Abstract

This reflective, autoethnographic qualitative case study at focus in this article is based on broader research on the experiences of Black teachers working at predominantly white and affluent private schools in the United States. It was motivated by the author/researcher’s own experiences of personal, academic, and professional racial identity development as a student, educator, parent, and educational administrator while living and working in predominantly white and affluent communities. The two main research questions this study engaged were: (1) How did the author/researcher develop her Black identity as a transracial adoptee living at the intersection of race and class; and, (2) What was the author/researcher’s journey towards her present state of racial self-acceptance and understanding? Three ancillary research questions were also engaged: (a) How did social and societal factors influence the author/researcher’s racial identity development? (b) How did the author/researcher build a support network of personal and professional community? and, (c) How was the author/researcher able to get to a place of self-love? Using Hill Collins’ (1998) intersectional analysis framework and Cross’s (1991) theory of Black racial identity development, this article explores the author/researcher’s experiences as an affluent racialized minority by unpacking lived experiences, coping strategies, and support mechanisms that led to her current professional calling.

1. Introduction

Life experiences and exposures teach us that there are different acceptable modes of behavior depending upon the situation and culture in which one finds oneself. As we experience more of the world, we develop coping strategies to accommodate our new truths that guide our actions as we navigate life. According to widely accepted psychological theory, coping strategies are generally either cognitive (requiring you to think differently) or behavioral (requiring you to alter how you behave) [1]. What happens when our identity, the truths about ourselves, clashes, daily, with the world in which we work, and even live? What coping strategies are incorporated in to a person’s daily interactions and how do these strategies impact individual identity? “No one knows precisely how identities are forged, but it is safe to say that identities are not invented: An identity would seem to be arrived at by the way in which the person faces and uses his experience” [2] (p. 189). Baldwin argues that identity development is a process that begins with reflection and ends in action. Our identity develops nationally, spiritually, by gender, by sexual orientation, across class lines, and on multiple levels; too many to name. However, for members of racially minoritized groups it is often their racial identity that they identify with most vehemently. What are the experiences and coping strategies of people who identify with a minoritized racial group while working and living within a majority white and affluent environment? This introspective piece uses intersectionality to examine my journey to self-acceptance as an African American woman living and working in predominantly and white spaces.

The American Heritage Dictionary (2015) defines the term racialized as “to impose a racial character or context on” [3] (p. 1384). I consider myself a racialized minority because, while I have lived an economically privileged life, there has never been a time in my life when society failed to remind me in a negative way that I was Black. I often felt that the class privilege I have been afforded was borrowed, or even accidentally obtained. When considering my experiences at the intersection of race and class as racialized, several questions come to mind: How do African Americans cope with the racialized minority experience to become contributing and respected community members? How do African Americans develop a healthy Black identity within a negatively race-charged environment? In what ways and to what extents can outside forces, like mentors, friendships, diversity gatherings, etc., mitigate the negative impacts of racism? How do racialized minorities reflect upon their personal, academic, and work experiences and choices to develop individually and professionally? These questions are explored in this autoethnographic study of my experiences as a Black woman.

2. Problem Statement

I was adopted in 1971 to a white family in Maryland. My adoptive parents, who had already had three biological (white) children prior to adopting me, planned to adopt a second Black child a few years later so that I would not be the only Black person in my family. However, in 1972 the National Association of Black Social Workers (NABSW) protested transracial adoptions [4]. In September of 1972, the NABSW published their “Position Statement on Trans-Racial Adoption” which included the belief that “only a Black family can transmit the emotional and sensitive subtleties of perception and reaction essential for a Black child’s survival in a racist society” [4] (p. 373). According to the NABSW, I was doomed to a life of confusion and pain because growing up in a white home would not afford me the opportunity to “receive the total sense of [myself] and develop a sound projection of [my] future” [4] (p. 377). The NABSW believed that only Black parents could teach Black children the coping techniques that enabled them to flourish against institutionalized racism and racist individuals [4]. This autoethnographic study documents my experience as a racialized minority, adopted by a white family, now raising a Black family while living and working in predominantly white and affluent communities and institutions. Even though just between 1968 and 1972 approximately 50,000 Black children were adopted transracially [5] (para. 1), few studies have documented the identity development of African American adults who were products of transracial adoptions. This article uses intersectional analysis as a tool through which to reflect my voice about, and my lived experiences of, first, Black identity development, transracial adoption, and racialized minoritization in predominantly white and affluent communities, and, second, self-acceptance.

3. Statement of Purpose

Research on race and racial policy lacks depth and validity if the researcher ignores the tangled relationship between race and class in American society. Race and class intersect in such a way that examining one without the other ignores the social, political, and historical context. In addition, examining identity development without consideration of the effects of race and class also ignores the context in which that development is occurring. McFarlane [6] called race and class “overlapping categories of identity that lead to significant, yet often unacknowledged, differences in material conditions and life opportunities” (p. 163). If race, class, and identity are so interconnected, why is it that research on the effects of class on racial identity development is limited, at best?

Sociologists have often used an intersectional approach to study the growth of the Black middle class. This Black middle class, and more affluent Blacks, often use money to purchase homes in wealthy white suburbs in the ‘best’ school districts. McFarlane [6] argues that “through their wallets and educational or professional attainments they gain access to some of the privileges, goods, and services formerly reserved exclusively for Whites” (p. 165). This rise of the Black middle class has developed generations of Black children who have been raised with the privileges that money has afforded them. However, McFarlane [6] refers to this Black middle class as “operatively White” because their “access is contingent and sometimes unpredictable” (p. 165). While middle-class and affluent Blacks can receive the privileges money can buy, like the highest performing schools and comfortable housing, they cannot escape the effects of large-scale institutional racism, nor racism on the individual level, (e.g., racial profiling by police officers). Generally, the Black middle class, then, still identifies with being Black in America.

If identity were created through one’s personality, belief systems, personal experiences, and more, it would follow that one’s racial identity is created through how a person identifies themselves in racial terms. Helms [7] states that “racial identity actually refers to a sense of group or collective identity based on one’s perception that he or she shares a common racial heritage with a particular group” (p. 3). Black racial identity is identifying oneself as Black, sharing racial heritage, culture, and physical attributes as African Americans. Research on Black identity, or the Black experience, has often focused on the experience of inner-city Blacks living in poverty. McFarlane [6] noted that often the Black experience “is equated with poverty” (p. 164). How, then, does a Black child raised in the world of white privilege develop a Black identity?

Since the popular research focus of Black identity is on Blacks with low socioeconomic status, much has been written about the so-called culture of poverty. Focusing on a group identity that develops at the intersection of race and class, the culture of poverty refers to the perceived and stereotypical traditions and values of the poor. The term was coined by Oscar Lewis in 1959 [8]. Lewis, who researched poverty in Mexico, claimed to notice a subculture of people living in poverty. Moynihan [9], concerned with the plight of Black society, described the culture of poverty as a “tangle of pathology” created by centuries of injustices that resulted in “deep-seated structural distortions in the life of the Negro American” (p. 10). Moynihan’s [9] tangled pathology included perceived stereotypes like female-headed households, delinquency, and crime. He concluded that poverty and racism have created a culture of welfare dependency and a breakdown in family structure. He contended that generations of children raised in the culture of poverty (rather than in the culture of racism) create more generations raised with the same, again so-called, values and traditions. Following Moynihan’s beliefs is the idea that this culture of poverty is fundamental in shaping the racial identity of working class and working poor Blacks. How does Black identity being associated to the culture of poverty (rather than the culture of racism) affect the identity development of middle-class Blacks?

While there has been interest in longitudinal studies of individuals’ racial identity development in order to document change over time [10,11,12], there has not been research on how the racial identity development of affluent African Americans may be affected by the stereotyped and highly documented culture of poverty. Cross [13] stated that the purpose for studying Black identity is “to clarify and expand the discourse on Blackness by paying attention to the variability and diversity of Blackness” (p. 223). Included in Black diversity are socioeconomic differences. Although Cross’ Black Racial Identity Development (BRID) model has been tested and studied extensively, no study has been conducted using social class as a predictor. Does a person’s social class effect the development of their racial identity?

4. Operational Definitions

4.1. Class

There are two ideals that are often intermingled within the term ‘class.’ The first is the economic or material basis of class, and the second refers to social class, socioeconomic status (SES), or the actual or perceived cultural practices of class [14]. When the US society portrays the Black experience or a collective Black identity it is too often reduced to the cultural practices of class, and stereotypically so. Cole & Omari [14] describe this Black experience as “styles of dress and social conduct, and aesthetic preferences (e.g., in music) influenced by Black youth culture” (p. 788). Today, this social and cultural practice of class is often limited to, and stereotyped as, talking “loud,” speaking in the African American vernacular more commonly known as Ebonics, and wearing pants low. It is even often extended to mean “gangsta,” “thug,” or criminal-minded behaviors. In this study, class represents the economic and achievement range that a person or their family falls within. Class and SES are closely related, but SES is often assumed to lack the achievement piece.

4.2. Culture

Meriam Webster [15] defines culture as “the customary beliefs, social forms, and material traits of a racial, religious, or social group” (para. 1). This study refers to Black culture as the norms and shared experiences of Black Americans. Black culture will be generalized throughout this piece, and to include the spectrum of socioeconomic classes, but will also be dissected to examine the effect of the so-called culture of poverty (unpacked through the culture of racism) on the experience of Black culture among affluent Black Americans.

4.3. Race

While race is a social construct, it acts, in society, as a human selection of attributes based on physical characteristics like skin color, hair type, and other physical features. These attributes are often stratified as “good” or “bad” and ultimately used to discriminate.

4.4. Transracial

For the purpose of this study as it is one individual’s experience, transracial will refer to an experience of African American and white American; specifically, transracial is used to describe the adoption of a Black child by a white family.

4.5. Racialized Minority

The term racialized minority is used to describe the Black experience in the United States. It takes race as a social construct one step further by highlighting the implications of race for certain minoritized groups, in this case Blacks. Racialized refers to the negative connotations, status, treatment, and stereotypes that have been associated with what it means to be Black in America.

4.6. Black and White

For the purpose of this study the terms ‘Black’ and ‘white,’ are not necessarily used to identify the color of the skin, but a cultural/racial group. White is used to represent white or European Americans (sometimes also referred to as Caucasian), and Black is used to represent those who identify as Black Americans. Both terms represent the cultural group, not just a representation of color. In addition, Black or Black American and African American will be used interchangeably.

5. Theoretical Framework

5.1. Intersectionality

Intersectionality is a method for examining the life experiences, or worldview, of a group. It is not a theory that can be empirically tested, but a lens through which experiences can be examined. Intersectionality involves looking at a phenomenon from multiple perspectives, classifications, or identities. Intersectionality will be used to study Black racial identity development through, not only the lens of race, but also social class. In addition, race and class, as identities, will be examined as they intersect with identities that result from transracial adoption. Hill Collins [16] states that “intersectionality provides an interpretive framework for thinking through how intersections of race and gender, or sexuality and class, for example, shape any group’s experience across social contexts” (p. 208). In addition, Hill Collins [16] points out that “intersectionality works better as a substantive theory (one aimed at developing principles that can be proved true or false) when applied to individual-level behavior than when documenting group experiences” (p. 207). There is a lot to consider when conducting intersectional race research, perhaps especially including how worldviews are shaped; an intersectional approach allows for deeper understanding, evaluation, and meaning.

Hill Collins [16] states that “intersectionality references the ability of social phenomena such as race, class, and gender to mutually construct one another” (p. 205). The women’s rights movement, specifically Sojourner Truth’s 1851 [17] “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech, shed light on intersectionality (through race and gender) by bringing to the forefront the differing experiences and issues of Black women and white women [18]. Issues of purely race, class, or gender are now more likely to be studied as they affect each other in the experiences of, for example, Black women versus white women and, as is the case for this study, poor Blacks versus affluent Blacks; however, these juxtapositions are not meant as simple (and, thus, false) binaries, rather simply as analytical props to surface identity complexities. Sociologists began looking at collective experiences, especially experiences of oppression, through the intersections of race/ethnicity, class, gender, immigrant status, etc. When using an intersectional framework, these “identities are defined in relation to one another” [19] (p. 303). For example, as researchers examine inequality, they consider race and class as variables that affect the division of resources within a community. Intersectionality is “the manner in which multiple aspects of identity may combine in different ways to construct social reality” [20] (p. 176).

While there are many variables, or identities, that can be a part of an intersectional framework, (e.g., race, ethnicity, class, gender, ability, age, sexual orientation, and nationality); there may be variables that play a more dominant role in life experiences. These are variables that, together, hold stronger implications for those life experiences than when examined separately. In the United States, economic issues are so deeply intertwined at the intersection of race and class that the two variables should always be examined together as they “often stand as proxy for one another” [16] (p. 209). In addition, because race is “such an overriding feature of African-American experience in the United States…it not only overshadows economic class relations for Blacks but obscures the significance of economic class within the United State in general” [16] (p. 209).

5.2. Black Racial Identity Development (BRID) or Nigrescence

During a reading group at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Cross [21] argued identity could be viewed “as a guide of your awakened state.”. People develop an identity so that they know how to behave in specific situations. Their identity guides their interactions, actions, and reactions when they are awake and conscious. Cross [13,22] refers to Black racial identity development as nigrescence, French for “the process of becoming Black” (1999, p. 157). This study of nigrescence is formally considered (in academia) to have begun in the 1960s and gave rise to some of the first qualitative studies of Black identity development. “Models on the psychology of nigrescence depicted the stages of the negro-to-Black identity transformation experienced by many Black adults in the Black Power period” [13] (p. 157). Many identity models saw identity development as a linear phenomenon; however, the BRID model, developed by Cross from his nigrescence model, looked at racial identity in a cyclical way.

Due to the ability to apply the BRID model at any point in a person’s life or any life change, and due to the undeniably overwhelming influence Cross’ theory of Black racial identity development has had on the field of BRID, I will be using the 1971 (original) and 1991 (revised) versions of the BRID. Cross [13] theory outlines five stages of Black racial identity development as follows: Pre-encounter (stage 1) depicts the identity to be changed, Encounter (stage 2) isolates the point at which the person feels compelled to change; Immersion-Emersion (stage 3) describes the vortex of identity change; and Internalization-Commitment (stages 4 and 5) describe the habituation and internalization of the new identity (pp. 158–159).

6. Summary of the Key Topic Literature

This study examines the experiences of one Black woman (the author/researcher) as she navigates through a life intersected by race and class. In order to understand this journey, a brief look at the research on transracial adoption and the intersection of race and class follows. In addition, this study looks at shifting as a coping strategy. A working definition of shifting has been included in this section so that its use in this study is clear.

6.1. Transracial Adoption

Research on transracial adoption has been conducted since the late 1960’s and has predominantly focused on the effects on children in transracially-adopted families. While this has been a focus of study for several decades, the research on it is still very limited. Studies have been conducted either to show the negative effects of, or to support, transracial adoption; however, few studies have been done to truly understand the experiences of adults who were transracially adopted. The research review that follows looks specifically at the adoptive parents’ communication about race and their integration choices, the racial identity development of Black transracial adoptees, and the effect of the intersection of transracial adoption, race, and class on Black adoptees.

6.2. Culturally Responsive Parenting in Transracial Adoption

Research on transracial adoption generally stems from the debate on whether it is psychologically harmful to the adoptee when white families adopt other-race children. It is believed that it us up to the white parents to create an environment in which the adoptee can thrive. The following literature discusses this belief.

Lee’s [23] manuscript, The Transracial Adoption Paradox: History, Research, and Counseling Implications of Cultural Socialization, looks at the opportunities and challenges of transracial adoption families. Lee [23] found that it is imperative for adoptive parents to embrace the cultural differences within their transracial family. Those who do are “more likely to engage in enculturation and racial inoculation parenting strategies, which in turn, may contribute to more positive racial/ethnic identity development and mental health” (p. 10). In contrast, Lee found that parents who claim to be colorblind, or who deny any cultural differences, have a greater chance of raising adopted children with poor mental health.

Following this idea of deliberate culturally relevant parenting, Hamilton, Samek, Keyes, McGue, and Iacono [24] studied the identity development of transracial and same-race adoptees and focused on parent and child “communication about race and ethnicity as an element of identity development” (p. 221). Their study found that there was little to no difference in the identity development and adjustment of same-race and transracial adoptees, but that transracial adoptees and their parents had a markedly higher level of communication, with adoptive parents of Black transracial adoptees “reporting the highest level of racial/ethnic communication” [24] (p. 223). This suggests that it is inherently natural for parents of transracial adoptees to not only embrace their cultural/racial/ethnic differences, but to also openly communicate with their children about them. This leads the next body of literature, which focuses on how transracial adoptees develop their racial identity.

6.3. Racial Identity Development in Transracial Adoptees

In an ABC News documentary one Black transracial adoptee articulated his Black identity development this way, “In my teens, I became hungry to be a part of some kind of Black community, Black identity” [25] (para. 8). He was describing consciousness associated with the beginnings of the Encounter stage of nigrescence. However, the literature on transracial adoptees’ racial identity development does not use identity theory models, and, thus, does not paint a clear picture of how transracial adoptees experience identity development. Lee [23] found that while most literature finds transracial adoptees as ‘well-adjusted,’ it fails to “unravel the specific factors that affect cultural socialization, racial/ethnic identity development, and psychological adjustment” (p. 13). He addresses researchers by stating that they “must do a better job at understanding transracial adoptees as active agents of change in their lives,” by specifically examining “how adoptees personally negotiate their identities and sense of place in society” (p. 11).

6.4. The Intersection of Race and Class and the Transracial Adoptee

Butler-Sweet’s [26] article, “‘Acting White’ and ‘Acting Black’: Exploring Transracial Adoption, Middle-Class Families, and Racial Socialization,” reviews the sparse research on the intersection of race and class as it pertains to transracial adoptees. She concludes her review with an examination of transracial adoption in which she notes, “how middle-class status, along with the experience of growing up in…transracial families, shapes dynamics of Black identity” (p. 210). The theme that seemed interwoven throughout this article is a presumption by white adoptive parents that Black culture is deficit, a culture of poverty, and, thus, inextricably linked to the idea that racial identity is also classed. The belief that Black culture is inner city culture is an idea that is prevalent in the media, therefore it is not surprising that white parents, with little exposure to Black families, would adopt this idea. However, Black families exist across class contexts, in the United States and around the world. Even Black middle-class families often belong to Black social clubs, like “Jack and Jill,” which surround middle-class Black children with other middle-class Black children. White transracial adoptive parents lack knowledge about, and, perhaps, access to, these types of groups, and thus lack access to middle-class Black families. Study respondents in Butler-Sweet’s review recalled pressure to be highly educated and extremely articulate, and being in social and educational situations where they were often the only Black person and, thus, were tasked by their parents to not represent any stereotypical Black characteristics, specifically around speech. One respondent stated that his parent would say, “you’re Black, and people have assumptions about you just because of that, so you need to prove them wrong” [26] (p. 198). This led to the adoptees being “accused of ‘acting white’ because they were, in fact, ‘acting middle class’” (p. 199). Butler-Sweet concludes by stating that the intersection of race and class has a large impact on transracial adoptees, and that “racial identity literature rarely explores the impact of class. Moreover, the body of research on transracial adoption ignores class all together” (p. 211).

6.5. The Intersection of Race and Class and the Effect on Identity Development

As noted previously, a person develops an identity so he/she knows how to behave in situations. This identity guides a person’s awake and conscious interactions, actions, and reactions [21]. It would follow that one’s racial identity is how a person identifies him/herself in racial terms. Again, as discussed earlier, Helms [7] argues that “racial identity actually refers to a sense of group or collective identity based on one’s perception that he or she shares a common racial heritage with a particular group” (p. 3). Black racial identity is identifying oneself as Black, sharing racial heritage, culture, and physical attributes as African Americans.

Similar to intersectionality, nigrescence theory should be used as a lens “through which to view the historical reality” of Black Americans [27] (p. 162). Parham stresses that when studying nigrescence it is imperative to consider the social context. “It is important to view the social circumstances that instigate the cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and spiritual reactions people exhibit” (p. 163). Parham states that when the social context is positive and supportive, then a positive racial identity should develop. However, if the social context is full of the negative experiences of racism and discrimination, then the development of a person’s racial identity will be “an adequate reflection of that person’s struggle for identity congruence. Remember that nigrescence is a process that addresses the development of identity within the context of social oppression” (p. 163). Is it reasonable to presume, then, that affluent Blacks who have managed to find a positive space in mainstream American society will not have the same negative experiences as poor Blacks who may face racism and discrimination on a more oppressive level?

It is imperative to study experiences of racism through the intersection of race and class within a race-charged society like the United States. It is at this intersection that we see how deep and disturbing race relations are in the United States. Feagin and Sikes [28] discuss the experiences of racism on the Black middle-class. They state that even the Black middle-class experience racism as a daily occurrence. These experiences are “lived experiences” that not only cause mental pain and stress, but also have a cumulative effect that “significantly affects a Black person’s behavior and understanding of life (p. 17). “The daily experiences of racial hostility and discrimination encountered by middle-class and other African Americans are the constituent elements of the interlocking social structures and processes called institutionalized racism” [28] (p. 17, emphasis original). In addition, the authors state that racist interactions between middle-class Blacks and whites have dimensions that include the site of the action, (i.e., predominantly white workplace, public places like restaurants, public places with great exposure like parks, and traditionally white spaces); the range of discriminatory action, (i.e., insults, insensitivities, avoidance, exclusion and rejection, verbal attacks/slurs, and physical harm); the impact on the victim (“discrimination is an energy-consuming, life-consuming experience” [28] (p. 23) leading to determination, embarrassment, frustration, bitterness, anger, range, and more with any mix of more than one reaction); and the coping mechanism, (i.e., flight, ignore, confront—all after evaluating the situation, or reexamining the situation). The authors study the Black middle-class because of their frequent interactions with whites. The Black middle-class “are often the ones who are desegregating historically white arenas and institutions, including upscale restaurants and department stores, business enterprises, corporate and government workplaces, white colleges, and white neighborhoods” [28] (p. 26). What kind of racial identity develops when a Black person is afforded some of the privilege of being on a higher socioeconomic level, but lives within a society of institutionalized racism and what Bonilla-Silva [29] refers to as colorblind racism, which negates the importance of race in a racially charged society by stressing rhetoric of equality?

In Assimilation Blues: Black Families in White Communities. Who Succeeds and Why?, Tatum [30] also uses intersectionality to research the life experiences of middle-class (class) Black (race) families (life choice) living in predominantly white (race) middle-class (class) communities (life choice). Tatum set out to answer the question “What does it mean to be a middle-class Black parent living, working, and raising children in the midst of a predominantly white community?” (p. 4). Using intersectionality as a lens, Tatum discovered that middle-class Black families use their own network of religion, family and friends in order to stay grounded within their own Black identity. They learn to ‘play the game’ or navigate in the white community by understanding and mastering the rules of engagement even when those rules differ greatly from Black community rules. Finally, Tatum reported that there was an ever-present collective belief about the long-term benefits of living within the white community that kept the Black families there even when they had doubts. Intersectionality allowed Tatum to uncover a collective worldview of Black, middle-class parents living in predominantly white, middle-class communities. How does this collective worldview, or identity, differ from that of working class and working poor Blacks living in segregated inner-cities?

Tatum [30] studied Black middle-class families living in a predominantly white community. However, many Black middle-class families live in segregated Black communities [31]. Pattillo-McCoy researched the segregation of the Black middle-class on Chicago’s South Side claiming that middle-class African Americans “are an overlooked population still rooted in the contemporary Black Belts of cities across the country” (p. 4, emphasis original). Pattillo-McCoy notes further that the media portrayal of ‘gangster life’ through movies and music, and the proximity of these segregated middle-class Black neighborhoods to working class or working poor Black neighborhoods, often finds Black middle-class youth in “downward mobilization” that may lead them to join gangs and engage in criminal activity (p. 7). Pattillo-McCoy argues that Black middle-class youth in these spaces may develop their identities from negative popular culture; that their segregation from economic and race privilege and interactions with the culture of violence codified as the culture of poverty can lead them to make negative choices. Pattillo-McCoy describes Black residential segregation further by explaining that the South Side of Chicago not only has all-Black housing projects and middle-class Black neighborhoods like the one she studied, but it also is the location of mansions owned by affluent Blacks including Muhammad Ali, Jesse Jackson, and Louis Farrakhan, among others. It is important to note that all three of these affluent Black men are known for their strong Black identities, no doubt a factor in their neighborhood choice.

As mentioned previously, there are two ideals intermingled within the term ‘class.’ The first is the economic or material basis of class, and the second refers to social class, or the cultural practices of class [14]. Discussion of the economic basis of class has figured prominently in my discussion in this article thus far, but I have only hinted at the cultural practices of class. When the Black experience or a collective Black identity is discussed in society, it is often referred to only through references to the cultural practices of class. As noted earlier, Cole and Omari [14] described the Black experience as “styles of dress and social conduct, and aesthetic preferences, (e.g., in music) influenced by Black youth culture” (p. 788). The extent to which middle-class and affluent African Americans navigate these social and cultural practices of class as part of the Black experience or their own identity is not examined.

6.6. Shifting

Shifting is a coping strategy used to help people fit in to the culture that is dominant in any given environment. However, shifting is most commonly associated with the tendency for minoritized people to shift their behavior and thinking to reflect that of the majority white economically privileged. When people shift, they “change the way they think of things or the expectation they have for themselves. Or they alter their outer appearance. They modify their speech. They shift in one direction at work each morning, then in another at home each night. They adjust the way they act in one context after another” [1] (p. 61).

7. Methodology

7.1. Restatement of the Purpose

The purpose of this reflective, autoethnographic qualitative case study is to extend and personalize my past research on Black teachers working in predominantly white private schools. This study details my experiences and journey to self-acceptance using intersectional analysis to highlight the effects of race and class as it pertains to my transracial adoptee status. In addition, this study details my Black racial identity development as theorized by Cross [13]. My hope is that this study may influence the ways that we, as a Black community (and larger society), think about the intersection of race and class and the ways in which our unique lived experiences effect our identity development. I also hope that my specific story will help Black individuals (and others) struggling with their personal, academic, and professional identities by sharing with them coping skills and techniques that may lead them to self-discovery, and ultimately, self-acceptance.

7.2. Research Questions

This study is based on two main and three ancillary research questions aimed at providing greater understanding of the author/researcher’s journey through racial identity development to self-acceptance. This includes the coping strategies developed and support systems activated.

The two main research questions this study engages are: (1) How did the author/researcher develop her Black identity as a transracial adoptee living at the intersection of race and class; and, (2) What was the author/researcher’s journey towards her present state of racial self-acceptance and understanding? Three ancillary research questions are also engaged: (a) How did social and societal factors influence the author/researcher’s racial identity development? (b) How did the author/researcher build a support network or personal and professional community? and, (c) How was the author/researcher able to get to a place near self-love?

7.3. Approach to the Study

Current research in the field of racial identity as being conducted primarily using qualitative inquiry. Qualitative studies allow the researcher insight into an individual case or a phenomenon [32]. The qualitative study offers a human understanding of experiences and thinking of participants in a study [32]. This insight is necessary in studies like this one that aim to understand the experiences, coping strategies and identity development of an individual. To accomplish this goal, I chose a reflective biographical (autoethnographic) qualitative study design. This reflective qualitative study employed a single-case study model. The case study considers the phenomenon, which in this case is the racial identity experience of a Black transracial adoptee, in context, the context being the predominantly white and affluent family and community [32]. This study was conducted with the author as the researcher and the participant, relying heavily on self-reflection, which I aligned to theory. This study is a continuation of my dissertation research [33], which examined the experiences of Black teachers working in predominantly white and affluent private schools. One of the findings from that study was that all but one of the subjects grew-up in and/or were educated in predominantly white and affluent communities and/or schools, and this influenced their professional trajectories as adults. Following this finding, my purpose for this piece was to examine my own life experiences and choices using intersectional analysis [16] in tandem with Cross’ [13] BRID model.

7.4. Data Collection

As I was the research participant and researcher for this study, I used a hybrid inquiry-evaluation process of self-reflection and critical analysis to access (from my memory) and review (from written archives) the key factors in my racial identity development that have brought me to where I am today. My goal was to determine the time periods in my life that were the most salient to my development. I created identity charts for each time period identified, in concert with reviewing self-reflective academic coursework and responding to standard journal prompts. Finally, I wrote letters to my younger selves to reflect on how I felt and what I did/did not do to cope during those times.

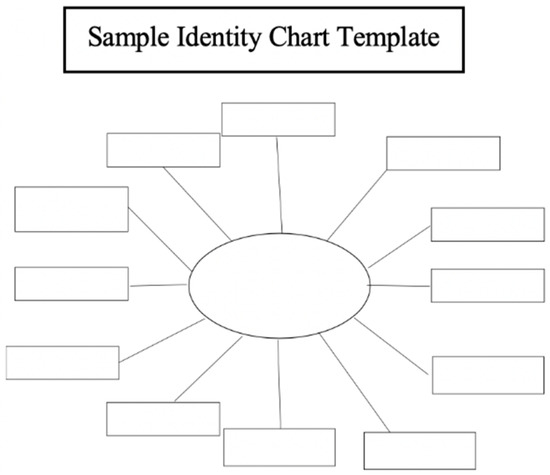

7.4.1. Time Period Identity Charts

I developed a typical identity chart template like those used in many identity development workshops (see Figure 1, below). For each chart, in the center I added a time period that represented a time in my life. The earlier time period charts are organized around a place my family lived, but with the later time period charts it made more sense to organize them around my places of employment. After I designated the time periods, I took time to reflect on what was going on in my life at each period and filled out the outer boxes with identity traits and inner feelings that represented who I was and what I was experiencing at that time.

Figure 1.

Identity chart template.

My time periods were distributed as follows, beginning when I was six years old as I do not remember much prior to that time: Egypt 1977–1980, Miami 1980–1985, Towson HS 1985–1986, WLHS 1986–1989, College Park 1989–1991, Towson U 1991–1994, Neo-Professional 1995–2001, Japan 2001–2003, Celebree 2003–2006, SA 1 2006–2008, Bright Horizons 2008–2009, UNLV 2009–2013, BASIS SA 2013–2017, TNTP 2017–2018, present day.

7.4.2. Archived Self-analysis Documents

I looked through old computer files to find work I had completed on identity development or any kind of self-analysis. I found three documents, detailed below, which I used to evaluate differences in my thinking then-to-now, as well as to align similarities to surface thought constants in my self-awareness and/or reflection, particularly as these relate to my life experiences, choices, and education.

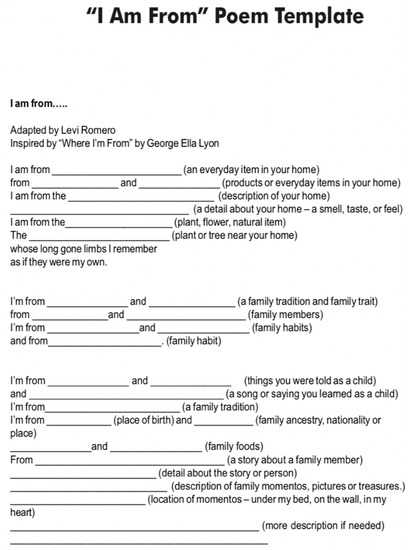

I AM FROM poem written in stages between 1996–2003. I AM FROM poems are built using the sentence stem, “I am from…” They are an adapted version poet George Ella Lyon’s [34] “Where I’m From” poem. Figure 2, below, illustrates one way to scaffold the development of an I AM FROM poem.

Figure 2.

Example of an I AM FROM poem developmental scaffold.

As with the identity chart template, many “diversity” education workshops have participants write these poems as a way of reflecting on their childhood, adolescent, and adult life, and then share those reflections within a larger group as to reveal common experiences with others who may look very different, as well as divergent experiences with those who look more similar. I began writing my I AM FROM poem in 1996, and have returned to refine/augment it several times since then, most recently in 2003. Similar to my self-analysis with the identity charts, I examined differences in my sense of “being from” from one iteration to the next, as well as constants in this sense from the first to the most current iteration.

Cultural Self-analysis Paper for Spring 2010 Multicultural Education Course

In the Spring of 2010, I wrote a cultural self-analysis paper for CIG 660: Multicultural Education that documented my cultural values and their origins. In the paper I explored my cultural rituals and ceremonies, value in work and leisure, belief about education, roles, and status, and use of names and forms of address. Specifically, I answered the following questions: How did/do you show respect to older people, younger people, or authority figures? What is the purpose of play? What is a vacation? What methods of teaching and learning occurs/ed in your home? What was/is commonly taught? What tasks do you expect to be performed by girls, and what tasks by boys? Do names change in any way of the course of someone’s lifetime?

On the inside, Looking out Assignment for Spring 2010 Multicultural Education Theory and Research Course

Additionally, in the Spring of 2010, for an assignment in CIG 662: Theory and Research in Multicultural Education, I wrote a personal narrative focusing on my outsider within [35] experience. The narrative chronicles my life experiences that led to my feeling ‘minoritized’ and like an ‘outsider within’ my own family, school, and community; the narrative also discusses how, concomitantly with choices I made in college and in work, this feeling led me to my later-in-life personal, academic, and professional successes.

7.4.3. Journal Prompts and Responses

Journaling “removes mental blocks and allows you to use all of your brainpower to better understand yourself, others and the world around you” [36] (para. 6). For this reason, while working on my identity charts, I chose to journal, using standard journal prompts, to dive deeper into who I was at during each time period. Accordingly, the journal prompts helped me to extend and deepen my self-discovery beyond what the charts themselves required. I used the same questions for every journal entry: What do you need right now? What do people not know about you? What is your biggest fear? What makes you happy? What are you most proud of? What do you wish you could change? What is the most important thing to you? What significant choices did you make and why? Who are the important people in your life and what roles do they play? Once again, the journals allowed me to document, in greater detail, the thoughts, feelings, and beliefs I held that changed and that stayed more-or-less the same over time.

7.4.4. Letters to My Younger Self

The final piece of data I developed involved writing unstructured letters to my younger selves. While completing the identity charts and journal prompts there were some very difficult memories and emotions that surfaced. In order to best engage those emotions and understand how they impacted my life choices, I wrote letters of advice and support to my younger self, one for each most difficult memory/emotion, typically aligned with the time periods on my identity charts. Through these letters I was able to identify the experience, knowledge, and support that were missing in my life that would either have made the time period less traumatic, and/or would have helped me to resolve them better or sooner.

7.5. Data Analysis and Data Interpretation

The data analysis was conducted using triangulation of the identity charts, journal entries, archived documents, and letters to my younger selves. Triangulation is used to cross-examine multiple types of data [37]. The identity charts guided my data analysis as they were the most concise and, thus, easiest to compare with each other. From the charts I found many sub-themes emerges. I used these sub-themes to analyze the other sources of data to look for similarities and differences across time spans. Specifically, I looked for similar themes around identity development, emotions, support systems, education, race, and class. I used these analyses to identify four main themes: (1) Awareness of inequity and discrimination; (2) the never-ending pursuit of knowledge; (3) the importance of developing a peer support network; and, (4) comfort in emphasizing what makes me different.

8. Findings

Someone interviewing me for a fellowship once called me exhausting; this is ironic because both my personality and energy level are extremely laid back! I have been accused of being unemotional, reserved, unapproachable, aloof, but exhausting was never a word anyone had used to describe me before that interview. The interviewer and I were simply chatting about my life and work experiences that led me to what I believe about education, diversity, and equity, among other similar topics. That’s when she called me exhausting! The crazy part for me was that she knew less than a quarter of my story, and she already called me exhausting! I thought, “Lady, if you only knew!” To begin this reflective piece, I asked myself two main research questions: (1) How did I develop my Black identity as a transracial adoptee living at the intersection of race and class; and, (2) What was my journey towards my present state of racial self-acceptance and understanding? I also asked myself three ancillary research questions: (a) How did social and societal factors influence my racial identity development? (b) How did I build a support network or personal and professional community? and, (c) How was I able to get to a place near self-love?

My journey from transracial adoptee to self-acceptance as a mature adult was long, and at times, difficult. I found myself in a constant state of ‘otherness,’ not really fitting in anywhere. I was exposed to a different side of discrimination and racism as a pseudo insider. As I discussed in my cultural self-analysis paper, I was ‘white by association,’ and, thus, I was privy to a view of discrimination that most minoritized individuals do not ever see. Because of this precarious situation, I was forced to devise strategies to cope as I navigated my space in the world.

As I analyzed the data I collected and created, I noted that the main four themes that emerged in my self-reflections paralleled that arose in my original dissertation research. In addition to examining these themes, I noticed that my process of nigrescence, based on Cross’ [13] theory of Black racial identity development, could be chronicled as it was for the participants in my original doctoral research [33].

The first theme from my self-reflection involved intersectionality. Race and class, and all the ramifications of the intersection of the two, hung over me from birth. However, it was the specific ways in which elitism, racism, and discrimination were purposefully illuminated to me by my adoptive mother from a very young age that led to my intersectional awareness of inequity and discrimination. Ironically, perhaps, mother referred to this awareness as “calling a spade a spade.”. She pointed out the isms, how people were attempting to use them to define or restrict me, and the negative messages about myself and my race that came with the isms that I should not buy into. Because of this socialization, ‘being woke’ became a way of life for me long before it was a catch phrase. This theme parallels my dissertation work in which the respondents reported experiencing tokenism daily as a result of working at the intersection of race (being Black at predominantly white institutions) and the culture of poverty stereotype associated with being Black assumed by whites in the affluent communities in which they worked.

The second theme involved the absolute belief in the power of knowledge and, thus, my never-ending pursuit of it. My parents instilled this in me through education and I have carried it out by adopting lifelong learning as a core value. My mother said that isms are born out of ignorance, thus I made it my mission to counter them with education. This paralleled part of the second theme in my dissertation in which my participants all reported feeling the need to overperform professionally and educationally.

The third theme emerges from the limited opportunity I had to connect with people older than me within and outside my family, the result of life circumstances (which I discuss further in a moment). Due to this lack of experience and exposure, I did not gain knowledge and guidance, or even comfort, from my elders. Instead, I developed an intricate web of a support group of peers. This forced me to look within people to see what I could learn from them, and to be deliberate when considering what role/use a person had in my life. The participants in my dissertation study all also developed a specific support network of folks who they could lean on. This support network was vital to their ability to be successful and continue their work in an environment where they were often the only minoritized person in any given room.

Finally, the fourth theme that emerged during my self-reflection was one of ‘otherness.’ I was different from my family, from my classmates, from other African Americans. There was no way around this fact. My transracial adoption and life experiences made it so. I developed a niche of playing to my difference as strength and a thing that made me relevant and a ‘cultural shape shifter’ of sorts. Similarly, my dissertation participants all described the need to create a personal mission within their professional lives. This enabled them to find comfort in their difference, making their jobs about a greater cause. I have come to refer to this difference as “my calling,’ and it was born out of my need to use my ‘otherness’ to carve out a niche professionally.

These four themes can be considered the coping mechanisms by which I developed a Black racial identity through my life, lived at the intersection of race and class, which ultimately lead me to my current state of self-acceptance and purpose. These themes will now be further examined over seven periods of my life that represent different stages of my development and which correspond with the identity charts. I label these life periods: (1) Elementary school, (2) middle school, (3) high school, (4) college, (5) neo-professional, (6) professional, and, (7) my current state of reaching self-acceptance.

9. Discussion

As I mention in the introduction, I was transracially adopted by a white family in 1971. I was the youngest of four children, the other three all biological to my adoptive parents, and consequently, all white. My parents had plans to adopt another Black child after me but were blocked by the NABSW; but they had the right instinct in this regard. They knew that it would be difficult for me to be the only minoritized person in my family; however, my mother truly believed that she could nurture me in a way that would compensate for my minoritized status. We, as a family, set off on an experiment of race and class called ‘my life.’ My dad was a college professor who was dedicated to teaching and did not want to publish. That meant that every three to five years, when it was time to perish or publish, we would move. The first move that I can remember, and that had a significant effect on my identity development, was our move to Egypt in 1977. My mother was a secondary English teacher primarily working in predominantly white and affluent private schools, and the general rule was that we attended school wherever she worked. We all attended a private American school with many “expatriates” from all over the world. (It is ironic how white Americans are called expatriates in other countries, but especially People of Color living in the United States are called “immigrants.”.) I remember feeling very American during the three years we lived in Egypt. I held everything American in high esteem: 1970s television shows like, The Love Boat and Fantasy Island, McDonald’s restaurants, and Nestle’s crisps bars. I was so tied to being an American that I complained every summer when we couldn’t afford plane tickets to go back to the States like my school friends did. They always came back to Egypt with the best snacks! Instead, my family backpacked through Europe, and spent months on the beaches in Greece. While I am now so thankful for those experiences, at the time I felt so deprived! Additionally because the school was so culturally diverse, I don’t ever remember feeling different around my friends. However, I do remember the very first time that I recognized that others saw me as different from my family. We were on a bus tour to the pyramids and, as I got off the bus, a Nubian woman grabbed me. She must have thought I was a stow away bothering the American tourists! My mother jumped to my defense, and later explained the mistake to me. It would be one of many conversations that we would have about race and others’ feelings about my race and my place in our family. Cross [13] would describe my identity during this period as Pre-encounter. This is the identity that will be changed by “encounters.”.

9.1. Becoming ‘Woke’

“Let us not look back in anger, nor forward in fear, but around in awareness.”—James Thurber [38] (para. 1)

We left Egypt in 1980 and moved to Miami, Florida. My oldest brother had graduated high school in Egypt and was off to Georgetown after a gap year traveling with friends in Europe. My mom got a job at a prestigious school in an affluent suburb of Miami, and my siblings and I were enrolled in school there. While the socioeconomics of the school in Egypt and the one in Miami were very similar, the diversity was not. For the first few years I was the only Black person in my grade. Eventually, a girl who was mixed (Black and white), but who identified mostly as white, and a Hattian girl joined my grade, but I was still the only African American in my grade. My friends were not only predominantly white, but also lived much different lives than me. They lived in large houses, vacationed at Club Med, wore designer jeans, and were members of elite country clubs. This country club membership became a constant theme of inequity for me as a middle schooler. It began with an innocent invitation to go swimming. One of my closest friends casually invited me to go with her to the pool at her family’s club. It didn’t seem like a big deal to me as I had been swimming at a few embassies in Egypt. I went home and told my mom. Later that night my mom sat me down and told me that I had been uninvited to swim because the country club was segregated and did not allow Blacks to swim there. She continued by saying that my friend was welcome at our house any time, but that I would no longer be allowed to go to her house as long as her parents were members at a club that discriminated against people based solely on the color of their skin. My mom was great that way. She always called other people’s racism out to me and explained to me that it said something about their character, but it meant nothing to mine. I attended countless Bar and Bat Mitzvahs and, when I did, my mom always noted that I was a trailblazer as I was often the first Black person to attend a party at some of the venues where they were held.

Ironically, as I matured, I realized that my mom also held some prejudiced views, mainly related to race and class. She often spoke negatively about friends of mine who spoke with “broken English.”. When my ex-husband’s coat was stolen from his car at a mall, my mom asked my friend who lived in housing projects to “keep an eye out” for the coat in his neighborhood. Once, in a heated argument, my mom told me that when she adopted me she had believed in nurture over nature, but that maybe she was wrong. I never asked her to explain, but I understood her to mean that she was not able to keep me from “becoming Black.”. This experience marks my movement into the Encounter stage in the Cross model. It was at that moment that I realized there was more to my identity than I was aware. While my mom raised me to acknowledge racism when I saw it, that argument changed how I saw my mom, which, in turn, allowed me to break free from her to explore my identity as a Black woman. My mom made it a point to always acknowledge my race, but not my racial identity. She saw educated, affluent, successful Black people simply as ‘darker white folks;’ no different from her in any way other than skin color.

In Miami, I began dating a Black Jamaican boy and, in integrating into his family, I realized that there was a culture that I had not been privy to, and I wanted more. In 1985 we moved to a suburb of Baltimore, Maryland. I was the only child left at home. My mom gave me the opportunity to either go to the local public high school or to enroll in the private all-girls Catholic school where she would be teaching. I chose to enroll in public school because I wanted to be around other Black students for the first time in my life. This decision marks my entrance into Cross’s Immersion-Emersion. During high school my friends were predominantly Black, I listened exclusively to R&B and rap music, I learned to codeswitch to urban slang, and I changed my style of dress to represent the youth culture to which I was adapting. However, while I was beginning to develop a Black identity, I was also introduced to inequity in education in a shocking way.

9.2. Becoming a Lifelong Learner

“Education is not preparation for life; education is life itself.”—John Dewey [39] (p. 239)

As earlier discussed, education was always a priority in my family; my siblings and I attended rigorous private schools, my mom was an educator with a master’s degree, and my dad was a professor with a doctorate. When I entered ninth grade, I had two siblings at Georgetown University, and one at Johns Hopkins University. I always believed that I was smart and entitled to a top-notch education. The day that we enrolled in the local public school my mom came loaded with my previous coursework that included Latin, French, and Algebra 1, all in middle school. She insisted that I be put in the most rigorous courses. I was excited for public school, and a more diverse experience, but what I found was inequity, institutional racism, and segregation. I was the only African American in my honors classes. I met Black friends in choir, gym, and lunch, but they were not in any of my core courses. I know that these friends were at least as smart as me, if not smarter, and I could not understand why they were not afforded the same course opportunities as me. The only difference I could see between them and me was that most of them were economically disadvantaged, whereas the white students and I were predominantly affluent. It was my first introduction to educational inequity, and the intersection of race and class in the educational setting. I only attended that school for one year. My parents moved to a truly integrated community the next year, and I completed high school there. However, this experience in my freshman year stuck with me. It ultimately motivated me to dedicate my career to creating diverse, rigorous education experiences that are equitable and, most importantly, accessible to all students, especially Black students. It made me cherish education and seek it out at all costs for myself and for my children. It made me vow to never stop learning because it is a privilege that is not distributed evenly in our country.

Although the quality of my public school experience got better after my freshman year in high school, I still was unable to link my educational persona to my cultural persona. I did not have any Teachers of Color during my entire K-12 experience, thus my peers were my cultural guides; I did not have, and had never had, any mentors nor any adult role models.

9.3. Establishing a ‘Band of Brothers and Sisters’

“Mentoring is a brain to pick, an ear to listen, and a push in the right direction.”—John C. Crosby [40] (para. 1)

As I entered college, majored in African American studies and sociology, and joined the Black Student Union, I entered what Cross calls Internalization. During college my friends were exclusively Black and they were my world. At this point I did not feel like my adoptive family knew me at all. My mom dismissed everything culturally Black about me, and my siblings, who had not lived with me since I was a middle schooler, seemed distant. I developed a support group of Black friends from whom I learned everything about how to navigate the world. Since we had moved around so much and I didn’t have any adult role models, my support group consisted of friends around my age. I learned quickly how to form a supportive circle that was tight-knit and met my emotional and cultural needs. It was not until forming my dissertation committee that I had my first true mentor.

I remained in Internalization for most of my young adult life. I surrounded myself with people who were pro-Black within the educational community. I was an independent school diversity coordinator and I conducted workshops on diversity within private schools. I served on national diversity committees and immersed myself in the Black private school community. However, my second international experience made me look at who I was and who I wanted to be, and ultimately is responsible for bringing me through Internalization and to what I call self-acceptance.

While working as a school administrator, I took two classes in pursuit of a doctorate program. Then, I married an African American man who was a United States Air Force officer and moved to Japan. I gave up the job and school and immediately became “the spouse.”. As a military spouse your identity is consumed by your spouses’ rank and job. The first thing anyone on base asks you is, “What rank is your husband, and what does he do?” I was an accomplished professional with a graduate degree, but, instantaneously, felt like I didn’t matter. Since we lived on base in a small fishing village in Japan, my life soon came to revolve around my husband, then my children, and “pampered chef parties.”. I was expected to associate exclusively with other officers’ wives; not surprisingly, perhaps, there are far fewer Black officers than white. Still, I embraced this role for the eighteen months that we lived in Japan and was able to form friendships with women of all colors. We bonded over lunches, our children, and our shared perceived loss of identity as “wives.”. Ironically, this is when I began to look at myself as more than a Black woman—confined to race and gender. It was the first time in my adult life when I was seen first as a spouse, a mom, a friend, and my race especially seemed to be almost a non-factor. Similar to my early days in Egypt, our shared American identity bonded us. When we returned to the United States, I had a stronger sense of my whole identity. I began working in educational leadership and learned to find allies of all races who were aligned with my core values.

Professionally, my core value is “whatever is in the best interest of children.”. I began to look at equity through the lens of intersectionality: Equity works best when all students, across race, class, other dimensions social identity, past personal experiences, among many other characteristics have access to rigorous education that meets their diverse needs. In order to attain this lofty goal, I embrace everyone and anyone who shares this belief. I spent many years in Maryland and San Antonio developing a supportive peer network, while honing my leadership skills and creating my professional identity.

9.4. Play to My Differences

“Find out who you are and do it on purpose.”—Dolly Parton [41] (para. 1)

In 2009, the military moved us to Las Vegas, Nevada. My children were now all school-aged, so I decided to enroll in a doctorate program full-time. I knew that I wanted to focus my research on my experiences. I chose to focus all of my research on the experiences of Black teachers working in predominantly white and affluent private schools. I wanted to find out if my experiences of tokenism were universal for Black teachers. I wanted to better understand how Black people in predominantly white environments maintain and develop their racial identity. I wanted to see what coping mechanisms Black teachers used in order to be successful in an environment where they were ‘the only one.’ I recognized that my unique experiences, my otherness, afforded me a lens to examine racial identity development and class in a way that has mostly been ignored.

I have found that when I ‘lean in’ to what makes me different, I discover what makes me relevant. It is my experiences as ‘other’ that make me relatable to almost anyone. In addition, embracing my identity and experiences in this way allows me to not only be relatable, but it allows me to relate and connect in a way that I had not previously. It was at this point in my life that I was able to bond with my first true mentor. I was able to look at someone who was experienced and accomplished and truly see through her eyes that she truly saw me and understood me. As a result of her support and guidance, I was able to understand my path and my ‘calling.’

As a child I used my ‘otherness’ to gain certain privileges. In eighth grade I was the only middle schooler allowed to run track with high school. I was a really good athlete, but I was also, coincidentally, the only Black person in eighth grade at my school. I believe, but cannot prove, that some stereotypes about athletic prowess motivated the coach to ask for me. I did not have any standing times or running résumé as the school did not have a middle school track team.

As a neo-professional working in predominantly white and affluent schools, I played to my ‘otherness’ to carve out a niche for myself. Diversity was the buzzword, and I was an ‘acceptable’ Black person who had traveled the world, read the classics, learned how to mingle with ‘old money.’ I used these experiences to my advantage to gain access to the elite community where I tried to, not only open minds, but also be a support to the Students of Color and to open doors for more Teachers of Color. At that time, I was comfortable being the token minoritized person. I am no longer comfortable being used in that space, but still use my ‘otherness’ as life experiences that set me apart professionally, and make me uniquely qualified to offer specific developing, coaching, and training for school leaders

This road to self-acceptance has been long and full of detours and back peddling; but on this journey I have learned that my strongest assets are my wide range of experiences, my depth of knowledge, my core beliefs and a strong identity, and my comfort in playing to what makes me different. I no longer am comfortable accepting what is, at best, conditional privilege based on racial stereotypes or token status, but I do see my unique circumstances as a way to stand out.

10. Conclusions

I originally set out on this reflective journey to see if my racial identity development and professional experiences were similar to those among my participants in my doctoral dissertation research. In addition, I wanted to determine how my transracial adoption affected my identity development. I chose two main research questions to explore: (1) How did the author/researcher develop her Black identity as a transracial adoptee living at the intersection of race and class; and, (2) What was the author/researcher’s journey towards her present state of racial self-acceptance and understanding? I also chose three ancillary research questions to explore: (a) How did social and societal factors influence the author/researcher’s racial identity development? (b) How did the author/researcher build a support network or personal and professional community? and, (c) How was the author/researcher able to get to a place near self-love? In seeking answers to these questions, I found that my racial identity, like the identities of the participants in my original study, did align with Cross’ nigrescence model. Additionally, in seeking answers to these questions, I uncovered four major themes that spanned across my lifetime which also corresponded to themes derived from the experiences of my dissertation research participants: (1) Awareness of inequity and discrimination; (2) the never-ending pursuit of knowledge; (3) comfort in emphasizing what makes me different; and, (4) the importance of developing a peer support network. While these themes were apparent in my research, as I have come to a place of self-love and have found my ‘calling,’ I have developed within each theme over time.

Developing within the first theme, my being ‘woke’ has resulted in my relentless drive to no longer be seen as a token. It is imperative for me to view educational policies and practices through a lens of equity and access so that all children, regardless of race or socioeconomic status, have access to a rigorous education that fits their learning needs. I no longer view the established white and affluent school and curriculum as the best. My decisions as a former administrator and as a parent are no longer influenced by race and class, but by what is in the best interest of children.

Developing within the second theme, as a child of educators, learning has always been a priority. However, I have made lifelong learning my passion. Seeing my parents achieve high levels of education, but also seeing their beliefs stay stagnate through changing times, I have made it my passion to never stop learning and to never stop challenging my own beliefs and knowledge bases. In addition, I value the knowledge I gain from others through mentoring and being mentored in a way that I was not introduced to as a child.

These mentorship and mentoring relationships are a crucial part of my development within the third theme: Support networks. While I have learned to pull others up and to reach across and grow with friends and colleagues, the greatest asset to my personal and professional growth came from learning to reach up to those who can guide, teach, and support me. In my letters to my younger self there was a persistent theme of wishing that I had someone to guide me through traumatic experiences and life decisions. I now look for people who can offer this relationship to me, and I make a conscious effort to be that person for as many people as possible.

Finally, I recognize growth in my development within the fourth theme, my ‘calling.’ What I know to be true about myself is that I am at my best when I am developing and supporting school leaders. My ability to relate to, and be relatable to, so many different kinds of people due to my unique background allows me to deeply connect with leaders and skillfully see their strengths and areas of development. My educational and professional experiences allow me to guide them in developing school cultures that meet their mission and vision while creating environments for teachers and students that are diverse, equitable, accessible, and rigorous. I have found that this support is a gap that needs to be filled specifically with the influx of charter schools within the school choice movement. I am playing to my differences by using my unique personal and professional experiences to find my niche and fill this gap, including using insight that I have gained through raced and classed intersectional experience and academic analysis. Since the work I have done in self-reflection and exploring my identity development, my job no longer feels like a job; it feels like a calling.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Jones, C.; Shorter-Gooden, K. Shifting: The Double Lives of Black Women in America; Harper Collins Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, J. No Name in the Street; Dell Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- American Heritage Dictionary. Racialized. In American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 5th ed.; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 1384–1387. [Google Scholar]

- Bremner, R.; Barnard, J.; Hareven, T.; Mennel, R. Children and Youth in America: A Documentary History (Volume 3, 1933–1973 (Parts 1–4)); Harvard University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Liem, D.; National Association of American Transracial Adoption (NAATA). Adoption History: A Brief Overview. 2000. Available online: http://archive.pov.org/firstpersonplural/history/ (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- McFarlane, A.G. Operatively White?: Exploring the Significance of Race and Class through the Paradox of Black Middle Classness. 2009. Available online: http://www.law.duke.edu/journals/lcp (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- Helms, J.E. Black and White Racial Identity: Theory, Research, and Practice; Praeger Publishers: Westport, CT, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, O. Five Families; Mexican Case Studies in the Culture of Poverty; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan, D. The Negro Family: The Case for National Action; Office of Policy Planning and Research, United States Department of Labor: Washington, DC, USA, 1965.

- Chávez, A.; Guido-DiBrito, F. Racial and ethnic identity and development. In New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education; Ross-Gordon, J.M., Coryell, J.E., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999; pp. 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, W.E., Jr.; Fhagen-Smith, P. Patterns of African American identity development: A life span perspective. In New Perspectives on Racial Identity: A Theoretical and Practical Anthology; Wijeyesinghe, C., Jackson, B.W., Eds.; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 243–270. [Google Scholar]

- Worrell, F.; Cross, W., Jr.; Vandiver, B. Nigrescence theory: Current status and challenges for the future. J. Multicult. Couns. Dev. 2001, 29, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, W.E., Jr. Shades of Black: Diversity in African-American Identity; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, E.; Omari, S. Race, class, and the dilemmas of upward mobility for African Americans. J. Soc. Issues 2003, 59, 785–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam Webster Culture. 2019. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/culture (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- Hill Collins, P. Fighting Words: Black Women and the Search for Justice; University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Truth, S. Ain’t I a Woman? Speech Delivered at the Women Rights Convention, Akron, Ohio. 1851. Available online: http://sojournertruthmemorial.org/sojourner-truth/her-words/ (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- Hill Collins, P. Black Feminist Thought; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shields, S. Gender: An intersectionality perspective. Sex Roles 2008, 59, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Hucles, J.V.; Davis, D.D. Women and women of color in leadership: Complexity, identity, and intersectionality. Am. Psychol. 2010, 65, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, W., Jr. Comments Made during the Identity Development Reading Group Discussion; University of Nevada, Las Vegas: Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, W., Jr. The Thomas and Cross models of psychological nigrescence: A review. J. Black Psychol. 1978, 5, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R. The transracial adoption paradox: History, research, and counselling implications of cultural socialization. Couns. Psychol. 2003, 31, 711–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, E.; Samek, D.; Keyes, M.; McGue, M.; Iacono, W. Identity development in a transracial environment: Racial/ethnic minority adoptees in Minnesota. Adopt. Q. 2015, 18, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claiborne, R.; Siegel, H. Transracial Adoption Can Provide a Loving Family and an Identity Struggle. 2010. Available online: https://www.amren.com/news/2010/03/transracial_ado/ (accessed on 27 May2019).

- Butler-Sweet, C. ‘Acting White’ and ‘Acting Black’ Exploring transracial adoption, middle-class families, and racial socialization. In Race in Transnational and Transracial Adoption; Treitler, V.B., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2014; pp. 204–225. [Google Scholar]

- Parham, T. Psychological nigrescence revisited: A foreword. J. Multicult. Couns. Dev. 2001, 29, 162–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]