Abstract

Significant time, money, and energy are invested in Continuing Professional Development (CPD) across Further Education (FE) colleges in England, with the aim of enhancing teaching strategies, sharing “best” practices, and improving educational quality. Despite these intentions, practitioner perceptions of CPD’s value remain mixed, highlighting concerns about the effectiveness of current approaches. CPD managers often face competing financial and operational demands, alongside pressure to comply with external requirements, resulting in CPD that is frequently instrumental, mandatory, and delivered through one-off events. These practices reflect a data-driven, prescriptive management culture that prioritizes measurable outcomes over meaningful educational experiences. Consequently, teachers are compelled to demonstrate compliance within a system where accountability is unevenly distributed. This medium-scale, multi-method practitioner research study investigates how such compliance-driven CPD practices divert attention and resources from genuine educational improvement. This study explores an alternative model of CPD rooted in teacher agency and enriched through engagement with the arts and aesthetic experiences. Drawing on surveys, semi-structured interviews, critical incidents, and narrative accounts, the findings suggest that this approach fosters more democratic, creative, and impactful professional development. In promoting teacher agency and challenging dominant power structures, this study offers a vision of CPD that supports meaningful educational transformation, with practical examples and recommendations for broader implementation.

1. Introduction

1.1. Context

Issues in approaches to the initial and continuing professional development of educators dominate debates and discourses related to improving teaching quality and student outcomes. Continuing Professional Development (CPD) plays a significant role in this process, with schools and colleges dedicating substantial amounts of time and scarce resources to CPD “initiatives”. However, the expectation that school and college staff will not only participate but also enhance their practice through CPD experiences raises important questions about its effectiveness. While CPD generally aims to promote effective teaching strategies, share best practices, and enhance the overall quality of educational provision, the value placed on these initiatives by practitioners varies significantly. This indicates that conventional approaches, often in the form of CPD “events”, may be in urgent need of review.

Across all levels of education, differentiation, or more recently “personalized learning” or “adaptive teaching”, is frequently emphasized. Teachers are encouraged to adjust their methods to meet the diverse needs of learners. Paradoxically, a similar imperative is often absent from CPD for teachers, which tends to rely on standardized, “off-the-shelf” solutions which have often seldom been subjected to peer review and systematic and rigorous empirical evaluation (Taylor, 2017). Such “one-size-fits-all” approaches fail to consider the importance of the unique contexts in which educators operate. Theories and concepts which lay claim to “effective” education almost always require adaptation and implementation by teachers in their own specific contexts and environments, a process that is rarely, if ever, straightforward. Mastering any craft involves iterative problem finding, problem solving, critique, and subsequent further adaptation. The same principles are equally applicable to teaching (Sennett, 2008). CPD that fails to take local knowledge and context seriously is likely to be doomed to predictable failure from the start (Sarason, 1990). In addition, approaches to CPD which do not ignite the imaginations of teachers or spark teachers’ engagement in aesthetic experience and cultural change, are unlikely to subsequently be put to work by teachers in capturing the imaginations of their learners (Dewey, 1934). In this way, the personal, reflective, and emotional aspects of professional learning may fall short of inspiring deeper teacher–learner engagement or sustainable change in educational practice.

The development of educational practice is not a purely technical endeavor; it is also an experiential one, involving a clear sense of purpose, mutual engagement in a shared endeavor, imagination, creativity, and professional fulfilment. For this reason, professional development cannot be reduced to externally imposed training or compliance exercises. Instead, it must be rooted in the lived experiences and professional agency of teachers themselves. Teacher-led professional development is therefore most effective when it is directed by practitioners themselves rather than imposed externally. As Biesta (2009, p. 5) argues, educational processes “can be controlled by teachers and ought to be controlled by them,” while Eisner (2002) reminds us that growth is achieved through sustained process rather than short-term measures. Kennedy’s (2005) spectrum of CPD models suggests that the most transformative outcomes occur when teachers are granted autonomy, whilst Hilton et al. (2015) state that collaboration between teachers and leaders is key to sustaining development initiatives beyond the lifespan of individual programs. Sustained participation is also more likely to emerge within communities of practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991), where small groups of educators engage in shared endeavors and draw on peer expertise to reimagine their practice.

Zuber-Skerritt (2021) highlights how opportunities for “collaborative inquiry” enable educators to create “critical action research systems” in which the responsibility for improvement lies with those at the heart of practice. Building on this, teacher centered approaches to CPD, including communities of practice and practitioner-led action research have, in recent years, continued to demonstrate the effectiveness of embedding professional development within practice. This “inside-out” model (Gregson & Spedding, 2020) positions practitioners’ direct experiences as central to sustainable educational change and helps generate context-sensitive solutions that inspection regimes cannot achieve. Practitioner research initiatives such as FE research meets and networks (Jones et al., 2024) amplify practitioner voices, create safe spaces for innovation, and challenge externally imposed norms. Together, these developments point to a growing shift from top-down approaches to teacher-led, collaborative, and research-focused professional development, underpinned by the recognition of teacher agency as essential for lasting change.

1.2. Issues Arising

Agency can be defined as the capacity of “actors” to “critically shape their responses to problematic situations” (Biesta & Tedder, 2006, p. 11). Toom et al. (2017) describe teacher agency as a constructed capacity developed through interaction, participation, and reflection, which enables teachers to support both their own and others’ learning meaningfully. Agency is not a fixed individual trait; it is “a messy entanglement of the cultural, material, and relational conditions” (Philpott & Oates, 2017, p. 257) that emerges through the interaction between an actor’s capacities and their ecological conditions, suggesting that agency is contingent upon the context and conditions that shape its enactment (Biesta & Tedder, 2006). A key issue with teacher CPD is often the lack of agency afforded to teachers in selecting and shaping their own professional development (Rushton & Bird, 2024). Engagement with CPD in Further Education (FE) colleges is often hindered when participation is mandatory and choice is limited. Effective CPD requires a clear purpose, relevance, collaboration, and cooperation, as well as strong applicability to teaching contexts, especially given the competing demands on educators’ time (Collin & Smith, 2021). Furthermore, the credibility of those who facilitate CPD is crucial; teachers are more likely to engage with training when they trust and respect the facilitator’s expertise and practical experience.

The top–down nature of most CPD delivery in FE colleges in England reflects a technical–rational approach, where educational change and improvement are viewed as predictable, standardized processes. This model prioritizes organizational imperatives and compliance with external inspection requirements over the complex, context-dependent realities of teaching practice (Ball, 2003, 2018; Coffield, 2017). Rooted in the assumption that a universal “best practice” can be identified and applied mechanically, this approach treats professional development as a linear process of transmitting fixed knowledge rather than as an adaptive, practice-informed engagement with theory. As a result, CPD structures often reduce professional learning to a data-driven, risk-averse exercise, which may misinterpret regulatory expectations and undermine meaningful improvements in teaching and learning.

Ultimately, educational improvement must prioritize both student and teacher experiences, as both play an equally important role in shaping the overall educational experience. This might be achieved through a shift away from top–down models of CPD towards a “grassroots” or “ground–up” approach that centers on the experiences, problems, and challenges encountered by teachers in their practice, and the insights they have gained in trying to resolve them. While accountability to organizational objectives is undoubtedly necessary in publicly funded education systems, this study indicates that it is equally important to foster a supportive, practice-oriented approach to models of professional development which aim to secure change and improvement in educational practice. Data from this study suggest that in trusting educators to take ownership of their own training needs, a balance between organizational goals and authentic improvements in educational practice can be achieved.

1.3. Purpose

The purpose of the study reported here was twofold. Firstly, the intention was to examine whether traditional approaches to CPD align with practitioners’ professional needs and organizational priorities. The second was to explore whether more innovative, democratic, grassroots, practitioner-driven models involving engagement with creativity, cultural change, and aesthetic experience might better serve the dual aim of teachers’ professional growth and the improvement in educational practice. In the current policy environment, FE colleges operate under intense financial constraints and external compliance demands. Drawing on Ball’s (2003, 2018) concept of “performativity”, this study situates CPD within a broader critique of clusters of managerialist pressures, which adversely influence teachers’ professional development in circumstances where their experiences of CPD are often reduced to a series of highly prescribed, data-driven activities aimed at satisfying the demands and requirements of external accountability (Coffield, 2017; Gregson & Spedding, 2018) rather than the professional learning and development needs of teachers and their learners. This compliance-oriented approach not only limits, inhibits, dilutes, and perhaps even discourages teacher autonomy but also diminishes opportunities for meaningful teacher professional learning and development. Consequently, CPD managers face the persistent challenge of reconciling institutional imperatives with the concerns and intrinsic motivations of educators.

In exploring alternative approaches, this study considers how a gamified model of CPD might offer a route to enhance practitioner agency through the provision of greater choice, autonomy, and engagement. Gamification, through elements such as challenges, rewards, progression, and collaborative tasks, provides incentives for engagement (Davies, 2019; Deterding, 2012; Salmon, 2013) and can, under the right conditions, support teachers in taking ownership of their professional learning journeys (P. Buckley & Doyle, 2016). The intentions of this study align with the perspectives of C. Buckley and Husband (2020), who emphasize the importance of addressing teachers’ preferences for professional development that provide practical examples applicable to their specific teaching practices. They highlight the need for opportunities to foster reflective practice, ensuring that CPD is not only relevant but also supports teachers in critically engaging with their own teaching practices. This focus on meeting the individual needs of practitioners and the specific nuance of their practice is a key consideration in developing alternative models of CPD, which posit professional learning through collaborative, context-specific, and intrinsically motivated actions, in opposition to the more rigid professional development structures seen in traditional CPD workshops and “expert-led” training. Such models, it is argued, can offer an alternative and flexible approach to CPD delivery, one that can be tailored and adapted by individual staff to suit the unique requirements of their disciplines and contexts. This research examines ways in which possibilities to satisfy organizational priorities, developed to conform to external pressures such as Ofsted’s Education Inspection Framework (EIF), can be reconciled with CPD opportunities which offer staff choice and agency.

This study is therefore guided by three primary research questions:

- To what extent is practitioner motivation influenced by the gamification of CPD?

- In what ways can CPD satisfy both the individual needs of practitioners and the strategic priorities of organizations?

- What do teachers’ narratives reveal about how agency is enacted in CPD contexts?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

This study adopted a practice-focused, mixed-method, multiphase design, involving practitioner research conducted over time, using both qualitative and quantitative methods in an iterative and developmental process. It centered on a specific intervention, applied on a medium scale across an FE college with 3 campuses, aimed at developing an alternative model for achieving educational change and improvement. The research also sought to connect with the experiences of other educators working in similar contexts.

The methodology of practice-focused research had previously undergone ethical review, with Gelling and Munn-Giddings (2011) identifying seven stages as the basis for evaluating the ethics of this type of research project. These stages are value, scientific validity, fair participant selection, a favorable risk–benefit ratio, independent review, informed consent, and respect for enrolled participants. In this action research study, all decisions were guided by these seven stages, ensuring collaboration, shared cooperation, and flexibility with participants.

Practitioner research such as this is commonly associated with a mixed-method approach, combining both qualitative and quantitative data, and focusing on the implementation of change and improvement in practice rather than solely on the interpretation of meaning. In light of these considerations, this study adopted a pragmatic approach that avoided relying solely on quantitative data, assumed “controllable” variables, and predictions. Instead, the focus was on the real-world experiences of practitioners, ensuring that the study remained ethically sound, credible, and trustworthy in both its conduct and findings.

2.2. Paradigmal Considerations

Guided by a constructivist ontological perspective and a pragmatic–interpretivist approach, this study used surveys and semi-structured interviews to explore practitioners lived experiences of educational practice. While prioritizing qualitative depth, it included quantitative data to provide contextual baselines for interpreting the thoughts and feelings of participants.

This study primarily followed an ethnographic research design, using methods that allowed for an understanding of social experiences from the participants’ perspectives (Marsh & Furlong, 2002). The methodology employed aimed to create an environment conducive to open, honest conversation, which a purely positivist approach would not have facilitated. In most quantitative research, data collection methods are regarded as the “instrument” of analysis. However, qualitative and mixed-method studies are better suited to elaborating on observed themes within their context, with the aim of building theory rather than merely describing phenomena (Hallinger, 2016). In this pragmatic–interpretivist study, the researcher served as the instrument, making judgements about categorizing, coding, and contextualizing qualitative data (Nowell et al., 2017) primarily collected through participants’ spoken or written words.

2.3. Sampling

The sampling for this research was stratified and purposeful, ensuring a credible and trustworthy representation of practitioners’ voices. Across the three phases of the study, a total of 199 practitioners participated, representing a range of subject areas and roles within Further Education (FE). Participants varied in their length of teaching experience, from early-career teachers with less than two years’ experience to highly experienced practitioners with over 20 years in the sector, and in the levels of provision taught, including entry-level, vocational, and higher-level courses. These criteria were deliberately chosen to capture a broad range of perspectives and reflect the diverse needs of practitioners (DeYoreo, 2018). Further details on the participant numbers and sample composition across the distinct phases are provided in the data collection outline below.

While this study acknowledged the naturalistic convenience inherent in the researcher’s position as an insider researcher, a purposeful sampling approach was adopted to minimize sampling error and underrepresentation. Selection criteria included willingness to participate, availability during the research period, and alignment with the identified strata of teaching experience and level of provision. The demographic characteristics of the sample, covering all three phases, were transparently described during data analysis and discussion (Waterfield, 2018). Insider awareness enabled a more nuanced and trustworthy account of practitioners’ lived experiences.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the University of Sunderland’s Ethics Committee before data collection began, with all research conducted in accordance with the BERA Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research (BERA, 2024). Informed consent was sought from all participants, with a clear explanation of the study’s purpose and data usage provided through electronic submission. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any stage without consequence. No incentives were offered, and efforts were made to prevent any harm arising from participation. Participant confidentiality and anonymity were strictly maintained, with identifiable information excluded from surveys. Data were securely stored in password-protected cloud storage in accordance with the Data Protection Act 2018 (UK Government, 2018).

Recognizing the human nature of research, an awareness of the power dynamics between the researcher and participants was acknowledged, particularly as internal roles and responsibilities shifted during the study. Ethical praxis (Palaiologou et al., 2016) encouraged reflexivity and an ethical approach throughout, ensuring that all participants were treated with dignity, their voices heard, and their privacy safeguarded.

2.5. Data Collection

Methodologically, this study adopted inductive logic, beginning with specific cases and gradually moving towards broader inferences. The use of mixed-method data collection allowed for both qualitative and quantitative analyses, incorporating surveys and interviews. No predetermined hypotheses or theories were applied. Instead, the aim was to observe, interpret, and understand participants’ lived experiences, systematically analyzing the data through thematic analysis (Nowell et al., 2017) to identify patterns, sub-themes, and themes before developing findings, offering recommendations, and drawing conclusions.

Given the longitudinal nature of this doctoral research, which spanned 5 years, data were collected in multiple phases. These phases occasionally led to significant “key events” or “pivot points,” influenced by both controllable and uncontrollable factors. Such turning points were shaped by participant feedback and enriched by insights gained from related research.

2.5.1. Phase 1

Phase 1 involved an initial survey, using Google Forms, to explore teacher CPD perceptions, with 39 respondents (a 67% response rate) indicating strong interest among practitioners (Coe et al., 2017). The survey combined Likert, multiple-choice, and open-ended questions to capture insights into how participants perceived the existing CPD provision within the college, and it provided an opportunity to reflect on what would constitute “meaningful” professional development for themselves. On completion of the survey, participants were given the option of joining focus groups or arranging semi-structured interviews, ensuring deeper exploration of key themes (Scott & Usher, 1996). Interviews evolved conversationally to uncover underlying meanings (Rubin & Rubin, 2005).

Participants were selected from teachers employed across three departments in the college: Business and Law, Sport and Public Services, and Adult Education. The sample was designed to reflect a range of teaching contexts, including A-Levels, vocational and technical education, and adult learning, across qualification levels 1 to 5. To ensure diversity in representation, the sample included teachers with varying levels of teaching experience, ranging from two years or less to over 15 years. Both full-time and part-time employees were included, providing perspectives from different working arrangements. The sample also aimed for gender representation, although no quotas were applied. Participants engaged with CPD to varying degrees, with reported CPD hours typically ranging from less than 10 h to over 30 h per year. Participation in this study was voluntary.

2.5.2. Phase 2

Phase 2 involved developing a gamified online CPD platform using Google Apps for Education and Google Sites. The same 58 teaching staff from Phase 1 were given access to three courses, where their progress was tracked as they earned digital badges and received automated certificates upon completion. Participation was voluntary throughout to assess levels of interest in engagement rather than compliance. The platform included a resource repository, interactive activities, videos, and a shared tracker/leaderboard to encourage engagement. The sample was the same as that in Phase 1, with all participants invited to take part again. However, the response rate in Phase 2 was much lower (18%), with only six unique participants completing one of the three courses, and one participant completing two courses.

2.5.3. Phase 3

Insights from the Phase 1 survey and the shortcomings of Phase 2, particularly the lack of engagement with the online CPD platform, led to the pausing of gamified courses in Phase 3. This phase was further shaped by a change in the researcher’s leadership role within the FE college, which allowed greater influence over the internal CPD policy, and introduced new initiatives that prioritized teacher creativity, agency, and collaboration. These initiatives aimed to address teacher feedback from earlier phases, emphasizing choice over what previously, despite the best of intentions, was still perceived as a technical, rational, “one-size-fits-all” CPD approach. All 335 contracted teaching staff and 43 leaders/managers across 3 campuses were invited to provide feedback on these college-wide initiatives, which included the following:

- -

- [College] Projects—This initiative was college-wide and was launched during a whole-college staff development day in the first term. All teachers were encouraged to develop their own creative projects to enhance an aspect of teaching and learning within their teaching practice or another aspect of their role. These could be individual or group projects, conducted with or without the support of the Teaching, Learning, and Quality team, line management, or additional support teams. Teachers where encouraged to share their projects at a “showcase” event at the end of the school year, but no specific timeframes for completion of the projects was set.

- -

- Collaborative Teaching—This initiative was a peer collaboration initiative facilitating professional dialogue. All teachers could apply for a coffee voucher and meet with a colleague to discuss an element of their teaching, with the option to arrange peer observations, co-planning sessions, or follow-up meetings according to their preferences and schedules.

- -

- Theme of the Week—This initiative involved a weekly tip, trick, or training opportunity shared via EduArcade (see below) and email. It focused on a rotation of four key themes, highlighted in the college’s improvement plan: Innovative Pedagogy, EdTech, Preparing for Assessment, and Lost and Missed Learning (the latter linked to the COVID-19 recovery plan for colleges).

- -

- EduArcade—This initiative was an interactive website created for all teaching and support staff, offering advice, guidance, instructional videos, and training. It also promoted the other 3 initiatives, [College] Projects, Collaborative Teaching, and Theme of the Week, while providing a platform for staff to share examples ofgood practice from lesson observations and request additional training.

2.6. Data Analysis

Adopting a pragmatic mixed-method approach, this study sought to provide a trustworthy account of the lived experiences of practitioners within a specific context rather than pursue replication or generalizability. Descriptive statistics are presented as percentages to offer contextual understanding, particularly regarding the proportionality of responses. Qualitative data, drawn from open-ended survey questions and semi-structured interviews, are presented verbatim and anonymized to protect participants’ identities. All data were collected with prior participant consent; in cases where secondary sources were used, only publicly available trend or headline data were included.

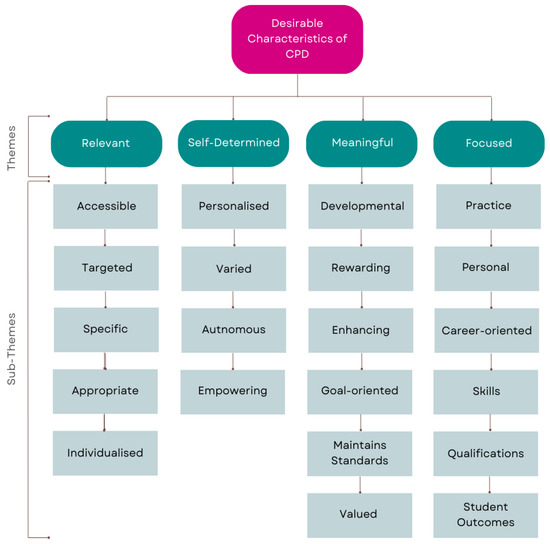

Thematic analysis followed the six-stage process outlined by Nowell et al. (2017), involving iterative coding to simplify and categorize data meaningfully (Denscombe, 2014). This process involved interpreting participants’ words not only at face value but also considering their deeper meanings and the context in which they were expressed to construct an authentic and trustworthy account of their lived experiences. Four major themes emerged through this process, as illustrated in Figure 1, showing the development from initial codes to broader thematic groupings. These qualitative themes were then triangulated with quantitative data, including responses to closed survey questions, engagement metrics, and other contextual measures.

Figure 1.

Desirable characteristics of CPD according to practitioners (including sub-themes).

Given the constructivist orientation of this study, the focus was on transparency in analysis and interpretation rather than external verification. Member checking, both formal and informal, was used to ensure that participants recognized their own experiences in the findings and to maintain the credibility and authenticity of the interpretations (Carl & Ravitch, 2018).

3. Results

3.1. Desirable Characteristics for CPD

The perspectives of teachers have been crucial in ensuring the credibility and authenticity of this research. Findings from Phase 1 identify four highly desirable characteristics of CPD according to participants in the pre-intervention survey: relevant, focused, meaningful, and self-determined (Figure 1). These themes were constructed through thematic analysis of qualitative data from open survey questions and practitioner interviews. The theme of “relevance” emerged from participants’ preferences for CPD that is available at convenient times and formats, targeted to specific areas of practice, directly related to their job roles, appropriate to their existing skills, and individualized to meet their needs. This highlights the importance of aligning professional development activities closely with the individual needs of practitioners when planning and delivering CPD. Similarly, participants expressed a desire for CPD to be “self-determined”, valuing opportunities to personalize their learning, choose from varied options, exercise autonomy over how and when they engage, and feel empowered to apply new skills. This emphasis on self-determination aligns with supporting teacher agency in professional development.

According to respondents, CPD should be “meaningful”, as participants favored professional development that is developmental, rewarding, enhancing, valuable, and goal oriented. Respondents noted that meaningful CPD builds upon existing skills, fosters a sense of achievement, makes tangible improvements to knowledge or competence, supports standards, and is focused on achieving specific goals. While meaningfulness often relates to the impact on student outcomes, participant feedback also ties it to a practice-focused approach. Finally, participants indicated that CPD should be “focused”, addressing individual needs by supporting skill development, teaching practice, career progression, and student outcomes. Some participants expressed a preference for formal qualifications through accredited training, while others prioritized developing personal skills and knowledge. This underscores a clear desire for CPD to have a direct, practical impact on teaching and learning, tailored to both professional and career goals.

Participants’ feedback reveals that current CPD models in FE often fail to engage practitioners meaningfully, primarily due to a disconnect between organizational priorities and individual professional goals. One participant stated, “The CPD given by the college I would love to be incredibly valuable, but I believe the themes chosen are not always that valuable to the teaching staff themselves”.

The themes outlined in Figure 1 provide a vital baseline for evaluating whether subsequent changes to CPD models, in Phases 2 and 3, meet the practical needs of practitioners in developing skills and knowledge, while also addressing their broader professional goals and expectations. In aligning CPD with teachers’ preferences and fostering a culture of creativity, choice, and professional agency, data from this study suggest that CPD can move beyond compliance-driven models to become a more meaningful and valued part of professional learning for teachers in FE contexts. This study therefore contributes to a deeper understanding of how CPD can be effectively designed and delivered to meet practitioners’ diverse needs.

3.2. One Size Fits No One

Phase 1 data also revealed a diversity of CPD models and content being offered, with participants generally positive about training opportunities. However, while CPD was perceived as valuable when focused, relevant, and self-directed, it was deemed less desirable when seen as lacking meaning or being overly prescribed and controlled. Despite organizational aims to improve teaching quality and efficiency, feedback indicated that CPD often failed to meet teachers’ individual needs, with one participant stating, “The activities that are relevant to teaching and learning often take a back seat to organizational agendas…and when choice is given it is sometimes not relevant to myself and my own needs and development”. Concerns around “box-ticking” practices surfaced frequently, with “...the shift from teaching and learning based CPD to more of a numbers and box ticking exercise evident over the years”, reflecting a widespread frustration with prescriptive models of professional development.

Findings highlight a critical tension between top–down CPD approaches driven by external pressures and teachers’ needs for agency-driven, context-sensitive professional learning. Without a shift towards practice-focused models that empower teachers, CPD risks remaining a compliance-driven exercise rather than a meaningful opportunity for professional growth. However, overcoming ingrained institutional norms requires bold leadership and a commitment to educational change.

Initial hopes that gamified learning might increase engagement proved to be misplaced. In the post-pandemic era, there appeared to be a clear preference among teachers for face-to-face learning, with limited enthusiasm for online methods, with interventions, such as [College] Projects and Collaborative Teaching, offering conditions for collaboration and agency, better received than the content being hosted online through the EduArcade and Theme of the Week.

These findings support the argument that one-size-fits-all approaches to CPD fail to consider the diverse and unique contexts in which educators work. The varied needs of individual teachers and the complexities of classroom environments make it unlikely that standardized, “off-the-shelf” solutions will deliver the promised impact. Instead, the voices of practitioners within this study indicate that education leaders and teachers should move away from the dominant technical–rational, top–down model of CPD, commonly seen in FE, and adopt a more pragmatic, democratic, and carefully tailored approach if they want to provide meaningful CPD to their staff. This requires rejecting the notion that a single CPD “event” can result in significant, sustainable improvement. Recognizing that there is no “silver bullet” and that genuine educational improvement depends on shared responsibility and accountability, problem finding, problem solving, and critique in context, may help educators and educational leaders to admit, and accept, that one size fits no one.

3.3. College Priorities and Teachers’ Priorities Tend to Differ

Qualitative responses to surveys and additional interviews/focus groups, gathered across all phases of data collection, infer that college priorities and individual teacher priorities often diverge, reflecting systemic challenges within the current model of educational change. One participant stated, “I’d probably say, maybe if I’m lucky, one day a year of staff development might be relevant to what I do”. The existing educational framework, particularly under the Ofsted EIF, tends to prioritize market-driven imperatives over core educational values. As a result, CPD is frequently shaped by what colleges choose to offer teachers rather than by what teachers need, with an emphasis on summative assessments and measurable outcomes.

This disparity appears to reflect wider responses to government policies, with colleges often focusing on short-term, event-based CPD rather than long-term, sustainable development programs. While this study did not gather specific data from CPD managers, the existing literature (Ball, 2018; Coffield, 2017; Gregson & Spedding, 2018) and the researcher’s own account and observations in the role of a CPD manager suggest that they can be placed in a challenging position, tasked with addressing complex, ongoing educational issues under significant pressure. These insights further highlight how tensions between institutional priorities and classroom realities create environments where pedagogical concerns are frequently overshadowed by performative demands.

While colleges must remain financially viable in an increasingly competitive educational landscape, it is crucial that their priorities align with those of the teaching staff to ensure that the true nature of classroom experiences is acknowledged. Without this alignment, the voices of teachers are overshadowed by external imperatives, which most participant voices suggested was typical within the models of CPD being employed prior to intervention. Instead, change must come from those engaged in the practice itself, and this is evident from the data in Phase 3 of this research, which demonstrates that alternative models of educational change, such as [College] Projects and Collaborative Teaching, can help bridge this gap. These types of interventions allow for a more authentic understanding of teaching needs, encouraging meaningful professional development that aligns both with individual teacher priorities and organizational goals.

Addressing research question two, findings from this study suggest that, although models such as [College] Projects and Collaborative Teaching offer a more holistic approach to professional learning, challenges persist in aligning these initiatives with broader institutional priorities and internal policies. Practices like graded lesson observations, for example, often undermine the open, honest, and trust-based culture that collaborative approaches aim to foster, particularly when such practices are associated with punitive performance measures. This tension between different approaches to educational improvement makes it difficult to balance the individual needs of practitioners with the strategic priorities of organizations.

3.4. The “Red Herring” of Gamification

A notable theme emerging from the data relates to the influence of gamification on practitioner motivation to engage with CPD, the focus of research question one. The overall impact of gamification on teacher motivation within this study remains inconclusive. While some teachers valued aspects of the gamified approach, describing it as “... great you can do it as and when and also tailor it to your own needs”, appreciating the “... choose your own adventure style”, and noting that “We can choose what applies to our classrooms”, the limited engagement with online training during Phase 2 might suggest otherwise. These findings therefore caution against superficial applications of gamification, underscoring the need for thoughtful integration that supports, rather than undermines, professional autonomy.

It appears that the key factor affecting motivation was not the mode of CPD delivery, in this case gamification, but rather the broader culture of CPD and how it was perceived by teachers. The findings of this study also suggest that motivation was more likely to be influenced by context and attitudes towards CPD rather than by specific tools or delivery methods, which fail to deliver a discernible or sustainable impact and most likely did not meet the desirable characteristics of CPD (Figure 1).

Consequently, I am unable to definitively state whether gamified CPD enhances teacher motivation. However, this initial attempt at intervention provided a valuable starting point for future changes and a shift away from taking a tool-centric approach to solving the problem. This change of perspective represented a significant turning point in this study, leading to a deeper exploration of the underlying models of educational change and improvement. It also drew attention to persistent issues with the technical–rational approach to managing educational quality, highlighting the need for alternative frameworks that better support teacher engagement and development.

3.5. Creating Conditions for Agency

In response to the limitations of the Phase 2 gamification approach and shaped by insights from Phase 1, new initiatives ([College] Projects, Collaborative Teaching, EduArcade, and Theme of the Week) were introduced in Phase 3 to better meet these teachers individual needs and promote agency and collaboration.

Teacher engagement with [College] Projects was overwhelmingly positive, with 160 submissions within a single academic year, highlighting teachers’ appreciation for autonomy and the opportunity to work on meaningful pedagogical development. Project outputs were wide-ranging. They included: teachers revising schemes of work and creating student-centered teaching resources; students producing and sharing homemade revision videos with each other; the engineering team, working with their students to refurbish a minibus that was later donated to a local charity; and a school sports partnership that not only earned the partner school a “Gold School Games Mark” but also led to the establishment of a long-term collaboration between the two institutions.

Feedback from participants provided insight into how agency was enacted through these alternative models of CPD, the focus of research question three, with comments such as “[I was] able to take ownership and focus on the aspects which were important to my teaching”, and “[I] enjoyed the fact that this was very much centered around our own areas of improvement, rather than being told what to improve on”. Others clearly valued the project-based approach, stating, “It’s a great idea, meaningful pedagogical development over a reasonable amount of time to actually have a measurable impact”, as well as “I like the idea of personal CPD and the use of our own initiative to drive a project from an idea to completion”.

It was also evident that the collaborative approach to CPD helped to erode some of the concerns around CPD being additional work, with one participant stating, “I was skeptical about this being more work for the team, however we were all really excited about our ideas and it allowed us the opportunity to come together as a team and share a vision that will hopefully benefit all of our courses”. Overall, clear value was placed upon this model of CPD by teachers, who, under conditions which support agency, were trusted to address their own training needs.

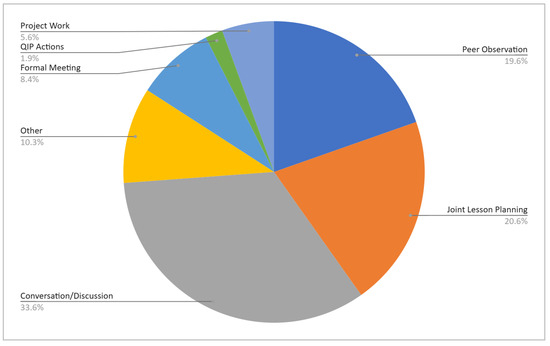

This initiative is closely aligned with Phase 1’s emphasis on CPD that allows teachers to focus on their personal development areas. Collaborative Teaching also saw significant engagement, with 136 peer meetings recorded, supporting the desire for collaborative and practice-focused professional development. Common activities included joint lesson planning, informal peer observation, project work, and more formal interactions (Figure 2). Even informal conversations over coffee led to useful insights, with staff reporting, anecdotally, that the opportunity to discuss practice openly in this forum was often more beneficial than in the previous, more formalized peer observations.

Figure 2.

The focus of Collaborative Teaching interactions.

In contrast, EduArcade and Theme of the Week received mixed responses. While some staff used the resources, others found them irrelevant or lacking focus, reinforcing Phase 1’s finding that CPD content must be meaningful to ensure engagement. Overall, the success of the [College] Projects and Collaborative Teaching initiatives supports the significance of teacher agency, collaboration, and focused, relevant professional development.

In addition, data from this study suggest that restricting teaching to rigid principles can inhibit creativity and hinder professional growth. Professional development should instead prioritize building self-aware, reflective practitioners by offering opportunities to experiment, critique, and refine new methods alongside established ones. Classroom practice, unlike static lesson plans, evolves through interaction with students and situational factors. Despite this, traditional CPD models often promote formulaic approaches, suggesting that assumed universal “excellent” or “best” practices can be simply and unproblematically applied across all contexts. Such models oversimplify complex educational challenges, offering superficial solutions in the form of “Top Tips” or standardized techniques, which often result in ineffective, ritualistic teaching routines.

The pressure to achieve putative “perfection”, coupled with increased administrative demands, can lead to teacher burnout. However, [College] Projects, and Collaborative Teaching offered more authentic, context-sensitive methods for teacher development, helping practitioners build knowledge, skills, and the qualities of mind and character needed for long-term success in diverse classroom settings, under conditions which support teacher agency.

4. Discussion

4.1. Challenging Traditional Approaches to CPD

Findings from this research highlight several key characteristics of effective CPD, as identified by practitioners. Teachers consistently expressed that “one size fits no one” when it comes to professional learning, suggesting that CPD models that adopt a uniform approach, often in a “symbiotic response” to external demands (Orr, 2020), fail to reflect the diverse needs, contexts, and experiences of individual teachers. This misalignment becomes particularly evident in the second key finding, which concerns the mismatch between college and teacher priorities. Teachers reported a clear disconnect between what the organization prioritizes in CPD and what they themselves find meaningful and valuable for their practice. Alignment between teacher priorities and broader institutional goals can help to create a more cohesive and supportive professional environment. However, the high levels of engagement with collaborative and teacher-centered CPD initiatives, such as [College] Projects and Collaborative Teaching, where teachers were provided with conditions that allowed agency to be enacted without a requirement to focus specifically on wider college priorities, suggest that alignment is not always necessary for both parties to be satisfied. While teachers pursued their own professional interests, the college also benefited through the development of individualized staff development goals, improvements in staff morale, and the emergence of pedagogical innovation. This mutual benefit demonstrates that supporting teacher agency can contribute to organizational development, even when CPD is not directly aligned with institutional targets.

A further finding, referred to as the “red herring” of gamification, reveals some skepticism from teachers regarding current CPD trends. Although game-based elements such as feedback loops and goal setting have been shown to enhance engagement, gamification of CPD, in this study, was viewed as a superficial solution. This finding reflects wider concerns that limiting teaching to surface-level strategies or rigid principles can inhibit creativity and hinder professional development (Thoilliez, 2019).

Another important finding focuses on creating conditions for agency. Teachers in this study emphasized the importance of autonomy, choice, and voice in their professional learning. CPD was seen as most effective when it supported practitioner agency and responded to the professional contexts in which teachers worked. These findings align with previous research highlighting the importance of a clear focus for CPD (Desimone, 2009; Opfer & Pedder, 2011), the value of meaningful and context-sensitive design (Collin & Smith, 2021), and the critical role of agency in professional learning (Biesta, 2015; Priestley et al., 2015).

Taken together, these findings suggest that sustainable and impactful CPD must move beyond compliance-driven models shaped by external accountability frameworks, such as Ofsted’s technical–rational, positivist approach to educational evaluation and improvement. Such top–down systems often exacerbate the disconnect between institutional goals and individual professional needs, fostering feelings of alienation among teachers (Shulman, 2000). Data from this research demonstrate that alternative, practitioner-led models of educational change, such as [College] Projects and Collaborative Teaching, help to bridge this gap. This supports the view that meaningful change must come from those engaged in the practice itself (Dunne, 2005).

The findings from this study suggest that CPD becomes more meaningful and relevant to teachers’ professional lives when it fosters creativity, choice, and agency. Aligning CPD design with practitioners’ needs and cultivating a culture of collaboration allows professional learning to move beyond compliance, becoming a valued and transformative part of teachers’ ongoing development. Building on these insights, the next section explores how promoting teacher agency alongside fostering aesthetic experience in professional learning can further enhance engagement and deepen the impact of CPD.

4.2. Promoting Teacher Agency and Aesthetic Experience in Professional Learning

Dewey’s notion of aesthetic experience (Dewey, 1934) stresses the significance of engaging with the world in ways that are meaningful, holistic, creative, and transformative, which directly challenges the conventional top–down models of CPD. For Dewey, an aesthetic experience is not a passive process but an active engagement in which individuals become fully immersed, responsive, and connected with their surroundings. In the context of CPD, this suggests the need to foster learning experiences where teachers feel both a sense of agency and connection, transforming professional development from a procedural task to a creative, meaningful endeavor. Teachers should be given the opportunity to engage with their practice creatively and in ways that resonate with their values and aspirations, akin to how an artist interacts with their medium. Teachers who embody creative agency not only sustain their own resilience but also model and foster these strengths in students, preparing them to navigate future challenges with agency (Anderson et al., 2022). The initiatives employed during this study which were deemed to be effective, [College] Projects and Collaborative Teaching, can be seen to support the notion of aesthetic experience that Dewey posits.

Similarly, Greene’s concept of wide-awakeness (Greene, 1988), which complements Dewey’s framework by emphasizing the importance of being alert to the possibilities and challenges in the world, can also be seen within the reported experiences of this study’s participants. For educators, wide-awakeness means stepping beyond the confines of routine and embracing new perspectives through engagement with their peers, students, and environments. When teachers are “wide awake”, they approach professional development with curiosity, empathy, and an openness to transformation. The launch of [College Projects] was a clear illustration of this. Through allowing teachers to identify areas for improvement based on personal reflection and student need, the initiative actively nurtures wide-awakeness, creating an environment in which educators can engage deeply with their practice and with one another.

Another concept discussed by Greene is that of imagination (Greene, 2005), which, she argues, plays a crucial role in the transformation of both teachers and students, enabling them to envision new possibilities and approaches to growth. In the context of CPD, imagination provides educators with the tools to challenge established norms and experiment with alternative practices that reflect their lived experiences. Initially, the exploration of gamification sought to envision a novel approach, but through reflection, it was realized that the deeper issue was not the approach itself but the restrictive structures within traditional CPD that limit teachers’ imaginative and creative potential. Evidently, the shift from rigid, prescriptive “transmission” models to teacher-led, collaborative, and exploratory projects, such as those seen in [College] Projects, supports the kind of imagination that can transform not only teachers’ professional practices but also the experiences of their students.

The reimagining of CPD through increased teacher agency, creativity, and collaboration aligns closely with Dewey’s and Greene’s ideas, offering a model of educational improvement that foregrounds aesthetic experience as well as wide-awakeness and imagination. These concepts advocate for a fundamental shift in how we approach teachers’ professional learning, moving from a duty-driven, prescribed activity to ongoing, dynamic, and creative engagement with one’s professional practice. Similarly, Mastrothanasis and Kladaki (2025) argue that an arts-based approach to professional learning can strengthen teachers’ professional identity by bridging theory and practice and providing an opportunity for reflection on how their teaching choices affect student learning and motivation. This shift is key to developing a transformative and meaningful approach to CPD that taps into the inherent potential of both educators and students, satisfying the “Desirable Characteristics of CPD” identified in Figure 1.

4.3. Implications for Future Practice and Research

This study highlights that in order to support educational improvement appropriately and effectively, teaching practices must be considered in their specific contexts, with meaningful change requiring alternatives to current CPD approaches. It critiques the traditional top–down approach to CPD, advocating for a more democratic, pragmatic model that emphasizes shared responsibility and accountability for educational improvement. While educators often experience frustration with the slow pace of change, this study demonstrates that change is possible. Education should be critical of the world it reflects, showing that shortcomings can be changed (Fielding, 2007). In line with the conceptualization of teacher agency (Priestley et al., 2015) and further supported by the findings of Philpott and Oates (2017), Rushton and Bird (2024), and Toom et al. (2021), this research highlights the critical role of agency in professional learning, emphasizing that educators are more likely to engage with CPD initiatives when they have a sense of ownership over their professional development. In response to the identified limitations of traditional CPD approaches, this research proposes “Collaborative Teaching” and “[College] Projects” as alternative models of CPD. This integrated approach promotes sustained professional learning through joint initiatives, enabling educators to co-construct knowledge and practices relevant to their specific contexts.

It is important to reiterate that this model is not presented as a recipe, blueprint, or universal solution but as a framework that requires adaptation and contextualization to fit diverse educational settings. Although similar models might exist within the FE sector, they do not appear to be broadly applied, and therefore an original contribution to how CPD might be facilitated has been made here. Furthermore, the findings of this study contribute to the current discourse on educational leadership by demonstrating that sustainable change in professional practice must be led from within, by those directly engaged in teaching and learning. Furthermore, this research aligns with Biesta’s (2009) critique of the adverse influences of an “age of measurement” in education, advocating for CPD that prioritizes pedagogical purpose over performative outcomes (Ball, 2003; Biesta, 2015). In foregrounding teacher agency and professional collaboration, the proposed model seeks to bridge the gap between organizational mandates and practitioner aspirations, ultimately promoting a culture of shared responsibility for educational improvement.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study highlights the critical role of teacher agency, relevance, and collaboration in shaping effective CPD while exposing the tensions between individual practitioner needs and organizational priorities. It recognizes that there is no “one-size-fits-all” approach to teacher education and CPD, particularly within frameworks shaped by external pressures such as Ofsted’s EIF. These accountability measures, while intended to uphold educational quality, often foster a culture of performativity, leading to feelings of apathy, fear, and powerlessness among teachers and education leaders. Instead of rigid, top–down approaches, this study advocates for models of CPD that empower teachers through agency, collaboration, and meaningful, context-sensitive learning.

Findings from this research demonstrate that initiatives such as [College] Projects and Collaborative Teaching provide a more effective and sustainable approach to professional development by fostering shared responsibility for improvement. When teachers are trusted to take ownership of their CPD, they engage more deeply, recognizing it as an opportunity for genuine professional growth rather than an imposed obligation. However, the misalignment between institutional priorities and classroom realities remains a significant challenge, as market-driven imperatives and external accountability structures continue to prioritize compliance over meaningful pedagogical development. In shifting towards a developmental, collaborative approach to accountability, education leaders can create a culture that values reflective and imaginative professional learning rather than formulaic, summative assessments.

This study supports the perspectives of Dewey (1934) and Greene (1988, 2005), reinforcing the idea that meaningful educational change arises from teacher agency and the cultivation of environments that encourage aesthetic experiences, critical awareness, and innovation. If more FE providers adopt these practitioner-led models of CPD, a sector-wide impact could be achieved. Moving away from outdated, top–down approaches would not only improve teaching quality and the student experience but might also help address critical sector challenges such as declining recruitment, rising teacher turnover, and retention issues. Ultimately, re-envisioning CPD in this way offers the potential for a more engaged, motivated, and empowered teaching workforce, leading to transformative and sustainable improvements in education.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the British Educational Research Association’s (BERA) Guidelines which operate in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, approved by the University of Sunderland Ethics Committee (Approval Code: 006706, Approval Date: 27 March 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported initially by the Education and Training Foundation (ETF) as part of an MPhil Practitioner Research Programme (PRP), and later through a PhD research scholarship as part of the Research Further initiative established collaboratively by the Association of Colleges and their partners to support, drive, and encourage further education-centered research that can help influence policy and practice.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the Data Availability Statement. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Anderson, R. C., Katz-Buonincontro, J., Livie, M., Land, J., Beard, N., & Bousselot, T. (2022). Reinvigorating the desire to teach: Teacher professional development for creativity, agency, stress reduction, and wellbeing. Frontiers in Education, 7, 848005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, S. J. (2003). The teacher’s soul and the terrors of performativity. Journal of Education Policy, 18(2), 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, S. J. (2018). The tragedy of state education in England: Reluctance, compromise, and muddle—A system in disarray. Journal of the British Academy, 6, 207–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G. (2009). Good education in an age of measurement: On the need to reconnect with the question of purpose in education. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21(1), 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G. (2015). Beautiful risk of education. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Biesta, G., & Tedder, M. (2006). How is agency possible? Towards an ecological understanding of agency-as-achievement [Unpublished manuscript]. The Learning Lives Project, University of Exeter. [Google Scholar]

- British Educational Research Association (BERA). (2024). Ethical guidelines for educational research (5th ed.). BERA. Available online: https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-fifth-edition-2024-online (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Buckley, C., & Husband, G. (2020). Lecturer identities and perceptions of CPD for supporting learning and teaching in FE and HE in the UK. International Journal of Management and Applied Research, 7(4), 432–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, P., & Doyle, E. (2016). Gamification and student motivation. Interactive Learning Environments, 24(6), 1162–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carl, N., & Ravitch, S. (2018). Member check. In B. B. Frey (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of educational research, measurement, and evaluation (Vol. 4, p. 1050). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Coe, R., Waring, M., Hedges, L., & Arthur, J. (2017). Research methods and methodologies in education (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Coffield, F. (2017). Will the leopard change its spots? A new model of inspection for Ofsted. UCL Institute of Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Collin, J., & Smith, E. (2021). Effective professional development: Guidance report. Education Endowment Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, J. (2019). Gamification for successful intranet adoption. Happeo. Available online: https://www.happeo.com/blog/gamification-drives-adoption-intranet (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Denscombe, M. (2014). The good research guide: For small-scale social research projects. McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Desimone, L. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S. (2012). Gamification: Designing for motivation. Interactions, 19(4), 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. (1934). Art as experience. Balch. [Google Scholar]

- DeYoreo, M. (2018). Stratified random sampling. In B. B. Frey (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of educational research, measurement, and evaluation (Vol. 4, p. 1624). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Dunne, J. (2005). An intricate fabric: Understanding the rationality of practice. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 13, 367–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisner, E. W. (2002). The arts and the creation of mind. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fielding, M. (2007). On the necessity of radical state education: Democracy and the common school. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 41(4), 539–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelling, L., & Munn-Giddings, C. (2011). Ethical review of action research: The challenges for researchers and research ethics committees. Research Ethics, 7(3), 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, M. (1988). The dialectic of freedom. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, M. (2005). Teaching in a moment of crisis: The spaces of imagination. New Educator, 1(2), 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregson, M., & Spedding, P. (2018, September 4–7). Learning together: Evaluating and improving further adult and vocational education through practice-focused research [Conference paper]. European Conference on Educational Research (ECER), Vocational Education and Training Network VETNET (pp. 165–172), Bolzano, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Gregson, M., & Spedding, P. (2020). Practice! Practice! Practice! In Practice-Focused Research in Further Adult and Vocational Education: Shifting Horizons of Educational Practice, Theory and Research (pp. 1–19). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hallinger, P. (2016). Bringing context out of the shadows of leadership. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 46(1), 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, A., Hilton, G., Dole, S., & Goos, M. (2015). School leaders as participants in teachers’ professional development: The impact on teachers’ and school leaders’ professional growth. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 40(12), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S., Scattergood, K., Rees, J., & Crowther, N. (2024). FEResearchmeet. A further education (FE) practitioner–researcher-led, initiative to share and develop capacity for research and scholarship across Wales and England: Analysing and theorising the period of initial development. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 29(3), 428–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A. (2005). Models of continuing professional development: A framework for analysis. Journal of in-service education, 31(2), 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, D., & Furlong, P. (2002). A skin not a sweater: Ontology and epistemology in political science. In Theory and methods in political science (2nd ed., pp. 17–41). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrothanasis, K., & Kladaki, M. (2025). Drama-based methodologies and teachers’ self-efficacy in reading instruction. Irish Educational Studies, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opfer, V. D., & Pedder, D. (2011). The lost promise of teacher professional development in England. European Journal of Teacher Education, 34(1), 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, K. (2020). Performativity and professional development: The gap between policy and practice in the English further education sector. In J. Tummons (Ed.), Professionalism in post-compulsory education and training (pp. 13–23). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Palaiologou, I., Needham, D., & Male, T. (2016). Doing research in education: Theory and practice. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Philpott, C., & Oates, C. (2017). Teacher agency and professional learning communities; what can Learning Rounds in Scotland teach us? Professional Development in Education, 43(3), 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestley, M., Biesta, G., & Robinson, S. (2015). Teacher agency: An ecological approach. Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, H., & Rubin, I. (2005). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Rushton, E. A., & Bird, A. (2024). Space as a lens for teacher agency: A case study of three beginning teachers in England, UK. The Curriculum Journal, 35(2), 254–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, G. (2013). E-tivities: The key to active online learning. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sarason, S. B. (1990). The predictable failure of educational reform: Can we change course before it’s too late? Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D., & Usher, R. (Eds.). (1996). Understanding educational research. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sennett, R. (2008). The craftsman. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman, L. S. (Ed.). (2000). Teaching as community property: Learning from change. In Teaching as Community Property: Essays on Higher Education (Vol. 106, pp. 24–26). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S. C. (2017). Contested knowledge: A critical review of the concept of differentiation in teaching and learning. Warwick Journal of Education—Transforming Teaching, 1, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Thoilliez, B. (2019). The craft, practice, and possibility of teaching. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 38(5), 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toom, A., Pietarinen, J., Soini, T., & Pyhältö, K. (2017). How does the learning environment in teacher education cultivate first year student teachers’ sense of professional agency in the professional community? Teaching and Teacher Education, 63, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toom, A., Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2021). Professional agency for learning as a key for developing teachers’ competencies? Education Sciences, 11(7), 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Government. (2018). Data protection act 2018, c.12. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2018/12/contents/enacted (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Waterfield, J. (2018). Convenience sampling. In B. B. Frey (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of educational research, measurement, and evaluation (Vol. 4, p. 403). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Zuber-Skerritt, O. (2021). Action research as a model of professional development. In Action research for change and development (pp. 112–135). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).