Abstract

One of the primary challenges of any educational system is providing effective professional development (PD) for teachers, which will integrate knowledge that can be translated into practice. Moreover, the goal of PD is for teachers to implement new practices in their classrooms. The PD model examined integrated three key components: content knowledge (literacy theory), pedagogical content knowledge (research-based strategies), and practical implementation with coaching support. First, we examined teachers’ perceptions of their knowledge development resulting from PD. Second, we investigated the extent of practical implementation of the PD by teachers and its influence on their literacy self-efficacy. Data were analyzed using dependent sample t-tests and independent sample t-tests comparing change scores among 82 elementary teachers. The teachers in the study reported significantly higher literacy knowledge and self-efficacy after PD than before. Next, differences in the teachers’ degree of implementation of PD were examined based on the teachers’ self-efficacy. Teachers who implemented 5–12 lessons showed significantly greater self-efficacy improvements (Cohen’s d = 0.80) than those implementing 0–4 lessons, demonstrating a clear dose–response relationship. This finding highlights the significance of implementing PD practices in the classroom setting and the role of teachers’ self-efficacy. The results are further discussed in relation to effective PD and a proposed extension of Shulman’s curricular knowledge. Limitations include reliance on self-reported measures and a homogeneous sample, which may affect generalizability.

1. Training Teachers in the Field of Literacy in Schools

Improving literacy achievement among elementary students remains an ongoing challenge for educational systems worldwide. International assessments such as the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) continue to reveal variations in student reading performance across countries, with some nations experiencing declines in literacy outcomes (Mullis et al., 2017). These findings highlight the importance of understanding the factors that contribute to effective literacy instruction and the role of teacher preparation in supporting student learning outcomes.

There is broad consensus in the literature that teacher quality is among the most important school-related factors influencing student achievement (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017; Sims et al., 2021). Research suggests that both teacher knowledge and instructional practices contribute to student reading outcomes, particularly when working with diverse student populations who bring different life experiences, language skills, and prior knowledge to the classroom (Monte-Sano et al., 2014). This diversity requires teachers to employ adaptive literacy teaching methods tailored to varied student needs.

One of the primary challenges facing educational systems is providing effective professional development (PD) for teachers that translates into improved classroom practice (Kraft et al., 2018). The goal of this study was to examine the effectiveness of PD in literacy among elementary school teachers based on changes in content knowledge (CK—what teachers know about literacy) and pedagogical content knowledge (PCK—how to teach literacy effectively). In addition, teachers’ degree of practical implementation and its impact on their literacy self-efficacy were examined. The proposed PD program links theory with practice and provides lesson plans that demonstrate this linkage. The proposed PD model integrates theory with practice through structured lesson plans and coaching support, addressing identified gaps in traditional professional development approaches.

As with many countries worldwide, schools in Israel are currently characterized by heterogeneous populations with different needs; despite the efforts of the education system, most teachers have not received sufficient PD in the literacy field. Studies of teachers conducted worldwide have identified gaps in the up-to-date knowledge of theories and models in reading comprehension, as well as difficulties in the implementation of research-based strategies and practices. Gaps also occur in the relationship between teacher knowledge and teacher self-efficacy, especially in the field of literacy training.

2. The Israeli Educational Context

Israeli preservice teacher education demonstrates significant gaps in literacy-specific preparation. Teacher education programs combine disciplinary and pedagogical content in four-year programs, with the basic pedagogical component comprising only 24–30 h annually of educational studies, research methodology, and pedagogical studies with supervised practicum (TIMSS 2015 Encyclopedia, 2015). Critically, there is no specific requirement for comprehensive literacy instruction training during preservice preparation, leaving many elementary teachers inadequately prepared for the complex demands of literacy instruction. The Israeli educational context presents unique challenges for literacy professional development that underscore the importance of targeted, content-specific training programs. All primary and lower secondary school teachers in Israel are required to undergo 60 h of in-service training per year, with at least half of it in their professional domain (TIMSS 2015 Encyclopedia, 2015). However, this requirement does not mandate literacy-specific training, allowing teachers to fulfill these hours across various subject areas without necessarily addressing literacy instruction competencies. Recent evidence underscores the urgency of addressing these training gaps. The 2021 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) revealed alarming declines in Israeli fourth-grade literacy levels, with Israel regressing to its 2001 literacy performance after two decades of gradual improvement, marking a 20-point decline and ranking among the most significant drops measured internationally (Mullis et al., 2023), highlighting a fundamental challenge in the system.

Recent systematic reviews have identified several critical gaps in the professional development literature that our study addresses. First, research on literacy-specific professional development remains fragmented, with nearly half of reading comprehension PD studies occurring with elementary students, while minimal research exists in early elementary and secondary levels (Rice et al., 2024). Second, while meta-analytic evidence demonstrates that professional development has strong effects on teacher self-efficacy in STEM disciplines (effect size g = 0.64) (Zhou et al., 2023), comparable systematic research in literacy contexts remains limited. Third, there is relatively little research that explores the relationship between teacher self-efficacy and professional development practices (Larsen & Bradbury, 2024), particularly regarding how implementation levels mediate these relationships. These gaps are particularly concerning given that schools cannot improve troubling trends in student literacy without investing in meaningful, sustained professional learning about the science of reading for teachers (Learning Forward, 2024). Our study addresses these gaps by examining the specific mechanisms through which literacy-focused professional development influences teacher knowledge, self-efficacy, and classroom implementation in elementary settings.

3. Teachers’ Knowledge

3.1. Defining Content Knowledge and Pedagogical Content Knowledge

There are essentially two types of teacher knowledge: Content Knowledge (CK) and Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK) (Shulman, 1986). Content Knowledge refers to teachers’ deep understanding of the subject matter they teach—in literacy contexts, this includes knowledge of language structures, phonemic awareness principles, vocabulary development, and reading comprehension processes (Ball et al., 2008). Simply put, CK represents what teachers know about reading and writing as academic disciplines.

Pedagogical Content Knowledge, however, goes beyond subject matter expertise to encompass how to teach that content effectively. PCK represents the unique blend of content and pedagogy that makes teaching a distinct profession—it is ‘the knowledge that distinguishes the expert teacher from the content expert’ (Ball et al., 2008, p. 389). In literacy instruction, while CK might include understanding how phonemic awareness develops, PCK involves knowing how to sequence phonics instruction for different learners or recognizing when a student’s reading difficulty stems from decoding versus comprehension challenges.

PCK is defined by three primary characteristics: (a) pedagogical content knowledge is the teachers’ knowledge about the best methods to teach the field of content, whether by using good analogies, examples, explanations, or demonstrations, (b) content-pedagogical knowledge that includes higher processes of understanding the teaching process and how it is implemented with students; that students from different backgrounds and with different learning skills can create a heterogeneous class that requires the teacher to diversify and change her teaching methods according to students’ needs, and (c) familiarity with effective strategies that help reorganize the students’ understanding (Shulman, 1986).

3.2. Research Evidence on Teacher Knowledge in Literacy

Recent empirical research has demonstrated the critical importance of both knowledge types in literacy teaching. McCutchen et al. (2002) found that teachers’ linguistic knowledge significantly predicted their classroom practices and student learning outcomes in early literacy. Similarly, Piasta et al. (2009) showed that teachers’ knowledge of literacy concepts was linked to student reading growth, particularly when combined with effective instructional practices. The distinction between CK and PCK is particularly relevant for professional development design, as effective literacy PD must address both domains simultaneously to translate teacher understanding into effective classroom practices.

4. Teachers’ Self-Efficacy in Literacy

4.1. Theoretical Foundations of Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy is the belief in one’s abilities to accomplish desired outcomes, powerfully affecting people’s behavior, motivation, and, ultimately, their success or failure (Bandura, 1997). Guskey and Passaro (1994) defined teachers’ self-efficacy as a belief or conviction that they can affect the way students learn and the learning quality, even with struggling or unmotivated students (Guskey & Passaro, 1994). Other studies have shown that teachers’ self-efficacy is also associated with successful assimilation of literacy skills through effective teaching practices and class management (Gibson & Dembo, 1984; Midgley et al., 1989) and with higher academic student achievements (Webb & Ashton, 1986; Ross, 1994). Bandura (1997) argued that the self-efficacy of teachers arises from four sources: (a) expertise and mastery of knowledge, (b) indirect experience, (c) social persuasion, and (d) emotional state. However, he emphasized that expertise is the strongest source for accumulating knowledge and affecting the sense of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1986).

4.2. Self-Efficacy as a Mediator in Professional Development

Recent large-scale international research has further clarified the mediating role of teacher self-efficacy beliefs between professional development quality and instructional effectiveness. Yoon and Goddard (2023), analyzing data from 97,729 teachers across 45 countries, demonstrated that teacher self-efficacy beliefs significantly mediate the relationship between PD quality and three key instructional practices: clarity of instruction, cognitive activation, and classroom management. This research provides empirical support for the theoretical assumption that self-efficacy beliefs serve as a crucial mechanism through which professional development experiences are translated into classroom practice.

5. Effective Professional Development

5.1. Core Features of Quality Professional Development

PD improves teaching methods when the program is (a) consistent, intense, continuous, and content-focused, (b) allows active learning, (c) is assimilated into the work, (d) is coherent and directly related to the daily practice in class and the curriculum, and (e) creates an effective learning environment for teachers in communities and learning teams (Darling-Hammond et al., 2009; Desimone & Pak, 2017). Cirkony et al. (2022) reviewed 12 PD studies and identified eight features of effective PD: collaboration, active learning and reflection, content and pedagogy in context, sustained duration, coaching, external expertise, models and modeling, and audience and alignment. These characteristics emphasize the focus on understanding how teachers’ learning occurs, in addition to providing content and work methods, and the transition from ‘professional development’ to ‘professional learning’.

5.2. International Validation of PD Components

International research has validated these core features through large-scale empirical studies. Yoon and Goddard (2023) confirmed that PD programs incorporating content focus, active learning, coherence, duration, and collective participation significantly predict both teacher self-efficacy beliefs and instructional effectiveness. Their findings suggest that the quality of PD, as measured by these five core features, serves as a significant predictor of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs, which in turn influences instructional practice.

Over the past two decades, many schools worldwide have employed literacy experts to continuously improve the quality of teaching, provide teachers with up-to-date teaching methods, and lead literacy programs in schools (Desimone & Pak, 2017; Shearer et al., 2018).

6. Professional Development and Teacher Self-Efficacy in Literacy

Teacher self-efficacy was first identified as the most significant variable for assimilating change among teachers in seminal research conducted by the RAND Corporation (Berman et al., 1977). This foundational finding has endured across nearly five decades of subsequent research and remains central to contemporary understanding of professional development effectiveness. Recent meta-analytic evidence continues to validate this core insight: Zhou et al. (2023) demonstrated strong effects of professional development on teacher self-efficacy across STEM disciplines (effect size g = 0.64), while Yoon and Goddard’s (2023) large-scale international study of 97,729 teachers across 45 countries confirmed that teacher self-efficacy beliefs significantly mediate the relationship between PD quality and instructional effectiveness. Thus, the RAND study’s identification of self-efficacy as a critical mechanism for teacher change has been consistently reinforced by decades of empirical research, establishing it as a fundamental principle in professional development design.

Although many studies have examined teachers’ self-efficacy and its relationship with various aspects of teaching and education, few studies have dealt with literacy-specific teacher self-efficacy (e.g., Graham et al., 2001; Tschannen-Moran & McMaster, 2009). However, teachers’ sense of self-efficacy is intensified when their basic or ongoing training includes the acquisition of specific and up-to-date disciplinary knowledge.

Contemporary meta-analytic evidence demonstrates that sustained professional development programs with active teacher engagement significantly enhance teacher self-efficacy. Zhou et al.’s (2023) meta-analysis of experimental studies revealed strong effects of professional development on teacher self-efficacy (effect size g = 0.64), while Yoon and Goddard’s (2023) international study of 97,729 teachers across 45 countries confirmed that high-quality PD programs incorporating active learning and sustained duration significantly predict teacher self-efficacy beliefs.

Recent experimental evidence further supports the relationship between professional development modality and self-efficacy outcomes. Mastrothanasis and Kladaki (2025) conducted a controlled study of 204 teachers in Greece, comparing drama-based reading instruction approaches (Reader’s Theatre and Dramatic Storytelling) with traditional methods. Their findings demonstrated large effect sizes (Cohen’s d = 1.21 and 1.15, respectively) for teachers using experiential, hands-on approaches compared to conventional instruction. Importantly, their study reinforces that the type of professional development experience—particularly those involving active implementation—significantly influences teacher confidence development. This experimental evidence aligns with our theoretical framework suggesting that implementation frequency and modality are critical mediators of professional development effectiveness.

Numerous studies have shown that despite the rich PD provided to teachers, the primary difficulty facing this process is the program’s assimilation in the classrooms and the knowledge preservation among teachers and schools (Tschannen-Moran & McMaster, 2009). In other words, although teachers receive high-quality training, they have difficulty maintaining and continuing the process in school after completing a PD program. However, it appears that to create actual change, teachers must continue to use the knowledge they have acquired and assimilate it in their classrooms years after receiving PD training.

A model of teacher change designed by Guskey (1986) argued that a major factor in the failure of most PD programs is that they do not consider factors that motivate teachers to be active in the programs and implement the knowledge they acquired. Among these factors, studies found that teachers’ self-efficacy is a significant factor contributing to the implementation of new pedagogical tools (e.g., Guskey, 1988). That is, teachers’ self-efficacy may motivate teachers and encourage them to assimilate knowledge into practice.

Furthermore, a study by Tschannen-Moran and McMaster (2009) examined the contribution of a PD program to increasing teachers’ self-efficacy and implementing a new teaching strategy in the field of literacy through different PD programs. In their study, four PD programs were examined: (1) knowledge only—teachers participated in a three-hour workshop on a reading strategy; (2) knowledge and modeling—teachers participated in a three-hour workshop that included a reading strategy and demonstrations of the strategy; (3) knowledge, modeling, and practice—teachers participated in a workshop identical to the knowledge and modeling workshop (type 2) but to which an hour and a half of practice was added; the practice included working in small groups, holding discussions about the manner and the practical implications of implementing the strategy in the classroom; and (4) knowledge, modeling, experience and coaching—in addition to the training and experience (type 3), the teachers underwent a coaching process in the weeks following the workshop to examine the strategy implementation with a coach’s guidance in the classroom.

The results of Tschannen-Moran and McMaster (2009) showed that in all programs, an increase in teachers’ general and literacy self-efficacy was observed. Moreover, the program with the greatest impact on teachers’ self-efficacy included practice and support from a coach when implementing the new strategy in the teacher’s classroom (type 4). By providing the added support of a coach, the level of teacher self-efficacy increased, as did the degree of reading strategy assimilation in the classroom (Tschannen-Moran & McMaster, 2009). Thus, the most effective way to help teachers create real change in their sense of literacy self-efficacy in the classroom is through continuing guidance after PD training. Such guidance encourages teachers to continue the process of change initiated during a PD program, enables the practical implementation of the knowledge acquired during PD, and even fine-tunes the application of the acquired knowledge according to the class’s needs.

To summarize, Tschannen-Moran and McMaster (2009) identifies several factors that may help teachers teach effectively, improve the performance of their students, and change their level of knowledge and feelings of self-efficacy. Along with these supporting factors are the challenges of creating effective, high-quality PD programs that provide teachers with practical tools for assimilating the acquired knowledge in their classroom.

Proposed Teachers’ Professional Development Program Model

The PD model in this study was designed to provide comprehensive training in literacy for elementary school teachers. The model integrates three key components (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

The Teachers’ Professional Development Model.

- Content Knowledge (CK): Focusing on theory-based understanding of reading and reading comprehension development. This includes up-to-date models regarding reading skills such as vocabulary, fluency, and cognition/metacognition.

- Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK): Incorporating research-based reading strategies, evidence-based practices, and effective teaching methods.

- Practice CK: Providing concrete lesson plans that translate theoretical models into practical classroom activities. These lesson plans demonstrate the integration of theory and pedagogy with specific activities, texts, presentations, strategies, and classroom games.

The model is distinctive in its emphasis on providing teachers with not only theoretical knowledge but also structured opportunities to implement this knowledge in their classrooms with coaching support. This implementation component addresses a critical gap in traditional PD programs, which often fail to bridge the divide between theory and classroom practice

The PD model was evaluated on three key dimensions:

- Will the PD model lead to changes in teachers’ literacy knowledge?

- Will the PD model lead to changes in teachers’ sense of self-efficacy?

- Does the degree of practical implementation of PD practices by teachers affect their literacy self-efficacy?

7. Comparison with Existing Professional Development Models

To situate our research within the broader literature, it is useful to compare our PD model with established frameworks. Like Desimone’s (2009) five core features model, our approach emphasizes content focus, active learning, and sustained duration. However, our model extends this framework by explicitly integrating three knowledge domains: content knowledge (CK), pedagogical content knowledge (PCK), and practical implementation—similar to building a bridge where each component serves a distinct structural purpose.

Our model aligns with Tschannen-Moran and McMaster’s (2009) four-tier approach but differs in its systematic integration of all three components from the outset. While their model progresses sequentially, our approach can be likened to a three-legged stool where all components must be present simultaneously for stability.

As Kennedy (2016) noted, traditional PD often fails because it focuses on design features rather than underlying theories of action. Our model addresses this by providing not just knowledge transmission but concrete implementation support with coaching—bridging the research-to-practice gap that Kennedy identified as critical for effectiveness.

8. Methods

8.1. Participants and Procedure

The data were collected during the 2020–2021 school year. The teachers were assessed during pre-PD in November 2020, and the post-measurements were collected in May–June 2021. Second- and third-grade language teachers from 33 schools in Southern Israel participated in the study, including state and religious schools with diverse socioeconomic statuses. The teachers participated in a PD through the Pisgah Center in their city as part of the district and school participation in the research. The sample included 82 teachers, of whom 80 were women (97.56%) and two were men (2.44%). The participants’ ages ranged from 24 to 61 years (M = 39.48, SD = 9.51). Teachers were not pre-assigned to implementation groups in advance. All participants experienced the same PD structure and content. Participants were not selected through random sampling as this study included all teachers in the district who participated in the professional development (PD) program. At the end of the program, teachers reported how many lessons they had implemented. Implementation levels varied across participants due to personal circumstances, school constraints and schedules. These variations arose independently of the research team and were not influenced by any experimental manipulation. To examine the relationship between implementation frequency and self-efficacy gains, participants were divided post hoc into two groups based on the median number of lessons implemented (Mdn = 4): low implementation group (0–4 lessons, n = 65) and high implementation group (5–12 lessons, n = 17). Prior to change score analysis, we confirmed that these groups did not differ significantly in baseline self-efficacy levels (t(80) = 1.10, p = 0.275), ensuring that observed differences in self-efficacy gains could be attributed to implementation effects rather than initial group differences.

Sample size estimations were performed using G*Power software, version 3.1 (Faul et al., 2007, 2009). For the paired-sample t-tests examining knowledge and self-efficacy changes, parameters included α = 0.05, power = 0.95, and medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.5). For the independent samples t-test comparing change scores between implementation groups, parameters included α = 0.05, power = 0.80, and medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.5). Power analyses indicated that our sample size of 82 participants provided adequate power for all planned analyses.

8.2. Measures

(1) Demographic background questionnaire: This questionnaire examined teachers’ backgrounds, such as age, gender, teaching seniority, participation in previous courses, and information about the school (in which grade the teachers teach, whether the teacher is a homeroom teacher, etc.). The questionnaire was administered online at the beginning of the study and consisted of 12 items covering both personal and professional information, including years of education, years of teaching experience, and current teaching responsibilities.

(2) Perception and Sensations Questionnaire—Literacy efficacy. (TSELI, translated and adapted by Lipka, 2017, based on Tschannen-Moran & Johnson, 2011). The Teacher Self-Efficacy in Literacy Instruction (TSELI) scale was developed based on Bandura’s (1997) model of self-efficacy. While the original questionnaire examined self-efficacy across various literacy teaching domains and included 27 items covering both reading and writing instruction, the current study utilized a modified Hebrew version that focused specifically on reading comprehension and vocabulary instruction. This adapted questionnaire included 12 items tailored to the professional development program content. Teachers rated their confidence in performing specific literacy instruction tasks on a 9-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not confident at all) to 9 (very confident). Example items included: “To what extent are you able to teach your students how to draw inferences from a reading passage?”, “To what extent are you able to expose students to new words in various contexts and different domains?”, and “To what extent are you able to teach vocabulary in order to deepen reading comprehension?” The questionnaire was administered online at both pre- and post-PD timepoints. The original measure demonstrated strong construct validity, supported by factor analysis that identified teacher’s sense of efficacy for writing and oral reading instruction (Tschannen-Moran & Johnson, 2011). The Hebrew version adapted by Lipka (2017) underwent translation, back-translation, and expert review by bilingual literacy researchers to ensure conceptual and linguistic equivalence and was used in several previous studies. The current modified version maintained strong psychometric properties, with the tool’s reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) α = 0.93 at post-measurement. The adapted scale also demonstrated strong construct validity, using a factor analysis conducted on the current sample. The analysis yielded a two-factor structure, aligning with key conceptual domains of literacy instruction and the original scale (see Table 1). The first factor reflected efficacy in vocabulary and comprehension instruction, while the second captured efficacy in oral reading and differentiated instruction. Moreover, the tool’s reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) at the time they were collected at the end of the study was α = 0.93.

Table 1.

Factor structures of translated version of the Perception and Sensations Questionnaire—Literacy efficacy (TSELI).

(3) Teachers’ knowledge questionnaires: Pre- and post-PD knowledge level questionnaire (Osman (2017), translated into Hebrew and adapted for PD programs and Shulman’s knowledge curricula). These were retrospective self-report questionnaires administered online after completing the teacher PD program. This measure uses retrospective pre–post format, in which participants rated both their pre-program and post-program knowledge at the end of the intervention. This approach has been shown to reduce response-shift bias and enhances the accuracy of self-assessment in learning contexts and educational programs (e.g., Bhanji et al., 2012; Howard et al., 1979). The questionnaires dealt with teachers’ level of knowledge in various literacy fields and the change in knowledge following the PD program. The teachers were asked to rate their level of knowledge on a scale of 1 (weak) to 4 (excellent). Two versions were administered to examine the teachers’ knowledge:

a. Pre-professional development knowledge level questionnaire: A five-item questionnaire that examined the teachers’ level of knowledge prior to the continuing education program. Teachers were asked to retrospectively evaluate their knowledge level before participating in the PD. Example items included: ‘Rate your level of knowledge before the PD program regarding the content presented in the PD’, ‘Rate your level of knowledge before the PD program regarding teaching methods of the strategies presented in the PD’, and ‘Rate your level of knowledge before the PD program regarding the main aspects of literacy instruction covered in the PD’. Tool reliability: α = 0.94. Also, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted to evaluate the construct validity of the teachers’ pre-PD knowledge questionnaire. The analysis revealed a single-factor solution explaining 81.06% of the variance, with strong item loadings ranging from 0.85 to 0.93, supporting the one-dimensionality of the measure (KMO = 0.87).

b. Post-professional development knowledge level questionnaire: A five-item questionnaire assessed the teachers’ knowledge after the continuing education program. The questionnaire used parallel wording to the pre-PD knowledge questionnaire but asked teachers to rate their current knowledge level after completing the PD. Example items included: ‘Rate your level of knowledge after participating in the PD regarding the content presented in the PD’, ‘Rate your level of knowledge after participating in the PD regarding teaching methods of the strategies presented in the PD’, and ‘Rate your level of knowledge after participating in the PD regarding the main aspects of literacy instruction covered in the PD’. Tool reliability: α = 0.95. An exploratory factor analysis was conducted to evaluate the construct validity of the teachers after the PD knowledge questionnaire. A single-factor solution emerged, explaining 83.12% of the total variance, with strong factor loadings from 0.89 to 0.94 (KMO = 0.87).

All questionnaires were administered via the Qualtrics online survey platform. Teachers received unique login credentials and were given a one-week period to complete each questionnaire at the designated timepoints. For the retrospective knowledge assessment, clear instructions were provided to help teachers distinguish between their knowledge levels before and after the PD program.

Table 2 presents details about the pre- and post-PD measures that were collected.

Table 2.

Teacher Questionnaires According to Their Time of Delivery: 2020–2021.

9. Data Analysis

We used two statistical techniques to examine our research questions. Dependent sample t-tests compared teachers’ knowledge before and after PD—this test determines whether observed improvements are statistically significant (real changes rather than chance). Independent sample t-tests compared self-efficacy change scores between implementation groups—this approach directly examines whether teachers who implemented more PD lessons showed greater improvement than those who implemented fewer lessons. Change scores were calculated as post-PD minus pre-PD self-efficacy for each teacher. Statistical significance (p < 0.05) indicates less than 5% probability that results occurred by chance.

Procedure

The Ministry of Education district supervisors introduced the study to all schools in the district. Principals whose schools had no other literacy PD scheduled for that academic year were encouraged to participate. This recruitment approach ensured that the PD program would be the only literacy-focused professional development teachers received during the study period, minimizing potential confounding variables.

The teachers participated in four parallel PD groups at the PD Center. The courses were held through synchronous Zoom meetings. Literacy teachers, and literacy instructors of grades 2–3 from the schools participating in the 30-h PD program.

Prior to the first session, teachers completed the demographic questionnaire and the pre-PD literacy self-efficacy measure (see study design in Figure 2). Teachers kept implementation logs documenting when they were implementing PD lessons, and brief reflections on the implementation. This allowed for the degree of implementation across participants to be tracked.

Figure 2.

Study Design.

At the conclusion of the PD program, teachers completed the post-PD literacy self-efficacy measure and the retrospective knowledge questionnaires to assess both pre- and post-PD knowledge levels. This retrospective approach was chosen to ensure a consistent frame of reference when evaluating knowledge change, as teachers might not have been aware of what they did not know at the beginning of the program pre-PD literacy self-efficacy measure. All data collection procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Department of Education at the University of Haifa, and informed consent was obtained from all participants before data collection began.

10. Results

Background Measures

As part of the questionnaires administered during the analysis of the PD program model, several teachers’ background measures were collected, such as age, number of years of education, seniority in teaching, which grade the teachers teach, and the number of frontal teaching hours (see descriptive statistics in Table 3).

Table 3.

Demographic Characteristics and Group Comparisons of Participating Teachers.

To determine whether there were potential differences in the background data of teachers who taught different grades (grades 2–3 or 4–5), one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted. These tests showed that no significant differences were found in the background measures between teachers in different grades (see the variance test values in Table 3). In light of the lack of differences between the groups in the background measures, the teachers were treated as a single group, regardless of the grade (2 or 3) in which they taught.

11. Change in Teachers’ Levels of Knowledge

- Research Question 1: Will a PD for teachers in literacy lead to changes in teachers’ literacy knowledge?

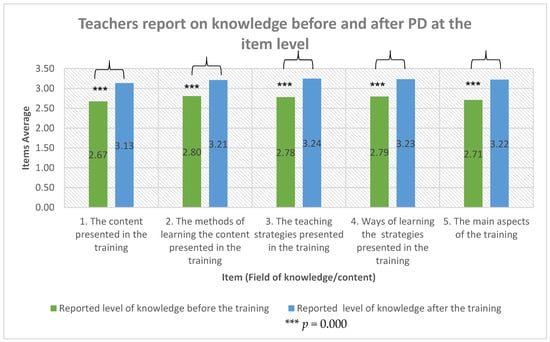

The first research question deals with teachers’ self-reports of a change in knowledge after a PD program on establishing reading and promoting reading comprehension. For this purpose, the teachers’ knowledge levels were examined from a retrospective perspective: At the end of the PD program, the teachers were asked to report on the CK and PCK that they had at the beginning and end of the PD program. To answer this research question, a t-test for dependent samples was used to examine the differences between knowledge level reports before and after the PD program. The overall reported level of various fields of the teachers’ knowledge after the PD program (according to Shulman’s knowledge curricula) was significantly higher (M = 3.21, SD = 0.59) than the reported level of knowledge at the beginning of the PD program (M = 2.75, SD = 0.70) [t(81) = 6.33, p = 0.000]. Specifically, the teachers retrospectively rated their level of knowledge prior to the PD program on average between 2 = ‘ok’ and 3 = ‘good’, whereas they rated their knowledge level after the PD program on average between 3 = ‘good’ and 4 = ‘excellent’.

- Examining Differences at the Item Level:

Further differences were examined in the teachers’ reported level of knowledge before and after the PD at the item level. To examine these differences, t-tests for dependent samples were conducted for each of the 5 items. The items reported by the teachers that indicated different types of knowledge after the PD program were significantly higher than before the PD program. The fields of knowledge dealt with the content presented in the PD (various literacy skills such as: decoding, reading accuracy, reading fluency, vocabulary, and reading comprehension), different strategies for literacy skills, and the different learning methods presented in the PD. Table 4 presents the comparisons between the items according to the time of measurement. Figure 3 shows the change in knowledge levels and the differences in teachers’ reports at the item level.

Table 4.

Pre–Post-Professional Development Knowledge Gains by Content Domain.

Figure 3.

Knowledge Levels Before and After the Professional Development Program.

12. Change in Teachers’ Self-Efficacy

- Research Question 2: Will PD for teachers in literacy lead to changes in the sense of self-efficacy among teachers?

To examine changes in teachers’ literacy self-efficacy following the PD program across the entire sample of participants, we conducted a 2 × 2 ANOVA with repeated measures. The analysis revealed a significant main effect of time (F[1,80] = 6.02, MSE = 2.00, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.07), indicating that teachers’ literacy self-efficacy significantly increased from pre-PD (M = 5.45, SE = 0.09) to post-PD (M = 5.72, SE = 0.10) across all 82 teachers in the study (see Figure 4). This finding demonstrates that the PD program was effective in enhancing teachers’ confidence in their ability to deliver literacy instruction, regardless of their subsequent implementation levels.

Figure 4.

Teachers’ Report on Knowledge Levels Before and After PD at the Item Level.

13. The Degree of Implementation and Its Effect on Teachers’ Literacy Self-Efficacy

- Research Question 3: Does the degree of practical implementation of PD practice by teachers affect their literacy self-efficacy?

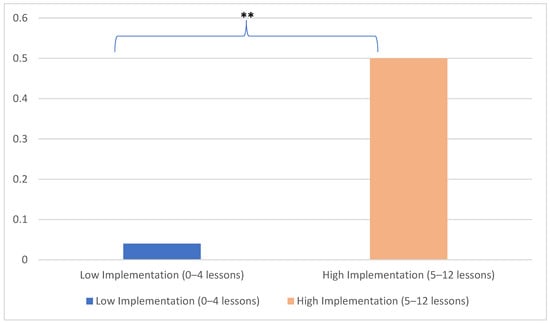

To examine whether the level of PD implementation affected teachers’ gains in literacy self-efficacy, we calculated individual change scores (post-PD self-efficacy minus pre-PD self-efficacy) for each teacher. Teachers were then categorized into two implementation groups based on the number of PD lessons they implemented: low implementation (0–4 lessons, n = 65) and high implementation (5–12 lessons, n = 17). Table 5 presents teachers’ self-efficacy scores before and after the PD, along with the corresponding change scores, categorized by implementation level. We used an independent samples t-test to compare change scores between implementation groups. This approach directly tests whether implementation level affects the magnitude of self-efficacy improvement while maintaining adequate statistical power with our sample size. Teachers in the high implementation group demonstrated significantly greater improvements in literacy self-efficacy (M = 0.50, SD = 0.55) compared to teachers in the low implementation group (M = 0.04, SD = 0.58), t(80) = 2.95, p = 0.004, Cohen’s d = 0.80 (see Figure 5).

Table 5.

Teachers’ Self-Efficacy Change Scores by Implementation Level.

Figure 5.

Teachers’ Self- Efficacy Change Scores by Implementation Level. Note. ** p < 0.01.

This represents a large effect size according to Cohen’s (1988) conventions, indicating that teachers who implemented 5 or more PD lessons experienced meaningfully greater gains in their confidence to deliver effective literacy instruction.

The magnitude of this difference is substantial: while teachers implementing fewer lessons showed minimal change in self-efficacy (equivalent to moving from “somewhat confident” to “somewhat confident” on the 9-point scale), teachers implementing more lessons showed meaningful improvement (equivalent to moving from “somewhat confident” to “quite confident”). These findings provide strong evidence for a dose–response relationship between PD implementation and self-efficacy gains. Teachers who applied the PD strategies more frequently in their classrooms not only maintained their knowledge but also developed greater confidence in their literacy instruction abilities.

14. Discussion

This study examined the impact of a proposed teacher PD program that promotes reading and reading comprehension skills on teachers’ knowledge and levels of literacy self-efficacy. The study aimed to expand the scientific research on effective PD for literacy teachers and create a change in teachers’ knowledge, pedagogy, and classroom practice. Knowledge and pedagogical theories in the field of literacy have advanced over the years. However, because teachers’ functioning also affects student performance, it is important to establish research-based theories and tools in teaching and PD programs (e.g., Kratochwill et al., 2007; Ysseldyke & McLeod, 2007). In particular, this study aimed to examine how teachers can be provided with optimal PD programs that can foster significant changes in both the level of teachers’ knowledge and pedagogy in the classroom. This study employed a change score analysis approach to examine dose–response relationships, which provides direct evidence of how implementation frequency affects professional development benefits.

- Research Question 1: Will a PD for teachers in literacy lead to changes in teachers’ literacy knowledge?

Teachers demonstrated significant knowledge gains across all literacy domains (M = 2.75 to M = 3.21), moving from ‘okay–good’ to ‘good–excellent’ levels. This finding reinforces that well-designed PD can effectively enhance both content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge in literacy instruction.

The first research question addresses the impact of a proposed PD program for establishing reading and promoting reading comprehension on the change in teachers’ knowledge, self-reported retrospectively. As part of this study, an evidence-based teachers’ PD program was developed, designed to promote theoretical CK in literacy, introduce strategies in reading and reading comprehension (PCK), and achieve their implementation in the field.

A basic principle of the proposed PD program was striving for a change in teachers’ CK and PCK. The CK theoretical knowledge included the content learned in the PD (e.g., knowledge of literacy skills—establishing reading, reading accuracy, and reading fluency). The PCK included strategies, monitoring, assessments, best practices in reading and reading comprehension, and the way these were learned. The teachers reported significantly higher levels of knowledge after PD than before PD in all fields of CK and PCK examined. These findings are consistent with Shulman’s (1986) model, which reinforces the development of different types of knowledge in teacher PD programs and posits that these two types of knowledge are necessary to produce effective and high-quality teacher PD that may help and lead to improved student performance in general and in heterogeneous classrooms in particular (Shulman, 1986).

Our findings on the relationship between professional development and teacher knowledge, contribute to the growing body of research on literacy teacher knowledge development. Similarly to studies by Brady et al. (2009) and McCutchen et al. (2009), our results demonstrate that targeted professional development can successfully increase teachers’ content knowledge in literacy. Both of these previous studies documented significant knowledge gains following intensive PD, which aligns with our finding that teachers reported significantly higher levels of knowledge after completing the PD program.

- Research Question 2: Will PD for teachers in literacy lead to changes in the sense of self-efficacy among teachers?

Teachers showed significant improvements in literacy self-efficacy (M = 5.45 to M = 5.72), confirming that quality PD enhances teachers’ confidence in their instructional capabilities.

In addition to the change in the types of teacher’s knowledge, this study addressed the development and change in teachers’ sense of self-efficacy in the literacy context following the proposed PD program. To this end, the second research question concerns the impact of the proposed program on a sense of literacy self-efficacy at several levels. First, differences were examined between the sense of literacy self-efficacy among all teachers before and after the PD program. The results showed that the teachers’ sense of literacy self-efficacy was significantly higher at the end of the PD program than at the beginning. This finding supports the research literature indicating that high-quality PD programs for teachers may lead to an increase in teachers’ sense of literacy self-efficacy (e.g., Henson, 2001). Our findings align with recent large-scale international research on the mediating role of teacher self-efficacy beliefs. Yoon and Goddard (2023) found that teacher self-efficacy beliefs significantly mediate the relationship between PD quality and instructional effectiveness across diverse international contexts.

This finding receives additional support from recent experimental research demonstrating similar patterns across different professional development modalities. Mastrothanasis and Kladaki’s (2025) controlled study of drama-based literacy instruction found comparably large self-efficacy improvements (d = 1.21–1.15) when teachers engaged in hands-on, experiential learning approaches. The consistency of large effect sizes across different PD modalities—whether literacy-specific training (our study) or drama-based methodologies (Mastrothanasis & Kladaki, 2025)—suggests that the critical factor may be the experiential, implementation-focused nature of the professional development rather than the specific content area. This convergent evidence from diverse educational contexts strengthens confidence in the generalizability of self-efficacy improvements through well-designed professional development experiences.

The consistency between our Israeli literacy-focused findings and their international cross-domain evidence suggests that self-efficacy may serve as a universal mechanism through which PD influences teaching practice, regardless of specific educational context or subject matter. This sense of self-efficacy is important not only for maintaining knowledge at the teacher level, but also for providing students with the confidence to practice it in their classroom/level (e.g., Ross, 1994; Webb & Ashton, 1986). Furthermore, the knowledge change was examined on the item level (five items).

- Research Question 3: Does the degree of practical implementation of PD practices by teachers affect their literacy self-efficacy?

The analysis provides compelling evidence for a strong dose–response relationship between professional development implementation and teacher self-efficacy gains. Teachers who implemented 5 or more PD lessons demonstrated significantly greater improvements in literacy self-efficacy (M = 0.50) compared to those who implemented fewer lessons (M = 0.04), with a large effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.80). This finding reveals important insights into the minimum implementation threshold necessary for meaningful professional development benefits.

The contrast between groups is particularly striking—while teachers implementing 0–4 lessons showed virtually no self-efficacy improvement (0.4% change on the 9-point scale), those implementing 5+ lessons experienced substantial gains (5.6% improvement). This suggests a critical implementation threshold of approximately 5 lessons, below which professional development benefits remain minimal, but above which meaningful confidence gains emerge.

These results align closely with Bandura’s (1997) self-efficacy theory, which identifies mastery experiences as the most powerful source of efficacy beliefs. Teachers who implemented more lessons accumulated more successful experiences with the new literacy strategies, thereby strengthening their confidence in their instructional capabilities. The threshold we observed may represent the point at which teachers transition from “trying something new” to “experiencing competence,” a qualitative shift that fundamentally enhances professional confidence.

The findings build upon Tschannen-Moran and McMaster’s (2009) work, which demonstrated that PD formats including hands-on practice and coaching support produce greater self-efficacy gains. However, our study provides more precise guidance by identifying a specific implementation frequency threshold. This nuanced understanding moves beyond the general principle that “practice matters” to specify that teachers need approximately 5 coached implementation experiences to achieve meaningful self-efficacy benefits.

The critical importance of implementation frequency identified in our study finds strong support in recent experimental evidence. While our research identified a threshold effect at 5+ lessons, Mastrothanasis and Kladaki (2025) demonstrated that even 8 weeks of consistent implementation of drama-based approaches yielded substantial self-efficacy gains (d = 1.21–1.15). Their experimental design, comparing active implementation approaches with traditional methods, provides complementary evidence that sustained, hands-on professional development experiences—regardless of specific methodology—produce meaningful teacher confidence improvements. This cross-national validation reinforces our conclusion that implementation frequency and quality are universal principles in effective professional development design.

Furthermore, our study contributes to the literature by examining these relationships in the Israeli educational context, where research on literacy teacher knowledge has been more limited. The work of Snow et al. (2005) emphasized that effective literacy instruction requires teachers to possess content knowledge for teaching reading that includes understanding of language structure, text processing requirements, and reading development. Our findings suggest that these knowledge components, when successfully transmitted through PD and implemented in classrooms, can enhance teacher self-efficacy in diverse educational settings.

While Moats’ (1994) foundational work highlighted significant gaps in teachers’ understanding of language structure, our study provides a hopeful perspective on how these gaps can be addressed through well-designed PD that bridges research and practice. By focusing on both knowledge development and implementation, our model addresses what Piasta et al. (2009) identified as the critical pathway through which teacher knowledge affects student outcomes—the translation of knowledge into effective classroom practice.

This study expands the knowledge on the impact of a proposed research-based PD program in the field of literacy on changes in the types of teachers’ knowledge and on the literacy self-efficacy of teachers at different levels of implementation in the field. On a practical level, this understanding encourages teachers to participate in training based on their experience in the field. In turn, high-quality PD programs are created that lead to significant and real change among many teachers and students.

The creation of teachers’ PD programs, even in the training stages of preservice teachers, should be encouraged. These programs should be based on models of optimal, research-based continuing education that can be implemented in the field, combine theoretical models in various fields of knowledge and content, and provide practical tools and teacher guidance from the teacher training center to the classroom (Fletcher & Vaughn, 2009; Freeman et al., 2009; Glover & DiPerna, 2007; Kratochwill et al., 2007; O’Connor & Freeman, 2012; Tschannen-Moran & McMaster, 2009; Ysseldyke & McLeod, 2007). It is also important to create a community of colleagues and teachers that fosters fertile ground for discussion, support, and consultation.

Our study contributes to a growing international evidence base demonstrating the critical mediating role of teacher self-efficacy in professional development effectiveness. The convergence of our findings with large-scale international research (Yoon & Goddard, 2023) suggests that enhancing teacher self-efficacy should be considered a universal strategy for improving the translation of professional development into effective classroom practice. This has important implications for educational policy and practice, indicating that PD evaluation frameworks should systematically assess changes in teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs alongside traditional measures of knowledge acquisition and skill development.

Furthermore, if the goal of PD is to change classroom practice, it is important initially to develop teachers’ CK and PCK, as well as their sense of self-efficacy, and to provide tools that will allow them to implement this knowledge in a practical way in their classroom. This study concluded that the actual teaching of five or more lessons using the intervention tools acquired in a PD program can result in a significant change in teachers’ self-efficacy and implementation practices. Future studies should reconstruct these findings and examine different levels of actual program implementation provided in the training (dosage) in the language field, as well as in other content worlds beyond literacy.

15. Practical Implications for Students

These findings have direct implications for student literacy outcomes. For example, a teacher who gains confidence in phonemic awareness instruction (enhanced CK) and learns how to sequence these skills for diverse learners (enhanced PCK) is better equipped to help struggling readers decode unfamiliar words. When this teacher implements at least 5 PD lessons with coaching support, they develop procedural fluency in adapting instruction based on student responses—directly impacting reading achievement.

The threshold effect has direct classroom implications: Teachers implementing fewer than 5 lessons show virtually no self-efficacy improvement (0.4% gain), while those implementing 5 or more lessons demonstrate substantial confidence gains (5.6% improvement). Teachers who reach this threshold are more likely to persist when students struggle, try alternative strategies, and maintain high expectations—all factors that research links to improved student reading outcomes (Ross, 1994; Webb & Ashton, 1986).

16. Recommendations for Practice and Future Research

For Practitioners:

- Design PD programs that integrate all three components (CK, PCK, and implementation) simultaneously rather than sequentially

- Establish a minimum threshold of 5 coached lessons as essential for meaningful self-efficacy benefits, recognizing that fewer lessons yield minimal improvement.

- Include ongoing coaching support during classroom implementation phases

- Measure both knowledge gains and self-efficacy changes as indicators of PD effectiveness.

- Prioritize reaching the 5-lesson threshold over distributing limited coaching time Draw from international evidence on implementation approaches: Research across diverse educational contexts (Israeli literacy training, Greek drama-based instruction) consistently demonstrates that hands-on, experiential professional development produces large self-efficacy gains (Mastrothanasis & Kladaki, 2025). This cross-cultural validation suggests that the principles of sustained implementation and active engagement transcend specific cultural or curricular contexts.

For Researchers:

- Investigate optimal dosage levels by examining implementation frequencies beyond the 5–12 lesson range identified here

- Explore whether the dose–response relationship varies across different literacy domains (e.g., phonics vs. comprehension)

- Examine long-term sustainability of self-efficacy gains and their relationship to student achievement

- Replicate findings across different educational contexts and teacher populations to establish generalizability

For Policy Makers:

- Allocate sufficient time and resources for sustained PD that includes implementation support

- Prioritize coaching components in literacy PD funding decisions

- Consider self-efficacy measures in PD evaluation frameworks alongside traditional knowledge assessments.

- Recognize implementation thresholds in funding formulas—ensure adequate resources for teachers to reach the critical 5-lesson minimum rather than maximizing participant numbers.

17. Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged. Our sample was highly homogeneous in gender (97.5% female), which limits generalizability to male teachers. However, this composition reflects the demographic reality of elementary education, where women represent 94% of pre-primary and 66% of primary teachers globally (UNESCO, 2020), and 78% of primary teachers in Israel (OECD, 2019). Future research should examine potential gender differences in professional development outcomes, though recruitment of male elementary teachers may be challenging given current workforce demographics. Additionally, our findings rely on self-reported measures and retrospective assessments, which may be subject to bias, and were conducted during COVID-19 with virtual delivery, potentially limiting generalizability to traditional in-person formats.

In addition, another potential limitation may be the reliance exclusively on teachers’ self-reported perceptions of knowledge and implementation rather than objective measures such as standardized knowledge assessments or classroom observations. While research shows strong correlations between teacher self-reports and classroom observations (Desimone et al., 2010), and meta-analytic evidence demonstrates strong effect sizes for professional development on teacher self-report measures (Zhou et al., 2023), self-report data may be subject to social desirability bias. Future research should incorporate objective measures such as standardized assessments or classroom observations to provide more comprehensive evaluation of professional development effectiveness.

Also, Shapiro–Wilk tests indicated significant deviations from normality for several variables. Specifically, teacher self-efficacy scores before the PD (Skewness = −0.54, Kurtosis = −0.26), and after the PD (Skewness = −0.77, Kurtosis = 0.61), as well as Knowledge scores before (Skewness = 0.30, Kurtosis = −0.84) and after the PD (Skewness = −0.31, Kurtosis = −0.40). Although retrospective change in knowledge, and knowledge before the PD approximated a normal distribution among participants with large-implementation levels, the raw pre- and post-scores did not. While parametric analyses were employed, this decision was based on prior research indicating that parametric tests such as t-tests and repeated-measures ANOVA are robust to moderate violations of normality when sample sizes exceed 30 (e.g., Kim & Park, 2019; Lumley et al., 2002). It is important to note that the present sample (n = 82) comprised the entire population of teachers who participated in the professional development (PD) program within the district. As such, the sample size could not be increased further, and the study did not rely on random sampling procedures. Furthermore, the research was conducted in an authentic field setting, where educational and logistical constraints naturally shaped the implementation process. While this enhances ecological validity, it also limits experimental control and statistical ideal conditions. Given these constraints, the chosen analyses aimed to balance methodological rigor with the practical realities of real-world educational research. Future studies with larger and more diverse samples may help to confirm and expand upon these findings.

Moreover, the study focus on grades 2–3 literacy instruction and may limits generalizability to other subjects and grade levels. Literacy instruction has unique pedagogical characteristics that may not apply to STEM subjects or secondary education contexts. Future research should examine this professional development model across different domains and grade levels.

A significant methodological limitation is the absence of a control group, which limits the ability to make causal inferences about the professional development program’s effectiveness. While this represents an important constraint, it reflects broader challenges in professional development research, where only a small fraction of studies employ experimental designs due to ethical, logistical, and practical considerations (Rice et al., 2024). The current study did examine different levels of implementation (0–4 vs. 5–12 lessons) and their relationship to self-efficacy, providing some comparison insights, but future research should strive for experimental or quasi-experimental designs with appropriate control groups to strengthen causal claims about professional development effectiveness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.L.; methodology, S.S., O.L. and A.B.; software, A.B.; formal analysis, A.B. and S.S.; investigation, O.L., S.S. and T.K.; data curation, A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B.; writing—review and editing, O.L., S.S. and T.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and publication of this article. This study was founded by the chief scientist of the ministry of education, Israel. Grant #16/6.18.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Office of the Chief Scientist, Ministry of Education, Israel (approval code: 10980, approval date: 12 November 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. Due to the sensitive nature of the data of teachers’ professional knowledge and self-efficacy, and the fact that all participants were from the same school district, the dataset is not publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Ball, D. L., Thames, M. H., & Phelps, G. (2008). Content knowledge for teaching: What makes it special? Journal of Teacher Education, 59(5), 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1986). The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 4(3), 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, P., McLaughlin, M., Bass-Gould, G., Pauly, E., & Zellman, G. L. (1977). Federal programs supporting educational change Vol. VII. Factors affecting implementation and continuation. Report No. R-1589/7-HEW. RAND Corporation. Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/reports/R1589z7.html (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Bhanji, F., Gottesman, R., de Grave, W., Steinert, Y., & Winer, L. R. (2012). The retrospective pre–post: A practical method to evaluate learning from an educational program. Academic Emergency Medicine, 19(2), 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, S., Gillis, M., Smith, T., Lavalette, M., Liss-Bronstein, L., Lowe, E., Russo, E., Silliman, E. R., & Wilder, T. D. (2009). First grade teachers’ knowledge of phonological awareness and code concepts: Examining gains from an intensive form of professional development and corresponding teacher attitudes. Reading and Writing, 22(4), 425–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirkony, C., Rickinson, M., Walsh, L., Gleeson, J., Salisbury, M., Cutler, B., Smith, K., Cripps Clark, J., & Corrigan, D. (2022). Beyond effective approaches: A rapid review response to designing professional learning. Professional Development in Education, 48(5), 777–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Learning Policy Institute. Available online: https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/teacher-prof-dev (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Darling-Hammond, L., Wei, R. C., Andree, A., Richardson, N., & Orphanos, S. (2009). Professional learning in the learning profession (p. 12). National Staff Development Council. [Google Scholar]

- Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desimone, L. M., & Pak, K. (2017). Instructional coaching as high-quality professional development. Theory into Practice, 56(1), 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desimone, L. M., Smith, T. M., & Frisvold, D. E. (2010). Survey measures of classroom instruction: Comparing student and teacher reports. Educational Policy, 24(2), 267–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, J. M., & Vaughn, S. (2009). Response to intervention: Preventing and remediating academic difficulties. Child Development Perspectives, 3(1), 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, J., Sugai, G., Simonsen, B., & Everett, S. (2009). MTSS coaching: Bridging knowing to doing. Theory Into Practice, 56(1), 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, S., & Dembo, M. H. (1984). Teacher efficacy: A construct validation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(4), 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, T. A., & DiPerna, J. C. (2007). Service delivery for response to intervention: Core components and directions for future research. School Psychology Review, 36(4), 526–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S., Harris, K. R., Fink, B., & MacArthur, C. A. (2001). Teacher efficacy in writing: A construct validation with primary grade teachers. Scientific Studies of Reading, 5(2), 177–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guskey, T. R. (1986). Staff development and the process of teacher change. Educational Researcher, 15(5), 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guskey, T. R. (1988). Teacher efficacy, self-concept, and attitudes toward the implementation of instructional innovation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 4(1), 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guskey, T. R., & Passaro, P. D. (1994). Teacher efficacy: A study of construct dimensions. American Educational Research Journal, 31(3), 627–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, R. K. (2001, January 26). Teacher self-efficacy: Substantive implications and measurement dilemmas. Keynote Address Given at the Annual Meeting of the Educational Research Exchange, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, G. S., Ralph, K. M., Gulanick, N. A., Maxwell, S. E., Nance, D. W., & Gerber, S. K. (1979). Internal invalidity in pretest-posttest self-report evaluations and a re-evaluation of retrospective pretests. Applied Psychological Measurement, 3(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M. M. (2016). How does professional development improve teaching? Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 945–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T. K., & Park, J. H. (2019). More about the basic assumptions of t-test: Normality and sample size. Korean Journal of Anesthesiology, 72(4), 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraft, M. A., Blazar, D., & Hogan, D. (2018). The effect of teacher coaching on instruction and achievement: A meta-analysis of the causal evidence. Review of Educational Research, 88(4), 547–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratochwill, T. R., Volpiansky, P., Clements, M., & Ball, C. (2007). Professional development in implementing and sustaining multitier prevention models: Implications for response to intervention. School Psychology Review, 36(4), 618–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, A., & Bradbury, O. (2024). Examining strategies to support teacher self-efficacy when working with diverse student groups: A scoping literature review. In J. Burke, M. Cacciattolo, & D. Toe (Eds.), Inclusion and social justice in teacher education (pp. 89–108). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Learning Forward. (2024). Professional learning is key to improving reading. Learning Forward Journal, 45(2), 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lipka, O. (2017). Literacy teacher efficacy scale [Unpublished measurement instrument]. University of Haifa.

- Lumley, T., Diehr, P., Emerson, S., & Chen, L. (2002). The importance of the normality assumption in large public health data sets. Annual Review of Public Health, 23(1), 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrothanasis, K., & Kladaki, M. (2025). Drama-based methodologies and teachers’ self-efficacy in reading instruction. Irish Educational Studies, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCutchen, D., Abbott, R. D., Green, L. B., Beretvas, S. N., Cox, S., Potter, N. S., Quiroga, T., & Gray, A. L. (2002). Beginning literacy: Links among teacher knowledge, teacher practice, and student learning. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 35(1), 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCutchen, D., Green, L., Abbott, R. D., & Sanders, E. A. (2009). Further evidence for teacher knowledge: Supporting struggling readers in grades three through five. Reading and Writing, 22(4), 401–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, C., Feldlaufer, H., & Eccles, J. S. (1989). Change in teacher efficacy and student self-and task-related beliefs in mathematics during the transition to junior high school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81(2), 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moats, L. C. (1994). The missing foundation in teacher education: Knowledge of the structure of spoken and written language. Annals of Dyslexia, 44(1), 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monte-Sano, C., De La Paz, S., & Felton, M. (2014). Implementing a disciplinary-literacy curriculum for US history: Learning from expert middle school teachers in diverse classrooms. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 46(4), 540–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullis, I. V. S., Martin, M. O., Foy, P., & Hooper, M. (2017). PIRLS 2016 international results in reading. Boston College, TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center. [Google Scholar]

- Mullis, I. V. S., von Davier, M., Foy, P., Fishbein, B., Reynolds, K. A., & Wry, E. (2023). PIRLS 2021 international results in reading. Boston College, TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, E. P., & Freeman, E. W. (2012). District-level considerations in supporting and sustaining RtI implementation. Psychology in the Schools, 49(3), 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2019). TALIS 2018 results (Volume I): Teachers and school leaders as lifelong learners. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, D. J. (2017). Teachers’ self-reported professional learning and the influence of school leadership and peer relationships [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Maryland.

- Piasta, S. B., Connor, C. M., Fishman, B. J., & Morrison, F. J. (2009). Teachers’ knowledge of literacy concepts, classroom practices, and student reading growth. Scientific Studies of Reading, 13(3), 224–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, M., Lambright, K., & Wijekumar, K. (2024). Professional Development in Reading Comprehension: A Meta-analysis of the Effects on Teachers and Students. Reading Research Quarterly, 59(3), 424–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J. A. (1994). The impact of an in-service to promote cooperative learning on the stability of teacher efficacy. Teaching and Teacher Education, 10(4), 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearer, B. A., Carr, D. A., & Vogt, M. (2018). Reading specialists and literacy coaches in the real world (4th ed.). Waveland Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, S., Fletcher-Wood, H., O’Mara-Eves, A., Stansfield, C., Van Herwegen, J., Cottingham, S., & Higton, J. (2021). What are the characteristics of teacher professional development that increase pupil achievement? Education Endowment Foundation. Available online: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/education-evidence/evidence-reviews/teacher-professional-development-characteristics (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Snow, C. E., Griffin, P., & Burns, M. S. (Eds.). (2005). Knowledge to support the teaching of reading: Preparing teachers for a changing world. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- TIMSS 2015 Encyclopedia. (2015). Teachers, teacher education, and professional development—Israel. TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center. Available online: http://timssandpirls.bc.edu/timss2015/encyclopedia/countries/israel/teachers-teacher-education-and-professional-development/ (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & Johnson, D. (2011). Exploring literacy teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs: Potential sources at play. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(4), 751–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & McMaster, P. (2009). Sources of self-efficacy: Four professional development formats and their relationship to self-efficacy and implementation of a new teaching strategy. The Elementary School Journal, 110(2), 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2020). 2020 GEM report—Gender report: A new generation: 25 years of efforts for gender equality in education. UNESCO Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, R. B., & Ashton, P. T. (1986). Teacher motivation and the conditions of teaching: A call for ecological reform. Journal of Thought, 21(2), 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, I., & Goddard, R. D. (2023). Professional development quality and instructional effectiveness: Testing the mediating role of teacher self-efficacy beliefs. Professional Development in Education, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ysseldyke, J. E., & McLeod, S. (2007). Using technology tools to monitor response to intervention. In S. R. Jimerson, M. K. Burns, & A. M. VanDerHeyden (Eds.), Handbook of response to intervention (pp. 396–407). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X., Shu, L., Xu, Z., & Padrón, Y. (2023). The effect of professional development on in-service STEM teachers’ self-efficacy: A meta-analysis of experimental studies. International Journal of STEM Education, 10(1), 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).