Abstract

This study examined how young learners’ (YLs’) views of teachers’, peers’, and parents’ roles influence their motivation and task engagement in learning English, as well as their parents’ perspectives on their children’s motivation and task engagement, using a quantitative cross-sectional design. The study draws on self-determination theory, social cognitive theory, YLs’ language learning motivation, and task engagement. Data from surveys were analyzed using structural equation modeling with IBM SPSS AMOS Version 26. The sample included 598 YLs and their parents from Indonesian elementary schools. The model examines direct and indirect effects of four independent variables (YLs’ and parents’ perceptions of teachers’, peers’, and parents’ roles) on a dependent variable (task engagement) with a mediator (motivation). The model fit was adequate (Chi-Square = 67.452, CMIN/DF = 3.895, RMSEA = 0.07, RMR = 0.014, CFI = 0.934, and TLI = 0.976). Both children’s and parents’ perceptions positively influenced children’s motivation and engagement. Motivation significantly influenced task engagement and mediated the impact of children’s and parents’ views on it. The findings recommend engaging parents, encouraging peer collaboration, and training teachers to build a supportive environment for young English learners.

1. Introduction

Motivation and task engagement are important factors in young learners’ (YLs’) additional language learning. Teachers, peers, and parents are social factors (Kos, 2023; Qureshi et al., 2023) that play prominent roles in YLs’ motivation and engagement (Mihaljević Djigunović & Nikolov, 2019; Nikolov & Mihaljević Djigunović, 2019). In the Indonesian context, characterized by collective cultural values that prioritize family participation and social harmony (Deci & Ryan, 2000), comprehending the impact of these relationships on motivation and engagement is crucial for devising successful educational strategies. Earlier studies have shown that positive relationships with teachers and peers can enhance engagement in classroom activities (Gan, 2021; Li et al., 2024). Parental behaviors, including encouragement and active involvement in educational activities, can boost children’s motivation (Choi et al., 2024; Tanaka & Takeuchi, 2024).

Despite these findings, empirical evidence remains sparse regarding how these factors impact YLs’ task engagement. This study aims to address this gap by using structural equation modeling (SEM) to explore the complex interrelationships among the roles teachers, peers, and parents play in children’s motivation and task engagement in Indonesian primary schools. The study seeks to offer new insights for parents, teachers and policymakers into how fostering language learning environments can enhance student motivation and encourage persistent task engagement.

This research examines the relationships among YLs’ perceptions of the roles their teachers, parents, and peers play in their motivation to learn English in primary schools in Indonesia. Additionally, we investigate the association between parents’ perceptions of their role in shaping their children’s motivated behavior. More specifically, we attempt to determine the extent to which YLs’ motivation serves as a predictor of their task engagement in English learning. We examine whether the perceptions of YLs and their parents exert a direct influence on the children’s engagement with English tasks. Finally, we investigate YLs’ motivation as a mediator between their own and their parents’ perceptions of task engagement in learning English.

This study seeks to answer seven research questions:

- How are YLs’ perceptions of their teachers’, parents’, and peers’ roles directly associated with their motivation to learn English?

- How are parents’ perceptions of their role directly associated with YLs’ motivation to learn English?

- How does YLs’ motivation to learn English predict their engagement with English language learning tasks?

- To what extent do YLs’ perceptions of their teachers’, parents’, and peers’ roles directly predict their task engagement?

- To what extent do parents’ perceptions of their role directly predict YLs’ task engagement?

- How does YLs’ motivation to learn English mediate the relationships between their perceptions of their teachers’, parents’, and peers’ roles and their task engagement?

- How does YLs’ motivation to learn English mediate the relationships between parents’ perceptions of their role and their task engagement?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework

This study relies on two interconnected theoretical frameworks to clarify the influence of teachers, peers, and parents on young students’ motivation and task engagement: self-determination theory (SDT) and social cognitive theory. SDT highlights the importance of satisfying three essential psychological needs, relatedness, competence, and autonomy, to boost motivation and engagement (Ryan & Deci, 2020). In primary education, the encouragement and support of teachers and parents, along with the acceptance of peers, fulfill children’s need for forming relatedness. Encouragement through challenges, guidance, and feedback boosts their sense of competence. When children view their learning activities as self-driven and valued by important figures in their lives, their engagement and commitment increase, and they become gradually autonomous over time. This framework underscores how environments created by educators, family, and friends can either enhance or diminish student motivation.

SDT encompasses a range of regulation types; however, in this study we distinguish between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2020) in a way that is both deliberate and theoretically justified. Primarily, given the participants’ developmental stage, simplifying the distinction was essential for maintaining clarity and ensuring age-appropriate conceptualization.

Additionally, the study was conducted in a specific Indonesian context characterized by a collectivist cultural character (Hofstede, 2011). However, within SDT, autonomy is not synonymous with individualism, but it concerns the sense of volition (Ryan & Deci, 2020) which can exist alongside collectivist values. Therefore, we assume that autonomy-supportive techniques are compatible with interdependent cultural contexts. Although a more detailed cultural analysis could broaden the discussion, the aim of the current study was to highlight the influence of teachers, peers, and parents on motivation, rather than to offer a cross-cultural reinterpretation of SDT.

Social cognitive theory emphasizes the significance of observational learning, self-efficacy, and the reciprocal interactions between individuals and their environment (Bandura, 1986). Children tend to adopt behaviors and attitudes they observe in their teachers, parents and peers. For example, when a teacher confidently uses English in daily routines, YLs can also use English naturally. Watching enthusiastic classmates can boost learners’ confidence and motivation. Similarly, parents’ positive attitudes toward education can influence their children’s beliefs and practices. This framework shows how societal influences and personal factors shape YLs’ behavior, motivation, and engagement with tasks.

Children’s motivation is dynamic and closely linked to contextual factors (Mihaljević Djigunović & Nikolov, 2019). YLs’ motivated learning behavior interacts with their teachers’ motivation and develops based on their perceptions of their parents’, teachers’, peers’ motives, beliefs, and expectations, and other internal and external classroom factors. Moreover, the older the learner, the less influence teachers and parents have on their motivation, but the greater the influence of their peers is (Mihaljević Djigunović & Nikolov, 2019). These points are considered in the next section.

2.2. The Role of Social Factors in YLs’ Motivation and Engagement

Significant others, including teachers, peers, and parents, play a crucial role in YLs’ motivation to learn an additional language and to engagement with specific tasks (Mihaljević Djigunović & Nikolov, 2019). Learners’ attitudes and perceptions of their educators impact their level of motivation (Hiver & Al-Hoorie, 2020). A few studies have been conducted on learners’ perceptions of their teachers’ and their peers’ motivation (Tseng, 2021; Wallace & Leong, 2020), and task engagement (Lu et al., 2022). Overall, YLs’ perceptions of their teachers are positively associated with their level of motivation (Wallace & Leong, 2020). More specifically, learners’ negative perceptions of their teachers may have detrimental impacts on their motivation, as demonstrated by instances where a student expressed unfavorable opinions regarding their teacher’s literacy practices, consequently influencing their motivation to learn the English language (Tseng, 2021). Moreover, learners’ perceptions of their educators can affect their cognitive and emotional task engagement in the learning process (Lu et al., 2022). The level of involvement perceived by learners about their teachers significantly influences their engagement mediated by motivation (Núñez et al., 2019). Teachers serve crucial role models in the English learning process. Thus, teachers’ roles in the literature include being role models and engagement facilitators, and scaffolding learning. Consequently, learners’ motivation to learn English is influenced by their interactions with teachers (Liu & Chiang, 2019).

Peers also play a central role in shaping children’s motivation and task engagement. In accordance with social learning theories, observing peers exhibiting enthusiasm and perseverance can inspire similar behaviors in fellow learners (Bandura, 1986). Interaction among peers can enhance not only motivation and confidence, but it can also foster engagement in authentic communication (Bui & Dao, 2023). Additionally, it has been shown that the way YLs perceive their classmates can influence their motivation to learn English (Wallace & Leong, 2020). Not only in adult learners, but also in YLs’ classrooms, peer support can have a significant impact on learners’ motivation (Solhi, 2024) and their emotional and behavioral engagement (Ansong et al., 2017). Furthermore, some peers can serve as role models, competitors, collaborators, and help scaffold one another’s learning (Mihaljević Djigunović & Nikolov, 2019).

Parental involvement is recognized as an essential factor influencing children’s academic motivation and task engagement. It includes an array of activities, such as assisting with homework (Núñez et al., 2019), engaging in communication with teachers (Fitriani & Anam, 2024), and taking part in school-related events (Fan & Williams, 2010; Rivera & Li, 2019). Research consistently shows that when parents are actively involved, children tend to have positive attitudes toward learning and develop higher levels of persistence (Rivera & Li, 2019). Parents’ support predicts students’ task engagement (Ansong et al., 2017). Students’ perceptions of parental involvement in their homework significantly impacts their engagement with assigned tasks mediated by motivation (Núñez et al., 2019).

Parental encouragement and support can reinforce children’s motivation and task engagement. YLs’ perception of their parents’ expectations, such as to achieve a specified level in their exams, impacts their motivation. For example, Wallace and Leong (2020) found that a cultural focus on extrinsic incentives for learning with instrumental objectives may be instilled at an early age and nurtured through parental influence. Furthermore, respecting children’s learning styles, providing educational information, and offering emotional support can also enhance student motivation, whereas parental pressure for high academic outcomes may diminish intrinsic motivation (Choi et al., 2024). Multiple studies found that parents’ involvement in their children’s study of English can significantly boost their motivation (e.g., Butler, 2015; Nie & Mavrou, 2025; Sumanti & Muljani, 2021).

In summary, parental roles in children’s English learning include their ongoing involvement (Núñez et al., 2019) and expectations (Butler, 2015; Butler & Le, 2018; Wallace & Leong, 2020), and ensuring children’s access to resources, to enrichment activities (Butler, 2015; Butler & Le, 2018), and to extracurricular opportunities (Torrecilla & Hernández-Castilla, 2020).

2.3. Motivation and Task Engagement

Frameworks interpret motivation and engagement distinctively. Motivation is the force initiating, directing, and sustaining goal-oriented behaviors (Dörnyei & Ottó, 1998), whereas engagement involves the active participation reflected in behavioral, emotional, cognitive, and social aspects of learning (Philp & Duchesne, 2016). Based on SDT, motivation can be intrinsic, deriving from interest and enjoyment, or extrinsic, driven by external rewards or pressures (Ryan & Deci, 2020). YLs’ motives are sometimes driven by their parents’ expectations (e.g., they want YLs to get better grades in English). This aligns with the ought-to-self in the second language (L2) motivational self-system model (Dörnyei, 2005) which also includes rewards or positive feedback from parents and teachers. Moreover, YLs’ motivation is dynamic, it changes all the time, and it is closely linked to contextual factors (Mihaljević Djigunović & Nikolov, 2019).

Previous studies examining determinants of task engagement have highlighted how teachers, parents, peers, and motivation shape it (Dörnyei & Ushioda, 2011). Constructive relationships with educators and peers are significantly associated with cultivating autonomous motivation, including personal goals, and enhanced task engagement, both of which are critical for academic achievement. In contrast, parental relationships, although more indirect, are also influential in fostering motivation and task engagement within educational settings (Collie et al., 2016). For example, YLs who had contentious interactions with their parents and teachers showed decreased perseverance in tasks, whereas those with relationships marked by closeness and support experienced increased motivation and enhanced engagement with tasks (Silinskas & Kikas, 2022). Understanding these factors within particular cultural settings, such as Indonesia, is crucial for scaffolding the process of English language learning.

In sum, significant positive correlations were found between task engagement and motivation in studies involving children and adolescents learning EFL (Mihaljević Djigunović & Nikolov, 2019; Zhang & Crawford, 2024). Both extrinsic and intrinsic motivational factors influence YLs’ EFL learning motivation and task engagement during face-to-face English instructional sessions (Jiao, 2024). As has been discussed, multiple variables interact and impact outcomes. These are examined in a proposed model, presented in the next section.

3. Method

3.1. Research Design

This research used a quantitative cross-sectional design to investigate the relationships among factors, related to EFL teachers, parents, and peers, impacting YLs’ motivation and task engagement in Indonesian primary schools. Data was gathered at one specific moment to reflect YLs’, their teachers’, and parents’ perceptions (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). We used structural equation modeling (SEM) to evaluate the proposed model, allowing for simultaneous examination of both direct and indirect interactions among latent variables (Kline, 2023). These included YLs’ perceptions of their teachers, peers, and parents’ views as well as their parents’ perception of their role (independent variables), plus YLs’ motivation (mediator variable) and task engagement (dependent variable).

3.2. Participants

Participants included 598 fifth graders and their 598 parents at 15 public and private primary schools in Indonesia. They were chosen through a random sampling technique. We included one of the YLs’ parents; it was up to them to decide if the mother or father participated in the study. The description of participants is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of participants.

3.3. Instruments

We used two instruments for data collection. The YLs’ questionnaire (42 items) measured five latent variables: children’s perception of their teachers as role models (3 items), engagement facilitators (3 items), scaffolders (3 items); YLs’ perception of their peers as competitors (3 items) and collaborators (3 items), and their perception of parents. The latter concerned parental involvement/expectation (4 items), access to resources (4 items). Additional items comprised YLs’ motivation including intrinsic motivation (3 items), extrinsic motivation (3 items), and finally, task engagement. This part of the instrument included: behavioral (4 items), emotional (3 items), cognitive (3 items), and social (3 items).

The parents’ questionnaire comprised 19 items tapping parents’ perception of their roles across five dimensions: parental involvement (4 items), parental expectation (5 items), access to resources (5 items), enrichment activities (3 items), and extracurricular activities (2 items) (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Instrument description.

These two instruments were developed based on the literature related to the roles of teachers, peers, and parents (e.g., Fan & Williams, 2010; Mihaljević Djigunović & Nikolov, 2019; Pinter, 2017), language learning motivation (Mihaljević Djigunović & Nikolov, 2019), intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2020), and task engagement (Philp & Duchesne, 2016). They were piloted with 371 and 579 students and 270 parents of fifth graders out of this sample, confirming their validity and reliability. The model evaluating students’ perceptions demonstrated a good fit, indicated by indices (CFI = 0.996, TLI = 0.980, SRMR = 0.014, RMSEA = 0.049). Similarly, the motivation model exhibited a good fit, as evidenced by indices (CFI = 0.994, TLI = 0.989, SRMR = 0.021, RMSEA = 0.042). Moreover, the task engagement model had a good fit, it was characterized by fit indices (CFI = 0.944, TLI = 0.926, SRMR = 0.039, RMSEA = 0.079). The parents’ questionnaire indicated that the model fit was adequate (CFI = 0.945, TLI = 0.934, SRMR = 0.045, RMSEA = 0.059). The average variance extracted (AVE) values of the questionnaires exceeding 0.50 satisfy the requirements for convergent validity. Additionally, the composite reliability (CR) values exceeding 0.70 affirm the internal consistency reliability. The two questionnaires can be seen in Appendix A and Appendix B.

3.4. Data Collection Procedure

First, ethical approval was acquired from the IRB Doctoral School of Education, University of Szeged (number 24/2023). Then, signed consent forms were obtained from parents before they filled out the surveys online via Google Forms from April to June 2025. The online questionnaires were distributed to participants with the help of English teachers using WhatsApp version 2.25.22.83. All participants were informed that their involvement was voluntary, and their information was confidential.

3.5. Data Analysis

We used SEM for data analysis with IBM SPSS AMOS Version 26. The model was specified with six latent variables representing YLs’ perceptions of teachers’, peers’, and parents’ roles and their parents’ perceptions of their role, YLs’ motivation, and task engagement. All were measured through their respective indicators. Model evaluation involved assessing the measurement model for reliability and validity, including CR, AVE, and discriminant validity. Then we examined the structural model by analyzing path coefficients, and tested mediating effects to explore the complex relationships within the model; finally, we calculated squared multiple correlations (R2) for endogenous variables (motivation and task engagement).

3.6. Proposed Model

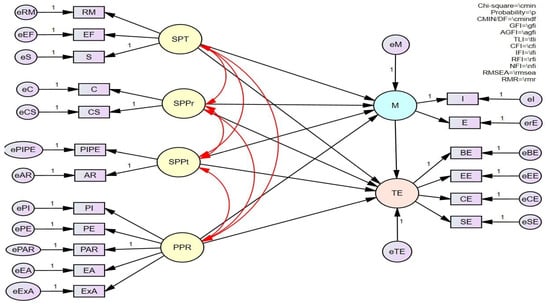

We hypothesized that the proposed model showed the relationships among YLs’ perceptions of their teachers’, parents’, and peers’ roles, their parents’ perceptions of their role, YLs’ motivation to learn English, and their task engagement. In this model, we estimated all proposed paths, including direct and indirect associations, simultaneously to capture the potential influence of each variable on YLs’ motivation and task engagement. The proposed model incorporated correlations among the exogenous latent constructs to account for shared variance across perceptions of social support (see Figure 1). Model estimation was conducted using the maximum likelihood method (Kline, 2023) in AMOS (Arbuckle, 2017). We assessed the overall fit of the proposed model using multiple fit indices to determine whether the specified paths adequately represented the observed data prior to any model specification.

Figure 1.

Proposed model of perceptions, motivation, and task engagement. Note: students’ (YLs) perception of teachers (SPT): role model (RM), engagement facilitator (EF), scaffolding (S); students’ (YLs) perception of peers (SPPr): competitor (C), collaborator/scaffolding (C/S); students’ (YLs) perception of parents (SPPt): parental involvement and expectation (PI/PE), access to resources (AR); parents’ perception of their role (PPR): parental involvement (PI), parental expectation (PE), access to resources (PAR), enrichment activities (EA), extracurricular activity (ExA); motivation (M): intrinsic (I), extrinsic (E); task engagement (TE): behavioral engagement (BE), emotional engagement (EE), cognitive engagement (CE), social engagement (SE).

4. Results

4.1. Prerequisite Analysis

Prior to executing the primary data analysis, we conducted a normality test and a multicollinearity test (Hair et al., 2018; Kline, 2023). An examination of normality reveals that, on a univariate level, each measurement indicator within this study adheres to a normal distribution, as indicated by the critical ratio value being less than 2.58 or exceeding −2.58. Furthermore, from a multivariate perspective, the critical ratio value of 1.947, which is below the threshold of 2.58, further confirms that the data conforms to a normal distribution (Hair et al., 2018; Kline, 2023).

Inner model multicollinearity can be seen based on the correlation value between exogenous variables. Table 3 presents the correlations among the latent constructs. Motivation (M) shows a strong correlation with YLs’ perception of peers (SPPr) (0.689), YLs’ perception of teachers (SPT) (632), YLs’ perception of parents (SPPt) (0.602), and parents’ perception of their role (PPR) (0.578), highlighting its pivotal position in the model. Task engagement (TE) correlates strongly with motivation (M) (r = 0.672) and maintains moderate connections with YLs’ perception of teachers (SPT) (0.321), parents’ perception of their role (PPR) (0.297), YLs’ views of parents (SPPt) (0.406), and YLs’ perception of peers (SPPr) (0.407). A strong correlation exists between YLs’ views of peers (SPPr) and YLs’ perception of teachers (SPT) (0.577), and a substantial relationship is also observed between children’s perception of parents (SPPt) and of peers (SPPr) (r = 0.596). In contrast, parents’ perception of their role (PPR) exhibits relatively weaker correlations with YLs’ perception of teachers (SPT) (r = 0.209), parents (SPPt) (0.208), and peers (SPPr) (0.238).

Table 3.

Correlation matrix for inner model.

Overall, these results indicate that motivation is the most interconnected construct, whereas parents’ self-perception shows a weaker alignment with YLs’ perspectives on their educational setting. The results showed that no correlation between exogenous latent constructs is greater than 0.9 or lower than −0.9; therefore, in this model, there is no multicollinearity at the latent construct level or inner model level (Kline, 2023).

Outer model multicollinearity can be seen based on the correlation value between indicators, especially between exogenous variable indicators. Table 4 presents the correlations among the indicator levels. For example, motivation indicators, extrinsic (E) and intrinsic (I), had a strong correlation (0.782). Parents’ perception of their role indicator, such as extracurricular activities (ExA) had a very weak correlation with most indicators. However, the results indicated that no correlation between indicators is higher than 0.9 or lower than −0.9; therefore, there is no multicollinearity at the indicator level or outer model level (Kline, 2023). This implies that the indicators were adequately distinct, and none had high correlation to cause estimation or identification issues within the SEM.

Table 4.

Correlation matrix for outer model.

4.2. Measurement Model Assessment

In the assessment of the measurement model, we evaluated systematically the validity and reliability using factor loadings, composite reliability and average variance extracted. Furthermore, we examined the model for potential Heywood cases (Byrne, 2013; Kline, 2023) and analyzed the correlations among latent variables to evaluate discriminant validity.

Table 5 presents the AVE and CR values for each construct, signifying that the measurement model demonstrates acceptable convergent validity and internal consistency reliability. All constructs exhibit AVE values above the suggested cutoff of 0.50, indicating that over 50% of the variance in the indicators is accounted for by the latent constructs rather than error (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). For instance, the YLs’ perception of peers (SPPr) AVE value stood at 0.595, indicating that a significant 59.5% of the variance in the observed variables was explained by the latent construct, thus demonstrating strong convergent validity. Conversely, the parents’ perception of their role (PPR) showed a lower AVE value of 0.516, suggesting that while it maintains adequate convergent validity, its indicators represent the construct with slightly less intensity compared to constructs associated with higher AVE values. Furthermore, all CR values exceed the minimum recommended cutoff of 0.70, indicating adequate reliability and internal consistency (Hair et al., 2018).

Table 5.

The AVE and CR values of constructs.

In summary, these outcomes confirm that YLs’ perceptions of their teachers’ role (SPT), parents’ role (SPPt), peers’ role (SPPr), as well as their parents’ perceptions of their role (PPR), and motivation (M), and task engagement (TE) were assessed both reliably and validly.

Table 6 provides information about variances. We found no indicators with latent constructs that have negative variance values; therefore, there is no Heywood case problem (Kline, 2023). The error terms (e.g., eRM = 0.199, ePE = 0.168, eAR = 0.156) are well within acceptable ranges, while the critical ratios remain high (c.r. > 1.96), supporting the estimates’ stability. Consequently, although certain predictors, such as SPPt (0.199) and PPR (0.146), exhibit notably significant contributions, the model contains no improper estimates and is statistically robust, free from the concerns of Heywood cases.

Table 6.

Variances.

Table 7 presents the correlations among latent variables. They showed significant positive relationships, indicating meaningful associations between parents’ perceptions (PPR), and YLs’ perceptions of parents (SPPt), teachers (SPT), and peers (SPPr). For example, students’ perceptions of their teachers’ (SPT) and peers’ role (SPPr) were strongly correlated (r = 0.577, p < 0.001), supporting the interconnected influence of these social factors on YLs’ motivation and engagement.

Table 7.

Correlations among latent variables.

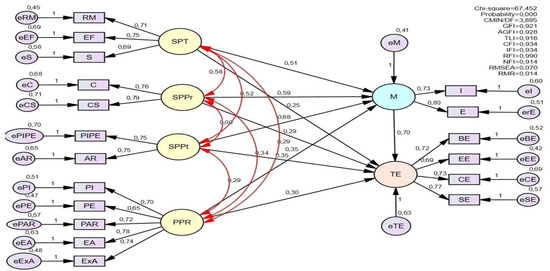

4.3. Goodness of Fit

The model exhibited an overall satisfactory fit, as evidenced by a Chi-Square value of 67.452 (with a p-value indicative of fit) and a CMIN/DF of 3.895, both of which reside within the acceptable range (Schumacker & Lomax, 2010). The RMSEA was reported at 0.07 and the RMR at 0.014, both indices suggesting an adequate model fit. Furthermore, the goodness-of-fit indices supported this inference, with CFI = 0.934 and TLI = 0.976, each exceeding the commonly recommended thresholds (Hu & Bentler, 1999), thus indicating that the model effectively represents the observed data. In other words, the model fit the data very well.

4.4. Path Analysis

4.4.1. Direct Effect

YLs’ motivation (M) is significantly influenced by various factors, according to the direct effect results. Specifically, YLs’ perceptions of their teachers’ (SPT), parents’ (SPPt), and peers’ roles (SPPr), and parents’ perceptions of their roles (PPR) positively impact YLs motivation to learn English (M). Among these, YLs’ perceptions of their parents’ roles (SPPt) exhibits the strongest impact (0.676), and parents’ perceptions of their roles (PPR) has the lowest impact (see Table 8). Furthermore, task engagement (TE) is also strongly affected by these variables. Positive associations are observed between task engagement (TE) and YLs’ perceptions of teachers’ (SPT), peers’ (SPPr), and parents’ roles (SPPt), and parents’ perceptions of their roles (PPR). YLs’ perceptions of parents’ role (SPPt) had the strongest impact on task engagement (TE) among others (0.352), indicating a moderate impact, and YLs’ perceptions of teachers’ roles (SPT) had the weakest impact on task engagement (TE) (0.246), indicating a small to moderate impact (Hair et al., 2018; Kline, 2023). Importantly, motivation (M) is a strong predictor of task engagement (TE) (0.696) (Kline, 2023), indicating that YLs’ motivation is vital in task engagement. All noted effects are statistically significant and indicate strong interconnections among these variables as p < 0.001, indicating significant, p = 0.004, and p = 0.009, very significant.

Table 8.

Direct effect.

4.4.2. Indirect Effect

The results relating to indirect effects demonstrate that YLs’ perceptions of their teachers’ (SPT), parents’ (SPPt), and peers’ role (SPPr), and their parents’ perceptions of their role (PPR) significantly predict YLs’ task engagement (TE) through the mediation of their English learning motivation (M). As seen in Table 9, the most significant and strong indirect effect originates from SPPt influencing task engagement (0.471), followed sequentially by YLs’ perceptions of peers’ role (SPPr) (0.406), YLs’ perceptions of their teachers’ role (SPT) (0.354, p = 0.004), and parents’ perceptions of their role (PPR) (0.240). Each pathway corresponds with statistically significant p-values less than 0.01. They indicate robust mediation. These perceptions predominantly exert a positive influence on task engagement by enhancing YLs’ motivation to learn English.

Table 9.

Indirect effect.

4.4.3. Total Effect

Table 10 illustrates the total effects presented in the model. For example, YLs’ perceptions of their teachers’ role (SPT) has a small to moderate direct effect on task engagement (TE) (0.246) and a moderate indirect effect via motivation (0.354), resulting in a large total effect (0.600), as 0.600 > 0.50 is considered large (Hair et al., 2018; Kline, 2023). This outcome means that when the SPT increases by one standard deviation, task engagement (TE) is expected to increase by 0.600 standard deviation. The results demonstrate that each predictor, YLs’ perceptions of teachers’ (SPT), peers’ (SPPr), and parents’ roles (SPPt), and parents’ perceptions of their role (PPR), exerts a significant influence on task engagement both directly and indirectly through motivation as a mediator, thereby underscoring the critical role of motivation in the pathway to task engagement.

Table 10.

Total effect of the model.

4.5. Squared Multiple Correlations (R2)

Table 11 illustrates the squared multiple correlations (R2) in the model, highlighting that a significant portion of the variance in the endogenous variables is explained by the predictors. For YLs’ motivation (M), the R2 value is 0.697 (p < 0.001), showing that around 69.7% of the variance in YLs’ motivation is explained by its predictors: YLs’ perceptions of teachers’ (SPT), peers’ (SPPr), and parents’ role (SPPt), and parents’ perceptions of their role (PPR). Task engagement (TE) has an even higher R2 value of 0.826 (p < 0.001), signifying that the model accounts for 82.6% of the variance in task engagement. Task engagement (TE) is directly influenced by YLs’ perceptions of teachers’ (SPT), peers’ (SPPr), and parents’ roles (SPPt), and parents’ perceptions of their role (PPR) and indirectly influenced through motivation (M). These high R2 values indicate that the model has strong explanatory power both in motivation and in task engagement (Kline, 2023).

Table 11.

R2 values for endogenous constructs.

4.6. Final Model

Figure 2 illustrates the final SEM model of the relationships among YLs’ perceptions of their teachers’, parents’, and peers’ roles, their parents’ perceptions of their role, YLs’ motivation to learn English, and their task engagement at 15 Indonesian primary schools. The SEM technique facilitates the concurrent examination of both direct effects of YLs’ and parents’ perception of roles in their children’s motivation and task engagement, as well as indirect effects of YLs’ and parents’ perceptions of their impact on task engagements via YLs’ motivation, thus offering a holistic insight of the manner in which these social perceptions impact YLs’ motivation and task engagement in English language education. The final model was evaluated through the utilization of various fit indices to ensure its precise representation of the dataset.

Figure 2.

Final SEM of perceptions, motivation, and task engagement estimated in AMOS.

In summary, both YLs’ and parents’ perceptions influenced the children’s motivation and task engagement. YLs’ motivation influenced their task engagement and their perceptions influenced task engagement via their motivation. Moreover, parents’ perceptions also influenced task engagement via YLs’ motivation.

5. Discussion

Based on the results of the analysis, the model fit was satisfactory: Chi-Square = 67.452, CMIN/DF = 3.895, RMSEA = 0.07, and RMR = 0.014. CFI = 0.934 and TLI = 0.976 exceeded recommended thresholds, confirming the model’s effectiveness. Therefore, this model can be used to examine children’s and parents’ perceptions of motivation and task engagement, especially at the elementary school level. According to this model, task engagement is influenced by children’s and parents’ perceptions and YLs’ motivation. The effect of the YLs’ and parents’ perceptions on task engagement is also mediated by motivation. Enhancing task engagement involves more than just addressing motivation. It is crucial to account for how students and parents view their roles, as these perspectives significantly impact both motivation and task engagement.

All constructs have AVE values above 0.50, showing that indicators’ variance is mainly due to the latent construct (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). CR values exceed 0.70, indicating reliability and consistency (Hair et al., 2018). These outcomes validate the reliable and valid measurement of YLs’ perceptions of their teachers’, parents’, and peers’ roles, as well as parents’ self-perception of their own roles, and YLs’ motivation and task engagement.

Regarding research question 1, YLs’ perceptions of their teachers’, parents’, and peers’ roles all positively impact motivation. This is in line with the framework Mihaljević Djigunović and Nikolov’s (2019) proposed for YLs’ language learning motivation. YLs’ perception of their teachers and peers had a significant and strong impact on their motivation (0.509 and 0.583, respectively) (Hair et al., 2018; Kline, 2023). These results also align with the study conducted by Wallace and Leong (2020) that showed that YLs’ perceptions of their teachers are positively associated with their levels of motivation. Moreover, YLs’ classmates also influence their motivation to learn English (Wallace & Leong, 2020). This result is in harmony with findings that peer support has a significant influence on learners’ motivation (Solhi, 2024) and the interaction among peers enhances learners’ motivation (Bui & Dao, 2023).

Furthermore, YLs’ perceptions of their parents’ role had the strongest impact on their motivation (0.676), suggesting that YLs’ motivation to learn English significantly increases when they experience high levels of parental support and involvement. YLs’ perception of their teachers and peers impact also had a significant and strong impact on their motivation (0.509 and 0.583, respectively) (Hair et al., 2018; Kline, 2023). This result supports the claim made by Mihaljević Djigunović and Nikolov’s (2019) that as learners age, their motivation is less impacted by teachers and more importantly shaped by their peers.

As far as research question 2 is concerned, parents’ perceptions of their roles positively impact YLs’ EFL learning motivation. Parents’ perceptions of their roles had a moderate impact on YLs’ motivation; however, this is the lowest among the relationships (0.346) (Hair et al., 2018; Kline, 2023). Again, this further supports the point (Mihaljević Djigunović & Nikolov, 2019) assertion peers’ impact increases as learners age. The result is also in line with a previous study on parental involvement in children’s learning. The more parents are concerned with how their children progress, the more likely they are to develop positive attitudes toward learning and higher levels of persistence (Rivera & Li, 2019).

As for research question 3, motivation emerged as a significant influence on task engagement (0.696); this means that the more children are motivated to learn English, the more they tend to engage with tasks in their English classes. This result supports a previous study indicating that motivation influenced how much children engaged in learning English actively (Jiao, 2024).

Regarding research question 4, YLs’ perceptions of their teachers’, parents’, and peers’ roles all positively impacted YLs’ task engagement. YLs’ perception of their parents had the strongest impact among them (0.352), and YLs’ perception of peers’ role had a weak impact (0.284) and teachers’ role exerted the weakest impact (0.246). These results align with previous studies that revealed that parents’ and peers’ support predicts learners’ engagement (Ansong et al., 2017). If children are aware of their parents’ high expectations, positive attitudes, interest, and active involvement in their English learning, these give their actions direction to do more tasks and more often to improve their English. The interaction among peers contributes to fostering students’ engagement (Bui & Dao, 2023).

In response to research question 5, we found that parents’ views of their role positively impacted their children’s task engagement. Parents’ perceptions of their role had a weak impact on task engagement (0.297), indicating a small to moderate impact (Hair et al., 2018; Kline, 2023). Our study highlighted that parental perception of their role is important, but their impact is relatively weak. Overall, although parents’ involvement influences YLs’ motivation (Butler, 2015; Nie & Mavrou, 2025), and parental engagement in children’s English learning contributes significantly to their motivation (Sumanti & Muljani, 2021), these relationships are less impactful.

As for the results concerning research question 6, the results showed that motivation mediated the impact of YLs’ perceptions of teachers’, parents’, and peers’ roles on YLs’ task engagement. YLs’ perceptions of parents’ role had the most significant and moderate indirect effect on task engagement (0.471), followed by YLs’ perceptions of teachers’ role had a significant moderate indirect effect on task engagement (0.345). This aligns with a previous study where motivation mediated the relationship between perceived teacher support and engagement (Yang & Du, 2023). Motivation acts as a mediator in the connection between how students perceive their parents’ and teachers’ involvement in homework and their own engagement with it (Núñez et al., 2019). Each pathway had a significant p-value less than 0.01, signifying strong mediation. These perceptions primarily have a positive effect on task engagement by increasing YLs’ motivation to learn English. The results highlight the essential role of motivation plays in promoting task engagement.

Results related to research question 7 showed that motivation mediated the impact of parents’ perceptions of their role on YLs’ task engagement. Parents’ perceptions of their roles had the lowest and a small to moderate indirect effect on task engagement (0.240), but this interaction indicates strong mediation. Parents’ perceptions primarily have a positive effect on task engagement by increasing their children’s motivation to learn English.

The model’s total effects showed that each predictor, namely YLs’ perceptions of teachers’, peers’, and parents’ roles, and parents’ perceptions of their role, significantly influences task engagement, both directly and indirectly, with motivation as a mediator. As an example, YLs’ perceptions of their teachers have a direct effect on task engagement of 0.246 and an indirect effect through motivation of 0.354, totaling 0.600, indicating a large effect (Hair et al., 2018; Kline, 2023). This result confirmed outcome of a previous study claiming that the perception of teachers influenced engagement via motivation (Yang & Du, 2023).

Motivation has an R2 of 0.697 (p < 0.001), meaning 69.7% of motivation is explained by YLs’ perception of their teachers’, parents’, and peers’ roles as well as parents’ views of their roles. Task engagement’s R2 is 0.826 (p < 0.001), with 82.6% of task engagement explained by the same predictors, plus an indirect influence through motivation. These R2 values show strong explanatory power in motivation and task engagement (Kline, 2023).

6. Conclusions and Implications

We found that YLs’ and parents’ perceptions of various stakeholders’ roles positively impact children’s EFL learning motivation and task engagement. Motivation significantly influenced task engagement and mediated the impact of YLs’ and parents’ perceptions on it.

This study offers insights into the ways in which SEM can analyze complex relationships between social influences (teachers, peers, parents) and psychological outcomes (motivation, task engagement) in the case of young learners of English in Indonesian primary schools. By integrating survey data from 15 schools and validating the model through reliability and validity checks, this research offers a model for future studies on social and motivational factors in English language learning, especially at the primary school level. It also highlights the need to assess both direct and indirect effects to fully understand contextual variables such as school characteristics, teacher and peer support, and family background.

These findings offer strong evidence that teacher, peer, and parent support can significantly boost YLs’ motivation to learn English and to engage with tasks. These results imply what schools should consider implementing strategies like parent involvement, peer collaboration, and teacher training on motivation to foster a supportive environment. The findings help us understand social influences on motivation, showing how context affects young learners’ motivation to learn English and to work on tasks scaffolding learning.

7. Limitation

This study’s focus on fifth-grade students in a specific educational context limits its generalizability. Self-reported surveys may be biased due to social desirability or participants’ self-awareness. The cross-sectional design restricts causal inference about influences on YLs’ motivation and engagement. Although SEM provides a robust analysis, it depends on model fit and observed variables, possibly missing complex motivational processes.

Future research should broaden the study and involve YLs from various grades and educational environments to improve the findings’ generalizability. Longitudinal studies are advised to explore the impact of teachers, peers, and parents on motivation and task engagement over time. Also, using interviews, classroom observations, and teacher reflections could offer deeper triangulation of insights into the dynamics of language learning motivation and task engagement.

Author Contributions

M.S.L.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Methodology, Visualization; M.N.: Supervision, Writing—review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the University of Szeged Open Access Fund. Grant ID: 8067.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Doctoral School of Education, University of Szeged (protocol code 24/2023 and date of approval: 21 December 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The participants were all adults, and their participation was entirely voluntary.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants who contributed to this study. The first author is a Stipendium Hungaricum Scholarship grantee at the University of Szeged. We want to thank Universitas Negeri Padang for financial support toward the APC of this article, funded by the Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP) on behalf of the Indonesian Ministry of Higher Education, Science and Technology, and managed under the EQUITY Program (Contract No. 4310/B3/DT.03.08/2025 and 2692/UN35/KS/2025).

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest in this study.

Appendix A

Students’ perception of teachers’, peers’, and parents’ roles

Students’ perception of teachers

Role model

My teacher…

- 1.

- uses fluent English in our classes.

- 2.

- is easy to understand.

- 3.

- encourages me to use English.

Engagement facilitator

In the English classes, …

- 4.

- I like the games.

- 5.

- I enjoy role-play activities.

- 6.

- Group work is fun.

Scaffolding

In the English classes, …

- 7.

- tasks are often challenging for me.

- 8.

- we do easy tasks before difficult ones.

- 9.

- my teacher often gives me positive feedback.

Students’ perception of peers

Competitor

- 10.

- I want to speak fluent English like my friends.

- 11.

- I always do my best to get a better grade than my friends.

- 12.

- I want to do my tasks faster than my friends.

Collaborator/Scaffolding?

- 13.

- I enjoy working on tasks with my friends.

- 14.

- When I get stuck, I ask my friends for help.

- 15.

- My friends help me when I find something difficult.

Students’ perception of parents

Parental involvement and expectation

My parents…

- 16.

- are interested in my progress in English.

- 17.

- help me with my English tasks.

- 18.

- want me to practice English outside of school.

- 19.

- encourage me to study English hard.

Access to resources

- 20.

- I have English books at home.

- 21.

- I often access videos at home in English.

- 22.

- I often play games in English.

- 23.

- I go to extra English classes.

Motivation

Extrinsic

- 24.

- My parents think it is important for me to know English.

- 25.

- I feel proud when my teacher says I am good at English

- 26.

- I want to do well in English to get rewards from my parents

Intrinsic

- 27.

- I enjoy learning English a lot.

- 28.

- I like to use my English in my free time.

- 29.

- I use English for fun activities.

Task engagement

Behavioral

- 30.

- I always do my best when we practice speaking.

- 31.

- I focus when doing listening tasks.

- 32.

- I focus on spelling and grammar when I write in English.

- 33.

- I work hard on reading tasks.

Cognitive

- 34.

- I organize my ideas clearly when I write in English.

- 35.

- I guess the meaning of new words while reading in English.

- 36.

- I try to express my idea in English.

Social

- 37.

- I help my friends with English tasks

- 38.

- I listen closely when my friends share their English tasks.

- 39.

- I work with my friends to make my English writing better.

Emotional

- 40.

- I enjoy storytelling tasks.

- 41.

- I like to fill in blanks in tasks.

- 42.

- I enjoy getting feedback on my writing from my teachers.

Appendix B

Parents’ perception of their role

Parental involvement

- 1.

- I ask the teacher regularly about my child’s progress in English.

- 2.

- I help my child with the English tasks at home.

- 3.

- I read English storybooks with my child.

- 4.

- I attend parental meetings with my child’s English teacher.

Parental expectation

- 5.

- It is important for my child to be good at English.

- 6.

- I expect my child to do well in their English lessons.

- 7.

- I expect my child to get a good grade in English lessons.

- 8.

- I want my child to speak English fluently.

- 9.

- I want my child to enjoy learning English.

Access to resources

- 10.

- I provide English books for my child to learn English at home.

- 11.

- I provide my child with access to the Internet and to videos in English.

- 12.

- I provide access to games in English.

- 13.

- My child has access to English language apps.

- 14.

- My child can watch movies in English at home

Enrichment activities

- 15.

- My child reads English storybooks at home.

- 16.

- My child learns English at a language center

- 17.

- I pay for private tutoring in English.

Extracurricular activities

- 18.

- I encourage my child to participate in activities in English outside school.

- 19.

- I support my child to participate in an English competition such as “spelling bee”.

References

- Ansong, D., Okumu, M., Bowen, G. L., Walker, A. M., & Eisensmith, S. R. (2017). The role of parent, classmate, and teacher support in student engagement: Evidence from Ghana. International Journal of Educational Development, 54, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, J. L. (2017). IBM SPSS Amos 25 user’s guide. Amos Development Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, T. L. D., & Dao, P. (2023). Primary school children’s peer interaction: Exploring EFL teachers’ perceptions and practices. Language Teaching Research, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Y. G. (2015). Parental factors in children’s motivation for learning English: A case in China. Research Papers in Education, 30(2), 164–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Y. G., & Le, V. N. (2018). A longitudinal investigation of parental social-economic status (SES) and young students’ learning of English as a foreign language. System, 73, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. M. (2013). Structural equation modeling with AMOS (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, N., Jung, S., & No, B. (2024). Learning a foreign language under the influence of parents: Parental involvement and children’s English learning motivational profiles. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 33(1), 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, R. J., Martin, A. J., Papworth, B., & Ginns, P. (2016). Students’ interpersonal relationships, personal best (PB) goals, and academic engagement. Learning and Individual Differences, 45, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The psychology of the language Learner: Individual differences in second language acquisition. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Dörnyei, Z., & Ottó, S. (1998). Motivation in action: A process model of L2 motivation. Working Papers in Applied Linguistics, 4, 43–69. Available online: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/39/ (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2011). Teaching and researching motivation (2nd ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, W., & Williams, C. M. (2010). The effects of parental involvement on students’ academic self-efficacy, engagement and intrinsic motivation. Educational Psychology, 30(1), 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitriani, A., & Anam, K. (2024). Parental involvement in young learners’ speaking: A qualitative study on learner performance and classroom instruction. JOLLT Journal of Languages and Language Teaching, 12(4), 1705–1720. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, S. (2021). The role of teacher-student relatedness and teachers’ engagement on students’ engagement in EFL classrooms. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2018). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage. [Google Scholar]

- Hiver, P., & Al-Hoorie, A. H. (2020). Reexamining the role of vision in second language motivation: A preregistered conceptual replication of You, Dörnyei, and Csizér (2016). Language Learning, 70(1), 48–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z. (2024). Motivations for primary school students in EFL countries to participate during in-person English sessions. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media, 39(1), 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kos, T. (2023). Exploring peer support among young learners during regular EFL classroom lessons. International Journal of Applied Linguistics (United Kingdom), 33(2), 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T., Wang, Z., Merrin, G. J., Wan, S., Bi, K., Quintero, M., & Song, S. (2024). The joint operations of teacher-student and peer relationships on classroom engagement among low-achieving elementary students: A longitudinal multilevel study. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 77, 102258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R., & Chiang, Y. L. (2019). Who is more motivated to learn? The roles of family background and teacher-student interaction in motivating student learning. Journal of Chinese Sociology, 6(1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G., Xie, K., & Liu, Q. (2022). What influences student situational engagement in smart classrooms: Perception of the learning environment and students’ motivation. British Journal of Educational Technology, 53, 1665–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaljević Djigunović, J., & Nikolov, M. (2019). Motivation of young learners of foreign languages. In M. Lamb, K. Csizér, A. Henry, & S. Ryan (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of motivation for language learning (pp. 515–533). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, D., & Mavrou, I. (2025). Parents’ views on Chinese young learners’ foreign language learning attitudes and motivation: A mixed methods study. Language Teaching, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolov, M., & Mihaljević Djigunović, J. (2019). Teaching young language learners. In X. Gao (Ed.), Second handbook of English language teaching (pp. 577–599). Springer International. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, J. C., Regueiro, B., Suárez, N., Piñeiro, I., Rodicio, M. L., & Valle, A. (2019). Student perception of teacher and parent involvement in homework and student engagement: The mediating role of motivation. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philp, J., & Duchesne, S. (2016). Exploring engagement in tasks in the language classroom. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 36, 50–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinter, A. (2017). Teaching young language learners (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, M. A., Khaskheli, A., Qureshi, J. A., Raza, S. A., & Yousufi, S. Q. (2023). Factors affecting students’ learning performance through collaborative learning and engagement. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(4), 2371–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, H., & Li, J. T. (2019). Hispanic parents’ involvement and teachers’ empowerment as pathways to Hispanic English learners’ academic performance. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 41(2), 214–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (2010). A beginner’s guide to structural equation (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Silinskas, G., & Kikas, E. (2022). Patterns of children’s relationships with parents and teachers in grade 1: Links to task persistence and performance. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 836472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solhi, M. (2024). Do L2 teacher support and peer support predict L2 speaking motivation in online classes? The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 33(4), 829–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumanti, C. T., & Muljani, R. (2021). Parents’ involvement and its effects on English young learners’ self-efficacy. Celtic: A Journal of Culture, 8(1), 78–89. Available online: https://ejournal.umm.ac.id/index.php/celtic/article/view/14632 (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Tanaka, S., & Takeuchi, O. (2024). Sociocultural influences on young Japanese English learners: The impact of parents’ beliefs on learning motivation. Journal for the Psychology of Language Learning, 6(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrecilla, F. J. M., & Hernández-Castilla, R. (2020). Does parental involvement matter in children’s performance? A Latin American primary school study. Revista de Psicodidáctica (English Ed.), 25(1), 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y. H. (2021). Exploring motivation in EFL learning: A case study of elementary students in a rural area. Taiwan Journal of TESOL, 18(2), 93–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, M. P., & Leong, E. I. L. (2020). Exploring language learning motivation among primary EFL learners. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 11(2), 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., & Du, C. (2023). The predictive effect of perceived teacher support on college EFL learners’ online learning engagement: Autonomous and controlled motivation as mediators. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 46(7), 1890–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., & Crawford, J. (2024). EFL learners’ motivation in a gamified formative assessment: The case of quizizz. Education and Information Technologies, 29(5), 6217–6239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).