Women’s Perspectives on Factors That Most Impacted Their Sense of Belonging in Undergraduate Active Learning Calculus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review & Theoretical Framing

2.1. Sense of Belonging

2.2. Factors Contributing to Sense of Belonging

2.2.1. Social Connectedness

2.2.2. Perceived Competence

2.2.3. Learning Environment

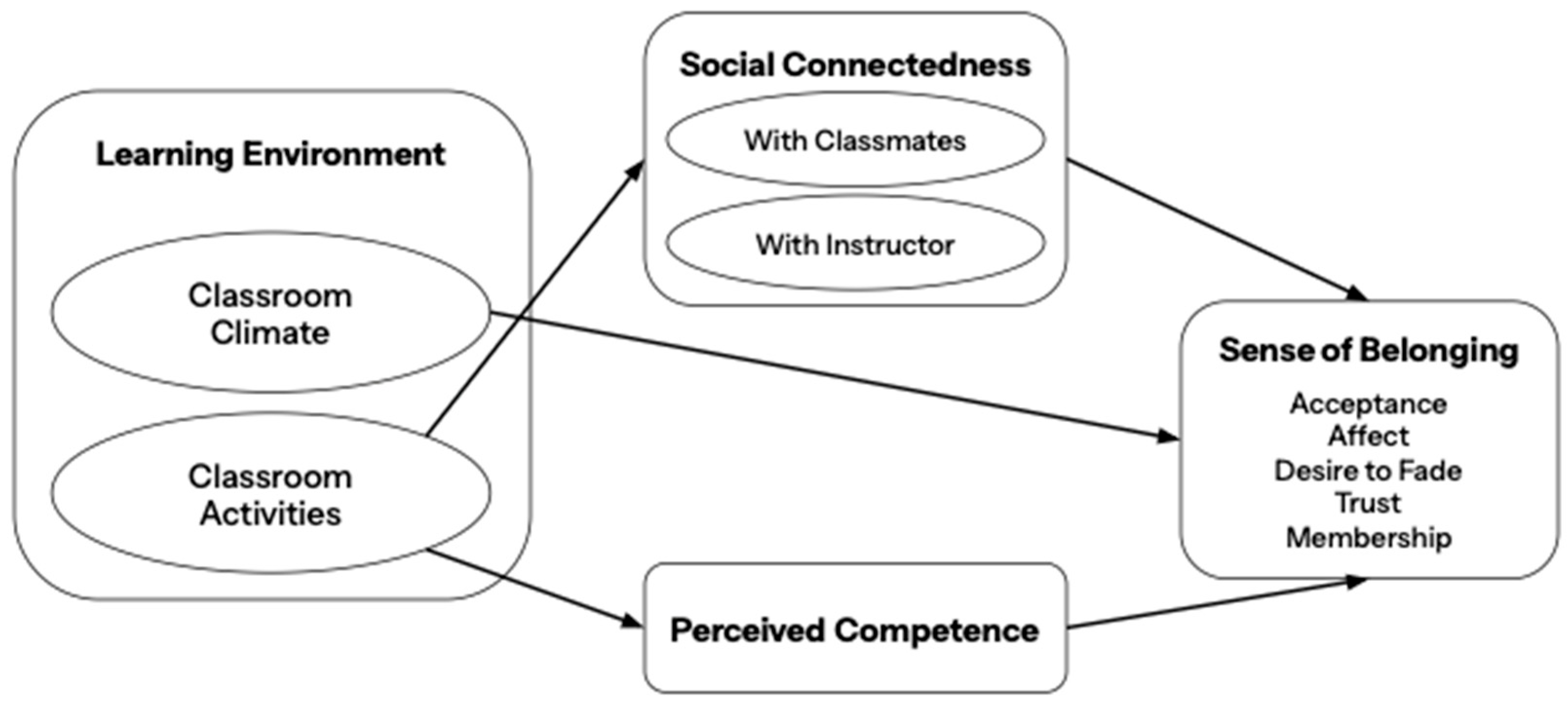

2.3. Hypothesized Theoretical Framework

3. Goals of the Current Study

My goal with this work is to share women’s perspectives with the hope of informing transformations in tertiary mathematics programs.How do women enrolled in a year-long active learning Calculus course rank and describe the impact of social connectedness, perceived competence, and the learning environment on their sense of belonging?

4. Methods

4.1. Setting and Participants

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Quantitative Results: Ranking of Contributing Factors’ Impact on Sense of Belonging

5.2. Qualitative Results: Explanations of Rankings of Factors Influencing Sense of Belonging

5.2.1. Social Connectedness with Classmates

She later reported, “Feeling connected to the people in the classroom setting is the most important to my sense of belonging because it is beneficial to know that they are sharing the experience with me.” Here, women expressed feeling like members of some larger group, and a sense of solidarity came with that. While not referring to a particular component of SB, these examples show how SC-C impacted participants’ SB more generally.Engaging with classmates makes me feel like I can relate to them and understand that everyone makes mistakes and that my classmates are also having the same experiences that I am. Having the opportunity to connect with them helps me feel like I am a part of the group and that we’re in it together.

These examples demonstrate the way that feeling SC-C helped participants feel comfortable and not stressed or discouraged, thus positively influencing the affect component of their SB.I feel like I am more comfortable being a math student when I am surrounded by people who struggle and learn math with me. No matter if I am doing well or poorly, if I am surrounded by people that have shared experiences I don’t feel discouraged.

5.2.2. Social Connectedness with the Instructor

These women all happened to choose both SC-I and PC as their top two factors influencing their SB. These responses express that SC-I contributed to their PC, which then impacted their SB.Connectedness with your instructor impacts your perceived competence. When your professor teaches you well, you will do better in the class. Also, when you feel good about what you know and feel confident in it, you have a better time in class.

5.2.3. Perceived Competence

Another (#92) reported feeling “less involved in the room” when she did not understand the content. When their PC was strong, participants reported wanting to engage and feeling like active participants. For at least some women, they need to feel competent in order to engage in the class at all. Thus, for some women, the extent to which they engaged and participated in class seemed to depend in part on their PC.If you feel like you don’t belong in the class based on not understanding the material, I feel like it doesn’t matter as much what your peers, professor, or class activities look like because you yourself give up in a way.

5.2.4. Classroom Climate

5.2.5. Classroom Activities

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

7.1. Recommendations

7.2. Areas for Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| STEM | Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics |

| SB | Sense of belonging |

| SC | Social connectedness |

| SC-C | Social connectedness with classmates |

| SC-I | Social connectedness with instructor |

| PC | Perceived competence |

References

- Adelman, H. S., & Taylor, L. (2002). Classroom climate. In S. W. Lee, P. A. Lowe, & E. Robinson (Eds.), Encyclopedia of school psychology (pp. 304–312). SAGE Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Aji, C. A., & Khan, M. J. (2019). The impact of active learning on students’ academic performance. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 7, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderman, L. H. (2003). Academic and social perceptions as predictors of change in middle school students’ sense of school belonging. The Journal of Experimental Education, 72(1), 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaler, J. (1997). Reclaiming school mathematics: The girls fight back. Gender and Education, 9(3), 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S., Felner, R., Shim, M., Seitsinger, A., & Dumas, T. (2003). Middle school improvement and reform: Development and validation of a school-level assessment of climate, cultural pluralism, and school safety. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95, 570–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressoud, D. M. (2020). Opportunities for change in the first two years of college mathematics. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology, 82(5), 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressoud, D. M. (2023). Trends in math degrees. Available online: https://www.mathvalues.org/masterblog/trends-in-math-degrees (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Bui, Q. (2014). Who studies what? Men, women and college majors. Available online: https://www.npr.org/sections/money/2014/10/28/359419934/who-studies-what-men-women-and-college-majors (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Carlone, H. B., & Johnson, A. (2007). Understanding the science experiences of successful women of color: Science identity as an analytic lens. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 44(8), 1187–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. (2013). STEM attrition: College students’ paths into and out of STEM fields (NCES 2014-001). National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 47, 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cribbs, J. D., Hazari, Z., Sonnert, G., & Sadler, P. M. (2015). Establishing an explanatory model for mathematics identity. Child Development, 86(4), 1048–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danielson, M., & Björkman, I. (2025). Project-based learning in social innovation—Developing a sense of belonging in online contexts. Education Sciences, 15(7), 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Bois, B. (1983). Passionate scholarship: Notes on values, knowing, and method in feminist social science. In G. Bowles, & R. D. Klein (Eds.), Theories of women’s studies. Routledge and Kegan Paul. [Google Scholar]

- Eagan, K., Stolzenberg, E. B., Bates, A. K., Aragon, M. C., Suchard, M. R., & Rios-Aguilar, C. (2016). The American freshman: National norms fall 2015. Higher Education Research Institute, UCLA. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, J., Fosdick, B. K., & Rasmussen, C. (2016). Women 1.5 times more likely to leave stem pipeline after calculus compared to men: Lack of mathematical confidence a potential culprit. PLoS ONE, 11(7), e0157447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J., Kelton, M. L., & Rasmussen, C. (2013). Student perceptions of pedagogy and associated persistence in calculus. ZDM Mathematics Education, 46, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, I. M., Harvey, S. T., Buckley, L., & Yan, E. (2009). Differentiating classroom climate concepts: Academic, management, and emotional environments. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 4(2), 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(23), 8410–8415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, T., & Anderman, L. (2002, August 22–25). College freshmen’s classroom belonging: Relations to motivation and instructor practices [Poster session]. Annual Conference of the American Psychological Association, Chicago, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Frisby, B. N., & Martin, M. M. (2010). Instructor-student and student-student rapport in the classroom. Communication Education, 59(2), 146–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, S., & Sahmbi, G. (2024). Investigating the impact of active learning in large coordinated calculus courses. International Journal of Research in Undergraduate Mathematics Education, 11, 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillen-O’Neel, C., & Fuligni, A. (2013). A longitudinal study of school belonging and academic motivation across high school. Child Development, 84(2), 678–692. [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Good, C., Rattan, A., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Why do women opt out? Sense of belonging and women’s representation in mathematics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(4), 700–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, C. (2025). Direct and indirect influence of active learning on women’s sense of belonging in calculus. In S. Cook, B. Katz, & K. Melhuish (Eds.), Proceedings of the 27th annual conference on research in undergraduate mathematics education. SIGMAA on RUME. Available online: http://sigmaa.maa.org/rume/RUME27_Proceedings.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2026).

- Griffin, C., & Berk, D. (2023). What women want: Pedagogical approaches for promoting female students’ sense of belonging in undergraduate calculus. In E. Rueda, & C. Lowe-Swift (Eds.), Creating academic belonging for underrepresented students: Models and strategies for faculty success. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, C. R. (2023). Women’s sense of belonging in undergraduate calculus and the influence of (inter)active learning opportunities. Journal of Research in Science, Mathematics, and Technology Education, 6(2), 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerty, B. M., Williams, R. A., & Oe, H. (2002). Childhood antecedents of adult sense of belonging. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(7), 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R. M., & Sandler, B. R. (1982). The classroom climate: A chilly one for women? Association of American Colleges. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, R. M., & Sandler, B. R. (1984). Out of the classroom: A chilly campus climate for women? Association of American Colleges. [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann, L. R. M., Schofield, J. W., & Woods, R. L. (2007). Sense of belonging as a predictor of intentions to persist among African American and white first-year college students. Research in Higher Education, 48(7), 803–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, M., Richmond, J., Morrow, J., & Salomone, K. (2003). Investigating “sense of belonging” in first-year college students. Journal of College Student Retention, 4, 227–256. [Google Scholar]

- Hottinger, S. N. (2016). Inventing the mathematician. State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D. R. (2012). Campus racial climate perceptions and overall sense of belonging among racially diverse women in STEM majors. Journal of College Student Development, 53(2), 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E., Andrews-Larson, C., Keene, K., Melhuish, K., Keller, R., & Fortune, N. (2020). Inquiry and gender inequity in the undergraduate mathematics classroom. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 51(4), 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzinger, C., & Wilkinson, S. (1997). Validating women’s experience? Dilemmas in feminist research. Feminism and Psychology, 7(4), 566–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, M., & Laursen, S. L. (2014). Assessing long-term effects of inquiry-based learning: A case study from college mathematics. Innovative Higher Education, 39(3), 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuh, G., Cruce, T., Shoup, R., Kinzie, J., & Gonyea, R. (2008). Unmasking the effects of student engagement on first-year college grades and persistence. The Journal of Higher Education, 79(5), 540–563. [Google Scholar]

- Lahdenperä, J., & Nieminen, J. H. (2020). How does a mathematician fit in? A mixed-methods analysis of university students’ sense of belonging in mathematics. International Journal of Research in Undergraduate Mathematics Education, 6(3), 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahdenperä, J., Postareff, L., & Rämö, J. (2019). Supporting quality of learning in university mathematics: A comparison of two instructional designs. International Journal of Research in Undergraduate Mathematics Education, 5(1), 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K. L., & Hodges, S. D. (2015). Expanding the concept of belonging in academic domains: Development and validation of the ability uncertainty scale. Learning and Individual Differences, 37, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMahon, S., Carroll, A., & Gillies, R. M. (2020). Capturing the ‘vibe’: An exploration of the conditions underpinning connected learning environments. Learning Environments Research, 23, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maries, A., Whitcomb, K., & Singh, C. (2022). Gender inequities throughout STEM: Compared to men, women with significantly higher grades drop STEM majors. Journal of College Science Teaching, 51(3), 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A. J., & Dowson, M. (2009). Interpersonal relationships, motivation, engagement, and achievement: Yields for theory, current issues, and educational practice. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 327–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendick, H. (2006). Masculinities in mathematics. Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mesa, V., Burn, H., & White, N. J. (2015). Good teaching of calculus I. In D. M. Bressoud, V. Mesa, & C. L. Rasmussen (Eds.), Insights and recommendations from the MAA national study of college calculus (pp. 83–91). MAA Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, D. K., & Turner, J. C. (2006). Re-conceptualizing emotion and motivation to learn in classroom contexts. Educational Psychology Review, 18, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES). (2023). Diversity and STEM: Women, minorities, and persons with disabilities 2023 (Special Report NSF 23-315). National Science Foundation. Available online: https://nsf-gov-resources.nsf.gov/doc_library/nsf23315-report.pdf?VersionId=OfErRcu.MTEp_KCzcuAfyfIkh0cU_XQO (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Nguyen, K. A., Borrego, M., Finelli, C. J., DeMonbrun, M., Crockett, C., Tharayil, S., Shekhar, P., Waters, C., & Rosenberg, R. (2021). Instructor strategies to aid implementation of active learning: A systemic literature review. International Journal of STEM Education, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (1980). Predicting freshman persistence and voluntary dropout decisions from a theoretical model. The Journal of Higher Education, 51(1), 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST). (2012). Engage to excel: Producing one million additional college graduates with degrees in Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. The White House. [Google Scholar]

- Rainey, K., Dancy, M., Mickelson, R., Stearns, E., & Moller, S. (2018). Race and gender differences in how sense of belonging influences decisions to major in STEM. International Journal of STEM Education, 5(1), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainey, K., Dancy, M., Mickelson, R., Stearns, E., & Moller, S. (2019). A descriptive study of race and gender differences in how instructional style and perceived professor care influence decisions to major in STEM. International Journal of STEM Education, 6(1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, C., Apkarian, N., Hagman, J. E., Johnson, E., Larsen, S., & Bressoud, D. (2019). Characteristics of precalculus through calculus 2 programs: Insights from a national census survey. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 50(1), 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, C., & Ellis, J. (2013a). Students who switch out of calculus and the reasons they leave. In M. Martinex, & A. Castro Superfine (Eds.), Proceedings of the 35th annual meeting of the North American chapter of the international group for the psychology of mathematics education (pp. 457–464). University of Illinois at Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, C., & Ellis, J. (2013b). Who is switching out of calculus and why? In A. M. Lindmeier, & A. Heinze (Eds.), Proceedings of the 37th conference of the international group for the psychology of mathematics education (Vol. 4, pp. 73–80). PME. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, M., & McCullough, B. C. (1981). Mattering: Inferred significance and mental health among adolescents. Research in Community & Mental Health, 2, 163–182. [Google Scholar]

- Serenko, A., & Bontis, N. (2013). First in, best dressed: The presence of order-effect bias in journal ranking surveys. Journal of Infometrics, 7(1), 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, E., & Hewitt, N. M. (Eds.). (1997). Talking about leaving: Why undergraduates leave the sciences. Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Seymour, E., & Hunter, A.-B. (Eds.). (2019). Talking about leaving revisited: Persistence, relocation, and loss in undergraduate STEM education. Center for STEM Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, C. A., & Sax, L. J. (2011). Major selection and persistence for women in STEM. New Directions for Institutional Research, 14(7), 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, D., Battishtich, V., Kim, D., & Watson, M. (1997). Teacher practices associated with students’ sense of the classroom as a community. Social Psychology of Education, 1, 235–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, Y., & Croft, T. (2016). Understanding undergraduate disengagement from mathematics: Addressing alienation. International Journal of Educational Research, 79, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speer, J. D. (2023). Bye bye Ms. American Sci: Women and the leaky STEM pipeline. Economics of Education Review, 93, 102371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayhorn, T. L. (2019). College students’ sense of belonging: A key to educational success for all students (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Thacker, I., Seyranian, V., Madva, A., Duong, N. T., & Beardsley, P. (2022). Social connectedness in physical isolation: Online teaching practices that support under-represented undergraduate students’ feelings of belonging and engagement in STEM. Education Sciences, 12, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theobald, E. J., Hill, M. J., Tran, E., Agrawal, S., Arroyo, E. N., Behling, S., Chambwe, N., Cintrón, D. L., Cooper, J. D., Dunster, G., Grummer, J. A., Hennessey, K., Hsiao, J., Iranon, N., Jones, L., 2nd, Jordt, H., Keller, M., Lacey, M. E., Littlefield, C. E., … Freeman, S. (2020). Active learning narrows achievement gaps for underrepresented students in undergraduate science, technology, engineering, and math. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(12), 6476–6483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoman, D. B., Arizaga, J. A., Smith, J. L., Story, T. S., & Soncuya, G. (2014). The grass is greener in non-science technology, engineering, and math classes: Examining the role of competing belonging to undergraduate women’s vulnerability to being pulled away from science. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 38(2), 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoman, D. B., Smith, J. L., Brown, E. R., Chase, J., & Lee, J. K. (2013). Beyond performance: A motivational experience model of stereotype threat. Educational Psychology Review, 25, 211–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinto, V. (1975). Dropout from higher education: A theoretical synthesis of recent research. Review of Educational Research, 45(1), 89–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanders, F. H. K., van der Veen, I., Dijkstra, A. B., & Maslowski, R. (2019). The influence of teacher-student and student-student relationships on societal involvement in Dutch primary and secondary schools. Theory and Research in Social Education, 48(1), 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. T., & Degol, J. L. (2017). Gender gap in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM): Current knowledge, implications for practice, policy, and future directions. Educational Psychology Review, 29, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, C. N., Duran, P., Castillo, A., Fuller, E., Potvin, G., & Kramer, L. (2023). The supportive role of active learning in a calculus course on low precalculus proficiency students. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 56(4), 561–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Definition | Sample Items |

|---|---|---|

| Acceptance | The extent to which students feel included, valued, and respected in the community | I feel accepted/I feel excluded |

| Affect | The extent to which students feel comfortable and calm versus nervous and tense | I feel comfortable/I feel anxious |

| Desire to Fade | The extent to which students feel like they want to fade into the background and not be noticed | I enjoy being an active participant/ I wish I could fade into the background and not be noticed |

| Trust | The extent to which students trust the instructor and features of the class to help them learn | I trust the instructor to be committed to helping me learn |

| Membership | The extent to which students feel like members of the community | I feel like part of the math community |

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnic/Racial Background | ||

| White | 24 | 83 |

| Black or African American | 1 | 3 |

| Hispanic or Latine | 2 | 7 |

| East Asian | 0 | 0 |

| South Asian | 1 | 3 |

| Southeast Asian | 1 | 3 |

| Major | ||

| STEM | 25 | 86 |

| Non-STEM/Undecided | 4 | 14 |

| Previous Calculus Experience | ||

| None | 13 | 45 |

| High School | 16 | 55 |

| College | 0 | 0 |

| Other Identifiers | ||

| First-generation | 3 | 10 |

| Current or former English Language Learner | 0 | 0 |

| International Student | 2 | 7 |

| None of the Above | 24 | 83 |

| Type of Impact | Code | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Indirect | Social Connectedness | Mentions connections with classmates or instructor, getting to know others |

| Perceived Competence | Mentions their learning or their understanding of the material | |

| Direct | Acceptance | Mentions feeling included or accepted versus excluded or lonely |

| Affect | Mentions feeling calm or comfortable versus anxious or nervous | |

| Desire to Fade/Engagement | Mentions actively participating or engaging versus fading into the background | |

| Trust | Mentions trusting the instructor to help them or believe in their potential | |

| Membership | Code not used |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Griffin, C. Women’s Perspectives on Factors That Most Impacted Their Sense of Belonging in Undergraduate Active Learning Calculus. Educ. Sci. 2026, 16, 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16020194

Griffin C. Women’s Perspectives on Factors That Most Impacted Their Sense of Belonging in Undergraduate Active Learning Calculus. Education Sciences. 2026; 16(2):194. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16020194

Chicago/Turabian StyleGriffin, Casey. 2026. "Women’s Perspectives on Factors That Most Impacted Their Sense of Belonging in Undergraduate Active Learning Calculus" Education Sciences 16, no. 2: 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16020194

APA StyleGriffin, C. (2026). Women’s Perspectives on Factors That Most Impacted Their Sense of Belonging in Undergraduate Active Learning Calculus. Education Sciences, 16(2), 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16020194