Understanding Identity and Context in the Development of Gay Teacher Identity: Perceptions and Realities in Teacher Education and Teaching

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

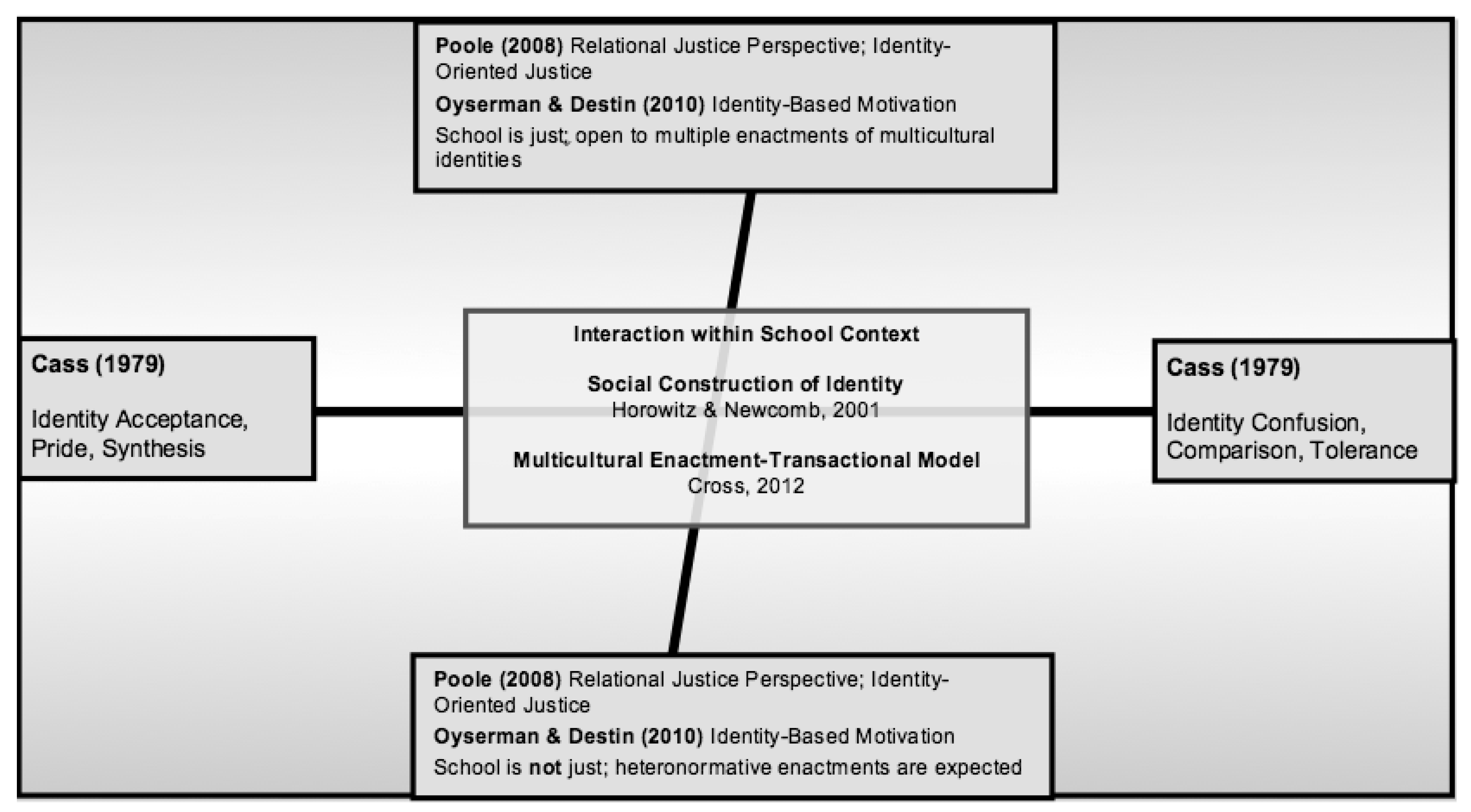

3. Conceptual Framework

3.1. Conceptual Framework: The School Context

3.2. Conceptual Framework: The Gay Teacher

4. Literature Review

4.1. Racial Identity Development

4.1.1. Nigrescence

While the first phase involves immersion into a total Black frame of reference, the second phase (emersion) represents emergence from the dead-end, racist, oversimplified aspects of Immersion. … the person’s emotions level off, and psychological defensiveness is replaced by affective and cognitive openness, allowing the person to be more critical in his or her analysis.[23] (p. 158)

4.1.2. Black Identity Development Model

4.2. Gay Identity Development

Gay Identity through a Social Constructionist Perspective

4.3. Teacher Identity as Identity Performance

is the very stuff of teaching, the landscape within which we live as teachers and researchers, and within which the work of teachers can be seen as making sense. This is not merely a claim about the aesthetic or emotional sense of the notion of story with our intuitive understanding of teaching, but an epistemological claim that teachers’ knowledge in its own terms is ordered by story and can best be understood in this way. (p. 3)

5. Methodology

6. Peter Ryan

Participant Profile

Yeah, when I first moved, I got teased a lot because I was the new kid and was teased a lot about my accent, being from New York, and the way I spoke. As I got older, I got teased by the boys because I was terrible at sports and didn’t like sports, I didn’t do what all the other boys were doing. I was called a sissy and never felt like I fit in except for a small group of friends that I had.

I pretty quickly associated the feelings with ‘being gay’—In middle school kids talked about “gay” teachers all the time, mostly to poke fun at them. Beyond the fact that being gay meant boys liking other boys, and that kids made fun of people who were gay, I didn’t understand much more about homosexuality the time.

I had just found out what it was like to lose a friendship over my sexual identity. It could have made me more fearful of it occurring again in the future, but it had the opposite effect. If I could go through it once and still feel strong—emotionally unbroken—then surely, I could handle telling more people.

‘I found some pictures of men on the computer. Are you gay?’ I remember my heart just about pounding out of my chest and trying to play it off like I had no clue what he was talking about. He wouldn’t let off though, ‘so then you must be bi?’ I eventually snapped at him, flat out denying I was gay and telling him never to bring it up again. So, he didn’t. We didn’t talk about it again for 5 years, when I was ready to talk about it.

I told her the truth. That I was in a relationship for 3 years that just ended and that the only reason I didn’t tell her was because I was gay. She hugged me and told me that relationships are hard—not even mentioning the fact that I was gay. She asked me what happened and about who it was with. She was so remarkably supportive.

Working for the DA’s office was a disenchanting experience for someone who has grown up with Hollywood’s glorification of the legal world. I observed lawyers spending countless hours with deskwork—writing briefs, etc. It wasn’t the type of work I had initially imagined.

We spent that trip in DC lobbying congressmen and senators from [our state’s] delegation to vote on some key pieces of legislation to increase student aid funding. Most of the bills didn’t pass—which could have been disheartening, but I think truly lit a spark.

7. Peter’s Case as Emblematic, Peter’s Story as Inspirational

8. Recommendations for Teacher Educators

9. Recommendations for Educational Leaders

10. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haddad, Z. A Multiple Case Study of Gay Teacher Identity Development: Negotiating and Enacting Identity to Interrupt Heteronormativity. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wittig, M. The Straight Mind; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, M. (Ed.) Fear of a Queer Planet: Queer Politics and Social Theory; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, M. The Trouble with Normal: Sex, Politics, and the Ethics of Queer Life; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Illich, I. Deschooling Society; Marian Boyars: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran-Smith, M.; Shakman, K.; Jong, C.; Terrell, D.; Barnatt, J.; Mcquillan, P. Good and just teaching: The case for social justice in teacher education. Am. J. Educ. 2009, 115, 347–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, W.E., Jr. The enactment of race and other social identities during everyday transactions. In New Perspectives on Racial Identity Development: A Theoretical and Practical Anthology, 2nd ed.; Wijeyesinghe, C., Jackson, B., Eds.; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 192–215. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman, D.; Destin, M. Identity-based motivation: Implications for intervention. Couns. Psychol. 2010, 38, 1001–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peshkin, A. In search of subjectivity—One’s own. Educ. Res. 1988, 17, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- DeJean, W. Out gay and lesbian K-12 educators: A study in radical honesty. J. Gay Lesbian Issues Educ. 2007, 4, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J. Removing the masks: Considerations by gay and lesbian teachers when negotiating the closet door. J. Poverty 2006, 10, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudoe, N. Lesbian teachers’ identity, power and the public/private boundary. Sex Educ. 2010, 10, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J. Teacher education and the development of professional identity: Learning to be a teacher. In Connecting Policy and Practice: Challenges for Teaching and Learning in Schools and Universities; Denicolo, P., Kompf, M., Eds.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, S.; Busse, W.J. The gay identity questionnaire: A brief measure of homosexual identity formation. J. Homosex. 1994, 26, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cass, V.C. Homosexual identity formation: A theoretical model. J. Homosex. 1979, 4, 219–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S.; Gallois, C. Gay and lesbian identity development: A social identity perspective. J. Homosex. 1996, 30, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, J.L.; Newcomb, M.D. A multidimensional approach to homosexual identity. J. Homosex. 2001, 42, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, W.E., Jr.; Smith, L.; Payne, Y. Black identity: A repertoire of daily enactments. In Counseling across Cultures, 15th ed.; Pedersen, P.B., Draguns, J.G., Lonner, W.J., Trimble, J.E., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 9–107. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, E.H. Identity, Youth and Crisis; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Mead, G. Mind, Self and Society; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, J.P. Identity as an analytic lens for research in education. Rev. Res. Educ. 2001, 25, 99–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, W.E. The Negro-to-Black conversion experience: Towards a psychology of Black liberation. Black World. 1971, 20, 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, W.E., Jr. Shades of Black: Diversity in African-American Identity; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, W.E., Jr.; Fhagen-Smith, P. Patterns of African American identity development: A life span perspective. In New Perspectives on Racial Identity Development: A Theoretical and Practical Anthology; Wijeyesinghe, C., Jackson, B., Eds.; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 243–270. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, B.W. Black identity development: Further analysis and elaboration. In New Perspectives on Racial Identity Development: A Theoretical and Practical Anthology; Wijeyesinghe, C., Jackson, B.W., Eds.; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 8–31. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, E. Developmental stages of the coming out process. J. Homosex. 1982, 7, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hencken, J.D.; O’Dowd, W.T. Coming out as an aspect of identity formation. Gai Saber 1976, 1, 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.A. Going public: A study in the sociology of homosexual liberation. J. Homosex. 1977, 3, 49–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, H.P. The coming-out process for homosexuals. Hosp. Community Psychiatry 1991, 42, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, H.L.; McDonald, G.J. Homosexual identity as a developmental process. J. Homosex. 1984, 9, 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Troiden, R. The formation of homosexual identities. J. Homosex. 1989, 17, 43–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, H. A further exploration of the lesbian identity development and its measurement. J. Homosex. 1997, 34, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, K. The place of story in the study of teaching and teacher education. Educ. Res. 1993, 22, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran-Smith, M.; Lytle, S. Relationships of knowledge and practice: Teacher learning in communities. Rev. Res. Educ. 1999, 24, 249–307. [Google Scholar]

- Elbaz, F. The teacher’s practical knowledge: Report of a case study. Curric. Inq. 1991, 11, 43–71. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, F.M.; Clandinin, D.J. Stories of experience and narrative inquiry. Educ. Res. 1990, 19, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinney, J.S. The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. J. Adolesc. Res. 1992, 7, 156–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, W. Intersections of organizational justice and identity under the new policy direction: Important understandings for educational leaders. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2008, 11, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, D.; Johnson, R. Schooling Sexualities; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, M. Becoming Subjects: Sexuality and Secondary Schooling; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Blount, J. Fit to Teach: Same-Sex Desire, Gender, and School Work in the Twentieth Century; State University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Szalacha, L. Educating teachers on LGBTQ issues: A review of research and program evaluations. J. Gay Lesbian Issues Educ. 2004, 1, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann-Wilmarth, J.; Bills, P. Identity shifts: Queering teacher education research. Teach. Educ. 2010, 45, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, T. Addressing diversity in U.S. teacher preparation programs: A survey of elementary and secondary programs’ priorities and challenges from across the United States of America. Teaching and Teach. Educ. 2007, 23, 1258–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, K.; Ferfolja, T. “What are we doing for this?” Dealing with lesbian and gay issues in teacher education. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2001, 22, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, M.; Hoyt, M.; Slattery, P. Teaching gender and sexuality diversity in foundations of education courses in the U.S. Teach. Educ. 2009, 20, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorski, P.; Davis, S.; Reiter, A. An examination of the (in)visibility of sexual orientation, heterosexism, homophobia, and other LGBTQ concerns in U.S. multicultural teacher education coursework. J. LGBT Youth. 2013, 10, 224–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haddad, Z. Understanding Identity and Context in the Development of Gay Teacher Identity: Perceptions and Realities in Teacher Education and Teaching. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9020145

Haddad Z. Understanding Identity and Context in the Development of Gay Teacher Identity: Perceptions and Realities in Teacher Education and Teaching. Education Sciences. 2019; 9(2):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9020145

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaddad, Zaid. 2019. "Understanding Identity and Context in the Development of Gay Teacher Identity: Perceptions and Realities in Teacher Education and Teaching" Education Sciences 9, no. 2: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9020145

APA StyleHaddad, Z. (2019). Understanding Identity and Context in the Development of Gay Teacher Identity: Perceptions and Realities in Teacher Education and Teaching. Education Sciences, 9(2), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9020145