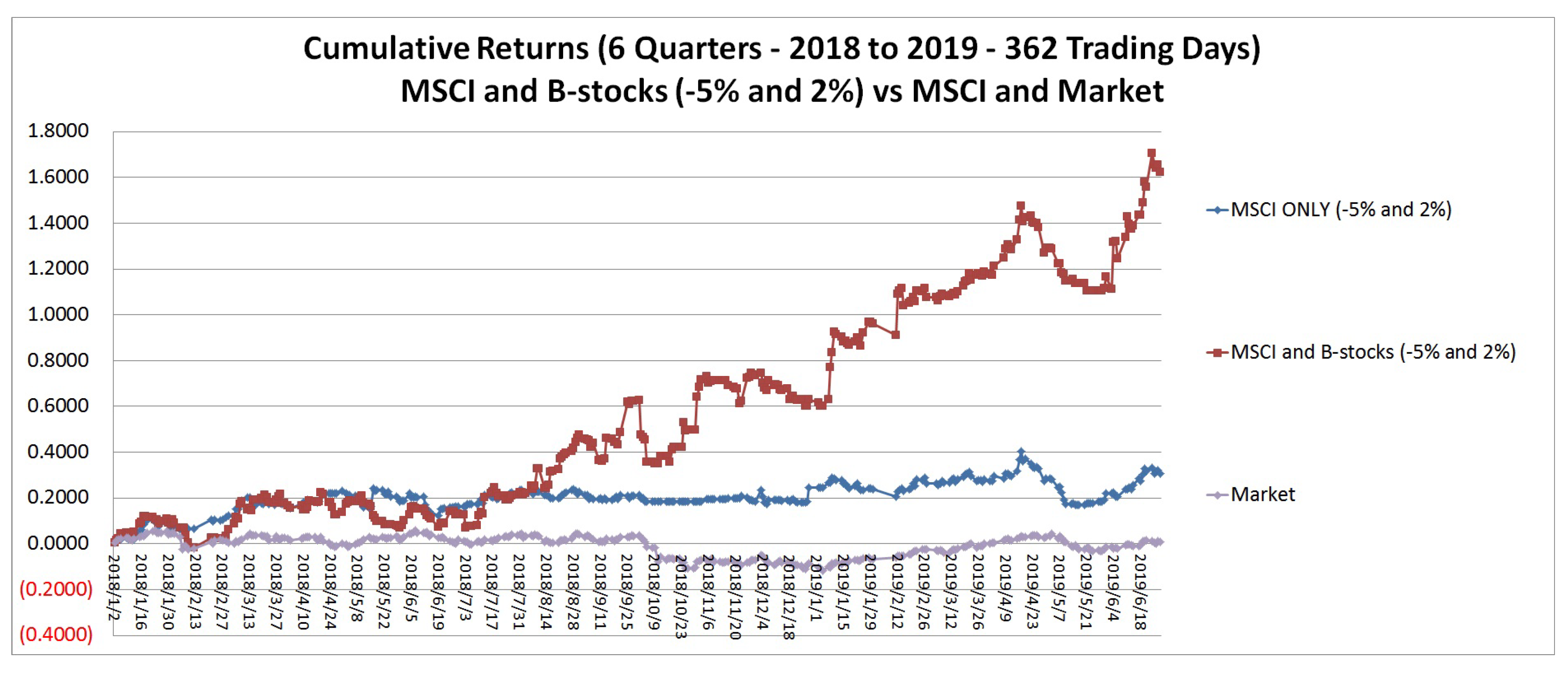

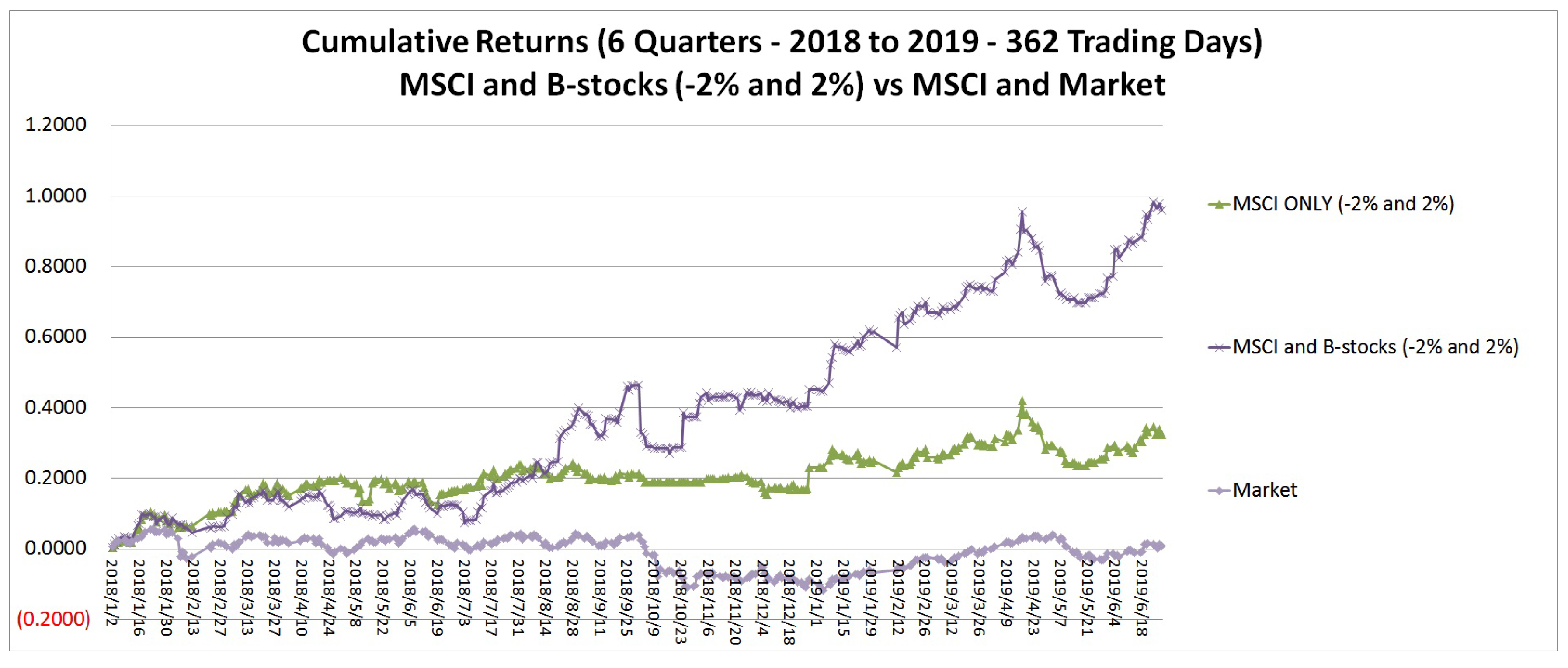

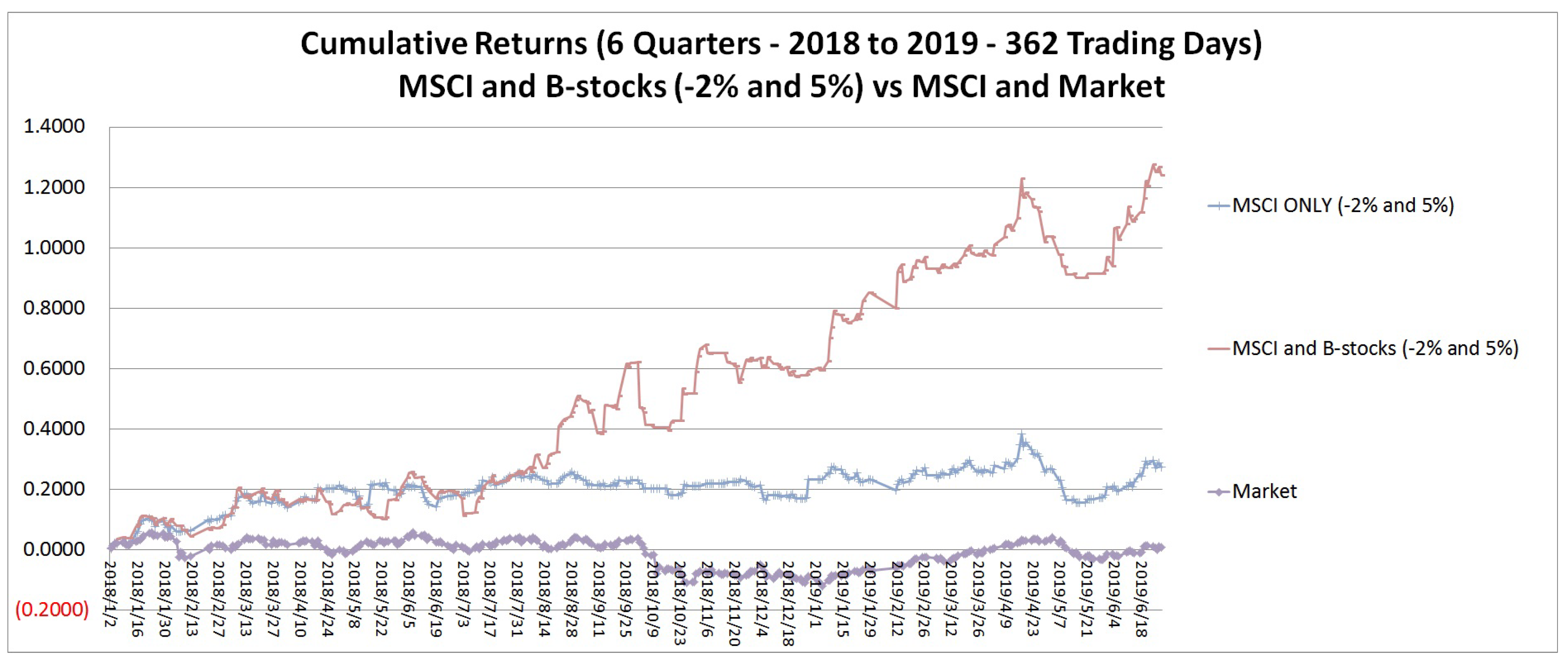

To make B-stocks a more realistic venture and utilizing small pool 2, ref. [

38] presented an aggregate portfolio selection model that considers both a long position and short position investment strategy on B-stocks & short-sell B-stocks while also considering actual trading costs. The aggregate model is a portfolio re-balancing model based on the scenario-based safety-first portfolio selection model. Still, the objective function is now modified to cater to the maximization of the returns of the buy & sell of B-stocks and short & close of short-sell B-stocks. Since each B-stocks have different

T-days, the resulting portfolio returns would not fall on a consistent time interval. It would be difficult to compare them to benchmark portfolios. Hence they provided a solution on how to compare the portfolio performances. Appropriately, the resulting portfolios also show that the portfolios with B-stocks and/or short-sell B-stocks can outperform traditional benchmarks even on actual trading conditions. The study still used over-reaction and disposition effect B-stocks in the back-test. Return scenarios were still estimated using historical returns, and the corresponding probabilities of each scenario were assigned using SP/A theory. The last 3 studies [

36,

37,

38] work on exploiting B-stocks in small pool 2, so what is next for B-stocks in small pool 1 as utilized by [

35]?

Another way of exploiting over-reaction and disposition effect B-stocks in small pool 1 was done by [

39], which improves upon the initial work of [

35]. They polished the proposed two-dimensional weightings and embedded it on a modified safety-first portfolio selection model wherein the portfolio chosen will satisfy not only the return scenarios but also the respective likelihood-to-effect or

PBs of each B-stock considered. They also considered the different risk attitudes of investors and changed the scenarios’ respective weights through SP/A theory to represent all types of investors during the back-test. Their work provides evidence that these B-stocks can be exploited to generate superior portfolios which can outperform benchmarks and possibly be a viable alternative investment option for investors. In terms of return estimation, the study, similar to the previous 4 studies [

35,

36,

37,

38] on B-stocks, only considered historical returns as an estimate for future performances. Thus, the question now is, “What if we can estimate also estimate the returns on the

Tth day?”.

This study addresses the question if we can improve the studies on B-stocks by actually estimating the returns of B-stocks on its Tth day. The current work proposes a behavioral stock portfolio selection framework wherein the respective T-day returns of B-stocks are estimated through regression analysis. For each B-stock, we empirically establish regression functions for the return on the effect day through the market’s and its past days return. By relating all the B-stocks to the market, we can correlate them. Based on the corresponding system of regression functions, we can have the return scenarios for the next period (e.g., tomorrow) by fitting in available information about the returns of the B-stock over the days observed during the test period (e.g., today). Thus, generating the realizations of the market and individual B-stock returns. This study also expands the types of behavioral stocks wherein disposition effect, over-reaction, under-reaction, ostrich effect, and herding B-stocks are now considered in generating a superior portfolio.

This paper is presented as follows.

Section 1 discusses the intro and related literature on modern portfolio theory, behavioral portfolio theory, the framework of behavioral portfolio optimization, irrational behaviors, and behavioral stocks & related studies.

Section 2 defines the proposed operational definitions, how scenarios are generated, and the portfolio selection model.

Section 3 provides an analysis of portfolio performances.

Section 4 states the concluding remarks of the work. Acknowledgment gives credit to the funding body that supported the study. Lastly, the

Appendix A include relevant attachments for the study.