Social Cohesion Through Education: A Case Study of Singapore’s National Education System

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Context

1.2. Research Problem and Significance

1.3. Research Question and Objectives

- Examine how Singapore evolved into a diverse society historically, and the nature of nation-building in the context of colonial legacies.

- Investigate the state’s early educational responses to post-independence socioeconomic challenges and the educational policy principles adopted.

- Analyze the state’s educational responses to emerging challenges of globalization.

- Identify the role of education in managing social diversity and building social cohesion, and derive potential lessons from Singapore’s educational experiences.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Diversity and Social Cohesion

2.2. Education and Nation-Building

2.3. Globalization and Education Policy

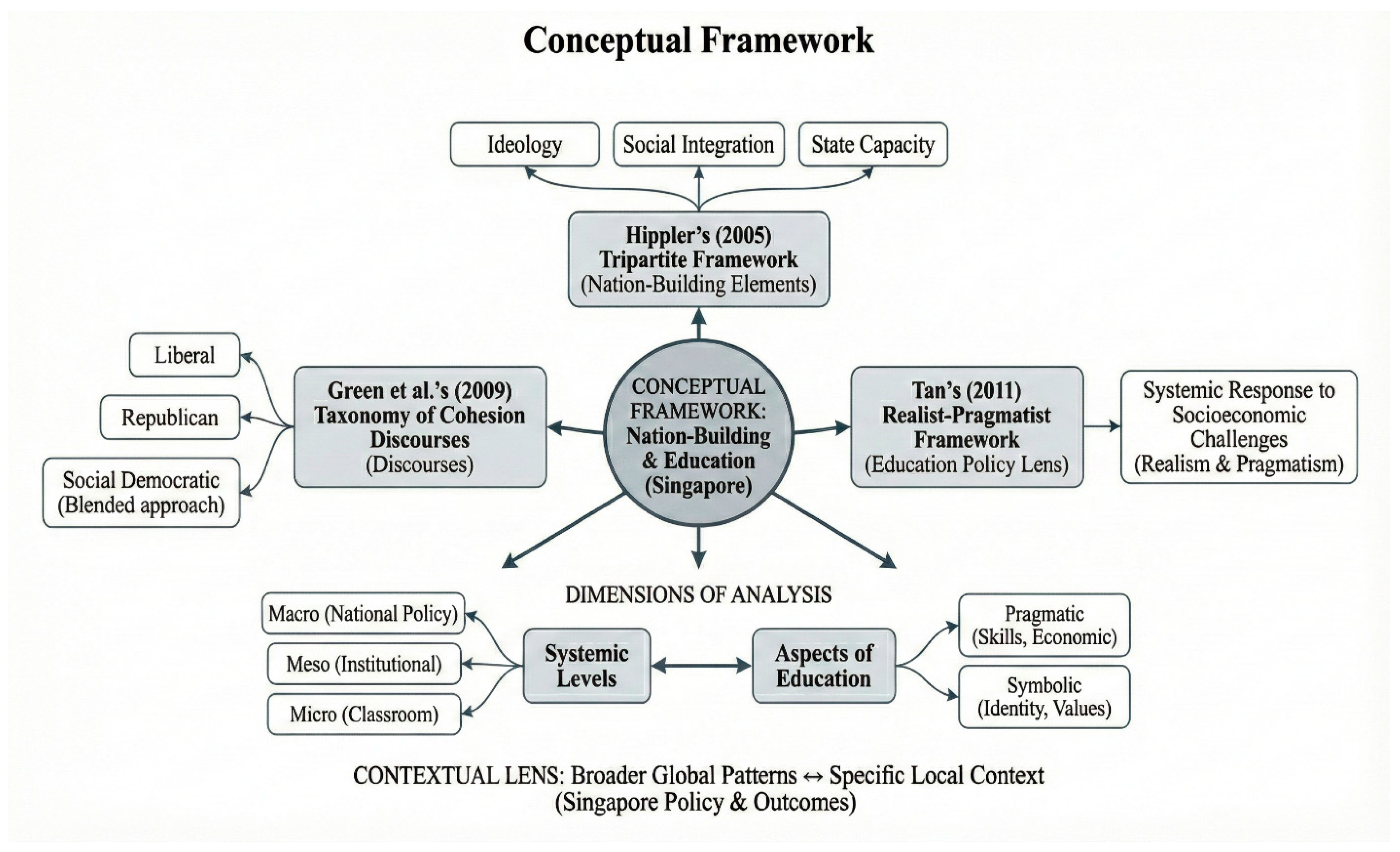

2.4. Conceptual Framework

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design: Case Study Approach

3.2. Participant Selection and Sampling

3.3. Data Collection Methods

3.4. Data Analysis Approach

4. Findings

4.1. Colonial Legacies and Social Diversity

4.1.1. Emergence of a Plural Society

Singapore was a plural society because, in the Singaporean case, the multiracial and the multiethnic designations did not fully capture the extent of vertical divisions; Chinese were largely Buddhist or Taoist, they ate pork, they were largely business oriented; Indians were largely Hindu, they ate pork but no beef, their religious practices were considered to be different and economic specialization was different; the Malays ate beef but no pork and they were largely Muslims. In a sense, when one looks at Singapore, especially in terms of occupation, religion, and culture, it was a plural society.

The crucial historical fact was migration between the 1860s and the turn of the century, largely of Chinese economic migrants. Indians were brought by the British Raj, particularly to work in civil services and railroad services. The Chinese were more interested in business rather than civil services. Malays were largely associated with fishing and farming, and the colonial power held the view that Malays were the owners of the land and that their cultural practices should not be disturbed. Neither had they provided much education because they were here to extract profits as much as possible. Colonial policies thus facilitated migration while reinforcing ethnic divisions through differentiated treatment and limited investment in integrated education.

4.1.2. Colonial Education and Social Division

At the turn of the Second World War, the education system reflected the social, ethnic, and cultural divisions of society; Chinese students attended Chinese-medium schools, and Indians largely attended English-medium schools. Thus, in general, schools were not designed to form a unified society… There was a degree of hostility, especially between the Chinese-educated and English-educated. The English-educated were supported by the colonial powers, creating a sense of separateness that fueled hostility. Consequently, the school and education system became a vehicle for hostility, social division and misunderstanding.

4.2. Post-Independence Educational Reforms

4.2.1. Addressing the Challenge of a Nation Without a State

The early leaders recognized the need to establish a unified national identity. For this purpose, the state took measures to instill in the people a sense that they should identify themselves as Singaporeans rather than as Chinese, Malays, Indians, and others.

One can see the history of civic and citizenship education, and these were the mechanisms for building, in successive generations, a sense of what it means to be Singaporean. The state realized that when a child goes home, the home is often very ethnically centered. The parents or grandparents came from China; their schooling was conducted there, and their socialization also took place in China. They cannot be the role models for Singapore’s citizenship. School has to be the centre of citizenship education. Then, schools had to become an instrument for nation-building, citizenship education, and social cohesion, in addition to being an academic institution.

4.2.2. Foundational Principles: Multiculturalism, Multilingualism, and Meritocracy

The bilingual policy was designed to maintain ethnic cultural heritage while building a common language for communication across groups and with the global economy. It was a pragmatic decision recognizing that language is both an identity marker and a practical tool.

In Singapore, education is viewed as an investment rather than an expense. The state viewed education as a vehicle for nation-building, producing a competent, adaptive, and productive workforce while promoting social cohesion among the various ethnic groups.

4.3. Multilingualism and Language Policy

4.3.1. English as Lingua Franca

The choice of English as the first language was motivated by practical considerations, as it is and has been the language of commerce, science, technology, and international intercourse. Emotionally, the choice might have been Chinese given the majority population, but that would have created tremendous resentment among minority groups and limited Singapore’s global engagement. English was ethnically neutral, the language of no local group and therefore not privileging any ethnic community.

At a historically important time, Singapore had an elite leadership that was up to the challenges. The state has been very strong in meeting the needs of the survival period, where the political elite leadership had to make some fundamental decisions… English became not just the language of education but the language of administration, commerce, and social mobility.

4.3.2. Mother Tongue Education

The bilingual policy is more complex than it appears. It’s not really about maintaining home languages, but about standardizing ethnic languages, Mandarin for all Chinese, regardless of dialect, and Tamil for Indians, regardless of their actual linguistic background. It serves nation-building by creating standardized ethnic categories.

4.4. Meritocracy and Equal Opportunity

Meritocracy is more than an educational principle in Singapore. It’s a social compact. The state promises that if you work hard and perform well, you will succeed regardless of your ethnic background. This was crucial in a multiethnic society where ethnic preferences could have torn the nation apart.

Meritocracy has become a double-edged sword. While it initially opened opportunities, it now risks becoming a system that perpetuates inequality. Students from privileged families have access to better enrichment opportunities, tuition, and exam preparation. Although the system appears meritocratic, advantages tend to accumulate.

Meritocracy isn’t perfect, but the alternatives are worse. Ethnic quotas would create resentment and undermine the idea that we succeed together as Singaporeans. The challenge is to make meritocracy truly equal by addressing the factors that prevent some students from realizing their full potential.

4.5. Visionary Leadership and Pragmatism

4.5.1. Leadership Vision and Political Will

The leadership understood from day one that Singapore had nothing except its people and its location. Investing in education was an essential requirement; it was a matter of existential significance. That clarity drove policy decisions and resource allocation.

The political leadership was crucial in shaping the first set of policies addressing economic, social, and political challenges. So the state has been very strong in order to meet the needs of the survival period, where the political elite leadership had to take some fundamental decisions to fix the issues of economic stability, and to have enough resources.

4.5.2. Realist-Pragmatist Philosophy

Singapore’s approach is ‘what works’. Leaders study global examples, adapt promising practices to the local context, implement carefully, monitor results, and adjust as needed. There’s no ideology preventing borrowing from different systems, selective adoption based on evidence of effectiveness.

4.6. Globalization and 21st Century Competencies

4.6.1. The Thinking Schools, Learning Nation Vision

The world was changing rapidly. Singapore couldn’t compete on cost; other nations had cheaper labor. We needed to compete on innovation, creativity, and knowledge creation. That required a different kind of education, one that develops thinking skills and dispositions for continuous learning.

4.6.2. National Identity Versus Global Citizenship

We need students who are rooted in Singapore, understand our history and challenges, and feel connected to the nation. But they also need to be globally aware, able to work across cultures, and comfortable in international contexts. It’s not either-or but both.

In a way, Singapore’s diversity is a global advantage. Our students grow up navigating multiple cultures, languages, and perspectives. That prepares them well for the multicultural global environment. The skills for managing diversity at home can be applied to managing diversity internationally.

4.6.3. Continuing Adaptation

Education policy in Singapore is never static. There’s continuous review, refinement, and adjustment. What worked in the 1960s won’t work now. What works now may not work in 2030. The commitment is to continue learning, improving, and adapting to new realities while maintaining the core values of social cohesion and equal opportunity.

5. Discussion

6. Implications

7. Conclusions

8. Future Research Directions

9. Study Limitations

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abinales, P. A., Noboru, I., & Akio, T. (2005). Dislocating the nation-state: Globalization in Asia and Africa. Trans Pacific Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alesch, D. J., Arendt, L. A., & Petak, W. J. (2012). Dynamic contexts and public policy implementation. In Natural hazard mitigation policy. Environmental hazards. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexiu, T. M., & Sorde, T. (2011). How to turn difficulties into opportunities: Drawing from diversity to promote social cohesion. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 21(1), 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K. T. (2015). The discursive construction of lower-tracked students: Ideologies of meritocracy and the politics of education. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 23, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J. A. (2017). Failed citizenship and transformative civic education. Educational Researcher, 46(7), 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourouh, O. C. (2007). Ethnic diversity and the question of national identity in Iraq. The International Journal of Diversity in Organizations, Communities and Nations, 7(5), 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, M., & Lee, W. O. (2001). Education and political transition: Themes and experiences in East Asia. Comparative Education Research Centre, University of Hong Kong. [Google Scholar]

- Britannica. (2025). Singapore—Multicultural, diverse, cosmopolitan. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/place/Singapore/The-people (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Bush, K. D., & Saltarelli, D. (2000). The two faces of education in ethnic conflict: Towards a peace-building education for children. UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, J. K. S. (2010). Teachers’ responses to curriculum policy implementation: Colonial constraints for curriculum reform. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 9(2), 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Statistics Singapore. (2024). Population trends 2024. Available online: https://www.singstat.gov.sg/-/media/files/publications/population/population2024.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Dimmock, C., & Goh, J. W. P. (2011). Transforming Singapore schools: The economic imperative, government policy and school principalship. In International handbook of leadership for learning (pp. 225–241). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, L. A. (Ed.). (2008). Religious diversity in Singapore. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, D. R. (2010). Beyond assimilation and multiculturalism: A critical review of the debate on managing diversity. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 11(3), 251–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gál, E. (2024). Investing in infants: Child protection and nationalism in Transylvania during dualism and the interwar period. Nationalities Papers, 52(3), 536–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinathan, S. (1980). Moral education in a plural society: A Singapore case study. International Review of Education, 26(2), 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinathan, S. (2001). Globalization, the state and education policy in Singapore. In M. Bray, & W. O. Lee (Eds.), Education and political transition: Themes and experiences in East Asia (pp. 21–36). Comparative Education Research Centre, University of Hong Kong. [Google Scholar]

- Gopinathan, S. (2007). Globalisation, the Singapore developmental state and education policy: A thesis revisited. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 5(1), 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradstein, M., & Justman, M. (2002). Education, social cohesion, and economic growth. The American Economic Review, 92(4), 1192–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A. (1997). Education, globalization and the nation state. Macmillan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Green, A., Janmaat, G., & Han, C. (2009). Regimes of social cohesion. Centre for Learning and Life Chances in Knowledge Economies and Societies. [Google Scholar]

- Green, A., Preston, J., & Janmaat, J. G. (2006). Education, equality and social cohesion: A comparative analysis. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, M., & Fee, L. K. (1995). The politics of nation building and citizenship in Singapore. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hippler, J. (2005). Nation-building: A key concept for peaceful conflict transformation? Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo-López, C., Mendive, S., & Castro, D. C. (2025). Monolingual early childhood educators teaching multilingual children: A scoping review. Education Sciences, 15(7), 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiely, R. (2007). The new political economy of development: Globalization, imperialism, hegemony. Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laurence, J. (2011). The effect of ethnic diversity and community disadvantage on social cohesion: A multi-level analysis of social capital and interethnic relations in UK communities. European Sociological Review, 27(1), 70–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W. O., Brown, P., Goodwin, A. L., & Green, A. (2023). International handbook on education development in Asia-Pacific. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Low, E. L. (2023). Education in a democratic and meritocratic society: Moving beyond thriving to flourishing. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 31(107). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Peláez, A., Aguilar-Tablada, M. V., Erro-Garcés, A., & Pérez-García, R. M. (2021). Superdiversity and social policies in a complex society: Social challenges in the 21st century. Current Sociology, 70(2), 166–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y., Liu, D., & Qu, Y. (2022). Revisiting social reproduction theory: Exploring the influence of economic and cultural capital on students’ achievement in China. International Journal of Educational Research, 116, 102082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickelson, R. A., & Nkomo, M. (2012). Integrated schooling, life course outcomes, and social cohesion in multiethnic democratic societies. Review of Research in Education, 36(1), 197–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, K. H., & Ku, Y. W. (2010). Social cohesion in Greater China: Challenges for social policy and governance. World Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Molina, A. (2021). Education, segregation and social cohesion. In School segregation and social cohesion in Santiago: Perspectives from the chilean experience (pp. 13–25). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutalib, H. (2002). The socioeconomic dimensions in Singapore’s quest for security and stability. Pacific Affairs, 75(1), 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachayeva, D. R. (2025). The role of secondary education institutions in the formation of national identity. «Педагoгикалық өлшемдер» ғылыми–практикалық журналы, 1(1), 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2018). The future of education and skills: Education 2030. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiga, Y. Y. (2015). Multiculturalism on its head: Unexpected boundaries and new migration in Singapore. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 16(4), 947–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, C. (2015). On building and rebuilding nations. In The power of education. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Print, M. (2013). Conceptualizing competences for democratic citizenship. In Civic education and competences for engaging citizens in democracies (pp. 149–162). SensePublishers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, M. (2004). Social policy in East and Southeast Asia: Education, health, housing, and income maintenance. Routledge Curzon. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakellariou, C. (2003). Rates of return to investments in formal and technical/vocational education in Singapore. Education Economics, 11(1), 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, W., Ainley, J., Fraillon, J., Losito, B., Agrusti, G., & Friedman, T. (2018). Becoming citizens in a changing world: IEA international civic and citizenship education study 2016 international report. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer, E. R. (2006). Promoting social cohesion through education: Case studies and tools for using textbooks and curricula. The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Siddique, S. (2001). Social cohesion and conflict in South Asia. In N. J. Colletta, T. G. Lim, & A. Kelles-Viitanem (Eds.), Social cohesion and conflict prevention in Asia: Managing diversity through development (pp. 1–22). The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D. (2010). Doing qualitative research (3rd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S., McFarland, D. A., van Tubergen, F., & Maas, I. (2016). Ethnic composition and friendship segregation: Differential effects for adolescent natives and immigrants. American Journal of Sociology, 121(4), 1223–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, J. (2006). Explaining the economic success of Singapore: The developmental worker as the missing link. Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, C. (2011). Philosophical perspectives on educational reforms in Singapore. In W. Choy, & C. Tan (Eds.), Education reforms in Singapore: Critical perspectives (pp. 13–33). Pearson Education South Asia. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, C., & Gopinathan, S. (2021). Education policy and the pandemic in Singapore. In F. M. Reimers (Ed.), Primary and secondary education during COVID-19 (pp. 287–310). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Taulaulelei, E., & Green, N. C. (2022). Supporting educators’ professional learning for equity pedagogy: The promise of open educational practices. Journal for Multicultural Education, 16(5), 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolhuter, C. C., Potgieter, F. J., & van der Walt, J. L. (2012). The capability of national education systems to address ethnic diversity. Koers: Bulletin for Christian Scholarship = Koers: Bulletin vir Christelike Wetenskap, 77(2), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T. C. (2023). The evolution of Singapore’s Chinese school education. Malaysian Journal of Chinese Studies, 12(2), 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications (Vol. 6). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Zajda, J. (2009). Nation-building, identity and citizenship education: Introduction. In J. Zajda, H. Daun, & L. J. Saha (Eds.), Nation-building, identity and citizenship education: Cross cultural perspectives (pp. 1–11). Springer. [Google Scholar]

| Dimension | Key Policy Mechanism | Theoretical Connection |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Integration | Unified National Schools: Replacing separate vernacular schools with a single national system to facilitate inter-ethnic interaction. | State Capacity (Hippler): The state’s ability to centralize infrastructure to physically bring diverse groups together. |

| Symbolic Integration | Bilingual Policy & National Narratives: Establishing English as a neutral lingua franca while maintaining “Mother Tongues” for cultural identity. | Ideology (Hippler)/Republican Discourse (Green et al.): Creating a shared national identity while respecting distinct cultural roots. |

| Instrumental Integration | Meritocracy & Economic Alignment: Education serves as an investment in economic survival and social mobility, based on ability rather than ethnicity. | Realist-Pragmatist (Tan): Prioritizing economic survival and practical outcomes over abstract ideology to legitimize the state. |

| Normative Integration | Citizenship Education (National Education): Inculcating shared values (e.g., tolerance, harmony) and national loyalty through the curriculum. | Social Integration (Hippler): The deliberate socialization of citizens into a cohesive “imagined community.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Karim, S. Social Cohesion Through Education: A Case Study of Singapore’s National Education System. Educ. Sci. 2026, 16, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010081

Karim S. Social Cohesion Through Education: A Case Study of Singapore’s National Education System. Education Sciences. 2026; 16(1):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010081

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarim, Shahid. 2026. "Social Cohesion Through Education: A Case Study of Singapore’s National Education System" Education Sciences 16, no. 1: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010081

APA StyleKarim, S. (2026). Social Cohesion Through Education: A Case Study of Singapore’s National Education System. Education Sciences, 16(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010081