Promoting Student Flourishing and Enhancing Staff Capability: “You Matter”—A Co-Designed Approach to Embedding Wellbeing in University Curriculum

Abstract

1. Introduction

Research Questions

- What should an embedded mental health and wellbeing literacy program look like from the perspectives of key stakeholders, students and staff?

- What are the key factors that influence successful implementation of a curriculum-embedded wellbeing program in university settings?

- What insights can be drawn from the pilot intervention to inform future refinement and broader application of the program?

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

- Phase 1: Co-Design and Needs Analysis. This initial phase encompassed the foundational steps of the framework, including (1) Examining background knowledge, (2) Planning and coordination, (3) Shaping focus through interactive, participant engaged co-design workshops encompassing sharing and collaboration and (4) Assessing the collected data from workshops and a student survey to analyse key wellbeing needs.

- Phase 2: Pilot Program Implementation and Evaluation. This action-oriented phase initiated the PAR cycle’s core loop. The work included (5) Designing the program prototype based on Phase 1 data. (6) Presentation of the prototype to academic facilitators, followed by (7) Pilot testing in real-world settings. The evaluation of the program’s feasibility and reception represented a secondary cycle of data assessment, providing the essential information for subsequent refinement.

- Phase 3: Program Refinement and Toolkit Development. This final phase completed the iterative cycle by applying pilot evaluation findings to refine program materials and develop the final Facilitator’s Toolkit, aligning with the modification and implementation steps of the co-design framework.

2.2. Phase 1: Co-Design and Needs Analysis

2.2.1. Participants and Recruitment

2.2.2. Co-Design Workshops Approach

2.2.3. Student Needs Survey

2.3. Phase 2: Pilot Program Implementation and Evaluation

2.3.1. Pilot Implementation

- (1)

- In-person Synchronous Workshop: Facilitated by an academic with a counsellor co-facilitator.

- (2)

- Online Synchronous Workshop: A live, online session facilitated by an academic with a counsellor co-facilitator.

- (3)

- Embedded Asynchronous: Pre-recorded video with an in-class activity.

- (4)

- Fully Asynchronous: Online module including pre-recorded video and self-paced activity shared with students via email.

2.3.2. Data Collection for Pilot Evaluation

- Student Feedback Survey: A post-pilot online survey was distributed to all participating students to assess the program’s perceived usefulness and reception. A total of 61 undergraduate students completed the survey.

- Staff Interviews: Semi-structured interviews were conducted with five of the 10 academic facilitators to explore their experiences, perceptions of student engagement, and recommendations for improvement. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

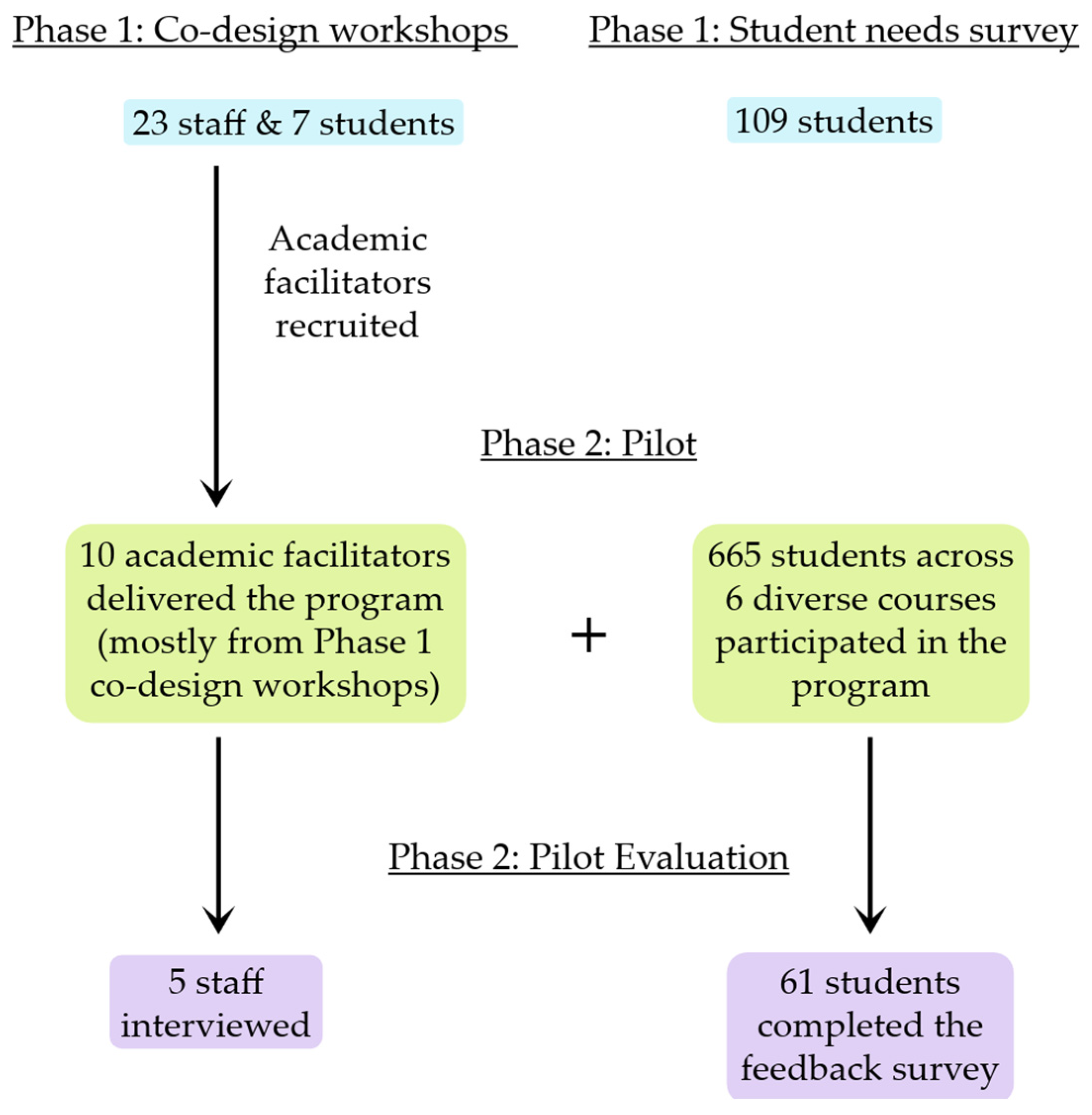

2.3.3. Overview of Participant Flow and Numbers (Phases 1 and 2)

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Phase 3: Program Refinement and Toolkit Development

3. Results

3.1. Findings from Phase 1: Co-Design Workshops and Needs Analysis Survey

3.1.1. Co-Design Workshops

“I think amongst international students like mental health is sometimes considered a bit taboo within their culture, so they do feel a little scared to bring it up and they don’t sometimes recognize the severity of their mental health concerns.”

3.1.2. Student Survey Corroboration

3.2. Translating Phase 1 Findings into Pilot Program Design

3.3. Findings from Phase 2: Pilot Program Evaluation

3.3.1. Student Reception and Feedback

3.3.2. Academic Facilitator Experience: The ‘Dual Benefit’ of an Embedded Program

“Yes, academics are important… However, your mental health is just as important, and it’s not a weakness or it’s not a distraction to talk about mental health.”

3.4. Phase 3: Program Refinement and Toolkit Development

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Practice and Future Directions

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID | Coronavirus Disease |

| PAR | Participatory Action Research |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

References

- Arnett, J. J., Žukauskienė, R., & Sugimura, K. (2014). The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18 & 29 years: Implications for mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(7), 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2024). Health of young people. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/health-of-young-people (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Baik, C., Larcombe, W., & Brooker, A. (2016). A framework for promoting student mental wellbeing in universities. Available online: https://unistudentwellbeing.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/MCSHE-Student-Wellbeing-Framework_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Boman, J., Lindsay, B., Bernier, E., & Boyce, M. A. (2025). Fostering student wellbeing in the postsecondary teaching and learning environment. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 49(2), 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonehill, A., & Iordan, M. F. (2025). Relational pedagogy and inclusion in higher education. International Relations, Political Science and Journalism, 1, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. SAGE Publications Ltd. Available online: https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/thematic-analysis/book248481 (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Brewster, L., Jones, E., Priestley, M., Wilbraham, S., Spanner, L., & Hughes, G. (2021). ‘Look after the staff and they would look after the students’ cultures of wellbeing and mental health in the university setting. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 46, 548–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cage, E., Stock, M., Sharpington, A., Pitman, E., & Batchelor, R. (2018). Barriers to accessing support for mental health issues at university. Studies in Higher Education, 45, 1637–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, F., Blank, L., Cantrell, A., Baxter, S., Blackmore, C., Dixon, J., & Goyder, E. (2022). Factors that influence mental health of university and college students in the UK: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- DeMarchis, J., Friedman, L., & Garg, K. E. (2021). An ethical responsibility to instill, cultivate, and reinforce self-care skills. Journal of Social Work Education, 58, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulfer, N., Gowing, A., & Mitchell, J. (2024). Building belonging in online classrooms: Relationships at the core. Teaching in Higher Education, 30, 1024–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraku, Z. H., Davis, H., & Hamiti, E. (2023). Mental health, study skills, social support, and barriers to seeking psychological help among university students: A call for mental health support in higher education. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1220614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, C., Ferradás, M.-D.-M., Regueiro, B., Rodríguez, S., Valle, A., & Núñez, J. (2020). Coping strategies and self-efficacy in university students: A person-centered approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudet, S., Marchand, I., Bujaki, M., & Bourgeault, I. (2021). Women and gender equity in academia through the conceptual lens of care. Journal of Gender Studies, 31, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Torrano, D., Ibrayeva, L., Sparks, J., Lim, N., Clementi, A., Almukhambetova, A., Nurtayev, Y., & Muratkyzy, A. (2020). Mental health and well-being of university students: A bibliometric mapping of the literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E., Priestley, M., Brewster, L., Wilbraham, S. J., Hughes, G., & Spanner, L. (2021). Student wellbeing and assessment in higher education: The balancing act. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 46(3), 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, M., & Erdem, C. (2021). Students’ well-being and academic achievement: A meta-analysis study. Child Indicators Research, 14, 1743–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L. (2007). Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing. American Psychologist, 62(2), 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L. M., Dhingra, S. S., & Simoes, E. J. (2010). Change in level of positive mental health as a predictor of future risk of mental illness. American Journal of Public Health, 100(12), 2366–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimiecik, J. (2011). Exploring the promise of eudaimonic well-being within the practice of health promotion: The “How” is as Important as the “What”. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12(5), 769–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, N., Pickett, W., McNevin, S. H., Bowie, C. R., Rivera, D., Keown-Stoneman, C., Harkness, K., Cunningham, S., Milanovic, M., Saunders, K. E. A., Goodday, S., Duffy, A., & U-Flourish Student Well-Being and Academic Success Research Group. (2021). Mental health need of students at entry to university: Baseline findings from the U-flourish student well-being and academic success study. Early interveNTIOn in Psychiatry, 15(2), 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, B., Bailie, J., Dickinson, H., Hewitt, B., Cooper, E., Kavanagh, A., Aitken, Z., & Shields, M. (2025). Codesign is the zeitgeist of our time, but what do we mean by this? A scoping review of the concept of codesign in collaborative research with young people. Health Research Policy and Systems, 23, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J. M. (2010). Stigma and student mental health in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 29(3), 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P., & Barraclough, S. (2025). Redesigning academic warning conversations with first-year engineering students: Experiences of an Academic Dean. European Journal of Engineering Education, 50, 1033–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McTaggart, R., Nixon, R., & Kemmis, S. (2017). Critical participatory action research. In L. L. Rowell, C. D. Bruce, J. M. Shosh, & M. M. Riel (Eds.), The palgrave international handbook of action research (pp. 21–35). Palgrave Macmillan US. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I. S., Louw, A., & Ernstzen, D. (2017). Physiotherapy students’ perceptions of the dual role of the clinical educator as mentor and assessor: Influence on the teaching–learning relationship. South African Journal of Physiotherapy, 73(1), 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Rodríguez, F., & Pérez-Mármol, J. (2019). The role of anxiety, coping strategies, and emotional intelligence on general perceived self-efficacy in university students. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyimbili, F., & Nyimbili, L. (2024). Types of purposive sampling techniques with their examples and application in qualitative research studies. British Journal of Multidisciplinary and Advanced Studies, 5(1), 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okanagan Charter. (2015). Okanagan charter: An international charter for health promoting universities & colleges. Available online: https://www.chpcn.ca/okanagan-charter (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Olivera, P. C., Gordillo, P. G., Mejía, H. N., La Fuente Taborga, I., Chacón, A. G., & Unzueta, A. S. (2023). Academic stress as a predictor of mental health in university students. Cogent Education, 10, 2232686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orygen. (2020). Australian university mental health framework. Orygen. Available online: https://www.orygen.org.au/Orygen-Institute/University-Mental-Health-Framework/Framework/University-Mental-Health-Framework-full-report (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Paton, L. W., Tiffin, P. A., Barkham, M., Bewick, B. M., Broglia, E., Edwards, L., Knowles, L., McMillan, D., & Heron, P. N. (2023). Mental health trajectories in university students across the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from the Student Wellbeing at Northern England Universities prospective cohort study. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1188690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestley, M., Broglia, E., Hughes, G., & Spanner, L. (2021). Student perspectives on improving mental health support services at university. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 22(1), 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queensland Health. (2025). Your mental wellbeing. Available online: https://www.qld.gov.au/health (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Slimmen, S., Timmermans, O., Mikołajczak-Degrauwe, K., & Oenema, A. (2022). How stress-related factors affect mental wellbeing of university students A cross-sectional study to explore the associations between stressors, perceived stress, and mental wellbeing. PLoS ONE, 17(11), e0275925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofija, E., Harris, N., Phung, D., Sav, A., & Sebar, B. (2020). Does flourishing reduce engagement in unhealthy and risky lifestyle behaviours in emerging adults? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofija, E., Harris, N., Sebar, B., & Phung, D. (2021). Who are the flourishing emerging adults on the urban east coast of Australia? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofija, E., Reyes Bernard, N., Wiseman, N., & Harris, N. (2024). Co-designing a nature play program for culturally and linguistically diverse children and primary carers: Implications for practice. Wellbeing, Space and Society, 6, 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upsher, R., Nobili, A., Hughes, G., & Byrom, N. (2022). A systematic review of interventions embedded in curriculum to improve university student wellbeing. Educational Research Review, 37, 100464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbina-Garcia, A. (2020). What do we know about university academics’ mental health? A systematic literature review. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 36(5), 563–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winzer, R., Lindberg, L., Guldbrandsson, K., Sidorchuk, A., & Patton, B. (2018). Effects of mental health interventions for students in higher education are sustainable over time: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PeerJ, 6, e4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. M., & Joseph, S. (2010). The absence of positive psychological (eudemonic) well-being as a risk factor for depression: A ten year cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 122(3), 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Program Component | Mean (SD) | Positive Reception (% Rated “Extremely” = 5 or “Very” = 4 Useful) |

|---|---|---|

| Academic facilitator’s sharing of personal wellbeing strategies | 4.07 (0.77) | 77% |

| University Counsellor’s sharing of personal wellbeing strategies (face-to-face or video) | 4.03 (0.91) | 71% |

| Content of the workshop | 3.80 (0.73) | 66% |

| Support resources provided * | 3.93 (0.87) | 66% |

| Self-Care Plan Worksheet | 3.77 (0.90) | 59% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chiang, L.; Campbell, R.C.; Hafey, K.; Nam, H.M.; Sofija, E. Promoting Student Flourishing and Enhancing Staff Capability: “You Matter”—A Co-Designed Approach to Embedding Wellbeing in University Curriculum. Educ. Sci. 2026, 16, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010080

Chiang L, Campbell RC, Hafey K, Nam HM, Sofija E. Promoting Student Flourishing and Enhancing Staff Capability: “You Matter”—A Co-Designed Approach to Embedding Wellbeing in University Curriculum. Education Sciences. 2026; 16(1):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010080

Chicago/Turabian StyleChiang, Lisa, Russell C. Campbell, Katelyn Hafey, Hye Min Nam, and Ernesta Sofija. 2026. "Promoting Student Flourishing and Enhancing Staff Capability: “You Matter”—A Co-Designed Approach to Embedding Wellbeing in University Curriculum" Education Sciences 16, no. 1: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010080

APA StyleChiang, L., Campbell, R. C., Hafey, K., Nam, H. M., & Sofija, E. (2026). Promoting Student Flourishing and Enhancing Staff Capability: “You Matter”—A Co-Designed Approach to Embedding Wellbeing in University Curriculum. Education Sciences, 16(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010080