1. Introduction

For centuries, debate has been viewed as a link between verbal discussion and intellectual argumentation. Ancient Greece was the first civilization in which citizens employed debate in their instruction and daily lives as philosophers and intellectuals. Debate is still employed as a strategy in the teaching and political spheres. The ability to engage in crucial discussions, express points of view, and refute others’ arguments is considerably valuable and must be developed and stressed in education.

Debate is an instructional strategy that fosters high-order thinking skills. It enables students to generate and organize arguments, apply them in various contexts, analyze them carefully, include explanations and examples to convince their opponents, evaluate the presented arguments, and make decisions. It creates a meaningful learning environment that allows learners to use the language purposefully while mastering communication skills. When conducted via platforms such as Zoom, debate also becomes an innovative method for teaching English, as it provides students with authentic opportunities to practice the target language in real-time discussions, strengthen their academic writing, and enhance both oral and written argumentation skills in a virtual setting.

Moreover, debate facilitates teaching as a method that is aimed at developing and enhancing different aspects of the learner’s personality and performance, such as communicative and problem-solving skills, active listening, critical thinking, creativity, motivation, and adaptability, and it also allows the learner to gain knowledge and overcome stereotypes (

Kudinova & Arzhadeeva, 2020).

Debate serves as both a performance and a channel for sharing ideas and opinions. On this basis, educators and education policymakers prioritize improving pupils’ speaking skills by implementing this strategy (

Snider & Schnurer, 2006).

Debate serves as a performance of ideas and arguments as well as a method of transmission where communication occurs between two individuals, namely, the sender and the receiver. When an individual gives a speech, the first step of the process is encoding. The sender’s intention to transmit in code depends on the knowledge and point of view of the receiver (

Mathews, 1983). The written mode in debates is a way of mastering grammatical linguistics to form well-written texts. It emphasizes grammatical accuracy and linguistic structure coherence. In both written and oral modes, a message should be conveyed in context to constitute a meaning.

Furthermore, the context of debate is comprehensive: it can be political, cultural, social, or historical. The language used in different modes is used to express different perspectives, attitudes, and experiences (

Snider & Schnurer, 2002). It is a form of communication that is a mode of interaction with oneself, with others, and with internal and external environments (

Narula, 2006). Communication is not just the existence of the sender and the receiver but also a connection of inner thoughts that arise through the interaction with ourselves and others under certain conditions and with the influence of culture, attitude, thoughts, and ideology.

Many studies have focused on debate’s impact at a university level (

Al-Mahrooqi & Tabakow, 2015;

Nimasari et al., 2016;

Sabbah, 2015;

Terenzini et al., 1995). Most academics believe classroom discussion is a great way to teach speaking, critical thinking, and argumentation writing. Little if any research has examined how debates over Zoom affect high school students’ argumentation writing skills. This study examined secondary school debates and will discuss Zoom debates and how they benefit both teachers and students. In emergencies like pandemics, wars, political issues, and checkpoints, they identified a technique for cooperative learning that promotes socialization.

This study presents a unique investigation into using Zoom for debate instruction, a topic of particular interest to English teachers. It also aims to persuade teachers to use Zoom for debates and to modify their perspectives on applying technology in virtual classes. It focuses on high school students, specifically tenth and eleventh graders in a Palestinian high school, adding a distinct perspective to the existing literature.

1.1. Research Questions

RQ1: To what extent does Zoom debating enhance the critical thinking and argumentation writing of secondary students?

RQ2: Does Zoom debating influence students’ critical thinking and argumentation?

RQ3: Do students’ perspectives on social skills differ statistically significantly (α ≤ 0.05) as a result of the teaching method employed (debating via Zoom/traditional)?

RQ4. What is the impact of debating via the Zoom platform on students’ nonverbal communication?

1.2. Hypothesis

Questions included the following:

- 1.

Are there any statistically significant differences at (α ≤ 0.05) in the means of pre-test and post-test of writing skills and total scores due to the teaching method (traditional vs. debating via Zoom platform)?

- 2.

Are there any statistically significant differences at (α ≤ 0.05) in the means of pre-test and post-test of critical thinking skills and total score due to the teaching method (traditional vs. debating via Zoom).

- 3.

Are there any statistically significant differences at (α ≤ 0.05) between critical thinking skills and argumentation writing due to using the Zoom platform?

Questions for the second hypothesis

- 1.

Are there any statistically significant differences at (α ≤ 0.05) in the students’ perspectives toward the impact of debating via Zoom in enhancing students’ critical thinking and argumentation writing due to gender?

- 2.

Are there any statistically significant differences at (α ≤ 0.05) in the students’ perspectives toward the impact of debating via Zoom in enhancing students’ critical thinking and argumentation writing due to specialization?

- 3.

Are there any statistically significant differences at (α ≤ 0.05) in the students’ perspectives toward the impact of debating via Zoom in enhancing students’ critical thinking and argumentation writing due to grade?

- 4.

Are there any statistically significant differences at (α ≤ 0.05) in the students’ perspectives toward the impact of debating via Zoom platform in enhancing students’ critical thinking and argumentation writing due to teaching method (debating via Zoom/traditional)?

Questions for the third hypothesis

- 1.

Are there any statistically significant differences at (α ≤ 0.05) in the students’ perspectives toward social skills due to teaching method (Debating via Zoom/Traditional)

Questions for the fourth hypothesis

- 2.

Are there any statistically significant differences at (α ≤ 0.05) in the students’ perspectives toward nonverbal communication skills due to teaching method (debating via Zoom/traditional)

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

Vygotsky, the father of social constructivism theories, claimed in the 1920s and 1930s that social interaction is essential to an individual’s critical thinking process (

Kalina & Powell, 2009). Additionally, the literature maintained that “sociocultural theory focuses on the causal relationship between individual cognitive development and social interaction” (

Lourenço, 2012). Every function in a child’s cultural development, according to Vygotsky, manifests twice—internally (intra-psychological) and externally (inter-psychological), first on the social level and then on the individual level.

Vygotsky (

1978, p. 57) argues that language is a tool for fostering perception through culture and society (

Collins, 2000).

Regarding child development, Vygotsky extended the relationship between language, culture, and cognitive functions. The first occurs when the child works socially with adults, which he defined as inter-mental interaction among minds in sociocultural interaction situations. Adults help children develop their brains and linguistic skills, which leads to more sophisticated cognitive processes. Second, youngsters internalize language at the intra-mental level, making it seem as though they were born with it (

Miller, 2016).

Bates (

2019) added that “knowledge and interaction are constructed through social interactions with family, friends, teachers, and peers”.

The history of debate in the Arab world was utilized after the spread of Islam in different geographical areas; the Arabic language was exposed to and affected by many languages and dialects. As a result, a linguistic phenomenon called diglossia appeared. This occurs when two distinct codes with different functions appear due to a reason or a situation (

Wardhaugh & Fuller, 2021). Also, other changes in linguistic features appeared as a result of the dialectical pronunciation of specific articles (

Al Suwaiyan, 2018). Both affected the language learning ability of children (

Rass, 2015).

Moreover, Arabic and Hebrew are the official languages of the state. English was given the status of a foreign language, and the connection between Arabic dialects, English, and Hebrew has created a new linguistic reality. As a result of the language diversity in the Arab community, Hebrew became the integrative and dominant language (

Amara & Mar’i, 2002).

Children primarily acquire the Arabic language, as it is their mother tongue; they practice colloquial Arabic throughout early childhood in daily life. It is important to mention that the grammatical system of modern standard Arabic differs entirely from everyday Arabic; it is more sophisticated and involves rich and varied vocabulary expressions.

The Arab community is a collectivist, traditional, male-dominated, and less egalitarian culture (

Aarar, 2022). Arab communities are heterogeneous, consisting of Muslims, Christians, Jews, and others in the northern and central parts of the country, while it is a homogenous society in the south and triangle area (

Yehya, 2021).

In the Arab sector, English is considered a foreign language, and students are exposed to native speakers of the English language only occasionally and rarely in their community. According to high school teachers, teaching controversial issues increases the value of discussing evidence-based issues. Still, the practice of discussion in high schools is detrimental to a teacher and their career because of conflict and disputes that may occur in the classroom among students (

Byford et al., 2009). The literature shows that a lack of readiness and language preparation leads to weaknesses in language acquisition skills among Palestinian students in Israel at the age of six (

Rass, 2015).

It is also known that conducting online debates in high school is a sophisticated process for teachers. It requires pre-debate planning, such as students’ and teachers’ digital awareness, parents’ approval for their child’s participation, and online sources that encourage social interaction that fosters speaking and writing skills and encourages active listening. Therefore, for any online debate, not just debates via Zoom (DVZ), different factors need to be included for them to be successful, such as the students’ clear appearance on the screen, where their presence, facial expressions, bodily movement, paralinguistics, gestures, and eye contact are considered.

Debaters use all these traits to communicate their arguments in a way that draws in the opposing side, the judges, the audience, and peers, and this helps with progressing the discussion. The second is cognitive presence, which is awareness. Skilled debaters must employ several mental processes to persuade opponents in competitions by focusing on all the facts and understanding the context. Many academics associate Bloom’s taxonomy

1 with critical thinking and discussion. Thirdly, there is cultural awareness, where the debater’s religion, norms, standards, customs, traditions, and culture are crucial. Finally, the fourth factor is technological acceptance, which measures the students’ digital awareness and trust in virtual learning. The students’ engagement with Zoom, Google Meet, and other interactive video conferencing services enables them to be confident in their digital use, and they can openly share information and challenges in debate in breakout rooms and work together as well as individually.

This study entails utilizing a digital platform, Zoom, to instruct tenth- and eleventh-grade students in a Palestinian Arab high school on how to navigate contentious subjects through the facilitation of debates. The purpose of this study is to provide valuable insights for English teachers and experts in the domain of educational policy.

3. Methodology

This experimental study followed the quantitative methods of research. The collected data in the quantitative research method creates new knowledge (

Osborne, 2008), which examines the relationship between variables to test the theories. The variables are measurable, and the hypothesis can be tested based on instruments. The quasi-experiment is observational and resembles a true experiment, except for the use of a randomized sample (

Maciejewski, 2020). Pre- and post-tests were conducted, and the initial responses were compared with the final responses to obtain the final results.

According to reliability and validity, reliability represents the instrument’s ability to describe the attributes of the variables and to form consistency. Validity is examined if the research instrument measures the concept accurately (

LoBiondo-Wood & Haber, 2002). Internal reliability tests determine to what extent the experiment was designed, conducted, and analyzed, which permits reliable responses to the research questions (

Andrade, 2018). External consistency describes to what extent the researcher can generalize the results of the study to other contexts (

Egger et al., 2008) via Zoom through classroom observations before, during, and after the debate.

3.1. Research Population

This research involved 330 students. Arab high schools comprised 35% tenth graders and 65% eleventh graders. Tenth graders could pick two scientific or arts subjects.

3.2. Research Sample

The researcher selected 60 male and female students. The control group was from the other two classes, while the experimental group was from the tenth and eleventh grades of both schools (n = 30). Seven men and twenty-three women took ten 90 min tests. Traditional methods included teaching the four language skills, discussing questions, and taking textbook-based English matriculation tests.

Examined deliberation: Students studied English grammar, writing, speaking, and reading. Pre- and post-tests tested writing and critical thinking.

3.3. Research Instrument

In this study, various instruments were adopted; the first one is Watson and Glaser’s critical thinking appraisal exercise. Students responded to the tests before and after the study. The researcher also served as a teacher; she translated the test and simplified it before distributing it to answer the questions before and after the study. The second instrument was argumentation essay writing pre- and post-tests. The argumentation composition focused mainly on writing the introduction, expressing an opinion, mentioning the reasons to support the opinion, providing examples, writing counterarguments, and drawing a conclusion. The third instrument was a questionnaire, which was designed to respond to five domains, namely critical thinking, argumentation, social interaction, speaking skills, and non-verbal communication skills.

3.4. Research Variables

Study variables included men and women from classes ten and eleven. The subject categories were biology, chemistry, computing, sociology, ecology, and physics. Students used laptops, iPads, and phones. To involve school management, the quasi-experimental trial design required the principal’s permission to teach pupils debate skills via Zoom throughout the day. Mondays and Wednesdays were year-end classes. To improve instruction, researchers used Zoom, and data was collected 8 times. Each session comprised two 45 min lessons.

4. Results

Results of the collected data: To examine students’ views on Zoom debates and their effects on critical thinking and argumentation, the researcher assessed if pre- and post-test critical thinking skills changed significantly between groups.

Table 1 shows a 4.61 test statistic and a

p-value < 0.05.

Table 2 shows pre- and post-test Mann–Whitney tests of critical thinking skills in experimental and control groups. The pre-test scores for all critical thinking skills did not differ statistically between groups.

The experimental group outperformed the control group in all tested dimensions and scores. Inference, assumption recognition, deduction, interpretation, and argument evaluation were far higher in the experimental group than in the control group. The experimental group’s intervention improved critical thinking more than the control group.

The study demonstrated significant differences in argumentation writing skill scores between pre- and post-tests (α ≤ 0.05, test statistic 6.65,

p-value < 0.05), rejecting the null hypothesis.

Table 3 shows Wilcoxon test pre- and post-test scores for argumentation writing.

An α of 0.05, a test statistic of 6.65, and a Sig of 0.000 disproved the null hypothesis of no significant changes. Pre- and post-test results differ significantly, rejecting the null hypothesis. Instruction improved persuasion.

Table 4 contrasts control and experimental pre- and post-test Mann–Whitney tests.

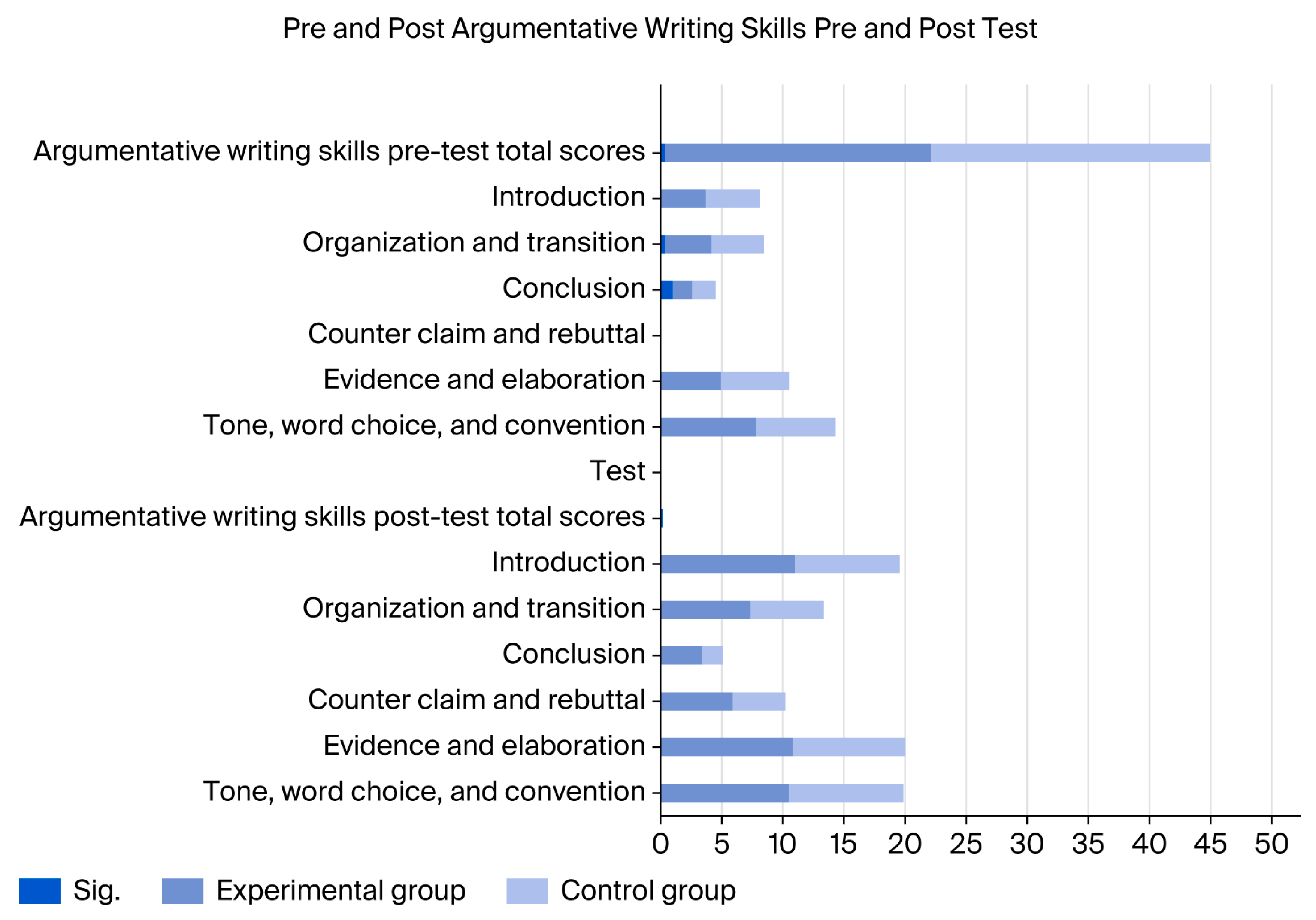

The argumentation test has the following eight sections: introduction, organization and transition, conclusion, counterclaim and rebuttal, evidence and elaboration, tone, word choice, and convention.

Results reveal that for the control group, the highest mean score results are for tone and word choice and convention for the experimental group, as shown in

Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows that the experimental group’s introduction post-test mean was M = 10.95, up from 3.63 in the pre-test, while the control group’s mean was M = 8.57. The control group’s evidence and elaboration mean scores were 10.80 and 9.25, significant at 0.004. Tone, term, and convention had an M of 10.55 in the control group and 9.35 in the experimental group. The test group had the lowest mean conclusion score, at 3.28, whereas the control group had 1.82. Zoom-taught debaters improved their rebuttal skills more in both groups, with M = 5.85 for experimental and 4.35 for control, sig 0.420.

4.1. The Impact of Debating via Zoom on Critical Thinking Skills

The Wilcoxon test and Zoom debates improve student critical thinking; see

Table 5.

The table provides the mean scores, weighted means, T-values, and p-values of seven critical thinking items. Zoom discussions improved critical thinking, specifically judging and summarizing disputed materials (p-values 0.022 and 0.040). Evidence-based text analysis was unaffected by lesson emphasis, inference, removal, concept integration, or rubrics. Zoom debates may increase students’ critical thinking and teaching.

4.2. The Impact of Debating via Zoom on Evidence-Based Writing Skills

On the other hand, Zoom assists in connecting the ideas of the written evidence-based text. Wilcoxon test results on the effects of Zoom debates on students’ evidence-based writing are shown in

Table 6.

The table presents seven evidence-based writing aspects, namely mean scores, weighted means, T-values, and p-values. Zoom debates enhance grammar and claims (0.043, 0.220). Statistics showed no improvement in introductions, conclusions, counterarguments, or claims. Zoom debates help evidence-based writing, but students need experience.

4.3. The Impact of Debating via Zoom on Social Skills

Zoom helps students express themselves freely and enhance their boldness. The Wilcoxon test results for the effects of Zoom discussions on students’ social skills are shown in

Table 7.

The table shows mean scores, weighted averages, T-values, and p-values for seven social skills development components. Research says Zoom debates increase student social skills. Students’ question-answering confidence rose (0.000). Student teamwork and communication improved substantially (0.013 and 0.201). Zoom debates helped kids socialize without prior respect or friendship.

4.4. The Impact of Debating via Zoom on Speaking Skills

Students claimed Zoom helps them talk before arguing. A statistical mean of 3.26, a weighted mean of 65.2%, and a *Sig (

p-value) of less than 0.05 showed that 65.2% of students thought Zoom improved speaking; see

Table 8.

The Wilcoxon test assesses Zoom debates’ impact on students’ speaking skills. Fluency, pronunciation, and language practice improved significantly. Overall, students’ speaking proficiency was positively affected by Zoom-based debates, while there were no significant changes in areas like topic definition and vocabulary usage.

4.5. The Impact of Debating via Zoom on Nonverbal Communication Skills

Research indicates that Zoom debates improve nonverbal communication skills for 57.4% of students, with a mean of 2.87, a weighted mean of 57.4%, and *Sig (

p-value) > α = 0.05.

Table 9 indicate pre-debate reactions to the influence of Zoom debates on nonverbal communication.

The Wilcox test examines students’ nonverbal communication during Zoom conversations. Students found they understood tone, nonverbal communication, and expressions better. The body gestures of other students and eye contact were significantly improved in Zoom debates.

Two groups’ questionnaire responses were compared before and after the Zoom debate using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Table 10 shows that the value of the test statistic is 4.07 and the

p-value is <0.05, which means that there is a significant difference between students’ opinions regarding the effect of debating via Zoom on critical thinking and evidence-based writing skills before and after using the technique.

Table 11 shows that students’ opinions on the impact of Zoom debates on critical thinking and evidence-based writing differ considerably before and after arguing (test statistic = 3.65,

p-value < 0.05). Control group students’ perspectives on the impact of Zoom debates on critical thinking and evidence-based writing before and after use are similar. The control group test value is 1.90 at

p > 0.05.

Table 12 compares experimental and control group students’ views on the impact of Zoom debates on their skills before and after arguing.

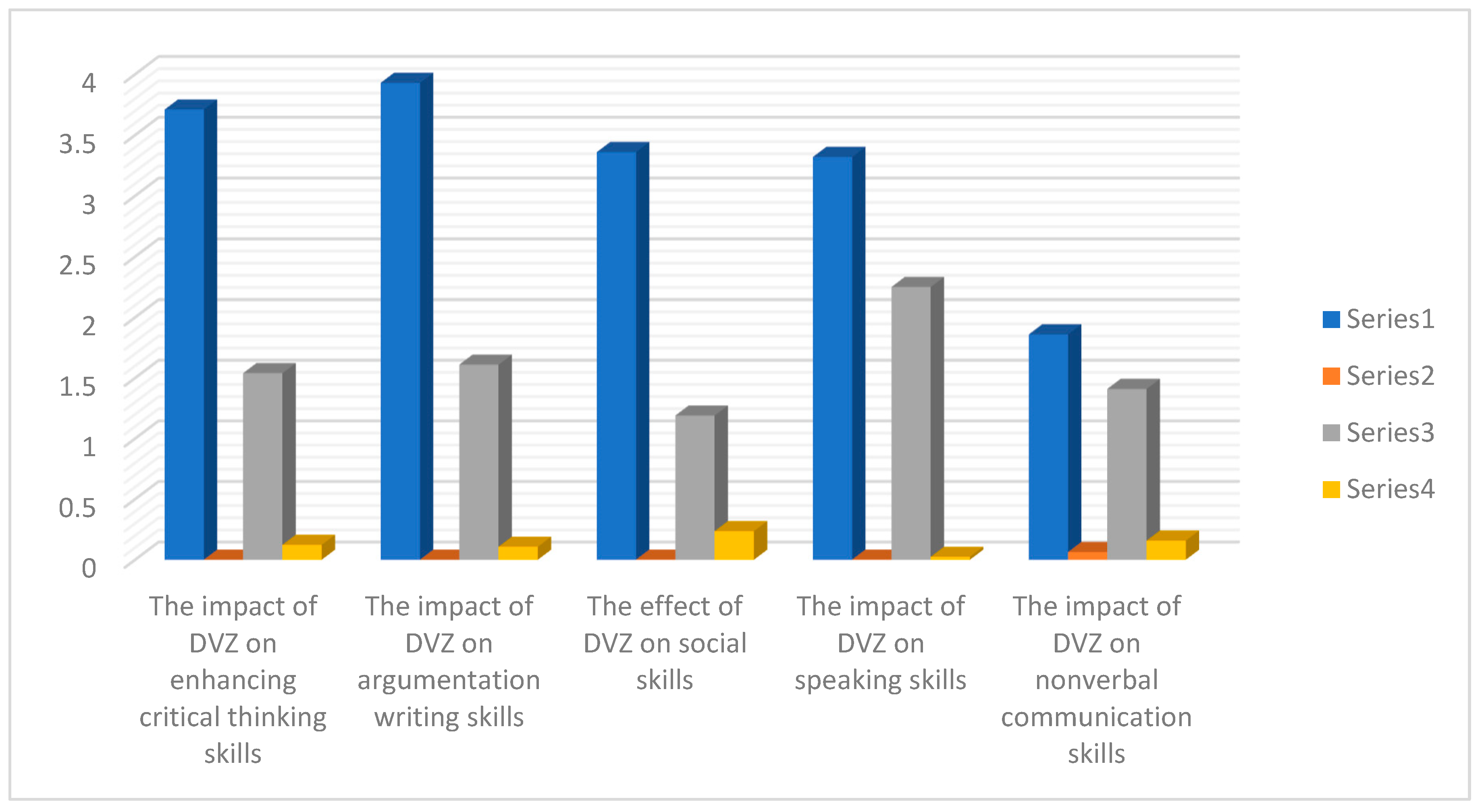

Figure 2 examines the average and standard deviation of survey responses collected before and after Zoom debates in different fields.

4.6. Students’ Perspectives Debating via Zoom as a Teaching Method

Table 13 shows the means and SDs for critical thinking, persuasive writing, social skills, speaking, and nonverbal communication. Zoom discussions improved student mean scores in many categories. Critical thinking, evidence-based writing, social skills, speaking, and nonverbal communication improved; mean scores were 2.87–3.65, 2.98–3.71, 3.28–3.83, 3.26–3.89, and 2.87–3.20. Each domain had consistent response variability and standard deviations before and after talks. Student skills developed with Zoom debates.

Student opinions on the impact of Zoom debate discussions on critical thinking and evidence-based writing changed before and after the trial.

Figure 2 compares pre- and post-experiment means for both groups.

The Mann–Whitney U test contrasts experimental and control students’ perspectives on the effects of Zoom debates on critical thinking and evidence-based writing skills due to the teaching method (traditional vs. Zoom). The researcher used the Mann–Whitney U test, as shown in

Table 14, to perform this comparison.

Zoom discussions do not affect students’ critical thinking and persuasive writing by specialization (see

Table 15;

p-values (*Sig) > 0.05). Therefore, specialization did not affect students’ perceptions of the impact of Zoom debate discussions on critical thinking and argumentation.

4.7. Debating via Zoom Regarding Specialization

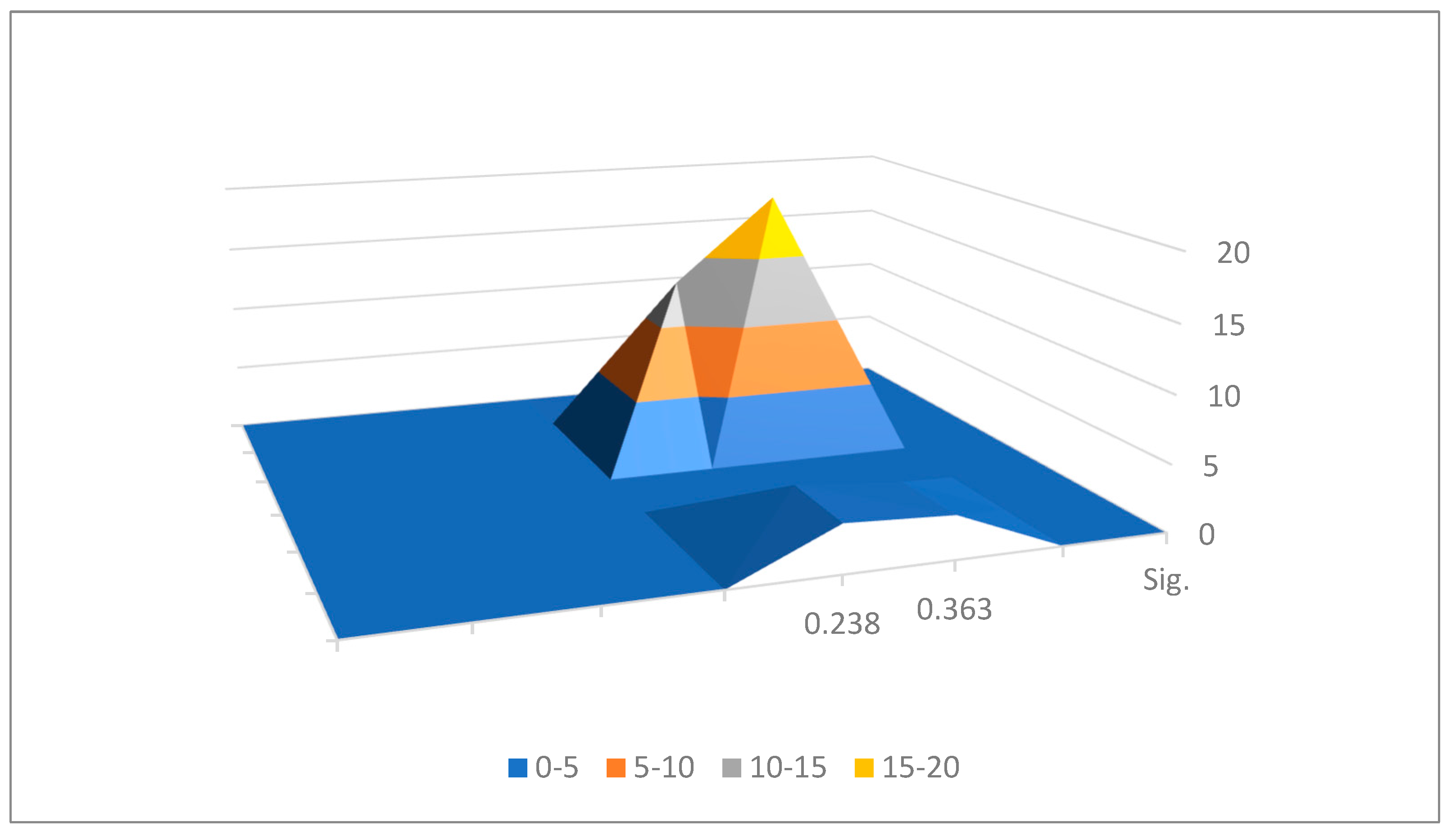

The researcher used the Kruskal–Wallis test, which is an alternative nonparametric test to the one-way ANOVA test, to test the specialization and learning method in terms of debating via Zoom.

Table 15 and

Figure 3 show that the impact of Zoom debates on students’ critical thinking and persuasive writing skills is not significantly changed by specialty, as indicated by

p-values (*Sig) above α = 0.05. Therefore, specialization did not affect students’ perceptions of the impact of Zoom debate discussions on critical thinking and evidence-based writing.

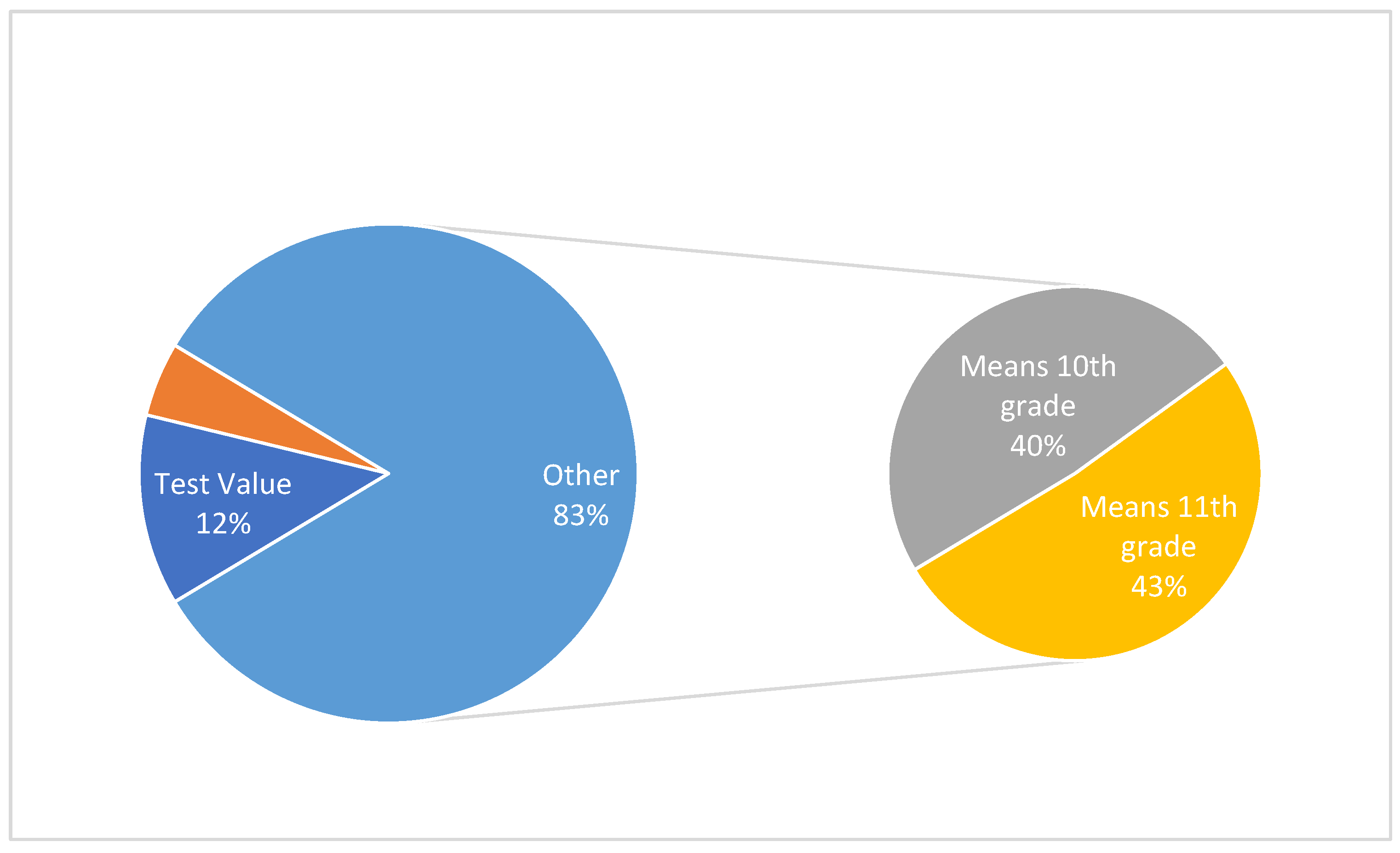

4.8. Debating via Zoom Regarding Grade

The Mann–Whitney U test was used to determine whether students’ attitudes were affected by their grades; in other words, it measures whether students’ maturity affected their attitudes regarding the debate via the Zoom teaching method.

Table 16 and

Figure 4 compare tenth and eleventh graders’ answer percentages before and after the experiment to determine if grade impacts attitudes. Post-test (Sig) values of 0.121 and above indicate no significant difference in students’ opinions of the impact of Zoom debate discussions on critical thinking and evidence-based writing skills across grades.

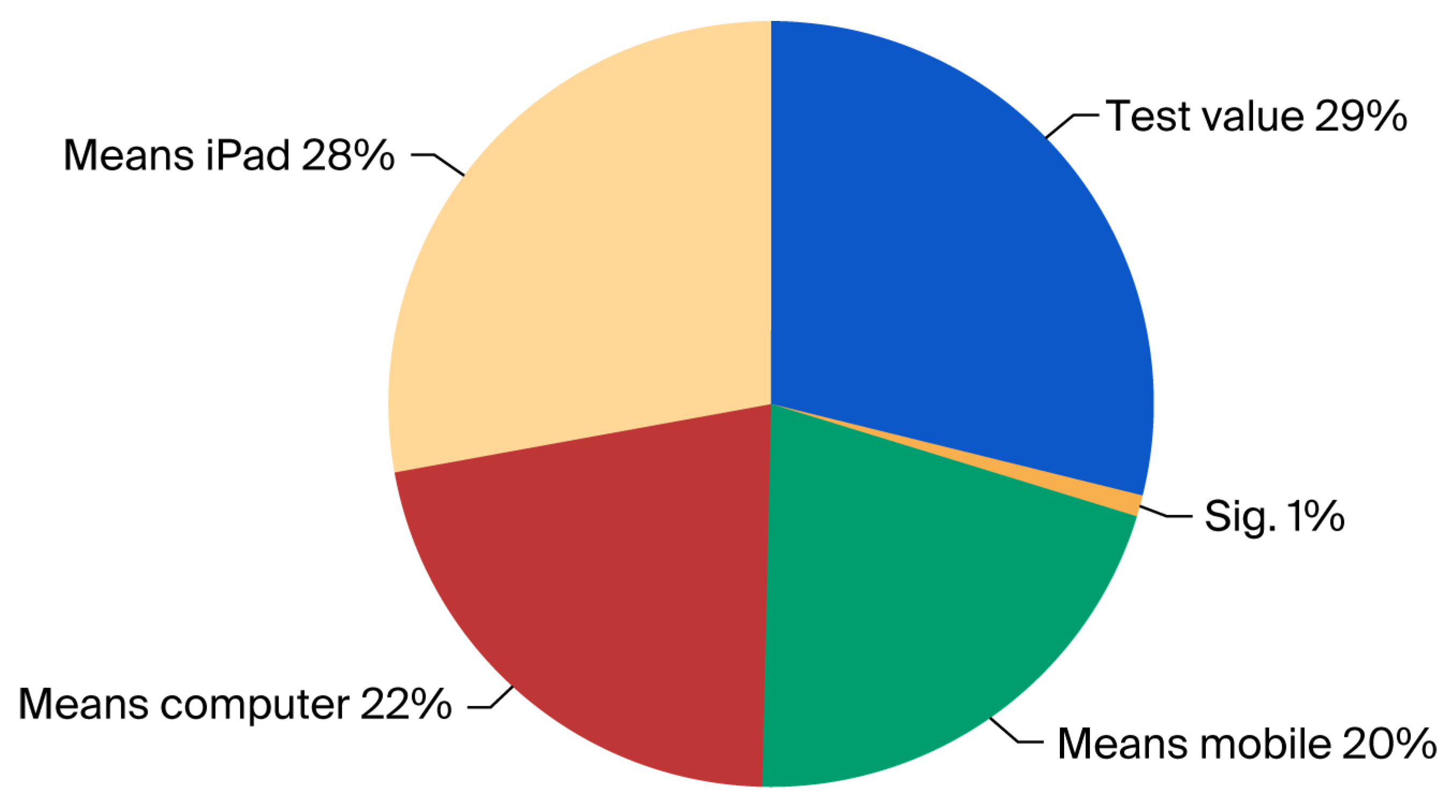

4.9. Debating via Zoom Regarding the Type of Electronic Device Used

The researcher used the Kruskal–Wallis test, an alternative to the one-way ANOVA test, to assess students’ critical thinking and evidence-based writing skills in terms of the type of electronic device used during Zoom discussions.

Results show that the mobile means were 2.94 in the pre-test, while the post-test revealed a slightly higher mean of 3.74; see

Table 17 and

Figure 5.

5. Discussion

A brief overview of the findings provided important insights into the potential effects of debate on secondary students’ learning, particularly in relation to critical thinking and evidence-based writing, addressing the first research question, “How does Zoom debate improve secondary students’ critical thinking and evidence-based writing?”

The results indicated that critical thinking subskills helped shape 10th and 11th graders’ exam scores. Debate enhances assumption, inference, evaluation, and deduction. Discussion helps reasoning, as Zoom debaters fared well in Watson and Glaser’s exercise. Researchers evaluated debaters’ and spectators’ critical thinking and online speech volume. On average, the winning team had deeper critical thinking and more speeches than teams with lower debate scores; debaters with depth of critical thinking had a negative correlation with their number of speeches; audiences’ critical thinking was not significantly correlated with the number of online posts they had; and debaters’ overall critical thinking was fourth, demonstrating that online debate enhances critical thinking.

Online learning improves students’ critical thinking skills (

Naqia & Suaidi, 2023), and e-learning and problem-solving projects improve them. Debate encourages reading, writing, and smart questioning (

Paul & Elder, 2006), thus improving critical thinking and communication.

This study found that secondary students’ performance is significant and that debate improves evidence-based writing skills. The students’ initial writing, topic identification, and argument theses were excellent. Students also add examples, figures, quotes, and elaboration to their work. According to Naqia & Suaidi, debate discussion improves students’ ability to develop arguments and details, including finding data, improving arguments, exploring references from multiple sources, recognizing problems, and finding solutions.

According to (

Jesika et al., 2021), using Zoom improves students’ speaking skills. While studying, students can open the reordered videos several times; moreover, teachers can take advantage of audio conference materials that develop students’ knowledge and double the advantages of this method. Students learn simultaneously through interactive communication with themselves and teachers, obtaining immediate feedback from teachers. This study confirmed (

Gikas & Grant, 2013) that Zoom is a flexible medium teachers can utilize anywhere and anytime (

Dhawan, 2020), adding that Zoom is a dynamic tool for student cooperation. Zoom improves learning (

Heppen et al., 2017). However, a study (

Efriana, 2021) has noted student and parent technology issues. Another study (

Cabual & Cabual, 2022) mentioned noise/environmental distractions, technological problems, and poor internet connections. In another study, the authors (

Alawamleh et al., 2020) also suggested that online learning affects instructor–student communication.

RQ2. Does Zoom debate affect students’ critical thinking and argumentation?

Students’ reflections on Zoom debates have a positive impact on enhancing critical thinking and written arguments in the high school context. Empirical evidence shows that a 59.4% response indicated that debate practice with argumentative text improved outcomes. Debate lets students assess information with rubrics (

Weeks, 2013) and links ideas (

Kuhn, 2019). Argumentation helps solve problems and express concepts. Critical thinking and written arguments need questioning, reasoning, argumentation, and explanation (

Schmidt, 1999). Zoom debate improves class focus by 58.4% (

Weeks, 2013).

Zoom debates helped 63.2% of students strengthen their evidence-based essays. Structured debate helps students learn written and oral arguments, according to a study (

Malloy et al., 2020). The study found that three-paragraph-long justifications and supplementary evidence helped students create stronger essays. Additionally, 60.4% of students thought Zoom debates improved evidence-based essay language. This study supports that arguments helped students write longer texts with higher vocabulary, grammatical precision, cohesiveness, and syntactic complexity (phrasal and clausal complexity).

Zoom did not assist boys or girls in understanding evidence-based writing. A study (

Rezaie & Sayadian, 2015) found that male and female students view technology integration in learning similarly.

Specialization did not affect students’ views on how Zoom debate discussion improves critical thinking and argumentation.

Both experimental and control students were similar before and after the experiment. Grade did not change students’ views on how Zoom debate discussion affects critical thinking and argumentation.

Laptops, phones, and iPads do not modify secondary students’ opinions about Zoom debates’ impact on critical thinking and writing.

RQ3: Are there any statistically significant differences at (α ≤ 0.05) in students’ perspectives toward social skills due to the teaching method (debating via Zoom/traditional)?

Most students (74%) felt that debates gave them courage to respond to questions. In total, 68.8% said debate lets students express themselves. Zoom debates help pupils appreciate views. Oros, 2007, SCDs teach youngsters to discuss political issues with disagreeable peers and listen to opposing ideas, which encourage citizenship, social skills, and democratic societies that defend civil rights. A total of 65% of the responses agreed that Zoom discussions improve cooperative learning among students, while a study (

Gokhale, 1995) claimed collaborative learning involves students working in groups and pairs to achieve academic goals. Small groups of pupils at different levels target a goal. The findings corroborated (

Dengler, 2008) that socially engaged virtual conversations improve class debate. Others (

Riel et al., 2022) recommended asynchronous and synchronous interactions depending on resources and opportunities to maximize social presence in educational roleplaying games and other virtual learning situations.

In total, 68.6%, 68.2%, and 66.2% of students believed Zoom debate enhanced word pronunciation and self-confidence. Also, 66.8% of students said debates improved speech.

Iranian secondary students’ speaking skills have been assessed by researchers previously (

Sukmana et al., 2023). Online discussion activities improve performance, according to classroom observations. Speech fluency and motivation also improved (

Mohammed & Ahmed, 2021).

RQ4. What is the impact of debating via Zoom platform on students’ nonverbal communication?

Zoom debates improved student communication (

Al-Mahrooqi & Tabakow, 2015;

Hassan & Madhum, 2007). In 1980, nonverbal communication-like outcomes were found (

Swain & Canale, 1982). Social media and digital tools change nonverbal communication, especially when mobility is involved. Communication encompasses verbal and nonverbal meaning-making, according to QOUT (

Kayi, 2006). Learning and using knowledge to persuade is an art, but many students lack self-confidence and fear bullying, cyberbullying, and classmate mockery. Age-related student awareness was also discovered (

Bucy & Stewart, 2018).

6. Conclusions

This study shows that Zoom debates improve secondary students’ verbal, social, and cognitive skills. Debates on Zoom improve student critical thinking. Zoomers outperformed the experimental group in terms of Watson and Glaser’s inference, assumption, and argument exercise. Internet forums may help high schoolers think critically. Zoom debates inspire students to write and argue with evidence.

This study promotes Zoom’s interactive learning. Despite technological problems, Zoom enabled students to collaborate. Research shows that interactive features like rapid feedback improve previously inaccessible online education systems. Technology limitations must be overcome, and online learning must be broadened to maximize pedagogy. Zoom debates promote student cooperation, respect, and openness. Democracy and active citizenship were promoted by virtual debates that encouraged students to speak up and argue constructively. Zoom forums foster intellectual and social growth through meaningful conversation.

Research shows that Zoom debates improve students’ pronunciation, fluency, and confidence. Online discussion activities also increase secondary students’ verbal communication, and Zoom lessons improve public speaking.

Zoom discussions improve secondary students’ critical thinking, communication, and socialization skills. Online platform affordances and problem-solving can help educators create inclusive, engaging learning environments that promote academic and social achievement. It is crucial to find creative ways to teach younger generations using virtual discussion forums.