Bridging Theory and Practice with Immersive Virtual Reality: A Study on Transfer Facilitation in VET

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical and Empirical Background

2.1. Potential of IVR as an Educational Technology

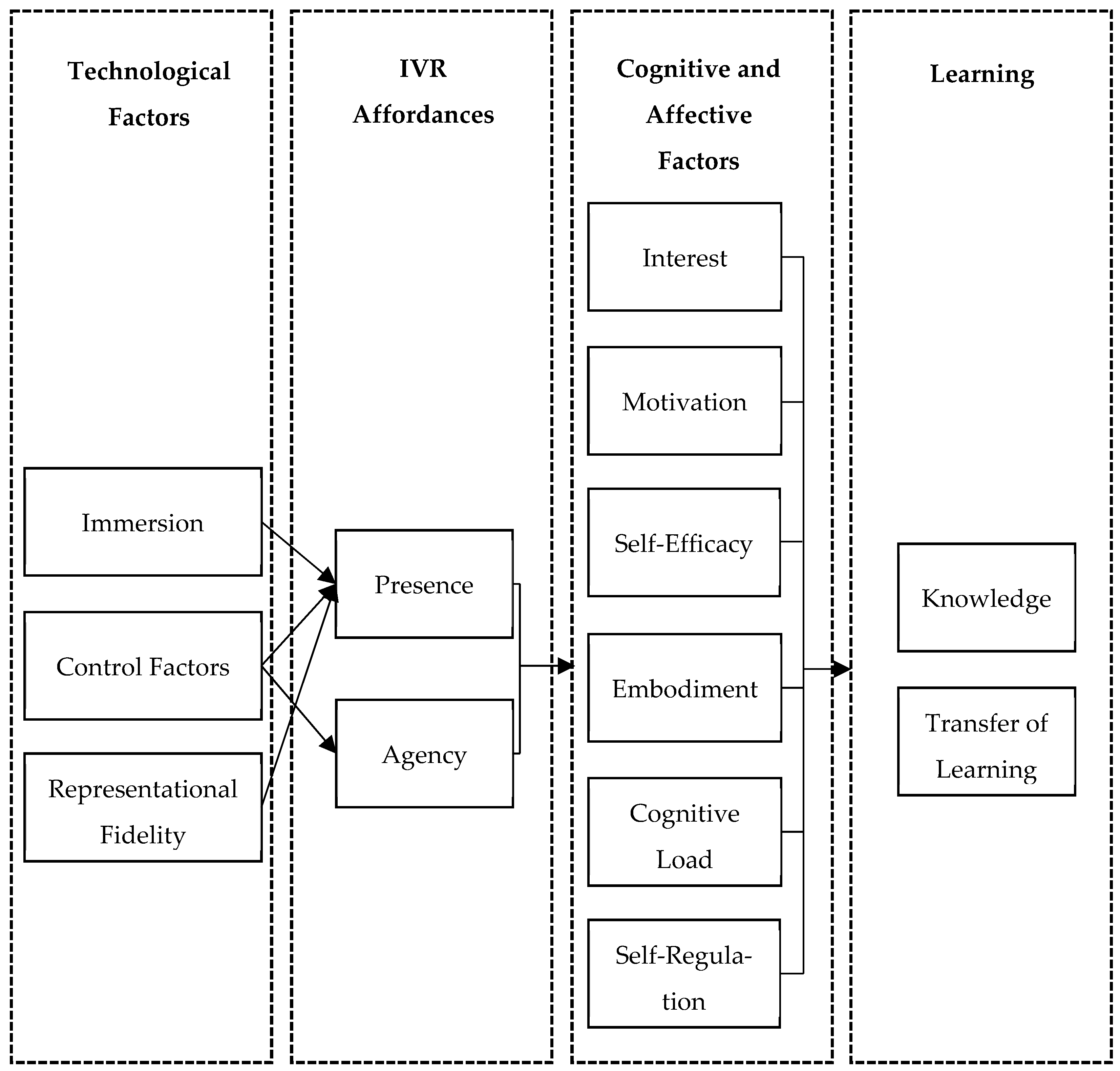

2.2. IVR-Based Learning

2.3. Knowledge Transfer

2.4. State of Research

3. Hypotheses

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Research Design and Sample

4.1.1. IVR Group

4.1.2. Non-IVR-Group

4.2. Instruments

- Relevant subject knowledge was assessed at two measurement times (before and after the intervention) using a specially developed test to examine the performance development between the two groups (IVR group and non-IVR group). The test included 26 items that covered content taught during the intervention. It was time-limited to 30 min and administered in a single-choice format. One point was awarded for each correct answer, resulting in a maximum score of 26 points. The content of the items focused on the four main topics: sales zones, product carriers, supermarket routing, and shelf placement. The reliability of the test was calculated using Item Response Theory (IRT) analysis, resulting in an EAP/PV reliability (expected a posteriori/plausible values) of 0.71. The EAP/PV reliability indicates how well the estimated person’s abilities reflect the individual’s actual abilities.

- Additionally, a questionnaire was distributed to the IVR group immediately after the fourth lesson to assess the factors described in CAMIL. The items for IVR affordances (presence and agency) as well as cognitive and affective factors were adapted from the work of Petersen et al. (2022). In addition, the assessment of self-regulation was based on the work of Tiaden (2006), while the extraneous cognitive load was assessed according to Klepsch et al. (2017). All items were measured using 5-point Likert scales.

- In order to obtain more insights regarding the transfer-enhancing potential of IVR, the measurement of transfer-related self-efficacy was used, as it can easily be indicated by the learners themselves. The assessment of transfer-related self-efficacy was conducted using four items based on the works of Kauffeld et al. (2009), Stäudel (1988), and Snyder et al. (1991). These items were also assessed using a 5-point Likert scale.

5. Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allcoat, D., & von Mühlenen, A. (2018). Learning in virtual reality: Effects on performance, emotion and engagement. Research in Learning Technology, 26, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossard, C., Kermarrec, G., Buche, C., & Tisseau, J. (2008). Transfer of learning in virtual environments: A new challenge? Virtual Reality, 12(3), 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchner, J., & Kerres, M. (2023). Media comparison studies dominate comparative research on augmented reality in education. Computers & Education, 195, 104711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehler, K., & Kohne, A. (2019). Lernen mit Virtual Reality: Chancen und Möglichkeiten der digitalen Aus-und Fortbildung [Learning with virtual reality: Opportunities and potentials of digital initial and continuing education]. In M. Groß, M. Müller-Wiegand, & D. F. Pinnow (Eds.), Zukunftsfähige Unternehmensführung: Ideen, Konzepte und Praxisbeispiele (pp. 209–224). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, E. W. L., & Ho, D. C. H. (2001). A review of transfer of training studies in the past decade. Personnel Review, 30(1), 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concannon, B. J., Esmail, S., & Roduta Roberts, M. (2019). Head-mounted display virtual reality in post-secondary education and skill training. Frontiers in Education, 4, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, M., Kablitz, D., & Schumann, S. (2024). Learning effectiveness of immersive virtual reality in education and training: A systematic review of findings. Computers & Education: X Reality, 4, 100053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gegenfurtner, A. (2011). Motivation and transfer in professional training: A meta-analysis of the moderating effects of knowledge type, instruction, and assessment conditions. Educational Research Review, 3(6), 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gegenfurtner, A., & Vauras, M. (2012). Age-related differences in the relation between motivation to learn and transfer of training in adult continuing education. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 37(1), 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granados Cannawurf, R. A. (2005). Trainings-transfer: Eine Langzeitstudie der zugrunde liegenden Prozesse [Training transfer: A long-term study of the underlying processes]. JLUpub. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, D., McKechnie, J., Edgerton, E., & Wilson, C. (2021). Immersive virtual reality as a pedagogical tool in education: A systematic literature review of quantitative learning outcomes and experimental design. Journal of Computers in Education, 8(1), 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellriegel, J., & Čubela, D. (2018). Das Potenzial von Virtual Reality für den schulischen Unterricht: Eine Konstruktivistische Sicht [The potential of virtual reality for classroom instruction: A constructivist perspective]. MedienPädagogik, Occasional Papers, 58–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hense, J., & Mandl, H. (2011). Transfer in der beruflichen Weiterbildung [Transfer in vocational continuing education]. In O. Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia (Ed.), Stationen empirischer Bildungsforschung: Traditionslinien und Perspektiven (pp. 249–263). VS Verlag. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M. C., Gutworth, M. B., & Jacobs, R. R. (2021). A meta-analysis of virtual reality training programs. Computers in Human Behavior, 121, 106808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. L., Blume, B. D., Ford, J. K., & Baldwin, T. T. (2015). A tale of two transfers: Disentangling maximum and typical transfer and their respective predictors. Journal of Business and Psychology, 30(4), 709–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kablitz, D., Conrad, M., & Schumann, S. (2023). Immersive VR-based instruction in vocational schools: Effects on domain-specific knowledge and wellbeing of retail trainees. Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training, 15(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffeld, S., Brennecke, J., & Strack, M. (2009). Erfolge sichtbar machen: Das Maßnahmen-Erfolgs-Inventar (MEI) zur Bewertung von Trainings [Making success visible: The measures success inventory (MEI) for the evaluation of training programs]. In S. Kauffeld, S. Grote, & E. Frieling (Eds.), Handbuch Kompetenzentwicklung (pp. 55–78). Schaffer-Poeschel. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K. G., Oertel, C., Dobricki, M., Olsen, J. K., Coppi, A. E., Cattaneo, A., & Dillenbourg, P. (2020). Using immersive virtual reality to support designing skills in vocational education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(6), 2199–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepsch, M., Schmitz, F., & Seufert, T. (2017). Development and validation of two instruments measuring intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive load. Frontiers in Psychology, 16(8), 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I. J. (2020). Applying virtual reality for learning woodworking in the vocational training of batch wood furniture production. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(3), 1448–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loke, S. K. (2015). How do virtual world experiences bring about learning? A critical review of theories. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 31(1), 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowell, V. L., & Tagare, D. (2023). Authentic learning and fidelity in virtual reality learning experiences for self-efficacy and transfer. Computers & Education: X Reality, 2, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makransky, G., & Petersen, G. B. (2021). The Cognitive Affective Model of Immersive Learning (CAMIL): A theoretical research-based model of learning in immersive virtual reality. Educational Psychology Review, 33(1), 937–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makransky, G., & Petersen, G. B. (2023). The theory of immersive collaborative learning (TICOL). Educational Psychology Review, 35(4), 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marougkas, A., Troussas, C., Krouska, A., & Sgouropoulou, C. (2023). Virtual reality in education: A review of learning theories, approaches and methodologies for the last decade. Electronics, 12(13), 2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J. W., & Fletcher, P. C. (2012). Sense of agency in health and disease: A review of cue integration approaches. Consciousness and Cognition, 21(1), 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulders, M., Buchner, J., & Kerres, M. (2022). Virtual reality in vocational training: A study demonstrating the potential of a VR-based vehicle painting simulator for skills acquisition in apprenticeship training. Technology Knowledge and Learning, 29(2), 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissim, Y., & Weissblueth, E. (2017). Virtual reality (VR) as a source for self-efficacy in teacher training. International Education Studies, 10(8), 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissim, Y., & Weissblueth, E. (2024). Virtual reality as a vehicle to transform teachers’ personal self-efficacy into professional self-efficacy. Cogent Education, 11(1), 2372155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, G. B., Petkakis, G., & Makransky, G. (2022). A study of how immersion and interactivity drive VR learning. Computers & Education, 179, 104429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radianti, J., Majchrzak, T. A., Fromm, J., & Wohlgenannt, I. (2020). A systematic review of immersive virtual reality applications for higher education: Design elements, lessons learned, and research agenda. Computers & Education, 147, 103778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, M., & Lakshmi Priya, G. G. (2020). Factors affecting the intention to use virtual reality in education. Psychology and Education, 57(9), 2014–2022. [Google Scholar]

- Schwan, S., & Buder, J. (2006). Virtuelle Realität und E-Learning [Virtual reality and E-learning]. Goethe-Universität Frankfurt. Available online: http://www.e-teaching.org/didaktik/gestaltung/vr/vr.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Snyder, C. R., Harris, C., Anderson, J. R., Holleran, S. A., Irving, L. M., Sigmon, S. T., Yoshinobu, L., Gibb, J., Langelle, C., & Harney, P. (1991). The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(4), 570–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stäudel, T. (1988). Der Kompetenzfragebogen—Überprüfung eines Verfahrens der Selbsteinschätzung der heuristischen Kompetenz, belastender Emotionen und Verhaltenstendenzen beim Lösen komplexer probleme [The competence questionnaire—Evaluation of a self-assessment method for heuristic competence, stressful emotions, and behavioral tendencies in solving complex problems]. Diagnostica, 34, 136–148. [Google Scholar]

- Thomann, H., Zimmermann, J., & Deutscher, V. (2024). How effective is immersive VR for vocational education? Analyzing knowledge gains and motivational effects. Computers & Education, 220, 105127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiaden, C. (2006). Selbstreguliertes Lernen in der Berufsbildung: Lernstrategien messen und fördern [Self-regulated learning in vocational education and training: Measuring and promoting learning strategies]. Available online: https://edudoc.ch/record/17453?ln=de (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- von Solga, M. (2011). Förderung von Lerntransfer [Promoting learning transfer]. In J. Ryschka, M. Solga, & A. Mattenklott (Eds.), Praxishandbuch Personalentwicklung: Instrumente, Konzepte, Beispiele (3rd ed., pp. 339–368). Gabler. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, K. (2013). Verknüpfung schulischen und betrieblichen Lernens und Lehrens–Erfahrungen, Einstellungen und Erwartungen der Akteure dualer Ausbildung [Linking school-based and workplace learning and teaching—Experiences, attitudes, and expectations of stakeholders in dual vocational education and training]. bwp@ Spezial, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wißhak, S. (2022). Transfer in der berufsbezogenen Weiterbildung: Systematisches Literaturreview und Synthese mit Blick auf die Handlungsmöglichkeiten der Lehrenden [Transfer in vocational continuing education: A systematic literature review and synthesis with a focus on teachers’ options for action]. Zeitschrift für Weiterbildungsforschung, 45(1), 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zender, R. (2020). Workshop HandLeVR 2020. In Proceedings of DELFI workshops 2020. Gesellschaft für Informatik eVz. [Google Scholar]

- Zinn, B. (2019). Lehren und Lernen zwischen Virtualität und Realität [Teaching and learning between virtuality and reality]. Journal of Technical Education, 7(1), 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| IVR Group (n = 77) | Non-IVR Group (n = 64) | Total (N = 141) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | n | 45 (58.4%) | 27 (42.2%) | 72 (51.1%) |

| Female | n | 28 (36.4%) | 27 (42.2%) | 55 (39.00%) |

| n.a. | n | 4 (5.2%) | 10 (15.6%) | 14 (9.9%) |

| Age | M (SD) | 19.58 (2.90) | 20.15 (2.26) | 19.82 (2.66) |

| Scales (No. of Items) | M (SD) | Reliability | Example Item |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain-specific knowledge | EAP/PV | ||

| Pretest (26) 1 | 8.66 (3.27) | 0.62 | Which of the following areas is typically found in a salesroom? |

| Posttest (26) 1 | 13.58 (4.72) | 0.76 | What is understood by the term “secondary placement”? |

| Further Variables * | α | ||

| Agency (4) | 4.04 (0.75) | 0.68 | During the lesson, my experiences and actions were under my control. |

| Physical Presence (5) | 3.51 (0.92) | 0.90 | The virtual environment seemed real to me. |

| Academic self-efficacy (4) | 4.13 (0.86) | 0.94 | I’m confident I can understand the basic concepts of salesroom design. |

| Situational interest (6) | 4.12 (0.84) | 0.93 | The lesson captured my attention. |

| Motivation (5) | 4.03 (0.84) | 0.92 | I enjoyed working on the topic of salesroom design. |

| Embodiment (3) | 3.31 (1.15) | 0.91 | Performing gestures/movements during the lesson helped me learn. |

| Extraneous cognitive load (3) | 2.21 (0.90) | 0.82 | During the lessons it was difficult to link the most important content together. |

| Self-regulation (3) | 3.71 (0.84) | 0.78 | While working on the task, I kept asking myself whether I could improve my approach. |

| Transfer-related self-efficacy (4) | 3.50 (0.81) | 0.79 | I have the confidence to apply what I have learned to my work. |

| IVR Group (n = 77) | Non-IVR Group (n = 64) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension | M (SD) | p | d | ||

| Transfer-related self-efficacy 1 | 3.66 (0.77) | 3.34 (0.82) | 0.036 | 0.39 | |

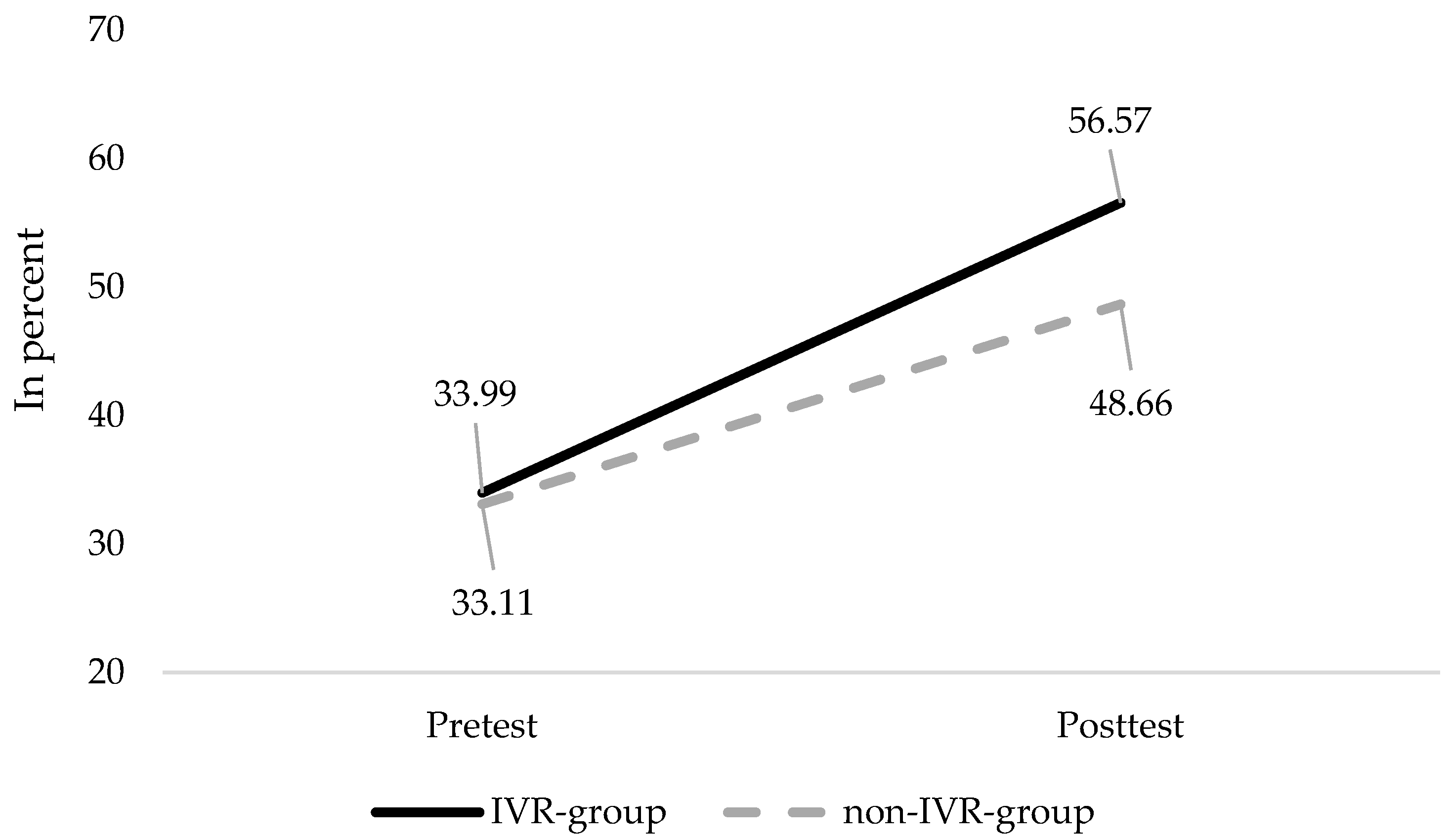

| Knowledge acquisition (posttest) 2 | 56.36 (13.51) | 48.31 (14.22) | 0.002 | 0.58 | |

| (DV: Posttest Score) | F | p | Partial Eta Squared |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time | 159.79 | <0.001 | 0.617 |

| Group (IVR/non-IVR) | 4.17 | 0.044 | 0.040 |

| Time × group | 5.44 | <0.022 | 0.052 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer-rel. self-eff. (1) | -- | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.37 * | 0.53 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.78 ** | 0.48 ** | −0.20 | 0.33 * |

| Posttest (2) | -- | 0.46 ** | 0.00 | 0.39 ** | 0.29 * | 0.20 | 0.04 | −0.09 | 0.28 * | |

| Agency (3) | -- | 0.22 | 0.29 * | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.12 | −0.35* | 0.04 | ||

| Presence (4) | -- | 0.59 ** | 0.61 ** | 0.27 * | 0.62 ** | 0.03 | 0.30 * | |||

| Interest (5) | -- | 0.89 ** | 0.60 ** | 0.49 ** | −0.11 | 0.45 ** | ||||

| Motivation (6) | -- | 0.51 ** | 0.50 ** | −0.08 | 0.35 ** | |||||

| Self-efficacy (7) | -- | 0.29 * | –0.24 * | 0.41 ** | ||||||

| Embodiment (8) | -- | −0.04 | 0.23 | |||||||

| Cognitive load (9) | -- | 0.14 | ||||||||

| Self-regulation (10) | -- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kablitz, D. Bridging Theory and Practice with Immersive Virtual Reality: A Study on Transfer Facilitation in VET. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 959. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15080959

Kablitz D. Bridging Theory and Practice with Immersive Virtual Reality: A Study on Transfer Facilitation in VET. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(8):959. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15080959

Chicago/Turabian StyleKablitz, David. 2025. "Bridging Theory and Practice with Immersive Virtual Reality: A Study on Transfer Facilitation in VET" Education Sciences 15, no. 8: 959. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15080959

APA StyleKablitz, D. (2025). Bridging Theory and Practice with Immersive Virtual Reality: A Study on Transfer Facilitation in VET. Education Sciences, 15(8), 959. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15080959