Teacher Education Students’ Practices, Benefits, and Challenges in the Use of Generative AI Tools in Higher Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Students’ Practices and Their Engagement with GenAI

2.2. Educational Benefits of AI Use in Higher Education

2.3. Challenges and Limitations in AI Adoption

3. Research Aim

- (i)

- What practices do teacher education students adopt when employing GenAI tools for academic purposes?

- (ii)

- What benefits do teacher education students perceive from integrating GenAI tools for academic purposes?

- (iii)

- What challenges do teacher education students encounter in integrating GenAI tools for academic purposes?

4. Research Method

5. Research Instrument and Strategy of Data Analysis

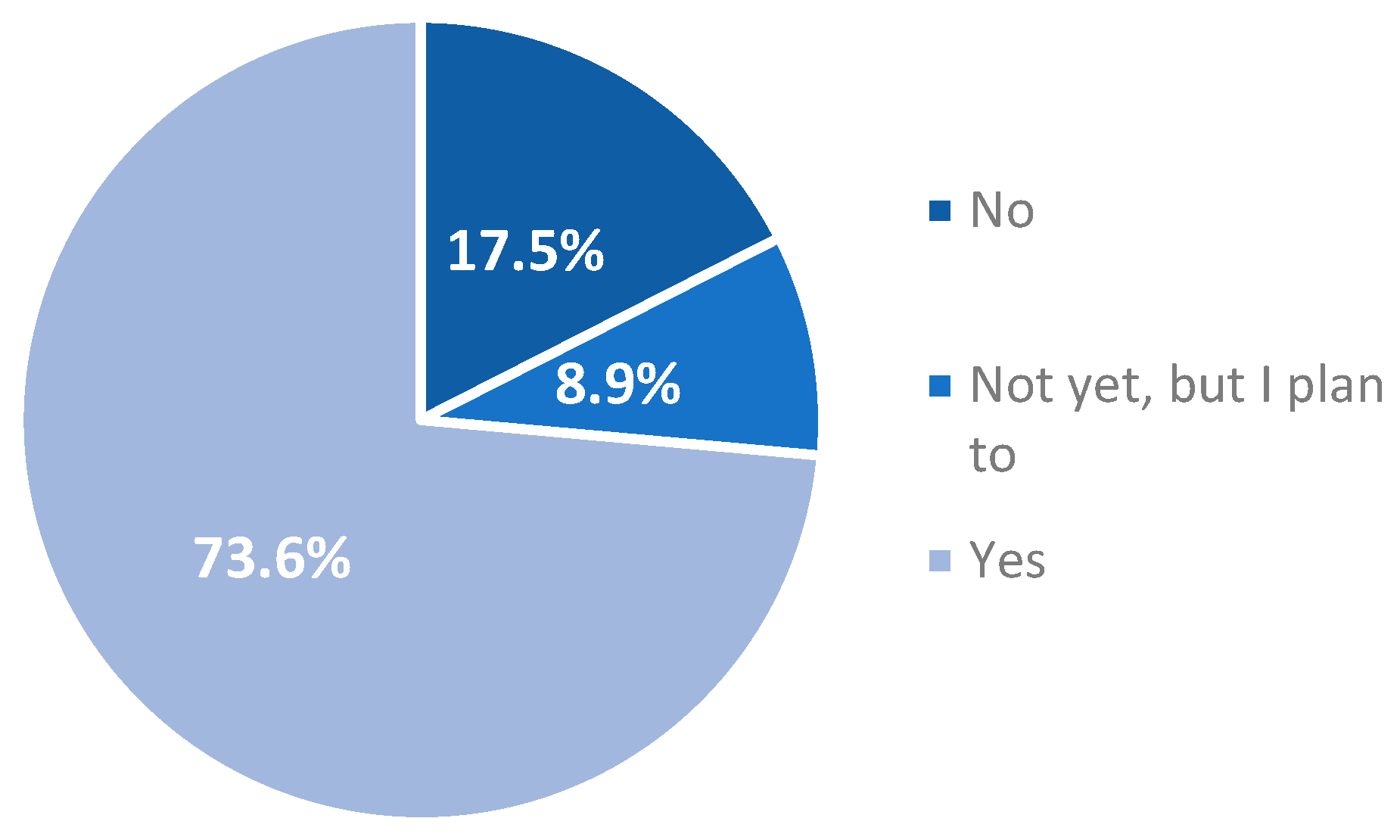

6. Results

7. Discussion

7.1. Implications for Pre-Service Teacher Preparation

7.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ali, M. S., Suchiang, T., Saikia, T. P., & Gulzar, D. D. (2024). Perceived benefits and concerns of ai integration in higher education: Insights from India. Educational Administration: Theory and Practice, 30(5), 656–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y., Yu, J. H., & James, S. (2025). Investigating the higher education institutions’ guidelines and policies regarding the use of generative AI in teaching, learning, research, and administration. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 22, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A. N., Ahmad, S., & Bhutta, S. M. (2024). Mapping the global evidence around the use of ChatGPT in higher education: A systematic scoping review. Education and Information Technologies, 29(9), 11281–11321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhullar, P. S., Joshi, M., & Chugh, R. (2024). ChatGPT in higher education—A synthesis of the literature and a future research agenda. Education and Information Technologies, 29(16), 21501–21522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, C. K. Y., & Hu, W. (2023). Students’ voices on generative AI: Perceptions, benefits, and challenges in higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S., & Bhattacharjee, K. K. (2020). Adoption of artificial intelligence in higher education: A quantitative analysis using structural equation modelling. Education and Information Technologies, 25(5), 3443–3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T. K. F. (2024). Future research recommendations for transforming higher education with generative AI. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 6, 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, D. R. E., Cotton, P. A., & Shipway, J. R. (2024). Chatting and cheating: Ensuring academic integrity in the era of ChatGPT. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 61(2), 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabis, A., & Csáki, C. (2024). AI and ethics: Investigating the first policy responses of higher education institutions to the challenge of generative AI. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2021). Ethics by design and ethics of use approaches for artificial intelligence (1.0), European commission—DG research and innovation. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/funding-tenders/opportunities/docs/2021-2027/horizon/guidance/ethics-by-design-and-ethics-of-use-approaches-for-artificial-intelligence_he_en.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- European Parliament & Council. (2024). Regulation (EU) 2024/1689—Artificial intelligence act. Official Journal of the European Union, 3(1). Available online: https://artificialintelligenceact.eu/article/3/ (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Gao, Z., Cheah, J.-H., Lim, X.-J., & Luo, X. (2024). Enhancing academic performance of business students using generative AI: An interactive-constructive-active-passive (ICAP) self-determination perspective. International Journal of Management Education, 22(2), 100958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökçearslan, S., Tosun, C., & Erdemir, Z. G. (2024). Benefits, challenges, and methods of artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots in education: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Technology in Education, 7(1), 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humble, N. (2025). Higher education AI policies—A document analysis of university guidelines. European Journal of Education, 60(3), e70214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutson, J., Jeevanjee, T., Graaf, V., Lively, J., Weber, J., Weir, G., Arnone, K., Carnes, G., Vosevich, K., Plate, D., Leary, M., & Edele, S. (2022). Artificial intelligence and the disruption of higher education: Strategies for integration across disciplines. Creative Education, 13(12), 3953–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, G. J., Xie, H., Wah, B. W., & Gašević, D. (2020). Vision, challenges, roles, and research issues of artificial intelligence in education. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M., Murray, L., Aldulayani, F., Ali, S., Youcefi, N., & Haroon, S. (2025). From Europe to Ireland: Artificial intelligence pivotal role in transforming higher education policies and guidelines. University of Limerick. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y., Yan, L., Echeverria, V., Gašević, D., & Martinez-Maldonado, R. (2025). Generative AI in higher education: A global perspective of institutional adoption policies and guidelines. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 8, 100348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H. (2024). From concerns to benefits: A comprehensive study of ChatGPT usage in education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 21(1), 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasneci, E., Seßler, K., Küchemann, S., Bannert, M., Dementieva, D., Fischer, F., Gasser, U., Groh, G., Günnemann, S., Hüllermeier, E., Krusche, S., Kutyniok, G., Michaeli, T., Nerdel, C., Pfeffer, J., Poquet, O., Sailer, M., Schmidt, A., Seidel, T., … Kasneci, G. (2023). ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learning and Individual Differences, 103, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Yu, S., Detrick, R., & Li, N. (2025). Exploring students’ perspectives on Generative AI-assisted academic writing. Education and Information Technologies, 30(1), 1265–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Y., Lee, W. K., Jee, S. J., & Sohn, S. Y. (2025). Discovering AI adoption patterns from big academic graph data. Scientometrics, 130(2), 809–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoth, N., Tolzin, A., Janson, A., & Leimeister, J. M. (2024). AI literacy and its implications for prompt engineering strategies. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 6, 100225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohnke, L., Zou, D., Ou, A. W., & Gu, M. M. (2025). Preparing future educators for AI-enhanced classrooms: Insights into AI literacy and integration. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 8, 100398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, G., Amzalag, M., Shaked, N., Zaguri, Y., Kohen-Vacs, D., Gal, E., Zailer, G., & Barak-Medina, E. (2024). Strategies for integrating generative AI into higher education: Navigating challenges and leveraging opportunities. Education Sciences, 14(5), 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavidas, K., Koskina, E., Pitsili, A., Komis, V., & Arvanitis, E. (2025). Humanities and social sciences students’ views on the use of AI tools for academic purposes: Practices, benefits, challenges, and suggestions. Advances in Mobile Learning Educational Research, 6(1), 1699–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Park, J., & McMinn, S. (2024). Using generative artificial intelligence/ChatGPT for academic communication: Students’ perspectives. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 34, 1437–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel-Villarreal, R., Vilalta-Perdomo, E., Salinas-Navarro, D. E., Thierry-Aguilera, R., & Gerardou, F. S. (2023). Challenges and opportunities of generative AI for higher education as explained by ChatGPT. Education Sciences, 13(9), 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, A., Wilson, A., Pereira Nunes, B., Del Medico, C., Slade, C., Bennett, D., Tyler, D., Seymour, E., Hepplewhite, G., Randell-Moon, H., Janine, A., McPherson, J., Game, J., Rhall, J., Myers, K., Absolum, K., Edmond, K., Nicholls, K., Adam, L., … Duke, Z. (2023). AAIN generative artificial intelligence (AI) guidelines (Version 1). Deakin University. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10779/DRO/DU:22259767.v1 (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Nechyporenko, V., Hordiienko, N., Pozdniakova, O., Pozdniakova-Kyrbiatieva, E., & Siliavina, Y. (2025). How often do university students use artificial intelligence in their studies? WSEAS Transactions on Information Science and Applications, 22, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulou, K. (2024). Generative artificial intelligence in higher education: Exploring ways of harnessing pedagogical practices with the assistance of ChatGPT. International Journal of Changes in Education, 1(2), 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niloy, A. C., Bari, M. A., Sultana, J., Chowdhury, R., Raisa, F. M., Islam, A., Mahmud, S., Jahan, I., Sarkar, M., Akter, S., Nishat, N., Afroz, M., Sen, A., Islam, T., Tareq, M. H., & Hossen, M. A. (2024). Why do students use ChatGPT? Answering through a triangulation approach. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 6, 100208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajany, P. (2021). AI Transformative influenceextending the tram to management student’s AI’s machine learning adoption [Doctoral dissertation, Franklin University]. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Y., Tan, M. X. Y., & Wang, J. (2024). Disciplinary differences in undergraduate students’ engagement with generative artificial intelligence. Smart Learning Environments, 11(1), 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasul, T., Nair, S., Kalendra, D., Robin, M., Santini, F. d. O., Ladeira, W. J., Sun, M., Day, I., Rather, R. A., & Heathcote, L. (2023). The role of ChatGPT in higher education: Benefits, challenges, and future research directions. Journal of Applied Learning and Teaching, 6(1), 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roll, I., & Wylie, R. (2016). Evolution and revolution in artificial intelligence in education. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 26, 582–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Rojas, L. I., Salvador-Ullauri, L., & Acosta-Vargas, P. (2024). Collaborative working and critical thinking: Adoption of generative artificial intelligence tools in higher education. Sustainability, 16(13), 5367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusdin, D., Mukminatien, N., Suryati, N., & Laksmi, E. D. (2024). Critical thinking in the AI era: An exploration of EFL students’ perceptions, benefits, and limitations. Cogent Education, 11(1), 2290342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Pilco, S. Z., & Yang, Y. (2022). Artificial intelligence applications in Latin American higher education: A systematic review. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 19(1), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C. A. G. D., Ramos, F. N., de Moraes, R. V., & Santos, E. L. D. (2024). ChatGPT: Challenges and benefits in software programming for higher education. Sustainability, 16(3), 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. V., & Hiran, K. K. (2022). The impact of AI on teaching and learning in higher education technology. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 12(13). Available online: https://articlearchives.co/index.php/JHETP/article/view/3553 (accessed on 8 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A. E., & Cardoso, P. (2025). Use of generative AI by higher education students. Electronics, 14(7), 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M. J., Dal Mas, F., Pesqueira, A., Lemos, C., Verde, J. M., & Cobianchi, L. (2021). The potential of AI in health higher education to increase the students’ learning outcomes. TEM Journal, 10(2), 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracke, C. M., Griffiths, D., Pappa, D., Bećirović, S., Polz, E., Perla, L., Di Grassi, A., Massaro, S., Skenduli, M. P., Burgos, D., Punzo, V., Amram, D., Ziouvelou, X., Katsamori, D., Gabriel, S., Nahar, N., Schleiss, J., & Hollins, P. (2025). Analysis of Artificial Intelligence Policies for Higher Education in Europe. International Journal of Interactive Multimedia and Artificial Intelligence, 9(2), 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sublime, J., & Renna, I. (2024). Is ChatGPT massively used by students nowadays? A survey on the use of large language models such as ChatGPT in educational settings. arXiv, arXiv:2412.17486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2021). Recommendation on the ethics of artificial intelligence. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/artificial-intelligence/recommendation-ethics (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Walter, Y. (2024). Embracing the future of artificial intelligence in the classroom: The relevance of AI literacy, prompt engineering, and critical thinking in modern education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 21(1), 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T. D. (2025). The development of policies on generative artificial intelligence in UK universities. IFLA Journal, 51(3), 722–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H. (2024, October 24–25). Towards responsible use: Student perspectives on ChatGPT in higher education. 23rd European Conference on E-Learning, Porto, Portugal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequency | Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Years of Study | 1 | 75 | 23.9 |

| 2 | 184 | 58.6 | |

| 3 | 34 | 10.8 | |

| 4 | 13 | 4.1 | |

| 5 | 3 | 1.0 | |

| >5 | 5 | 1.6 | |

| Gender | Male | 29 | 9.3 |

| Female | 282 | 89.8 | |

| Other | 3 | 0.9 | |

| Age | <=18 | 56 | 17.8 |

| 19 | 90 | 28.7 | |

| 20 | 111 | 35.4 | |

| 21 | 28 | 8.9 | |

| 22 | 11 | 3.5 | |

| >22 | 18 | 5.7 | |

| Departments of Education and Pedagogical Studies | Preschool Education | 190 | 60.5 |

| Philosophy | 82 | 26.1 | |

| Philology | 42 | 13.4 |

| Task | Never | Very Rarely | Rarely | Often | Very Often |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Text translation | 38.1% | 16.9% | 26.0% | 18.2% | 0.9% |

| Text paraphrasing | 26.4% | 18.6% | 22.1% | 29.4% | 3.5% |

| Literature processing (e.g., summarizing scientific articles) | 24.7% | 16.5% | 26.0% | 26.4% | 6.5% |

| Data analysis | 13.9% | 15.2% | 20.3% | 45.0% | 5.6% |

| Information searching | 2.2% | 4.3% | 13.4% | 46.8% | 33.3% |

| Study advice | 15.6% | 5.6% | 19.5% | 39.4% | 19.9% |

| Exam preparation | 20.8% | 13.0% | 20.8% | 31.2% | 14.3% |

| Help with references | 27.3% | 19.0% | 23.4% | 22.1% | 8.2% |

| Writing assignments | 20.8% | 19.5% | 25.5% | 22.9% | 11.3% |

| No. | Benefit Category | Frequencies | Percentages |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Information/Answer Finding (easiness, immediacy, big volume, info variety, new knowledge, sources) | 160 | 50.96% |

| 2 | Time Saving/Speed (save time, fast completion, quick answers) | 90 | 28.66% |

| 3 | Understanding and Simplification of Complex Concepts (content understanding, simplification of difficult concepts, explanation with accuracy, translanguaging) | 65 | 20.70% |

| 4 | Help with Assignments and Research (task completion, writing of essays, research references, brainstorming) | 60 | 19.11% |

| 5 | Study/Note Organization (focus aid, planning of tasks, note keeping, organizing content and curriculum) | 40 | 12.74% |

| 6 | Summarizing/Analyzing/Translating Texts (abstract, summary, translation, content analysis) | 35 | 11.15% |

| 7 | Idea Generation and Inspiration (inspiration, guidelines, content generation) | 30 | 9.55% |

| 8 | Critical Thinking and Skills (vocabulary enrichment, cognitive development, thinking ability) | 25 | 7.96% |

| 9 | Problem Solving/Clarification of Doubts (answer difficult questions/exercises/quizzes) | 20 | 6.37% |

| 10 | Performance/Effectiveness Improvement (promote learning, task completion, better performance) | 15 | 4.78% |

| 11 | Familiarization with Technology and New Tools (development of technological skills, digital literacy) | 10 | 3.18% |

| No. | Challenge Category | Frequencies | Percentages |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Over-reliance/Reduced Personal Effort (convenience, laziness, easy solutions, lack of effort, stop thinking, dependence, loss of critical thinking, ensconcing) | 180 | 57.32% |

| 2 | Plagiarism/Copying/Academic Integrity Issues (cheating, human replacement, lack of understanding, same answers) | 150 | 47.77% |

| 3 | Erosion of Critical Thinking/Deep Learning (passive learning, uncritical knowledge, reduced skills, cognitive hibernation) | 140 | 44.59% |

| 4 | Diminished Research Skills (less research/cross-checking) (not crosschecking sources, reduced research, no filtering of information, lack of reliability/diversity, monotony) | 110 | 35.03% |

| 5 | Inaccuracy, Misinformation, Reliability Concerns (wrong results, invalid sources, unreliability, untrustworthiness, missing information) | 105 | 33.44% |

| 6 | Reduced Creativity and Writing Skills (loss of imagination and creativity, loss of human workforce and worth, inability to produce written word) | 95 | 30.25% |

| 7 | Improper/Misuse—Overreliance on a Single Source (fraudulent use, dishonesty, unfiltered acceptance of results, incorrect application) | 90 | 28.66% |

| 8 | Incomplete Development of Skills (cognitive and non-cognitive) (lack of research skills, reduced academic performance, lack of spherical knowledge/thinking/understanding, problem-solving deficiency, lack of logical reasoning, weakened experiences) | 70 | 22.29% |

| 9 | Technology Dependence/Addiction (addiction to easiness, inability to function without AI) | 60 | 19.11% |

| 10 | Inequalities and Assessment/Grading Issues (effortless success, difficulty to prove one’ s credentials, reduced trust in the university and students’ degrees) | 35 | 11.15% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Athanassopoulos, S.; Tzavara, A.; Aravantinos, S.; Lavidas, K.; Komis, V.; Papadakis, S. Teacher Education Students’ Practices, Benefits, and Challenges in the Use of Generative AI Tools in Higher Education. Educ. Sci. 2026, 16, 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16020228

Athanassopoulos S, Tzavara A, Aravantinos S, Lavidas K, Komis V, Papadakis S. Teacher Education Students’ Practices, Benefits, and Challenges in the Use of Generative AI Tools in Higher Education. Education Sciences. 2026; 16(2):228. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16020228

Chicago/Turabian StyleAthanassopoulos, Stavros, Aggeliki Tzavara, Spyridon Aravantinos, Konstantinos Lavidas, Vassilis Komis, and Stamatios Papadakis. 2026. "Teacher Education Students’ Practices, Benefits, and Challenges in the Use of Generative AI Tools in Higher Education" Education Sciences 16, no. 2: 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16020228

APA StyleAthanassopoulos, S., Tzavara, A., Aravantinos, S., Lavidas, K., Komis, V., & Papadakis, S. (2026). Teacher Education Students’ Practices, Benefits, and Challenges in the Use of Generative AI Tools in Higher Education. Education Sciences, 16(2), 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16020228