2. Literature Review

English language education in Japanese schools is dictated by the federal government, to prepare students for university entrance exams through the dual foci on grammar and reading (

Paxton et al., 2022). At the tertiary level, many English language programmes incorporate listening and speaking skills, along with regular tests. While many studies in Japan focus on learners’ English acquisition through TOEIC scores, there is limited research on intercultural competence and its impact on language improvement to enable effective communication in diverse cultural settings.

Deardorff (

2020) highlights the importance of both formal and informal learning for developing ICC. As a supplement to traditional class instruction, informal learning ‘occurs through daily lived experience in interacting with those who differ in age, gender, religion, ethnicity and socio-economic status’ (

Deardorff, 2020, p. 6). Informal learning experiences are largely underutilised and under-researched in English university programmes.

The Japanese education system implements English via the grammar-translation method (訳読:

yakudoku in Japanese, meaning

translation) which teaches students how to read a text and translate it into Japanese (

Gorsuch, 1997;

Saitō, 2015;

Hino, 1988;

Igarashi, 2022). This practice teaches reading and grammar skills which are helpful for test-taking, but not necessarily transferable to spoken interactions (

Igarashi, 2022). Unfortunately, Japanese students’ English levels have been declining for decades. A recent survey places the national English proficiency at a record low of 92 out of 116 non-English speaking countries (

Saito, 2024), coinciding with research that found English language a demotivator among Japanese school students (

Kamino & Hooper, 2024;

Hooper, 2020;

Hosaka, 2020;

Pinner, 2016). Therefore, English education in Japan may need to change its approach to enhance speaking skills. One way could be through direct dialogue with culturally diverse interlocutors, a form of authentic interaction

Roever and Dai (

2021) refer to as ‘interactional competence’:

Understanding of the interlocutor involves real-time decoding of incoming language… To be able to respond, interlocutors must understand the content of what is being said, but to be able to respond appropriately they must also understand what action is being done and how the utterance frames the relationship between the interactants. All of this happens before the interlocutor has even finished speaking.

(p. 26)

Interactional competence, the ability to respond in the moment, is related to ICC, which involves cultural knowledge and language ability. Both skills are speaking-based. However, Japanese students often lack speaking experience and skills due to a focus on grammar and reading in their English education.

Takeshita (

2016) explains that opportunities to engage with culturally diverse interlocutors are rare in Japan, where daily communication typically occurs in the mother tongue. Despite six years of compulsory English education, many Japanese students demonstrate limited speaking skills (

Inuzuka, 2017), and classroom practices often fail to foster ICC (

Hanada, 2019). This is particularly concerning given

Deardorff’s (

2004) definition of ICC—mentioned earlier—as the ability to communicate effectively and appropriately in intercultural situations based on one’s intercultural knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Although widely accepted in global education discourse, this conceptualisation has had limited influence on mainstream English pedagogy in Japan, which continues to prioritise grammatical accuracy over authentic intercultural engagement. English education has been emphasised to improve international communication, yet there remains an absence of specific goals and measurable objectives for assessing these skills (

Fritz & Murao, 2020). These conditions highlight the need for educational reform that aligns language instruction with the development of ICC through meaningful, real-world interaction. Implementing intercultural content, non-native speaking skills, and interactions with diverse interlocutors are essential. This study aims to identify factors that facilitate culturally diverse interactions domestically and abroad to enhance ICC.

Intercultural communicative competence (ICC) has been researched by

Kim (

1991),

Wiseman (

2002), and

Byram (

2012), among others. It has been measured through various models, including the Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (

Bennett, 1986), the Intercultural Sensitivity Scale (ISS) (

Chen & Starosta, 2000), and the Intercultural Development Inventory (

Hammer, 2009). Chen and Starosta’s ISS model, in particular, has been widely adapted across countries and contexts beyond its original design.

Despite this global uptake, the use of the Intercultural Sensitivity Scale (ISS) within Japanese universities remains limited. A systematic review of 325 studies on intercultural competence in higher education (

Guillén-Yparrea & Ramírez-Montoya, 2023) confirms the ISS as a commonly employed tool but highlights a lack of region-specific research in East Asia. While studies such as

Tarchi et al. (

2019) demonstrate the ISS’s integration with qualitative methods in European contexts, similar methodological applications are scarce in Japan. Although national initiatives like the MIRAI Program—launched in 2015 to promote mutual understanding and academic exchange between Japan and Europe—underscore Japan’s institutional commitment to intercultural development, empirical studies employing the ISS in Japanese university settings are notably underrepresented in the literature (

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 2015). This gap suggests a need for further localized research to evaluate the scale’s relevance and effectiveness in Japanese higher education.

This need is further supported by Chen and Starosta’s own assertions that true understanding of cultural differences arises through direct or indirect interactions, rather than through textbooks or other static resources. While classroom learning plays a role, ICC is most effectively developed through authentic dialogue and engagement. Furthermore,

Chen and Starosta (

2008) emphasize that competence involves adopting others’ perspectives—something only accessible through real-world intercultural experiences.

However, the models commonly used to assess ICC, including the ISS, may not fully capture the sociocultural nuances of the Japanese context. These frameworks, developed in Western settings, often emphasize individual expression, direct communication, and assertiveness—traits that may not align with Japanese cultural norms that prioritize harmony, indirectness, and group orientation. To address these limitations, the current study adopts a multimodal approach incorporating both a reflective journal and a semi-structured interview. This design enables participants to articulate their intercultural learning journey in their own terms, offering insights that are both personally meaningful and contextually relevant. By allowing for narrative depth and participant agency, this approach enhances the cultural sensitivity of the research tools and supports a more nuanced understanding of ICC development within Japanese higher education.

A learner’s change through such experiences is referred to as transformational learning (

Mezirow, 1990,

1995,

1996,

1997;

Cranton, 1994,

1996).

Mezirow (

1997) defines transformational learning as a frame of reference composed of habits of mind and a point of view. Reflective practices are necessary for second-language learners to identify their thought patterns and perspectives to enhance learning experiences. The goal is autonomous thinking, achieved through critical reflection on assumptions underlying interpretations and beliefs.

Mezirow (

1997) argues this involves setting learning objectives to gauge progress and develop the skills needed for critical reflection and effective discourse. Transformative learning is applicable to study abroad as it provides cultural experiences that challenge preconceived notions. Reflective tasks help learners process these challenges, identify new understandings, and develop effective communication skills in the new environment.

While transformational learning theory provides a framework for understanding how learners critically reflect on and reshape their perspectives, acculturation theory offers a complementary lens for examining how these shifts unfold in intercultural contexts. Acculturation, broadly defined as the process of cultural and psychological change resulting from intercultural contact (

Berry, 1997), offers a useful lens for examining student experiences in study abroad contexts. While acclimatisation refers more narrowly to physical or behavioural adjustment, acculturation encompasses deeper shifts in communicative style shaped by sustained intercultural exposure. In this study, the concept is particularly relevant to the participant’s 14-week study abroad experience in Sydney, where both classroom learning and homestay interactions created opportunities for intercultural adaptation. Later findings illustrate how these experiences contributed to a noticeable change in the participant’s communicative style, reflecting the dynamic nature of acculturative learning in immersive environments.

Building on

Berry’s (

1997) conceptualisation of acculturation, recent empirical studies conducted in Australia provide further insight into how international students adapt and develop intercultural competence through language use and peer interaction. Acculturation among international students in Australia has been closely linked to both linguistic proficiency and intercultural engagement.

Jee (

2025), in a study of South Korean immigrants, found that English proficiency was the strongest predictor of sociocultural adaptation, accounting for over half the variance in adjustment outcomes. Similarly,

D’Orazzi and Marangell (

2025), in research conducted at one international university in Australia, highlight the importance of learning and communicating with culturally diverse peers as a pathway to intercultural competence. Their findings also advocate for curricula that move beyond Western-centric frameworks, exposing students to a broader range of cultural beliefs and practices. These factors are considered in the present study, particularly for participants who undertook study abroad programs in Australia, where both language use and intercultural interaction were central to their developmental experiences.

These findings underscore the importance of immersive and socially embedded learning environments, which often present learners with unfamiliar cultural norms and communicative practices. Such conditions can act as catalysts for transformational learning, particularly when they involve reflective engagement with intercultural dilemmas. In study abroad contexts, these challenges often emerge through homestay interactions, classroom discourse, and peer relationships, prompting learners to reassess assumptions and develop new communicative strategies.

Crane and Sosulski (

2020) explain that transformational learning is facilitated by a dilemma that causes uncomfortable destabilisation, similar to the experience of studying abroad. In new surroundings, Crane and Sosulski expound, “learners must expand their capacity to imagine others’ perspectives and habits of mind, rather than continuing to rely upon their own (often assimilated and unconscious) perspective when attempting to make sense of new information” (p. 71). This process can be facilitated through reflective writing, as will be demonstrated in the current project, showcasing transformative learning in a case participant. Specifically, the sojourn led to a shift in the learner’s perception from being a “language learner” to a “language user” (

Deacon & Miles, 2023, p. 262), and positioned them towards the host target language and culture (

Crane & Sosulski, 2020;

Crane, 2018;

Johnson, 2015;

Johnson & Mullins Nelson, 2010). In summary, studying abroad can significantly enhance a learner’s ability to adopt new perspectives and integrate into a different cultural and linguistic environment, thereby fostering the development of ICC.

3. Materials and Methodology

The project demonstrated ICC development through a comprehensive methodological framework that integrated multiple research tools and an analytical approach. While the theoretical foundations and key models informing this study have been outlined in the literature review, it is worth reiterating that the framework is situated within an interpretivist paradigm, which prioritises learners’ subjective experiences and meaning-making processes. The study builds on established ICC models (e.g.,

Chen & Starosta, 2000;

Bennett, 1986) and responds to critiques of their limited cultural adaptability in Japanese contexts. Although the Intercultural Sensitivity Scale (ISS) has seen widespread global use, its application in Japanese higher education remains underexplored (

Guillén-Yparrea & Ramírez-Montoya, 2023). This study addresses that gap by integrating the ISS with qualitative tools—reflective journals and interviews—to capture the sociocultural nuances of ICC development.

To track ICC growth throughout an English-major BA degree, the research questions were designed to elicit information on participants’ ongoing language skills, intercultural knowledge, and experiences. Data were collected over a two-year period using a survey, a journal, and interviews. As part of the programme, the participant completed a 14-week study abroad in Sydney, Australia, following a pre-departure orientation class at the home university. He travelled with a group of Japanese students from the same institution and was enrolled in general English classes during the week. Weekends were spent with a host family, offering potential opportunities for informal interaction in a different cultural setting. In this study, “study abroad” refers specifically to the structured 14-week homestay and English language programme at the host institution. The term “sojourn” is used more broadly to encompass the participant’s entire time in Australia, including both formal learning and daily intercultural interactions.

The framework guided the collection and interpretation of data, with interview questions specifically probing students’ intercultural backgrounds, awareness of non-Japanese cultures, and involvement in activities in and beyond the classroom. Narrative Analysis was incorporated to interpret individual learner stories and gain deeper insights into their linguistic and intercultural development. This analytical approach provided a nuanced understanding of how ICC evolves in the Japanese university context.

This paper is part of a two-year longitudinal study on 11 Japanese university students (10 female, 1 male) majoring in English. The programme includes coursework in English language and cultural understanding, along with a study abroad pre-departure orientation. Using a mixed-method approach, the study aimed to identify factors contributing to ICC development through multimodal tools: a survey (Intercultural Sensitivity Scale), a journal (

Hyers, 2018), an interview (

Brinkmann & Kvale, 2005;

Duncombe & Jessop, 2002), and TOEIC test scores (

Hsieh, 2023). While the ISS has been used in prior ICC research, this study adds triangulation and longitudinal analysis. It also incorporates communicative elements in journal-reported critical incidents. The selected case study participant shows clear growth in language and cultural understanding, reflecting ICC development.

In line with ethical research practices, participants were recruited from the first-year university cohort on a voluntary basis. In accordance with the ethical guidelines of both the researcher’s home institution and the host university in Japan, all participants signed informed consent forms prior to participation. They were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. To acknowledge their time and contribution, participants received compensation for each of the three data collection phases in which they participated.

Each data collection session lasted approximately 1.5 h and included completion of a survey, submission of a weekly journal entry, a semi-structured interview, and TOEIC scores. To ensure accessibility and comprehension, all research instruments were translated into Japanese. Participant responses, including interview transcripts and journal entries, were subsequently translated from Japanese into English. As a fluent Japanese speaker, the researcher conducted the translations, which were then reviewed by a native Japanese speaker to ensure accuracy and consistency, thereby supporting the reliability of the data.

To further ensure ethical integrity, the researcher did not hold any teaching responsibilities for the students involved in the study, thereby minimizing potential power imbalances or conflicts of interest.

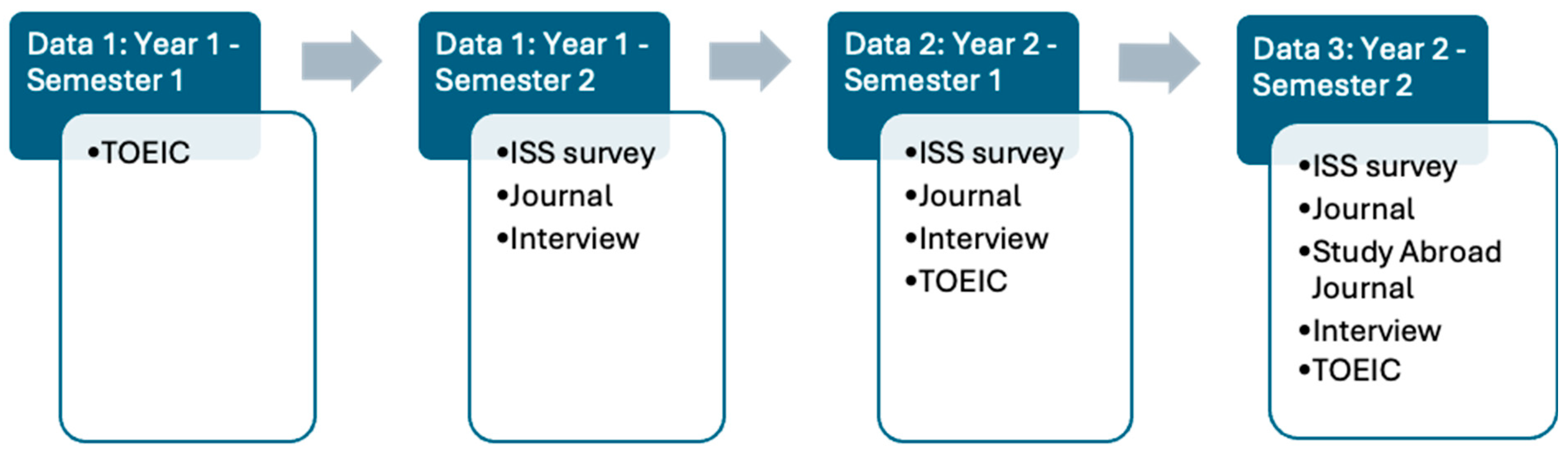

Participants completed three rounds of data collection from 2023 to 2024 (see

Figure 1): Data 1 was taken in their first year, second semester; Data 2 second year, first semester; and Data 3 second year, second semester post-study abroad. Data were collected from responses to the ISS and journal via an app, and a one-hour semi-structured Zoom interview, approximately three hours total. Students also provided English TOEIC test scores, part of their BA requirements.

The project was designed to identify ICC-related concepts across the dataset by linking all research tools. Central to the design is the Intercultural Sensitivity Scale (ISS) survey (

Chen & Starosta, 2000), which measures ICC through five categories: Interactional Engagement, Enjoyment, Confidence, Attentiveness, and Respect for Cultural Differences. While all five categories were considered, only Interactional Engagement, Enjoyment, and Confidence were consistently reflected in the journal and interview data. These three categories were therefore selected for focused analysis, as they provided the most reliable points of triangulation across the multimodal dataset. The ISS includes 24 items rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree), which were translated into Japanese. Scores for each category were calculated and compared across three data collection phases to track participants’ progress or regression in ICC development.

In addition to ISS survey responses, data were collected from a weekly journal in which students described their activities in non-Japanese languages, primarily English. These activities spanned classroom learning, social interactions, and entertainment. Journal writing facilitated critical reflection, supporting the analytical framework previously outlined. Prompts such as ‘What did I learn? What worked well, and what could be improved?’ (

Mezirow, 1990, p. 9) encouraged participants to critically examine their assumptions and learning processes. Entries were analysed as critical incidents (

Tripp, 2012), often revealing moments of discomfort and destabilisation consistent with the dilemmas described by

Crane and Sosulski (

2020). These reflections provided insight into participants’ evolving frames of reference, as conceptualised by

Mezirow (

1997), and helped illuminate the processes of transformation within intercultural learning contexts.

Building on these insights, semi-structured interviews were conducted in Japanese to explore how participants’ experiences aligned with ISS categories. Students discussed their English language education, cultural experiences, and views on learning in and outside the classwork. To deepen understanding and elaborate on earlier responses, participants’ survey data and journal entries were reviewed and discussed during the interviews conducted across three data collection phases. Transcripts were translated into English, coded by ISS category, and analysed.

Dataset responses were analysed using Narrative Analysis, a method that views individuals as meaning-makers who use stories to interpret and communicate their experiences (

Smith & Monforte, 2020).

Riessman (

2008) emphasises the importance of allowing participants’ narratives to shape the analysis. This approach aimed to explore how students engaged with non-Japanese resources during university, using triangulated data to construct their stories. Narrative Analysis thus revealed the development of participants’ English and intercultural competence during the project.

Within this integrated framework, TOEIC scores were used as quantitative indicators of linguistic proficiency and tracked across three data collection phases. While not designed to measure intercultural competence directly, these scores provided a useful reference point for examining broader developmental trends. ISS scores offered a complementary quantitative measure, capturing shifts in intercultural sensitivity over time. Together, these tools allowed for a dual lens on Ken’s progress—linguistic and intercultural—across the study period.

To deepen this analysis, TOEIC and ISS scores were interpreted alongside qualitative data from journal entries and interviews. Increases in TOEIC scores were considered in relation to the frequency and complexity of Ken’s language use, as recorded in journal activity logs, and the depth of reflection evident in critical incidents and interview responses. This triangulated approach enabled a more nuanced understanding of Ken’s development, suggesting that linguistic gains may have supported or coincided with increased intercultural awareness and sensitivity.

An integrated analysis of interviews, journals, ISS scores, and TOEIC results were triangulated to trace learners’ development in English and cultural understanding. This progression was shaped by university materials, apps, and interactions with diverse counterparts. One participant was selected for detailed analysis based on their study profile, outlined below. The dataset maps undergraduate ICC development along a continuum.

5. Findings

The findings trace a learner’s development and highlight practices that support ICC, offering insights to enhance language assessments and English interaction. Notably, development occurred primarily outside university classes—particularly in Ken’s international workplace and during study abroad. TOEIC scores, testing English listening and reading skills, complement the dataset, providing a broader view of language proficiency and potential contributions to ICC and second-language programme design. Data were analysed using three of the five ISS survey categories: Interaction Engagement, Interaction Enjoyment, and Interaction Confidence. These categories were selected based on relevance and evidence in the data, while Interaction Attentiveness and Respect for Cultural Differences were excluded, as participants did not associate them with their learning experiences. Ken’s responses across the ISS survey, journal entries, and interviews were categorised accordingly, with TOEIC scores included to illustrate communicative improvement and potential links to ICC development.

The ISS categories are defined following

Chen and Starosta (

2000), with responses rated on a five-point Likert scale. Engagement reflects openness and responsiveness to cultural differences; Enjoyment captures emotional responses to intercultural interactions; and Confidence relates to sociability and communicative assurance. These scores were triangulated with qualitative data from interviews, journals and TOEIC results. TOEIC scores, measuring listening and reading skills, were recorded across the study, with improvements noted.

Participants completed journal entries structured in two parts: (1) a table logging English-related activities (e.g., classwork, conversations, entertainment), and (2) responses to reflective prompts on linguistic or cultural encounters that were memorable or challenging. These prompts were designed to elicit critical reflection, in line with

Chen and Starosta’s (

2008) emphasis on experiential learning and perspective-taking. The journal served both as a data source and a reflective tool, enabling participants to document and interpret their intercultural experiences over time.

Ken’s journal entries were analysed in two ways: activity logs were examined for frequency and English language use across contexts, while reflective responses were compiled into critical incidents, all of which occurred in his international workplace. Interview data were deductively coded using items within each category of the Intercultural Sensitivity Scale (ISS), aligning qualitative reflections with the quantitative framework. ISS scores and TOEIC results were treated as standalone indicators of progress across three data collection phases.

The following section presents Ken’s interview excerpts, ISS scores, journal entries, and TOEIC results, analysed by phase and interpreted through the lens of the ISS model.

These findings are consistent with prior research on study abroad and ICC development in ESL/EFL contexts. Studies such as

Benson et al. (

2013) and

Fujio (

2018) have shown that immersive experiences contribute significantly to learners’ communicative competence, even when improvements in test scores are modest. Ken’s case supports this by demonstrating how sustained intercultural contact, reflective practice, and real-time interaction fostered a shift toward communicative clarity and confidence. His development also aligns with

Deardorff’s (

2020) emphasis on integrating formal and informal learning to support ICC, and

Roever and Dai’s (

2021) framing of interactional competence as central to effective communication. By documenting Ken’s trajectory across structured instruction, workplace interaction, and study abroad, this study reinforces the view that ICC is best cultivated through context-rich, socially embedded experiences rather than through language instruction alone.

The first data collection phase, conducted in year one, semester two, reveals early signs of Ken’s intercultural development. These scores were derived using the Intercultural Sensitivity Scale (ISS), administered during each phase to measure Engagement (range: 0–31), Enjoyment (range: 0–15), and Confidence (range: 0–21). As outlined in the methodology, scores were calculated by summing item responses within each category, with higher scores indicating greater intercultural sensitivity in that domain.

Ken’s high Engagement score (26/31) aligns with his leadership role in a culturally diverse school, suggesting that prior exposure to multicultural environments fostered a positive orientation toward intercultural interaction. This supports

Mezirow’s (

1997) notion that disorienting dilemmas—such as navigating leadership in a multilingual team—can catalyse perspective transformation. Ken’s description of the experience as an “international meet” reflects an emerging intercultural mindset, where diversity is framed as opportunity rather than challenge:

Excerpt 1: I was one leader, another was Russian, Romanian and Chinese *laughs. It felt like an international meet, the Olympics. I thought of it as an international exchange and started studying English from then.

Ken’s Enjoyment score (7/15), while moderate, is contextualized by his limited linguistic proficiency at the time. His fond recollection of the experience suggests that emotional positivity can coexist with communicative struggle, reinforcing the idea that affective engagement is not solely dependent on language mastery:

In contrast, Ken’s mid-range Confidence score (16/21) and his decision not to study abroad highlight a gap between willingness and perceived ability. His hesitation reflects a common dilemma among Japanese learners: the tension between aspiration and self-efficacy in intercultural contexts:

Despite this hesitation, Ken’s workplace offered an alternative site for intercultural engagement. The café, located in central Tokyo, employed staff from various countries and served customers visiting Japan for work or holiday. English was the primary language of communication, and Ken regularly interacted with both colleagues and clientele from diverse cultural backgrounds. These conditions created frequent opportunities for intercultural communication and language use, making the workplace a key site for ICC development. His reflections on communication in this setting reveal both growth and ongoing challenges.

Such moments of self-doubt are critical in transformational learning, as they prompt reflection and potential re-evaluation of one’s communicative identity. Ken’s journal entry further illustrates this internal conflict. His inability to express himself and understand others led to a resolution to “not panic,” indicating a shift from helplessness to strategic self-regulation:

This moment can be interpreted as a micro-level transformation—an adaptive response to intercultural stress that signals the beginning of deeper competence development. His initial TOEIC score of 375 provides a baseline for tracking linguistic growth, but more importantly, it contextualizes his early struggles and frames subsequent progress as both linguistic and psychological.

In Ken’s second year at university, his continued employment in an international workplace appears to reinforce and deepen his intercultural competence. His Engagement remains high, as reflected in his proactive approach to resolving language-related challenges. Seeking support from a university teacher for workplace communication issues demonstrates initiative and resourcefulness—key indicators of intercultural Engagement:

Excerpt 6:

Interviewer: You said in the previous interview you asked English questions to a university teacher about foreign customers.

Interviewee: I went to ask a teacher. They were English questions, they were difficult.

This excerpt suggests that Ken is not only encountering real-world intercultural dilemmas but is actively seeking solutions. Such behaviour aligns with the

Crane and Sosulski (

2020) concept of workplace dilemmas as catalysts for reflection and transformation. His Engagement score (24/31) remains strong, indicating sustained openness and responsiveness to intercultural challenges.

Ken’s Confidence shows marked improvement, rising from 16 to 20 out of 21. This is supported by his reflection on enhanced listening and pronunciation skills:

This excerpt reflects a shift from passive comprehension to active participation, suggesting a growing sense of communicative assurance. The increase in Confidence may be attributed to both his academic engagement and sustained workplace exposure, reinforcing the idea that ICC development is multimodal and context-dependent.

Ken’s Enjoyment score (5/15) remains modest, yet his journal and interview data reveal moments of genuine pleasure in intercultural interaction:

This statement reflects affective engagement and a positive emotional response to intercultural communication, even if not fully captured by the ISS metric. It suggests that Enjoyment, while numerically low, may be situational and episodic—surfacing in specific interactions rather than as a generalised disposition.

Ken’s second critical incident, involving customer interaction, demonstrates both Engagement and Enjoyment. His initiative to learn from these encounters and his description of them as “fun” indicate a shift from anxiety to appreciation. This aligns with

Mezirow’s (

1997) theory of transformational learning, where repeated exposure and reflection lead to a redefinition of self in relation to others.

His TOEIC score increase of 160 points (from 375 to 535) further supports the interpretation of linguistic and intercultural growth. While TOEIC measures receptive skills, the improvement suggests that Ken’s communicative confidence is grounded in measurable progress, reinforcing the link between language development and ICC.

Ken’s developmental trajectory shows a shift from tentative engagement to strategic participation. In Phase 1, intercultural exposure sparked motivation but was tempered by linguistic limitations and self-doubt. By Phase 2, Ken demonstrates increased agency—seeking academic support, identifying linguistic gains, and expressing enjoyment in intercultural exchanges. His Confidence growth and TOEIC improvement suggest that multimodal learning (academic + workplace) fosters both linguistic and intercultural competence. These findings align with

Mezirow’s (

1997) theory of transformation through reflection and

Crane and Sosulski’s (

2020) framing of workplace dilemmas as developmental catalysts.

This trajectory also reflects patterns observed in prior research on study abroad and communicative competence in ESL/EFL contexts. For example,

Benson et al. (

2013) highlight the role of daily language use in shaping learner identity and competence, while

Fujio (

2018) notes that ICC gains often exceed linguistic improvements in formal assessments. Ken’s TOEIC score increase and growing Confidence support this distinction. His case also reinforces

Deardorff’s (

2020) call for integrating formal and informal learning, and

Roever and Dai’s (

2021) emphasis on interactional competence as a key outcome of real-world language use.

Ken’s third dataset, collected after his study abroad experience in Australia, reveals a significant transformation in his intercultural competence. His Engagement score peaks at 27/31, the highest across all phases, reflecting increased openness and initiative. This is exemplified by his decision to take an optional cultural class:

This excerpt marks a shift toward direct communication, a departure from the ambiguity often associated with Japanese interaction styles. Ken’s reflection aligns with

Mezirow’s (

1990) notion of a non-reversible shift toward greater openness and communicative clarity.

Ken’s Confidence reaches the maximum score of 21/21, supported by his observations of his host brother’s assuredness:

Excerpt 10: …he had strong confidence in himself, pride. So, if he decided to do something, he would continue doing it till it was done… He had a strong sense of self.

This comparison prompts Ken to reflect on his own communicative identity, suggesting a deeper internalisation of intercultural norms. His Enjoyment score remains consistent (7/15), which may reflect the dual nature of sojourn experiences—both challenging and rewarding.

Ken’s final critical incident illustrates his transformation from linguistic anxiety to confident self-expression:

This contrasts sharply with his first-year journal entry, where he panicked during workplace communication. His joy at being recognised for his accent reflects both linguistic progress and cultural integration.

Ken’s journal entries from Australia further support this transformation. Early entries show low Confidence (“I should have studied more English”), while mid-sojourn reflections reveal signs of acculturation, as Ken began adapting to the cultural and communicative norms of his host environment (“I got used to life in Australia”). Engagement is evident in his proactive communication with his host family, and Enjoyment emerges in his final reflection: “I enjoyed everything about study abroad”.

Ken’s transformation during study abroad reflects findings from previous research on ICC development in immersive environments.

Fujio (

2018) and

Benson et al. (

2013) emphasise that while linguistic gains may be modest, intercultural competence often develops significantly through daily interaction and cultural adaptation. Ken’s increased Confidence and shift toward direct communication support this view. His experience also aligns with

Deardorff’s (

2020) argument that ICC is best cultivated through a blend of formal instruction and informal, experiential learning. The recognition of his accent and his comfort in intercultural exchanges further illustrate the development of interactional competence, as described by

Roever and Dai (

2021), reinforcing the value of real-world communicative practice in ESL/EFL contexts.

A pivotal moment is captured in his post-sojourn interview:

Excerpt 12: …my host brother did weight training and this day I’d walked quite a lot around Sydney, and I was tired, I came home tired. Then he said: ‘(name), let’s train!’ In Japan I would have said ‘Yeah, ok’ and instead I told my host brother: ‘No’ *laughs. This is a huge example for me. I wondered if it would be better to be as direct as possible, without getting caught up in my lack of English.

This moment encapsulates Ken’s shift from prioritising linguistic accuracy to valuing communicative clarity. His laughter signals retrospective Enjoyment, while his assertiveness reflects Confidence and Engagement. This change in communicative style illustrates acculturative learning, where sustained intercultural contact—particularly within the homestay environment—prompted a re-evaluation of interactional norms. Rather than conforming to indirect responses typical in his home culture, Ken adapted to the more direct style of his host context, demonstrating a psychological and communicative adjustment consistent with

Berry’s (

1997) acculturation framework.

Ken’s TOEIC score increased to 570, a 195-point gain from Phase 1, placing him second among ten participants and above the national average (ETS, 2015a, cited in

Shimomura, 2016). His consistent study habits, workplace interactions, and sojourn experience contributed to this growth.

While detailed breakdowns within each ISS category are omitted due to word count constraints, total scores across the three data collection points offer a clear view of Ken’s developmental trajectory. In the initial round, Ken scored 80, placing him 3rd among 11 students, with the group average at 74.6 and a score range of 20. In the second round, his score increased to 81, maintaining his 3rd place rank, while the average rose slightly to 75.6 and the range narrowed to 18. By the final round, Ken achieved the highest score of 88, securing 1st place as the average dipped to 75.4 and the score range widened to 22. This progression highlights Ken’s growing distinction from his peers and suggests a significant development in his intercultural competence over time.

Overall, Ken’s trajectory exemplifies ideal ICC development. His proactive engagement, emotional resilience, and growing confidence—supported by structured learning, workplace dilemmas, and transformative experiences—demonstrate the interplay of formal and informal learning in shaping intercultural competence.

Ken’s third phase, collected after his study abroad experience, marks a significant progression in his intercultural competence. His Engagement and Confidence scores reach their highest levels, supported by proactive classroom choices, reflective journal entries, and transformative interactions abroad. While Enjoyment remains consistent, it is now accompanied by deeper emotional and linguistic integration. The contrast between Ken’s initial hesitation and his post-sojourn assertiveness illustrates a non-reversible shift in his communicative approach, aligning with

Mezirow’s (

1990) theory of transformational learning. Across all three phases, Ken’s trajectory—from tentative engagement to confident participation—demonstrates the cumulative impact of formal instruction, workplace dilemmas, and immersive intercultural experiences on ICC development.

This cumulative progression reflects and extends findings from previous studies on ICC development in ESL/EFL learners. Research by

Benson et al. (

2013) and

Fujio (

2018) highlights how immersive environments and informal interactions foster communicative competence beyond what is captured in standardised testing. Ken’s case supports this distinction, showing that ICC growth is shaped by sustained intercultural contact, reflective practice, and adaptive communication. His experience also reinforces

Deardorff’s (

2020) call for integrating formal and informal learning, and

Roever and Dai’s (

2021) emphasis on interactional competence as a key outcome of real-world language use. By documenting Ken’s development across structured instruction, workplace dilemmas, and study abroad, this study contributes to a growing body of evidence that ICC is best cultivated through socially embedded, experiential learning.

6. Discussion

The findings address the research questions concerning students’ intercultural knowledge, experience, and ICC development during university. Ken’s trajectory illustrates how ICC can evolve through a combination of formal instruction, real-world interaction, and immersive intercultural experiences. His pre-tertiary exposure to international peers laid the foundation for Engagement, which remained consistently high throughout the study. During his BA programme, Ken’s ISS scores reflected steady Enjoyment and a marked increase in Confidence, particularly following his study abroad experience.

In year one, Ken’s ICC development was initiated through classwork, journal reflections, and interactions in his international workplace. His efforts to navigate communication with diverse colleagues and his emotional responses to intercultural encounters demonstrated early signs of competence. By year two, Ken’s Confidence began to rise as he sought academic support for workplace communication and identified improvements in listening and pronunciation. His second-year data showed a shift from passive exposure to intentional participation, aligning with

Crane and Sosulski’s (

2020) concept of workplace dilemmas as catalysts for transformation.

Ken’s study abroad experience in Australia marked a turning point. His decision to take an optional cultural class and his reflections on direct communication illustrate a non-reversible shift in his communicative approach, consistent with

Mezirow’s (

1990) theory of transformational learning. Observing his host brother’s assuredness prompted Ken to reassess his own communicative style, leading to increased Confidence and a more assertive presence in intercultural interactions. His journal entries and interview excerpts reveal a growing comfort with ambiguity and a willingness to prioritise clarity over grammatical precision. This shift also reflects acculturative learning, as defined by

Berry (

1997), where sustained intercultural contact prompts psychological and communicative adaptation. Ken’s move toward directness in communication—departing from culturally normative indirectness—illustrates a deeper change in style shaped by immersion in the host environment. By framing this development through acculturation theory, the study highlights how study abroad fosters not only linguistic growth but also intercultural adjustment in communicative behaviour.

This transformation invites closer examination of Ken’s positioning and communicative choices within intercultural contexts. Throughout the study, he actively sought out opportunities for interaction—whether through workplace communication, study abroad, or interactions with host family members—demonstrating a proactive stance toward learning. His decision to take initiative in unfamiliar settings and to reflect critically on his communicative style suggests that he was not a passive recipient of intercultural exposure, but an agentive participant shaping his own learning trajectory. This agency is particularly evident in his shift from viewing himself as a language learner to a language user, and in his willingness to adopt communicative strategies that diverged from cultural norms. Recognising this agency is essential for understanding how learners negotiate identity and competence in intercultural spaces.

Interactional competence emerged as a key dimension of Ken’s development. It was assessed through a multimodal analysis of journal entries, interview data, and ISS scores, which together captured his evolving ability to manage real-time communication in intercultural contexts. This competence was not measured through isolated linguistic features, but through his adaptive use of language in socially and culturally situated interactions. Key indicators included journal reflections on workplace dilemmas and host family interactions, interview excerpts showing his awareness of pragmatic choices (e.g., prioritising clarity over grammatical accuracy), and rising ISS Confidence scores following study abroad. These data points align with

Mezirow’s (

1997) transformational learning theory, where disorienting experiences—such as struggling to be understood or observing unfamiliar communicative norms—prompt reflection and lead to lasting change. Ken’s transformation was evident in his repositioning from passive learner to autonomous communicator, and in his strategic use of interactional competence to assert agency in intercultural spaces.

Upon returning to Japan, Ken’s shift toward directness and communicative clarity stood in contrast to cultural norms that often favour indirectness and group harmony. His assertiveness and confidence suggest a repositioning—not as a passive learner conforming to traditional expectations, but as a communicator navigating intercultural spaces with greater autonomy. His consistent efforts to improve his English proficiency—through TOEIC preparation, workplace communication, and study abroad—demonstrate a form of self-advocacy. Seeking academic support and reflecting on his communicative style indicate a conscious commitment to shaping his own language journey, rather than relying solely on institutional structures.

This repositioning is meaningful not only for his personal development but also for what it reveals about the potential of immersive and informal learning environments to foster ICC. His trajectory illustrates how learners can move beyond test-oriented goals to develop adaptive, context-sensitive communication strategies—an outcome that holds implications for language education policy and practice in Japan. Ken’s consistent documentation of TOEIC study and his 195-point score increase reflect his dedication to formal learning. In contrast, his peers focused more on digital practices unrelated to structured language development. This contrast supports

Deardorff’s (

2020) argument for integrating formal and informal learning. Ken’s approach—combining TOEIC preparation with real-world intercultural communication—demonstrates how interactional competence, as described by

Roever and Dai (

2021), enhances communicative effectiveness.

While Ken’s development was supported by informal learning opportunities such as workplace communication and homestay interactions, these experiences were central to his ICC growth. Unlike formal instruction, these interactions were spontaneous, context-rich, and personally meaningful, allowing Ken to apply language in real-time and adapt his communicative style. His case illustrates how such experiences, though not formally assessed, play a central role in shaping communicative proficiency and cultural adaptability. Their impact highlights the need to recognise informal learning as a distinct and valuable component of ICC development, rather than viewing it as peripheral to academic achievement.

Despite Japan’s compulsory English education, the emphasis on grammar and reading often fails to develop spoken proficiency (

Igarashi, 2022;

Inuzuka, 2017). Limited opportunities for intercultural interaction (

Takeshita, 2016) further hinder ICC development. Ken’s initial lack of Confidence, despite early exposure, underscores this gap. However, his post-sojourn growth highlights the importance of immersive experiences and real-time communication in building ICC. His case supports findings that study abroad may not dramatically improve test scores but can significantly enhance ICC (

Fujio, 2018). His interactions with host nationals and proactive communication with his host brother contributed to his Confidence and Engagement.

Benson et al. (

2013) emphasise that language learning is inherently social and shaped by cultural context. Ken’s integration into Australian life and his daily use of English exemplify this principle.

Ken’s communicative approach extended beyond grammar and testing. His increased Confidence, reflected in ISS scores and interview data, was built through meaningful interactions in Tokyo and Australia. By the end of the project, Ken no longer expressed concern about his speaking ability. His focus shifted toward being understood, even if his language was imperfect—a key marker of interactional competence and ICC.

Ken’s developmental trajectory also resonates with broader research on learner motivation and intercultural learning.

Kikuchi (

2015) highlights how Japanese EFL learners’ engagement is shaped by both institutional structures and personal agency, a dynamic reflected in Ken’s shift from tentative participation to proactive classroom involvement. Similarly,

Wibowo et al. (

2024) emphasizes the role of critical reflection learning in fostering intercultural competence showing that meaningful learning occurs when learners actively process their experiences. This emphasis on reflection is mirrored in Ken’s journal entries, workplace dilemmas, and study abroad experiences, reinforcing the importance of socially embedded learning environments and supporting the argument that ICC development is best cultivated through the interplay of formal instruction and informal, real-world interaction.

This perspective also aligns with critiques of Japan’s English education system. The limitations of Japan’s English education system, particularly its lack of emphasis on ICC and learner agency (

Hanada, 2019), are evident in Ken’s early uncertainty. Study abroad provided a space for Ken to reposition himself—not just as a learner, but as an active user of English (

Deacon & Miles, 2023). His transformation was not solely linguistic but also behavioural, as he adopted more direct communication styles and advocated for himself in intercultural settings.

Ken’s development across the three phases—high Engagement, consistent Enjoyment, and increasing Confidence—demonstrates a clear trajectory of ICC growth. His final reflection, “…it would be better to be as direct as possible, without getting caught up in my lack of English” (Excerpt 12), encapsulates his shift toward communicative clarity and self-assurance. Ken’s ability to interact effectively in a second language, supported by his Engagement, Enjoyment, and Confidence, exemplifies ICC as defined in the literature. This progression also reflects his growing interactional competence, shaped by immersive experiences and critical reflection—key components of transformational learning.

These findings suggest that ICC development requires more than language instruction—it demands opportunities for real-time interaction, cultural immersion, and reflective practice. The ISS categories of Engagement, Enjoyment, and Confidence offer a valuable framework for assessing second language learners’ progress. Ken’s experience shows that when students consistently apply language skills in authentic intercultural contexts, they can achieve meaningful growth in both language proficiency and intercultural competence. In addition, his case highlights how interactional competence—developed through immersive and reflective experiences—can support this growth, reinforcing the value of experiential learning in ICC development.

7. Conclusions

This study explored the development of intercultural competence in one Japanese university student, Ken, through a longitudinal analysis of his formal and informal learning experiences, using journal entries and interviews collected over multiple phases. Drawing on

Mezirow’s (

1997) theory of transformational learning and

Crane and Sosulski’s (

2020) concept of workplace dilemmas, the findings illustrate how intercultural development can emerge through reflective practice, real-world interaction, and immersion in unfamiliar cultural contexts.

Berry’s (

1997) acculturation framework further supports this interpretation, highlighting how sustained intercultural contact—particularly during study abroad—can prompt psychological and communicative adaptation.

The study has addressed the research questions by offering a detailed account of one student’s intercultural competence development during undergraduate studies. In response to the first question, Ken entered university with a language repertoire shaped by prior English learning and informal intercultural experiences, including travel and social interactions, which provided a foundation for his participation in intercultural learning. Regarding the second question, the longitudinal data reveal that Ken’s ICC developed through a dynamic interplay of formal instruction, informal encounters, and reflective practice. His journal and interview responses show increasing awareness of cultural complexity, shifts in communicative strategies, and a growing capacity to navigate intercultural dilemmas. These findings underscore the value of multimodal data collection in capturing the layered and evolving nature of ICC development and suggest that both individual dispositions and contextual factors play a salient role in shaping learning trajectories.

Ken’s journey—from early exposure to international peers, through workplace communication challenges, to a transformative study abroad experience—demonstrates how learners can shift from initial uncertainty to a more assured and effective communicative approach. His reflections and interactions reveal a growing ability to navigate diverse cultural settings, express himself clearly, and respond effectively in real-time conversations. These changes reflect a broader evolution in communicative style, shaped by both structured learning and experiential immersion. This evolution aligns with acculturative learning, where Ken’s communicative adjustments—such as increased directness and assertiveness—reflect deeper cultural adaptation beyond linguistic proficiency.

While study abroad is often viewed as a key catalyst for intercultural growth, Ken’s experience shows that meaningful development can also occur through local interactions and sustained reflection. His case highlights the importance of integrating practical language use with intercultural exposure, whether in physical or virtual environments. Online platforms, collaborative projects, and culturally diverse workplaces offer alternative pathways for learners to engage with difference and develop communicative flexibility.

A central insight from this research is the interdependence of language acquisition and intercultural competence. Ken’s improvement in English proficiency was not solely the result of formal study, but of applying language in authentic intercultural contexts. His development underscores the limitations of test-oriented approaches and the need for pedagogies that prioritise interaction, reflection, and adaptability.

To support such development, Japanese universities should provide students with opportunities for direct dialogue, reflective exercises, and access to cultural resources both inside and outside the classroom. These elements foster practical language application and cultivate the skills necessary for intercultural understanding.

Although this study focused on a single learner, it points to broader implications for language education. Future research should expand to include diverse learners and contexts—both in-person and online—to better understand how intercultural competence and language proficiency co-evolve. By examining a wider range of interactions, educators can design programmes that more effectively support students’ communicative growth and global readiness.

Ken’s progression in intercultural competence appears to be critically shaped by two interrelated factors: his personal motivation and his pre-existing intercultural exposure. Throughout the data, Ken demonstrates a sustained interest in engaging with cultural difference, which may have amplified his responsiveness to reflective opportunities and supported his navigation of complex intercultural dilemmas. This motivation likely contributed to his willingness to interrogate assumptions and embrace alternative perspectives, aligning with

Mezirow’s (

1997) framework of transformative learning. Additionally, Ken’s prior experiences with cultural diversity—such as working with international colleagues and customers in a Tokyo café—may have provided him with familiar reference points and interpretive strategies that helped him make sense of new intercultural encounters. These experiences likely supported his ability to recognise communicative norms, anticipate misunderstandings, and adjust his responses accordingly. While these factors may have facilitated his ICC development, they also raise questions about the extent to which such predispositions shape learning trajectories, suggesting a need for further research into how individual histories and dispositions interact with structured intercultural learning environments.

While this study offers valuable insights into the development of intercultural competence, several limitations should be noted. First, the reliance on self-reported data—particularly journal entries and interviews—introduces the possibility of selective recall and subjective interpretation. Ken’s reflections may emphasize certain experiences while omitting others, potentially shaping the narrative of his development in ways that are not fully representative. Second, as a single case study, the findings are context-specific and not intended to be generalized across broader populations. Ken’s unique background, motivations, and learning environment may differ significantly from those of other students, limiting the transferability of the results. These limitations highlight the need for future research involving multiple participants and triangulated data sources to deepen understanding of ICC development in diverse educational contexts.