Peer Collaboration to Support Chinese Immigrant Children’s Chinese Heritage Language Use and Learning in New York

Abstract

1. Introduction and Rationale

“and it’s 上完 SAT math 课 [/] SAT math 完了之后,我们 [/] 我们就吃了 [/] 吃了一些 [纸杯蛋糕]”(“and it’s after finishing the SAT Math class [/] after the SAT math class, we [/] we ate [/] ate some [cupcakes”])

2. Research Design Overview

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Measures: Research Context and Data Collection

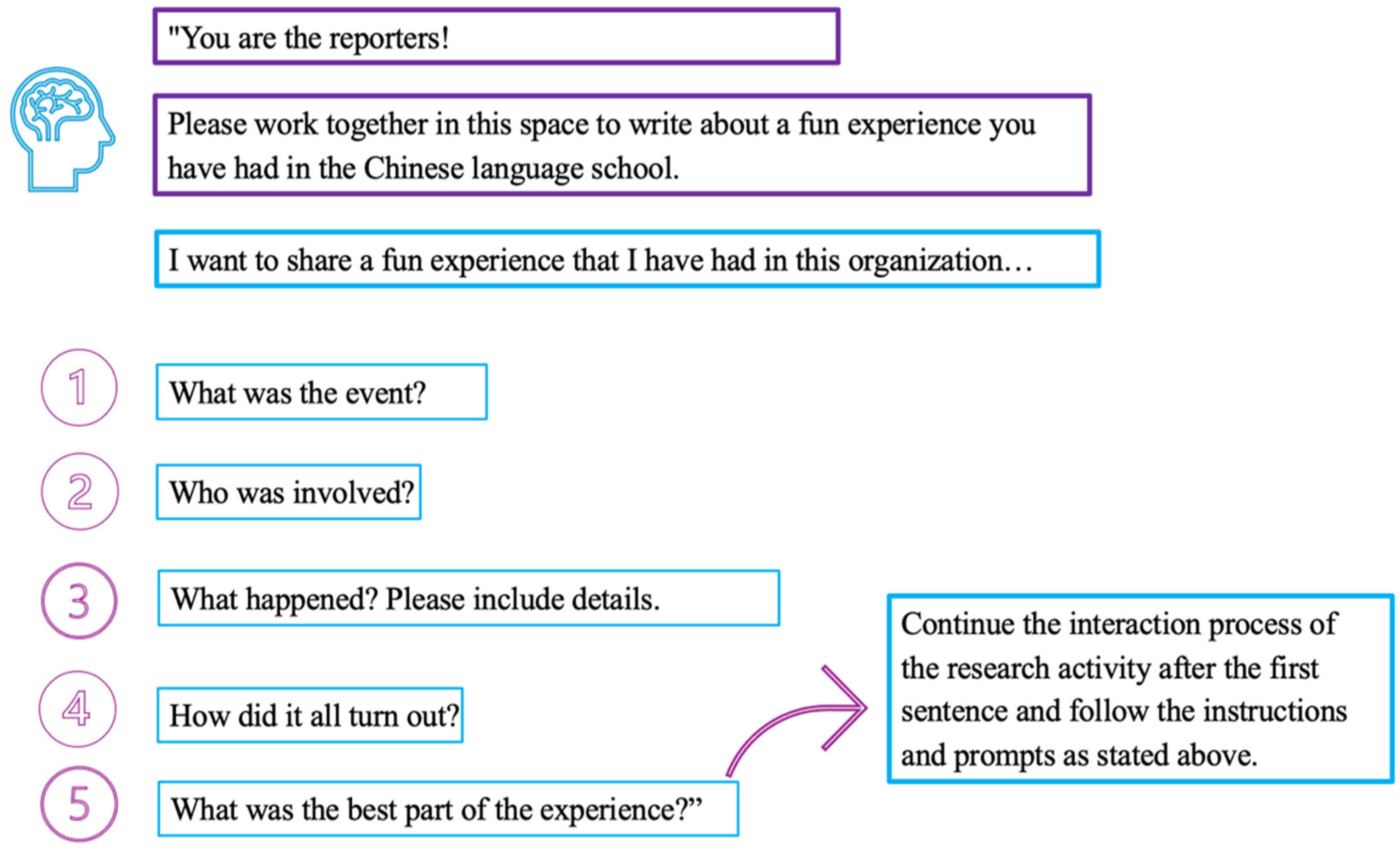

Peer Collaboration Writing Activity

3.2. Data Analysis and Interpretation Methods

3.2.1. Conversation Analysis Process and Developing of Categories

3.2.2. Plot Analysis on Children’s Final Written Letters/Narratives

3.2.3. Concept of Character Mapping Analysis on the Narrating Sections of Children’s Conversations and Final Written Letters/Narratives

- Transcribe the three verbal audio recordings of children’s peer-collaborated processes of the peer collaboration activity following the CHAT Manual (MacWhinney, 2024), and translate those conversations in Mandarin to English.

- Refer to the model of peer collaboration in practical language skill—writing acquisition (Daiute et al., 1993)—and apply in our study when applicable.

- Codings and coding process were conducted in Atlas.ti (The Student Atlas.ti 2024 Version).

- Each conversation turn was coded in Atlas.ti, by applying the categories in Daiute et al. (1993) research, as well as by starting with the data and developing new relevant conversational categories.

- Develop 38 conversational categories regarding the transcripts of the conversations of three peer groups during the peer collaboration activity.

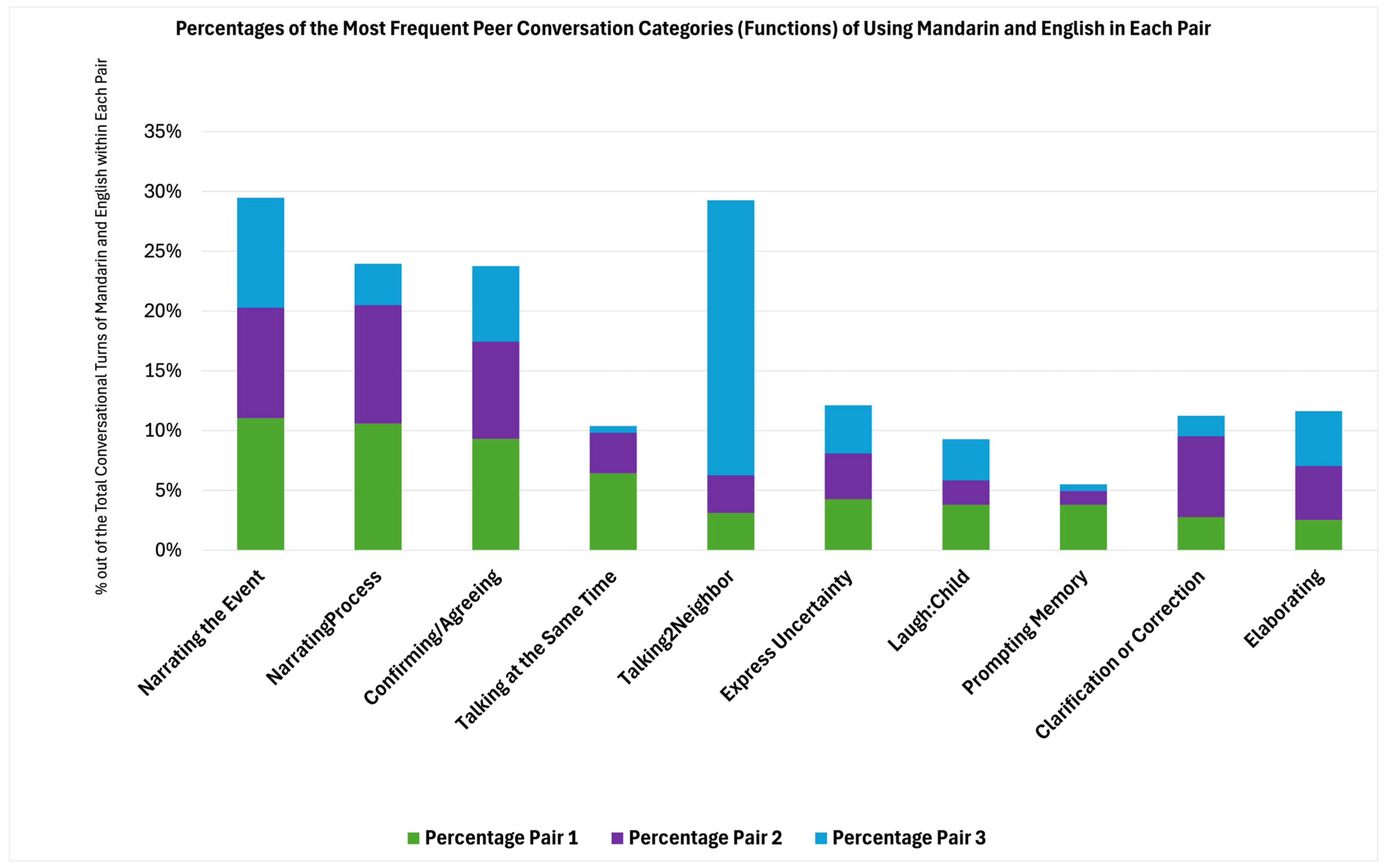

- Calculate the frequencies and percentages of some most frequently occurring conversation categories in three peer groups’ conversations, respectively, shown in Table 2. By doing so, we can capture the patterns with regard to what topics and contents children were actively talking about when they were using both English and Mandarin during the narrating process with peers.

- Apply plot analysis based on the methodology of Daiute (2014b) to analyze children’s final written letters. Use character mapping analysis on the narrating parts of children’s conversations as well as on children’s final written letters as stated in Section Character Mapping Analysis on Narrating Parts of Children’s Conversations and on Final Written Letters. Examine how children’s Chinese heritage language Mandarin was incorporated in their writing.

- Understand the connection between children’s conversations and written texts, in particular focusing on the use of Mandarin. In addition to exploring children’s uses of Mandarin and English in their conversations, this talk and text alignment examines the transfer of conversational language to written language.

4. Results

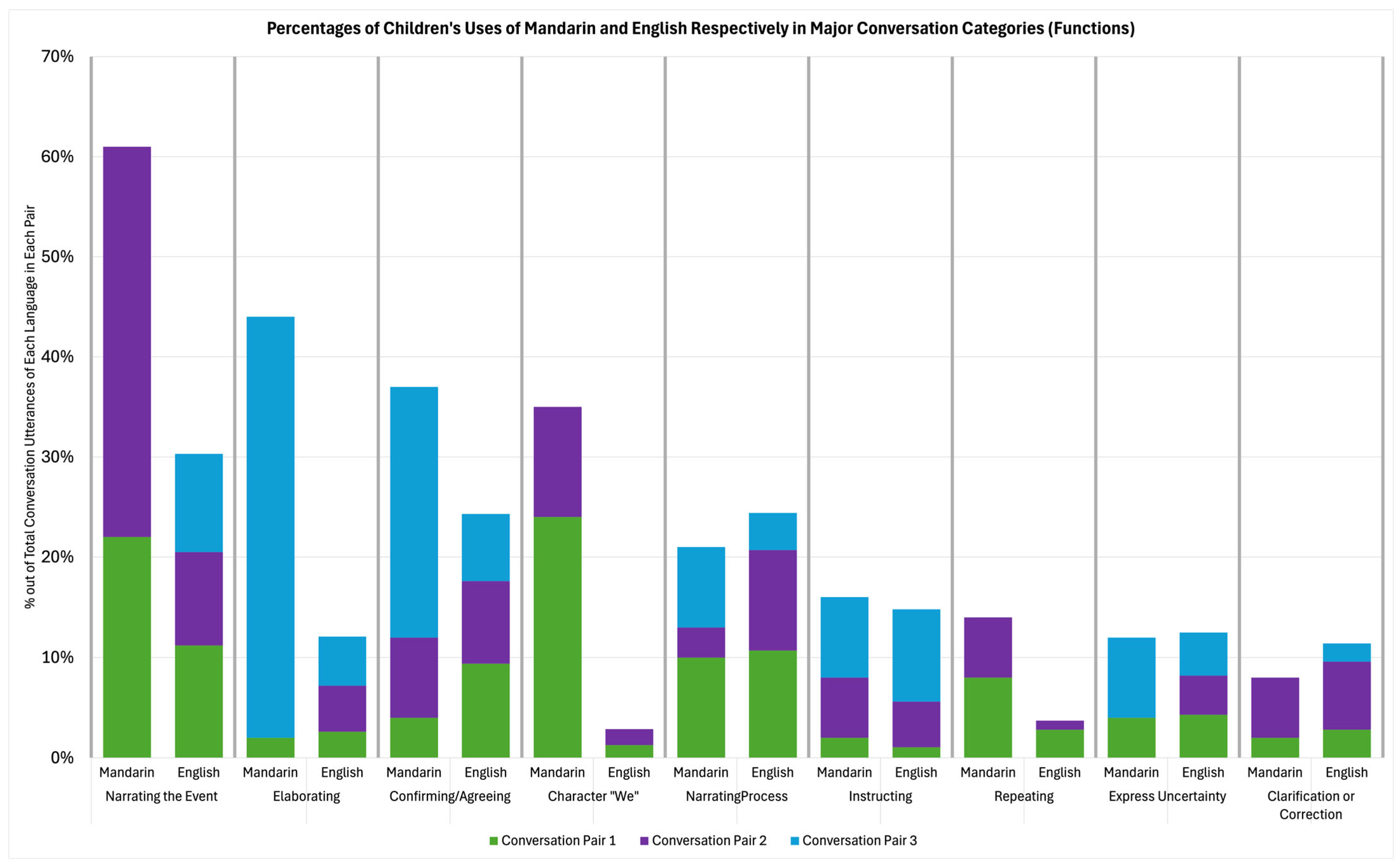

4.1. Conversation Analysis: Peers’ Functioning for English and Mandarin Uses

4.1.1. Code Groups of Peers’ Roles in Mandarin and English Uses

4.1.2. Peers’ Mandarin Uses—General Patterns and Unique Features in Each Pair

- (a)

- Mandarin Is Frequently Used When Children Are Narrating the Event, Mapping Character “We”, and During the Narrating Process

Excerpt 1:C22: Um ok, so it’s like 这是 SAT 老师给的(C2: Um ok, so it’s like these were given by my SAT teacher)C2: and it’s 上完 SAT math 课 [/] SAT math 完了之后, 我们 [/] 我们就吃了 [/] 吃了一些(C2: and it’s after the SAT Math class, we ate [/] we ate some (cupcakes))C3: 纸杯蛋糕(C3: Cupcakes)C2: (吃了)一些纸杯蛋糕(C2: We ate some cupcakes.)C1: stopC2: 还吃了一些纸杯蛋糕(C2: We also then ate some cupcakes.)

- (b)

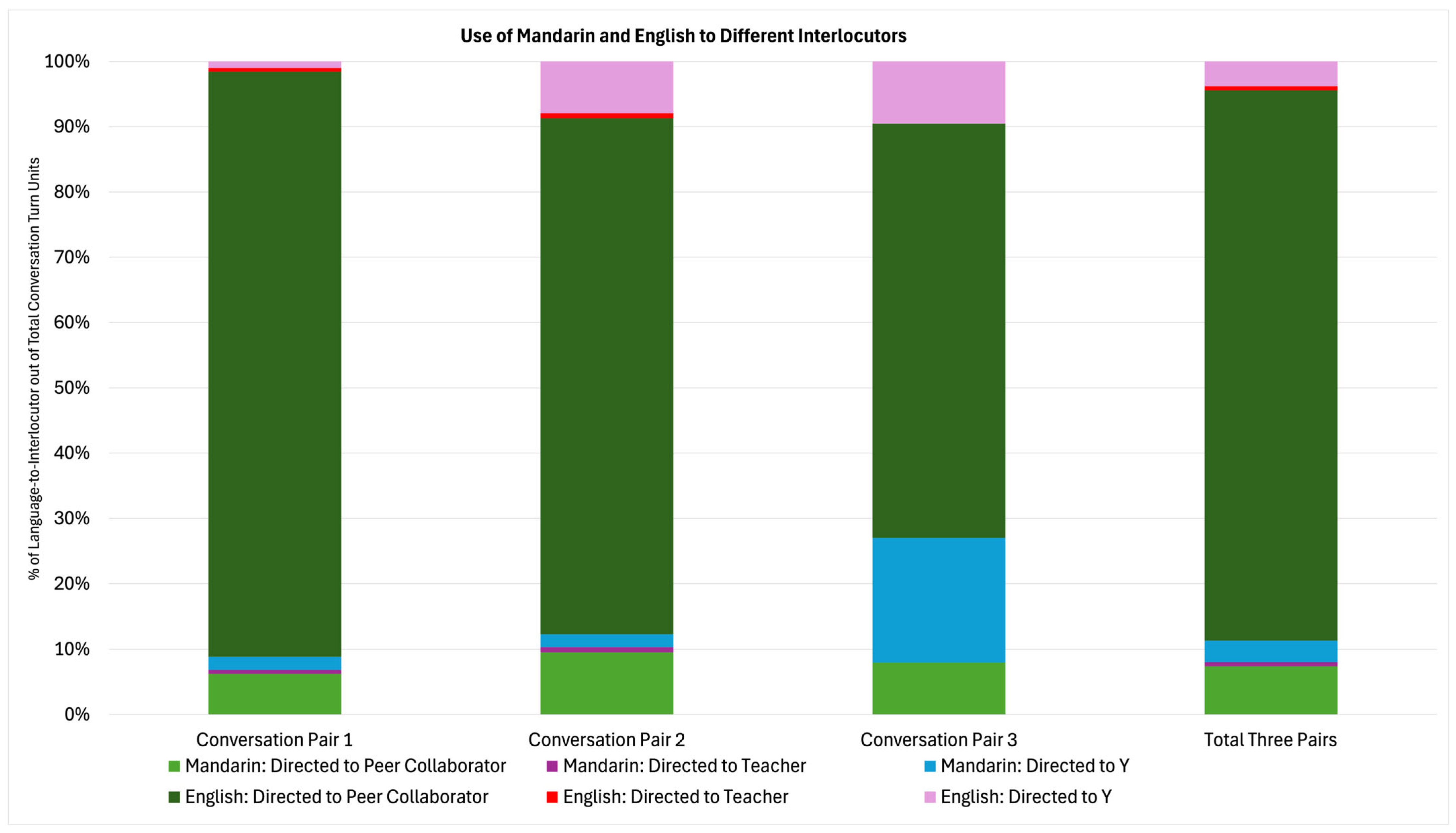

- Use of Mandarin—Conversation Turns Directed to Different Interlocutors

Excerpt 2:Zhuzhu: 老师 %com3: [calling their Chinese language teacher C], have you taught fourth grade? [/] have you taught the fourth grade?(Zhuzhu: Hi, teacher %com: [calling their Chinese language teacher C], have you taught fourth grade? [/] have you taught the fourth grade?)%com: [Zhuzhu was calling the teacher to inquire about some detail she was talking with her peer YXG about the teacher who taught them in fourth grade]⌈YXG⌉ ⌊Zhuzhu and YXG⌋: fourth gradeZhuzhu: 你教我的哥哥吗?他现在[/]在九年级(Zhuzhu: Do you teach my brother? He is [/] now at the ninth grade.)

Excerpt 3:Zhuzhu: 我们这个(.)我们需要在中文 (.)额 (.)我们需要中文写这个吗?(Zhuzhu: Our this (.) we need [to write in] Chinese (.) Em (.) Do we need to write in Chinese about this?)%com: [“this” refers to the letter produced in the peer collaboration activity]

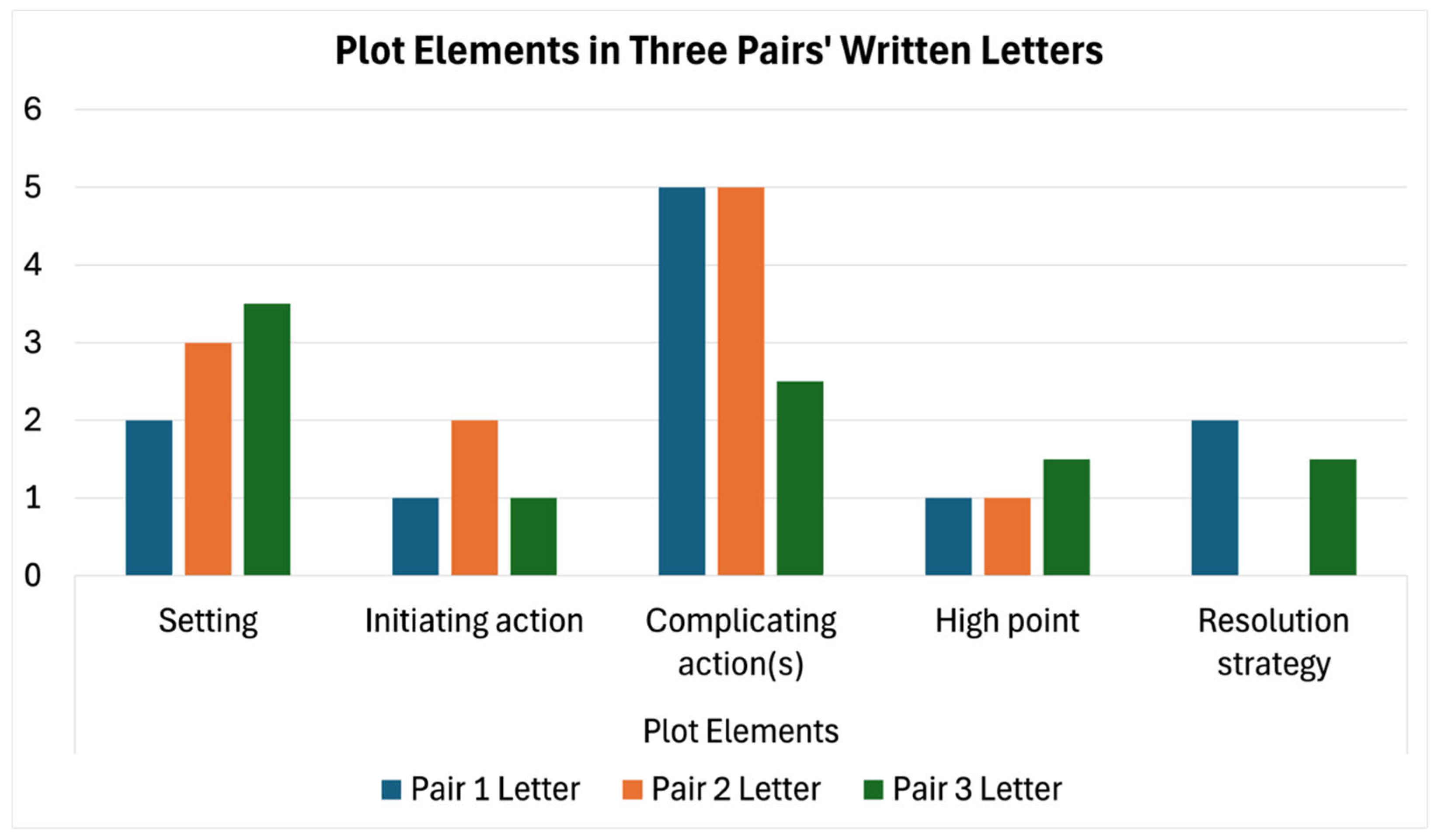

4.2. Plot Analysis on Children’s Written Letters: Mandarin Use Embedded in Plot Elements

- (1)

- Setting: Place; Background; Motivation; other set up for the story;

Example (1):“The day we met, was a day we will always remember.”“After a couple weeks of Chinese school, 我们的老师 decided to put the tables in groups.”(“After a couple weeks of Chinese school, our teacher decided to put the tables in groups.”)

- (2)

- Initiating Action: Sets the “story” in motion; where the author/speaker indicates “This is a story” (not just a description of a setting…), essay or other discourse;

Example (2):“When we walked in we were quite Chi Jing (Chinese Pinyin-Chinese phonetic alphabet) because the tables had never been like this before.”(“When we walked in, we were quite surprised because the tables had never been like this before.”)

- (3)

- Complicating Action(s): Advance the plot, that was set up in the initiating action;

Example (3):“几分钟后,其他学生来了。”(“After several minutes, other students were coming [in the classroom].”)

- (4)

- High Point/Turning Point: The point of the story, where the events/actions beginning with the initiating action integrate the author/speaker consciousness;

Example (4):“从那一刻起,我们成了好朋友。”(“From that moment of time, we became good friends.”)

- (5)

- Resolution Strategies: The plot resolves with these statements, not necessarily the real-life situation but the story, which must, after all, end (Daiute, 2014b);

Example (5):“Thus, a loved of friendship emerged, which exists to this day,”

Excerpt 4:我们四个人 seemed to hit it off right away, “using”4 papers from YXG’s notebook, writing notes to each other.(The four of us seemed to hit it off right away, “using” papers from YXG’s notebook, writing notes to each other.)

Excerpt 5:我一进中文课时,我拿了一盒纸杯蛋糕。—Setting(At the time when I entered the Chinese language class, I brought a box of cupcakes.—Setting)这是从我的 SAT 老师给的。—Setting(This was provided by my SAT teacher.—Setting)Before Chinese class, my SAT classmates ate some cupcakes and ended up not eating 5 cupcakes.—Initiating ActionThose 5 cupcakes were saved for my Chinese classmates.—Complicating Action几分钟后,其他学生来了。—Complicating Action(After several minutes, other students were coming [in the classroom].—Complicating Action)

Excerpt 6:我的爸爸 yi qian gao xu wo [Chinese Pinyin] 很多次(My dad told me for many times)

Character Mapping Analysis on Narrating Parts of Children’s Conversations and on Final Written Letters

Excerpt 7:我们都忘记了(We all forget)

Excerpt 8:YXG: When I walked in, I was very surprised. When…Zhuzhu: When (.) [/] when I (.) walked (.) in, I (.) was (.) what?[%com: writing while repeating the sentence]Zhuzhu: 吃惊,吃惊,吃惊, 吃☺ [/] 吃惊(Zhuzhu: Surprised, surprised, surprised, sur ☺ [/] surprised)YXG: ☺YXG: 吃惊(YXG: surprised)Zhuzhu: 吃惊(Zhuzhu: surprised)[%com: children were happy to verbally repeat the Chinese word together 吃惊 meaning surprised in English]Zhuzhu: 吃惊!(Zhuzhu: Surprised!)YXG: Yeah. %com: [confirming]Zhuzhu: I have to [/] I have to put in Chinese words, ok? So 吃惊(Zhuzhu: I have to [/] I have to put in Chinese words, ok? So “surprised”)

Excerpt 9:C2: 我还记得,对对对(C2: I still remember, yeah yeah yeah)%com: [talking to C1 and C3]

Excerpt 10:XXZ: I don’t think that happen because, I kinda of that some lostKZ: OhhXXZ: but I found some way back, as there was a tall buildingKZ: That’s cool!

Excerpt 11:我们五年级的第一天,我遇见了 Zhuzhu, YXG, 和 S。(The first day at our fifth grade, I met Zhuzhu, YXG, and S.)我们一起坐在一个桌子。(We sat at the same table together.)

Excerpt 12:从那一刻起,我们成了好朋友。(From that moment of time, we became good friends.)

4.3. Analyzing and Connecting Conversations with Written Letters/Narratives

4.3.1. Peer Interactions Advance the Development of Written Letters/Narratives

4.3.2. Correlation Between Conversation Categories and Plot Elements of Written Letters/Narratives

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Peer Collaboration Activity Promoting Chinese Heritage Language Learning and Education in Cultural Context

5.2. Contributions, Implications, Limitations, and Further Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The coding of the conversations was mainly conducted by the first author, but the entire coding process was conducted by both authors when applying categories from Daiute et al. (1993)’s research work, adapting categories, and creating and developing new categories in the current new context. |

| 2 | C1, C2, and C3 represent the three child participants in group 2. |

| 3 | %com was the symbol to indicate the sentence following the symbol was the researcher’s own comments, according to the chat manual of the conversation analysis when doing transcriptions of the audio-recordings of children’s conversations. |

| 4 | We corrected the words from the original written text to clarify the meaning of the sentence that children wanted to express: they were sharing the papers from YXG’s notebook to start writing notes to each other. |

| 5 | Because of the small sample size of 3 groups’ values, and our focus on probing into the in-depth peer collaboration processes and nuances, we did not conduct Chi-square analysis between the conversation categories and the plot elements categories, but focused on qualitative interpretations in the current study. |

References

- Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J. S. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Conover, K., & Daiute, C. (2017). The process of self-regulation in adolescents: A narrative approach. Journal of Adolescence, 57(1), 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daiute, C. (2014a). Character mapping and time analysis. In Narrative inquiry: A dynamic approach. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Daiute, C. (2014b). Plot analysis. In Narrative inquiry: A dynamic approach. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Daiute, C., Campbell, C. H., Griffin, T. M., Reddy, M., & Tivnan, T. (1993). Young authors’ interactions with peers and a teacher: Toward a developmentally sensitive sociocultural literacy theory. New Directions for Child Development, 1993(61), 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daussà, E. J., & Qian, Y. (2021). Language transmission among multilingual Chinese immigrant families in the northern Netherlands. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 31(2), 159–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fante, I., & Daiute, C. (2024). Pre-adolescents narrate classroom experience: Integrating socioemotional and spatiotemporal sensitivities. Narrative Inquiry, 34(1), 134–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez Parera, A. (2021). A comparison of the effects of mindful conceptual engagement for the teaching of the subjunctive to heritage- and second-language learners of Spanish. Languages, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Dobao, A. (2020). Exploring interaction between heritage and second language learners in the Spanish language classroom: Opportunities for collaborative dialogue and learning. In W. Suzuki, & N. Storch (Eds.), Languaing in language learning and teaching: A collection of empirical studies (pp. 91–110). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Fisherman, J. A. (1991). Revising language shift: Theoretical and empirical foundations of assistance to threatened languages. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- García, O., & Lin, A. M. Y. (2016). Translanguaging in bilingual education. In O. García, A. M. Y. Lin, & S. May (Eds.), Bilingual and multilingual education, encyclopedia of language and education (pp. 1–14). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, O., & Wei, L. (2015). Translanguaging, bilingualism, and bilingual education. In W. E. Wright, S. Boun, & O. García (Eds.), The handbook of bilingual and multilingual education (1st ed., pp. 223–240). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hornberger, N. (2005). Opening and filling up implementational and ideological spaces in heritage language education. Modern Language Journal, 89, 605–612. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. (2013). Interactive patterns in paired discussions between Chinese heritage and Chinese foreign language learners [Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Iowa]. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchby, I., & Wooffitt, R. (2008). Conversation analysis (2nd ed.). Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Immigration to New York. (2009). Available online: https://macaulay.cuny.edu/seminars/drabik09/articles/a/_/h/A_History_of_Chinese_Immigration_to_New_York_713b.html (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Lao, C. (2004). Parents’ attitudes toward Chinese-English bilingual education and Chinese-English use. Bilingual Research Journal, 28(1), 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney, B. (2024). Tools for analyzing talk. Part 1: The CHAT transcription format. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, C. H. (2018). Critical Language Awareness (CLA) for Spanish heritage language programs: Implementing a complete curriculum. International Multilingual Research Journal, 12(2), 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muysken, P. (2000). Bilingual speech. In A typology of code-mixing. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Muysken, P. (2013). Language contact outcomes as the result of bilingual optimization strategies. Bilingualism, 16, 709–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, H. (2024). A qualitative account of linguistic transference in a post-monolingual childhood. Asian Qualitative Inquiry Journal, 3(2), 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ol’khovskaya, A. I. (2019). Using corpus data in teaching Russian. TSPU Bulletin, 2, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otcu, B. (2010). Heritage language maintenance and cultural identity formation: The case of a Turkish Saturday school in New York City. Heritage Language Journal, 7(2), 112–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Profile of New York City’s Chinese Americans Document. (2019). One of a series of Asian American population profiles prepared by the Asian American Federation Census Information Center (CIC). Available online: https://www.aafederation.org/our-work/research/ (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Protassova, E. (2008). Teaching Russian as a heritage language in Finland. Heritage Language Journal, 6(1), 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protassova, E., & Yelenevskaya, M. (2020). Learning and teaching Russian as a pluricentric language. International Journal of Multilingual Education, 16, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, W. M., & Jornet, A. (2013). Situated cognition. WIREs Cognitive Science, 4, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, H., Schegloff, E., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organisation of turn-taking in conversation. Language, 50, 696–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sert, O., & Seedhouse, P. (2011). Introduction: Conversation analysis in applied linguistics. Novitas-ROYAL (Research on Youth and Language), 5(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Slavin, R. E. (2016). Instruction based on cooperative learning. In R. Mayer, & P. Alexander (Eds.), Handbook of research on learning and instruction (pp. 388–404). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, M. (2016). Peer collaboration in an English/Chinese bilingual program in western Canada. The Canadian Modern Language Review/La Revue Canadienne des Langues Vivantes, 72(4), 423–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, N. M., Ing, M., Burnheimer, E., Johnson, N. C., Franke, M. L., & Zimmerman, J. (2021). Is there a right way? Productive patterns of interaction during collaborative problem solving. Education Sciences, 11, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelenevskaya, M., & Protassova, E. (2021). Teaching languages in multicultural surroundings: New tendencies. Russian Journal of Linguistics, 25(2), 546–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, Y. (2012). Beyond the mother tongue: The postmonolingual condition. Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D., & Slaughter-Defoe, D. T. (2009). Language attitudes and heritage language maintenance among Chinese immigrant families in the USA. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 22(2), 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group—Child | Child Participant Pseudonym | Age of Child Participant | Gender | Number of Children in the Family; Their Age(s) | Years of Residence in The United States | Where Was the Child Participant Born | The Number of Languages Used in the Family | Language Most Frequently Used When Communicating with Child | Language Most Frequently Used When Communicating with Partner | Code-Switching and Language Mixing Phenomenon When Communicating with Child | Personal Chinese Heritage Language(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1—Child1 | Zhuzhu | 13 | Girl | 2; 15 and 13 years old | 10 | Ottawa, Canada | 2 | Mandarin, English | English | Have code-switching or language mixing, code switch between Mandarin and English | None |

| Group 1—Child2 | YXG | 11 | Girl | 2; 15 and 11 years old | 18 | New York, The United States | 2 | Mandarin, English | Mandarin | Mandarin/English | None |

| Group 2—Child1 | ND | 13 | Boy | 4; 31, 23, 19, and 13 years old | 19 | New Jersey, The United States | 2 | English | Mandarin | When communicating with children, there often exists language mixing and code-switching phenomenon; often when having difficulty in using Mandarin to communicate with children, parents will switch to English | |

| Group 2—Child2 | YQW | 12 | Boy | 2; 16 and 12 years old | 18 | New York, The United States | 3 | English | Fujian dialect (Fujianese) | English/Fujian dialect | Fujian dialect |

| Group 2—Child3 | YLW | 12 | Boy | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Group 3—Child1 | KZ | 12 | Girl | 1; 12 years old | 20 | New Jersey, The United States | 3 | Mandarin | Mandarin | Sometimes; Mandarin and English | Shanghainese |

| Group 3—Child2 | XXZ | 12 | Girl | 2; 15 and 12 years old | 12 | New York, The United States | 2 | Mandarin | Mandarin | Yes, English and Mandarin | N/A |

| Group 1 Conversation | Group 2 Conversation | Group 3 Conversation | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conversation Category | Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | Frequency |

| Narrating the Event | 96 | 11.05% | 41 | 9.23% | 16 | 9.20% | 153 |

| Narrating Process | 92 | 10.59% | 44 | 9.91% | 6 | 3.45% | 142 |

| Confirming/Agreeing | 81 | 9.32% | 36 | 8.11% | 11 | 6.32% | 128 |

| Talking at the Same Time | 56 | 6.44% | 15 | 3.38% | 1 | 0.57% | 72 |

| Child Mandarin | 42 | 4.83% | 31 | 6.98% | 12 | 6.90% | 85 |

| Talking2Neighbor | 27 | 3.11% | 14 | 3.15% | 40 | 22.99% | 81 |

| Express Uncertainty | 37 | 4.26% | 17 | 3.83% | 7 | 4.02% | 61 |

| Laugh: Child | 33 | 3.80% | 9 | 2.03% | 6 | 3.45% | 48 |

| Prompting Memory | 33 | 3.80% | 5 | 1.13% | 1 | 0.57% | 39 |

| Clarification or Correction | 24 | 2.76% | 30 | 6.76% | 3 | 1.72% | 57 |

| Elaborating | 22 | 2.53% | 20 | 4.50% | 8 | 4.60% | 50 |

| Instructing | 9 | 1.04% | 20 | 4.50% | 15 | 8.62% | 44 |

| Asking Questions | 14 | 1.61% | 19 | 4.28% | 9 | 5.17% | 42 |

| Laugh: Both/All | 12 | 1.38% | 19 | 4.28% | 5 | 2.87% | 36 |

| Pause | 24 | 2.76% | 14 | 3.15% | 7 | 4.02% | 45 |

| Evaluation Positive | 11 | 1.27% | 2 | 0.45% | 3 | 1.72% | 16 |

| Play (Taking Break, Eating, Else) | 8 | 0.92% | 12 | 2.70% | 3 | 1.72% | 23 |

| Providing Suggestions | 15 | 1.73% | 5 | 1.13% | 2 | 1.15% | 22 |

| Y 2 in Mandarin | 8 | 0.92% | 4 | 0.90% | 11 | 6.32% | 23 |

| Code Groups of Conversation Categories | Peers Conversation 1 | Peers Conversation 2 | Peers Conversation 3 | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | |

| 271 | 41.44% | 144 | 44.17% | 42 | 38.89% | 457 | 42% |

| 192 | 29.36% | 90 | 27.61% | 24 | 22.22% | 306 | 28.13% |

| 125 | 19.11% | 57 | 17.48% | 19 | 17.59% | 201 | 18.47% |

| 66 | 10.09% | 35 | 10.74 | 23 | 21.30% | 124 | 11.40% |

| Total | 654 | 326 | 108 | 1088 | ||||

| Language | Group 1 Written Letter (Frequency; %) | Group 2 Written Letter (Frequency; %) | Group 3 Written Letter (Frequency; %) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | 8 | 73% | 6 | 55% | 4 | 20% |

| Mandarin | 0 | 0% | 5 | 45% | 10 | 50% |

| Code-mixing | 3 | 27% | 0 | 0% | 6 | 30% |

| Total number of grammatical sentences | 11 | 100% | 11 | 100% | 20 1 | 100% |

| Conversation Category (Frequency) | Plot Elements (Frequency) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NE 1 | NP | CA | CM | T2N | TAST | EU | CL | EL | LC | Setting | Initiating Action | Complicating Action(s) | High Point/Turning Point | Resolution Strategy(ies) | Total Sentences | |

| Pair 1 | 96 | 92 | 81 | 42 | 27 | 56 | 37 | 24 | 22 | 33 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 11 |

| Pair 2 | 41 | 44 | 36 | 31 | 14 | 15 | 17 | 30 | 20 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 11 |

| Pair 3 | 16 | 6 | 11 | 12 | 40 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 3.5 | 1 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qian, Y.; Daiute, C. Peer Collaboration to Support Chinese Immigrant Children’s Chinese Heritage Language Use and Learning in New York. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091210

Qian Y, Daiute C. Peer Collaboration to Support Chinese Immigrant Children’s Chinese Heritage Language Use and Learning in New York. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091210

Chicago/Turabian StyleQian, Yeshan, and Colette Daiute. 2025. "Peer Collaboration to Support Chinese Immigrant Children’s Chinese Heritage Language Use and Learning in New York" Education Sciences 15, no. 9: 1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091210

APA StyleQian, Y., & Daiute, C. (2025). Peer Collaboration to Support Chinese Immigrant Children’s Chinese Heritage Language Use and Learning in New York. Education Sciences, 15(9), 1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091210