A Methodological Route for Teaching Vocabulary in Spanish as a Foreign Language Using Oral Tradition Stories: The Witches of La Jagua and Colombia’s Linguistic and Cultural Diversity

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Oral Tradition Stories and Literary Texts in SFL Classrooms

1.2. Foreign Language Policy and Teaching Materials in Colombian SFL Classrooms

2. Method

2.1. Conceptual Framework for Didactic Materials

2.2. Material Type and Design

2.3. Vocabulary Learning Methodology

- The identification of the lexical form;

- The comprehension/interpretation of meaning;

- The use of the word in meaningful contexts;

- Retention in short-term memory;

- Fixation in long-term memory;

- Reuse through cognitively demanding and communicative tasks.

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions: Toward an Intercultural Approach to SFL Teaching

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SFL | Spanish as a Foreign Language |

| L2 | Second/Foreign Language |

| 1 | Caficultores are also known as campesinos in Colombia. While the English translation would be “farmers,” I do not believe this term fully encapsulates the essence of what caficultores represent in Colombian society. Therefore, I have retained the original Spanish term. |

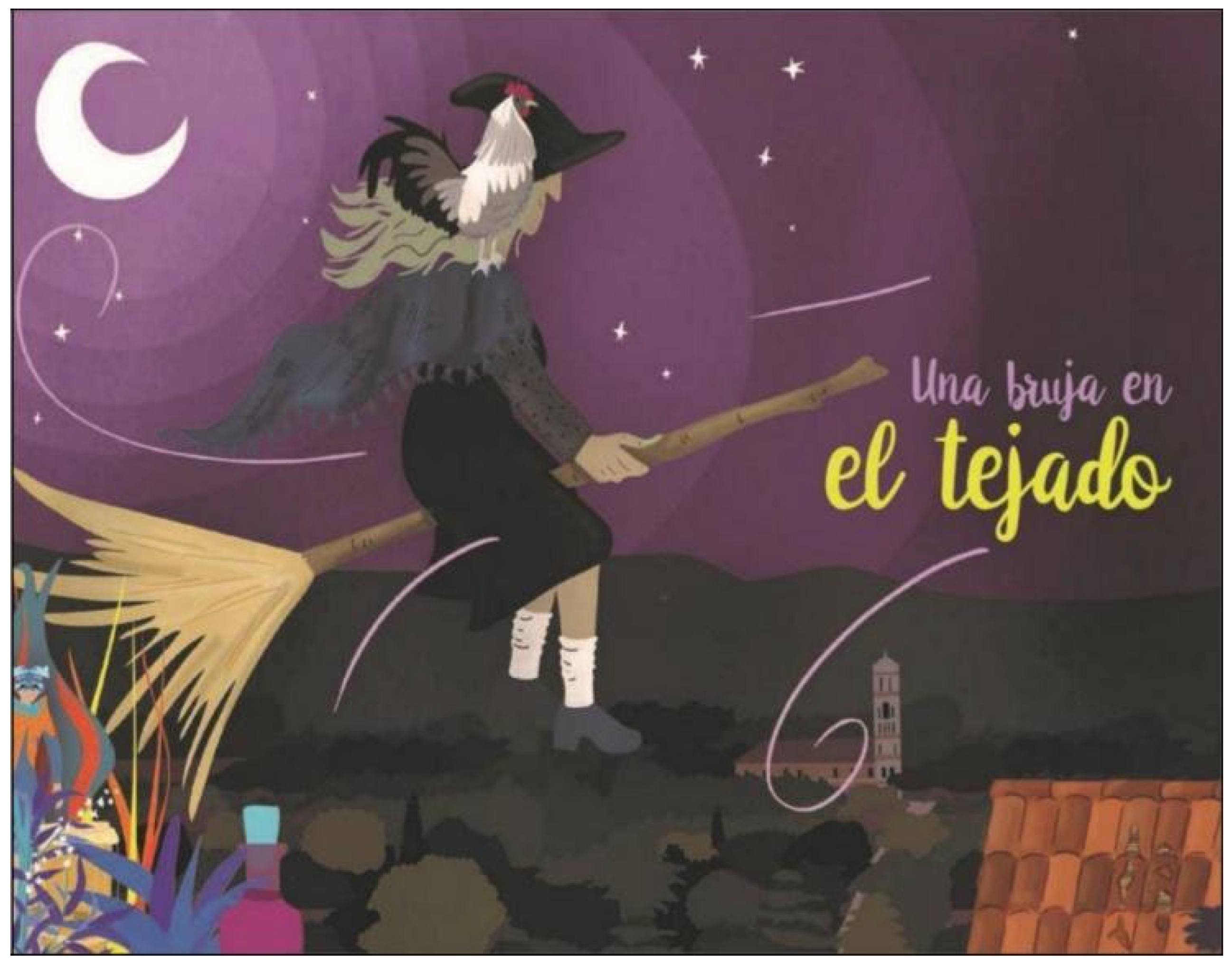

| 2 | Una bruja en el tejado was published by www.colombia.co, the official country brand platform managed by ProColombia. It is part of a digital collection of micro-stories created to promote Colombian regional culture, folklore, and creative writing. These stories highlight local legends and traditions as a way to share Colombia’s cultural diversity with both national and international audiences. |

References

- Abenójar Sanjuán, Ó. (2012). La literatura oral en el aula de español: Aplicaciones didácticas de la tradición y el folclore. Actas del III Simposio Internacional de Didáctica de Español para Extranjeros, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, E. (1994). ¿Cómo ser profesor/a y querer seguir siéndolo? (10th ed.) Edelsa Grupo Didascalia, S.A. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, G. D. S. (2022). Apreciaciones en torno al carácter universal de las leyendas orales: Una mirada a partir de la realidad amazónica brasileña. Caligrama: Revista de Estudos Românicos, 27(2), 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baquero Montoya, Á., & De la Hoz Siegler, A. (2010). Cultura y tradición oral en el caribe colombiano: Propuesta pedagógica para incorporar la investigación. Ediciones Uninorte. [Google Scholar]

- Baralo, M. (2003). Analizar materiales desde una perspectiva psicolingüística: ¿qué aprendemos y con qué? XII Encuentro Práctico de Profesores ELE, Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- Barcroft, J. (2015). Lexical input processing and vocabulary learning. John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera Torres, L. Z., Zuluaga Molina, J. F., & Flórez García, M. M. (2022). La oferta de formación académica virtual en el área de español para hablantes de otras lenguas en Colombia: Realidades y retos. Lingüística y Literatura, 43(82), 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaner, P. (2017). Enseñar léxico en el aula de español: El poder de las palabras (F. Herrera, & N. Sans, Eds.). Difusión. [Google Scholar]

- Baudi, I., García, E. S., & Moyanno, N. C. (2023). CLIL and critical thinking through literature: Activities on poems about argentina’s military dictatorship. Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning, 15(2), e1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal León, D. M., Caro, Y. A., Rodríguez Ochoa, O., Jaramillo Cardona, G., & Gómez Salazar, J. O. (2020). Estado de la cuestión de los recursos didácticos en los programas del español como lengua extranjera (ELE) en Bogotá y Medellín. Revista Interamericana de Investigación, Educación y Pedagogía, RIIEP, 13(1), 63–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderón Álvarez, L. F. (2022). Reflexiones sobre tradición oral en el aula. Educación y Ciencia, 26, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cariou, W. (2020). Terristory: Land and language in the indigenous short story—Oral and written. Commonwealth Essays and Studies, 42(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, D., & Guerrero, C. H. (2024). Traces of coloniality in Colombia’s linguistic landscape: A multimodal analysis of language centers’ English advertisements. Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada, 24(2), e21526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pablos-Ortega, C. (2018). Análisis y diseño de materiales didácticos. In J. Muñoz-Basols, E. Gironzetti, & M. Lacorte (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of Spanish language teaching (1st ed., pp. 80–93). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Barriga, Á. (2013). Guía para la elaboración de una secuencia didáctica. Comunidad de conocimiento UNAM. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, R., Skehan, P., Shaofeng, L., Shintani, N., & Lambert, C. (2019). Task-based language teaching: Theory and practice. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, T. H. (2016). Overheating: An anthropology of accelerated change. Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Estaire, S. (2007). Tareas para reciclar el léxico y ampliar sus redes asociativas. Actas Del Programa de Formación Para Profesorado de Español Como Lengua Extranjera 2006–2007, 400–413. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Vítores. (2023). El español en el mundo. Instituto Cervantes. [Google Scholar]

- Fuertes Gutiérrez, M., Márquez Reiter, R., & Moreno Clemons, A. (2023). Descolonización y enseñanza del español. Journal of Spanish Language Teaching, 10(2), 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Barajas, M. T., Kaplan Navarro, J. C., Reyes Osua, G., & Reyes Osua, M. A. (2010). La secuencia didáctica, herramienta pedagógica del modelo educativo ENFACE. Universidades, 46, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Molina, J. R. (2004). Los contenidos léxico-semánticos. In J. Sánchez Lobato, & I. Santos Gargallo (Eds.), Vademécum para la formación de profesores. Enseñar español como segunda lengua (L2)/lengua extranjera (LE). Sociedad general española de librerías, S.A. SGEL. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Molina, J. R. (2005). Las unidades léxicas del español. Carabela, 56, 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Guarín, D. (2018). Léxico: Una aproximación conceptual. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329427452_Lexico_una_aproximacion_conceptual (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Guarín, D. (2022). Colombian literature in the Spanish as a foreign language’s textbooks: (Re)Presentations, uses and perspectives. Visitas Al Patio, 16(2), 460–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarín, D., & Arias-Cortés, D. (2025). English as symbolic capital: Globalization and the linguistic landscape of Armenia, Quindío (Colombia). Languages, 10(3), 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, G. (2017). Exploring English language teaching: Language in action (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hauy, M. E. (2014). Lectura literaria: Aportes para una didáctica de la literatura. Zona Próxima, 20, 22–34. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/853/85331022003.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Hibbin, R. (2016). The psychosocial benefits of oral storytelling in school: Developing identity and empathy through narrative. Pastoral Care in Education, 34(4), 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelin, E. (2012). Los trabajos de la memoria (2nd ed.). Instituto de Estudios Peruanos. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Calderón, F. J., & Sánchez Rufat, A. (2017). Posibilidades de aplicación de un enfoque léxico a la enseñanza comunicativa del español. In N. Caballero (Ed.), Nuevas aportaciones al estudio de la enseñanza y aprendizaje de lenguas (pp. 12–23). Universidad de Extramadura. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10662/5263 (accessed on 16 August 2018).

- Lane, P., & Makihara, M. (2017). Indigenous peoples and their languages. In O. García, N. Flores, & M. Spotti (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of language and society (pp. 299–320). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licata, G., Austin, T., & Moreno Clemons, A. (2023). Raciolinguistics and Spanish language teaching in the USA: From theoretical approaches to teaching practices. Journal of Spanish Language Teaching, 10(2), 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, G., & Ruíz Campillo, J. P. (2009). Criterios para el diseño y la evaluación de materiales comunicativos. Didáctica del Español como Lengua Extranjera, Colección Expolingua, Madrid. Reedición en MarcoELE, 9(2009), 127–155. [Google Scholar]

- Mercado-López, L. M. (2018). Entre tejana y chicana: Tracing Proto-chicana identity and consciousness in tejana young adult fiction and poetry. In L. Alamillo, L. M. Mercado-López, & C. Herrera (Eds.), Voices of resistance: Interdisciplinary approaches to chican@ children’s literature (pp. 3–15). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Educación Nacional. (2006). Formar en lenguas extranjeras: Inglés !el reto! Available online: https://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1621/articles-115174_archivo_pdf.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2022).

- Mishan, F., & Kiss, T. (2024). Developing intercultural language materials (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishan, F., & Timmis, I. (2015). Materials development for TESOL. Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Munévar Salazar, A., Chaparro Rojas, L. A., & Bernal Chávez, J. A. (2022). Cuando las brujas vuelan y hacen daño. Esquemas culturales sobre la brujería del campesinado en Colombia. LiminaR. Estudios Sociales y Humanísticos, 20(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nation, I. S. P. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pasuy Guerrero, G. Y., Isaza Ramírez, V., & Salgado Acosta, L. (2022). Tradición oral: Material auténtico para el viaje intercultural entre Colombia y Brasil. In G. Y. Pasuy Guerrero, & M. C. Silva Agudelo (Eds.), Enseñanza, lengua y cultura en ELE (pp. 21–39). Sello Editorial Universidad de Caldas. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce-Naranjo, G., & Villanueva Roa, J. d. D. (2023). Educación inclusiva, justicia social y literatura de tradición oral. Escritos, 31(66), 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido Rodríguez, C. (2021). La enseñanza del léxico. In N. Agray-Vargas (Ed.), Investigación y formación de docentes en español como lengua extranjera. Editorial Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, J. C. (2005). Materials development and research—Making the connection. RELC Journal, 37(1), 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J. C., & Rodgers, T. S. (2014). Approaches and methods in language teaching (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Risager, K., & Fernández, S. S. (2024). Analizar las representaciones culturales en manuales de español desde perspectivas transnacionales y decoloniales. Journal of Spanish Language Teaching, 11(2), 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, L., Baquero, S., & Valencia, A. (2024). Orientaciones para el diseño de material didáctico para la enseñanza del español como segunda lengua a comunidades indígenas. Lenguaje, 52(2S), e20513575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Vásquez, N. F. (2020). El español de Colombia. Nueva propuesta de división dialectal. Lenguaje, 48(2), 160–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauer, G. A. (2024). Intercultural competence and pragmatics (1st ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, A. (2024). Reclaiming the feminine in cities at war: Female agency, spatial subversion, and linguistic resistance in women-authored literature. Studia Rossica Posnaniensia, 49(1), 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tecedor, M. (2024). A social justice approach to develop intercultural communicative competence. Journal of Spanish Language Teaching, 11(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, B. (2011). Materials development in language teaching (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, B. (2012). Materials development for language learning and teaching. Language Teaching, 45(2), 143–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, B., & Masuhara, H. (2018). The complete guide to the theory and practice of materials development for language learning. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Velez-Rendon, G. (2003). English in Colombia: A sociolinguistic profile. World Englishes, 22(2), 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veliz, L., Díaz, A. R., & Heinrichs, D. H. (2024). Introduction to the special issue: Pluriversalizing the teaching and learning of Spanish. Critical Multilingualism Studies, 11(2), i–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, C. E. (2018). Interculturality and Decoloniality. In W. D. Mignolo, & C. E. Walsh (Eds.), On decoloniality: Concepts, analytics, praxis (pp. 57–80). Duke University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyers, J. R. (2016). English shop names in the retail landscape of Medellín, Colombia: How English denotes prosperity and status in a recently transformed city. English Today, 32(2), 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata Morales, J. F. (2010). Oralidad y escritura en la trova antioqueña. Lingüística y Literatura, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuluaga Molina, J. F., & Gómez Medina, J. (2024). Enseñanza, promoción y aprendizaje del español como lengua adicional en Colombia. Lenguaje, 52(2S), 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

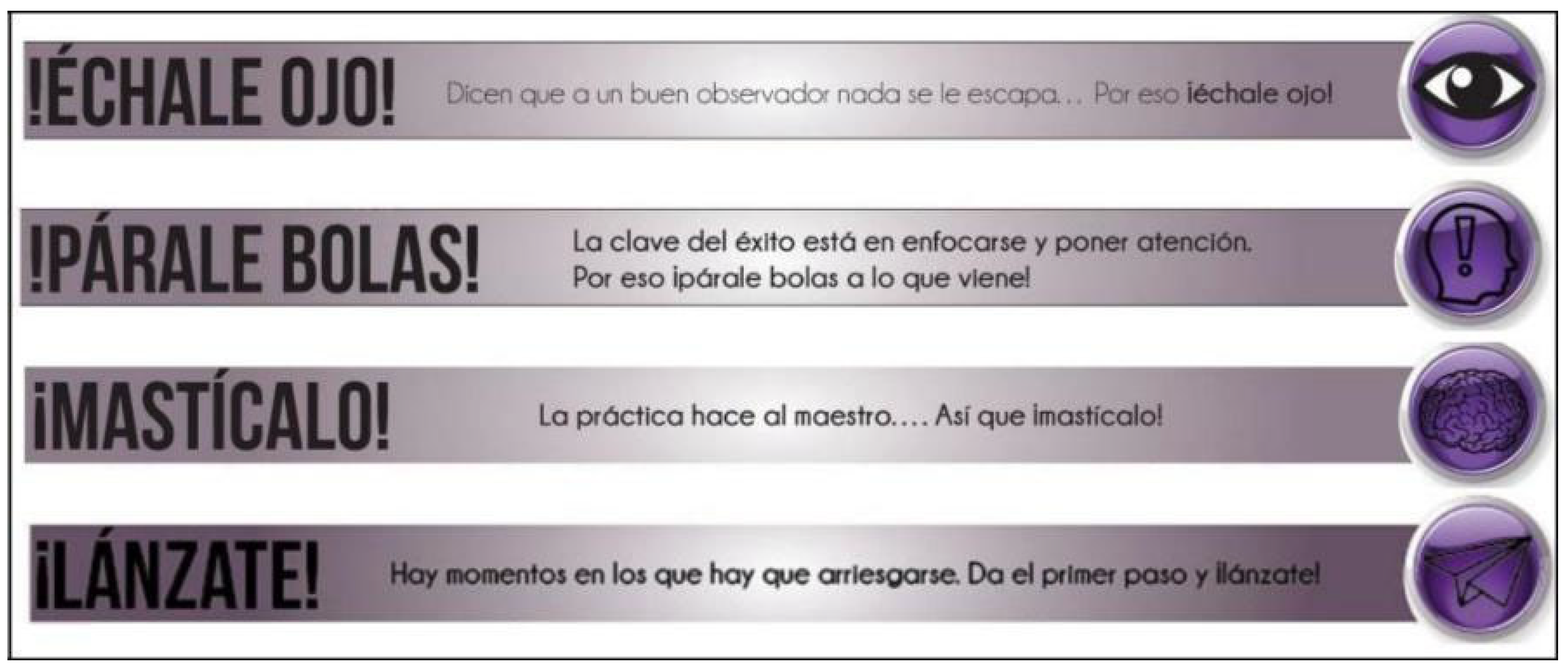

| Cognitive Process | Didactic Section | Description/Translation |

|---|---|---|

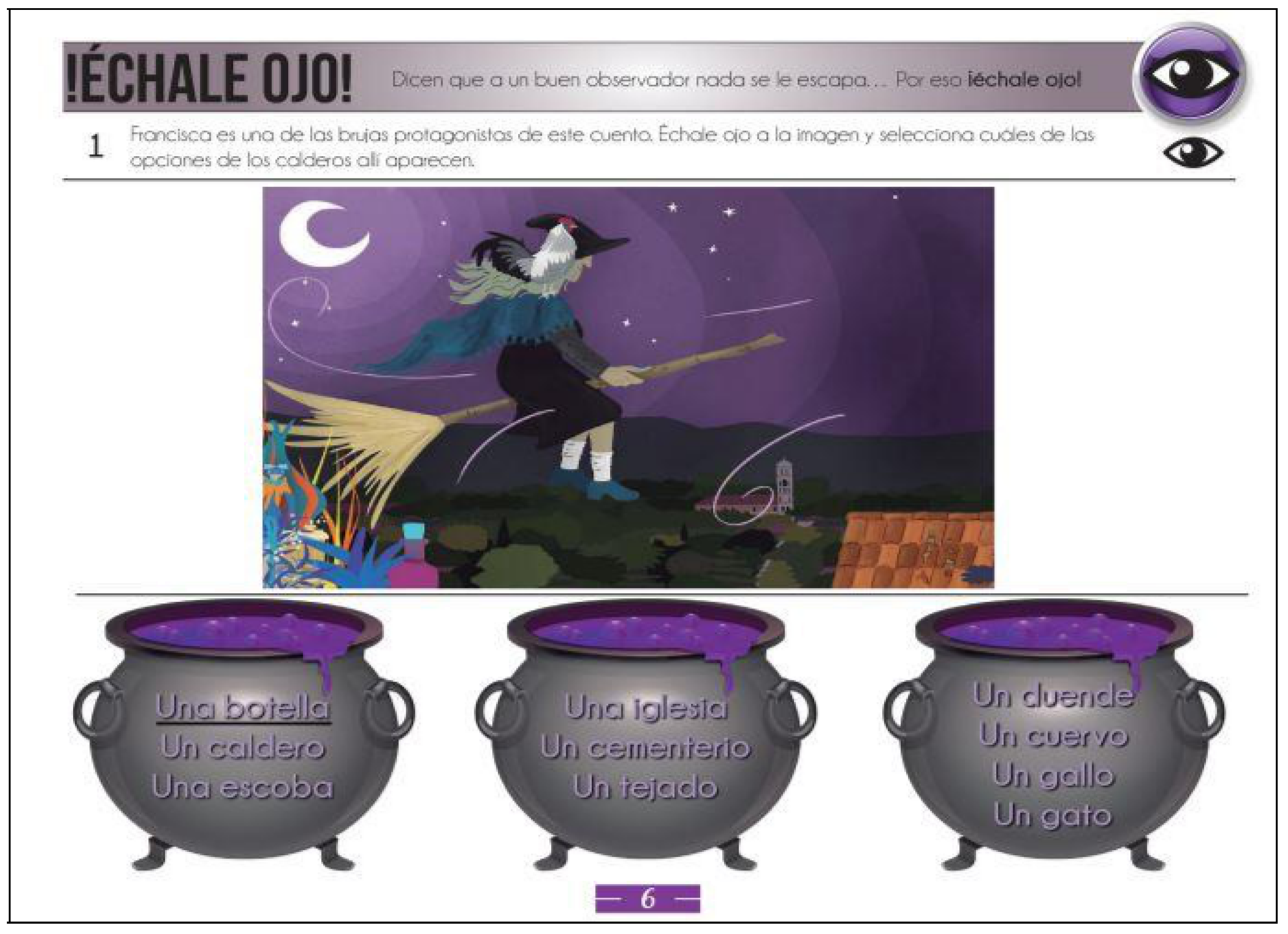

| (a) Identification | ¡Échale ojo! | “Check it out”—Initial recognition of lexical items |

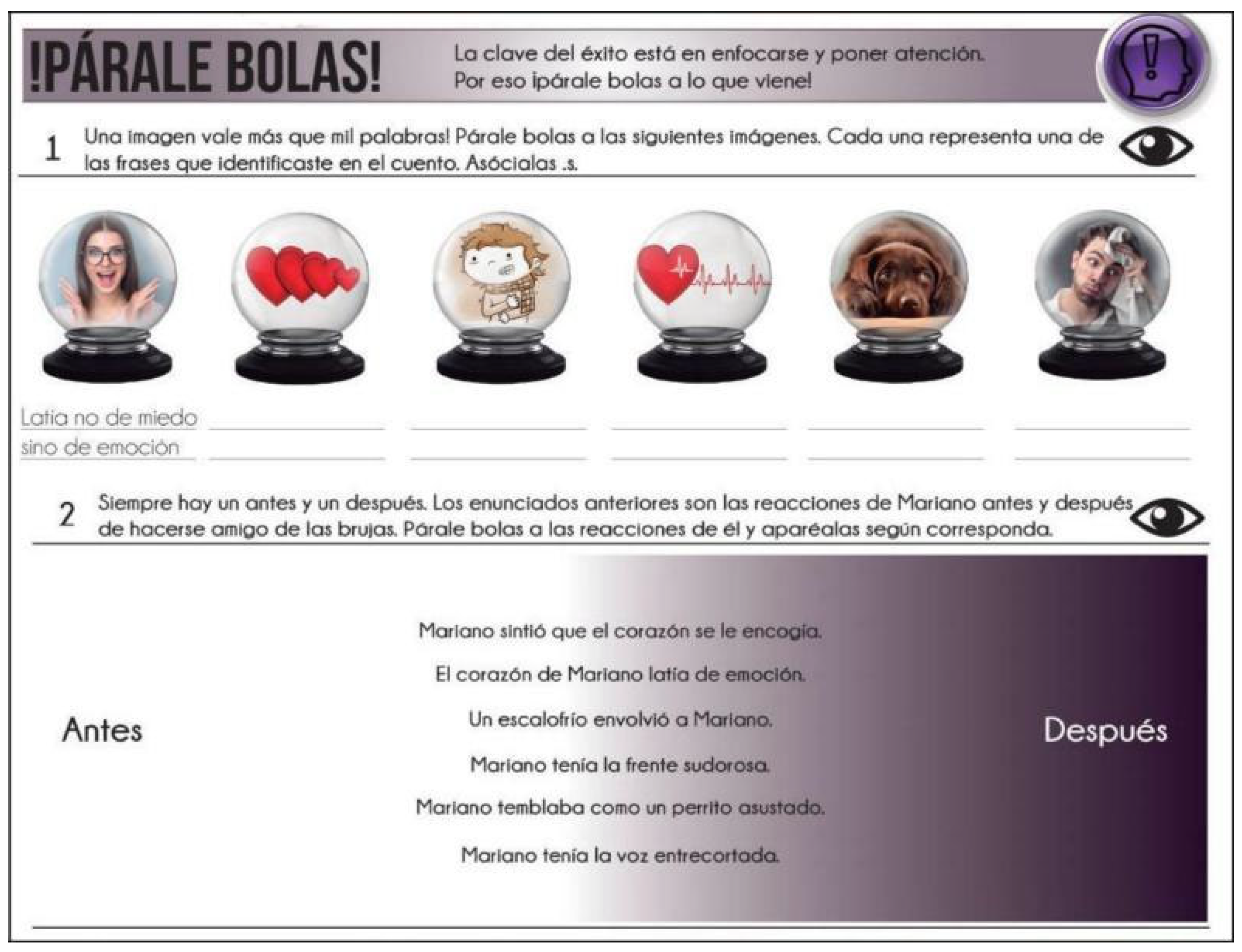

| (b) Comprehension/ Interpretation | ¡Párale bolas! | “Pay attention”—Understanding and interpreting lexical meaning |

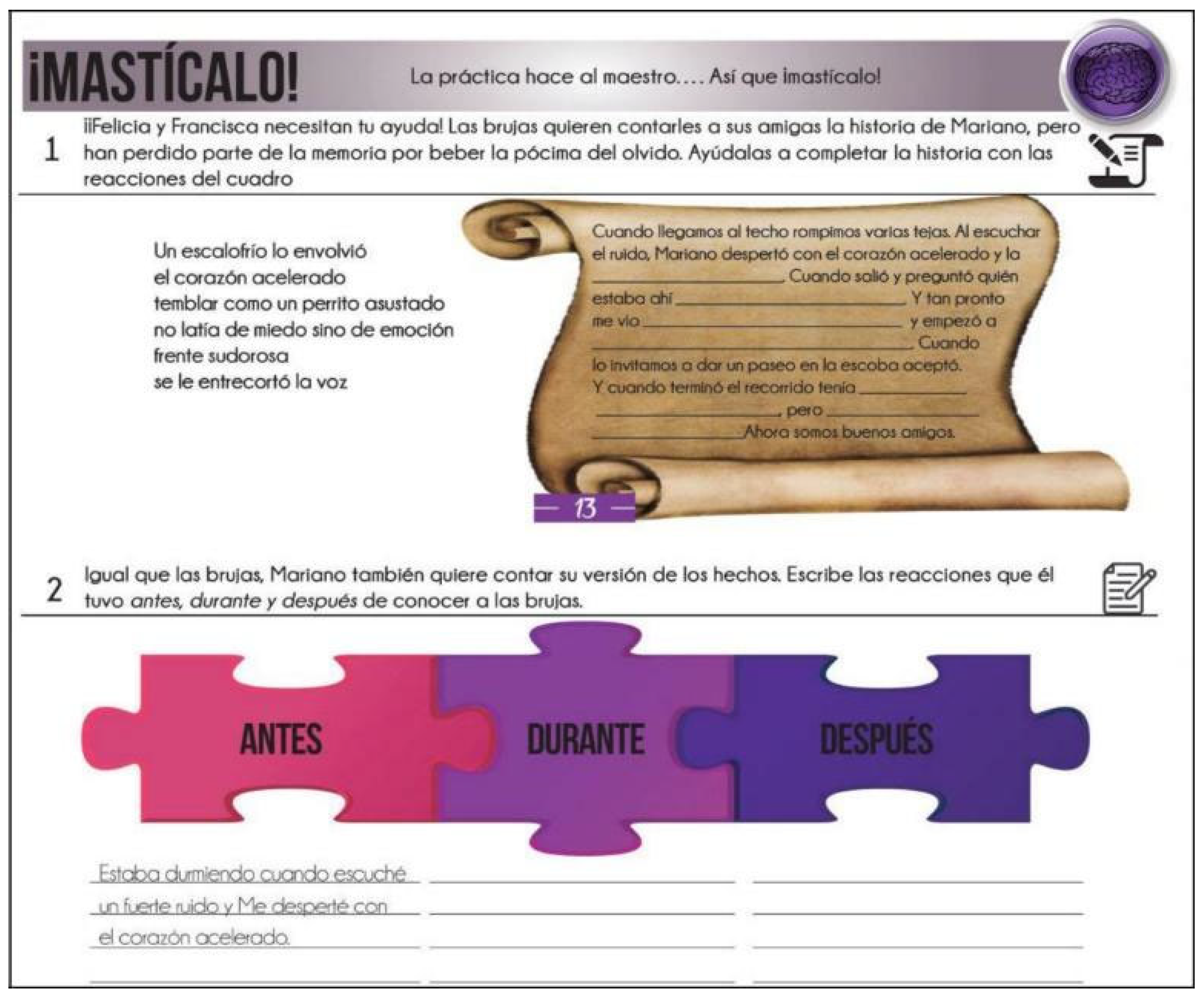

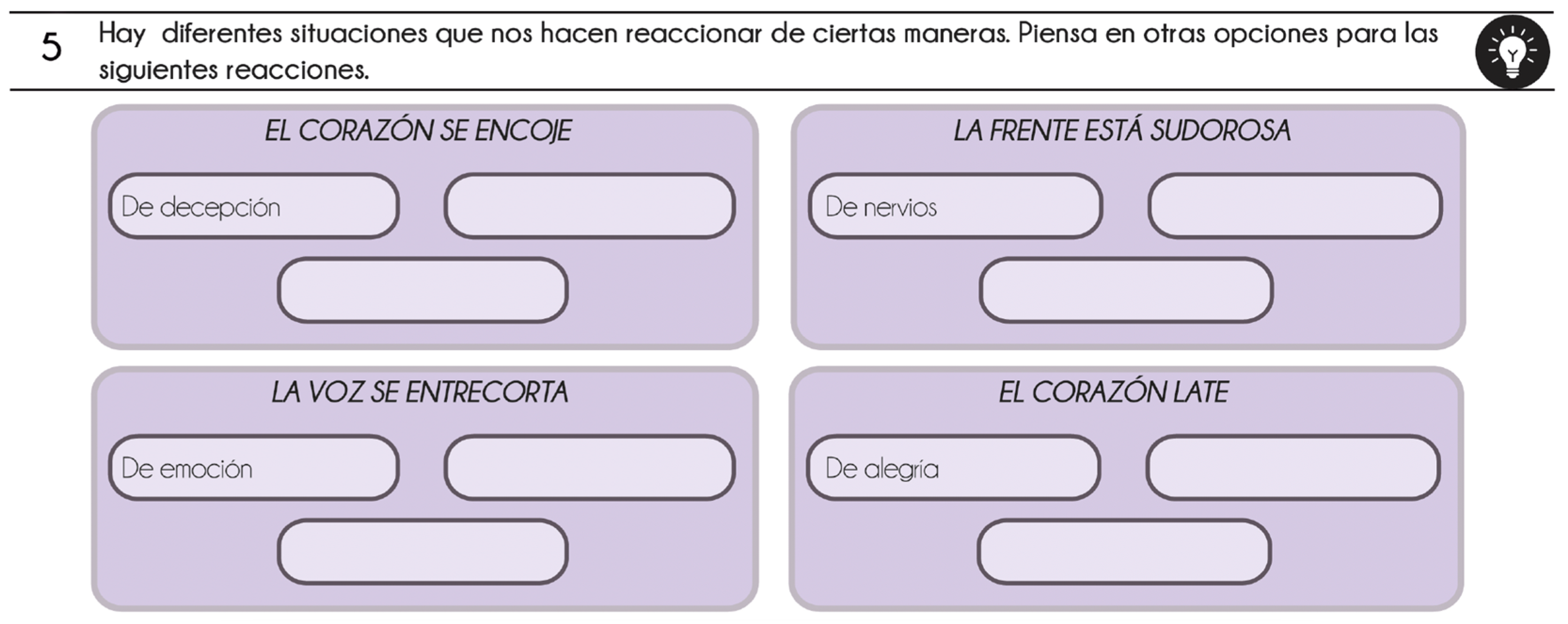

| (c) Utilization | ¡Mastícalo! | “Chew on it”—Guided practice and manipulation in context |

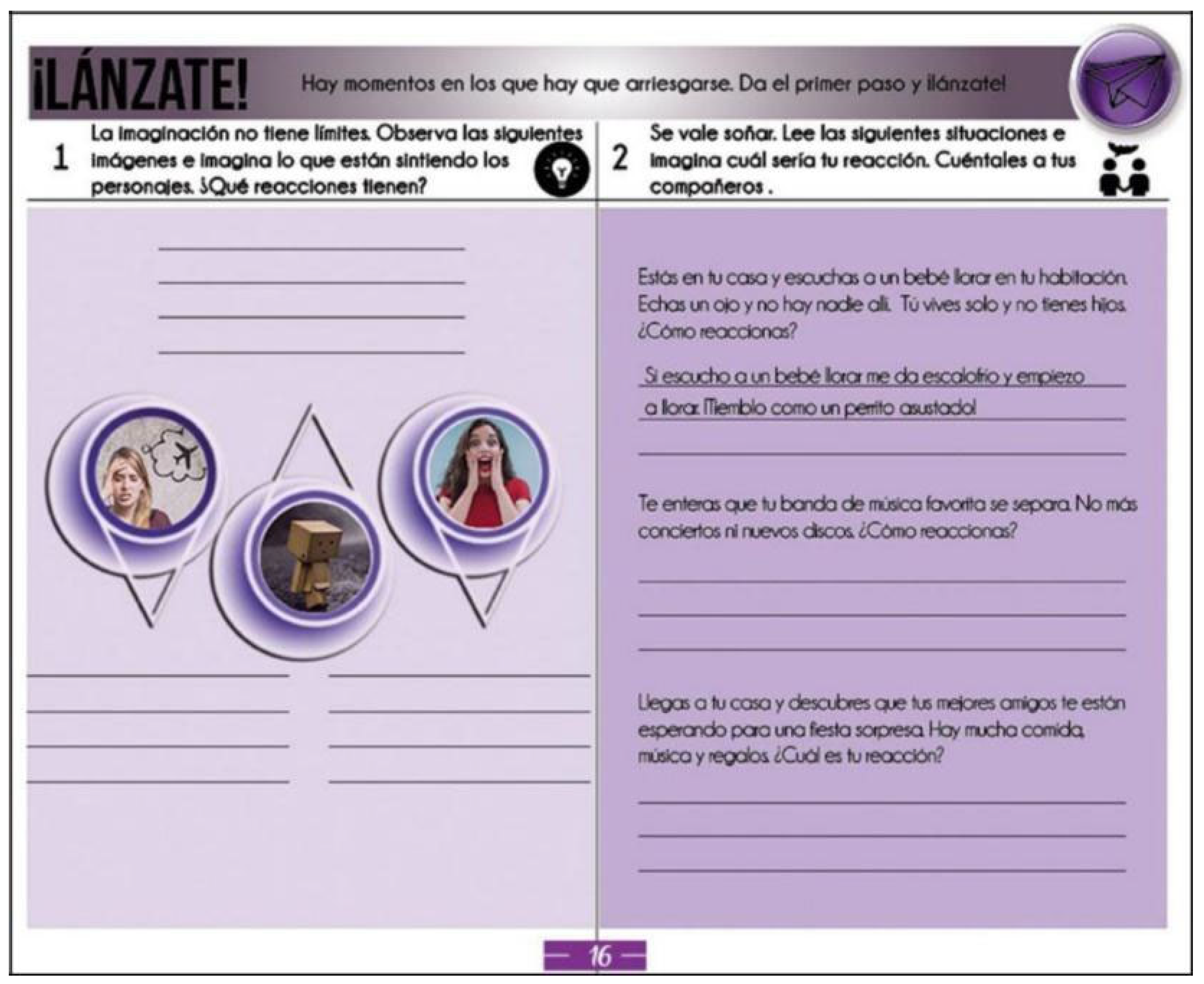

| (d) Retention | ¡Lánzate! | “Go for it”—Active use to consolidate memory |

| (e) Fixation | ||

| Reflexiona | “Reflect on it”—Metacognitive reflection and self-evaluation (not part of original cognitive model) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guarín, D. A Methodological Route for Teaching Vocabulary in Spanish as a Foreign Language Using Oral Tradition Stories: The Witches of La Jagua and Colombia’s Linguistic and Cultural Diversity. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 949. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15080949

Guarín D. A Methodological Route for Teaching Vocabulary in Spanish as a Foreign Language Using Oral Tradition Stories: The Witches of La Jagua and Colombia’s Linguistic and Cultural Diversity. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(8):949. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15080949

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuarín, Daniel. 2025. "A Methodological Route for Teaching Vocabulary in Spanish as a Foreign Language Using Oral Tradition Stories: The Witches of La Jagua and Colombia’s Linguistic and Cultural Diversity" Education Sciences 15, no. 8: 949. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15080949

APA StyleGuarín, D. (2025). A Methodological Route for Teaching Vocabulary in Spanish as a Foreign Language Using Oral Tradition Stories: The Witches of La Jagua and Colombia’s Linguistic and Cultural Diversity. Education Sciences, 15(8), 949. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15080949