Pre-Service Teachers’ Beliefs About the Executive Functions of Gifted Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arffa, S. (2007). The relationship of intelligence to executive function and non-executive function measures in a sample of average, above average, and gifted youth. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology: The Official Journal of the National Academy of Neuropsychologists, 22(8), 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensio, D., Fernández-Mera, A., & Duñabeitia, J. A. (2023). The cognitive profile of intellectual giftedness. International Journal of Educational Psychology, 12(3), 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubry, A., Gonthier, C., & Bourdin, B. (2021). Explaining the high working memory capacity of gifted children: Contributions of processing skills and executive control. Acta Psychologica, 218, 103358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, A., Monge-López, C., & Gómez-Hernández, P. (2021). Percepciones docentes hacia las altas capacidades intelectuales: Relaciones con la formación y experiencia previa [Teachers perceptions towards high intelectual capacities: Relations with training and previous experience]. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 24(1), 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Algarín, E., Sarasola-Sánchez-Serrano, J. L., Fernández-Reyes, T., & García-González, A. (2021). Déficit en la formación sobre altas capacidades de egresados en magisterio y pedagogía: Un hándicap para la educación primaria en Andalucía [Deficit in training on high abilities of graduates in education and pedagogy: A handicap for primary education in Andalucia]. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 39(1), 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudson, T. G., & Preckel, F. (2013). Teachers’ implicit personality theories about the gifted: An experimental approach. School Psychology Quarterly, 28, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bracken, B. A., & Brown, E. F. (2006). Behavioral identification and assessment of gifted and talented students. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 24(2), 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracken, B. A., & Keith, L. K. (2004). CAB, clinical assessment of behavior: Professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Bucaille, A., Jarry, C., Allard, J., Brochard, S., Peudenier, S., & Roy, A. (2022). Neuropsychological profile of intellectually gifted children: A systematic review. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 28(4), 424–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucaille, A., Jarry, C., Allard, J., Brosseau-Beauvir, A., Ropars, J., Brochard, S., Peudenier, S., & Roy, A. (2023). Intelligence and executive functions: A comprehensive assessment of intellectually gifted children. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology: The Official Journal of the National Academy of Neuropsychologists, 38(7), 1035–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conesa, P. J., Onandía-Hinchado, I., & Duñabeitia, J. A. (2023). Validation and reliability of the Childhood Executive Function Inventory (CHEXI) in Spanish primary school students. Revista de Psicología Clínica con Niños y Adolescentes, 10(3), 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X., & Shi, J. (2014). Attentional switching in intellectually gifted and average children: Effects on performance and ERP. Psychological Reports, 114(2), 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrándiz, C., Ferrando-Prieto, M., Infantes-Paniagua, Á., Fernández Vidal, M. C., & Pons, R. M. (2025). Pre-service teachers’ perceptions of physical, socioemotional and cognitive traits in gifted students: Unveiling bias? Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 6, 1472880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- François-Sévigny, J., Pilon, M., & Gauthier, L. A. (2022). Differences in parents and teachers’ perceptions of behavior manifested by gifted children with ADHD compared to gifted children without ADHD and non-gifted children with ADHD using the conners 3 scale. Brain Sciences, 12(11), 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, F. (2018). Attitudes toward gifted education: Retrospective and prospective update. Psychological Test and Assessment Modeling, 60(4), 403. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore, C., & Cragg, L. (2014). Teachers’ understanding of the role of executive functions in mathematics learning. Mind, Brain, and Education, 8(3), 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez de la Peña, A., López-Zamora, M., Vila, O., Sánchez, A., & Thorell, L. B. (2022). Validation of the Spanish version of the Childhood Executive Functioning Inventory (CHEXI) in 4–5-year-old children. Anales de Psicología, 38(1), 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, G. A., Isquith, P. K., Guy, S. C., & Kenworthy, L. (2000). Behavior rating inventory of executive function: BRIEF. Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Golle, J., Schils, T., Borghans, L., & Rose, N. (2023). Who is considered gifted from a teacher’s perspective? A representative large-scale study. Gifted Child Quarterly, 67(1), 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Labrador, C. M. (2021). Actitudes y cambios en las actitudes de los docentes extremeños hacia las altas capacidades, a través de la formación en el tratamiento educativo de estos alumnos [Attitudes and changes in the attitudes of extremadura teachers towards high abilities, through training in the educational treatment of these students] [Doctoral thesis, Universidad de Extremadura]. [Google Scholar]

- Hattie, J. (2023). Visible learning: The sequel: A synthesis of over 2100 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawabreh, R., Danju, İ., & Salha, S. (2022). Exploring the characteristics of gifted pre-school children: Teachers’ perceptions. Sustainability, 14(5), 2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J., Howard, S. J., & Pascual-Leone, J. (2024). Two attentional processes subserving working memory differentiate gifted and mainstream students. Journal of Cognition, 7(1), 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karbach, J., & Unger, K. (2014). Executive control training from middle childhood to adolescence. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, A. V. (2010). Link between executive functioning and teacher referrals for gifted testing [Doctoral dissertation, Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine]. PCOM Psychology Dissertations. Paper 69. Available online: https://digitalcommons.pcom.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1068&context=psychology_dissertations (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Kornmann, J., Zettler, I., Kammerer, Y., Gerjets, P., & Trautwein, U. (2015). What characterizes children nominated as gifted by teachers? A closer consideration of working memory and intelligence. High Ability Studies, 26(1), 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leikin, M., Paz-Baruch, N., & Leikin, R. (2013). Memory abilities in generally gifted and excelling-in-mathematics adolescents. Intelligence, 41(5), 566–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Rivas, L., & Calero-García, M. D. (2018). Sobredotación, talento e inteligencia normal: Diferencias en funciones ejecutivas, potencial de aprendizaje, estilo cognitivo y habilidades interpersonales [Giftedness, talent and normal intelligence: Differences in executive functions, learning potential, cognitive style and interpersonal skills]. Revista de Educación Inclusiva, 11(1), 91–111. [Google Scholar]

- Matheis, S., Keller, L. K., Kronborg, L., Schmitt, M., & Preckel, F. (2020). Do stereotypes strike twice? Giftedness and gender stereotypes in pre-service teachers’ beliefs about student characteristics in Australia. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 48(2), 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, A., Emerson, M. J., & Friedman, N. P. (2000). Assessment of executive functions in clinical settings: Problems and recommendations. Seminars in Speech and Language, 21(2), 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyake, A., & Friedman, N. P. (2012). The nature and organization of individual differences in executive functions: Four general conclusions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(1), 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Arenas, D. A., Aguirre-Acevedo, D. C., Díaz Soto, C. M., & Pineda Salazar, D. A. (2018). Executive functions and high intellectual capacity in school-age: Completely overlap? International Journal of Psychological Research, 11(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Arenas, D. A., Trujillo-Orrego, N., & Pineda-Salazar, D. (2010). Capacidad intelectual y función ejecutiva en niños intelectualmente talentosos y en niños con inteligencia promedio [Intellectual capacity and executive function in intellectually gifted children and in children with average intelligence]. Universitas Psychologica, 9(3), 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Zevada, M. E. (2018). Análisis conductual y electrofisiológico de funciones ejecutivas en adolescentes con capacidad intelectual alta y capacidad intelectual media [Behavioral and electrophysiological analysis of executive functions in adolescents with high intellectual capacity and average intellectual capacity] [Doctoral dissertation, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos]. Available online: http://riaa.uaem.mx/handle/20.500.12055/1407 (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Owens, A. (2021). Teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about executive functions utilized in reading instruction (Publication number 28542717) [Dissertation thesis, McKendree University]. ProOuest Dissertations and Theses Global. [Google Scholar]

- Palomino, C. I., & Brudvig, A. (2022). Examining the role of demographic characteristics, attachment, and language in preschool children’s executive function skills. Early Child Development and Care, 192(12), 1967–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasarín-Lavín, T., García, T., Abín, A., & Rodríguez, C. (2024). Neurodivergent students. A continuum of skills with an emphasis on creativity and executive functions. Applied Neuropsychology: Child, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasarín-Lavín, T., Rodríguez, C., & García, T. (2021). Conocimientos, percepciones y actitudes de los docentes hacia las altas capacidades. Revista de Psicología y Educación, 16(2), 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preckel, F., Baudson, T. G., Krolak-Schwerdt, S., & Glock, S. (2015). Gifted and maladjusted? Implicit attitudes and automatic associations related to gifted children. American Educational Research Journal, 52(6), 1160–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, S., Rubinsten, O., & Katzir, T. (2016). Teachers’ beliefs and practices regarding the role of executive functions in reading and arithmetic. Frontiers of Psychology, 7, 1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A., Almeida, L., & Perales, R. G. (2020). Comparison of gifted and non–gifted students’ executive functions and high capabilities. Journal for the Education of Gifted Young Scientists, 8(4), 1397–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Naveiras, E., Verche, E., Hernández-Lastiri, P., Montero, R., & Borges, Á. (2019). Differences in working memory between gifted or talented students and community samples: A meta-analysis. Psicothema, 31(3), 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, C., Brigaud, E., Moliner, P., & Blanc, N. (2022). The social representations of gifted children in childhood professionals and the general adult population in France. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 45(2), 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J., Tao, T., Chen, W., Cheng, L., Wang, L., & Zhang, X. (2013). Sustained attention in intellectually gifted children assessed using a continuous performance test. PLoS ONE, 8(2), e57417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofologi, M., Papantoniou, G., Avgita, T., Lyraki, A., Thomaidou, C., Zaragas, H., Ntritsos, G., Varsamis, P., Staikopoulos, K., Kougioumtzis, G., Papantoniou, A., & Moraitou, D. (2022). The gifted rating scales-preschool/kindergarten form (GRS-P): A Preliminary examination of their psychometric properties in two Greek Samples. Diagnostics, 12(11), 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosic-Vasic, Z., Keis, O., Lau, M., Spitzer, M., & Streb, J. (2015). The impact of motivation and teachers’ autonomy support on children’s executive functions. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(6), 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spataro, P., Morelli, M., Pirchio, S., Costa, S., & Longobardi, E. (2023). Exploring the relations of executive functions with emotional, linguistic, and cognitive skills in preschool children: Parents vs. teachers reports. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 39, 1045–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, H., Taki, Y., Hashizume, H., Sassa, Y., Nagase, T., Nouchi, R., & Kawashima, R. (2011). Failing to deactivate: The association between brain activity during a working memory task and creativity. NeuroImage, 55(2), 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanabe, M. K., Whitaker, A. M., O’Callaghan, E. T., Murray, J., & Houskamp, B. M. (2014). Intellectual ability as a predictor of performance on the Wisconsin card-sorting test. Applied Neuropsychology: Child, 3(4), 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorell, L. B., & Nyberg, L. (2008). The Childhood Executive Functioning Inventory (CHEXI): A new rating instrument for parents and teachers. Developmental Neuropsychology, 33(4), 536–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toplak, M. E., West, R. F., & Stanovich, K. E. (2013). Practitioner review: Do performance-based measures and ratings of executive function assess the same construct? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 54(2), 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana-Sáenz, L., Sastre-Riba, S., & Urraca-Martínez, M. L. (2021). Executive function and metacognition: Relations and measure on high intellectual ability in typical schoolchildren. Sustainability, 13, 13083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana-Sáenz, L., Sastre-Riba, S., Urraca-Martínez, M. L., & Botella, J. (2020). Measurement of executive functioning and high intellectual ability in childhood: A comparative meta-analysis. Sustainability, 12(11), 4796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyns, T., Preckel, F., & Verschueren, K. (2021). Teachers-in-training perceptions of gifted children’s characteristics and teacher-child interactions: An experimental study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 97, 103215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierenga, L. M., Bos, M. G. N., van Rossenberg, F., & Crone, E. A. (2019). Sex effects on development of brain structure and executive functions: Greater variance than mean effects. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 31(5), 730–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, N., & Imai-Matsumura, K. (2019). Gender differences in executive function and behavioural self-regulation in 5 years old kindergarteners from East Japan. Early Child Development and Care, 189(1), 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelazo, P. D., Blair, C. B., & Willoughby, M. T. (2016). Executive function: Implications for education. NCER 2017–2000. National Center for Education Research. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED570880 (accessed on 25 July 2025).

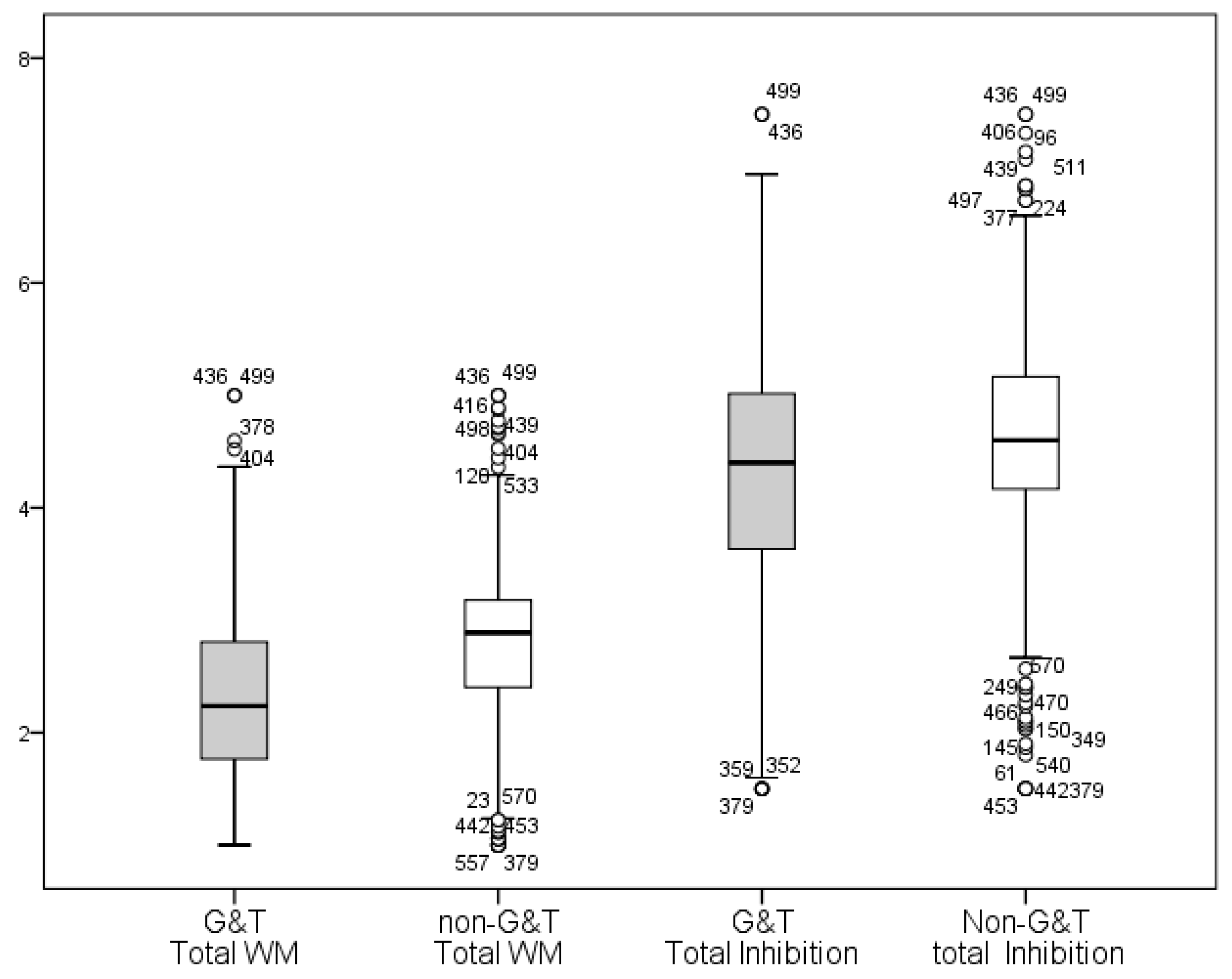

| Executive Functions | M (SD) | Skewness | Kurtosis | Kolmogorov–Smirnov | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G&T | Working memory | 2.21 (0.71) | 0.492 | 0.386 | ks = 0.052 *** |

| Planning | 2.31 (0.78) | 0.205 | −0.108 | ks = 0.085 *** | |

| Total WM | 2.26 (0.73) | 0.339 | 0.168 | ks = 0.042 ** | |

| Regulation | 3.12 (0.87) | 0.071 | −0.42 | ks = 0.089 *** | |

| Inhibition | 2.74 (0.74) | −0.064 | 0.154 | ks = 0.086 *** | |

| Total Inhibition | 4.31 (1.08) | −0.091 | 0.10 | ks = 0.05 ** | |

| Non-G&T | Working memory | 2.86 (0.74) | −0.2 | 0.697 | ks = 0.118 *** |

| Planning | 2.75 (0.78) | −0.027 | 0.552 | ks = 0.121 *** | |

| Total WM | 2.81 (0.73) | −0.11 | 0.10 | ks = 0.092 *** | |

| Regulation | 3.22 (0.71) | −0.256 | 0.654 | ks = 0.112 *** | |

| Inhibition | 2.99 (0.70) | −0.375 | 0.806 | ks = 0.114 *** | |

| Total Inhibition | 4.60 (0.98) | −0.39 | 1.136 | ks = 0.081 *** |

| EFs | Mean Rank Positive (Favor G&T) | Mean Rank Negative (Favor Non-G&T) | Related Samples Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test Summary | Effect Size (r) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Working memory | 307.74 (442) | 119.8 (102) | Z = −16.87 ** | −0.700 |

| Planning | 200.58 (294) | 123.92 (75) | Z = −12.16 ** | −0.505 |

| Total WM | 302.22 (438) | 149.71 (106) | Z = −15.89 *** | −0.724 |

| Regulation | 195.32 (244) | 209.82 (157) | Z = −3.17 ** | −0.132 |

| Inhibition | 152.69 (144) | 203.42 (261) | Z = −8.52 ** | −0.354 |

| Total Inhibition | 234.31 (295) | 202.39 (151) | Z = −7.08 *** | −0.681 |

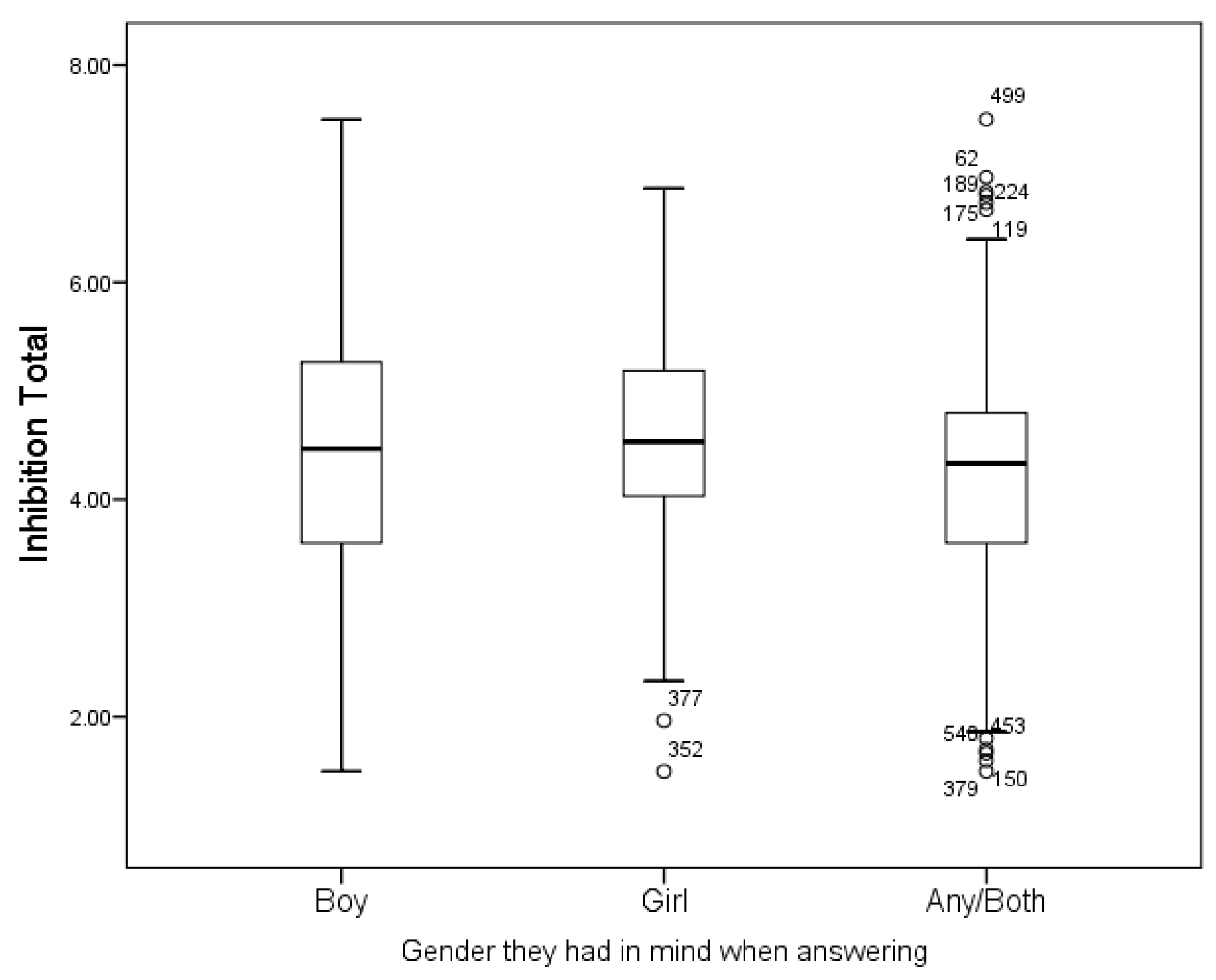

| Independent Samples Kruskal–Wallis Test | Adjusted Significance Values of Pairwise Comparisons | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boy/Girl | Boy/Any | Girl/Any | ||

| Working memory | ks(2) = 7.158, p = 0.028 | 0.534 | 0.046 | 1.000 |

| Planning | ks(2) = 9.588, p = 0.008 | 0.150 | 0.014 | 1.000 |

| WM Total | ks(2) = 8.67, p = 0.013 | 0.288 | 0.021 | 1 |

| Regulation | ks(2) = 8.266, p = 0.016 | 0.4683 | 1.000 | 0.024 |

| Inhibition | ks(2) = 4.687, p = 0.09 | 1.000 | 0.501 | 0.63 |

| Inhibition Total | ks = 7.184, p = 0.028 | 1.00 | 0.755 | 0.078 |

| Differences Depending on Previous Training in G&T | Differences Depending on Whether They Know Someone with G&T | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training in G&T (n = 63) | No Training in G&T (n = 63) | Know G&T (n = 324) | Not Know G&T (n = 255) | |||||

| EFs | Mean Rank | Mean Rank | Z | Effect Size (r) | Mean Rank | Mean Rank | Z | Effect Size (r) |

| WM | 60.18 | 68.68 | −1.29 | 0.11 | 279.18 | 303.75 | −1.75 | 0.07 |

| Planning | 61.10 | 67.79 | −1.02 | −0.09 | 277.50 | 305.89 | −2.04 * | −0.08 |

| Total WM | 60.40 | 68.47 | −1.23 | −0.11 | 278.13 | 306.15 | −2.00 * | −0.08 |

| Regulation | 69.95 | 59.22 | −1.64 | −0.14 | 287.93 | 292.63 | −0.33 | −0.01 |

| Inhibition | 66.72 | 62.35 | −0.66 | 0.05 | 278.68 | 304.38 | −1.84 | 0.07 |

| Total Inhibition | 68.72 | 60.41 | −1.27 | −0.11 | 280.58 | 303.05 | −1.60 | −0.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Checa Fernández, P.; Ferrándiz, C.; Ferrando-Prieto, M.; Pons Parra, R. Pre-Service Teachers’ Beliefs About the Executive Functions of Gifted Students. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091206

Checa Fernández P, Ferrándiz C, Ferrando-Prieto M, Pons Parra R. Pre-Service Teachers’ Beliefs About the Executive Functions of Gifted Students. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091206

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheca Fernández, Purificacion, Carmen Ferrándiz, Mercedes Ferrando-Prieto, and Rosa Pons Parra. 2025. "Pre-Service Teachers’ Beliefs About the Executive Functions of Gifted Students" Education Sciences 15, no. 9: 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091206

APA StyleCheca Fernández, P., Ferrándiz, C., Ferrando-Prieto, M., & Pons Parra, R. (2025). Pre-Service Teachers’ Beliefs About the Executive Functions of Gifted Students. Education Sciences, 15(9), 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091206