1. Introduction

Vocational education holds a particularly high status in Switzerland. Many young people choose this pathway in order to acquire appropriate qualifications for the labor market (

Kriesi et al., 2022). The Swiss vocational education system—comparable to those in Germany and Austria—exhibits certain unique features relative to other countries. The most prominent characteristic of vocational education in German-speaking countries is the so-called

dual system (

Ebner & Nikolai, 2010;

Trampusch, 2010), which also represents the most widespread form of vocational training in Switzerland (

Kriesi et al., 2022). The fundamental idea behind this model is that training takes place in two learning environments: the workplace and the vocational school (

Negrini, 2015).

Due to their close connection to the labor market and their cooperation with training companies, vocational schools must be able to respond quickly to social and economic trends—including digital transformation. Unlike general education schools, they are directly shaped by labor market dynamics and must continuously adapt to changing demands. For many young people, vocational schools therefore represent the last opportunity to acquire the digital skills necessary to manage an increasingly digital working world. This need is also supported by the strategic framework “Vocational Education and Training 2030,” which has been in implementation since 2018 and highlights the importance of digital transformation for successful vocational education (

Bosshard, 2018;

Ecoplan AG, 2017).

However, it is insufficient to reduce digital transformation in the school context solely to the integration of digital media into teaching and learning arrangements. Rather, a school improvement approach is required—one that considers the necessary structural and organizational conditions in order to conceptualize digital transformation holistically. The literature already offers several models that emphasize this holistic perspective (e.g.,

Eickelmann & Gerick, 2017;

Ilomäki & Lakkala, 2018).

Based on this premise, school management plays a particularly crucial role as a central actor within the school system. It is key to initiating and implementing innovations and change processes (

Bonsen, 2003;

Gräsel et al., 2020). This applies both to general school improvement processes (

Bonsen, 2016;

Cramer et al., 2021;

Pietsch & Tulowitzki, 2017;

Tulowitzki et al., 2019) and to developments related to digital transformation (

Breiter, 2019;

Dexter, 2018;

Gerick & Eickelmann, 2019;

Krein, 2023;

Tulowitzki et al., 2021). It is the responsibility of school management to foster an innovation-friendly working climate and a culture of collaboration in order to successfully manage (digitally related) development processes (

Brauckmann et al., 2019).

Previous research shows that the state of digital transformation in Swiss schools is generally rated positively. Moreover, the report “Digitalization in Education” indicates that there are regional differences within Switzerland: schools in the German-speaking part are better digitally equipped than those in the Latin-speaking regions (

Educa, 2021). However, these studies primarily focus on general education schools. Despite the recognized importance of digital transformation for vocational schools, they have rarely been the focus of research so far. Overall, there is a lack of representative studies on the digital development of upper-secondary schools in Switzerland (

Petko et al., 2022).

This article seeks to address this gap by investigating the current state of digital transformation in Swiss vocational schools and analyzing whether it is related with innovative school leadership practices as well as other individual school characteristics.

3. Research Questions

Following the previous considerations, it becomes evident that the majority of studies on digital transformation in the school context focus on general education schools. Although the current state of research indicates that the digital development state of Swiss schools can generally be assessed positively (e.g.,

Educa, 2021), it remains unclear to what extent this also applies to vocational schools. Given their close connection to the world of work, vocational schools represent a particularly relevant object of investigation (e.g.,

Gonon & Hägi, 2019;

Kriesi et al., 2022). Against this background, the following two research questions arise:

How can the digital development status of vocational schools in Switzerland be characterized from a school improvement perspective?

Can different profiles be identified based on the school management members’ perceptions of the digital development status of their schools?

Building on the theoretical and empirical background presented in

Section 2, it is clear that both structural and school-specific factors play a crucial role in the digital transformation of (vocational) schools. Since Switzerland is a federalist country, the structural issue of linguistic region and cantonal affiliation is closely linked to the question of financial resources, as the cantons are responsible for providing these resources. Structural conditions thus shape the opportunities and challenges schools face, while leadership behavior influences how schools strategically respond to these conditions and drive digital development internally.

Existing research suggests regional disparities in favor of the German-speaking part of Switzerland. Since the organization and funding of vocational education involve not only the cantons but also the federal government and private companies (

Educa, 2021;

SERI, 2022,

2023), the question arises as to whether similar effects can be observed in vocational schools. This leads to the third research question:

- 3.

To what extent are linguistic region and financial resources related to the school management members’ perception of the digital development status of vocational schools in Switzerland?

Although the literature frequently highlights the central role of school management in initiating and shaping (digitally) school improvement processes, empirical findings in this area remain limited. This gap motivates the fourth research question:

To what extent is (innovative) school leadership behavior related to the school management members’ perception of the digital development status of vocational schools in Switzerland?

- 4.

The overarching aim of this study is to contribute to the existing state of research by addressing these questions, thereby expanding the empirical evidence on the digital transformation of vocational schools in Switzerland and highlighting the role of school leadership in this context.

4. Methods

4.1. Study Design and Sample

To address the research questions, data were drawn from a quantitative online survey of school management members at vocational schools in Switzerland. The survey was conducted between February and March 2023. Given the heterogeneity in school size and organizational structure, it was up to each individual school principal to decide which individuals from the (extended) school management team would participate in the survey. The questionnaire was available in both German and French.

In total, n = 320 school management members from 135 vocational schools in Switzerland took part in the survey. More than two-thirds of the respondents (67.8%) came from the German-speaking part of Switzerland, while 32.2% worked at schools located in the so-called Latin part of the country, i.e., in the French- or Italian-speaking regions.

Regarding the roles of the respondents, the majority were either (deputy) school principals (44.4%) or heads of departments (46.7%). In addition, teachers (16.4%), IT coordinators (3.6%), and individuals with other school-related responsibilities (7.7%) also participated in the study. It is important to note that multiple selections were possible when indicating these roles.

4.2. Instrument

The questionnaire was designed to assess digital transformation as comprehensively as possible from a school improvement perspective, with particular emphasis on the actions of school leadership. The theoretical foundation for this was the model developed by

Petko et al. (

2018), as introduced in

Section 2.1. Accordingly, all eight conceptual dimensions of the model—two pertaining to

teacher readiness and six to

school readiness—were measured in alignment with the original framework. The focus, however, was not on the causal relationships between these two domains and the integration of digital media into teaching. Rather, the dimensions served as a reference framework for a broad assessment of the state of digital development from the perspective of school improvement.

For seven of the eight dimensions, the original scales developed by

Petko et al. (

2018) were employed. Only the dimension assessing teachers’ digital competencies was measured using an alternative scale (

Quast et al., 2021), as it was considered more suitable in terms of content. The scales used, along with their means, standard deviations, and reliability coefficients, are summarized in

Table 1. A detailed description of the items of the individual scales can be found in the appendix (

Appendix A).

In addition to the variables related to digital transformation, innovative school leadership practices were measured using three scales (

Diel & Steffens, 2010). It is important to note these scales capture general leadership behavior and are not explicitly tied to digitalization. This decision was made deliberately to allow for an investigation of whether general leadership practices—such as how innovations are approached more broadly—also influence the level of digital development within schools. Measuring leadership behavior specifically in the context of digital transformation at this point would risk conflating independent and dependent variables. The corresponding scale scores, including means, standard deviations, and reliability coefficients, are presented in

Table 2; the items used are also listed in the appendix (

Appendix B).

In addition, the questionnaire included two single-item measures: one capturing the linguistic region of the school in which the respondent is employed and another assessing the perceived adequacy of financial resources. Financial resources were rated on a six-point scale ranging from 1 = ‘very poor’ to 6 = ‘very good’. On average, respondents rated their school’s financial resources at M = 4.20 (SD = 1.16).

4.3. Analyses

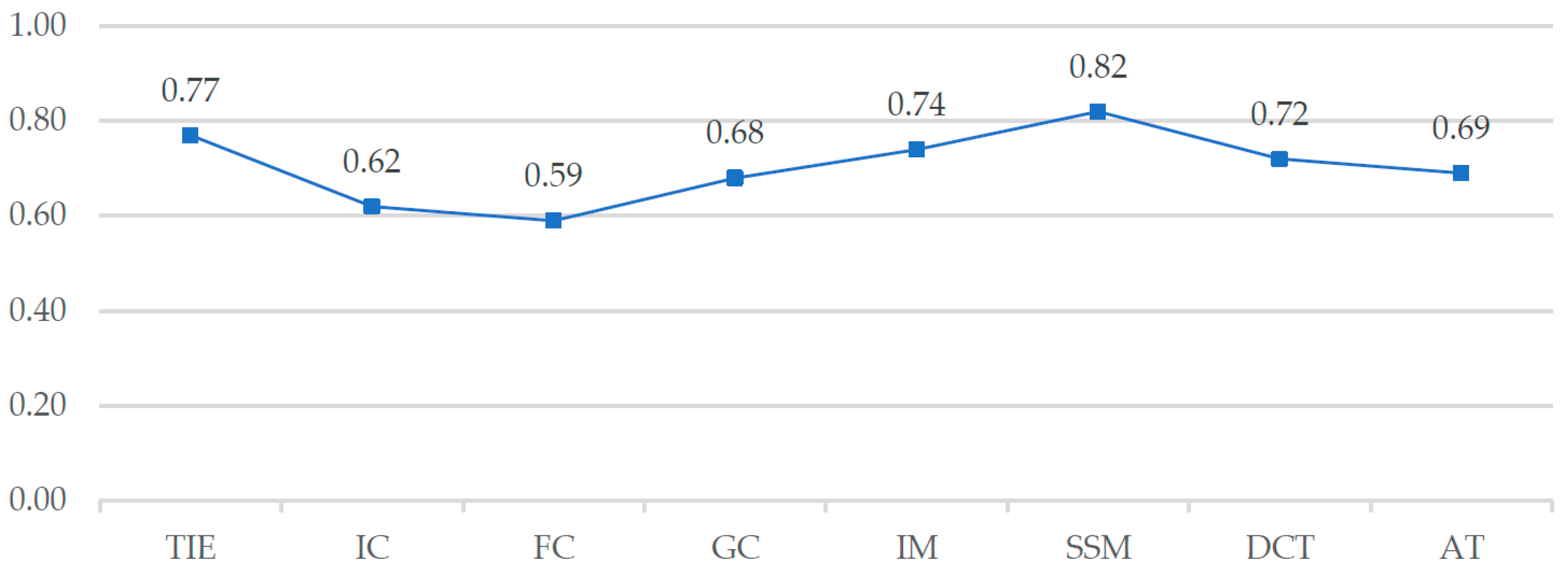

To analyze the digital development status of vocational schools in Switzerland, examining means and standard deviations is generally appropriate. However, as the scale for formal collaboration was based on a five-point Likert scale—unlike the six-point scales used for the other dimensions—a direct comparison across dimensions is limited. To enhance comparability, a min–max normalization was applied, whereby values were standardized by dividing them by the maximum number of scale points for each variable.

The subsequent methodological approach closely followed the procedure employed by

Eickelmann et al. (

2019), as described in

Section 2.2. First, a latent profile analysis (LPA) was conducted to determine whether distinct groups of school management members could be identified based on the perceived digital development status of their schools. Building on this classification, analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were performed to examine potential differences between the groups with regard to the perceived adequacy of financial resources and innovative school leadership practices.

To investigate a possible relation between the linguistic region and the digital development status, a chi-square test was conducted. All analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 29.0.0.0) and Mplus (version 8.7).

5. Results

The first research question of this paper focuses on how school management members perceive the level of digitalization-related development at vocational schools in Switzerland. The conceptual framework is based on the two dimensions of

teacher readiness and the six dimensions of

school readiness as defined by

Petko et al. (

2018), which are visualized in

Figure 2. On this scale, a value of 0.00 represents the lowest or least favorable expression, while a value of 1.00 indicates the highest or most favorable expression.

The analysis reveals that all dimensions exceed the theoretical mean value of M = 0.50, indicating consistently positive assessments. The dimensions support from school management (SSM) and technical infrastructure and equipment (TIE) receive particularly high ratings. In contrast, both formal and informal collaboration are rated comparatively lower.

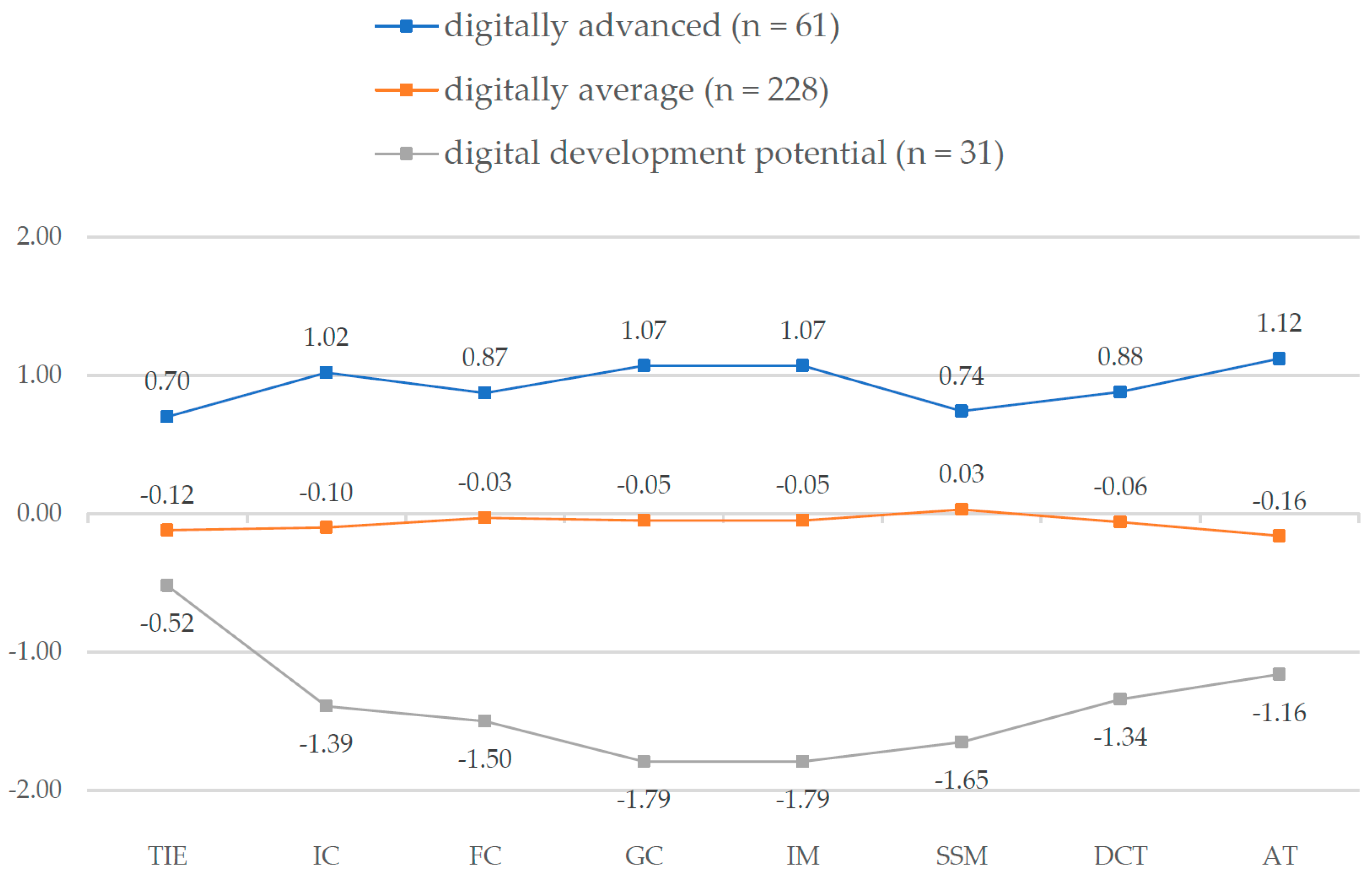

The second research question examined whether distinct groups could be identified among the surveyed school management members based on their perception of their school’s level of digitalization-related development. A latent profile analysis yielded a three-group solution (

Appendix C). Although solutions with a higher number of groups were statistically plausible, this approach was considered methodologically appropriate with regard to interpretability (

Marsh et al., 2004) and group sizes. According to

Masyn (

2013) and

Wang and Wang (

2012), the size of individual profiles should not fall below 5% of the total sample. The resulting three groups are illustrated in

Figure 3.

From the analysis, three distinguishable profiles of school management members emerge based on the perception of their schools’ digital development status: those perceiving their schools as digitally advanced, digitally average, and having digital development potential. The majority of respondents (n = 228) belongs to the middle group, followed by the digitally advanced group (n = 61) and those perceiving their schools as having digital development potential (n = 31). The smallest variance between the profiles is observed in the assessment of technical infrastructure and equipment (TIE), whereas the largest differences occur in the dimensions of goal clarity (GC) and importance (IM)—here, values for the most advanced and the least developed school groups differ by nearly three standard deviations.

Subsequently, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to examine whether the evaluation of financial resources differed among the three groups. The results indicate significant differences: those perceiving their schools as

digitally advanced rated their financial resources at M = 4.61 (SD = 1.18), the

digitally average group at M = 4.24 (SD = 1.09), and the group perceiving their schools as having

digital development potential at M = 3.21 (SD = 1.23). Follow-up post-hoc analyses (Bonferroni) revealed significant differences between the

digitally advanced group and the one with

development potential (

p < 0.001), as well as between the average and less developed groups (

p < 0.001). The effect size, with a partial η

2 of 0.92, can be classified as medium to large (

Ellis, 2010).

To investigate a potential association between the identified profiles and the linguistic region affiliation of the schools, a chi-square test was performed. The results demonstrate a significant relationship (

p < 0.001) with a medium effect size (Cramer’s V = 0.267;

Ellis, 2010).

The crosstab (

Table 3) reveals notable deviations between observed and expected cases, particularly for the profiles of

digitally advanced and

digital development potential. School management members from the German-speaking part of Switzerland are significantly more likely to be assigned to the most advanced profile and significantly less likely to the least developed profile, whereas the opposite pattern is observed in the Latin-speaking regions. Thus, a significant relation between the perceived digitalization-related development level of vocational schools and the linguistic region can be established—favoring the German-speaking region.

To address the fourth research question, which examines whether a relationship exists between innovative school leadership practices and the digitalization-related development level, further analyses of variance were conducted (

Table 4). The results indicate that all three scales measuring innovative leadership behavior are significantly higher in the more advanced profiles compared to the less developed groups. Post-hoc analyses (Tamhane) confirm significant differences in all pairwise comparisons. The effect sizes are consistently in a very high range. Therefore, a strong relation between the perceived level of digital development and innovative school leadership can be inferred.

6. Discussion

6.1. Summary and Interpretation of the Findings

The overarching objective of this paper was to analyze the digital development status of vocational schools in Switzerland and, based on this, to examine the extent to which it is related with specific school characteristics and innovative school leadership practices. To address this research aim, four research questions were formulated.

The first research question explored how the digital development status of vocational schools in Switzerland is generally perceived. The findings indicate that it is largely assessed positively by the participating school management members—a result that aligns with previous studies (

Educa, 2021). At the same time, the data reveal differences across the various dimensions of digital transformation. The

technical infrastructure and equipment (TIE) and the

support from school management (SSM) received particularly high ratings, whereas dimensions such as

formal collaboration (FC) were identified as having potential for further improvement.

The second research question, following the approach of

Eickelmann et al. (

2019), aimed to identify whether participants could be clustered into different groups based on their assessments of their school’s digital development status The analysis yielded three distinct profiles of respondents: those perceiving their schools as

digitally advanced,

digitally average, and having

digital development potential. The majority of the school management members (

n = 228) were assigned to the intermediate group. A closer look at the profiles shows that the extent of variation across the individual dimensions differs between the groups. While only small differences were found in relation to

technical infrastructure and equipment (TIE), greater variance was observed in

formal (FC) and

informal collaboration (IC). Although the study by

Eickelmann et al. (

2019) also identified distinct school profiles in terms of digitalization, a direct comparison is not possible, as the state of digital transformation was operationalized differently, and their analysis focused on schools themselves rather than on groups of school management members.

Building on this profiling, the study then examined whether there were relations between the perceived digital development status and (1) the linguistic region and (2) the perceptions of financial resources. In both cases, the results were consistent with expectations: schools located in the German-speaking part of Switzerland showed significantly higher levels of digital development—a pattern also found in general education settings (

Educa, 2021;

Oggenfuss & Wolter, 2021;

Suter et al., 2023). Furthermore, the findings regarding resource availability suggest that adequate funding appears to be a key prerequisite for successful digital transformation in schools.

The fourth and final research question investigated the relationship between innovative school leadership and the perceived digital development status. The findings demonstrate that innovative leadership practices are significantly more pronounced in the more digitally advanced profiles compared to the less developed groups. Effect sizes across all comparisons were large. These results reinforce the widely discussed importance of school leadership in the context of digital transformation processes (e.g.,

Dexter, 2018;

Gerick & Eickelmann, 2019;

Krein, 2023;

Tulowitzki et al., 2021;

Waffner, 2021). They highlight that innovative leadership practices—much like transformational leadership (see

Schmitz et al., 2023)—is related with positive school-level developments in terms of digital transformation.

In summary, the findings of this study are broadly consistent with existing research from the general education sector in Switzerland and suggest that these insights are transferable to vocational education and training (VET) settings. The observed effects related to the linguistic region and the financial resources also provide concrete starting points for education policy—for example, through regionally targeted funding initiatives or tailored support for schools with specific needs. Moreover, the results underscore the growing importance of strategic leadership roles in schools, particularly in terms of establishing conditions that foster innovation and school improvement in general. Against this background, it seems essential to align initial training and continuing professional development for (prospective) school leaders with the goal of building relevant leadership competencies and enabling their effective application in practice.

6.2. Limitations

Several limitations must be considered when interpreting the results, which are discussed below. First, the study relied exclusively on data collected from school management members. While this decision aligns well with the thematic focus of the study, it introduces a methodological limitation: the possibility of a common method bias cannot be ruled out (cf.

Söhnchen, 2007). This refers to the fact that both the independent and dependent variables were assessed by the same individuals, which may lead to biases in variable distributions and relations.

In addition, schools were allowed to decide for themselves which members of their extended leadership teams would participate in the survey. This led, on the one hand, to a varying number of respondents per school. This unequal representation across schools as well as the nested data structure—individuals within schools—should be taken into account when interpreting the results. Accordingly, no direct conclusions should be drawn at the school level based on individual perceptions. On the other hand, it is plausible that perceptions of the school’s digital development status differ depending on the roles and areas of responsibility of the respondents. As a result, members from the same school were in some cases assigned to different profiles in the latent profile analysis. However, this outcome may be substantively reasonable. It is conceivable that individuals within the same school might hold different views—for example, regarding goal clarity (GC) or informal collaboration (IC). Therefore, when interpreting the findings, it is important to keep in mind that the data reflect subjective perceptions of school management members. Objective indicators—such as the number of digital devices available—were not included in the analyses.

At the same time, the variation in perceptions of the digital development status within the same school, and the resulting assignment of school management members to different profiles, opens up important considerations for future research. Such differences may reflect underlying leadership dynamics within schools. They could indicate a lack of shared vision or inconsistent communication, but may also represent a diversity of legitimate perspectives that naturally arise from differentiated responsibilities and experiences within leadership teams. In this sense, the existence of multiple perspectives within a single school could potentially be viewed not as a weakness, but as a constructive resource for school development. Future studies could explore these dynamics more closely, examining the implications of perceptual diversity for leadership practice and organizational learning in schools.

Another potential source of bias lies in the fact that school management members were also asked to assess their own innovative leadership practices. In this context, socially desirable responses cannot be entirely ruled out. However, any systematic overestimation would likely affect the overall level of reported innovative leadership practices rather than the differences between the identified profiles.

Lastly, it should be noted that school leadership is a complex and multidimensional construct. In this study, it was operationalized using only three scales related to innovative leadership practices. Future research would benefit from a more differentiated approach that captures a broader range of leadership dimensions.

7. Conclusions

The results of this study indicate that the digital development status of Swiss vocational schools is generally positive. At the same time, the findings highlight the need for a more differentiated analysis—both in terms of the various dimensions of digital transformation and in regard to school-specific differences, such as linguistic region or leadership practices.

A key insight from this study is the significant role played by school leadership in initiating and shaping (digital) school improvement processes. The function and leadership behavior of school management prove to be crucial drivers of progress at the school level. From an educational policy perspective—and in line with a systemic view—this underscores the need for school management members to possess the necessary leadership competencies. This, in turn, implies a responsibility on the part of the education system to provide appropriate support structures and qualification opportunities—both in initial training and through ongoing professional development. Without such supportive conditions, it would be unreasonable to expect school management to guide schools effectively in increasingly dynamic environments.

For future research, it would be valuable to further investigate the causes of regional disparities between linguistic areas in Switzerland. While the higher importance of the dual system in the German-speaking region offers a preliminary explanation (cf.

Kriesi et al., 2022), additional contextual and sociocultural factors are likely to play a role as well (

Educa, 2021;

Suter et al., 2023). In this context, it would also be desirable for future studies to examine the relationships between linguistic regional affiliation and school leadership behavior. Understanding how regional contexts influence leadership practices could provide deeper insights into the mechanisms driving digital transformation in vocational schools.

Moreover, recent developments suggest that the importance of principals and school management members as agents of change will continue to grow. Further empirical studies are therefore needed to deepen the evidence base and provide policymakers with a solid foundation for targeted actions in this area. At the same time, future research should also focus on other school actors—particularly teachers—who also play an essential role in successful school improvement. A multiperspective research approach that incorporates the views of various actors within the school system would be especially beneficial here (

Petko et al., 2018;

Suter et al., 2023). It seems quite likely that different stakeholders—also in the context of digital transformation—may perceive the situation in schools differently (

Rauseo et al., 2022).