Linking Attitudes, Self-Efficacy, and Intentions for Inclusion Among Secondary Special Education Teachers: A Pooled Exploratory Factor Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Teachers’ Attitudes Toward Inclusive Education

2.2. Self-Efficacy for Inclusive Practices and Social Cognitive Theory

2.3. Behavioral Intentions and the Theory of Planned Behavior

2.4. Inclusive Readiness

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Participants and Sampling

3.3. Instrument

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Correlations Among Attitudes, Self-Efficacy and Intentions

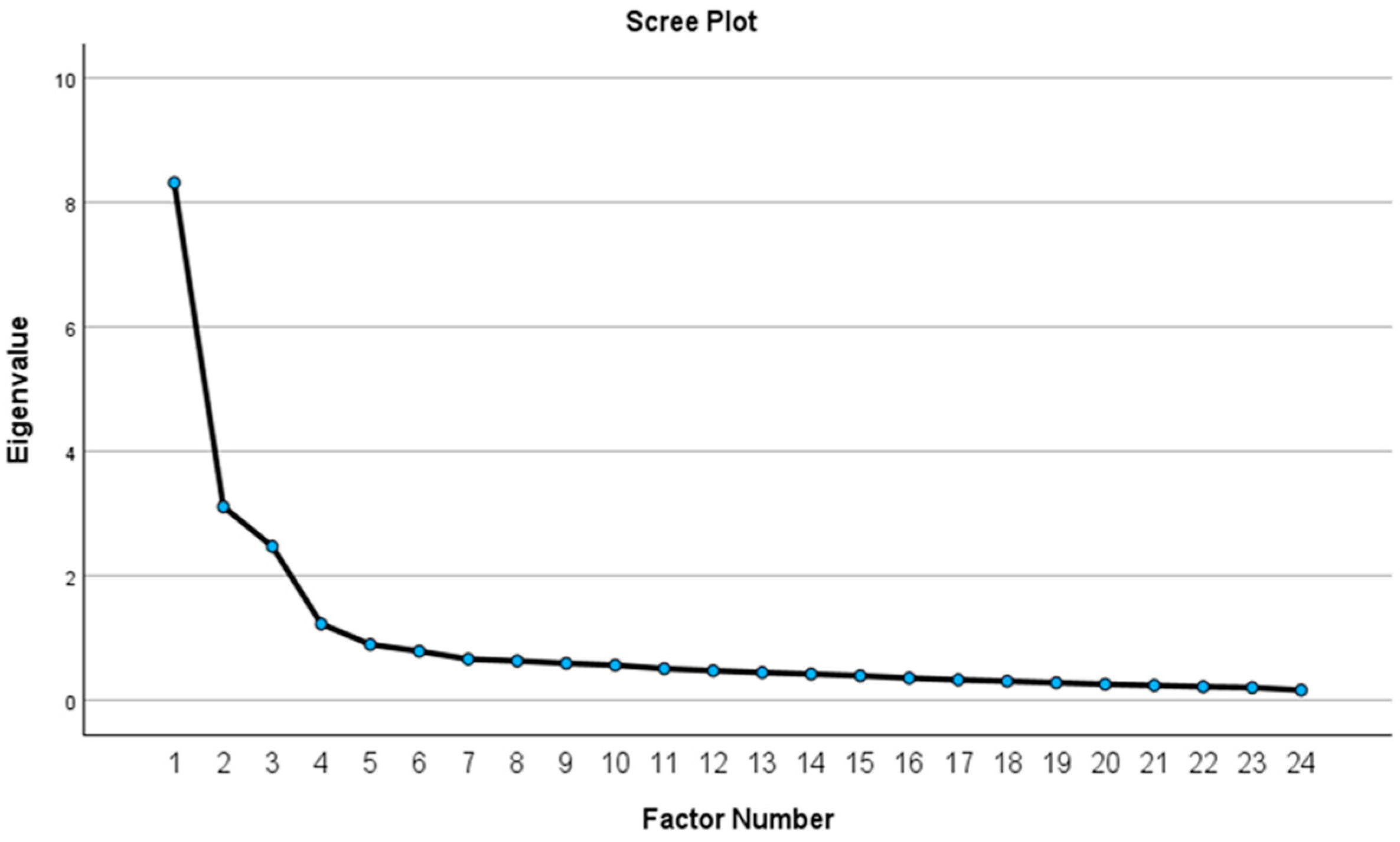

4.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

- Attitudes toward Inclusive Education (AIS)—consisting exclusively of AIS items (A1–A7), capturing teachers’ evaluative beliefs and feelings toward inclusive schooling.

- Intentions to Teach in Inclusive Classrooms (ITICS)—comprising ITICS items (B1, B3–B7), reflecting teachers’ intentions and willingness to enact inclusive teaching practices.

- Self-efficacy for Behavior Management (TEIP)—including TEIP items (C7–C12), representing teachers’ perceived capability to prevent and manage disruptive or challenging classroom behavior in inclusive settings.

- Self-efficacy for Collaboration and Professional Support (TEIP)—comprising TEIP items (C2, C15–C18), representing teachers’ perceived capability to collaborate with other professionals and support inclusive implementation.

4.3. Reliability Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Implications

7. Limitations

8. Conclusions

9. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIS | Attitudes toward Inclusive Education Scale |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| ITICS | Inclusive Classroom Teaching Intentions Scale |

| ML | Maximum Likelihood |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| RQ | Research Question |

| SEN | Special Educational Needs |

| TEIP | Teacher Efficacy for Inclusive Practices Scale |

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behavior |

Appendix A

| Instrument | Item | Exclusion Criterion (Trigger) |

|---|---|---|

| AIS | A8 | Primary factor loading < 0.35 |

| ITICS | B2 | Primary factor loading < 0.35 |

| TEIP | C1 | Primary factor loading < 0.35 |

| TEIP | C3 | Problematic cross-loading (secondary loading ≥ 0.35) |

| TEIP | C4 | Problematic cross-loading (secondary loading ≥ 0.35) |

| TEIP | C5 | Primary factor loading < 0.35 |

| TEIP | C6 | Primary factor loading < 0.35 |

| TEIP | C13 | Problematic cross-loading (secondary loading ≥ 0.35) |

| TEIP | C14 | Problematic cross-loading (secondary loading ≥ 0.35) |

| Instrument | Item Code | Item Wording | Pooled EFA Factor (ML/Oblimin) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AIS | A1 | Students with special educational needs benefit academically from being educated in inclusive classrooms. | Factor 1: Attitudes toward Inclusive Education |

| AIS | A2 | Inclusion promotes social acceptance of students with special educational needs. | Factor 1: Attitudes toward Inclusive Education |

| AIS | A3 | Teaching students with special educational needs in inclusive classrooms is educationally valuable. | Factor 1: Attitudes toward Inclusive Education |

| AIS | A4 | Inclusive schooling benefits all students, not only those with special educational needs. | Factor 1: Attitudes toward Inclusive Education |

| AIS | A5 | Teachers have a responsibility to support the inclusion of students with special educational needs. | Factor 1: Attitudes toward Inclusive Education |

| AIS | A6 | Inclusive education contributes positively to the school climate. | Factor 1: Attitudes toward Inclusive Education |

| AIS | A7 | Students with special educational needs should be educated alongside their peers whenever possible. | Factor 1: Attitudes toward Inclusive Education |

| ITICS | B1 | I am willing to teach students with special educational needs in inclusive classrooms. | Factor 2: Intentions to Teach in Inclusive Classrooms |

| ITICS | B3 | I intend to adapt my teaching to meet the needs of students with special educational needs. | Factor 2: Intentions to Teach in Inclusive Classrooms |

| ITICS | B4 | I plan to use inclusive instructional strategies in my teaching. | Factor 2: Intentions to Teach in Inclusive Classrooms |

| ITICS | B5 | I intend to collaborate with other professionals to support inclusion. | Factor 2: Intentions to Teach in Inclusive Classrooms |

| ITICS | B6 | I am willing to take responsibility for teaching students with diverse needs. | Factor 2: Intentions to Teach in Inclusive Classrooms |

| ITICS | B7 | I intend to implement inclusive practices in my daily teaching. | Factor 2: Intentions to Teach in Inclusive Classrooms |

| TEIP | C7 | I am confident in managing disruptive behavior in inclusive classrooms. | Factor 3: Self-efficacy for Behavior Management |

| TEIP | C8 | I can control disruptive behavior in the classroom. | Factor 3: Self-efficacy for Behavior Management |

| TEIP | C9 | I am able to calm a disruptive student. | Factor 3: Self-efficacy for Behavior Management |

| TEIP | C10 | I can prevent disruptive behavior before it occurs. | Factor 3: Self-efficacy for Behavior Management |

| TEIP | C11 | I can manage challenging behavior effectively | Factor 3: Self-efficacy for Behavior Management |

| TEIP | C12 | I am confident in dealing with behavior problems in inclusive classrooms. | Factor 3: Self-efficacy for Behavior Management |

| TEIP | C2 | I can collaborate effectively with other professionals to support students with special educational needs. | Factor 4: Self-efficacy for Collaboration and Professional Support |

| TEIP | C15 | I can work collaboratively with parents of students with special educational needs. | Factor 4: Self-efficacy for Collaboration and Professional Support |

| TEIP | C16 | I can cooperate with support staff to implement inclusive practices. | Factor 4: Self-efficacy for Collaboration and Professional Support |

| TEIP | C17 | I can coordinate effectively with specialists involved in inclusive education. | Factor 4: Self-efficacy for Collaboration and Professional Support |

| TEIP | C18 | I feel confident working within multidisciplinary teams to support inclusion. | Factor 4: Self-efficacy for Collaboration and Professional Support |

| Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0.71 | |||

| A2 | 0.47 | |||

| A3 | 0.63 | |||

| A4 | 0.60 | |||

| A5 | 0.77 | |||

| A6 | 0.72 | |||

| A7 | 0.65 | |||

| B1 | 0.55 | |||

| B3 | 0.70 | |||

| B4 | 0.58 | |||

| B5 | 0.79 | |||

| B6 | 0.78 | |||

| B7 | 0.80 | |||

| C2 | 0.42 | |||

| C7 | 0.75 | |||

| C8 | 0.88 | |||

| C9 | 0.92 | |||

| C10 | 0.77 | |||

| C11 | 0.73 | |||

| C12 | 0.57 | |||

| C15 | 0.74 | |||

| C16 | 0.63 | |||

| C17 | 0.68 | |||

| C18 | 0.40 |

| Fit Index | Value |

|---|---|

| Chi-square (χ2) | 358.882 |

| Degrees of Freedom (df) | 186 |

| Significance (p-value) | <0.001 |

| Items | MSA |

|---|---|

| Overall MSA | 0.91 |

| Adapt the curriculum to meet the needs of a student with learning difficulties | 0.96 |

| Collaborate with the parents of a struggling student | 0.92 |

| Collaborate with colleagues to find ways to support a struggling student | 0.92 |

| Attend professional development programs to teach students with diverse needs | 0.90 |

| Discuss with a student showing problematic behavior to improve collaboration | 0.94 |

| Include students with significant needs in various classroom activities | 0.93 |

| Adapt assessment activities to match the learning profile of a struggling student | 0.91 |

| Believe that all students can be educated in mainstream classrooms | 0.83 |

| Believe inclusion has academic benefits for all students | 0.86 |

| Believe all students can learn if teachers differentiate the curriculum | 0.90 |

| Am satisfied teaching low-achieving students alongside others | 0.88 |

| Am excited to teach students with different abilities | 0.89 |

| Am pleased that inclusion helps me become a better teacher | 0.92 |

| Am happy to have included students needing assistance in daily classroom activities | 0.93 |

| Can provide alternative explanations or examples when students are confused | 0.89 |

| Feel confident in preventing disruptive behavior before it occurs | 0.91 |

| Can manage disruptive behavior in the classroom | 0.90 |

| Can calm a student who is being noisy | 0.90 |

| Can guide students to follow classroom rules | 0.92 |

| Feel confident dealing with physically aggressive students | 0.94 |

| Can clearly express behavioral expectations to students | 0.94 |

| Can collaborate with other professionals (e.g., aides, special educators) | 0.90 |

| Can collaborate with professionals to design programs for students with SEN | 0.87 |

| Feel confident informing others about laws and policies on inclusion | 0.93 |

References

- Adams, D., Mohamed, A., Moosa, V., & Shareefa, M. (2023). Teachers’ readiness for inclusive education in a developing country: Fantasy or possibility? Educational Studies, 49(6), 896–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M. (2020). Promoting inclusion and equity in education: Lessons from international experiences. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 6(1), 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (2006). Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(4), 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (2020). The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2(4), 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalky, H. A., & Alrabiah, A. H. (2024). Predictors of teachers’ intention to implement inclusive education. Children and Youth Services Review, 158, 107457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arboiz, A. C., & Aoanan, G. O. (2024). Teacher efficacy and attitude in inclusive education as predictors of readiness for inclusive education: An explanatory sequential design. EPRA International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, 10(5), 838–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Burak, Y., Ahmetoglu, E., & Sakalli-Gümüş, S. (2025). Teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion and views on self-efficacy and classroom practices regarding inclusive education. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 26(1), e70047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camedda, D., & Tarantino, G. (2023, August 21–22). Teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education: A systematic review of the literature. [Paper presentation]. European Conference on Educational Research (ECER 2023), Glasgow, UK. Available online: https://eera-ecer.de/ecer-programmes/conference/28/contribution/54637 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Chow, W. S. E., de Bruin, K., & Sharma, U. (2024). A scoping review of perceived support needs of teachers for implementing inclusive education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 28(13), 3321–3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. W. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 10(1), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desombre, C., Delaval, M., & Jury, M. (2021). Influence of social support on teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 736535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierendonck, C., Poncelet, D., & Tinnes-Vigne, M. (2024). Why teachers do (or do not) implement recommended teaching practices? An application of the theory of planned behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1269954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dignath, C., Rimm-Kaufman, S., van Ewijk, R., & Kunter, M. (2022). Teachers’ beliefs about inclusive education and insights on what contributes to those beliefs: A meta-analytic study. Educational Psychology Review, 34, 2609–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmers, E., Baeyens, D., & Petry, K. (2019). Attitudes and self-efficacy of teachers towards inclusion in higher education. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 35(2), 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrigar, L. R., Wegener, D. T., MacCallum, R. C., & Strahan, E. J. (1999). Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods, 4(3), 272–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. (2018). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (5th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Foykas, E., Raikou, N., Beazidou, E., & Karalis, T. (2025). Transformative potential in special education: How perceived success, training, exposure and experience contribute to teacher readiness for inclusive practice. Education Sciences, 15(11), 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülsün, İ., Malinen, O.-P., Yada, A., & Savolainen, H. (2025). Applying the theory of planned behaviour to examine teachers’ intentions to teach in inclusive classrooms and their inclusive practices. British Educational Research Journal, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid, M. S., & Mohamed, N. I. A. (2021). Empirical investigation into teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education: A study of future faculty of Qatari schools. Cypriot Journal of Educational Science, 16(2), 580–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellenic Republic. (2008). Law 3699/2008: Special education and training of persons with disabilities or with special educational needs (Government Gazette A’ 199/02-10-2008). Hellenic Republic.

- Hellenic Republic. (2012). Law 4074/2012: Ratification of the United Nations convention on the rights of persons with disabilities and the optional protocol to the convention on the rights of persons with disabilities (Government Gazette A’ 88/11-04-2012). Hellenic Republic.

- Herzig Johnson, S. (2023). The role of teacher self-efficacy in the implementation of inclusive practices. Journal of School Leadership, 33(5), 516–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hick, P., Matziari, A., Mintz, J., Ó Murchú, F., Cahill, K., Hall, K., Curtin, C., & Solomon, Y. (2019). Initial teacher education for inclusion: Final report to the National Council for Special Education. National Council for Special Education. Available online: https://ncse.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/04611_NCSE-Initial-Teacher-Education-RR27.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Jia, Q., Martínez-Hernández, C., & Peña-Martínez, J. (2025). Mapping the integration of theory of planned behavior and self-determination theory in education: A scoping review on teachers’ behavioral intentions. Education Sciences, 15(11), 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H. F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika, 39(1), 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, N., McCoy, S., & O’Higgins Norman, J. (2023). A whole education approach to inclusive education: An integrated model to guide planning, policy, and provision. Education Sciences, 13(9), 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiana, I. F., & Hendriani, W. (2018). Teaching efficacy in inclusive education (IE) in Indonesia and other Asia, developing countries: A systematic review. Journal of Education and Learning (EduLearn), 12(2), 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupers, E., de Boer, A., Bakker, A., de Jong, F., & Minnaert, A. (2024). Explaining teachers’ behavioural intentions towards differentiated instruction for inclusion: Using the theory of planned behavior and the self-determination theory. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 39(4), 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrothanasis, K., Zervoudakis, K., & Xafakos, E. (2021). Secondary special education teachers’ beliefs towards their teaching self-efficacy. Preschool and Primary Education, 9(1), 28–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouchritsa, M., Romero, A., Garay, U., & Kazanopoulos, S. (2022). Teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education at Greek secondary education schools. Education Sciences, 12(6), 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudhar, G., Ertesvåg, S. K., & Pakarinen, E. (2024). Patterns of teachers’ self-efficacy and attitudes toward inclusive education associated with teacher emotional support, collective teacher efficacy, and collegial collaboration. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 39(3), 446–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narkun, Z., & Smogorzewska, J. (2019). Studying self-efficacy among teachers in Poland is important: Polish adaptation of the Teacher Efficacy for Inclusive Practice (TEIP) scale. Exceptionality Education International, 29(2), 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissim, M., & Shamma, F. (2025). Supporting teacher professionalism for inclusive education: Integrating cognitive, emotional, and contextual dimensions. Education Sciences, 15(10), 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, M. P., Cuskelly, M., Pedersen, S. J., & Rayner, C. S. (2021). Applying the theory of planned behaviour in assessments of teachers’ intentions towards practicing inclusive education: A scoping review. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 36(4), 577–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, E., & Colum, M. (2021). Newly qualified teachers and inclusion in higher education: Policy, practice and preparation. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Leadership Studies, 2(1), 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichenberg, M., Thunberg, G., Holmer, E., Palmqvist, L., Samuelsson, J., Lundälv, M., Mühlenbock, K., & Heimann, M. (2023). Will an app-based reading intervention change how teachers rate their teaching self-efficacy beliefs? A test of social cognitive theory in Swedish special educational settings. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1184719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, P. (2022). Best practices for your exploratory factor analysis: A factor tutorial. Revista de Administração Contemporânea, 26(6), e210085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahli Lozano, C., Wüthrich, S., Baumli, N., Sharma, U., Loreman, T., & Forlin, C. (2023). Development and validation of a short form of the Teacher Efficacy for Inclusive Practices Scale (TEIP-SF). Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 23(4), 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahli Lozano, C., Wüthrich, S., Kullmann, H., Knickenberg, M., Sharma, U., Loreman, T., Romano, A., & Avramidis, E. (2024). How do attitudes and self-efficacy predict teachers’ intentions to use inclusive practices? A cross-national comparison between Canada, Germany, Greece, Italy, and Switzerland. Exceptionality Education International-Special Issue on Inclusive Education: Canada’s Connection to the World, 34(1), 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savolainen, H., Malinen, O. P., & Schwab, S. (2022). Teacher efficacy predicts teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion—A longitudinal cross-lagged analysis. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 26(9), 958–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepadi, M. D. (2025). Teachers’ understanding of implementing inclusion in mainstream classrooms in rural areas. Education Sciences, 15(7), 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shareef, M. A., Akram, M. S., Malik, F. T., Kumar, V., Dwivedi, Y. K., & Giannakis, M. (2023). An attitude–behavioral model to understand people’s behavior towards tourism during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Business Research, 161, 113839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, U., & Jacobs, D. K. (2016). Predicting in-service educators’ intentions to teach in inclusive classrooms in India and Australia. Teaching and Teacher Education, 55(3), 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, U., Loreman, T., & Forlin, C. (2012). Measuring teacher efficacy to implement inclusive practices. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 12(1), 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics (7th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. (n.d.). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities: Greece (ratification status). United Nations Treaty Collection. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Available online: https://treaties.un.org/pages/viewdetails.aspx?chapter=4&clang=_en&mtdsg_no=iv-15&src=treaty (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Urton, K., Wilbert, J., Krull, J., & Hennemann, T. (2023). Factors explaining teachers’ intention to implement inclusive practices in the classroom: Indications based on the theory of planned behaviour. Teaching and Teacher Education, 132, 104225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuni, S., Novembli, M. S., & Hasanah, N. (2024). Self-efficacy: Readiness of teachers in inclusive schools. Al-Ishlah: Journal of Pendidikan, 16(3), 3018–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T., Deng, M., & Tian, G. (2025). Facilitating teachers’ inclusive education intentions: The roles of transformational leadership, school climate, and teacher efficacy. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 12, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcock, S., Sharma, U., Subban, P., & Hitches, E. (2022). Teacher self-efficacy and inclusive education practices: Rethinking teachers’ engagement with inclusive practices. Teaching and Teacher Education, 117, 103802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, R. L., & Whittaker, T. A. (2006). Scale development research: A content analysis and recommendations for best practices. The Counseling Psychologist, 34(6), 806–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yada, A., Leskinen, M., Savolainen, H., & Schwab, S. (2022). Meta-analysis of the relationship between teachers’ self-efficacy and attitudes toward inclusive education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 109, 103521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | M | SD | AIS1 | AIS2 | ITICS1 | ITICS2 | TEIP1 | TEIP2 | TEIP3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIS1 | 5.32 | 1.14 | — | 0.63 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.30 |

| AIS2 | 5.71 | 1.2 | — | 0.51 | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.34 | 0.49 | |

| ITICS1 | 5.93 | 0.98 | — | 0.79 | 0.55 | 0.32 | 0.51 | ||

| ITICS2 | 6.04 | 1.06 | — | 0.51 | 0.29 | 0.47 | |||

| TEIP1 | 5.07 | 0.58 | — | 0.57 | 0.72 | ||||

| TEIP2 | 4.92 | 0.71 | — | 0.62 | |||||

| TEIP3 | 5.09 | 0.63 | — |

| Items | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Uniqueness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0.71 | 0.55 | |||

| A2 | 0.47 | 0.71 | |||

| A3 | 0.63 | 0.60 | |||

| A4 | 0.60 | 0.61 | |||

| A5 | 0.77 | 0.37 | |||

| A6 | 0.72 | 0.41 | |||

| A7 | 0.65 | 0.42 | |||

| B1 | 0.55 | 0.49 | |||

| B3 | 0.70 | 0.46 | |||

| B4 | 0.58 | 0.54 | |||

| B5 | 0.79 | 0.43 | |||

| B6 | 0.78 | 0.37 | |||

| B7 | 0.80 | 0.27 | |||

| C2 | 0.42 | 0.68 | |||

| C7 | 0.75 | 0.39 | |||

| C8 | 0.88 | 0.24 | |||

| C9 | 0.92 | 0.21 | |||

| C10 | 0.77 | 0.33 | |||

| C11 | 0.73 | 0.45 | |||

| C12 | 0.57 | 0.47 | |||

| C15 | 0.74 | 0.38 | |||

| C16 | 0.63 | 0.49 | |||

| C17 | 0.68 | 0.43 | |||

| C18 | 0.40 | 0.59 |

| Factor | Observed Eigenvalue | Random Eigenvalue | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6.85 | 1.48 | Retained |

| 2 | 3.42 | 1.40 | Retained |

| 3 | 2.78 | 1.35 | Retained |

| 4 | 1.96 | 1.30 | Retained |

| 5 | 0.88 | 1.27 | Not retained |

| 6 | 0.74 | 1.24 | Not retained |

| 7 | 0.62 | 1.21 | Not retained |

| Factor | Initial Eigenvalues: Total | Initial Eigenvalues: % of Variance | Initial Eigenvalues: Cumulative % | Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings: Total | Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings: % of Variance | Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings: Cumulative % | Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings: Total | Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings: % of Variance | Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings: Cumulative % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8.32 | 34.69 | 34.69 | 7.91 | 32.94 | 32.94 | 4.15 | 17.31 | 17.31 |

| 2 | 3.12 | 12.99 | 47.68 | 2.77 | 11.53 | 44.46 | 4.06 | 16.91 | 34.21 |

| 3 | 2.48 | 10.33 | 58.00 | 2.01 | 8.38 | 52.85 | 3.50 | 14.60 | 48.82 |

| 4 | 1.23 | 5.14 | 63.14 | 0.79 | 3.30 | 56.14 | 1.76 | 7.33 | 56.14 |

| Factors | Items | Cronbach’s α | McDonald’s ω |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Attitudes toward Inclusive Education | A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, A6, A7 | 0.89 | 0.89 |

| 2. Intentions to Teach in Inclusive Classrooms | B1, B3, B4, B5, B6, B7 | 0.91 | 0.91 |

| 3. Self-efficacy for Behavior Management | C7, C8, C9, C10, C11, C12 | 0.86 | 0.86 |

| 4. Self-efficacy for Collaboration and Professional Support | C2, C15, C16, C17, C18 | 0.74 | 0.76 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Beazidou, E.; Raikou, N.; Foykas, E. Linking Attitudes, Self-Efficacy, and Intentions for Inclusion Among Secondary Special Education Teachers: A Pooled Exploratory Factor Analysis. Educ. Sci. 2026, 16, 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16020195

Beazidou E, Raikou N, Foykas E. Linking Attitudes, Self-Efficacy, and Intentions for Inclusion Among Secondary Special Education Teachers: A Pooled Exploratory Factor Analysis. Education Sciences. 2026; 16(2):195. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16020195

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeazidou, Eleftheria, Natassa Raikou, and Evaggelos Foykas. 2026. "Linking Attitudes, Self-Efficacy, and Intentions for Inclusion Among Secondary Special Education Teachers: A Pooled Exploratory Factor Analysis" Education Sciences 16, no. 2: 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16020195

APA StyleBeazidou, E., Raikou, N., & Foykas, E. (2026). Linking Attitudes, Self-Efficacy, and Intentions for Inclusion Among Secondary Special Education Teachers: A Pooled Exploratory Factor Analysis. Education Sciences, 16(2), 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16020195