Abstract

The reproduction of white supremacist culture in schools continues to marginalize Students of Color in a variety of implicit and explicit ways. A diverse teacher workforce not only helps to disrupt the direct effects of racism on Students of Color, but also prepares all students for successful democratic participation in a diverse global society. This article uses a portion of qualitative interview data from undergraduate Preservice Teachers of Color from a dissertation study completed within a College of Education at a minority-serving public university in the southwestern United States. This study adds to the literature on the complex issues that have resulted in our nation’s teacher demographic diversity gap. The findings from these data reveal meaningful teacher–student encounters that eight successful Preservice Teachers of Color have experienced during their K12 education and how these experiences affected their drive to become a teacher. The findings confirm that resolving the teacher diversity gap is more than a simple recruitment problem. Practitioners, scholars, and policy-makers must attend to the climate and culture of schools, in particular the racialized experiences of Students of Color, if we hope to begin to address the complexity of this issue. All names and places are pseudonyms. Participants chose their pseudonym, and their identifying categories listed are directly from how they identified themselves during the interviews.

1. Introduction

A diverse teacher workforce benefits not only Students of Color through congruency in teacher–student relationships, but also prepares all students for successful democratic and economic participation in a diverse global society [1]. Public school Students of Color overall now make up slightly more than 50% of all school enrollment; yet, our teacher workforce is more than 80% white and female [2,3]. Putman, Hansen, Walsh, and Quintero [4] refer to this as “the teacher diversity gap.” Empirical research suggests that the lack of a diverse teacher workforce contributes to the achievement gap as well as other poor educational outcomes [5]. Scholars also point to this diversity gap when explaining why urban schools experience the highest rates of teacher attrition, which leads to a revolving door of inexperienced teachers serving a vulnerable and disenfranchised population [6,7,8]. Recent scholarship also indicates that Students of Color who have just one or more racially matched teacher in elementary school are more likely to attend college [9].

Even in the face of scholarship demonstrating the benefits of a diverse teacher workforce, little progress has been made that substantially addresses the complexities of the teacher diversity gap [4]. Neal, Sleeter, and Kumashiro [10] point out that responses to the teacher diversity gap fall into two categories. The first involves scholarship on preparing white female teachers to teach marginalized populations of students who are substantially unlike themselves using culturally relevant and responsive approaches [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. The second category is focused on the lack of People of Color choosing to become teachers. While there has been growing attention to this problem over the last five years, there is a noticeable gap in the literature exploring the explicit experiences of current Preservice Teachers of Color on their journey to become teachers through a critical lens that centers sociopolitical issues of racial/ethnic identity [20].

1.1. Study Origin and Purpose

The purpose of the study was to examine the experiences of Preservice Teachers of Color in order to shed more light on the complex issues that have resulted in the teacher diversity gap through centering the assets and experiences of those who are successfully navigating the teacher preparation pipeline. This dataset in this study is part of a larger mixed-methods study involving both teacher educators and Preservice Teachers of Color from the same College of Education (COE) within a public university identified as one of the most diverse higher education institutions in the United States. Findings from inductive coding of qualitative data from the eight undergraduate Preservice Teachers of Color in the larger study revealed a common theme of K12 experiences that were relevant to the preservice teachers’ decisions to go to college and to pursue teaching. This study examines those findings more explicitly to help explore and understand how these eight undergraduate Students of Color persisted through their K12 experiences and came to choose the pathway of teaching. The study also examines how the legacy of K12 experiences affected the ways in which they experienced and navigated their teacher education coursework. Specifically, themes related to K12 teaching and learning also emerged through how the participants described observations of inservice teachers during field experiences. The research question that framed the study was, How have previous K12 educational experiences of Preservice Teachers of Color affected their pathway to pursue teaching as a career?

This analysis is framed by the critical theory Culturally Relevant Critical Teacher Care (CRCTC) in order to bring into sharp relief the negative K12 experiences of these participants. The findings confirm that resolving the teacher diversity gap is more than a simple recruitment problem. Practitioners, scholars, and policy-makers must attend to the climate and culture of schools, in particular the racialized experiences of Students of Color, if we hope to begin to address the complexity of this issue.

1.2. Theoretical Framework: Culturally Relevant Critical Teacher Care

Culturally Relevant Critical Teacher Care (CRCTC) is a critical theoretical perspective on care in education that has emerged out of and in resistance to a colorblind theory of authentic care identified in some K12 settings [19,20,21,22]. It additionally was shaped through empirical studies of exceptional teaching by African-American teachers of African-American students [23,24,25]. First formally conceptualized by Roberts [21], CRCTC is rooted in the work of Ladson-Billings [26,27]. The framework elements have since been utilized in practice and research and further refined by critical scholar-practitioners in more recent years [19,28,29,30].

Culturally Relevant Critical Teacher Care reframes the notion of teacher–student care using a critical stance that centers the sociocultural experiences of students [19,21,30,31]. It problematizes traditional notions of teacher–student care by asking who is doing the caring and how is it situated within the specific needs and experiences of those being “cared for” [32]. Hambacher and Bondy’s [28] recent review of studies used to refine CRCTC identified that the following aspects of exceptional teaching by African-American teachers of African-American students produced positive students outcomes: “teachers insisted on high-quality performance, worked closely with families, allowed for no wasted instructional time, consistently communicated their belief in their students’ capacity, and, perhaps most importantly, assumed responsibility for their students’ success” (p. 328).

Hambacher and Bondy [28] identify three key ideological tenets of CRCTC that are necessary for it to be enacted by educators: asset-based thinking, political clarity, and critical hope. Asset-based thinking draws together the work of several critical scholars through the recognition of the intellectual, cultural, and socioemotional strengths of marginalized students. This includes Moll, Amanti, Neff, and Gonzalez’s [33] work on funds of knowledge, Yosso’s [34] work on cultural capital, and is also supported by other empirical studies that suggest that teacher focus on assets over deficits results in positive student outcomes [29,35,36].

Political clarity is rooted in Freirean [37,38] philosophy that recognizes the reproduction of social injustice in education and therefore calls educators to work not only as an academic facilitator but also as an advocate for social justice alongside students [28,37,39,40,41,42,43]. Critical hope is born out of the Freirean (2000) exigent call to change the world through social justice activism [28,41]. Duncan-Andrade [44] enacts this in his scholarship and praxis and shares that it is “an audacious hope” (p. 191) that does not turn away from the barriers and setbacks, but refuses to give up because it is inextricably linked to “a deep sense of responsibility for the collective well-being of humanity” [28] (p. 330). Hambacher and Bondy [28] identify that critical hope is the necessary fuel for Teacher Educators (TEs) who wish to practice CRCTC. This framework—born out of exceptional African-American teacher praxis—is therefore ideal for critical scholarship examining how the educational experiences of preservice Teachers of Color influenced their pathways toward becoming a teacher. This framework is also particularly well-suited to this study because it speaks directly to the problem of the teacher diversity gap via a metaconstruct that unfolds across the spectrum of teaching and learning: K12 experiences of teaching and learning framed to influence future teachers who will themselves reproduce or resist cultural spheres of teaching in learning in K12 classrooms.

Much scholarship on public education in the U.S. reinforces the notion that schools are centers of social reproduction [45,46]: thus, how teachers experience care and support will likely affect the care they demonstrate for their future students. Given the reproductive nature of sociocultural influences, it seems not only useful, but vital to explore the nature of CRCTC in this context. To truly address the problem of the teacher diversity gap, Students of Color who are pursuing teaching need to not only stay in college and become teachers, but also must develop the skills and dispositions needed for effective practice in order to remain in the profession. Taking the cycle of teaching, learning, and social reproduction one step further, we might also consider how these developing teachers will potentially become the model and inspiration for future Students of Color to consider teaching as a career. Through this lens, it is important to consider how their own K12 experiences shaped the current experience they have in teacher education coursework.

2. Literature Review

Across multiple contexts, the literature shows that Students of Color must demonstrate exceptional resilience in order to navigate the racialized experiences of schooling; that positive, supportive interactions with faculty are a key element of building resilience and overcoming barriers to academic success and degree completion; and that Students of Color with less sociocultural support or without a community of understanding individuals experience lowered persistence toward degree attainment. Literature specific to Preservice Teachers of Color aligns to similar themes, and it helps to point to how the experiences of preservice teachers are reproductive within new contexts [see Ball’s [47] conceptualization of generative change]. Additionally, the literature specific to Preservice Teachers of Color reveals how white supremacy, through interest convergence and color blindness, plays a central role in maintaining a simplified notion of the problem of the teacher diversity gap. This relies on the oversimplification that the problem is mostly one of basic recruitment, rather than also being strongly linked to teacher retention as well as the culture and climate of K12 schools as critical education scholars have argued [5,6].

In centering issues of race, the need for both K12 educational leaders, as well as teacher educators and policy-makers, to consider how to decenter whiteness through systematic critical examinations of current climate and culture and how it is reproduced and maintained by the policies and practices within these spaces becomes paramount.

2.1. Barriers to Persistence

Empirical studies—both within teacher education and in other fields such as science and technology—concur that Black American and Latinx students must embody exceptional persistence and motivation needed to complete their undergraduate degrees. This is due to a variety of barriers including not feeling welcome in higher education environments [48] and a lack of a community of understanding and supportive individuals [4,49,50,51,52,53,54]. More subtle and implicit barriers also interfere with persistence.

Microaggressions contribute to feelings of alienation for many Students of Color [55]. Even worse, the literature demonstrates that when Students of Color respond directly to microaggressions, it generally leads to further, more explicit, aggression and accusations [55,56]. Scholarship on microaggressions in a higher education context suggests that the influence of regular exposure to microaggressions can result in Students of Color poor academic performance, changing majors, or dropping out of college altogether [55,56,57].

Stereotype threat also poses a barrier for students who might internalize repeated exposure to white supremacist culture, in general, and microaggressions, in particular [50]. Massey and Owens [58] found that when African-American college students internalize negative stereotypes they are more likely to suffer academically, potentially “living up to negative group stereotypes” (p. 558). Smith [57] defines the collective consequence of implicit racial assaults as “racial battle-fatigue” in his discussion of how they impact Faculty of Color in higher education (p. 179). Minikel-Lacocque [56] points out that it is necessary to look beyond only academic outcomes and more broadly at the college experiences of minoritized students if we are to understand and begin to improve circumstances for college Students of Color.

2.2. Resilience and Resistance to Deficit Narratives

Rather than allowing exclusionary racialized environments to act as barriers, some studies demonstrate that Black and Latinx students and scholars leverage these experiences as a way to motivate themselves and build resiliency [55,59,60]. One way that Students of Color have embodied resilience in the face of barriers such as these is to develop intentional spaces for People of Color within higher education settings. One such example is the development of “social and academic counterspaces” wherein they can safely navigate their experiences of marginalization and persist in their goals [55] (p. 660). The development of such spaces is part of “resistance practices,” what Solórzano and Villalpando define as “oppositional behaviors and critical resistant navigational skills” as cited in [61] (p. 264).

Scholarship in response to the teacher diversity gap suggests that institutions and researchers must work to resist deficit narratives while examining and developing support for marginalized students. Unsurprisingly, Bourke and Jayman [62] found that students are resistant to being defined in terms of where they need to improve. Though it is vital to recognize, analyze, and advocate against both individual bias and the systemic problems that compromise Student of Color persistence, this problem-based focus has a tendency to reify deficit narratives that further act to oppress Students of Color and perpetuate low expectations on the part of faculty [62,63].

Recent transformative action research demonstrates significant success with asset-based approaches such as in the enactment of CRCTC and other Culturally Relevant Pedagogies. Jackson, Sealy-Ruiz, and Watson [29] examined a mentoring program for African-American and Latino male high school students that employed the concept of reciprocal love through a gardening metaphor as a focus on capacity rather than deficit: “our public schools need more adults who imagine themselves as seed people whose purpose is to cultivate the academic, social, and emotional success of these young men” (p. 396). In their examination of the experiences of preservice science Teachers of Color, Mensah and Jackson [64] point to a need to purposefully examine issues of racism and power that pervade our educational spaces at every level. This scholarship confirms the work of Brown [20] in his meta-analysis of the literature on Preservice Teachers of Color.

2.3. Experiences of Preservice Teachers of Color in Teacher Education

Brown [20] undertook a Critical Race Theory (CRT) analysis of the existing literature on Preservice Teachers of Color and found that Preservice Teachers of Color enter the path to become teacher with exceptional sensitivities to racialized educational spaces along with an understanding of how to navigate them. The empirical work of several scholars confirmed that these experiences often lead to Preservice Teachers of Color developing a social justice stance as their primary drive to become teachers [65,66,67]. Another theme that Brown [20] identified and that is confirmed by other scholars was the lack of connection and support that Preservice Teachers of Color experienced in higher education coursework as well as an absence of any attempt to center their racialized K12 experiences in ways that would help them develop the culturally relevant skillset required to navigate teaching a racially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse population of students in future classrooms [67,68,69].

In contrast to those findings, Brown [20] also pointed out instances where a tendency to assume a socially just stance in Preservice Teachers of Color led to further disconnections as well as a lack of purposefully developing them as culturally responsive educators. In concert with this was a tendency to erase the important distinctions that discreet cultural and ethnic identities bring into play when considering the complex spaces of teaching and learning [65]. Despite collective assumptions made by much of the literature, Preservice Teachers of Color do not automatically enter the teacher preparation pipeline with a set of innate culturally responsive skills at their disposal [5,70]. This “essentializing” the diversity among Teachers of Color into one homogenous group is an effect of white supremacy and hegemonic forces [20] (p. 337), which contributes to the problem of stereotype threat and a reifying of tokenism [71]. It can also compound the problem of Preservice Teachers of Color feeling isolated and like an outsider if their positionality does not align with teacher educator assumptions [72].

For the purposes of this study, Brown’s [20] discussion of the implications of the existing literature on Preservice Teachers of Color for examining the teacher diversity gap are perhaps the most enlightening in two specific respects: (a) the conspicuous lack of explicit discussion of racism and racialized experiences in most of the studies examining the experiences of Preservice Teachers of Color; and (b) a focus on the individual responsibility for Teachers of Color to resolve the issues related to the teacher diversity gap. Both of these findings illuminate the pervasive problem of interest convergence in how the issue is continually framed. This pervasive colorblindness in much of the existing literature and abdication of responsibility for critical self-reflection on the part of educational scholars, policy-makers, and teacher educators simplifies the problem of the teacher diversity gap into merely a recruitment issue rather than recognizing the need for a comprehensive examination of—alongside the development and enactment of policies needed to disrupt—white supremacist culture in K12 schools and in higher education.

3. Methods

This study engages a transformative qualitative model in that it is attempting to center the voices and needs of marginalized individuals: Preservice Teachers of Color. I focused on the following criteria for transformative framework methodology developed by Mertens [73] and adapted by Sweetman, Badiee and Creswell [74]: (a) situating the problem within a community that has experienced marginalization; (b) use of a critical theoretical lens; (c) research questions written with a stance toward advocacy; (d) the literature review includes discussions that primarily relate to diversity and marginalization; (e) the labeling of participants was carefully guided by critical literature and by their own self-identifications; and, (f) the discussion of findings focused on bringing attention to in order to disrupt racism within education.

As an emerging critical teacher education scholar and career-long social justice advocate, I identify white supremacy and colorblindness as the key barriers not only to racial justice in society, but also specifically to diversifying the teacher workforce. Engaging CRCTC as a framework is in keeping with the transformative intent of the study. The semistructured interview guide was based on the elements of this critical framework and, during interviews, I used political clarity and self-revelation to make my subjectivities, biases, and anti-racist intent as clear as possible for participants. I am deeply committed to self-reflexivity in order to be acutely attuned to race, bias, and privilege. Indeed, it is the leading lens with which I approach my own teaching and collegial interactions within educational spaces as well as my scholarship. It is important to note that I do not see my allyship and social justice advocacy as binary or terminal, but rather as a consistent journey of critical self-awareness, inquiry, and humility.

As described previously, this study is derived from a larger mixed-methods dataset that also employed critical transformative methods. This smaller study focuses narrowly on the data from the eight Preservice teachers and how they experienced K12 education and, in turn, how those experiences affected their choice to become a teacher and their experiences in current teacher education coursework. The data analyzed for this study was narrowed through inductive and deductive coding of the larger study (See Table 1, below, for the initial coding tree from the original dataset).

Table 1.

Original Coding Tree from Original Mixed-Methods Dataset.

The data identified initially under the larger themes of “Positive K12 Experiences” and “Negative K12 Experiences” were re-examined for this study and coded inductively and deductively using CRCTC with focus on the guiding research question: How have previous K12 educational experiences of Preservice Teachers of Color affected their pathway to pursue teaching as a career?

3.1. Participants

Eight participants were interviewed who fit the criteria of Preservice Teacher of Color as defined by how they self-identified on a survey about CRCTC (that was part of the larger study). Fifteen participants were initially selected for interviews purposively, based upon having a reasonably consistent proportional alignment to the general racial and ethnic categories used by the College of Education in which the study was undertaken. Further criteria limited the participants to those who had taken teacher education coursework within the last year and to those who were still pursuing a teaching license at the time of the study. Table 2, below, provides the description of the participants according to how they self-identified during the interviews (all names are self-selected pseudonyms).

Table 2.

Interview Participants.

Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis Procedures

Because CRCTC has primarily been studied in the context of K12 teachers and students [19,21,29,30,31,75], there is no existing validated instrumentation aligned to CRCTC in higher education. Thus, the semi-structured interviews explored what elements of critical care were specifically relevant to these participants. The interview did this by asking about the tenets related to CRCTC specific to their K16 educational experiences. I also created interview guides for faculty and students that additionally incorporate Gay’s [13] Culturally Responsive Teaching framework. In particular, the question of how Students of Color view faculty coursework design as culturally responsive and how they view their instructional and relational choices as indicative of critical teacher is under focus.

The individual interviews were initially transcribed and coded for the larger study both inductively and deductively using holistic or macrolevel coding [76]. For the purposes of this study, codes related to the macro theme of K12 experiences were isolated and those sections of text were recoded and refined with a focus on categorizing experiences among macro themes and sub-themes. With this second round of refined coding, themes also emerged from how the participants described observations of inservice teachers during field experiences in K12 schools that corresponded to their own K12 narrated experiences. Thus, data related to their own K12 experiences as well as observations of K12 experiences during their teacher education coursework are included in this data set. After the second round of refined coding, codes were arranged into common themes using a process of thematic coding known as “metasynthesis” [76]. Table 3, below, demonstrates the thematically arranged coding tree with code frequencies.

Table 3.

Thematically organized coding tree with code frequencies.

In order to increase trustworthiness, I employed a relatively novel technique to leverage the transformative potential of member-checking known as Synthesized Member Checking [77] that has participants re-examine their data after a period of time to reconsider findings and implications. However, a limited number of participants chose to engage in the member-checking process (at the time of publication of this article, four of the eight interview participants responded to and engaged in the member-checking process). Triangulation is demonstrated by the themes that were identified through similar experiences across multiple or more participants and/or narrated events.

3.2. Researcher Positionality

As a white ally and social justice educator, I am deeply committed to self-reflexivity in order to be acutely attuned to race, bias, and privilege. Indeed, it is the leading lens with which I strive to approach my own teaching and collegial interactions within educational spaces as well as my scholarship. It is important to note that I don’t see my allyship and social justice advocacy as binary or terminal, but rather as a consistent journey of critical self-awareness, inquiry, and humility. The original larger study and this more focused study has grown organically out of my own experiences of teaching and learning over the last 15 years, alongside my developing understanding of how methodology and scholarship shape the work of teacher educators and, correspondingly, the experiences of developing teachers. I am drawn to, as well as concerned by, the circle of teaching and learning influences, encourages, and/interrupts our understandings of the world through the preK–16 education process: when centered in love, inquiry, and humility this process can be revolutionary and emancipatory; when centered in dominance and assumptions, this process is a hegemonic and oppressive wheel of reproduction. I seek to pursue a scholarly praxis that works to disrupt that wheel.

4. Findings and Analysis

The qualitative findings and analysis of those findings are arranged in sections aligned to the themes across two large macro themes “Positive/Negative Experiences in K12 Settings,” and within those two macro themes are the subthemes-based common experiences across participants. In addition, coded data were arranged under the themes of “Connections to Choosing Teaching as a Career” and “Persistence/Resilience.”

It is important to recognize the complexity of the experiences of these participants. While the data is arranged in a somewhat hierarchical structure, there are many places where one narrated experienced connected with multiple themes. While Table 3 demonstrates coding frequencies, the frequency in and of itself is not solely demonstrative of the importance or relevance of each theme. Still, the largest number of codes by far fell within the category/subcategories relating to negative K12 experiences.

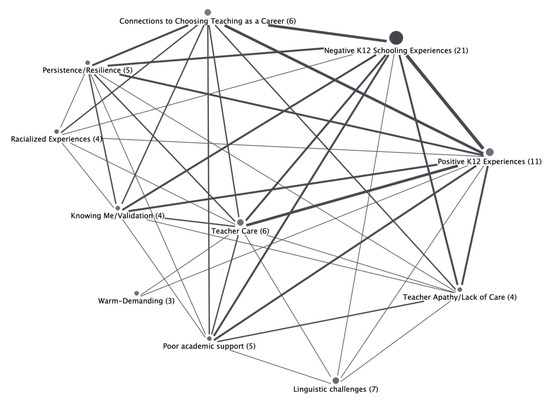

In order to help visualize the complexity and connections among the themes, I created a code map using the analysis program MAXQDA (see Figure 1, below). The size of the graphic dot is relational to the number of codes within that theme. The line width indicates the frequency of co-occurrence of themes within the documents.

Figure 1.

Code map demonstrating code frequencies and co-occurrences among K12 experiences.

4.1. Positive K12 Experiences

While most participants could only remember and narrate one or two detailed positive experiences from their K12 schooling, most presented these as a contrast to what the rest of their experiences were. The notable exception to this was Aamu, a Pakistani-born, female, Asian-American citizen. She was the only participant in the study who had only positive memories of her K12 schooling, which was limited to the third grade since she was homeschooled after that point until college. This was an unexpected finding, but an important one that points to the complex interplay of identity and experience.

4.1.1. Knowing Me

The theme of feeling a relational connection to teachers showed up across participant experiences. Liz, a Hispanic-Latina, Christian described how after one year with a math teacher who never waited for her to answer when called on, she developed a terrible phobia about math class. She then explained:

I did get a better teacher actually. She took time to try to teach you the math, and I think that was one of the best experiences… because she knew my frustration about like participating, especially if it was like on the spot. So I would run away to the bathroom and then come back, and she would understand what I did because I didn’t want to actively participate, [and be] put on the spot and that way. I would much rather be in like my own little area.

Other participants explained how when teachers remembered their names, and things from their family, or how they learn best, it created a positive memory. Jess, a female, Catholic, Hispanic-Mexican-American preservice teacher, described a meaningful point in her high school experience when she chose to leave the International Baccalaureate program she had been in at the end of her eleventh-grade year. She explained that all but one of her teachers were very angry with her and repeatedly told her that leaving now was just a “waste” of the last three years. One teacher, however, responded to her choice quite differently:

He was like, “I, I agree with you. […] You’ve learned so much. He, he told me so you haven’t wasted your time. He was like, you’ve learned so much and even though you don’t continue it, you already have all that experience. […] And that was the only person out of all my teachers, out of the counselors that have any administration that I talked to that told me that. So I was like, thank you. Like, you know, he…first of all he heard me out, which is something where I was like, he heard out my reasonings ….

Ani, an African-American, Christian, female, explained how, since her friends were role models for her, that is what made school enjoyable: “I guess my motivations were my friends and having friends who were always, um, not always, but who did well in school, so wanting to be that way helped me as well.” Alana, a Mexican, female explained that even though her grade school and middle school experiences were mostly negative memories, she remembers her experiences with her peers in band as very positive “It was like a family to me.”

These relational experiences echo what other studies of Students of Color have found. The positive experiences of these participants who have chosen to pursue teaching and are successful so far in their journey is especially meaningful given that the literature shows that two of the most common barriers for persistence towards a college degree for Students of Color are not feeling welcome in higher education environments [48] and a lack of a community of understanding and supportive individuals [4,49,50,51,52,53,54].

4.1.2. Warm Demanding

This experience of feeling known also showed up in the context of participants describing when they felt pushed to do better by a teacher. Ellen, a Black 25-year-old female, described a situation where a Black female teacher stopped her from getting into a fight with another girl:

Ms. Kyree comes out and she’s, she’s like, Ellen, you get in here. We go inside, and she, um, she sits us down, and she was like, you will not be the average black girl at this school. She’s like, “You will not sit here and get into these cataclysmic fights.” She said, “You need to be better. You need to do more. […] There aren’t very many black people as it is. Don’t get kicked out of one of the top schools in the city because you want to fight this girl. Be better than that. Don’t be the stereotypical black kids. So when they come in and they’re like, ‘Oh that black girl always…’ don’t let that be you!” And I’m like, okay. So I felt like she came. I love that.

This construct, perhaps best described as a disposition, combines the idea of high expectations with responsive care. Even though not all of the participants directly shared a story of a warm-demanding experience, several explained exactly this disposition when describing the kind of teacher they hope to become. Ellen explained “when you actually intentionally care about someone, you want them to be the best.” Liz described a warm-demanding care by articulating the links among love, critical feedback, and positive motivation. Her description is closely aligned to the CRCTC construct of Critical Hope [28]:

I think as teachers we should be giving them [K12 students] that, that sense of hope that hey, you know, there’s, there’s a better road than, and then uh, what you think, what you think you’re capable of. You can do so much more. […] I think like love goes a long way to so showing that, that um, that care, like in their work, like giving that positive reinforcement. I’m not putting them down…but there is some sometimes or you have to like give a little bit more feedback.

4.1.3. Teacher Care

The theme of how teachers showed care were usually narratives of positive experiences in K12 schooling. Nayeli, a 25-year-old Christian, Hispanic female, explained, “I think I had the best and worst of both worlds. I had teachers who really cared for me and helped me, gave me that extra aid that I needed to be successful.” Ellen explained that her middle school experience was mostly negative, with one exception. “And then through middle school I felt like the only teacher that really cared was my math, the African American math teacher.” Alana described her third-grade teacher with fondness “I’ll always remember that she was always seemed happy to be there and she, she messed around with us. She, she just gave you that care you wanted I guess, or I wanted from a teacher.” It was meaningful that these experiences for all but one of the participants were explained as exceptions to the normal experience of being in a K12 school. Likely, most teachers would profess that they care about students. Yet, there is clearly a disconnect among what most of these participants experienced as “normal” and what we anecdotally expect from “caring” teachers. It provides yet another piece of evidence to disrupt the status quo and to consider new ways of examining the climate and culture of K12 contexts with political clarity.

4.2. Negative K12 Experiences

This group of Preservice Teachers of Color narrated nearly twice as many negative experiences as positive ones. For example, Ellen explained that the majority of her high school experiences made her feel like an outsider. “And then in high school I felt like the teachers, they picked their favorites, or they picked who they liked the most and they just stuck to them and the rest of us just got the sloppy seconds.” She also described a situation in middle school where the curricular choices confirmed what she felt as an outsider status. She was asked by a seventh-grade teacher to interview her family about their ancestors so that they could then create a European-style coat-of-arms:

She said we’re going to, I want you guys to go home and learn about your, your family’s origin and like, just learn about it. And I’m just like, I don’t ... So I went home and I was like, “Dad, where did we come from?” And he was like, “Africa.” And I was like, do you know any of our history? He said, “Ellen, were Black slaves. We came from Africa. That’s all I got for you.” And I’m like, even beyond that, my dad should have been able to like … But that’s just information that wasn’t given to us, but for you [the teacher] to make a whole assignment about it. And then when I went to talk to her about it, I said “My dad doesn’t know.” She said, “well you can do Kenya, here.”

Ellen’s experience of exclusion in this story resonates with how the findings of Mensah and Jackson [64] framed scientific knowledge as white property. Here, ancestral and historical knowledge are framed in precisely the same way. The additional lack of context related to the legacy of slavery, colonization, and genocide is particularly problematic when viewed from a systemic lens. Adopting political clarity might allow for this teacher to prompt her students to question who gets the privilege to trace their ancestral roots and have historical customs chosen as the norm for classroom experience. Although this was Ellen’s story, it resonates far beyond one individual microaggressive experience and reveals the hegemonic culture of that classroom.

4.2.1. Teacher Apathy/Lack of Care

Multiple participants described apathy and lack of care of the normal experience they had in schools. For example, Nayeli shared:

They really don’t care. They teach whatever they want and at the end if they hit the standard, if they did it, it doesn’t matter. I had a class where it was departmentalized and in reading the same exact assignment for three weeks, I have no idea what I learned. Nothing. Because those teachers, they don’t care. I walked into their classroom, I sat there, I wasted four days trying to do my brainstorming because the teacher didn’t care to come and help me. She just sat in the back and just read her newspapers.

And Jess explained a lack of care throughout her middle and high school years that affected her perception of herself and her academic abilities:

And I think because I never had that, let’s say like I never had a teacher that told me that [I was smart] or I never had a teacher that was like, Oh, good job on this. I always did good in my heart a little bit, and now I’m like, man, I wish someone would have told me I was smart. My mom would tell me I was smart and my brother and my sister and they didn’t go to college. So it’s always been like, oh, but I just thought it was normal and now I’m like, Oh, you know, I do … like, I’m smart, I’m intelligent, I do work hard, and like I should be glad to be where I am. And that’s not something till I realized until now. So, and which is sad because like, I wish I knew that throughout my high school or middle school years, but that’s, I guess the teacher never really. They never really cared, I personally never found care.

4.2.2. Poor Academic Supports

Participants also described a number of incidents that indicated a lack of appropriate academic support. Ani, an African-American Christian female, described her struggle with learning to read and the apathetic response of teachers to her struggle:

In fourth grade, I was behind in my reading and writing, so two grade levels behind in which made it difficult, um, I guess as a student to catch up with all the other students when we were doing writing lessons because it was already expected that we had learned those skills. And um, in third grade, since I had come from a different elementary school during that time, I didn’t learn those same skills. Um, and I just didn’t feel like I had teachers growing up help me through those processes.

Liz describes a similar experience in an elementary math experience:

We were counting by fives, or twos, or threes. With each child she’d look at us and she would expect us to say the next number. Every time it came my turn I didn’t know what was happening. I was kind of slow to… register, so I would look around to try and see if someone would help me. Um, and when I would spit out a number, either if it was wrong or right, she would just go to the next person, wouldn’t stop to like do a scaffolding method of correcting me of saying, you know, this is what you’re supposed to be doing. Nothing. She would just keep going and not waste your time on people that would get their answers wrong.

If care feels like being understood and held to high expectations as demonstrated in the Positive K12 Experiences theme, these stories clearly demonstrate the opposite end of that spectrum.

4.2.3. Linguistic Challenges

A number of participants in the study are bilingual. They reported negative school experiences related to learning English as well as microaggressions due to their language diversity. For example, Nayeli expressed:

I tried to ask, you know, another Hispanic student in the class, you know how you said it in Spanish, and the teacher would get mad that “Why are you speaking your language?” And I’m like, well I’m asking because I don’t know. So it was a little bit of a conflict there. So I don’t want to be that way. I strongly believe that bilingualism helps you so much more than to speak only one language and especially in this country.

And Alana explained, “I remember just always getting, not yelled at, but more like teachers didn’t want to deal with me because I didn’t know English.”

4.2.4. Overt Racialized Experiences

Three of the participants witnessed or personally experienced overt racism in a K12 school. Liz describes an experience she had while substitute-teaching and co-teaching with another teacher who was white.

You know, it’s funny because I was subbing in a class and there was this white student causing the problem and disturbing the, the Black students. Um, he was the one that was ignored and that was in less trouble than the Black students had been. Actually, the teacher came in and she took away the Black students, and she took away one of the girls [who was] Latina. And when I asked why she took her, I said because I didn’t see she was doing anything wrong, [the teacher said] “I had to put her to do her work and she wasn’t doing what she was supposed to be doing.” Even if she was chatting like amongst her friends, they were doing something productive. And uh, she’s, she [the other teacher] said because she saw her mouth and talk back at her. And I was like, okay. And I asked the student and she’s like, “No, I was just saying that it, that the kid that she said she was in trouble didn’t do anything.” And I was just like, okay. Like, you know, I understand her, and I’m willing to hear both sides of the story. But yeah, I feel like white students aren’t even punished as harshly as someone of color and, who are even drawn attention or humiliated.

Ellen shared that she had a teacher who regularly made racist jokes during class.

Ellen: One of my teachers was very racially stupid,Interviewer: Racially stupid?Ellen: Like he made very horrible racial jokes and still has a shop, and still works there. And um, he made like to the point to where I called him [a name] one day while I was out with my dad, and my dad was like, “Why don’t you like your teacher?” […] I said, I don’t like him. I don’t listen to anything he says. Then he was like, “Why not?” And I said, because he makes horrible racial jokes. He said, “What do you mean?” and I said, one of the jokes and stuff like that and my dad, but my dad was… [makes a face to indicate how angry he was] I was like, “Dad, do not retaliate because this is my grade. Like I highly doubt they’re going to fire him because most of the kids are either afraid of him or they think he’s funny. So that’s why I haven’t said anything.” My Dad was like, “Okay, well yeah.”

Olivia, a 23-year-old Biracial female, experienced an overtly racist and deeply troubling incident of a racial slur being used by a veteran white female teacher at an elementary school during her field experiences:

Um, I, my mentor teacher and I were walking back after the bell rang, so the school day was over and another teacher came over and introduced herself. So I introduced myself as well engaged in brief conversation, and I think her and my mentor teacher were like reflecting on the school day. And then there were several kids in the courtyard and, um, I think it was two boys and a girl and the other teacher who had come over and introduced herself, called the kids over and ask them what they were doing because the bell had already rang. So she was concerned because the kids weren’t supposed to be in the courtyard. So they mentioned that their teacher had asked them to go, um, I think get tape from the office because it was the week of like, student, like elections or something was going on like that. And so she said, okay, can you kids go back to your classroom because you’re not supposed to be out here, the bells already rang. So she goes back or the kids go back and then she, the teacher who introduced herself, not my mentor teacher, leans over to me and says, “I hope you don’t think that I said that to those students because they’re Black” and me being biracial and half black. I was like, okay, well maybe you don’t know that I am black, but all right. And um, I didn’t, I recall like not saying anything, and then she goes on to say [Olivia hesitates, she is visibly uncomfortable.] I don’t know if I want to say the word—Interviewer: You can say it however … You can refer to it however you want.Olivia: I mean, I’m going to say it, but, um, it makes me uncomfortable to say it. But she said so. Yeah… So she says, you know, “I hope you don’t think that I said that because they’re black, I love niggers” and I recall being so incredibly frustrated and like my eyes started to well with tears, and I looked over at my mentor teacher to see if she was having a similar reaction, and she didn’t really have a reaction and they kind of just like, I recall there was like a brief, like chuckle, like, ha ha, whatever. And they went along with their conversation, and I turned around and went back into my mentor teacher’s classroom and gathered my stuff. And then my mentor teacher came in, and as I was getting ready to leave, I looked at her, and we made eye contact and I just said, “wow.” And she kind of looked at me like confused and not really understanding what I was referring to and then kind of took a second, and she was like, “Oh, Dr. Aller, um, yeah, yeah. She says like, she says those kinds of things,” And um, I remember I was like, “Oh, well, did I hear her correctly?” She’s like, “Oh yeah, she, she uses that word a lot, but I don’t agree with it, but you kind of just have to take it with a grain of salt.” And then I told her to have a good day, and then I would see her on Wednesday, and then I decided not to go back to elementary school because I didn’t feel like that was a place that I was welcome or respected or valued as an individual, let alone as somebody who identifies as a Black female and I didn’t feel like I could receive the education and experiences that I deserve as a student. To be the best as I can be from a person who would… from overhearing somebody say that in that context in school, referring to children…. Not that it’s ever okay to refer to anybody as that, but especially to children and then being mentored by somebody who I respected and hold in high regard to say that to take it with a grain of salt. I just didn’t feel like…. I feel like I’d be compromising my personal values and beliefs as well as my education.

Olivia’s experience is profoundly disturbing on a number of levels. While it is not surprising that both within university spaces and in K12 contexts preservice teachers encounter overt acts of racism, as well as frequent microaggressions, the lack of studies focused on exploring and disrupting the issue is somewhat surprising. While more recent studies have recently centered the experiences of Preservice Teachers of Color through the lens of CRT [20,64], the call for substantive policy change related to improving the racialized climates of schools and university remains disappointingly narrow.

4.3. Connections to Choosing Teaching as a Career

Participants connected their K12 experiences to their current pursuit of a teaching career across both positive and negative experiences. Olivia is still committed to teaching, but she talks through how the incident still causes her to question herself and the ability of schools to be safe places for Students of Color:

Has it motivated my drive? Yes. But it also, I think that it also hurts because you recognize like there you can only try to understand something so much and if you don’t personally… if it… I think that people aren’t going to be as frustrated enough as they should be if they don’t feel like it’s a personal attack. And so I think that I would love to see just society in general, but definitely the teaching profession, you know, like you, it will be my job, and as teachers it’s your job, to advocate for students. So I think that it needs to get to a place where using words like that word should make you as upset as somebody as a Person of Color. And I just don’t think we’re there yet. And that is frustrating, and it hurts because I, it’s like I’ve heard, I feel like… did I do something wrong? Do I even have the right to be mad at these people? The person who said the word, the person who doesn’t think it’s that big of a deal. My site facilitator who just seems like she doesn’t know how to handle it. Do I have the right to be mad at those people because I don’t think that word holds that weight for them because they aren’t… Because my site facilitator isn’t a person of color. My mom isn’t a person of color, so that word means so much more to me because I feel like it’s such like it’s just evaluating me as a human being. So do I have the right because I think that other people just don’t understand. So it’s … I think it’s kind of been… I’m like, juxtaposed between motivation and frustration and the fact that will things change because we do have Students of Color in classrooms, but are teachers knowing them enough and trying and fighting to know their experiences enough to, to the point that it makes them just as upset to hear those words said about them are said in general, and to be courageous enough to have a voice and speaking up against when they hear it.

Olivia’s articulate description of the tension within which she finds herself caught aptly frames the complexity of navigating the path toward becoming a teacher for many of the participants. Multiple studies have documented the need for a focused examination of racism in educational spaces and a call for political clarity on the part of teachers and teacher educators to reveal and disrupt racism [20,64,72]. The colorblind response that Olivia faced made the experience all the more traumatizing and conflicted. The teacher educator who was assigned as her field supervisor and the elementary teacher assigned as her mentor treated the event as solely an individual’s “disagreeable” (racist) action and an individual’s (Olivia’s) reaction to it as part of a normal event in teacher development. Until every teacher, teacher educator, and administrator identify such experiences as overt racism and take immediate actions to address them as well as to create dialogue for healing and understanding in the community, there will not be substantive change. Policy measures must be put in place that will hold educational leaders accountable for actively addressing racialized learning environments.

The drive to pursue teaching also grew out of positive experiences for students. Jess explained how one teacher who was always able to make the class laugh is what made the difference for her:

She made my day. She made my everything. And literally since that moment I was like, I like, I want to be like her. Like I want to make my kids laugh. Like that’s the number one thing I want to do. Like I want them to have a positive, you know, at least at school you never know what’s going on at home. So as long as they have that little burst of happiness here and that they feel comfortable with me while they’re with me, it’s like that’s what I want to achieve.

And Nayeli explained:

I feel that now because I struggled in the beginning. I have an advantage now [being bilingual]. So I think it helps me a lot, but of course it took a lot of struggle in a lot of times. The way that my teachers were with me, both negative and positive, made me want to be what I am now, because I don’t want my students to have to go through some teachers that I went through.

4.4. Persistence and Resilience

Several participants also reported how their experiences combined with messages of persistence from their families specifically built up their resilience. For example, Liz shared:

I, I know I get all these, uh, different like change your career, you know, do something different. Uh, I’ve even gotten to become a dentist or something. Do something because I’m always with my hands, but they’re just like, you know, I don’t think English is right for you if you keep making these kinds of mistakes. And I was like, well, I think I’m good in the way that I kinda like, I know it’s bad. I take every feedback, you know, and I try to make myself better, but I do kind of have that voice in the back where I’m just like, well, my ideas are different. The way I speak is probably different. Doesn’t mean I can’t teach English. It doesn’t mean that, you know, I just have that way of thinking outside the box that most people probably wouldn’t understand. […] Being like, Hispanic also means being like, like you said, very smart and making these all kinds of connections that like white people wouldn’t be able to do, you know, and with those connections, like why person will read it and be like, what is this person talking about? This doesn’t make sense to me. Whereas through I would read it and I’d be like, they know what they’re talking about. I know what they’re getting at. And so like just seeing that, getting all this criticism that just proves more to like my belief that even though I’m bilingual, even though that I’m Brown, even though that I’m Hispanic, I can do just as good as any other person that is white. […] I was always kind of a, I had a good childhood, good upbringing, good family to kind of support me in my choices. Um, I didn’t always consider myself to be smart, so I always felt like the need to just do better too. I’ve always grown up to like give my, all, have been disciplined in sitting down and reading my whole life in middle school. That’s all I did. I, I just went to the library, sit down and read. I had that discipline instilled in me. […] So there’s just a, there’s, there needs to be that, that, that inside you that want that motivation, that drive to just, I dunno, just to become better than what people would think you believe. Kind of like trying to prove them wrong.

Implicit racism and bias are potentially some of the most insidious challenges that Students of Color face, precisely because they are the most difficult to document, confront, and resist and they are deeply embedded in American normative culture [78]. These findings speak to the need for teacher educators to prioritize developing supportive and validating relationships that contribute to Student of Color resilience and persistence.

5. Conclusions

The focus on K12 experiences in this study requires us as teacher educators to consider the implications for how we develop teachers. Perhaps even more urgently, it calls for teacher educators to more purposefully partner with the schools who provide clinical settings for teacher development. We must examine how, as clinical partners with K12 schools and educational leaders, we might begin to hold one another accountable for consistently developing culturally responsive practices and policies that work to disrupt the racism that remains present in our schools and universities as evidenced by even the limited number of studies focused on preservice teachers and issues of race and racism [1,20,64]. The findings of these participants’ positive K12 experiences confirm that teacher educators must strive to develop meaningful relationships with preservice teachers, especially those who have been marginalized or present as being (or perceive themselves to be) underprepared academically. Transformative action research undertaken collaboratively within colleges of education that works to open up dialogue and create “counterspaces” [55] (p. 660) for Students of Color would be an ideal first step to developing policy that might also aid in the push to reveal the racialized culture and climate of schools and to disrupt it in order to restore justice and equity. In order to do this, teacher education scholars must recognize the pervasive intransigency of colorblindness and interest convergence as the most dangerous barrier for desperately needed change in teacher preparation. Documentation of these experiences will always be an important part of our praxis, but we must also explore transformative solutions related to both praxis and policy development if we are to enact the sweeping change needed.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Sleeter, C.E. The Academic and Social Value of Ethnic Studies: A Research Review; National Education Association (NEA): Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bitterman, A.; Gray, L.; Goldring, R. Characteristics of Public and Private Elementary and Secondary Schools in the United States: Results from the 2011–12 Schools and Staffing Survey (NCES 2013–312); U.S. Department of Education; National Center for Education Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2013.

- National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). Racial and Ethnic Enrollment in Public Schools, 223. 2014. Available online: http://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cge.asp (accessed on 8 October 2018).

- Putman, H.; Hansen, M.; Walsh, K.; Quintero, D. High Hopes and Harsh Realities: The Real Challenges to Building a Diverse Workforce; Brookings Institution, Brown Center on Education Policy: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sleeter, C.E.; Milner, R. Researching successful efforts in teacher education to diversify teachers. In Studying Diversity in Teacher Education; Ball, A.F., Tyson, C.A., Eds.; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Lanham, MD, USA, 2011; pp. 81–103. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, L. Recruiting and Retaining Teachers: Turning Around the Race to the Bottom in High-Need Schools. J. Curric. Instr. 2010, 4, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll, R.; Merrill, L. Who’s Teaching our Children? Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD): Alexandria, VA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Podolsky, A.; Kini, T.; Bishop, J.; Darling-Hammond, L. Solving the Teacher Shortage: How to Attract and Retain Excellent Teachers; Learning Policy Institute: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gershenson, S.; Hart, C.M.; Hyman, J.; Lindsay, C.; Papageorge, N. The Long-Run Impacts of Same-Race Teachers; National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER): Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Neal, L.I.; Sleeter, C.E.; Kumashiro, K.K. Introduction: Why a diverse teaching force must thrive. In Diversifying the Teacher Workforce: Preparing and Retaining Highly Effective Teachers; Sleeter, C.E., Neal, L.I., Kumashiro, K.K., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 107–485. [Google Scholar]

- Boggess, L.B. Tailoring New Urban Teachers for Character and Activism. Am. Educ. J. 2010, 47, 65–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chubbuck, S.M. Individual and Structural Orientations in Socially Just Teaching: Conceptualization, Implementation, and Collaborative Effort. J. Educ. 2010, 61, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, G. Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice, 2nd ed.; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, Z. Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students; Corwin: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings, G. Culturally Relevant Pedagogy 2.0: A.k.a. the Remix. Harv. Educ. 2014, 84, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, A.; Sharma, S. “Now I Look at All the Kids Differently”: Cracking Teacher Candidates’ Assumptions about School Achievement in Urban Communities. Action Teach. Educ. 2016, 38, 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, C.M. A study of culturally responsive teaching practices of adult ESOL and EAP teachers. J. Res. Pract. Adult Lit. Second. Basic Educ. 2013, 2, 170–183. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela, A. Subtractive Schooling: U.S.-Mexican Youth and the Politics of Caring; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Whipp, J.L. Developing socially just teachers: The interaction of experiences before, during, and after teacher preparation in beginning urban teachers. J. Teach. Educ. 2013, 64, 454–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.D. Teaching in color: A critical race theory in education analysis of the literature on preservice teachers of color and teacher education in the U.S. Race Ethn. Educ. 2014, 17, 326–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.A. Toward a theory of culturally relevant critical teacher care: African American teachers’ definitions and perceptions of care for African American students. J. Moral Educ. 2010, 39, 449–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noddings, N. The Challenge to Care in Schools: An Alternative Approach to Education, 2nd ed.; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Beauboeuf-Lafontant, T. Womanist Lessons for Reinventing Teaching. J. Educ. 2005, 56, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, J.J. (Ed.) In Search of Wholeness: African American Teachers and Their Culturally Specific Classroom Practices; Palgrave: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, F. Warm demander pedagogy: Culturally responsive teaching that supports a culture of achievement for African American students. Urban Educ. 2006, 41, 427–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G. But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory Pract. 1995, 34, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G. Toward a Theory of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy. Am. Educ. J. 1995, 32, 465–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambacher, E.; Bondy, E. Creating Communities of Culturally Relevant Critical Teacher Care. Action Teach. Educ. 2016, 38, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, I.; Sealey-Ruiz, Y.; Watson, W. Reciprocal love: Mentoring black and Latino males through an ethos of care. Urban Educ. 2014, 49, 394–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, W.; Sealey-Ruiz, Y.; Jackson, I. Daring to care: The role of culturally relevant care in mentoring Black and Latino male high school students. Race Ethn. Educ. 2016, 19, 980–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolón-Dow, R. Critical Care: A Color(full) Analysis of Care Narratives in the Schooling Experiences of Puerto Rican Girls. Am. Educ. J. 2005, 42, 77–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilder, M. Increasing African American teachers’ presence in American schools: Voices of students who care. Urban Educ. 2000, 35, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, L.C.; Amanti, C.; Neff, D.; Gonzalez, N. Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory Pract. 1992, 31, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosso, T.J. Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race Ethn. Educ. 2005, 8, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comber, B.; Kamler, B. Getting out of Deficit: Pedagogies of reconnection. Teach. Educ. 2004, 15, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios-Aguilar, C. Measuring funds of knowledge: Contributions to Latino/a students’ academic and nonacademic outcomes. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2010, 112, 2209–2257. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Thirtieth Anniversary ed.; Continuum: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. The Politics of Education: Culture, Power, and Liberation; Bergin & Garvey: South Hadley, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolomé, L. Beyond the methods fetish: Toward a humanizing pedagogy. In The Critical Pedagogy Reader, 2nd ed.; Darder, A., Baltodano, M.P., Torres, R.D., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2009; pp. 338–355. [Google Scholar]

- Beauboeuf-Lafontant, T. A Womanist Experience of Caring: Understanding the Pedagogy of Exemplary Black Women Teachers. Urban Rev 2002, 34, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darder, A. Freire and Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gorski, P. Reaching and Teaching Students in Poverty; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gorski, P. Unlearning deficit ideology and the scornful gaze: Thoughts on authenticating the class discourse in education. Counterpoints 2011, 402, 152–173. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan-Andrade, J. Note to Educators: Hope Required When Growing Roses in Concrete. Harv. Educ. 2009, 79, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyon, J. Race, social class, and educational reform in an inner-city school. Teach. Coll. Rec. 1995, 97, 69–94. [Google Scholar]

- Anyon, J. Social class and school knowledge. Curric. Inq. 1981, 11, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, A.F. Toward a Theory of Generative Change in Culturally and Linguistically Complex Classrooms. Am. Educ. J. 2009, 46, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, M.R.; Byron, R.A.; Ferry, G.; Garcia, M. Food for thought: Frequent interracial dining experiences as a predictor of students’ racial climate perceptions. J. High. Educ. 2013, 84, 569–600. [Google Scholar]

- Arana, R.; Castañeda-Sound, C.; Blanchard, S.; Aguilar, T.E. Indicators of Persistence for Hispanic Undergraduate Achievement: Toward an Ecological Model. J. Hisp. High. Educ. 2011, 10, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beasley, M.A.; Fischer, M.J. Why they leave: The impact of stereotype threat on the attrition of women and minorities from science, math and engineering majors. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2012, 15, 427–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, V.; Kerby, S. The state of Latinos in the United States; Center for American Progress: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, M.; Wright, C.; Espinosa, L.; Orfield, G. Inside the Double Bind: A Synthesis of Empirical Research on Undergraduate and Graduate Women of Color in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. Harv. Educ. 2011, 81, 172–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlston-Wilson, V.; Saavedra, S.; Chauhan, S. From Access to Completion: A Seamless Path to College Graduation for African American Students; National Urban League, Washington Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.; Serna, I. Making College Happen: The College Experiences of First-Generation Latino Students. J. Hisp. High. Educ. 2004, 3, 146–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosso, T.; Smith, W.; Ceja, M.; Solorzano, D. Critical Race Theory, Racial Microaggressions, and Campus Racial Climate for Latina/o Undergraduates. Harv. Educ. 2009, 79, 659–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minikel-Lacocque, J. Racism, college, and the power of words: Racial microaggressions reconsidered. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2013, 50, 432–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.A. Black faculty coping with racial battle fatigue: The campus racial climate in a post-Civil Rights era. In A Long Way to Go: Conversations about Race by African American Faculty and Graduate Students at Predominantly White Institutions; Cleveland, D., Ed.; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 171–190. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D.S.; Owens, J. Mediators of stereotype threat among black college students. Ethn. Rac. Stud. 2014, 37, 557–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yosso, T.J. Critical Race Media Literacy: Challenging Deficit Discourse about Chicanas/os. J. Popul. Film Telev. 2002, 30, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solórzano, D.G. Critical race theory, race and gender microaggressions, and the experience of Chicana and Chicano scholars. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 1998, 11, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.S.; McKissic, S.C. Drawing sustenance at the source: African American students’ participation in the black campus community as an act of resistance. J. Black Stud. 2010, 41, 264–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourke, A.; Jayman, A.J. Between vulnerability and risk: Promoting access and equity in a School-University partnership program. Urban Educ. Issues Ideas Public Educ. 2011, 46, 76–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, C.E.; Haig-Brown, C. Returning the dues: Community and the personal in a university-school partnership. Urban Educ. 2001, 36, 226–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, F.M.; Jackson, I. Whiteness as property in science teacher education. Teachers Coll. Rec. 2018, 120, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Au, K.H.; Blake, K.M. Cultural identity and learning to teach in a diverse community: Findings from a collective case study. J. Teach. Educ. 2003, 54, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyton, E.; Saxton, R.; Wesche, M. Experiences of diverse students in teacher education. Teach. Educ. 1996, 12, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellez, K. Mexican-American preservice teachers and the intransigency of the elementary school curriculum. Teach. Educ. 1999, 15, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, M.L.; Rodriguez, T.L.; Agosto, V. Who are Latino prospective teachers and what do they bring to US schools? Race Ethn. Educ. 2008, 11, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meacham, S.J. Black self-love, language, and the teacher education dilemma: The cultural denial and cultural limbo of African American preservice teachers. Urban Educ. 2000, 34, 571–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas, A.M.; Davis, D.E. Preparing teachers of color to confront racial/ethnic disparities in educational outcomes. In Handbook of Research on Teacher Education, 3rd ed.; Cochran-Smith, M., Feiman-Nemser, S., McIntyre, D.J., Demers, E.K., Eds.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, and the Association of Teacher Educators (ATE): New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 583–605. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, H. Racial Tokenism in the School Workplace: An Exploratory Study of Black Teachers in Overwhelmingly White Schools. Educ. Stud. 2007, 41, 230–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheruvu, R.; Souto-Manning, M.; Lencl, T.; Chin-Calubaquib, M. Race, isolation, and exclusion: What early childhood teacher educators need to know about the experiences of pre-service teachers of color. Urban Educ. Issues Ideas Public Educ. 2015, 47, 237–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, D.M. Mixed methods and the politics of human research: The transformative-emancipatory perspective. In Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research; Tashakkori, A., Teddlie, C., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 135–164. [Google Scholar]

- Sweetman, D.; Badiee, M.; Creswell, J.W. Use of the Transformative Framework in Mixed Methods Studies. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antrop-González, R.; De Jesús, A. Toward a theory of critical care in urban small school reform: Examining structures and pedagogies of caring in two Latino community-based schools. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2006, 19, 409–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Birt, L.; Scott, S.; Cavers, D.; Campbell, C.; Walter, F. Member checking: A tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1802–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giroux, H.A. Foreword. In Culture and Difference: Critical Perspectives on the Bicultural Experience in the United States; Darder, A., Ed.; Bergin & Garvey: Westport, CT, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).