Religion and Negotiation of the Boundary between Majority and Minority in Québec: Discourses of Young Muslims in Montréal CÉGEPs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Context

2.1. Secularism and “Majority” Identity in Québec

Among some Quebecers, this counter-reaction targets immigrants, who have become, to some extent, scapegoats. What has just happened in Québec gives the impression of a face-off between two minority groups [Québec francophones in Canada and immigrant-background minorities in Québec], each of which is asking the other to accommodate it. The members of the ethnocultural majority are afraid of being swamped by fragile minorities that are worried about their future.[18] (p. 18)

2.2. Immigrant-Background Youth, Boundary Negotiation, and Islam

3. The Analytical Framework: Rapport with the Majority Group, the Boundary, and Identification

4. The Methodological Approach

5. Rupture with the Majority Group

5.1. Boundary Infancy, Elementary School

I really liked the teachers, I found that they seemed passionate about their work and everything, especially one that I had in Grade 3 and 4, since this one in particular made us do like a lot of enriching activities and he really helped to enrich our French, you could really see that it was close to his heart.

5.1.1. Awareness of Stigma

They didn’t really understand it, but they said, for example, what are you wearing? And so I told them I was wearing the hijab and that’s part of my identity. People thought it was strange because they were not really used to it. For sure, when you’re little, it’s like a little difficult because we don’t have, we lose self-confidence more easily.

Yes, really from students, I do not remember too much, but I remember from the teachers, my preschool teacher, there was an episode where once she hit me on the head with a big book, I do not know, for sure she was a bit racist, it showed, my brother and sister already knew, I think my mother already knew.

When I spoke in class and stuff, her reactions were a little disproportionate. She sent me to the principal’s office for having, I don’t know, for not having put away my book at the right time, when the reading period was over, or because she thought my answers were inappropriate.

It’s crazy for me that an event that happened in the United States could have affected my life like that, but on 11 September 2001, from that moment on... When the attacks there happened, the effect wasn’t felt right away, but in the years that followed, it was at that moment that the attitude of the people changed.

I did not have to be ashamed to be Muslim, I reacted in a way that was pretty [...]. I tended to make pretty inappropriate jokes about the subject, from the age of 8, I started making jokes about terrorists when someone reacted like that, to make comments like, “What? Are you afraid I’ll blow up your house?”

5.1.2. Silencing the Experience of Racism?

There were some with whom I got along really well, there were some with whom I did not get along so well, but I don’t think it was racism, I think more that it’s I was new, and I was a little different, a little quiet, but after I came out of my shell, it went well.

In kindergarten, they adored me, I was really adorable to them. But in elementary school, they didn’t like me much, I was a little bit the difficult child, I was in my corner, my own world, yes.

5.2. Boundary Solidification, High School

5.2.1. The Narrative of the Québec Identity at School

Me, I think it was mostly repetitive because, since elementary school, you learn about Amerindians, after that you learn a little of the history of Québec, we learned that in elementary school it’s the same thing in high school.(Amilda (Female, Ghana))

There are many of us whose peoples were colonized by the French, by the English, so our first reaction was not “poor little francophones,” but it was more “weren’t there already people here when the French arrived? So why should we be so sad that the French were conquered when they themselves had conquered the Amerindians?”.(Bouchra (Female, Algeria))

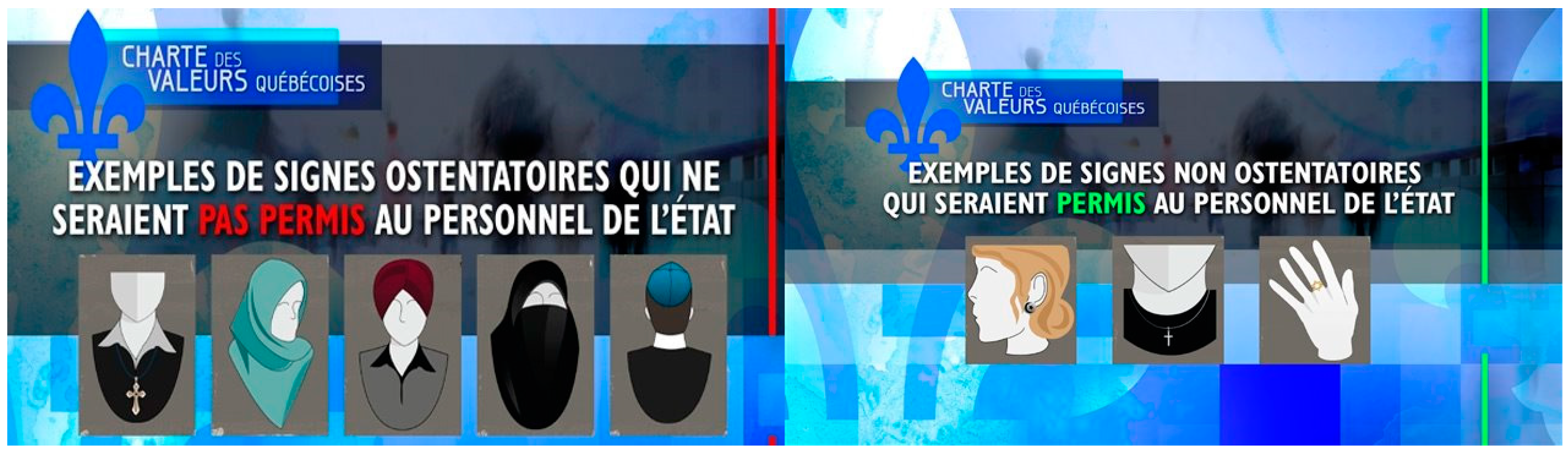

5.2.2. The Charter of Values, a Flashpoint

I like secular […] secularism, it’s not... I don’t know, but in my view, it’s not against all religion [...] so it would be stupid to say, right, you allow the cross, but you do not allow the hijab and you call yourself secular. Secularism is not an attachment to being against religion, it is detachment from religion.(Fahim (Male, Iran))

I think it’s aimed too much at Muslims, it’s really about Muslims, because a Christian is never going to wear a cross so huge it sticks out, and the majority is already secular anyways.(Neda (Female, Iran))

That’s the next step and that’s what’s happening with the Charter, we can see it. You can say it’s a question of religion, but there are many, many racial stereotypes that are starting to emerge. And we start to see the real face of people, the real opinion that they have of the people around them, and it’s scary.(Malika (Female, Morocco))

5.2.3. Representation by Deeds: Lived Racism

Especially since the Charter business. [...] Then yeah, the worst thing is that people look at you like you’re an idiot because you follow that. As if I were a submissive woman and all.

I remember, I was out and there was one woman who said: Hey! Do you have a bomb in your bag? [...] At one point, I went into a small shop and the woman shouted Lord! She looked at me and she shouted.(Rihab (Female, Algeria))

I was with my friend, she was parking her car [...] there was another car [...] and a man came with his wife and he told us: go back to your country, you do not belong here, f--- you.

They wanted us to speak French, to have their values, their ideals, to have the same vision of what it meant to be in a democracy, to be liberals, to be independent and autonomous [...], but when the time came to interact with us, most of the time we felt clearly that we were not Quebecers, that they themselves always saw us as immigrants and as people from our country of origin.

I look white, so people when they meet me assume that I was from one of these countries, either from France or something because I look like a Quebecer, I don’t look Algerian, and when I tell them, I immediately see a change in their personality, in how they treated me.

Now, here everyone... You go to the cafeteria, everyone is with everyone, here it’s much more mixed.(Amilda (Female, Ghana))

People mix more I would say because we don’t know each other. You have a class with 30 people [...] so you’re never with the same people.(Amilda (Female, Ghana))

5.2.4. A Negative Representation of “Québec Culture”

I believe that by forcing children, especially children of immigrants, to shun their own culture for the benefit of Québec culture, they disgust them. [...] We were above all tired of being taken for idiots, to be told that our culture was less important, that our culture was not part of the Québec community as such.(Bouchra (Female, Algeria))

They wonder afterward why people treat them as ignorant, they don’t budge, they do not want to see. And that’s something I noticed in Québec culture, these are not people who like to look beyond the tip of their nose. ‘This is what happens here, nothing else; what happens elsewhere we don’t care and it’s not important, it’s not here’.(Malika (Female, Morocco))

Then, with my parents, we joke, we ask ‘what’s their culture, poutine, beer, hockey,’ what is their culture, really?(Neda (Female, Iran))

I call it the white-washed world, becoming Québécois in your head.(Neda (Female, Iran))

5.3. Respecting “Québec Values”: From Criticism to Support

More freedom at home, that’s a big deal. At my house, you come home, you didn’t have a good grade on the exam, you do not go out for a week; while at their house, it’s neoliberal, I would say, in the sense that the parents let them do what they want.(Leyla (Female, Guyana))

Québec values, it’s above all open-mindedness, always freedom, but above all I find that, in Québec especially, it’s openness of mind they teach us.

My father, he’s very religious, very conservative on that. For him, people’s roles are very rigid, there is a way for women to act, to dress, to interact with others. [...] For me, it’s something that makes no sense, quite honestly; gender roles, it’s ridiculous.(Bouchra (Female, Algeria))

Since I grew up in a more Western culture, and I know more about my religion, I know the difference between culture and religion. Over there [in Algeria], they mix them up and then it annoys me because they act unjustly, things that are not right [...] and religion condemns that. But they, because it’s cultural, they say it’s okay.(Rihab (Female, Algeria))

5.4. A Typology of Boundary Negotiation

5.4.1. A Harmonious Rapport

When I say Quebecer, it’s not that I don’t call myself Canadian, but it’s more that I associate myself with Québec. I also like the Canadian identity.

The reality of being a second-generation immigrant is to have some cultural baggage that others do not have, it’s more things to share, it’s like having two cultural suitcases, we have the Québec baggage, we have the one from our own country.

So far, I consider myself African-Canadian, not a Quebecer; yes, I live in Québec, it’s been a long time, but the country is Canada.

5.4.2. A Tense Rapport

When it came time to interact with us, most of the time, we felt very clearly that we were not Quebecers, that even they saw us as immigrants.

When we say we are Montrealers, it can mean that we come from all over the world, but we identify with the values and dreams that are born in this city.

You know why I don’t wear a normal little headscarf like girls with jeans and everything? Because I told myself that I’d wear it like that. Whether I wear the niqab or a little scarf, there will always be... They will know that I am different. So while I’m at it, I’ll go with what I like [...] they will never accept us.

It’s since I put on the veil that I felt [...] it draws a line; it makes you not one of us. [...] I have been disgusted since the Charter affair.

I’m going to be honest, it’s the only thing that pulled me back from suicide [...] it’s the only thing that makes me want to live every morning [...], it’s the only thing that consoles me, that keeps me together.(Rihab (Female, Algeria))

5.4.3. An Indifferent Rapport

My sense of belonging is not with Québec, it is with Montréal, I love Montréal, I love the diversity of Montréal.

They [anglophones] were more interested in knowing our cultures [...] they wanted to learn. Which is what I think was lacking with francophones because they had preconceived ideas about our religions, our cultures, our values.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Guide

- Individual interview—English version.

- Interview questions—CEGEP students from immigrant backgrounds who have attended a French primary school and a French high school in Montréal.

- Family experience during childhood and adolescence.

- Primary and High school experiences in Montréal (in French schools).

- CEGEP experience in Montréal.

- Linguistic, cultural and territorial identification.

- Future plans.

- 1.

- To start with, I would like you to tell me about your family:

- Family members;

- Language(s) spoken at home;

- Schooling and work of your parents in their country of origin;

- Work of your parents in the province of Québec;

- Migration pathway (parent’s country of origin, reasons for migrating, acculturation, and integration process, etc.);

- Travels in your parents’ country of origin?

- Why those travels? Attachment to the country of origin?

- Family social networks in Montréal;

- Parents’ and sibling’s ways of relating to languages (namely French and English); and

- Parents’ and sibling’s ways of relating to Bill 101, education and French public school

- 2.

- What are your memories of your experience at a French primary school?

- School(s) attended and parents’ rationale for explaining their school choice;

- Ways of relating to school, teaching, pedagogy, curriculum (course contents);

- Academic record (success, difficulties, etc.);

- Teachers’ attitude toward diversity (especially linguistic diversity);

- Have you witnessed or been victim of linguistic, cultural or religious conflicts? Unfavorable treatments directly related to linguistic, cultural, and religious diversity?

- Ways of relating to different school employees (teachers, principals, etc.);

- Ways of relating to peers (languages spoken with peers, interactions, intergroup categorizations, experiences of discrimination, etc.);

- Ways of relating to the French language and to Bill 101; and

- Senses of belonging (to language, culture, territory, etc.).

- 3.

- What are your memories of your experience at a French High School?

- Schools(s) attended and rationale behind the choice of the school;

- Ways of relating to school, teaching, pedagogy, curriculum (history, language courses, ECR—éthique et culture religieuse—courses, etc.);

- ○

- First question: Are there any course that had an influence on you during high school? Why?

- ○

- What do you think of the history courses that you had in high school?

- ○

- What place do you feel you have in this history and toward the groups portrayed (mention the three groups if respondents do not know what to answer: Francophones, Anglophones, Aboriginals).

- Academic record (success, difficulties, etc.);

- Teachers’ attitude toward diversity;

- Ways of relating to different school employees (teachers, principals, guidance counsellors, etc.);

- Ways of relating to peers (languages spoken with peers, interactions, intergroup categorizations, experience of discrimination, conversations about CEGEP vocational choices, etc.);

- Ways of relating to the French language and to Bill 101; and

- Sense of belonging (to language, culture, territory, etc.).

- 4.

- Tell me about your school pathway at the CEGEP level:

- First registration (date, year); and

- Different programs attended?

- 5.

- What led you to choose your current program?

- For the curriculum content?

- For career opportunities?

- Importance of social network?

- Influence from parents, guidance counsellors, friends, teachers, school principals, etc.? and

- Linguistic reasons explaining your choice?

- 6.

- Could you describe me how you came to choose your CEGEP?

- Influence from parents, guidance counsellors, friends, teachers, school principals, etc.?

- 7.

- What are your memories of your CEGEP experience?

- Day-to-day experience;

- Ways of relating to CEGEP, teaching, pedagogy, curriculum (courses content);

- Ways of relating to different CEGEP employees (teachers, principals, guidance counsellors, etc.);

- Teachers’ attitude toward linguistic, cultural, and religious diversity;

- Ways of relating with peers (languages spoken with peers, interactions, intergroup categorizations, etc.);

- School integration, social integration, linguistic integration (French, English, or Allophone friends, Friends’ ethnic origins, process of integration over time);

- Ways of relating to the CEGEP official language: In the courses, with friends, with the administration, etc. (Does your way of relating to the CEGEP official language has changed over time?);

- Sense of belonging (to language, culture, territory, etc.); and

- Ways of relating to languages.

- 8.

- If I simply ask you ‘Who you are?’, what would you answer spontaneously?

- Importance or not of language(s)?

- Importance or not of culture(s)?

- Attachment to Canada, to the province (or territory), to a town, to a specific place, etc.? and

- Importance of several characteristics such as age, sex, social class, etc.?

- 9.

- What do you plan to do once you have graduated from CEGEP?

- To start university? Which program? In which language? In which city, province, country?

- To start working? In which languages? In which city, province, city? and

- Geographic mobility

Appendix B. Categories of Content Analysis

- (A)

- Schooling experiences:

- -

- Schooling choices and trajectories;

- -

- Welcoming and inclusion;

- -

- Value strife in schooling context;

- -

- Cultural, linguistic, and religious diversity at school; and

- -

- Relationships with teachers and principals

- (B)

- Religious practices at school:

- -

- Curiosity and exploration of religions and religious practices;

- -

- Religious practices in Québec;

- -

- Experiences of religions in school; and

- -

- The teaching of religions in school (ECR).

- (C)

- Experiences of racism:

- -

- Experiences of discrimination;

- -

- Experiences of exclusion;

- -

- Feeling of unfairness;

- -

- Prejudices, stereotypes; and

- -

- Experiences of colonialism, assimilation.

- (D)

- Rapport to country of origin:

- -

- Experiences of migration;

- -

- Family network with country of origin;

- -

- Representations of country of origin; and

- -

- Experiences in the country of origin.

- (E)

- Rapport to Québec and its population:

- -

- Québec values representations;

- -

- Immigrant values representations; and

- -

- Experiences and relationships with Québec populations.

- (F)

- Identification:

- -

- Identity categories adopted and positioning; and

- -

- Identity categories assigned or contested.

- (G)

- Social networks and friends:

- -

- Groups fluidity or separation;

- -

- Choice of friends and social networks;

- -

- Peer pressure;

- -

- Isolation, exclusion, invisibility;and

- -

- Relationships with the opposite sex.

- -

- Creation of the boundary;

- -

- Straddle the boundary;

- -

- Cross the boundary;

- -

- Maintain or escalate the boundary;

- -

- Question, refuse or contest the boundary;

- -

- Be assigned the boundary;

- -

- In between boundaries; and

- -

- Being free of boundaries.

- (A)

- In relation to family life:

- -

- Teenage years and forbidden activities (going out, drinking, smoking, dating); and

- -

- Experiences of Ramadan (emergence of a religious conscience).

- (B)

- In relation to the majority group:

- -

- 9-11 attacks in the USA;

- -

- Charter of Values for secularism;

- -

- Schooling experiences at elementary level (racism, discrimination);

- -

- ECR course during secondary level studies—(prejudice, racism, feeling of unfairness);

- -

- Imposition of French as the schooling language (feeling of unfairness, discrimination);

- -

- Schooling experiences at secondary level (ethnic and migrant identities resurgence, groups separation, distance from the Quebecer identification); and

- -

- The adoption of the veil.

References

- Chastenay, M.H.; Pagé, M. Le rapport à la citoyenneté et à la diversité chez les jeunes collégiens québécois: Comment se distinguent les deuxièmes générations d’origine immigrée? In Les Deuxième Génération en France et au Québec; Venel, N., Eid, P., Potvin, M., Eds.; Athéna: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2007; pp. 239–256. [Google Scholar]

- Statistique Canada. Immigration et Diversité Ethnoculturelle au Canada; Enquête Nationale Auprès des Ménages, 2011; Produit No. 99-010-X2011001 au Catalogue de Statistique Canada; Statistique Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2013; p. 24.

- Benhadjoudja, L. Les controverses autour du hijab des femmes musulmanes: Un débat laïque? In Penser la Laïcité Québécoise. Fondements et Défense d’une Laïcité Ouverte au Québec; Lévesque, S., Ed.; Presses de l’Université Laval: Québec, QC, Canada, 2014; pp. 109–127. [Google Scholar]

- Baubérot, J. La Laïcité Falsifiée; La Découverte: Paris, France, 2014; p. 224. [Google Scholar]

- Bilge, S. Reading the Racial Subtext of the Québécois Accommodation Controversy: An Analytics of Racialized Governmentality. Polit. S. Afr. J. Polit. Stud. 2013, 40, 157–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejean, F.; Mainich, S.; Manaï, B.; Touré Kapo, L. Les Étudiants Face à la Radicalisation Religieuse Conduisant à la Violence. Mieux les Connaître pour Mieux Prévenir; Research Report; IRIPI: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2016; p. 83. Available online: http://iripi.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/iripi-rapport-radicalisation.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2018).

- Hafez, M.; Mullins, C. The Radicalization Puzzle: A Theoretical Synthesis of Empirical Approaches to Homegrown Extremism. Stud. Conf. Terror. 2015, 38, 958–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crettiez, X. Penser la radicalisation. Une sociologie processuelle des variables de l’engagement violent. Revue Française de Science Politique 2016, 66, 709–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, R. Linguistic and Religious Pluralism: Between Difference and Inequality. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2015, 41, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juteau, D. L’ethnicité et Ses Frontières, 2nd ed.; Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2015; p. 306. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère de l’Éducation du Québec. Les États généraux sur l’Éducation 1995–1996, Rénover Notre Système D’éducation: Dix Chantiers Prioritaires; Commission des États Généraux, Rapport Final; Gouvernement du Québec: Québec, QC, Canada, 1996.

- Groupe de Travail sur la Place de la Religion à L’école. Laïcité et Religions. In Perspective Nouvelle Pour L’école Québécoise [Version Abrégée]; Gouvernement du Québec: Québec, QC, Canada, 1999; p. 110. Available online: http://collections.banq.qc.ca/ark:/52327/bs40898 (accessed on 29 August 2018).

- Ministère de L’éducation, du Loisir et du Sport. La mise en Place d’un Programme ECR. Une Orientation D’avenir Pour Tous les Jeunes du Québec; Gouvernement du Québec: Québec, QC, Canada, 2005.

- Tremblay, S. École et Religions. Genèse du Nouveau Paris Québécois; Fides: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2010; p. 264. [Google Scholar]

- Cours Suprême du Canada. Jugement Multani c. Commission Scolaire Marguerite-Bourgeoys; Dossier 30322; Cours Suprême du Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2006; pp. 256–325. [Google Scholar]

- Woehrling, J. Les fondements et les limites de l’accommodement raisonnable en milieu scolaire. In L’accommodement Raisonnable et la Diversité Religieuse à L’école Publique; Mc Andrew, M., Milot, M., Imbeault, J.-S., Eid, P., Eds.; Fides: Montréal, QC, Canada; pp. 43–56.

- Potvin, M. Crise des Accommodements Raisonnables. Une Fiction Médiatique; Athéna: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2008; p. 280. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard, G.; Taylor, C. Building the Future. A Time for Reconciliation; Report, Commission de Consultation sur les Pratiques D’accommodement Reliées aux Différences Culturelles; Gouvernement du Québec: Québec, QC, Canada, 2008; p. 307. Available online: https://www.mce.gouv.qc.ca/publications/CCPARDC/rapport-final-integral-en.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2018).

- Jobin, M. La Charte des Valeurs Proposée Par Le Gouvernement Québécois Est-Elle un Outil de Communautarisme? Radio-Canada International, 2013. Available online: http://www.rcinet.ca/fr/2013/09/10/la-charte-des-valeurs-proposee-par-le-gouvernement-quebecois-est-elle-un-outil-de-communautarisme/ (accessed on 27 April 2018).

- Ferrari, A. De la politique à la Technique: Laïcité Narrative et Laïcité du Droit. Pour une Comparaison France/Italie. In Le Droit Ecclésiastique en Europe et à ses Marges (XVIIIe-XXe Siècles); Basdevant-Gaudernet, B., Jankowiak, F., Delannoy, J.-P., Eds.; Peeters: Leuven, Belgium, 2009; pp. 333–345. [Google Scholar]

- Dalpé, S.; Koussens, D. Les discours sur la laïcité pendant le débat sur la «Charte des valeurs de la laïcité». Une analyse lexicométrique de la presse francophone québécoise. Rech. Sociograph. 2016, 57, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélair-Cirino, M. Loi sur la Neutralité Relig Uvert ou pas? Le Devoir, 2017. Available online: https://www.ledevoir.com/politique/Québec/511149/loi-aur-la-neutralite-religieuse (accessed on 29 August 2018).

- Lamy, G. Cartographie de la Controverse Entourant le Rapport de la Commission Bouchard-Taylor. Master’s Thesis, Université du Québec à Montréal, Montréal, QC, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Maclure, J.; Taylor, C. Laïcité et Liberté de Conscience; Boréal: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2010; p. 168. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard, G. L’interculturalisme. Un Point de vue Québécois; Boréal: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2012; p. 286. [Google Scholar]

- Eid, P. Les nouveaux habits du racisme au Québec: L’altérisation des arabo-musulmans et la (re)négociation du Nous national. In Au Nom de la Sécurité; Lamoureux, D., Dupuis-Déri, F., Eds.; Prologie: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2016; pp. 86–87. [Google Scholar]

- Milot, M. École et religion au Québec. Spirale 2007, 39, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeau, F.; Helly, D. Une extrême droite en émergence? Les pages Facebook pour la charte des valeurs québécoises. Rech. Sociograph. 2016, 57, 505–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potvin, M.; Nadeau, F. L’extrême-droite au Québec: Une menace réelle? Relations 2017, 791, 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chikkatur, A. Difference Matters: Embodiment of and Discourse on Difference at an Urban Public High School. Anthropol. Educ. Q. 2012, 43, 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Villers, J. Entre injonctions contradictoires et bricolages identitaires: Quelles identifications pour les descendants d’immigrés marocains en Belgique? Lien Social et Politiques 2005, 53, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatier, C. Figures identitaires d’élèves issus de la migration maghrébine à l’école élémentaire en France. Éducation et Francophonie 2006, 34, 111–132. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven, M. Stratégies identitaires de jeunes issus de l’immigration et contextes scolaires: Vers un renouvellement des figures de la reproduction culturelle. Éducation et Francophonie 2006, 34, 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Quintana, S.M.; Segura Herrera, T.A.; Nelson, M.L. Mexican American High School Students’ Ethnic Self-Concepts and Identity. J. Soc. Issues 2010, 66, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meintel, D.; Kahn, E. De génération en génération: Identités et projets identitaires de Montréalais de la «deuxième génération». Ethnologies 2005, 27, 131–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafortune, G.; Kanouté, F. Vécu identitaire d’élèves de première et de deuxième génération d’origine haïtienne. Revue de l’Université de Moncton 2007, 38, 33–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbach, M. “Eux autres versus nous autres”: Adolescent Students’views on the Integration of Newcomers. Int. Educ. 2010, 21, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mc Andrew, M. Le remplacement du marqueur linguistique par le marqueur religieux en milieu scolaire. In Les Relations Ethniques en Question. Ce qui a Changé Depuis le 11 Septembre 2001; Renaud, J., Pietrantonio, L., Bourgeault, G., Eds.; Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2002; pp. 31–148. [Google Scholar]

- Magnan, M.-O.; Larochelle-Audet, J. Immigrant-Background Youth in Québec: Portrait, Issues, and Debates. In Immigrant Youth in Canada. Theoretical Approaches, Practical Issues, and Professional Perspectives; Wilson-Forsberg, S., Robinson, A.M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Don Mills, ON, Canada, 2018; pp. 251–269. [Google Scholar]

- Magnan, M.-O.; Darchinian, F.; Larouche, É. École québécoise, frontières ethnoculturelles et identités en milieu pluriethnique. Minorités Linguistiques et Société 2016, 7, 97–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, G.; Mekki-Berrada, A.; Rousseau, C.; Lyonnais-Lafond, G.; Jamil, U.; Cleveland, J. Impact of the Charter of Québec Values on psychological well-being of francophone university students. Transcult. Psychiatry 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Hage, H. Pilot Study on the Charter of Values Impact on a Multiethnic Group of College Students Enrolled in a Montréal College; Unpublished Report; Collège Rosemont: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, C.; Hassan, G.; Lecompte, V.; Oulhote, Y.; El Hage, H.; Mekki-Berrada, A.; Rousseau-Rizzi, A. Le défi du vivre Ensemble: Les Déterminants Individuels et Sociaux du Soutien à la Radicalisation Violente des Collégiens et Collégiennes au Québec; Research Report; SHERPA: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2016; p. 61. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, F. Les groupes ethniques et leurs frontières. In Théories de L’ethnicité; Poutignat, P., Streiff-Fenart, J., Eds.; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 2008; pp. 203–249. [Google Scholar]

- Poutignat, P.; Streiff-Fenart, J. (Eds.) Théories de L’ethnicité; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 2008; p. 304. [Google Scholar]

- Hervieu-Léger, D. La lignée croyante en question. Espaces Temps 2000, 74–75, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, R.; Junqua, F. Au-Delà de l’«identité». Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales 2001, 139, 66–85. [Google Scholar]

- Magnan, M.O.; Darchinian, F.; Larouche, É. Identifications et rapports entre majoritaires et minoritaires. Discours de jeunes issus de l’immigration. Diversité Urbaine 2017, 17, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertaux, D. Le Récit de vie, 3rd ed.; Armand Colin: Paris, France, 2010; p. 126. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.W. Globalisation and acculturation. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2008, 32, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchamma, Y. Francisation, Scolarisation et Socialisation des Élèves Immigrants en Milieu Minoritaire Francophone du Nouveau-Brunswick: Quels Défis et Quelles Perspectives; Centre Métropolis Atlantique: Halifax, NS, Canada, 2009; Volume 21, pp. 1–50.

- Bouchamma, Y. L’intervention Interculturelle en Milieu Scolaire; Les Éditions de la Francophonie: Caraquet, NB, Canada, 2009; p. 194. [Google Scholar]

- Kanouté, F.; Vatz Laaroussi, M.; Rachédi, L.; Tchimou Doffouchi, M. Familles et réussite scolaire d’élèves immigrants du secondaire. Revue des Sciences de L’éducation 2008, 34, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Emerique, M. Choc culturel et relations interculturelles dans la pratique des travailleurs sociaux. Formation par la méthode des incidents critiques. Cahiers de Sociologie Économique et Culturelle 1984, 2, 183–218. [Google Scholar]

- Nizet, J.; Rigaux, N. La Sociologie de Erving Goffman, 1st ed.; La Découverte: Paris, France, 2005; p. 128. [Google Scholar]

- Winance, M. Handicap et normalisation. Analyse des transformations du rapport à la norme dans les institutions et les interactions. Politix 2004, 17, 201–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, S.; Triki-Yamani, A. Jeunes adultes immigrants de deuxième génération. Dynamiques ethnoreligieuses et identitaires. Can. Ethn. Stud. 2011, 43–44, 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giry, J. Le conspirationnisme. Archéologie et morphologie d’un mythe politique. Diogène 2015, 249–250, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, R. Rethinking Ethnicity: Arguments and Exploration, 2nd ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008; p. 224. [Google Scholar]

| Rapport with Majority Group | Boundary Negotiation |

|---|---|

| Harmonious rapport | Cross the boundary Straddle the boundary |

| Tense rapport | Be assigned the boundary Escalate the boundary |

| Indifferent rapport | Break the boundary |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tremblay, S.; Magnan, M.-O.; Levasseur, C. Religion and Negotiation of the Boundary between Majority and Minority in Québec: Discourses of Young Muslims in Montréal CÉGEPs. Educ. Sci. 2018, 8, 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8040183

Tremblay S, Magnan M-O, Levasseur C. Religion and Negotiation of the Boundary between Majority and Minority in Québec: Discourses of Young Muslims in Montréal CÉGEPs. Education Sciences. 2018; 8(4):183. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8040183

Chicago/Turabian StyleTremblay, Stéphanie, Marie-Odile Magnan, and Catherine Levasseur. 2018. "Religion and Negotiation of the Boundary between Majority and Minority in Québec: Discourses of Young Muslims in Montréal CÉGEPs" Education Sciences 8, no. 4: 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8040183

APA StyleTremblay, S., Magnan, M.-O., & Levasseur, C. (2018). Religion and Negotiation of the Boundary between Majority and Minority in Québec: Discourses of Young Muslims in Montréal CÉGEPs. Education Sciences, 8(4), 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8040183