Autonomy-Supportive and Controlling Teaching in the Classroom: A Video-Based Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Autonomous Versus Controlled Motivation

1.2. Autonomy Support

1.3. Controlling Teaching

1.4. Advantages of Qualitative Video-Based Observations

2. Research Questions

- (1)

- How does autonomy-supportive and controlling teaching develop during a lesson?

- (2)

- What are the categories of teachers’ autonomy-supportive and controlling behaviors?

- (3)

- What do teachers say and do to employ autonomy-supportive and controlling teaching?

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Procedure

3.3. Coding Protocol

- Codes were only applied to teachers, not to students. A code started and ended with a teacher’s utterances (verbal). Teachers’ tones and gestures (nonverbal) were interpreted to confirm meanings of utterances, but were not coded independently of utterances. Teachers’ verbal and nonverbal expressions were also interpreted based on their contexts. For example, what students said or did before or after was taken into consideration in understanding teachers’ verbal and nonverbal expressions.

- A code could be in more than one coding category. If the meanings of teachers’ utterances in a code involved more than one category of autonomy-supportive or/and controlling behaviors, this code could be in multiple coding categories at the same time.

- When coding controlling or non-controlling language, it was not sufficient to code an utterance as controlling or non-controlling only by finding the symbol word, such as “have to” or “can”, since the interpretation of a word is also based on context. For example, when a teacher is making suggestions, “have to” may not be intentional use of controlling language, but rather, just an ill-chosen word; it is only when obviously giving an official order to students and using “have to” that she is using controlling language.

4. Findings

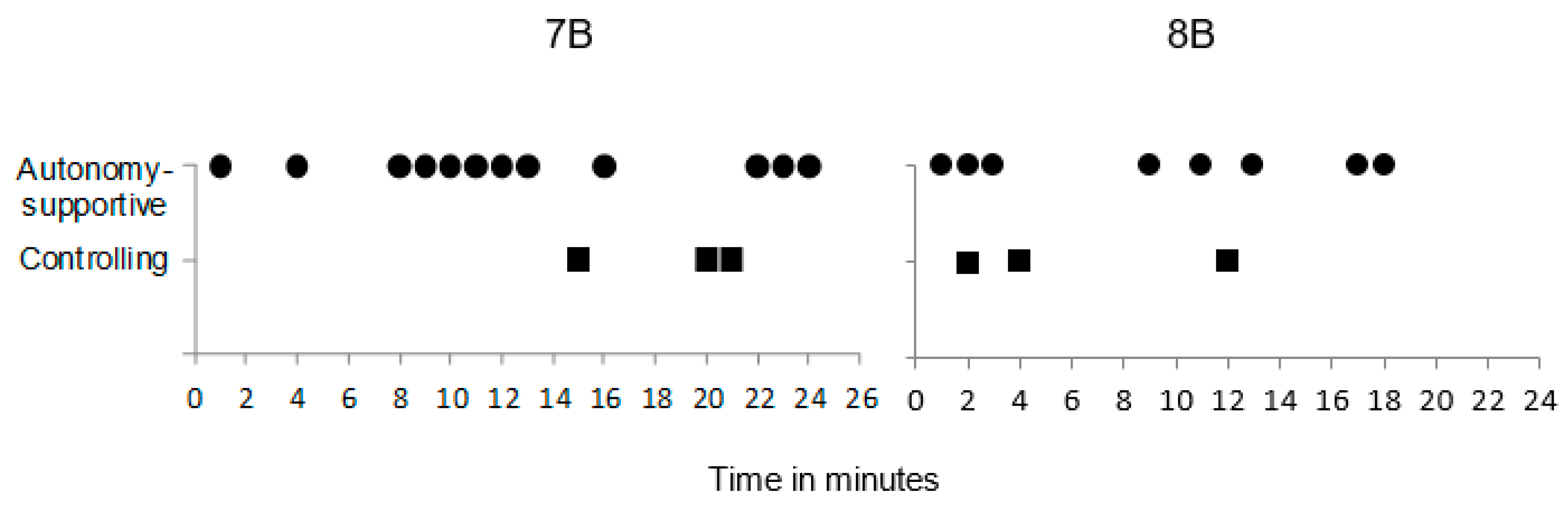

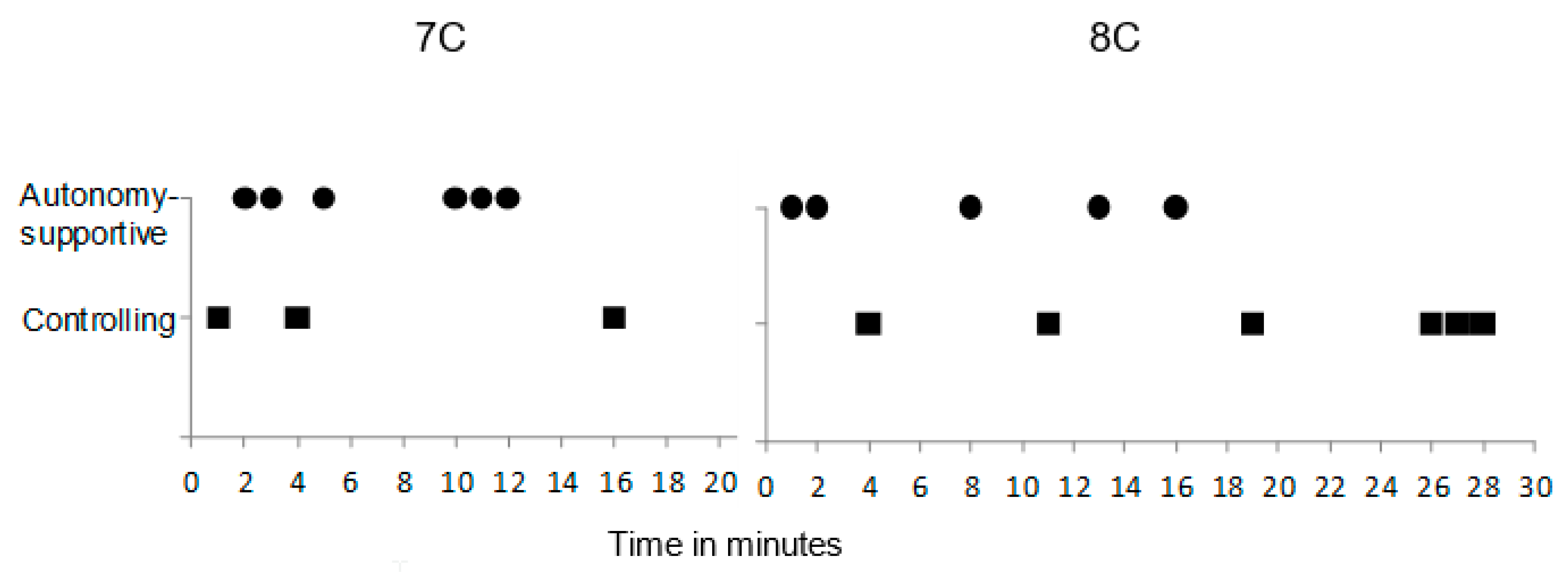

4.1. How Autonomy-Supportive and Controlling Teaching Develops during a Lesson

4.2. Categories of Teachers’ Autonomy-Supportive and Controlling Behaviors

4.3. Illustrations of Autonomy-Supportive and Controlling Teaching

4.3.1. Episodes from Anne’s Lessons

- Anne:

- So, I’m just silent for a moment…And you are too…And at that time you are silent and can close your eyes or put your hands there and try to get them all there and remember how many they are.

- Student:

- I don’t see any point doing this.

- Anne:

- This was the most difficult one. That’s why we asked it like this. And I asked this like this because if I had just said “read them”, I think that you wouldn’t have read the types. Or how is it if I said “just read them independently”? Would you have learned them independently by heart?

- Student:

- Maybe not by heart, but I would have read them.

- Anne:

- This is not so serious anyhow if something is left out…The last one was more like hair-splitting, so just forget it if you did not understand anything, it doesn’t matter…It doesn’t matter if you make a mistake because we are still practicing.

- Student:

- And on the other page, I’ve done them all from there.

- Anne:

- Oh no, it can’t be, but they are all here! (with a kind tone)

- Student:

- I didn’t understand there were also other exercises that you had to search for.

- Anne:

- That’s true, I admit. Okay, but it doesn’t matter if you have done them. What did you find from there then?

- Anne:

- Now everybody should raise their hand. To which group does “muutama” [a few] belong?…There’s still someone’s hand down…Wonderful! We should have a photo of this.

- Anne:

- I think this would be a great opportunity to finish this (reading their writing about an author and clarifying the points they got) if you even care a bit about your grade.

- Student:

- The Silmarillion remained unfinished upon his death in 1973, when he was 21 years old.

- Anne:

- Twenty-one? Did you say so? Did I hear wrong? (with a calm tone)

- Student:

- Oh no, eighty-one.

- Anne:

- I was thinking indeed that he lived a bit longer. All right! (with an encouraging tone)

- Anne:

- You mark down how much you would get for your answer. Would I get eight, or would I get three, or what would I add yet to make it a proper essay?...I put it this way: How many got more than five points? How many got more than eight points? More than ten?

- Anne:

- The next brave individual…Tomi would be brave, but he hasn’t done it. You have not done your homework…You have been sitting there and have been doing nothing and haven’t done your homework. That doesn’t mean that you can stay there slacking.

- Student:

- Yeah but, I’m processing these things.

- Anne:

- No, you have been processing these far too much. You have been processing since yesterday. Haven’t you started at all doing it?

- Student:

- I have to…but….

4.3.2. Episodes from Laura’s Lessons

- Laura:

- So, there are plenty of words to describe schools. Even though you know all the schools perfectly, still, when you go to Spain, you have to explain again what school you are in, what kind of school it is, your grade, how old you are, and what has happened there. That’s just because school systems are different in every country. Those small words help you.

- Laura:

- Your problem is that you watch a lot of American programs, I claim. But we are in Europe and Great Britain is closer to us, and that’s why we should use British words.

- Laura:

- An interactive whiteboard is like the “esiäiti” of a touchscreen.

- Student:

- Esiäiti, haha!

- Laura:

- That word doesn’t exist…What is it? How is it called?...This is its “esiäiti.” It’s evolved from….

- Student:

- Now I know.

- Laura:

- Hey, Lisa, have you done it? Concentrate on your role.

- Laura:

- Choose a bit what you are going to do. Work with your iPads…Either you do those Sanoma Pro exercises…or then you can go to Quizlet…. So, go either to the site Sanomapro.fi or… That is now this Sanoma Pro…and the other one is Quizlet…Yes, you can choose from all the exercises, they are a bit different there… Even though there are terribly many, check which ones are beneficial to you.

- Laura:

- And then we will do something fun during the class next week. Is there something you would like to do?

- Student:

- So, we should all have the right to go to the toilet during class.

- Laura:

- If you empty your pockets, you may go to the toilet during class.

- Laura:

- Your hairdresser would have worked for nothing if you had your hood over your head.

- Laura:

- You have five minutes left, actually four. Use them well.

- Student:

- Three.

- Laura:

- Shh...my clock wins.

- Student:

- No, it doesn’t.

- Laura:

- Janne, do exercises. Hey, Sampo, Tomi, and Pasi…Mmm, Janne, Kimmo, some action…Er, Janne…Eerikki…Discuss it in English…Eerikki, you concentrate on your own work…Janne, the same goes for you…Don’t pack your stuff yet. (with an annoyed tone)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Overview of self-determination theory: An organismic dialectical perspective. In Handbook of Self-Determination Research; Deci, E.L., Ryan, R.M., Eds.; University of Rochester Press: Rochester, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Assor, A.; Kaplan, H.; Roth, G. Choice is good, but relevance is excellent: Autonomy-enhancing and suppressing teaching behaviors predicting students’ engagement in schoolwork. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 27, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J. Why teachers adopt a controlling motivating style toward students and how they can become more autonomy supportive. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 44, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.; Jang, H.; Carrell, D.; Jeon, S.; Barch, J. Enhancing high school students’ engagement by increasing their teachers’ autonomy support. Motiv. Emot. 2004, 28, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assor, A.; Kaplan, H.; Kanat-Maymon, Y.; Roth, G. Directly controlling teacher behaviors as predictors of poor motivation and engagement in girls and boys: The role of anger and anxiety. Learn. Instr. 2005, 15, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Assor, A.; Ahmad, I.; Cheon, S.H.; Jang, H.; Kaplan, H.; Moss, J.D.; Olaussen, B.S.; Wang, C.J. The beliefs that underlie autonomy-supportive and controlling teaching: A multinational investigation. Motiv. Emot. 2014, 38, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Simons, J.; Lens, W.; Soenens, B.; Matos, L. Examining the motivational impact of intrinsic versus extrinsic goal framing and autonomy-supportive versus internally controlling communication style on early adolescents’ academic achievement. Child Dev. 2005, 76, 483–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzisarantis, N.L.; Hagger, M.S. Effects of an intervention based on self-determination theory on self-reported leisure-time physical activity participation. Psychol. Health 2009, 24, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheon, S.H.; Reeve, J. Do the benefits from autonomy-supportive training program endure? A one-year follow-up investigation. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2013, 14, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, S.H.; Reeve, J. A classroom-based intervention to help teachers decrease students’ amotivation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 40, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, S.H.; Reeve, J.; Moon, I.S. Experimentally based, longitudinally designed, teacher-focused intervention to help physical education teachers be more autonomy supportive toward their students. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2012, 34, 365–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tessier, D.; Sarrazin, P.; Ntoumanis, N. The effects of an experimental programme to support students’ autonomy on the overt behaviours of physical education teachers. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2008, 23, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assor, A.; Roth, G.; Deci, E.L. The emotional costs of parents’ conditional regard: A self-determination theory analysis. J. Personal. 2004, 72, 47–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtak, E.M.; Kunter, M. Effects of autonomy-supportive teaching on student learning and motivation. J. Exp. Educ. 2012, 80, 284–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.; Tseng, C.-M. Cortisol reactivity to a teacher’s motivating style: The biology of being controlled versus supporting autonomy. Motiv. Emot. 2011, 35, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.; Bolt, E.; Cai, Y. Autonomy-supportive teachers: How they teach and motivate students. J. Educ. Psychol. 1999, 91, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Reeve, J.; Deci, E.L. Engaging students in learning activities: It is not autonomy support or structure but autonomy support and structure. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 102, 588–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haerens, L.; Aelterman, N.; Van den Berghe, L.; De Meyer, J.; Soenens, B.; Vansteenkiste, M. Observing physical education teachers’ need-supportive interactions in classroom settings. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2013, 35, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Berghe, L.; Soenens, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Aelterman, N.; Cardon, G.; Tallir, I.B.; Haerens, L. Observed need-supportive and need-thwarting teaching behavior in physical education: Do teachers’ motivational orientations matter? Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2013, 14, 650–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, H.M.; Nielsen, B.L. Video-based analyses of motivation and interaction in science classrooms. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2013, 35, 906–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupers, E.; van Dijk, M.; van Geert, P. Changing patterns of scaffolding and autonomy during individual music lessons: A mixed methods approach. J. Learn. Sci. 2017, 26, 131–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntoumanis, N. A prospective study of participation in optional school physical education using a self-determination theory framework. J. Educ. Psychol. 2005, 97, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Deci, E.L. Competitively contingent rewards and intrinsic motivation: Can losers remain motivated? Motiv. Emot. 2003, 27, 273–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, K.J.; Ntoumanis, N.; Ryan, R.; Bosch, J.A.; Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C. Self-determination theory and diminished functioning: The role of interpersonal control and psychological need thwarting. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 37, 1459–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soenens, B.; Sierens, E.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Dochy, F.; Goossens, L. Psychologically controlling teaching: Examining outcomes, antecedents, and mediators. J. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 104, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.; Nix, G.; Hamm, D. The experience of self-determination in intrinsic motivation and the conundrum of choice. J. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 95, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Eghrari, H.; Patrick, B.C.; Leone, D. Facilitating internalization: The self-determination theory perspective. J. Personal. 1994, 62, 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.C.; Cox, E.M.; Kouides, R.; Deci, E.L. Presenting the facts about smoking to adolescents: The effects of an autonomy supportive style. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 1999, 153, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.; Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory: A dialectical framework for understanding the sociocultural influences on student motivation. In Research on Sociocultural Influences on Motivation and Learning: Big Theories Revisited; McInerney, D., Van Etten, S., Eds.; Information Age Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 2004; pp. 31–59. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.-L.; Reeve, J. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of intervention programs designed to support autonomy. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 23, 159–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H. Supporting students’ motivation, engagement, and learning during an uninteresting activity. J. Educ. Psychol. 2008, 100, 798–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.; Jang, H.; Hardré, P.; Omura, M. Providing a rationale in an autonomy-supportive way as a strategy to motivate others during an uninteresting activity. Motiv. Emot. 2002, 26, 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.; Jang, H. What teachers say and do to support students’ autonomy during a learning activity. J. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 98, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Simons, J.; Lens, W.; Sheldon, K.M.; Deci, E.L. Motivating learning, performance, and persistence: The synergistic role of intrinsic goals and autonomy-support. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 87, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanou, C.R.; Perencevich, K.C.; DiCintio, M.; Turner, J.C. Supporting autonomy in the classroom: Ways teachers encourage student decision making and ownership. Educ. Psychol. 2004, 39, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naceur, A.; Schiefele, U. Motivation and learning—The role of interest in construction of representation of text and long-term retention: Inter- and intra-individual analyses. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2005, 20, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiefele, U. Interest, learning, and motivation. Educ. Psychol. 1991, 26, 299–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiefele, U. Interests and learning. In Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning; Seel, N.M., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1623–1626. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The support of autonomy and the control of behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 1024–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M.; Williams, G.C. Need satisfaction and the self-regulation of learning. Learn. Individ. Differ. 1996, 8, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grolnick, W.S.; Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Internalization within the family: The self-determination theory perspective. In Parenting and Children’s Internalization of Values; Grusec, J.E., Kuczynski, L., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 135–161. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and the “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meyer, J.; Soenens, B.; Aelterman, N.; Haerens, L. The different faces of controlling teaching: Implications of a distinction between externally and internally controlling teaching for students’ motivation in physical education. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2016, 21, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meyer, J.; Tallir, I.B.; Soenens, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Aelterman, N.; Van den Berghe, L.; Speleers, L.; Haerens, L. Does observed controlling teaching behavior relate to students’ motivation in physical education? J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 106, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, H. Teachers’ autonomy support, autonomy suppression and conditional negative regard as predictors of optimal learning experience among high-achieving Bedouin students. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2018, 21, 223–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosston, M.; Ashworth, S. Teaching Physical Education, 5th ed.; Benjamin Cummins: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- ELAN (Version 5.0.0-Beta) [Computer Software]. Nijmegen: Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics. Available online: https://tla.mpi.nl/tools/tla-tools/elan/ (accessed on 18 April 2017).

- Tulis, M. Error management behavior in classrooms: Teachers’ responses to student mistakes. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2013, 33, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, J.F.; Snyder, T.L.; Rogers, D.T.; Collins, C.L. Permissive, authoritarian, and authoritative instructors: Applying the concept of parenting styles to the college classroom. Individ. Differ. Res. 2013, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Steuer, G.; Rosentritt-Brunn, G.; Dresel, M. Dealing with errors in mathematics classrooms: Structure and relevance of perceived error climate. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 38, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R.M. On psychological growth and vulnerability: Basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. J. Psychother. Integr. 2013, 23, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, K.J.; Ntoumanis, N.; Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C. A review of controlling motivational strategies from a self-determination theory perspective: Implications for sports coaches. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2009, 2, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J. Teachers as facilitators: What autonomy-supportive teachers do and why their students benefit. Elem. Sch. J. 2006, 106, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmivuori, M. Affect and self-regulation. Educ. Stud. Math. 2006, 63, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education. All Our Futures: Creativity, Culture and Education; Department for Education and Employment: London, UK, 1999.

- Jónsdóttir, S.R. Narratives of creativity: How eight teachers on four school levels integrate creativity into teaching and learning. Think. Skills Creat. 2017, 24, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, D.; Jindal-Snape, D.; Digby, R.; Howe, A.; Collier, C.; Hay, P. The roles and development needs of teachers to promote creativity: A systematic review of literature. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2014, 41, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, B.K. Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Dev. 1996, 67, 3296–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soenens, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Luyten, P.; Duriez, B.; Goossens, L. Maladaptive perfectionistic self-representations: The mediational link between psychological control and adjustment. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2005, 38, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C.; Nolen, S.B. Introduction: The relevance of the situative perspective in educational psychology. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 50, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Teacher | Gender | Subject | Teaching Years | Grade/Class | Homeroom Teacher (Yes/No) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anne | Female | Finnish | 30 | 7B & 8B | No |

| Laura | Female | English | 5 | 7C & 8C | Yes (8C) |

| Categories | Teachers’ Specific Behaviors |

|---|---|

| Providing explanatory rationales | Verbal explanations that help students understand why self-regulation of a learning activity has personal utility [4,29,33,34]. |

| Acknowledging negative affect | Accepting, or even welcoming, student criticisms or expressions of negative affect (e.g., “this is boring”) that might conflict with teachers’ expectations [4,5,19,35]. |

| Using non-controlling language | Communications that minimize pressure (absence of “should”, “must”, “got to”, and “have to”) and convey a sense of choice and flexibility with the use of, e.g., “can”, “could”, or “may” [19,29,36]. |

| Offering choices | Providing students with options, respecting their preferences, encouraging their self-paced learning and self-evaluation [4,5,28,37]. |

| Fostering interest in learning | Promoting students’ feelings of enjoyment, sense of challenge, and curiosity during engagement in an activity [5,31,39,40]. |

| Praise as informational feedback | Showing appreciation for students’ effort, persistence, opinions, improvement, or performance [19,35,41]. |

| Categories | Teachers’ Specific Behaviors |

|---|---|

| Relying on outer sources | Giving deadlines, rewards, or threats of punishments to motivate students to engage in an activity [5,25,42,45]. |

| Rejecting negative affect | Responding to students’ complaints, criticisms, or expressions of negative affect about a learning activity with authoritarian power assertions [4,5,7]. |

| Using controlling language | Pressuring students into compliance with words like “should”, “have to”, “must”, or “got to”, using directives or commands, and neglecting explanatory rationales for expected behaviors [5,7,35,45]. |

| Creating ego involvement | Pressuring students to act by creating internal compulsions or feelings of guilt, shame, and anxiety, e.g., guilt induction, shaming, and public criticisms [9,42,45,46]. |

| Conditional regard | Providing attention, affection, or support only if particular behaviors are displayed, or threatening to withdraw such attention, affection, or support when specified behaviors are not displayed [15,27,47]. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, J.; Vauras, M.; Volet, S.; Salo, A.-E.; Kajamies, A. Autonomy-Supportive and Controlling Teaching in the Classroom: A Video-Based Case Study. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9030229

Jiang J, Vauras M, Volet S, Salo A-E, Kajamies A. Autonomy-Supportive and Controlling Teaching in the Classroom: A Video-Based Case Study. Education Sciences. 2019; 9(3):229. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9030229

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Jingwen, Marja Vauras, Simone Volet, Anne-Elina Salo, and Anu Kajamies. 2019. "Autonomy-Supportive and Controlling Teaching in the Classroom: A Video-Based Case Study" Education Sciences 9, no. 3: 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9030229

APA StyleJiang, J., Vauras, M., Volet, S., Salo, A.-E., & Kajamies, A. (2019). Autonomy-Supportive and Controlling Teaching in the Classroom: A Video-Based Case Study. Education Sciences, 9(3), 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9030229