Abstract

Teaching practice has long been considered a fundamental and integral part of any teacher education programme, but also very demanding for novice teachers when they are confronted with the reality of the classroom, for the first time in many cases. Teacher educators aim to allow student teachers to experience practice opportunities reflective of their many potential real-world future teaching scenarios, including, for example, teaching online through video conferencing tools or virtual reality. One such mode is teaching in chatrooms, using written language only, which is the focus of this paper. The aims of this research are therefore to investigate the use of corpus based reflective practice (CBRP) using a (written) chatroom corpus with student teachers and evaluate this approach through an exploration of their recounted perceptions. To do this, we conduct a preliminary corpus-based analysis of some of the more salient features of the student teacher chatroom corpus and examine how these align with the student teachers’ reported perceptions. Secondly, we aim to identify and evaluate the nature of the (spoken) discussions in the post-chatroom teaching experience interactions between the teacher educator and student teachers with reference to reflective practice engagement.

1. Introduction

Teaching practice is a fundamental but demanding part of any teacher education programme, particularly for those encountering the classroom as a teacher for the first time (Butler & Cuenca, 2012). In former times, student teachers had to contend with the complexity of traditional face-to-face classrooms as part of their practice experiences. The affordances of technology, combined with the forced initial push to technology-mediated/online classrooms during Covid lockdowns and its lingering impact, now means that teacher educators are challenged with trying to generate a wider range of ‘classroom’ exposures (Adnan et al., 2024). An example of this is chatroom teaching using written language only. Although this mode of pedagogic interaction is not entirely new (Yuan, 2003), and has been reported in the literature as perhaps best used in supplementary ways (Coetzee et al., 2014; Hamano-Bunce, 2011), it is likely here to stay for the immediate future in a world where chat is very much normalised, and will likely to continue to have an impact given the developments in the field of artificial intelligence (AI) (Chen et al., 2023; Tyen et al., 2024). For these reasons, the post-lockdown teaching practice we afford students on the MA in TESOL programme offered in our institution (the University of Limerick) includes a small element of chatroom teaching, as well as online, hybrid and face-to-face experiences. This chatroom teaching practice is the focus of investigation for the present paper.

As chatroom teaching can be new to some, and can feel somewhat unnatural to others, it is vital that student teachers are well-prepared and receive appropriate support and induction in advance of this exposure, and equally, have good opportunities to engage in reflective practice to help deconstruct and learn from their own experiences and the experiences of others. To this end, we have engaged Corpus-based Reflective Practice (CBRP, using a corpus as the basis of evidence and discussion for reflections and improvements) (Farr & Leńko-Szymańska, 2023) using the Teacher-Student Chatroom Corpus (Caines et al., 2020, 2022) to help prepare student teachers for their chatroom teaching practice and also to retrospectively critique their engagements and interactions. In this paper, we recount the findings from these pedagogic interventions with student teachers and share their reported perceptions of these experiences. The research is guided by the following two main research questions:

- What are student teacher experiences of teaching in written synchronous chatroom mode as evidenced in both their shared reflective discussions and through a corpus-based analysis of the chatroom transcripts?

- What is the nature of the reflective discussions with reference to Farr and Farrell’s (2025) evaluation criteria for reflective practice engagement: description, connections and comparisons, evidence, critique, reflection for action?

2. Theory and Literature

2.1. Reflective Practice and Language Teacher Education

The research reported in the current paper focuses on the reflective practices of student teachers using chatroom teaching as the focus for reflection. Reflective practice can target any aspect of classroom interactions and practices, and as such can delve into a multitude of fields (SLA, classroom language, classroom management, materials, tasks etc.). It would be impossible to go into each of these in detail in the current section, plus the focus of the paper is not on the individual components of classroom practice but more on the nature of the reflective practice of our student teachers and the corpus-based evidence for this, as per the technological and teacher education focus of the special issue. As such, we chose to limit our discussion in this short section to the practice-oriented components of teacher education and the theory of reflective practice as a concept, while integrating other types of relevant literature references in the relevant results and discussion sections later in the paper.

It has long been acknowledged in theoretical and practical ways that to become a teacher, an individual needs to develop a range of understandings and skills. Dewey (1904) was one of the first to theorise the importance of the development of both theoretical understandings and practical skills for successful growth on the journey to becoming a teacher. Shulman (1986) articulated a range of teacher competencies in what he called teacher knowledge. These include content knowledge (for example, English, Maths, Science), pedagogic knowledge (knowing about teaching methodologies and classroom skills), and pedagogic content knowledge (the most appropriate pedagogic techniques to teach the specific subject that you are teaching). Later, the notion of technological knowledge was isolated and added to these three (Mishra & Koehler, 2006), and more recently contextual knowledge was added (Mishra, 2019). As teacher educators, we are cognizant in our curriculum design to grant a focus to each of these areas to support our student cohorts. Pedagogic knowledge, which can be understood theoretically to some extent, inevitably needs aligned classroom practice for holistic development. Hence, teaching practice is a core component in the vast majority of teacher education programmes and an aspect that student teachers highly value (Farr & Karlsen, forthcoming). In fact, student teachers often express a desire to have even more opportunities for practice during their teacher formation (Papageorgiou et al., 2018), and novice teachers have reported on a lack of such opportunities as one of the causes for potential early teacher burnout (Seralp & Griffiths, 2025). Teacher education programmes offer various types of what Dewey (1904) would have called laboratory type practice (controlled to some extent), or what are also known collectively as pedagogies of practice (Grossman et al., 2009; McDonald et al., 2013). In other words, practice opportunities that are very close to real teaching contexts but may be scaffolded or supported by teacher educators or other teachers in ways to prevent full exposure or high risk for these student teachers while they are immersed in the learning process. To benefit most from practice opportunities, student teachers engage in what is known as reflective practice (Dewey, 1933; Holdo, 2022), a type of systematic and focussed reflection about their teaching before, during or after it occurs, in order to inform and improve future teaching.

Reflective practice has indeed become a mainstay of development across many professions, such as nursing, education, and human resources. It originates in ancient times, often associated with the Socratic method, ‘a dialectical method that employs critical inquiry to undermine the plausibility of widely-held doctrine’ (Brickhouse & Smith, 2000, p. 53). Dewey is credited with embracing and advocating related practices for educational contexts, and sees reflection as an emancipator from routine activity (Dewey, 1933). To create and maintain a focus for reflective practice, some type of evidence, or data, is required (T. S. C. Farrell, 2016; Walsh & Mann, 2015). This could be in the form of a video recording of classroom practice, or an analysis of a written curriculum or lesson plan. In the case of the present study, the evidence we use is the corpus (written transcriptions) of the chatroom teaching interactions. These become the evidence on which the reflective practice is based. In the framework they propose for the integration of corpus linguistics into language teacher education programmes, Farr and Leńko-Szymańska (2023) identify corpus-based reflective practice (CBRP) as one of the dimensions to facilitate teacher development, using relevant corpora, for example, of classroom discourse, including the teachers’ own classroom interactions packaged and searchable as a corpus. Once the data/evidence for reflective practice is available in this way, it can be manipulated to analyse and understand the classroom discourse, spoken or written (as is the case for a chatroom lesson), in order to critique it appropriately (Farr, 2022). The corpus can be used in quantitative ways (for example, to search for all of the question words used by the teachers), or in more qualitative ways (Tyne, 2023) to help understand subtle contextual factors. Such approaches can also be combined with video-viewing reflections aided by technology for additional interpretative and ethnographic accuracy (Sert et al., 2025). These reflections on action (Schön, 1983) should, in theory, provide a roadmap for the teacher to improve future practices.

2.2. Teaching Languages in (Human-to-Human) Synchronous Text-Based Chatrooms

With the advent and rapid growth of artificial intelligence, there has been a surge of research in the last few years into the use of chatbots for educational purposes, including for language learning purposes. In this context, teachers’ attitudes and experiences have been captured in the literature (for example, Chuah & Kabilan, 2021) as well as those of students (for example, Wiboolyasarin et al., 2024), and the presence of systematic reviews of the same indicates that this field of research has reached a certain level of maturity (Huang et al., 2022, and in the context of synchronous computer-mediated communication, Sauro, 2011). In these cases, the use of chatbots and chatrooms has generally been to provide extra support to learners or to allow them flexibility in their learning modes, timings and personal engagement preferences without the online presence of a human teacher. These are all useful endeavours but do not reflect the nature of our intentions in conducting the present activities and reporting on our experiences. Our purpose was to provide student teachers with opportunities to practise teaching in chatroom mode, where humans are interacting with each other in order to support language learners. This mode of teaching is one among others that our student teachers get the opportunity to try during their MA so that they have as wide a range of experiences as possible when graduating from the programme. Indeed, the few studies that we identified of human-to-human communication in language learning chatrooms seem to be from some years ago. We review them briefly below as background to the current study.

In 2011, Hamano-Bunce reported on a study comparing chatroom and face-to-face oral interaction for language learning in the United Arab Emirates higher education context. He found that, despite some advantages, chatroom interaction was less effective than face-to-face oral interaction because slow typing considerably hampered language learning. He concludes that the chatroom mode may be best used outside of the classroom rather than within. Taking comparisons to a different level, other studies compare synchronous and asynchronous online communication (see papers in O’Rourke & Stickler, 2017, special issue on various types of online communication) and conclude that although both modes have advantages and disadvantages, ‘the most salient properties of synchronous computer-mediated communication (SCMC) are real-time pressure to communicate and a greater degree of social presence relative to asynchronous communication’ (O’Rourke & Stickler, 2017, p. 1). At the same time, Su and Garcia (2008, p. 947) suggested some time ago that ‘since most students are now using chat rooms, teachers must develop a better understanding of how to best utilize these systems in language teaching’. This highlights the importance of such a pedagogic skill, even if its realisation may have changed since that time. In a teacher education context, all such developments and skills are important so that student teachers get the opportunity to experience them first hand and critically assess their benefits, even if they ultimately decide that may not be beneficial or practical.

Based on this review, the existing studies with human interactions in chatrooms differ from ours in that they report the experiences of qualified and practising teachers and/or the quality of the interactions and tasks on the part of the learners. From what we can tell, our work is unique in reporting a study related to practising teachers using a chatroom corpus to scaffold their first experiences of teaching synchronously in written-only mode chatrooms and recounting their experiences as a reflective practice and professional development endeavour for English language learning purposes.

2.3. The Teacher-Student Chatroom Corpus

The Teacher-Student Chatroom Corpus (TSCC; Caines et al., 2020, 2022) was collected as a means to observe how language teachers manage and deliver a one-to-one English lesson in an online chatroom environment. The pedagogic advantages of this setting are that the dialogue could be relatively informal, focused on one individual and their learning needs, and conveniently take place online without the need for classroom facilities or in-person contact. This last advantage proved to be highly relevant during the lockdowns imposed in many countries due to the COVID-19 pandemic which spread globally in 2020.

The chatroom used (from which the TSCC was collected) was a basic web application, as shown in the screenshot in Figure 1. There was no facility to insert images (including emojis), though teachers were encouraged to insert links to external multimedia (e.g., online videos, images, teaching materials). In total, the Corpus contains 260 one-to-one lessons between two teachers and 13 different students, amounting to 41,484 conversational turns and 362,440 words. The CEFR level of the learners was judged by annotators with teaching experience to range from B1 to C2, and the chatroom conversations have been annotated with discourse or pedagogical features such as topic development, elicitation, scaffolding and enquiries (see Caines et al., 2020, for details). A subset of the data has been annotated with adapted labels from the Self-Evaluation of Teacher Talk framework, such as ‘confirmation check,’ ‘form-focused feedback’, and ‘seeking clarification’ (SETT; Walsh, 2006).

Figure 1.

Screenshot of the chatroom used in this study.

Participants in the chatroom lessons gave their informed consent for the transcripts to be included in a corpus which would be released for research purposes (Available by request via https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSfu9IkTLWw97cy8YPrKlhHijBOEYuKjJNiTpVX1UgASbha1AQ/viewform, accessed on 11 September 2025). For the purposes of the study reported in the present paper, we randomly selected three chatroom transcripts from the Corpus as examples for the MA TESOL students to review and prepare with, as described in more detail in the next section.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Context

The participants in this study were 15 students enrolled on a one-year MA in TESOL in Ireland, eight were Irish and seven were international, with ranges of experience from none to 5 years. The programme comprises two taught semesters (12 weeks teaching in each) and a final semester devoted to either a research project or a work placement. These students take three core modules on language, pedagogy and applied linguistics research in each of the taught semesters of their programme, and they can also choose one from a number of optional modules, including teaching practice, academic literacies, blended learning, and professional discourse. The current paper focuses on the Teaching Practice module, which runs in both semesters, although our focus here is the second semester of the programme. During this module, they teach the international/ERASMUS students taking EFL classes at the university. Before the actual practice begins on this module, students receive six weeks of practical input and scaffolding that aligns with content from their core modules, while also preparing them to teach our EFL students. This scaffolding includes peer teaching and feedback, watching short teaching episodes on, for example, building rapport with learners, creating context in a lesson and grammar teaching, and collaboratively reflecting on them, and also talking about practical skills and strategies from their core modules and how they could be implemented in a classroom setting (such as elicitation and questioning). They then spend the last six weeks of the semester teaching, both online and face-to-face, being observed, getting supervisory feedback and reflecting, through structured tasks, on these lessons and the process more generally. The teacher educator involved in the delivery of this module is one of the researchers and authors of the present paper.

As seen in Table 1, in year 1 (2023), we had seven student teachers paired with 7 EFL students for one-to-one teaching sessions, however recruitment of EFL students proved more difficult in the second year, and therefore in 2024 we had 8 student teachers paired with 4 EFL students, thus consisting of two student teachers and one EFL student per group. In this case, one student teacher led the first chatroom teaching session, and the other student teacher led the second chatroom teaching session.

Table 1.

Participation in the Chat Project.

3.2. The Chatroom Teaching Project

In the Spring semesters of 2023 and 2024, we ran the chatroom teaching project, which was integrated into the teaching practice module and was used in addition to the regular online and face-to-face teaching opportunities with which the student teachers engage. The chat project ran from weeks 3–9 of the semester, details of which can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Structure of the Chatroom Teaching Project.

As shown, in Week 3, students focussed on classroom discourse and the features of teacher talk, in particular Walsh’s (2006, 2011) SETT framework, as a means of scaffolding how they might describe and analyse their own talk over the following weeks. In Week 4, the student teachers reviewed three samples of chat teaching sessions from the existing TSCC corpus (Caines et al., 2022). The reasons for this were two-fold: firstly, we wanted to show and encourage them to reflect on the features of chatroom teaching, and secondly, they were able to use these transcripts as inspiration for their own future teaching tasks/activities using the same tool. Students were then asked to email the teacher educator the tasks that they planned to use for the following week’s teaching. In Week 6, the student teachers were paired up with EFL students at the University for additional one-to-one or one-to-two teaching sessions. They had 30–40 min for this teaching session, and normally one to two tasks were completed during this time. The following week (Week 7), the student teachers reviewed their own chatroom transcripts to analyse any features of their personal chatroom classroom interactions they chose to (examples include levels of formality, providing clarifications, checking understanding), and they reflected on this together with the teacher educator, as well as gathering feedback from the other student teachers in the group. These practices are in line with many guidelines and frameworks for reflective practice (T. S. Farrell, 2024; Mann & Walsh, 2017). In Week 8, the process was repeated, where the student teachers were paired with the same EFL students for another chatroom teaching session of 30–40 min with new tasks. Finally, in Week 9, the student teachers reviewed their own transcripts, gave feedback to the teacher educator/researcher, and reflected on the process. These reflective sessions were online and recorded by the teacher educator for later analysis.

3.3. The Data

3.3.1. The Reflections Corpus

During the two stages of feedback and reflection (weeks 7 and 9), we audio-recorded data from the student teacher–teacher educator interactions, creating what we call the Reflections Corpus. These two feedback discussions (Reflections Corpus) lasted 33 min in total (see Table 3). Students were given their transcripts after their sessions so they could look through them and reflect before the discussion with the teacher educator. In total, there were four sessions, two sessions for the 2023 group and two for the 2024 group (a reflective discussion one week after each chat session each year), and for the purposes of this paper, we focus on two of those four sessions (one from each year). Students granted permission for these to be recorded on MS Teams, and in line with ethical approval from the University and associated protocols, all data has been anonymised.

Table 3.

Data sources for the chatroom project.

During these feedback sessions (in weeks 7 and 9), the student teachers were asked a number of questions designed to gauge their experiences of the chatroom teaching sessions, and what they noticed about the use of language, with the broad aim of encouraging them to reflect on the experience, while also encouraging reflective practice (T. S. C. Farrell, 2019). For example, for both years of data collection, the teacher educator asked the following questions:

- What are your reactions to teaching in the chat room?

- How does this experience compare to your last experience of the chatroom?

- Did you notice anything else about your use of language when using this tool?

- Did you notice anything else about your student’s use of language when using this tool?

- What, if anything, might you do differently if you were to use this tool again? Why?

- Any other comments?

3.3.2. The Limerick Teacher Student Chatroom Corpus (Limerick TSCC)

The analysis of the written chatroom interactions between the student teachers and the EFL students (Limerick TSCC) form the basis for the quantitative, corpus-assisted analysis for the present paper, totalling approximately 16,000 words from 22 chatroom lessons. A summary of both data sources is presented in Table 3.

In the following sections, we firstly integrate the analysis of both datasets to illustrate the (largely aligned) themes that emerged from the quantitative and qualitative analyses. The Reflections corpus data from 2023 and 2024 are used for the qualitative data, however the Limerick TSCC data analysed for this present paper is based on the 2023 group as this has been analysed to date (focussing on 9253 words from 14 lessons). We then move to a more qualitative review of the Reflections Corpus to examine it through the lens of the desirable components of reflective practice as articulated in Farr and Farrell (2025).

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Phase 1: Reflections Corpus and Limerick TSCC Corpus Analysis

The first part of the data analysis aimed to answer the first research question posed at the outset of this paper, that is, what are student teacher experiences of teaching in written synchronous chatroom mode as evidenced in both their shared reflective discussions and through a corpus-based analysis of the chatroom transcripts? To do this, we performed a quasi-thematic analysis of the Reflections Corpus and also some linguistic analysis of the Limerick TSCC (including formal language use, teacher talking time and turns, feedback, clarity and understanding, task design, and development over time). We present the results under the highlighted themes in this section.

A quasi-thematic analysis (themes partially determined by the questions asked) of the Reflections Corpus revealed the themes listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Themes identified in the Reflections Corpus.

4.1.1. Theme 1: Formal Language Use

In 2023, after the first chatroom teaching session, some of the student teachers noted that their language seemed more formal than what they perceived they would use in a face-to-face classroom, which, while consistent with data in other studies (Knight et al., 2013), somewhat surprised them. Having said that, both the 2023 and the 2024 groups believed that their language became more informal over time, suggesting growing levels of comfort and ease with the written mode. Both groups also felt their students’ use of language was more informal than in the face-to-face classroom but not as informal as they would be when in contact with friends, for example, thus suggesting a rolling scale of formality in chatroom teaching contexts. Consider the following extract from the Limerick TSCC, when the student teacher sets a tone of informality with their opening enquiry, “How is it going today?”

- Student: Great! Im on my way to Galway

- Teacher: Oh, do you have plans in Galway?

- S: I’m going to the boardgame cafe with a friend, but other than that we don’t really know any fun things to do there. Any recommendations?

- T: oh that sounds nice! I’ve only been there there couple of times myself. The aquarium was a personal favourite of mine:)

- S: Omg that sounds amazing! We’ll look into it

- T: have fun! Galway is a lovely city even to just walk around anyway

- S: Thank you! It is

- T: so what I wanted to do today is to look into some idiomatic language. How does that sound?

- S: Sounds interesting

On the student side we can observe several informal features: a lack of standard punctuation and orthography (“Im” for ‘I’m’, sometimes lacking turn-ending punctuation marks and opening capitalisation both by student and teacher), use of emoticons and emoji, acronyms (“Omg” for ‘oh my god’), and ellipsis of subjects and verbs (“Any recommendations?”, “Sounds interesting”). The student teacher responds with similar levels of informality to the student, befitting the chatroom context, and even with the switch to pedagogical focus, the student teacher starts with the discourse adverbial so to start their turn (“so what I wanted to do today…”), a token which is often used in spoken, informal contexts to change topic (Biber et al., 1999; Carter & McCarthy, 2006; Carter et al., 2011). The post discussions the student teachers had with the educator thus gave them the space to reflect on their use of language. Much like the work of Walsh (2006, 2011) using his SETT framework as a reflective tool in LTE, the student teachers in this study could use the corpus transcripts as data and evidence for reflective deliberations.

4.1.2. Theme 2: Teacher Talking Time (And Turns)

The student teachers in both years also noted a high level of teacher talk, with one student teacher calculating her turn-taking split with her student to be 61 versus 35 turns, meaning her turns almost doubled those of her student. This is indeed typical of one-to-one teacher/mentor and student interactions such as post-observation feedback sessions between a teacher educator and a student teacher (Vásquez & Reppen, 2007), and therefore is not that surprising as the teacher needs to manage, scaffold and direct the interaction.

The Limerick TSCC analysis shows that indeed the student teachers took the lead in the chatroom lessons, contributing the majority of turns (with 56% of the 1050 total turns in the 2023 chat transcripts) and to a greater extent the majority of words (with 66% of the 9253 words in the 2023 chat transcripts). Therefore, student teacher turns were longer than the students’, at an average of 10.4 words per turn by the teachers as opposed to the 6.8 words per turn by the students.

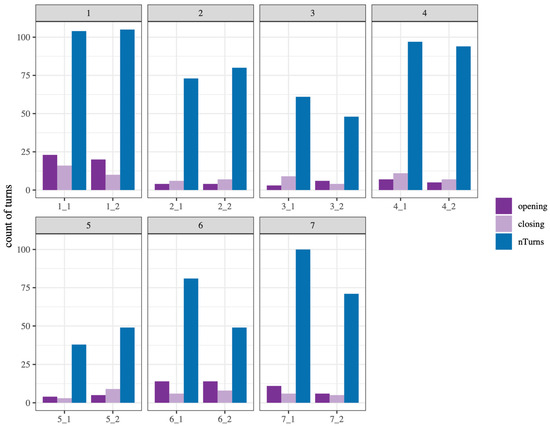

On the other hand, the student teachers kept the opening and closing phases of the lessons as brief as possible, moving to exercises and the main part of the lessons quickly (opening and closing phases were determined through human annotation: the annotation guideline was to indicate an opening sequence from the beginning of the lesson to the first change of topic; closing sequences were identified at the point where the teacher began to wrap up the lesson). Figure 2 shows how few opening or closing turns there were (in purple) in each lesson for each individual student teacher in 2023. This efficiency with time management meant that there were dozens of turns within each lesson for the purpose of core teaching and learning.

Figure 2.

The number of chat turns spent on opening or closing the lessons compared to the total number of turns in the lesson, with a facet for each student teacher in the 2023 cohort, and their first and second lessons differentiated on the x-axis.

The student teachers also noticeably paced the lessons carefully, not chatting in lengthy turns or complex ways, but taking the time to set the focus for the lesson clearly and check that they had ‘buy-in’ from the student for the lesson plan. Pedagogical topics tended to be specific and meaning-focused: for instance, focusing on the appropriate usage of idioms and collocations, phrasal verbs and prepositions, verb inversion, and gerunds.

The chat turns have a typical chatroom structure involving multiple consecutive turns by one participant before the other one responds, and resulting cross-threading of turns in a non-sequential fashion. Indeed, 33.4% of the turns are part of multiple turns in succession by the same participant, as opposed to single turns by one participant at a time. For instance, multiple turns and cross-threading are both found in the following exchange:

- T: That’s lovely! [topic a]

- S: I’m sorry that I really bad at typing. [topic b]

- T: Is it your first time in Ireland? [a]

- S: yes [a]

- S: last semester I was in UK for exchange [a]

- T: Don’t worry, I’m bad at typing too! [b]

- T: That’s great!! Where did you go in the UK? [a]

It can be seen that conversation topic [a] and topic [b] are interwoven during these few turns, with the student teacher picking up on the ‘bad at typing’ comment by the student (topic [b]) before resuming the ongoing conversation about topic [a]. Features of conversation (such as turn-taking, opening and closing sequences, etc.) is not something that is readily available for student teachers to analyse, unless they have data like the corpus data presented here. Much of what happens in a classroom can go unnoticed by a student teacher, who is trying their best to deliver a lesson, and therefore not reflecting in action (Schön, 1983), on their use of language. The CBRP approach we used, thus allowed them to reflect on action (Schön, 1983) and this provided them with additional input to align with their thoughts, which in turn can deepen their understanding of the minute aspects of interaction and engagement. This understanding and awareness is a necessary step to the development of their practice (T. S. C. Farrell, 2016).

4.1.3. Theme 3: Positive Feedback, Clarity and Understanding

The student teachers in 2023 agreed that there was more variety in their use of language, with particular reference to their use of positive feedback, and studies on type-token ratio (TTR) and lexical density in spoken, written and online modes would indeed support this as they show that online and written modes promote/produce a higher TTR, thus using more distinct words relevant to total words when compared to speech; it is therefore not surprising that the student teachers use more variety in their use of language when giving feedback as they have time to think about language use (Clavel-Arroitia & Pennock-Speck, 2021).

The fact that the chatroom was purely textual also resulted in the student teachers needing to use a variety of understanding checks, as this mode does not allow visual or paralinguistic features often employed to enhance understanding (Darics, 2013), and they are therefore reliant on their use of language alone, which they appreciated. Along similar lines, their instructions needed to be extremely clear and often had to be modified for the learners. This was felt to be an extremely useful learning experience for both groups of student teachers, who often struggle with using clear instructional language in the classroom (A. Farrell, 2015). The student teachers in both groups also agreed that the instructions had to be clearer than in spoken teaching contexts, and they reported that when they noticed issues in their discourse, they could modify this as it was a written mode, similar to other studies which show that online chatting encourages noticing (Lai & Zhao, 2006).

Data from the Limerick TSCC showed that a well-used format was to transform given sentences into another form:

- T: Try to invert the adverb, verb and subject in the following.

- T: She had never tried so hard before

- S: never had she tried so hard before

Other student teachers would elicit explanations to check for understanding of grammatical items, or ask for examples of a construction in use. Sometimes, as was welcomed and evidenced in previous lessons from the TSCC, the student teachers would link to external resources for teaching purposes—such as the YouTube video in the following example:

- T: Now for our final task, I’m going to ask you to watch this video

- T: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tcgZJ8uoAtY (accessed on 3 March 2023)

When the student teachers made mistakes, they might also self-correct as in the following example:

- T: One last little task: coud you write a sentence using of the idioms we have seen today?

- T: *one of the idioms

Around half of all the sequence types in the conversations in the Limerick TSCC involving the 2023 student teacher cohort are enquiry, presentation, or exercise sequences (discourse sequences were determined through human annotation, annotation guidelines, annotator training and feedback). This means that the student teacher was checking the student’s knowledge or understanding, or presenting some teaching points to the student, or setting tasks for them to respond to. Other common sequence types were lesson openings, closings and admin, reference to resources, redirection of the discourse or scaffolding to support exercises and learning. This distribution of sequence types is consistent with that seen in the previous chatroom lessons collected in the TSCC, and indicative of the learning-from-examples opportunity (namely, reflecting using evidence) that the student teachers had in this programme, as well as their development towards skilled users of the one-to-one chatroom teaching environment. Classroom management is a difficult and wide-ranging field and can be particularly difficult for student teachers (A. Farrell, 2015), and allowing them to reflect on areas such as feedback and giving instructions using data from their own interactions with students is invaluable. In fact, data-led reflective practice has been advocated for by many (Walsh & Mann, 2015; Sert & Jonsson, 2024), as it can aid understanding, deepen reflections and promote professional development.

4.1.4. Theme 4: Task Design

Task design was another area that was explicitly discussed at the initial stages of the project, in class, with the teacher educator and the student teachers, and at this point, both groups of student teachers agreed that the space was more conducive to lexical tasks than grammatical ones, and that timing was an issue to be considered, namely that fewer tasks would be completed in a chatroom mode (see also Hamano-Bunce, 2011; Qiu et al., 2024). This is because lags in turn taking due to typing prevented them from giving lengthy explanations, often required for grammatical issues, which is important to consider for task design (Hamano-Bunce, 2011).

The Limerick TSCC data showed that the student teachers set exercises which were well-suited to the chatroom environment. These could be gap-fillers such as the following:

- T: Can you fill in the blank using the superlative of the adjective big—The Pacific Ocean is the ___ ocean in the world.

Towards the end of the first lesson, the student teachers set expectations for the next one, in a similar way to existing lessons already collected in the TSCC, which were taught by more experienced teachers.

- T: If you had to have another chatroom session with me, what would you like to see or study?

The use of appropriate tasks can promote interactional competence, where tasks can be shaped to promote meaningful communication (Sert & Jonsson, 2024), and this is precisely what the CBRP process did for the student teachers in this study. Allowing them time and space to consider and reflect upon tasks that would be appropriate for the chatroom context in particular resulted in tasks designed to maximise the interaction between the learner and teacher. This type of reflection can also support professional identity formation, where the student teachers can see themselves as designers, and not just deliverers of material (see for example, Mishan & Timmis, 2015).

4.1.5. Theme 5: Development over Time

After the second chatroom task, the 2024 group noted that their language became more informal over time, and this was potentially because they were more relaxed, which is similar to the comments the 2023 group made about their students’ use of language. The student teachers also felt more at ease using the chatroom in particular as they had used it before and had interacted with the same students before. Due to fewer students taking part in 2024, these student teachers worked in pairs, which could also have helped reduce levels of anxiety and unease with the tool (the EFL students were not aware they had two teachers), and indeed research has also shown that online chatting promotes positive social presence (O’Rourke & Stickler, 2017). This further resonates with collaborative learning and peer scaffolding (Vygotsky, 1978) and should be borne in mind for future iterations of the project. This group also noted evidence of small talk in their chatroom interactions. Studies highlight the importance of small talk in professional settings (Koester, 2012; Pluszczyk, 2020), and indeed research shows that small talk performs a discursive strategy resulting in enriching online classrooms (Chui et al., 2021). The student teachers noted a clear reduction in small talk in lesson two compared to their first session with the students, as they were potentially more comfortable getting quickly to the task at hand, and assuming more of a teacher role in this space. It could also be that they felt small talk was not needed at this point in their interactions and they found other ways to demonstrate social presence such as the use of emojis and the informal language as discussed earlier (Kwon et al., 2021).

In addition, they adopted the relatively informal style typical of teacher turns in the TSCC, featuring non-standard orthography, punctuation and emojis, as well as the occasional typo or non-grammaticality.

- T: That’s why we’re doing this chatroom session today:)

- T: The UK and now Ireland, you will have soon visited all the British isles haha

- T: That’s great!! Where did you go in the UK?

The chatroom transcripts in the Limerick TSCC show how the student teachers put their plans into practice regarding lesson structure and setting exercises for the learner. The student teachers were given the opportunity to read some sample transcripts from the TSCC and to reflect on how this would affect their own teaching practices (as described in the Methodology section earlier). They therefore had the chance to pre-formulate some plans and techniques for teaching one-to-one in online chatrooms and this is evidenced in the transcripts from their own lessons. This data-led approach to RP resulted in rich discussions between the student teachers and the teacher educator as the corpus data provided evidence to support their initial reflections, which in turn gave them more confidence in their thought process. It also suggests that they are feeling more comfortable in this environment and probably progressing nicely from being more peripheral members of this community, to more legitimate and full members, to use Lave and Wenger’s terminology (Lave & Wenger, 1991), also an indication of an evolving teacher identity (Barkhuizen, 2021). This is a prime example of what Dewey (1933) would call, learning from experience.

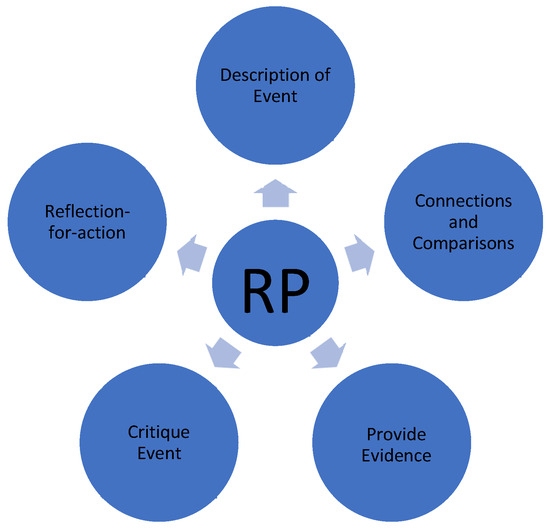

4.2. Phase 2: Reflective Practice Engagement

In line with the articulated and implemented goals around the promotion of RP on the teacher education programme, and relatedly in order to answer the second research question (what is the nature of the reflective discussions with reference to Farr and Farrell’s (2025) evaluation criteria for reflective practice engagement: description, connections and comparisons, evidence, critique, reflection for action?), we analysed the reflective language in the Reflections Corpus. To do this, we drew on Farr and Farrell’s (2025) five components of reflection, which they believe are important and often the focus of assessment of written reflections on teacher education programmes. These include, in no particular order, a description of an event, something which is based on narrative, is factual and objective. The second component is making connections and comparisons, possibly from the literature, observed practices, feedback from students, for example, and the third component is providing evidence, often in the form of recordings, feedback, and personal accounts, whereby the student teachers can use evidence to deepen and inform their understanding. The fourth component is a critique of the event or the topic of discussion, where there is some evaluation and reflection performed as a means of further understanding the issue, and the fifth and final component is reflection for action, where a proposed change is identified, limitations are accepted or there is evidence of new/reformed learning (see Figure 3). We therefore used the Reflections Corpus to qualitatively explore the dialogue for these components in order to evaluate the nature of the reflective engagements.

Figure 3.

Important components in the assessment of reflective practice assignments (Farr & Farrell, 2025).

From a qualitative discourse level analysis of the transcripts, we find the core components mentioned above in the interactions with the teacher educator, and indeed scaffolded by the teacher educator, and thus evidence of the reflective cycle emerging in the data. A relevant example including most of the components can be seen in the following extract on the topic of small talk.

ST = Student teacher

TE = Teacher Educator

- ST: Well, my situation was a bit different from the one we had the last time because last the last time ST2 was typing and the second time I presume she didn’t know that there was another person, obviously.

- TE: Mmhm

- ST: So she thought that she was still talking to ST2. I I I decided not to tell her that I’m some that I’m the other person like so I just kept going. [description]

- TE: Ok

- ST: And the second time, the first time, she was really eager to talk, she asked I think everything about the the MA TESOL program [evidence]. Yeah, she was chatting away with ST2 and it was very difficult to kind of move into the class direction into what we had prepared. So that was a bit difficult [critique], but the second time it happened almost straight away. Maybe a few entries about like plans and the weekend and then I just said, well, OK, yeah, almost straight into it

- TE: That’s interesting. You know, in the chat remember we read them, we read a few examples at the beginning and we were looking and we said it took them about 20 min of small talk to get into the lesson. So I wondered, is that kind of those initial lessons maybe need more small talk and you can get straight into it from from then on? [evidence]

- ST: Yeah, I presume so we yeah.

[Discussion moves to talking about how ST challenged this student, who was very strong]

- ST: Yeah, I think I had seven or eight idioms and half of them she got correct half of them she got wrong. So there was a bit of i + 1 [connections and comparisons] so she did learn something which I was glad about [evidence and critique]

Extract 1: Evidence of RP Components

Here, the student teacher begins with a description of the event, where there was confusion on the part of the learner about which student teacher they were interacting with, and the student teacher did not clarify that there had been a change. In the first chat session, the student in question seemed eager to engage in small talk, and the student teacher provides evidence for this statement by stating that the student enquired about the MA programme the student teacher was engaged in, and he provided a critique in the realisation that this engagement in small talk was difficult to move away from in order to progress to the task at hand. He then goes on to state that in the second chat session, this was not the case, and that the small talk had dramatically reduced, again providing evidence of this (a few entries). We also see the teacher educator coming in here and scaffolding, by providing further evidence of the previous example chat sessions they had examined as a group, and hinting that this is a feature of online chat lessons carrying important pragmatic functions.

Indeed, the affordances of scaffolding and social learning (Farr et al., 2019; Vygotsky, 1978) that group interactions and those with an expert-other can provide for deepening reflections is well-cited in the literature (Mann & Walsh, 2013; Sert, 2019). The discussion then moves on to a focus on how the student teacher challenged the student, and there is evidence of him making connections and comparisons in his reference of Krashen’s (1982) i + 1 theory and his understanding of the discourse/answers from the student in the chatroom. He finishes his turn with evidence (the student learned) and a critique (I was glad). From this short extract, we can see evidence of the student teacher moving through the components of reflection and shaping his understanding of a situation, using knowledge, experience, and evidence of what was happening to support this. The teacher educator also plays an important role in this reflective cycle. What is not found in this extract was the final component, reflection for action. This is not to say that it is not present in the data, and from trawling through it, the following extract was identified as a relevant example of reflection for action. This relates to an interaction about the chatroom being more suitable for lexical tasks than grammatical ones.

ST = Student teacher

TE = Teacher Educator

- ST1: Sorry, we were at this conference yesterday where there was a lot of talk about like pronunciation and ah integrating pronunciation and grammar and vocabulary. [description]

- TE: Ohh, [guest lecturer]

- ST1: Yeah, yeah, I I and I suppose, like just what struck me after that and is well, you really mightn’t want to be introducing new vocabulary to this method if it’s like his big thing was you should hear the words before you see it written because of the you can be led astray by the by the written word the such you know. [connections and comparisons]

- TE: That’s a really good point.

- ST1: So yeah, so like it’s it’s just another another factor. Now I think that’s I wouldn’t have thought of until listening to that lecture yesterday, you know. [connections and comparisons]

- TE: Mmhm

- ST2: So you might want to refer them to dictionary to check the pronunciation after the session. [reflection for action—collaborative]

Extract 2: Evidence of reflection for action

The student teacher begins with a description of an event about a student conference held at the University, and he makes connections and comparisons between the content of the guest lecture he attended and the task to be used in the chat session. This is precisely what we want student teachers to do, namely align the theory with their practice, or at least think of the practice in terms of the theory (Cirocki & Widodo, 2019; Cirocki et al., 2019) and vice versa. This also resonates with the work of Wallace (1991), who believes that RP can be used to bridge the gap between professional knowledge (received knowledge) and classroom practice (experiential knowledge). The interesting part of this interaction is that a second student teacher engages with reflection for action by suggesting a strategy for the future regarding issues around pronunciation and the lack of audio in the chat session. The second student teacher is clearly helping to solve a problem, and this example thus demonstrates the power of collaborative reflective practice (Mann & Walsh, 2013) and the power of social learning, where deeper levels of reflection (e.g., reflection for action) can be achieved with the help of a peer or an expert other (Vygotsky, 1978). From the analysis of the transcripts, we believe there is evidence of reflective discourse, although more work on reflection for action would be required. This point was also raised by the students in the reflective discussions with the teacher educator who, they believed, played a role in scaffolding them to rationalise and evaluate in order to make sense of their reflections on their experiences. However, from examining the interactions with these groups, it was found that she did not push forward reflecting (T. S. C. Farrell, 2018) as much as she would do in one-to-one TP feedback sessions for example, possibly for face-saving reasons when with groups of students. Although reflection for action was envisioned for these groups, the discussion with the teacher educator did not focus on this phase of the reflective cycle as much as the retrospective aspects of reflection, and therefore a third chatroom session might help to close this loop (Argyris, 1977). We therefore reinforce the importance of social and collaborative learning for reflective practice, which has, for a long time, been advocated for.

5. Conclusions

Through a combined qualitative and quantitative analysis of the Reflections Corpus and the Limerick TSCC, we found many alignments between the student teachers’ perceptions of their chatroom teaching (their espoused beliefs), and the evidence presented from the analysis of their chatroom data. This is especially reassuring and could suggest the positive impact of the CBRP they engaged in with the general TSCC in advance of their own teaching. In other words, the insights and skills learned from the prior CBRP not only informed their teaching but also their ability to accurately interpret what had happened in this teaching, an invaluable and desirable attribute for continuous professional development as they approach the end of their formal teacher education programme. This was evidenced across the various themes presented in the previous section. For example, there was clear evidence of learning from the first phase of the CBRP (i.e., analysing sample lessons from the TSCC), stemming from the fact that the student teachers used the chatroom appropriately, such as managing the online interactions with ease and control, and the patterns, sequence types and task format that the student teachers used resembling the interactions they had previously analysed and discussed. The combined analysis also highlighted an accurate perception of the turn-taking split, which, while high on the part of the student teachers, was found to be pedagogically focussed, with much evidence of language being used to clarify, check understanding and provide positive feedback, all essential remits of teacher talk. Indeed, the student teachers noted in the Reflections Corpus that they were aware that they were taking more control of the discussion space in the chatroom; however, the corpus findings demonstrate that these turns were pedagogic in form and scaffolded and evaluated the learners. This finding might make the student teachers view this turn taking split in a different, and indeed more positive, light, as a requirement that this is necessary in this online environment. This is also somewhat in line with the student teachers’ comments about the reduction in small talk (often as opening turns) in the data. The lack of small talk in the sessions is another example of how focussed and task driven the chat sessions were. The CBRP approach we used therefore can assist student teachers in uncovering tacit knowledge (Schön, 1983), which is often difficult to articulate. The corpus evidence is key here and can be used not only for individual reflective practice but also for the co-construction of knowledge.

As well as turn-taking being dominated by the student teachers, the corpus analysis also revealed that the turn lengths were longer for the student teachers, and this could be connected to their opinions on their use of language, their need for clear instructions in this non-visual mode and the capacity to modify their discourse if necessary, which could all result in more lengthy directions, and responses from the student teachers. We were indeed somewhat surprised that the student teachers did not articulate more irritation at having to field lengthy written explanations, which take time and written space (see, for example, Hamano-Bunce, 2011). It may be that if this chatroom teaching extended over a longer period, such frustrations may have been more apparent. The corpus data also shows that the student teachers designed tasks that were appropriate for the mode, and the use of meaning-related, gap-fill, sentence transformations and external links were used with skill by the student teachers—once again the impact of the first phase of the cycle here is evident, where the student teachers viewed sample chatroom teaching sessions from the corpus and gained inspiration from them. Issues around informality that emerged from the student teachers’ perceptions are also supported by the data in the corpus such as evidence of non-standard orthography, punctuation and emojis, as well as the occasional typo or non-grammaticality.

From the analysis, we are reassured by the findings that the student teachers are moving through the stages and components of the reflective process, using the two TSCC corpora as supporting evidence. Perhaps the next step here, consistent with Farr and Leńko-Szymańska’s (2023) corpus-based reflective practice, would be to encourage the student teachers to use their transcripts as searchable corpora in more quantitative ways to garner further insights into their use of language, and in turn further their development. This may be possible in future iterations as the corpus grows overall and for individual teachers. Also notable is the fact that the teacher educator plays a role scaffolding and extending the boundaries of reflections, as was seen in particular in the Reflections Corpus. It may be that a third chatroom teaching session where student teachers’ plans could be put into action, and a reflective follow up with the teacher educator and peers could potentially result in enhanced reflection for action discussions. Based on the findings, we believe that the chatroom teaching space enables new forms of teaching and skills training in a low-pressure environment and is thus a valuable form of teaching practice approximations. Furthermore, CBRP can support student teachers undertaking chatroom teaching practices. Our findings also suggest that CBRP can be a valuable tool for promoting evidence-based deeper learning and professional development.

Author Contributions

Introduction and Literature Review, F.F.; Methodology A.C., E.R. and P.B.; Analysis E.R., A.C. and F.F.; Conclusions F.F. and E.R.; Reviewing and Editing E.R., F.F., A.C., P.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The third and fourth authors are supported by Cambridge University Press & Assessment.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Limerick (protocol code 2021-03-13-AHSS and date of approval 2 March 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adnan, M., Tondeur, J., Scherer, R., & Siddiq, F. (2024). Profiling teacher educators: Ready to prepare the next generation for educational technology use? Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 33(4), 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C. (1977). Double loop learning in organizations. Harvard Business Review, 55(5), 115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Barkhuizen, G. (2021). Language teacher educator identity. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Biber, D., Johannson, S., Leech, G., Conrad, S., & Finnegan, E. (1999). Longman grammar of spoken and written english. Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Brickhouse, T. C., & Smith, N. D. (2000). The philosophy of socrates. Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, B. M., & Cuenca, A. (2012). Conceptualizing the roles of mentor teachers during student teaching. Action in Teacher Education, 34(4), 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caines, A., Yannakoudakis, H., Edmondson, H., Allen, H., Pérez-Paredes, P., Byrne, B., & Buttery, P. (2020, November 25). The teacher-student chatroom corpus. Proceedings of the 9th Workshop on NLP for Computer Assisted Language Learning (pp. 10–20), Gothenburg, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- Caines, A., Yannakoudakis, H., Edmondson, H., Allen, H., Pérez-Paredes, P., Byrne, B., & Buttery, P. (2022, December 9). The teacher-student chatroom corpus version 2: More lessons, new annotation, automatic detection of sequence shifts. 11th Workshop on NLP for Computer Assisted Language Learning (pp. 23–35), Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, R., & McCarthy, M. (2006). Cambridge grammar of english. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, R., McCarthy, M., Mark, G., & O’Keeffe, A. (2011). English grammar today. The A-Z of spoken and written grammar. CUP. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y., Jensen, S., Albert, L. J., Gupta, S., & Lee, T. (2023). Artificial intelligence (AI) student assistants in the classroom: Designing chatbots to support student success. Information Systems Frontiers, 25(1), 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, K.-M., & Kabilan, M. (2021). Teachers’ views on the use of chatbots to support English language teaching in a mobile environment. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 16(20), 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chui, M. H. L., Mak, B. C. N., & Cheng, G. (2021). Exploring the potential, features, and functions of small talk in digital distance teaching on Zoom: A mixed-method study by quasi-experiment and Conversation Analysis. In W. Jia, Y. Tang, R. S. T. Lee, M. Herzog, H. Zhang, T. Hao, & T. Wang (Eds.), Emerging technologies for education (vol. 13089). SETE 2021. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirocki, A., Madyarov, I., & Baecher, L. (2019). Contemporary perspectives on student teacher learning and the TESOL practicum. In A. Cirocki, I. Madyarov, & L. Baecher (Eds.), Current perspectives on the TESOL practicum. Educational linguistics (Vol. 40). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirocki, A., & Widodo, H. P. (2019). Reflective practice in English language teaching in Indonesia: Shared practices from two teacher educators. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research, 7(3), 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Clavel-Arroitia, B., & Pennock-Speck, B. (2021). Analysing lexical density, diversity, and sophistication in written and spoken telecollaborative exchanges. Computer-Assisted Language Learning Electronic Journal, 22(3), 230–250. [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee, D., Fox, A., Hearst, M. A., & Hartmann, B. (2014, March 4–5). Chatrooms in MOOCs: All talk and no action. First ACM Conference on Learning@ Scale Conference (pp. 127–136), Atlanta, GA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Darics, E. (2013). Non-verbal signalling in digital discourse: The case of letter repetition. Discourse, Context & Media, 2(3), 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. (1904). The relation of theory to practice in education. Teachers College Record, 5(6), 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process (revised ed.). D.C. Heath. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, F. (2022). How can corpora be used in teacher education? In A. O’Keeffe, & M. J. McCarthy (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of corpus linguistics (2nd ed., pp. 456–468). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Farr, F., & Farrell, A. (2025). Reflective assignments in TESOL and applied linguistics. In N. Bremner, & S. Mohammadi (Eds.), Completing assignments in TESOL and applied linguistics. A practical guide (pp. 188–201). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Farr, F., Farrell, A., & Riordan, E. (2019). Social interaction in language teacher education. A corpus and discourse perspective. EUP. [Google Scholar]

- Farr, F., & Karlsen, P. H. (forthcoming). Pedagogies of practice: Student teachers’ experiences and preferences. Language Teaching Research Quarterly. [Google Scholar]

- Farr, F., & Leńko-Szymańska, A. (2023). Corpora in English language teacher education: Research, integration and resources. TESOL Quarterly, 58(3), 1181–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, A. (2015). In the classroom. In F. Farr (Ed.), Practice in TESOL. EUP. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, T. S. (2024). Reflective practice for language teachers. British Council. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, T. S. C. (2016). The practice of encouraging teachers to engage in reflective practice: An appraisal of recent research contributions. Language Teaching Research, 20(2), 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, T. S. C. (2018). Reflective practice for language teachers. In J. I. Liontas (Ed.), The TESOL encyclopedia of English language teaching (1st ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, T. S. C. (2019). Reflective practice in L2 teacher education. In S. Mann, & S. Walsh (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of English language teacher education (pp. 123–135). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, P., Hammerness, K., & McDonald, M. (2009). Redefining teaching, re-imagining teacher education. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 15(2), 273–289. [Google Scholar]

- Hamano-Bunce, D. (2011). Talk or chat? Chatroom and spoken interaction in a language classroom. ELT Journal, 65(4), 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdo, M. (2022). Critical reflection: John dewey’s relational view of transformative learning. Journal of Transformative Education, 21(1), 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W., Hew, K. F., & Fryer, L. K. (2022). Chatbots for language learning—Are they really useful? A systematic review of chatbot-supported language learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 38(1), 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, D., Adolphs, S., & Carter, R. (2013). Formality in digital discourse: A study of hedging in CANELC. In J. Romero-Trillo (Ed.), Yearbook of corpus linguistics and pragmatics 2013 (Vol. 1). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koester, A. (2012). Workplace discourse. Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, S., Kim, W., Bae, C., Cho, M., Lee, S., & Dreamson, N. (2021). The identity changes in online learning and teaching: Instructors, learners, and learning management systems. International Journal of Education Technology in Higher Education, 18, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C., & Zhao, Y. (2006). Noticing and text-based chat. Language Learning & Technology, 10(3), 102–120. [Google Scholar]

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning. Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, S., & Walsh, S. (2013). RP or ‘RIP’: A critical perspective on reflective practice. Applied Linguistics Review, 4(2), 291–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, S., & Walsh, S. (2017). Reflective practice in English language teaching: Research-based principles and practices (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M., Kazemi, E., & Kavanagh, S. S. (2013). Core practices and pedagogies of Teacher Education: A call for a common language and collective activity. Journal of Teacher Education, 64(5), 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishan, F., & Timmis, I. (2015). Materials development for TESOL. EUP. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P. (2019). Considering contextual knowledge: The TPACK diagram gets an upgrade. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 35(2), 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, B., & Stickler, U. (2017). Synchronous communication technologies for language learning: Promise and challenges in research and pedagogy. Language Learning in Higher Education, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, I., Copland, F., Viana, V., Bowker, D., & Moran, E. (2018). Teaching practice in UK ELT Master’s programmes. ELT Journal, 73(2), 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluszczyk, A. (2020). Socializing at work—An investigation of small talk phenomenon in the workplace. In U. Michalik, P. Zakrajewski, I. Sznicer, & A. Stwora (Eds.), Exploring business language and culture. Second language learning and teaching. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X., Ge, H., & Cai, J. (2024). An exploratory study on second language learner engagement in different types of interactive tasks in video-chat and text-chat communication. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 62(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauro, S. (2011). SCMC for SLA: A research synthesis. CALICO Journal, 28, 369–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seralp, E., & Griffiths, C. (2025). Novice teachers and burnout. In C. Griffiths (Ed.), Teacher burnout from a complex systems perspective: Contributors, consequences, contexts and coping strategies (pp. 115–134). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Sert, O. (2019). Classroom interaction and language teacher education. In S. Walsh, & S. Mann (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of English language teacher education (pp. 216–238). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sert, O., & Jonsson, C. (2024). Digital data-led reflections on language classroom interaction. In A. Burns, & K. Dikilitaş (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of language teacher action research (pp. 108–125). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sert, O., Wulff Sahlén, E., & Schröter, T. (2025). Corpus-based reflective practice for professional development: A collaborative micro auto-ethnography. Education Sciences, 15(1), 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.-C., & Garcia, K. (2008). Chat rooms for language teaching and learning. In Handbook of research on computer mediated communication (pp. 947–968). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Tyen, G., Caines, A., & Buttery, P. (2024). LLM chatbots as a language practice tool: A user study. In 13th workshop on natural language processing for computer assisted language learning. Association for Computational Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Tyne, H. (2023). A qualitative approach to using corpora in teacher education. Second Language Teacher Education (SLTE), 2(2), 233–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez, C., & Reppen, R. (2007). Transforming practice: Changing patterns of participation in post-observation meetings. Language Awareness, 16(3), 153–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, M. J. (1991). Training foreign language teachers: A reflective approach. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, S. (2006). Investigating classroom discourse. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, S. (2011). Exploring classroom discourse. Language in action. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, S., & Mann, S. (2015). Doing reflective practice: A data-led way forward. English Language Teaching Journal, 69(4), 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiboolyasarin, W., Wiboolyasarin, K., Tiranant, P., Boonyakitanont, P., & Jinowat, N. (2024). Designing chatbots in language classrooms: An empirical investigation from user learning experience. Smart Learning Environments, 11(1), 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y. (2003). The use of chat rooms in an ESL setting. Computers and Composition, 20(2), 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).