1. Introduction

Beginning a teaching career is widely acknowledged as a period of heightened stress, even under typical conditions. Early-career teachers (ECTs), generally defined as those within their first five years of service, often face considerable challenges related to workload, classroom management, and professional identity formation (

Johnson et al., 2012;

Mansfield et al., 2016). These challenges are exacerbated by limited experience, high expectations, and the need to quickly adapt to school culture and professional norms. Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, early attrition was a well-documented concern, with many ECTs exiting the profession within their first few years due to burnout, lack of support, or unmet expectations (

Ingersoll, 2012).

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 dramatically intensified these stressors. ECTs were abruptly required to deliver remote or hybrid instruction, often with limited training, resources, or support (

Kim et al., 2021;

Pressley et al., 2021). At the same time, many had experienced curtailed teacher preparation experiences, such as shortened practicums or reduced mentoring, resulting in lower self-efficacy as they transitioned into full-time teaching roles (

Allen et al., 2020). This convergence of disrupted training and difficult workplace entry conditions has been described as a “double transition” crisis for the 2020–2021 cohort (

Quickfall et al., 2022). Not only were these new teachers navigating the typical stressors of beginning a career in education, but they were also coping with the instability, anxiety, and resource gaps brought about by a global pandemic.

By the post-pandemic recovery period (from late 2021 onwards), emerging evidence suggested alarming levels of stress, burnout, and attrition among early-career teachers (

Education Support, 2021;

RAND Corporation, 2025). These concerns were compounded by the erosion of traditional support systems, such as mentoring and peer collaboration, due to social distancing and school closures. Many new teachers felt professionally isolated and emotionally strained, with limited opportunities to build confidence or access informal peer learning. The cumulative effect of these pressures has been an increase in contemplation of leaving the profession altogether.

The wellbeing of ECTs is not only important for individual health and satisfaction but also has broader implications for educational systems. Research has demonstrated a strong link between teacher wellbeing and outcomes such as teacher retention, instructional quality, and student achievement (

Le Cornu, 2013;

Mansfield et al., 2016). Teachers who experience chronic stress or burnout are more likely to leave the profession prematurely, contributing to ongoing teacher shortages and increased financial and human costs for school systems (

McLean et al., 2023). In classrooms, teacher stress can manifest as reduced student engagement, strained relationships, and lower academic outcomes. Moreover, when ECTs lack adequate support, it can negatively impact school culture, collegial collaboration, and the sustainability of the profession. Therefore, improving early-career teacher wellbeing is not only a matter of personal welfare but also a strategic imperative for strengthening education systems and achieving long-term reform goals.

The COVID-19 pandemic, while devastating, also highlighted the need for more resilient and responsive teacher support systems. The widespread challenges faced by ECTs revealed gaps in existing induction processes, mentoring structures, and wellbeing initiatives. At the same time, new practices such as virtual mentoring, flexible workload arrangements, and increased awareness of teacher mental health began to emerge in response to crisis conditions (

Froehlich et al., 2022;

Voss et al., 2023). These developments offer valuable insights into how systems might better support new teachers moving forward.

Given the critical role of wellbeing in teacher effectiveness and retention, examining the experiences of ECTs during this period is vital for shaping responsive education policy and workforce planning (

Wood et al., 2025;

UNESCO, 2023). Understanding both the stressors that hinder ECTs and the protective factors that help them thrive can guide targeted support measures and inform sustainable strategies for educational resilience.

This review is informed by several interrelated theoretical perspectives that underpin the core constructs examined. Wellbeing is conceptualised through the lens of Self-Determination Theory (

Deci & Ryan, 2000), which identifies autonomy, competence, and relatedness as essential psychological needs that support motivation and emotional wellbeing. Teacher stress and burnout are interpreted using the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) Model (

Bakker & Demerouti, 2007), which explains how excessive demands and insufficient resources lead to emotional exhaustion and disengagement. In contrast, the concept of resilience is informed by teacher resilience theory (

Mansfield et al., 2016), which describes the capacity of early-career teachers to adapt and thrive in the face of adversity through personal, relational, and contextual protective factors. These theoretical frameworks guide the thematic synthesis and interpretation of findings in this review.

This systematic literature review synthesises empirical research published between 2020 and 2025 on the wellbeing of early-career teachers in the post-COVID era. The review aims to (1) identify the primary stressors and challenges experienced by ECTs during and after the pandemic and (2) highlight the protective factors and support mechanisms that promote resilience and retention. By providing a thematic overview of the international evidence base, this review offers insights to guide practice, inform policy, and contribute to future research on supporting teachers at the start of their careers.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

This systematic literature review (SLR) was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines (

Rethlefsen et al., 2021), which outline rigorous criteria for systematic searches, transparent reporting, comprehensive documentation of inclusion and exclusion decisions, and structured data extraction as well as analysis processes (

Page et al., 2021). The overview of the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this SLR is summarised in

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria included empirical studies that were peer-reviewed, published in scholarly journals, written in English, and focused explicitly on early-career teacher wellbeing (teachers within their first five years in the profession) in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic or the post-pandemic recovery period. Non-empirical studies, grey literature, reviews, commentaries, or articles not specifically addressing early-career teacher populations were excluded. The initial literature search began with keyword searches across the literature, incorporating synonyms and related terms to ensure comprehensive coverage, although the detailed reporting of synonyms and related terms is beyond the scope of this section.

An initial electronic database search was performed in January 2025 using the Envisio database platform. The databases searched included Web of Science, Scopus, ERIC, and Google Scholar. The following search string was used across databases, with slight variations to adapt to platform-specific syntax:

(“early-career teacher” OR “new teacher” OR “novice teacher*” OR “beginning teacher*”) AND (“wellbeing” OR “well-being” OR “mental health” OR “burnout” OR “stress”) AND (“COVID-19” OR “pandemic” OR “post-pandemic” OR “coronavirus”)**.

The search strategy utilised combinations of keywords and Boolean operators to maximise sensitivity and specificity. Reference lists from relevant studies were manually screened to identify additional sources not captured in the initial database searches. Data collection concluded in February 2025. The title, abstract, keywords, authors’ names, journal name, year of publication, and database source for each identified record were exported into a Microsoft excel spreadsheet. Duplicate papers were then removed using this software. Eligible articles were those comprehensively and specifically related to early-career teachers (ECTs) (generally defined as within the first five years of teaching) and teacher wellbeing and/or related constructs (e.g., mental health, burnout, stress, job satisfaction) within the COVID-19 pandemic or immediate recovery period (2020–2024). Articles that focused on theory testing without primary data, or were unclear about the inclusion of ECTs, were excluded, as their main objectives did not involve the experiences of ECTs within the defined period.

2.2. Screening and Selection Process

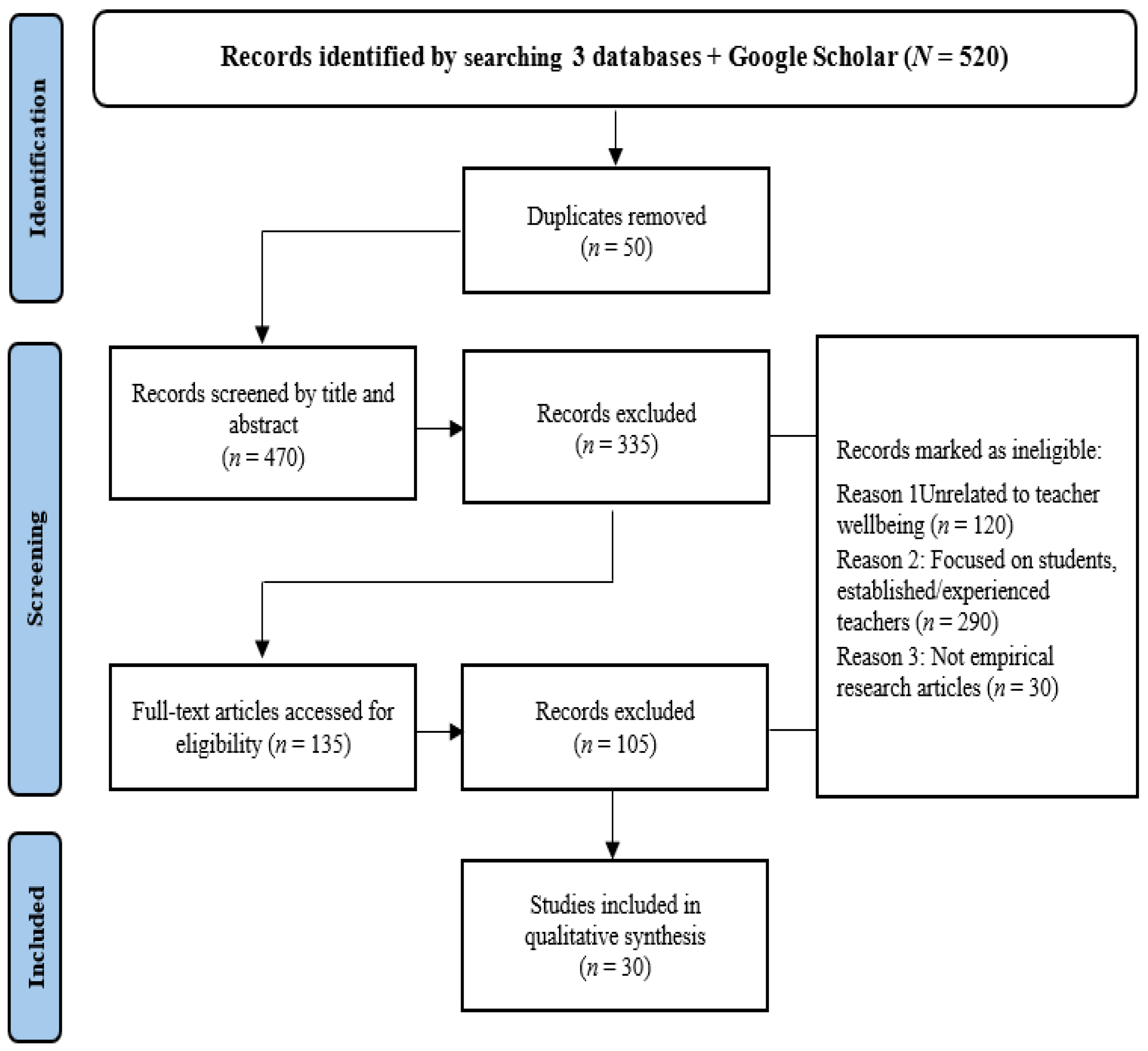

The selection process is illustrated in the flow chart below

Figure 1:

The initial database and hand searches yielded a total of 520 records. After removing 50 duplicates, 470 unique records were retained for screening. The database included metadata for each article, such as the title, abstract, keywords, authors’ names, journal name, and year of publication. All records were imported into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, which was used as the central screening and tracking tool for the review process. The spreadsheet was set up to include columns for eligibility criteria, reasons for exclusion, and reviewer notes.

The initial screening involved title and abstract review to remove studies unrelated to teacher wellbeing, those focused exclusively on students, or those that did not distinguish between early-career and experienced teachers. Following this, 30 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility against the inclusion criteria.

Reasons for exclusion at the full-text stage included lack of empirical data, no disaggregated analysis of early-career teachers, or lack of COVID-19 relevance (e.g., studies conducted pre-2020). Ultimately, 30 studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the final synthesis.

2.3. Data Analysis

For each included study, the following information was extracted into a review matrix: author(s), year of publication, country or region, participant characteristics (e.g., years of experience, education sector), research design and methodology, data collection tools, and key findings related to early-career teacher wellbeing.

Given the heterogeneity of study designs and outcomes, a narrative synthesis approach was adopted. Thematic analysis was conducted following

Braun and Clarke’s (

2006) six-phase framework: (1) familiarisation with the data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) producing the report. This structured approach ensured rigour and transparency in identifying recurring patterns across the literature.

Two overarching themes guided the analysis: (1) stressors and challenges experienced by early-career teachers during the pandemic and recovery phases; and (2) protective factors and support mechanisms that contributed to wellbeing or mitigated stress. Subthemes (e.g., workload, mentoring, and professional isolation) were generated inductively based on coded data segments. Coding was conducted independently by the researcher, and discrepancies or uncertainties in theme development were resolved through reflective discussion to ensure consistency and rigour.

Where applicable, studies were compared across contexts to identify commonalities or contextual variations. Findings were grounded in direct citations from the included literature. The authors discussed the results of the data analysis and interpretation to mitigate the potential bias of the findings.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Included Studies

The 30 studies included in this review span a range of countries, with the highest volume of research originating from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. These three countries accounted for over half of the retained publications, suggesting a strong research focus on early-career teacher wellbeing in English-speaking education systems. Additional contributions came from various European and Asian nations, though to a lesser extent. Most of the literature was published in education and psychology journals with a focus on teacher wellbeing, mental health, and professional development.

In terms of methodology, 14 studies employed quantitative methods—primarily surveys assessing variables such as stress, burnout, job satisfaction, and psychological wellbeing. Ten studies used qualitative approaches, including semi-structured interviews and open-ended survey responses to capture lived experiences. Six studies utilised mixed-method designs, combining quantitative and qualitative data to provide a more comprehensive analysis. Some longitudinal approaches were also evident, particularly in studies examining wellbeing over multiple phases of the pandemic.

Sample sizes varied significantly across studies. Quantitative studies typically included large-scale survey data from 100 to 1000+ participants. In contrast, qualitative studies often involved smaller, purposively selected samples ranging from 5 to 30 early-career teachers, allowing for in-depth exploration of personal and contextual experiences.

Several studies used theoretical or conceptual frameworks to guide their analysis, including Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory, the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model, resilience theory, and self-determination theory. These frameworks helped interpret the interaction between individual teacher characteristics and broader systemic influences on wellbeing.

Despite contextual differences, a common thread across studies was the focus on teacher wellbeing during and after the disruptions caused by COVID-19, especially for those in their first five years in the profession. Most studies collected data during 2020–2021 (the acute pandemic phase) or in 2022 as schools transitioned back to in-person instruction.

Table 2 provides a summary of the 30 studies included in the final synthesis, detailing author, country, participant characteristics, methodology, education sector, and key findings related to ECT wellbeing.

3.2. Stressors and Challenges for Early-Career Teachers Post-COVID

Of the 30 studies included in the final synthesis, 24 explicitly reported substantial challenges faced by early-career teachers (ECTs) during and after the pandemic. While many of these stressors pre-dated COVID-19, the crisis magnified their intensity or introduced new dimensions. Increased workload was one of the most frequently cited concerns, as ECTs were rapidly required to redesign lessons for online delivery, manage hybrid classrooms, and adhere to evolving safety protocols—often undertaking the equivalent of two jobs simultaneously (

Quickfall et al., 2022;

Kim et al., 2021). The abrupt transition to emergency remote teaching expanded routine tasks and demanded unfamiliar technical skills, while responsibilities such as lesson planning, grading, and tracking student engagement intensified. Even when some duties like extracurricular supervision were reduced, the steep learning curve with educational technologies and the constant shift between remote, hybrid, and in-person modes significantly elevated stress levels.

The pandemic also disrupted the professional support structures that new teachers typically rely on. Lockdowns and social distancing measures limited access to mentors and peer interactions, leaving many ECTs to begin their careers in isolation. Informal learning and emotional support opportunities—such as staffroom conversations or classroom observations—were curtailed (

Froehlich et al., 2022). One teacher shared that “social support was blocked by the digital context, and I had no idea if what I was doing was even right” (

Froehlich et al., 2022, p. 8), highlighting the emotional uncertainty brought on by diminished feedback and collaboration. Another ECT recalled that “an entire month went by, and I just felt like, why am I doing this? I almost threw in the towel at Christmas” (

Quickfall et al., 2022, p. 12), reflecting on the toll of working in isolation without timely support. In some cases, mentors had not met in person for months, further weakening vital guidance systems. This loss of support adversely impacted teacher confidence and wellbeing, with nine studies noting indicators of psychological distress, including anxiety and burnout (

Education Support, 2021).

Emotional strain and health-related concerns were common. Reports of anxiety, exhaustion, and burnout were pervasive, particularly among ECTs lacking coping routines or support systems. Compassion fatigue and personal loss—such as illness or bereavement—further compounded stress, as did negative public narratives framing teachers as resistant to remote work (

Kim et al., 2021). Many ECTs navigated overlapping roles—educator, caregiver, and parent—without clear boundaries, depleting their emotional reserves. Additionally, the pandemic created a “double transition” for many: from student-teacher to full teacher, while simultaneously adjusting to emergency teaching conditions. With practicum experiences disrupted and induction processes fragmented, 11 studies indicated that ECTs felt underprepared and less effective in the classroom (

La Velle et al., 2020).

While these figures do not represent a quantitative analysis per se, they are provided to indicate the prevalence of particular themes across the literature. This approach is consistent with a qualitative epistemological stance that values pattern recognition across diverse contexts. Surveys conducted during this period further reinforced these themes, with some indicating that up to 70% of new teachers considered leaving the profession due to cumulative stressors and dissatisfaction.

3.3. Protective Factors and Support Mechanisms

Despite these challenges, several protective factors helped ECTs cope. Induction and mentoring programs were essential in buffering pandemic stress. Extended or enhanced programs—such as the UK’s Early Career Framework—offered reduced workloads, structured mentoring, and practical guidance, which improved retention and morale (

Froehlich et al., 2022). Even virtual mentoring proved effective when mentors maintained regular, empathetic contact. Informal collegial support also played a key role: peer networks, team meetings, and leadership that encouraged collaboration and self-care fostered a sense of community. In contrast, ECTs in competitive or disconnected school cultures experienced greater isolation and stress (

Voss et al., 2023;

Quickfall et al., 2022).

Autonomy and flexibility in professional decisions emerged as another buffer against burnout and stress. ECTs who were trusted to adapt lessons or innovate with delivery methods often reported higher motivation and a greater sense of professional fulfilment. One teacher described this as “being allowed to find my voice and make real choices for my class,” which contributed to lower emotional exhaustion (

Pressley et al., 2021). When autonomy was combined with supportive mentoring or collegial input, it boosted confidence and professional agency. However, as noted by

Froehlich et al. (

2022), autonomy without guidance could be “a double-edged sword,” leaving some ECTs overwhelmed. Personal coping skills and emotional competencies also played a central role in shaping resilience. Teachers who engaged in self-care, set clear work–life boundaries, or reframed their difficulties as growth opportunities experienced better wellbeing outcomes. One study participant explained that “I had to learn to protect my energy and ask for help before burnout hit” (

Wang et al., 2022). Some schools actively supported these capacities through mental health professional development or targeted resilience training (

Alves et al., 2020).

Leadership support was crucial. Clear communication, fair evaluation policies, and the provision of resources (e.g., PPE, aides, planning time) helped reduce anxiety. Empathetic principals who acknowledged ECT challenges and adjusted expectations significantly improved morale. One study captured this sentiment with a participant reflecting that “our principal checked in every week, not just about teaching, but about how we were coping” (

Sultana & Aurangzeb, 2022). In contrast, several ECTs in unsupportive environments noted feeling “completely invisible” or “left to sink or swim” (

Coates et al., 2020), which exacerbated stress and isolation. Targeted wellbeing initiatives—such as counselling access, peer support groups, or wellbeing-focused PD—were also effective. Programs that explicitly addressed emotional regulation and professional identity formation led to higher retention and positive feedback (

Le Cornu, 2013). As one teacher described, “just knowing wellbeing was on the agenda made me feel valued” (

Wang et al., 2022). A shift in mindset was evident: teacher wellbeing began to be seen as a capacity to build, not just an individual responsibility.

Although the post-COVID period brought immense stress, early-career teachers were not without support. Strong induction, mentoring, collegial connection, balanced autonomy, coping skills, and responsive leadership together formed a protective web. The literature affirms a clear takeaway: new teachers thrive when they feel supported, connected, and equipped—even in times of crisis.

4. Discussion

This systematic review confirms that the COVID-19 pandemic deepened pre-existing wellbeing challenges for early-career teachers (ECTs). The early years of teaching have long been recognised as emotionally and professionally demanding (

Ingersoll, 2012;

Mansfield et al., 2016), but the pandemic introduced unprecedented layers of complexity. ECTs across multiple international settings reported heightened workloads, emotional exhaustion, and professional uncertainty (

Kim et al., 2021;

Pressley et al., 2021). A recurring theme was the erosion of job satisfaction and increased contemplation of leaving the profession. These global trends reinforce the need for systemic, sustained support to safeguard this vulnerable cohort during times of disruption and beyond.

Consistent with previous literature, this review affirms the benefits of robust support mechanisms for ECTs—particularly in crisis contexts. While structured induction and mentoring programs have long demonstrated positive impacts on efficacy and retention (

Smith & Ingersoll, 2004), the pandemic illuminated just how essential these systems are. Teachers who accessed sustained professional networks, leadership guidance, or clear wellbeing policies generally fared better. One notable example is the two-year induction model introduced in the UK, which was associated with improved teacher confidence and reduced attrition. In contrast, countries without formal induction structures saw greater distress among ECTs. These contrasts point to the urgent need for equity in support provision and policy standardisation across education systems.

The pandemic prompted both disruption and innovation in early-career teacher support. While traditional induction structures were strained, new approaches—such as virtual mentoring and flexible autonomy—emerged as important protective factors. These innovations often originated from schools where leadership was empathetic, communicative, and responsive. Evidence suggests that such environments foster relational trust and professional resilience (

Bryk & Schneider, 2002). For long-term impact, leadership development initiatives should embed wellbeing-focused strategies that extend beyond emergency measures and become core to everyday school practice.

The experiences of ECTs during the pandemic have brought renewed attention to systemic mental health challenges in teaching. Their heightened vulnerability spotlighted longstanding stressors—such as excessive workloads and limited autonomy—that affect the broader teaching profession. At the same time, the crisis stimulated novel practices, including digital peer collaboration and streamlined administrative processes, which warrant further exploration. Embedding these adaptive strategies into school structures could support the emotional and professional sustainability of teaching across all career stages.

Early-career attrition remains a critical policy concern, now exacerbated by the additional stressors brought on by COVID-19. Nonetheless, this review reinforces the idea that attrition is preventable when appropriate supports are in place. Emotional and practical resources—combined with professional autonomy—can significantly bolster retention (

McLean et al., 2023). These findings align with theories of self-determination and occupational wellbeing, which suggest that meeting core psychological needs enhances teacher motivation and resilience (

Deci & Ryan, 2000;

Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2017).

Although global patterns emerged in the data, country-specific differences were notable. In systems with pre-existing, well-funded induction programs, ECTs generally reported greater access to guidance and stability. In contrast, contexts with limited investment in new teacher support saw more pronounced disruptions. These contrasts highlight systemic inequities and suggest that wellbeing cannot be addressed in isolation from broader educational policy. Future research comparing national responses to ECT wellbeing during the pandemic could offer valuable guidance for cross-context learning and reform.

This review identifies several key directions for future inquiry. Longitudinal studies are essential to trace how pandemic-era induction experiences have influenced teacher development and retention over time. Greater attention should also be paid to underrepresented sectors—such as early childhood, vocational, and tertiary education—where the impacts on ECTs remain underexplored. Additionally, there is a need for intervention-based research to evaluate the effectiveness of specific wellbeing initiatives. Including grey literature and practitioner-led reports could help capture the evolving and often informal innovations implemented during the pandemic.

The findings of this review highlight the urgency of integrating well-being-focused strategies into early-career teacher policy and practice. The pandemic served as both a stress test and a catalyst, revealing the vulnerabilities in induction systems while also showcasing the potential of adaptive, relational support. Building resilience in the teaching workforce begins with recognising and investing in the wellbeing of those at the very start of their careers.

5. Conclusions

Early-career teacher wellbeing in the post-COVID-19 era is a critical priority for educational recovery and workforce sustainability. This systematic review synthesised empirical research from 2020 to February 2025 and found that early-career teachers experienced heightened stress, professional isolation, and emotional fatigue during the pandemic. Additionally, it also identified protective factors—comprehensive induction programs, mentoring, collegial networks, and leadership support—that mitigated adverse outcomes and promoted resilience.

The findings underscore the urgent need for education systems to embed structural supports for early-career teachers. Rather than reverting to pre-pandemic norms, schools and policymakers should institutionalise the successful innovations born from crisis. These include extended induction models, virtual mentoring frameworks, and whole-school wellbeing initiatives. School leaders play a central role and must be equipped to cultivate environments that foster psychological safety, professional growth, and a sense of belonging.

To strengthen the evidence base and guide sustainable support strategies for early-career teachers, future research should focus on several key areas. Longitudinal studies are needed to track teachers who entered the profession during the COVID-19 pandemic, providing insight into the lasting effects on their wellbeing, professional identity, and retention. Further investigation into underrepresented sectors—such as early childhood education, vocational training, and non-traditional teaching contexts—could reveal unique challenges and support needs that are currently underexplored. Additionally, there is a pressing need for intervention-based research that evaluates the effectiveness of specific support mechanisms, including mentoring programs, wellbeing-focused professional development, and resilience training, ideally through experimental or mixed-method designs. Comparative policy studies examining how different countries responded to the needs of early-career teachers during the pandemic would also yield valuable insights, enabling the identification of scalable and context-sensitive strategies for global education systems. Together, these directions can inform more responsive, equitable, and enduring approaches to teacher induction and support.

By building on the lessons of the pandemic, education systems have an opportunity to reshape how early-career teachers are supported. Prioritising their wellbeing is not just a moral imperative—it is a strategic investment in teaching quality, student outcomes, and the future of the profession.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, T.D.; methodology, T.D.; validation, T.D.; formal analysis, T.D. and E.P.; investigation, T.D.; resources, T.D.; data curation, E.P.; writing—original draft preparation, T.D.; writing—review and editing, T.D. and E.P.; visualisation, T.D.; supervision, T.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ECT | Early-career teacher |

| NQT | Newly-qualified teacher |

References

- Allen, R., Jerrim, J., & Sims, S. (2020). How did the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic affect teacher wellbeing? Centre for Education Policy and Equalising Opportunities (CEPEO). Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:ucl:cepeow:20-15 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Alves, R. F., Precioso, J. A. G., & Becona, E. (2020). Well-being and health perception of university students in Portugal: The influence of parental support and love relationship. Health Psychology Report, 8(2), 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryk, A. S., & Schneider, B. L. (2002). Trust in schools: A core resource for improvement. Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Coates, B., Cowgill, M., Chen, T., & Mackey, W. (2020, April). Shutdown: Estimating the COVID-19 Employment Shock. Grattan Institute Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Education. (2021). Induction for early career teachers (England)—COVID-19 response. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/induction-for-early-career-teachers-england (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Education Commission of the States. (2021). Supporting early-career teachers beyond the pandemic. Available online: https://www.ecs.org/3-ways-to-support-early-career-teachers-beyond-the-covid-19-pandemic/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Education Support. (2021). Teacher wellbeing index 2021. Available online: https://www.educationsupport.org.uk/media/qzna4gxb/twix-2021.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Froehlich, D. E., Schmitt, C., & Harteis, C. (2022). Newly qualified teachers’ well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: Testing a social support intervention. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 873797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, K. C., Reinke, W. M., & Eddy, C. L. (2021). Teacher stress and burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: Patterns and protective factors. School Psychology, 36(6), 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll, R. M. (2012). Beginning teacher induction: What the data tell us. Phi Delta Kappan, 93(8), 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B., Down, B., Le Cornu, R., Peters, J., Sullivan, A., Pearce, J., & Hunter, J. (2012). Early career teachers: Stories of resilience. University of South Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, L. E., Leary., R., & Asbury, K. (2021). Teachers’ narratives during COVID-19 partial school reopening: An exploratory study. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 50(3), 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S. S. S., Shum, E. N. Y., Man, J. O. T., Cheung, E. T. H., Amoah, P. A., Leung, A. Y. M., Okan, O., & Dadaczynski, K. (2022). Teachers’ well-being and associated factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study in Hong Kong, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 14661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Velle, L., Newman, S., Montgomery, C., & Hyatt, D. (2020). Initial teacher education in England and the COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46(4), 596–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Cornu, R. (2013). Building early career teacher resilience: The role of relationships. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 38(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, C. F., Beltman, S., Broadley, T., & Weatherby-Fell, N. (2016). Building resilience in teacher education: An evidence-informed framework. Teaching and Teacher Education, 54, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, D., Worth, J., & Danechi, S. (2023). The progression and retention of teach first teachers. National Foundation for Educational Research. Available online: https://www.nfer.ac.uk/media/v5jmvos0/the_progression_and_retention_of_teach_first_teachers.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 134, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pressley, T., Ha, C., & Learn, E. (2021). Teacher stress and anxiety during COVID-19: An empirical study. School Psychology, 36(5), 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quickfall, A., Arthur, L., & Brown, A. (2022). The experiences of newly qualified teachers in 2020 and what we can learn for future cohorts. London Review of Education, 21(1), 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RAND Corporation. (2025). 2024 RAND annual report (Corporate Publication No. CP-A1065-5). RAND Corporation. Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/corporate_pubs/CPA1065-5.html (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Rethlefsen, M. L., Kirtley, S., Waffenschmidt, S., Ayala, A. P., Moher, D., Page, M. J., & Koffel, J. B. (2021). PRISMA-S: An extension to the PRISMA statement for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2017). Still motivated to teach? A study of school context variables, stress, and job satisfaction among teachers in senior high school. Social Psychology of Education, 20(1), 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T. M., & Ingersoll, R. M. (2004). What are the effects of induction and mentoring on beginning teacher turnover? American Educational Research Journal, 41(3), 681–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, N., & Aurangzeb, W. (2022). Effect of job stress on job burnout of early childhood education teachers. Journal of Educational Research, 25(2), 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2023). Global report on teachers: Addressing teacher shortages and transforming the profession. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/global-report-teachers-addressing-teacher-shortages-and-transforming-profession (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Voss, T., Klusmann, U., Bönke, N., Richter, D., & Kunter, M. (2023). Teachers’ emotional exhaustion and teaching enthusiasm before versus during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from a long-term longitudinal study. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 231(2), 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Lee, S. Y., & Hall, N. C. (2022). Coping profiles among teachers: Implications for emotions, job satisfaction, burnout, and quitting intentions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 68, 102030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, P., Quickfall, A., & Clarke, E. (2025). Exploring the well-being of early career teachers: Staying afloat whilst fixing the boat during COVID-19. Practice, 7, 153–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).